Fanny Cole on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Fanny Buttery Cole ( Holder; 20 June 1860 – 25 May 1913) was a prominent

Fanny B. Holder worked as a teacher in Brookside and East Oxford public schools before she married in 1884 Herbert Cole of Kaiapoi (1858–1917). Herbert Cole was a

Fanny B. Holder worked as a teacher in Brookside and East Oxford public schools before she married in 1884 Herbert Cole of Kaiapoi (1858–1917). Herbert Cole was a  Her children were four and six years old in 1892, when Fanny Cole of

Her children were four and six years old in 1892, when Fanny Cole of

Since 1897, Fanny B. Cole was elected vice president of the Christchurch Union. The many activities undertaken by the Union that year included the establishment of coffee rooms to compete with alcohol-centric restaurants and hotels, a luncheon booth at the Agricultural & Pastoral Association Show that held hundreds of patrons, cottage meetings with Bible study in Linwood, registering factory girls to be able to vote, rescue work for young girls on the streets, and petitioning Parliament to reform the Juvenile Depravity Bill to include boys and not just girls. That year she and

Since 1897, Fanny B. Cole was elected vice president of the Christchurch Union. The many activities undertaken by the Union that year included the establishment of coffee rooms to compete with alcohol-centric restaurants and hotels, a luncheon booth at the Agricultural & Pastoral Association Show that held hundreds of patrons, cottage meetings with Bible study in Linwood, registering factory girls to be able to vote, rescue work for young girls on the streets, and petitioning Parliament to reform the Juvenile Depravity Bill to include boys and not just girls. That year she and

Christchurch International Exhibition

The goal was to show how various the work of the Unions, "under its all-embracing Do-Everything policy." Cole was invited to be on the platform at the opening ceremony, and she was sure that this was evidence of a "change in public sentiment with regard to Temperance. ... Assuredly the women of New Zealand banded together in the W.C.T.U. are now recognised as a force to be reckoned with in the political world." However, the part of the Exhibition that garnered space in th

Official Record

was "The Children's Rest," a building that accommodated a

Cole and

Cole and

Mohi Te Ātahīkoia

Mrs. Mohi (president of the local Union), Mrs. Tamehana, Mrs. Wharekape, Mr. Puhara, Hera Stirling Munro/Manaro, and Mrs. Kopua. The WCTU NZ response came from Mrs. H.E. Oldham of Napier (the business manager of ''The White Ribbon''), Vice President

temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

leader and women's rights advocate in New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. Cole was a founding member then president of the Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon River / ...

chapter of the Women's Christian Temperance Union New Zealand

Women's Christian Temperance Union of New Zealand (WCTU NZ) is a non-partisan, non-denominational, and non-profit organization that is the oldest continuously active national organisation of women in New Zealand. The national organization began ...

(WCTU NZ) and national WCTU NZ superintendent of the Press from 1897 through 1903. In 1906 Cole was elected national president of the WCTU NZ, a position she held until her untimely death shortly before her fifty-third birthday.

Early life

Fanny B. Holder was born at St. George's, Shropshire on 20 June 1860, the sixth of eight children of Fanny Buttery (1822–1883) and Charles Holder (1821–1895). Buttery was a surname ofHuguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

origin and pronounced ''Beautrais''. According to the England Census, Fanny and her siblings grew up in Wrockwardine Wood

Wrockwardine Wood (pronounced "Rock-war-dine") was originally a detached piece of woodland, then a township, formerly belonging to the manor and parish of Wrockwardine. Wrockwardine is located approximately 7 miles west from Wrockwardine Wood.

...

where her father worked as a bootmaker and served as the local Methodist preacher. Some of the family immigrated to New Zealand in 1880; and the four sisters lived near their parents in Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon River / ...

, marrying in quick succession as their mother grew ill and died. The eldest Sarah Elizabeth Holder (1854–1939) married in 1883 a Methodist minister, Rev. Daniel James Murray (1851–1928). Lydia Ann Holder (1856–1929) married a carpenter Andrew Harre (1859–1908) in 1884. Jane "Jennie" Holder (1864–1921) married in 1885 Thomas Oliver Johnson (1861–1932), a farmer.

Fanny B. Holder worked as a teacher in Brookside and East Oxford public schools before she married in 1884 Herbert Cole of Kaiapoi (1858–1917). Herbert Cole was a

Fanny B. Holder worked as a teacher in Brookside and East Oxford public schools before she married in 1884 Herbert Cole of Kaiapoi (1858–1917). Herbert Cole was a temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

worker for the "no-license" option and an agent for the Canterbury Farmers' Cooperative Association. On 1 October 1886, their elder daughter Marguerita Lilian "Daisy" Cole was born in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, on their estate called Ellengowan situated near the River Avon. The wetlands in the area were once called "Daisy Meadows."

