Fallen Timbers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

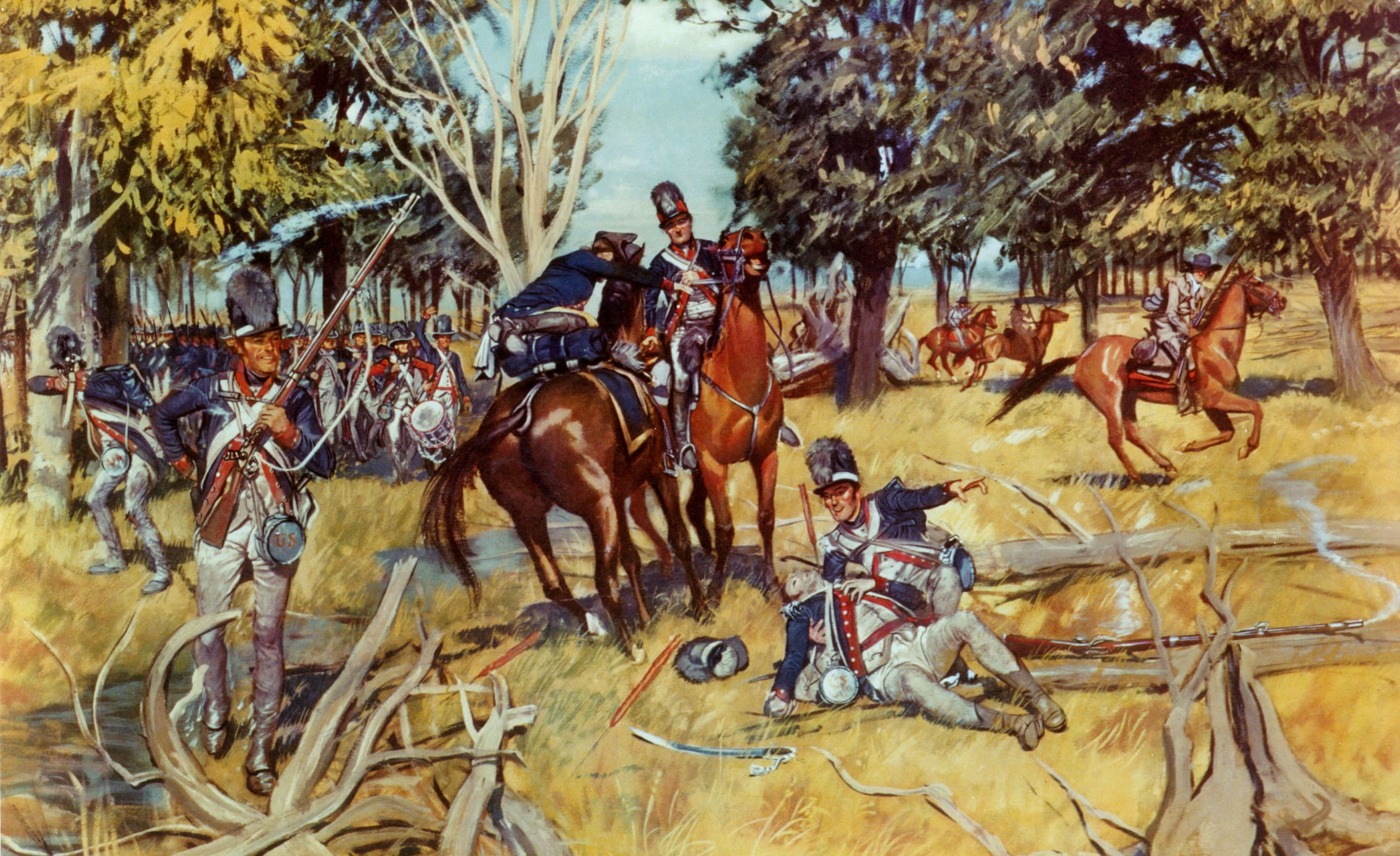

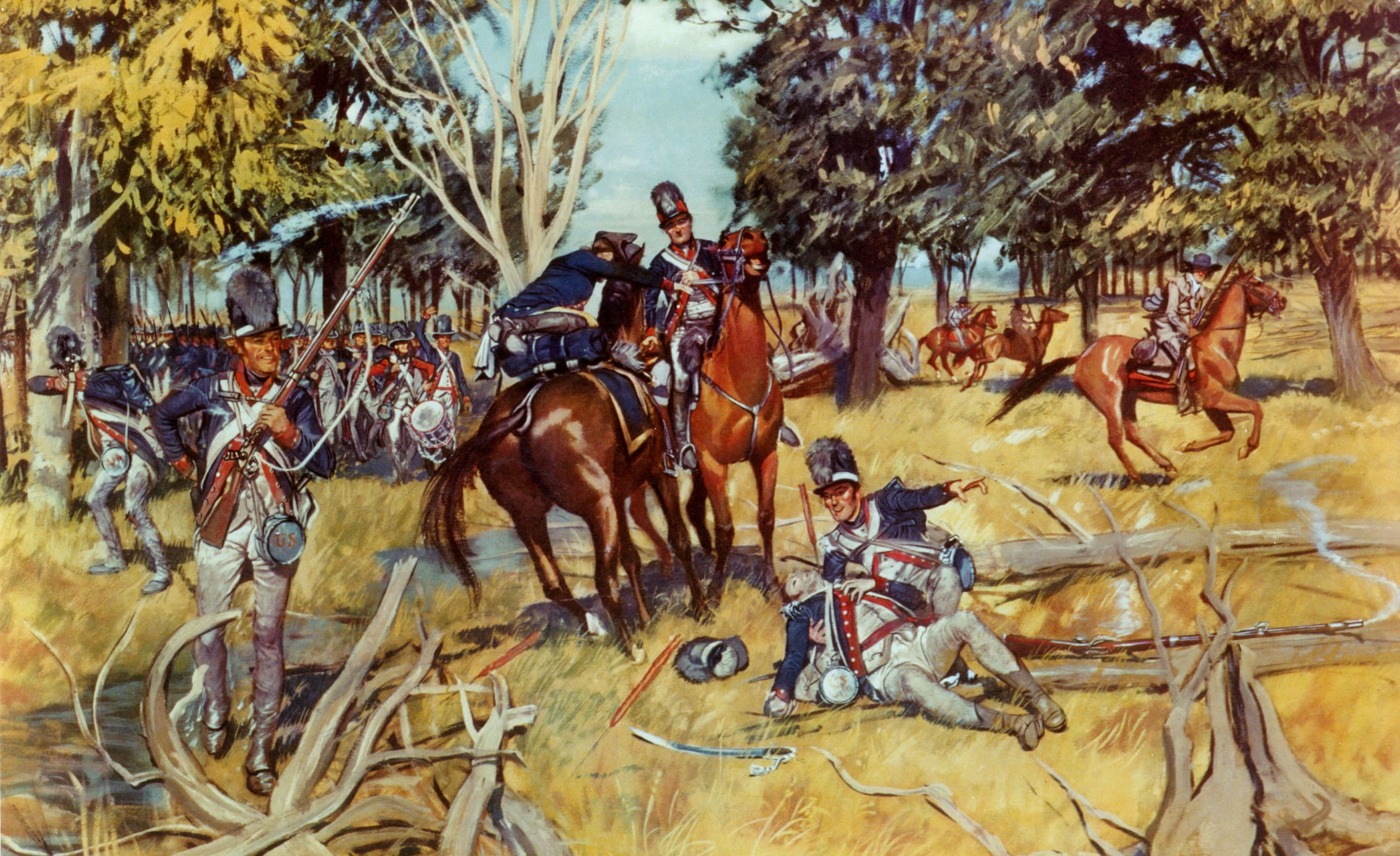

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the

Wayne's army encamped for three days in sight of Fort Miami, which was commanded by British Major William Campbell. When Major Campbell asked the meaning of the encampment, Wayne replied that the answer had already been given by the sound of their muskets and the retreat of the Indians. General Wayne had already determined that he could not take Fort Miami by force, because his