Their second daughter, Eleanor Charlotte "Nellie" Cole (1888–1962) was also born there on 4 July 1888.

Her children were four and six years old in 1892, when Fanny Cole of

Her children were four and six years old in 1892, when Fanny Cole of Richmond, Christchurch

Richmond is a minor suburb of Christchurch, New Zealand.

Situated to the inner north east of the city centre, the suburb is bounded by Shirley Road to the north, Hills Road to the west, and the Avon River to the south and east.

In 2018, ongoin ...

signed the suffrage petition put forward by the Political Franchise Leagues and WCTU NZ. Cole had been part of the founding of the Christchurch Union when Mary C. Leavitt, the world organiser for the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

, visited in May 1885. There were forty-four founding members who they elected Emma E. Packe, president; Cecilia Wroughton, treasurer; and, Kate Sheppard

Katherine Wilson Sheppard ( Catherine Wilson Malcolm; 10 March 1848 – 13 July 1934) was the most prominent member of the women's suffrage movement in New Zealand and the country's most famous suffragist. Born in Liverpool, England, she emig ...

, secretary. Cole also signed the 1893 petition, the largest ever presented in the New Zealand Parliament, and which led to the successful acquisition of women's right to vote at the national level. They were still living at Ellangowan in Richmond according to the electoral rolls of 1896, but by 1894 Herbert Cole had started up a land agency business partnership with temperance activist Thomas "Tommy" E. Taylor. By 1900, according to the electoral roll of Lyttelton, the Cole family had moved to the Port Hills area overlooking the Lyttelton Harbour

Lyttelton Harbour / Whakaraupō is one of two major inlets in Banks Peninsula, on the coast of Canterbury, New Zealand; the other is Akaroa Harbour on the southern coast. It enters from the northern coast of the peninsula, heading in a pred ...

.

Temperance and women's rights leader

Since 1897, Fanny B. Cole was elected vice president of the Christchurch Union. The many activities undertaken by the Union that year included the establishment of coffee rooms to compete with alcohol-centric restaurants and hotels, a luncheon booth at the Agricultural & Pastoral Association Show that held hundreds of patrons, cottage meetings with Bible study in Linwood, registering factory girls to be able to vote, rescue work for young girls on the streets, and petitioning Parliament to reform the Juvenile Depravity Bill to include boys and not just girls. That year she and

Since 1897, Fanny B. Cole was elected vice president of the Christchurch Union. The many activities undertaken by the Union that year included the establishment of coffee rooms to compete with alcohol-centric restaurants and hotels, a luncheon booth at the Agricultural & Pastoral Association Show that held hundreds of patrons, cottage meetings with Bible study in Linwood, registering factory girls to be able to vote, rescue work for young girls on the streets, and petitioning Parliament to reform the Juvenile Depravity Bill to include boys and not just girls. That year she and Kate Sheppard

Katherine Wilson Sheppard ( Catherine Wilson Malcolm; 10 March 1848 – 13 July 1934) was the most prominent member of the women's suffrage movement in New Zealand and the country's most famous suffragist. Born in Liverpool, England, she emig ...

signed, as representatives of the Christchurch WCTU along with other Christchurch leaders such as Ada Wells

Ada Wells (née Pike, 29 April 1863 – 22 March 1933) was a feminist and social worker in New Zealand.

Biography

Ada Pike was born near Henley-on-Thames, South Oxfordshire, England. Her parents emigrated to New Zealand with their four gir ...

, a public letter to the Premier of New Zealand. They sought equal powers with male official visitors to gaols – to be granted powers of Justices of the Peace. "It is little use having women as official visitors to our jails, unless they have the same powers as men visitors."

That same year during the presidency of Annie Jane Schnackenberg

Annie Jane Schnackenberg ( Allen; 22 November 1835 – 2 May 1905) was a New Zealand Wesleyan missionary, temperance and welfare worker, and suffragist. She served as president of the Auckland branch of the Women's Christian Temperance Union N ...

of Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The List of New Zealand urban areas by population, most populous urban area in the country and the List of cities in Oceania by po ...

, Fanny B. Cole started working for the national WCTU NZ as superintendent for Press Work. By the next year, Cole was elected over incumbent Kate Sheppard

Katherine Wilson Sheppard ( Catherine Wilson Malcolm; 10 March 1848 – 13 July 1934) was the most prominent member of the women's suffrage movement in New Zealand and the country's most famous suffragist. Born in Liverpool, England, she emig ...

as president of the Christchurch Union, a position she held until her ascendancy to the national presidency of the WCTU NZ. She was hailed for her leadership skills which included "conciliatory, tactful methods of procedure," and that meetings "were specially noticeable for the absence of anything approaching friction."