Wayne's army encamped for three days in sight of Fort Miami, which was commanded by British Major William Campbell. When Major Campbell asked the meaning of the encampment, Wayne replied that the answer had already been given by the sound of their muskets and the retreat of the Indians. General Wayne had already determined that he could not take Fort Miami by force, because his

On 14 September 1929, the

On 14 September 1929, the

The

The

Battle of Fallen Timbers

– Chickasaw.TV

Battle of Fallen Timbers Battle of Fallen Timbers

–

Fallen Timbers Battlefield and Fort Miamis National Historic Site

from

The Fallen Timbers battlefield todayMaumee Valley Heritage CorridorOhio History Central

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110421223417/http://fallentimbersbattlefield.com/ Battle of Fallen Timbers – The Toledo Metroparks* {{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Fallen Timbers 1794 in the United States

Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1786–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern ...

, a struggle between Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy

The Northwestern Confederacy, or Northwestern Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States created after the American Revolutionary War. Formally, the confederacy referred to it ...

and their British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

allies, against the nascent United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

for control of the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. The battle took place amid trees toppled by a tornado near the Maumee River

The Maumee River (pronounced ) ( sjw, Hotaawathiipi; mia, Taawaawa siipiiwi) is a river running in the United States Midwest from northeastern Indiana into northwestern Ohio and Lake Erie. It is formed at the confluence of the St. Joseph and ...

in northwestern Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

at the site of the present-day city of Maumee, Ohio

Maumee ( ) is a city in Lucas County, Ohio, United States. Located along the Maumee River, it is about 10 miles southwest of Toledo. The population was 14,286 at the 2010 census. Maumee was declared an All-America City by the National Civic L ...

.

Major General "Mad Anthony" Wayne's Legion of the United States

The Legion of the United States was a reorganization and extension of the Continental Army from 1792 to 1796 under the command of Major General Anthony Wayne. It represented a political shift in the new United States, which had recently adopte ...

, supported by General Charles Scott's Kentucky Militia, were victorious against a combined Native American force of Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

under Blue Jacket

Blue Jacket, or Weyapiersenwah (c. 1743 – 1810), was a war chief of the Shawnee people, known for his militant defense of Shawnee lands in the Ohio Country. Perhaps the preeminent American Indian leader in the Northwest Indian War, i ...

, Ottawas under Egushawa Egushawa (c. 1726 – March 1796), also spelled Egouch-e-ouay, Agushaway, Agashawa, Gushgushagwa, Negushwa, and many other variants, was a war chief and principal political chief of the Ottawa tribe of North American Indians. His name is loosely ...

, and many others. The battle was brief, lasting little more than one hour, but it scattered the confederated Native forces. The U.S. victory ended major hostilities in the region. The following Treaty of Greenville

The Treaty of Greenville, formally titled Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., was a 1795 treaty between the United States and indigenous nations of the Northwest Territory (now Midwestern United States), including the Wyandot and Delaware peoples, ...

and Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

forced Native American displacement from most of modern-day Ohio, opening it to White American

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

settlement, along with withdrawal of the British presence from the southern Great Lakes region

The Great Lakes region of North America is a binational Canadian–American region that includes portions of the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin along with the Canadian p ...

of the United States.

Prelude

In the 1783Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

, which ended the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

ceded rights to the region northwest of the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

and south of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

. Despite the treaty, which ceded the Northwest Territory to the United States, the British maintained a military presence in their forts there and continued policies that supported the Native Americans to slow American expansion. With the encroachment of European-American settlers west of the Appalachians after the War, a Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

-led confederacy formed in 1785 to resist the usurpation of Indian lands, declaring that lands north and west of the Ohio River were Indian territory. The young United States formally organized the region in the Land Ordinance of 1785 The Land Ordinance of 1785 was adopted by the United States Congress of the Confederation on May 20, 1785. It set up a standardized system whereby settlers could purchase title to farmland in the undeveloped west. Congress at the time did not have ...

and negotiated treaties allowing settlement, but the Western Confederacy

The Northwestern Confederacy, or Northwestern Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States created after the American Revolutionary War. Formally, the confederacy referred to it ...

of Native American nations were not party to these treaties and refused to acknowledge them. Violence erupted in the area between Native Americans and U.S. settlers in the region and in Kentucky. In George Washington's first term as President of the United States, the U.S. launched two major campaigns to subdue the British supported confederacy and protect borders from the British. The Harmar campaign in 1790 resulted in a significant victory for the confederacy and a U.S. retreat to Fort Washington. In May 1791, Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson

James Wilkinson (March 24, 1757 – December 28, 1825) was an American soldier, politician, and double agent who was associated with several scandals and controversies.

He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, b ...

's launched what he thought was a clever raid at the Battle of Kenapacomaqua

The Battle of Kenapacomaqua, also called the Battle of Old Town, was a raid in 1791 by United States forces under the command of Lieutenant Colonel (later Brigadier General) James Wilkinson on the Miami ( Wea) town of Kenapacomaqua on the Eel R ...

, Wilkinson killed 9 Wea and Miami, and captured 34 Miami as prisoners, including a daughter of Miami war chief Little Turtle

Little Turtle ( mia, Mihšihkinaahkwa) (1747 July 14, 1812) was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader ...

. Many of the confederation leaders were considering terms of peace to present to the United States, but when they received news of Wilkinson's raid, they readied for war. Wilkinson's raid thus had the opposite effect, uniting the tribes against St. Clair. In 1791, a follow-up campaign was led by territorial governor Arthur St. Clair

Arthur St. Clair ( – August 31, 1818) was a Scottish-American soldier and politician. Born in Thurso, Scotland, he served in the British Army during the French and Indian War before settling in Pennsylvania, where he held local office. During ...

, which was decimated by combined confederate forces.

Following this devastating defeat, the area was now open to attacks from the British and or their allied native tribes in the west. The U.S. quickly appointed envoys to negotiate peace with the confederacy. Meanwhile, President Washington commissioned Major General "Mad" Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

to recruit, and train a more effective, and larger force. If peace negotiations failed, Wayne was to bring U.S. sovereignty to the new borders. Wayne commanded about 2,000 men, with Joseph Bartholomew, Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

and Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as ...

men serving as his scouts. In the spring of 1793, Wayne moved the Legion from Pennsylvania downriver to Fort Washington, at a camp Wayne named Hobson's Choice

A Hobson's choice is a free choice in which only one thing is actually offered. The term is often used to describe an illusion that multiple choices are available. The most well known Hobson's choice is "I'll give you a choice: take it or leave ...

because they had no other options.

When Wayne received news that a grand council of the confederacy had not reached a peace agreement with U.S. negotiators, he moved his army north into Indian held territory. In November, the Legion built a new fort north of Fort Jefferson, which Wayne named Fort Greeneville. The Legion wintered here, but Wayne dispatched a detachment of about 300 men on 23 December to quickly build Fort Recovery

Fort Recovery was a United States Army fort ordered built by General "Mad" Anthony Wayne during what is now termed the Northwest Indian War. Constructed from late 1793 and completed in March 1794, the fort was built along the Wabash River, with ...

on the site of St. Clair's defeat and recover the cannons lost there in 1791. In response, the British built Fort Miami to block Wayne's advance and to protect Fort Lernoult