WCTU NZ president, 1906–1913

1906 WCTU NZ convention

At the 1906 WCTU NZ convention conducted March 20–26 in Greymouth, hosted by the Anglican Church at Trinity Hall, Fanny B. Cole was elected national president. She was not present at this meeting – Mary Sadler Powell ofInvercargill

Invercargill ( , mi, Waihōpai is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. The city lies in the heart of the wide expanse of t ...

, Rachel Hull Don

Rachel Don ( Hull; 23 July 1866 – 4 September 1941) was an accredited Methodist local preacher who became a local and national leader in the Women's Christian Temperance Union New Zealand (WCTU NZ), serving as president from 1914 to 1926. Unde ...

of Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

, and Lily May Kirk Atkinson of Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

(the current president) removed their names from nomination in favor of the Christchurch Union's nomination of Cole – her candidacy was unanimously won. Cole formally accepted the role by letter.

Even before she was elected national president, Cole was working on representing all of the WCTU NZ at thChristchurch International Exhibition

The goal was to show how various the work of the Unions, "under its all-embracing Do-Everything policy." Cole was invited to be on the platform at the opening ceremony, and she was sure that this was evidence of a "change in public sentiment with regard to Temperance. ... Assuredly the women of New Zealand banded together in the W.C.T.U. are now recognised as a force to be reckoned with in the political world." However, the part of the Exhibition that garnered space in th

Official Record

was "The Children's Rest," a building that accommodated a

crèche

Crèche or creche (from Latin ''cripia'' "crib, cradle") may refer to:

*Child care center, an organization of adults who take care of children in place of their parents

*Nativity scene, a group of figures arranged to represent the birth of Jesus ...

for as many as sixty young children and babies per day. The Education Minister, Sir George Fowlds

Sir George Matthew Fowlds (15 September 1860 – 17 August 1934) was a New Zealand politician of the Liberal Party.

Biography Early life and career

Fowlds was born in Fenwick, East Ayrshire, Scotland. His father, Matthew Fowlds, was a handloo ...

wrote to her to thank the WCTU for their efforts at the Exhibition, especially in organising the Creche.

1907 national convention

The twenty-second Annual Convention was held inChristchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon River / ...

, February 14–20, 1907. Cole presided over the meetings and resulting resolutions showed her strong convictions – similar resolutions from the previous and following conventions under her leadership. The resolutions emphasized: anti war, anti-violence, remove disabilities hindering women from sitting as members of Parliament or other offices, protest against legalization of the Totalisator

A tote board (or totalisator/totalizator) is a numeric or alphanumeric display used to convey information, typically at a race track (to display the odds or payoffs for each horse) or at a telethon (to display the total amount donated to the chari ...

, creation of separate homes in rural areas with farms for men and women arrested due to a deficiency of sexual control; abolish the time limit of charges of criminal offences against girls; remove legal disabilities affecting illegitimate children; teach Scientific Temperance in schools; create economic equality of husband and wife – including restrictions on women's time and labour contained in Factory Acts; and, equal wages for equal work.

There were several hints in ''The White Ribbon'' about Cole's declining health from 1905 on. And, at the 1907 national convention in Christchurch and the celebrations at the International Exhibition, she excused herself after the formal business. "... the severe indisposition which seized her immediately after the garden party upset all her plans for the further entertainment of those delegates to the Convention." That year, too, her daughter Marguerite (''aka'' "Daisy") Lilian Cole became business manager of the ''White Ribbon'' – and began accompanying her mother to conventions.

1908 national convention

At the 1908 convention inAuckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The List of New Zealand urban areas by population, most populous urban area in the country and the List of cities in Oceania by po ...

, Cole could not speak for several moments after a particularly poignant presentation by two little girls dressed in temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

white. She said afterwards that she was overcome with grief, thinking of all the children at risk from the violence of drink and the liquor traffic. Hera Stirling, a former Salvation Army

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

officer and currently an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

missionary from Pūtiki, spoke eloquently about her work among the Māori in the Hawke's Bay, Waikato and Wanganui districts – and petitioned for the WCTU NZ to set aside funds specifically for Māori-related projects. The ''Auckland Star'' reporter noted in the summary of the meeting that the response to Stirling was positive (the delegates found her story "most distressing") though no action was taken. On Cole's way home to Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon River / ...

after the convention, she was interviewed by "Dominica" for a Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

newspaper about the WCTU's national efforts underway. Cole emphasized the campaign to abolish the Totalisator

A tote board (or totalisator/totalizator) is a numeric or alphanumeric display used to convey information, typically at a race track (to display the odds or payoffs for each horse) or at a telethon (to display the total amount donated to the chari ...

allowed in the Gambling Bill and that the Union chapters had gathered together 36,000 signatures to send as a petition to Parliament. She also spoke on the "legal disabilities of women and the economic independence of wives," e.g., the mother having no legal right to her child or say in keeping the home over her head. "... The Women's Union acts on the broad principle that it is woman's duty to oppose everything that is likely to injure the home or the interests of the home."