Fort Shelby was a military fort in Detroit, Michigan that played a significant role in the War of 1812. It was built by the United Kingdom, British in 1779 as Fort Lernoult, and was ceded to the United States by the Jay Treaty in 1796. It was rena ...

in Detroit. In January 1794, Wayne reported to Knox that 8 companies and a detachment of artillery under Major Henry Burbeck had claimed St. Clair's battleground and had already built a small fort. By June, Fort Recovery had been reinforced, and the Legion had recovered four copper cannons (two six-pound and two three-pound), two copper howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s, and one iron carronade

A carronade is a short, smoothbore, cast-iron cannon which was used by the Royal Navy. It was first produced by the Carron Company, an ironworks in Falkirk, Scotland, and was used from the mid-18th century to the mid-19th century. Its main func ...

. The fort was attacked that month, and although the Legion suffered heavy casualties, they maintained control of the fort, and the battle exposed divisions within the confederacy.

Before departing Fort Recovery, Wayne sent a final offer of peace with two captured prisoners to the leaders of the confederation at Roche de Bout. The confederacy leaders debated among themselves. Little Turtle

Little Turtle ( mia, Mihšihkinaahkwa) (1747 July 14, 1812) was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader ...

declared Wayne as a "the Chief who never sleeps," and recommended that the confederation should negotiate peace with Wayne. Blue Jacket mocked Little Turtle as a traitor and convinced the others that Wayne would be defeated, just as Harmar and St. Clair had been. Little Turtle then relinquished leadership to Blue Jacket, stating that he would only be a follower. The perceived cracks in the united confederacy concerned the British, who sent reinforcements to Fort Miami on the Maumee River.

Wayne departed Fort Recovery on 17 August and pushed north, buttressed by about 1,000 mounted Kentucky militia under General Charles Scott. Native American scouts noted that the Legion only marched until early afternoon, then stopped to build a fortified encampment, making attack on camps less practical than in previous US campaigns. The Legion constructed Fort Adams

Fort Adams is a former United States Army post in Newport, Rhode Island that was established on July 4, 1799 as a First System coastal fortification, named for President John Adams who was in office at the time. Its first commander was Capt ...

and Fort Defiance, so named from a declaration by Charles Scott that "I defy the English, Indians, and all the devils of hell to take it." Finally, as the Legion approached Fort Miami, Wayne stopped to build Fort Deposit as a baggage camp so that the Legion could go into battle as light infantry

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often fought ...

.

Battle

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

William Wells, Little Turtle's son-in-law and the commander of Wayne's intelligence company, was wounded along with some of his spies after they were identified spying in a Native American camp the night of 11 August. The Choctaw and Chickasaw scouts left the Legion at Fort Defiance after seeing how sick Wayne had become on the campaign. Wayne therefore ordered Captain George Shrim, commander of the Legion's ranger detachment, to lead a party of mounted scouts. On 18 August, Native American forces captured one of the scouts, William May, from whom they learned that Wayne intended to attack on the 19th, unless he stopped to build a supply depot, in which case he would attack on the 20th. Alexander McKee urged the confederacy to choose a suitable battlefield, since they knew the date of the attack. Suspecting that Wayne would march along the Maumee River

The Maumee River (pronounced ) ( sjw, Hotaawathiipi; mia, Taawaawa siipiiwi) is a river running in the United States Midwest from northeastern Indiana into northwestern Ohio and Lake Erie. It is formed at the confluence of the St. Joseph and ...

, Blue Jacket took a defensive position not far from present-day Toledo, Ohio

Toledo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Lucas County, Ohio, United States. A major Midwestern United States port city, Toledo is the fourth-most populous city in the state of Ohio, after Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, and according ...