1909 national convention

The 1909 national WCTU NZ convention meetings were held in the Baptist church on Vivian Street inWellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

. It included two formal visits: one to the Hon. George Fowlds

Sir George Matthew Fowlds (15 September 1860 – 17 August 1934) was a New Zealand politician of the Liberal Party.

Biography Early life and career

Fowlds was born in Fenwick, East Ayrshire, Scotland. His father, Matthew Fowlds, was a handloo ...

Minister of Education on the successes of scientific temperance instruction, and one to the Premier Sir Joseph Ward

Sir Joseph George Ward, 1st Baronet, (26 April 1856 – 8 July 1930) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 17th prime minister of New Zealand from 1906 to 1912 and from 1928 to 1930. He was a dominant figure in the Liberal and Unit ...

to continue the fight against the Contagious Diseases Acts

The Contagious Diseases Acts (CD Acts) were originally passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1864 (27 & 28 Vict. c. 85), with alterations and additions made in 1866 (29 & 30 Vict. c. 35) and 1869 (32 & 33 Vict. c. 96). In 1862, a com ...

, inherited from the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

which promulgated men's use of prostitution and abused all women's rights when at any moment any woman could be accused of harboring a venereal disease. That year Cole and the WCTU NZ Canterbury District hosted a visit in Christchurch from the American WCTU missionary Katharine Lente Stevenson during their convention. Stevenson and Cole, both passionate advocates for scientific temperance and women's rights, quickly became good friends in that time which Stevenson called "our week of close comradeship." Cole attended the Australian Triennial Convention in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

that year in May to great acclaim by the Australian WCTU.

1910 national convention

Cole presided over the twenty-fifth national WCTU NZ convention atInvercargill

Invercargill ( , mi, Waihōpai is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. The city lies in the heart of the wide expanse of t ...

in February 1910. The presence of Hera Stirling "and other Maori Sisters at the Invercargill Convention and the part they played in the various gatherings, brought the native work prominently before the members of the Convention." This kicked off a formal effort at fundraising specifically for the support of Māori Unions with Mrs. E.H. Henderson serving both as WCTU NZ superintendent of Māori Work and of Māori Fundraising. At the 1910 convention, in addition to the usual resolutions for women's rights and economic justice, the delegates resolved that they would take advantage of new Municipal Act, which for the first time allowed both men and women ratepayers to nominate and vote for members to Hospital and Charitable Aid Boards. They also recommended that every Union form a "Y. Union, a Loyal Temperance Legion and a Cradle Roll" to reach out to youth and young mothers in a more sustainable way. That year the Contagious Diseases Acts

The Contagious Diseases Acts (CD Acts) were originally passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1864 (27 & 28 Vict. c. 85), with alterations and additions made in 1866 (29 & 30 Vict. c. 35) and 1869 (32 & 33 Vict. c. 96). In 1862, a com ...

were finally repealed by Parliament, and Cole credited the WCTU NZ with winning a fight against the "Social Evil" that had been going on since their very first national convention in 1886. The WCTU NZ leaders had "agitated for this repeal for many years and our members may cerainly claim that their strenuous efforts have been the means of keeping this matter before Parliament and the Cabinet Ministers, until justice has been done to the women of this Dominion."

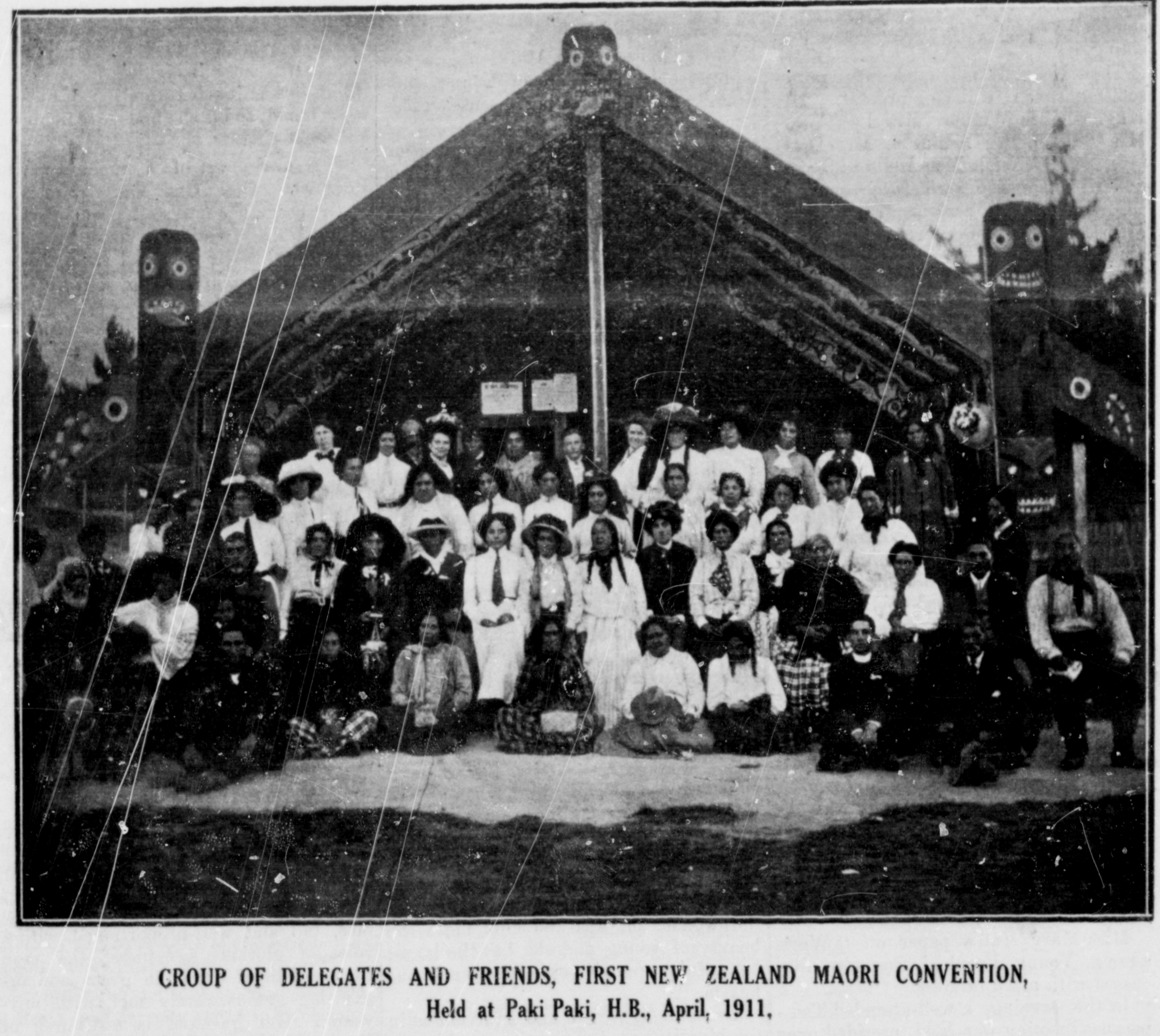

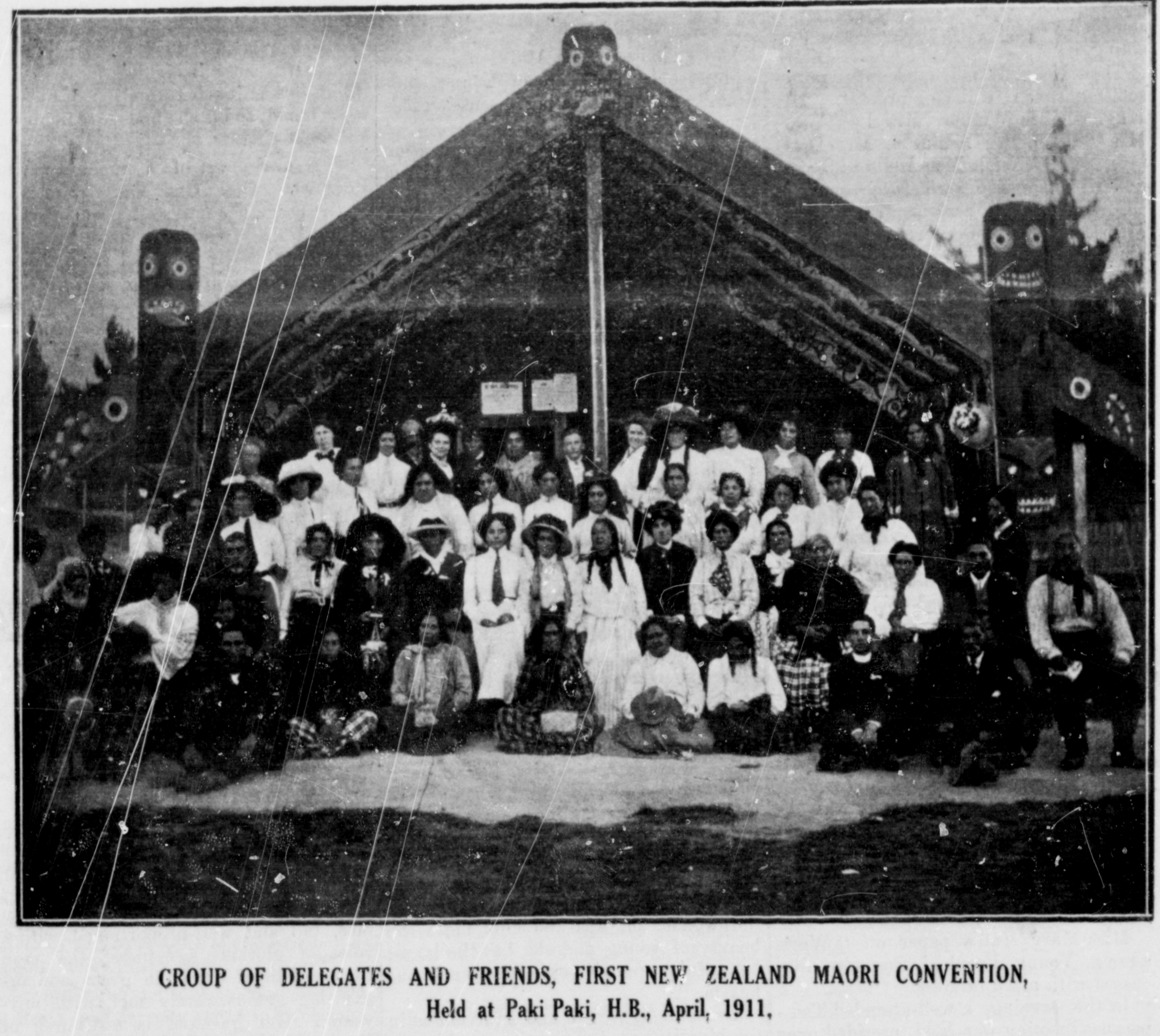

1911 national conventions – New Plymouth and Pakipaki

1911 started with Cole spending "some weeks in a private hospital" but announcing that she would still travel to the national convention in March atNew Plymouth

New Plymouth ( mi, Ngāmotu) is the major city of the Taranaki region on the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It is named after the English city of Plymouth, Devon from where the first English settlers to New Plymouth migrated. ...

and stand for re-election as president. ''The White Ribbon'' described the Convention of 1911 to have a record attendance of seventy-six delegates – and the national roster consisting of 2668 "paid up" members. Resolutions that year included a protest against Great Britain's opium traffic in China, and a vote of thanks to the New Zealand government for agreeing to post Temperance Wall Sheets in all public schools and to teach scientific temperance as a compulsory subject. Cole was re-elected president. Also at this convention, the delegates determined to hire another national organiser, in addition to the current organiser, Jean McNeish (later Gibbons). The new organiser would focus primarily on supporting and building out Māori Unions – an endeavor that had been underway for many years and recently boosted by Hera Stirling, an Anglican missionary before her marriage to Rev. Munro in 1910. A committee met to organise the work to be undertaken by the new Māori Organiser, Miss Rebecca Smith of Hokianga

The Hokianga is an area surrounding the Hokianga Harbour, also known as the Hokianga River, a long estuarine drowned valley on the west coast in the north of the North Island of New Zealand.

The original name, still used by local Māori, is ...

, in preparation for the convention in Pakipaki