, where a stand of trees (the "fallen timbers") had been blown down by a storm. The tangled debris stretched for nearly a mile, and the heavy brush created a natural abatis

An abatis, abattis, or abbattis is a field fortification consisting of an obstacle formed (in the modern era) of the branches of trees laid in a row, with the sharpened tops directed outwards, towards the enemy. The trees are usually interlaced ...

which would protect the confederate warriors. The Native American forces, numbering about 1,500, comprised Blue Jacket's Shawnees, Delawares led by Buckongahelas

Buckongahelas (c. 1720 – May 1805) together with Little Turtle & Blue Jacket, achieved the greatest victory won by Native Americans, killing 600. He was a regionally and nationally renowned Lenape chief, councilor and warrior. He was ac ...

, Miamis

The Miami ( Miami-Illinois: ''Myaamiaki'') are a Native American nation originally speaking one of the Algonquian languages. Among the peoples known as the Great Lakes tribes, they occupied territory that is now identified as North-central Indi ...

led by Little Turtle

Little Turtle ( mia, Mihšihkinaahkwa) (1747 July 14, 1812) was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader ...

, Wyandot

Wyandot may refer to:

Native American ethnography

* Wyandot people, also known as the Huron

* Wyandot language

* Wyandot religion

Places

* Wyandot, Ohio, an unincorporated community

* Wyandot County, Ohio

* Camp Wyandot, a Camp Fire Boys and ...

s led by Tarhe

Tarhe (1742–1818) was a leader of the Wyandot people in the Ohio Country. His nickname was "The Crane". He fought American expansion into the region until the Northwestern Confederacy was defeated at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. After ...

and Roundhead

Roundheads were the supporters of the Parliament of England during the English Civil War (1642–1651). Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I of England and his supporters, known as the Cavaliers or Royalists, who ...

, Ojibwa

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

s, Odawa

The Odawa (also Ottawa or Odaawaa ), said to mean "traders", are an Indigenous American ethnic group who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, commonly known as the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. They ha ...

led by Egushawa Egushawa (c. 1726 – March 1796), also spelled Egouch-e-ouay, Agushaway, Agashawa, Gushgushagwa, Negushwa, and many other variants, was a war chief and principal political chief of the Ottawa tribe of North American Indians. His name is loosely ...

, Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

led by Little Otter, Mingo

The Mingo people are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans, primarily Seneca and Cayuga, who migrated west from New York to the Ohio Country in the mid-18th century, and their descendants. Some Susquehannock survivors also joined them, and ...

s, a small detachment of Mohawks

The Mohawk people ( moh, Kanienʼkehá꞉ka) are the most easterly section of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy. They are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous people of North America ...

, and a British company of Canadian militiamen dressed as Native Americans under Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

William Caldwell. After taking their positions starting on 17–18 August, the Native forces fasted in preparation for battle.

Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Wilkinson urged Wayne to attack with haste before the native forces could assemble, but Wayne opted to fortify Fort Deposit. On the 19th, Wayne sent a battalion of mounted scouts under Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

William Price to reconnoiter the area. They encountered a number of confederate positions, but no shots were fired. At the end of that day, a confederate council was held, and it was determined that as Wayne might prepare for battle for several days, their warriors would be given permission to eat the next morning.

The Legion advanced early the next morning, 20 August, while the Native Americans were on their 3rd day of fasting. Due to morning rains, many warriors in the confederacy assumed there would be no battle, and retired to Fort Miami to break their fast. Suspecting contact, Wayne ordered the Legion to march in compacted columns, and distributed the dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

s and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

in the center of the column so that they could respond to an attack from any direction. A battalion of mounted Kentucky militia led the column, and had difficulty with the terrain. The lead scouts were only about 100 yards into the center of the chosen battlefield when the Odawas and Potawatomis under Little Otter and Egushawa Egushawa (c. 1726 – March 1796), also spelled Egouch-e-ouay, Agushaway, Agashawa, Gushgushagwa, Negushwa, and many other variants, was a war chief and principal political chief of the Ottawa tribe of North American Indians. His name is loosely ...

fired their first volley, scattering the militia. Behind the militia were two companies of infantry from the 4th Sub-Legion under Captain John Cook, and he directed their initial volley at the Kentuckians, whom he considered to be fleeing the battle. Soon, however, Cook's detachment fled the scene as advancing warriors initiated hand-to-hand fighting.