Pakipaki is a pā kāinga ''village'' and rural community in the Hastings District and Hawke's Bay Region of New Zealand's North Island. The village is home to many Ngāti Whatuiāpiti hapū ''tribes'' represented by their three marae of Houngar ...

.

Cole and

Cole and Lily Atkinson

Lily May Atkinson (née Kirk, 29 March 1866 – 19 July 1921) was a New Zealand temperance campaigner, suffragist and feminist. She served in several leadership roles at the local and national levels including Vice President of the New Zealand ...

worked with Hera Stirling Munro of Rotorua

Rotorua () is a city in the Bay of Plenty region of New Zealand's North Island. The city lies on the southern shores of Lake Rotorua, from which it takes its name. It is the seat of the Rotorua Lakes District, a territorial authority encompass ...

, Jean McNeish of Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

and Rebecca Smith of Hokianga

The Hokianga is an area surrounding the Hokianga Harbour, also known as the Hokianga River, a long estuarine drowned valley on the west coast in the north of the North Island of New Zealand.

The original name, still used by local Māori, is ...

to organise the first WCTU NZ convention dedicated solely for Maori Unions. It was held at Pakipaki

Pakipaki is a pā kāinga ''village'' and rural community in the Hastings District and Hawke's Bay Region of New Zealand's North Island. The village is home to many Ngāti Whatuiāpiti hapū ''tribes'' represented by their three marae of Houngar ...

near Hastings, Hawke's Bay, April 10–14, 1911 – Cole and Atkinson planned to present at the convention together with leading Māori missionaries and temperance activists from all parts of the country. This area was a stronghold of the Māori Anglicans and cemented close ties between the Māori WCTU NZ leadership and the Young Māori Party

The Young Māori Party was a New Zealand organisation dedicated to improving the position of Māori. It grew out of the Te Aute Students Association, established by former students of Te Aute College in 1897. It was established as the Young Māori ...

. Sixty-five delegates representing seven WCTU NZ Unions conducted the business meetings, and hundreds of visitors attended the public meetings and feasts. Though she had promised Hera Stirling Munro the year before that she would attend, Cole wrote a letter that was read at the convention that she had been "very near the gates of death," and so she was still not strong enough since the Invercargill

Invercargill ( , mi, Waihōpai is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. The city lies in the heart of the wide expanse of t ...

convention to travel again so soon after her trip to New Plymouth

New Plymouth ( mi, Ngāmotu) is the major city of the Taranaki region on the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It is named after the English city of Plymouth, Devon from where the first English settlers to New Plymouth migrated. ...

. The opening ceremony, after a church service in the Paki Paki Hall led by Archdeacon David Ruddock, included speeches bMohi Te Ātahīkoia

Mrs. Mohi (president of the local Union), Mrs. Tamehana, Mrs. Wharekape, Mr. Puhara, Hera Stirling Munro/Manaro, and Mrs. Kopua. The WCTU NZ response came from Mrs. H.E. Oldham of Napier (the business manager of ''The White Ribbon''), Vice President

Lily Atkinson

Lily May Atkinson (née Kirk, 29 March 1866 – 19 July 1921) was a New Zealand temperance campaigner, suffragist and feminist. She served in several leadership roles at the local and national levels including Vice President of the New Zealand ...

, and World WCTU missionary Bessie Harrison Lee Cowie. The delegates decided to create a Māori District Union within the WCTU NZ with Hera Stirling Munro/Manaro elected President and Matehaere Arapata Tiria "Ripeka" Brown Halbert as Vice President. The convention was a high point in the decade-long process of inclusion of Māori in the WCTU NZ. A report early the next year by Mrs. E.H. Henderson of Waikato

Waikato () is a Regions of New Zealand, local government region of the upper North Island of New Zealand. It covers the Waikato District, Waipa District, Matamata-Piako District, South Waikato District and Hamilton, New Zealand, Hamilton City ...

, WCTU NZ superintendent and treasurer for Māori Work, showed that 44 Unions had been formed with a membership of some 600 men and women.

1912 national convention

Cole's steadying hand was seen with the WCTU NZ reaction to the large vote polled for National Prohibition – 56% for it, though not enough to win the day since a 3/5 majority was needed for it to carry. The twenty-seventh annual convention held atDunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

March 14–21 opened with 75 delegates present for a lecture on the increasingly popular topic of Eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

and a speech on the values of moderation by the President of the Dunedin Reform Council. Cole responded carefully in opposition with a demeanor considered "gracious, sweet, and womanly," by saying "We mothers are not here to protect monopolies, but men." Cole's presidential address included a controversial stance against moderation in her plea for empathy with the suffragettes

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

in England, insisting that:

:Force was first used by the men who opposed the suffrage, and force has been met by force in this case. ... We are not defending such extreme measures, but those agitators won their point after a display of force terrible in its effects. Many contend that the women of Great Britain are injuring their cause by a display of force mild in its effects compared with that used by men in days gone by, who won for their class a right to a share in the Government of the country. The fact is clear that the militant suffragists have made their cause what it never was before, a power to be reckoned with. They are citizens, and as citizens who are denied justice, they are battling for what they value far more than comfort, ease, luxury, or the approval of their friends. Fines, imprisonment, injury to health and limb, even death itself, have been borne by women in this great cause for justice and right. Let us never utter a disparaging word of them or their methods. We, who won the franchise by peaceful tactics, because our public men were just and chivalrous, have no right to question the methods of these sisters, who are fighting with the backs to the wall for a share in the Government of the country, as a means of improving the condition of life for those who sit in darkness, and in the show of death, their sisters and ours.

Cole also supported the convention's resolution protesting the recent Defence Act by stating:

:"the military authorities have placed in their hands so much power, that we are in danger of liberty of conscience, and liberty of thought, becoming things of the past in a country where the inhabitants are supposed to be the freest on the face of the earth." She wrote to Sir Robert S. Baden-Powell, founder of the world-wide Scout Movement, to get his support for allowing boys under 18 in New Zealand to substitute participation in the Scouts for the Cadet system.

Cole played a large role in the Canterbury Provincial Convention of 1912 held at Kaiapoi

Kaiapoi is a town in the Waimakariri District of the Canterbury region, in the South Island of New Zealand. The town is located approximately 17 kilometres north of central Christchurch, close to the mouth of the Waimakariri River. It is con ...

in which she pushed for resolutions against the "so-called Sports Protection League" which was in favor of mechanising the totalisator

A tote board (or totalisator/totalizator) is a numeric or alphanumeric display used to convey information, typically at a race track (to display the odds or payoffs for each horse) or at a telethon (to display the total amount donated to the chari ...

, a large display board for betting

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of value ("the stakes") on a random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy are discounted. Gambling thus requires three elem ...

at horse tracks. Cole was elected the District president.

1913 national convention

The sixty-four delegates who attended the national convention atNelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

March 5–13, 1913, noticed that Cole "looked somewhat frail after her recent illness." They gave her a "great ovation" when she rose to speak about the important legacy of Nelson's women's rights advocate Mary Ann Wilson Griffiths Müller and Total Abstinence leader Alfred Saunders

Alfred Saunders (12 June 1820 – 28 October 1905) was a 19th-century New Zealand politician.

Early life

Saunders was born in 1820 in Market Lavington, the youngest son of Mary and Amram Saunders. He was educated in Market Lavington and at a B ...

. Her presidential address was a passionate statement for women's rights in many different arenas. She particularly focused on the debates over national prohibition, and she hoped that those opposed to prohibition would "consider the rights of the wives, mothers, and children of their deluded victims, who have been robbed of the comfort of home, food, and clothing in order to keep the publicans' coffers full ... Artificial protection for a trade that is the most prolific source of crime, vice, and misery is subversive of all that is just and right." Cole was re-elected as president. Cole's last official act was drawing up and signing a circular letter as issued by direction of the Convention that the WCTU NZ disapproved of the platform of the Bible in Schools League and for the various church leaders to stop fighting over this issue.

Death and legacy

On 25 May 1913, at her home at Cashmere Hills, Fanny Cole died – only fifty-two years old. Her burial procession on 28 May included the Christchurch Mayor and City Council among the large attendance. Rev. Leonard Isitt, by then a Member of Parliament, spoke about Cole's commitment to temperance and beyond that to all forms of social and economic justice for all women and children. A memorial service was held on June 1 at theSydenham Sydenham may refer to:

Places Australia

* Sydenham, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney

** Sydenham railway station, Sydney

* Sydenham, Victoria, a suburb of Melbourne

** Sydenham railway line, the name of the Sunbury railway line, Melbourne ...

Methodist Church, of which she had been a member.

Delegates of the Canterbury Provincial Convention in October 1913 voted to call for funds to create a national memorial to Fanny Cole. The most they ended up doing was to create a memorial stone at her grave in Linwood Cemetery, Christchurch

Linwood Cemetery is a cemetery located in Linwood, Christchurch, New Zealand. It is the fifth oldest public cemetery in the city. Despite its age, it is still open for ashes interment, Hebrew Congregational burials and if there is space in existi ...

– the stone was unveiled and dedicated with a large procession during the 1915 convention in 1915.

In addition, the Christchurch WCTU NZ donated £150 in Cole's honour to be invested, with the interest used to provide prizes for the Temperance Examinations. The prizes were known as the Fanny Cole Memorial Prize.

After Fanny Cole's death, Herbert Cole married his second wife in 1915: Amy Jane Alley, a teacher in the North Canterbury District. The Cole daughters married after both their parents' deaths, but neither had children of their own. Nellie, the younger daughter at 33 years of age, married Henry McMaster in 1921 (then after his death, she married Charles James Hawker in 1944); and, Daisy at 36 years of age married Archibald "Archie" James Hodges in 1922. Their step-mother, Amy Jane Cole (1868–1944) remarried in 1926 to Edward Thomas Mulcock.

See also

*Alcohol in New Zealand

Alcohol has been consumed in New Zealand since the arrival of Europeans. The most popular alcoholic beverage is beer. The legal age to purchase alcohol is 18.

History Early history

There is no oral tradition or archaeological evidence of Māor ...

*List of New Zealand suffragists

This is a List of New Zealand suffragists who were born in New Zealand or whose lives and works are closely associated with that country.

A

* Georgina Shorland Abernethy (1859–1906), president of the Gore Women's Franchise League

* Lily May ...

*Temperance movement in New Zealand

The temperance movement in New Zealand originated as a social movement in the late-19th century. In general, the temperance movement aims at curbing the consumption of alcohol. Although it met with local success, it narrowly failed to impose nat ...

*Women's Christian Temperance Union New Zealand

Women's Christian Temperance Union of New Zealand (WCTU NZ) is a non-partisan, non-denominational, and non-profit organization that is the oldest continuously active national organisation of women in New Zealand. The national organization began ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cole, Fanny 1860 births 1913 deaths English emigrants to New Zealand New Zealand educators New Zealand temperance activists People from Christchurch New Zealand feminists New Zealand suffragists 19th-century New Zealand people Woman's Christian Temperance Union people 20th-century New Zealand people 20th-century New Zealand women 19th-century New Zealand women Burials at Linwood Cemetery, Christchurch