The fleeing U.S. forces ran towards the left wing of the Legion's column, where Lieutenant Colonel Jean François Hamtramck

Jean-François Hamtramck (sometimes called John Francis Hamtramck) (1756–1803) was a Canadian who served as an officer in the US Army during the American Revolutionary War and the Northwest Indian War. In the Revolution, he participated in the ...

commanded the 2nd and 4th sub-legions. They broke through Captain Howell Lewis' company, which fell back without firing a shot. Hamtramck, meanwhile, formed his wing into two ranks to halt the pursuing warriors, many of whom were armed with only tomahawks and knives, and General Wilkinson formed the 1st and 3rd sub-legions into one extended line covering 800 yards of the right wing. Wayne rushed to the sound of the muskets, and quickly deployed two light infantry companies from the center ahead of each wing, to halt any confederate advances until the lines could be properly formed. Artillery was brought to the front and blasted the Native American line with grapeshot. Blue Jacket's well-organized ambush was now in disarray, as the center elements had rushed forward while the wings had remained in position. When asked for orders by his aide-de-camp, Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, Wayne responded " Charge the damned rascals with the bayonet!"

Captain Robert Campbell charged first, leading his company of dragoons across 60–100 yards with sabres drawn. Nearly a dozen of the dragoons were shot in the attack, and Captain Campbell was killed. Wilkinson's dismounted infantry made a slow advance to support the dragoons, and the Odawas and Potawatomis ran back to their positions. The pursuit was so lightly challenged that Wilkinson feared they were being led into a trap, and he paused to await instructions from Wayne.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Hamtramck advanced at trail arms and encountered the Wyandots

The Wyandot people, or Wyandotte and Waⁿdát, are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. The Wyandot are Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples of North America who emerged as a confeder ...

, Lenape, and Canadians. A heavy exchange of fire ensued, and the confederate forces attempted to flank the 4th sub-legion. Instead, a brigade of Kentucky militia under Brigadier General Robert Todd moved quickly through the swamp and flanked the Canadians. The 4th sub-legion pursued with fixed bayonets. The confederated forces retreated from their original positions, and were unable to effectively re-form in the rough terrain.

Wilkinson eventually resumed a cautious advance along the ridge high above the Maumee River. On route to Fort Miami, the Native forces had to cross a ravine. The Odawa and Potawatomi attempted to regroup here. Egushawa was in command, but was wounded when he was shot through the eye. Little Otter was severely wounded, and was thrown on the back of a white horse and evacuated so he could not be captured by the Legion. Another Odawa chief, Turkey Foot, stood atop a large rock and urged the warriors to make their stand, but he was shot in the chest and died almost instantly. According to Alexander McKee, the loss of so many confederate leaders made the Native American losses seem greater than they actually were, and many warriors fled to Fort Miami.

Beyond the ravine, the landscape was much more open, allowing the Legion to advance more quickly and giving dragoons a frightening advantage over dismounted warriors. McKee, Matthew Elliot, and Simon Girty tried to rally the retreating forces one last time, but they were largely ignored. The retreat became a disorganized rout, except for the rear guard protection provided by the Canadians and Wyandots.

The entire battle lasted an hour and ten minutes. The Indian warriors fled towards Fort Miami but were surprised to find the gates closed against them. Major William Campbell, the British commander of the fort, had closed the gates when the first warriors arrived and the sounds of musket fire came closer. He refused to open the gates now and give refuge to the confederate warriors, unwilling to start a war with the United States. The remnants of the confederate army continued north and reunited near Swan Creek, where their families were encamped. McKee tried to rally them once more, but they refused to fight again, especially after the betrayal of the British at Fort Miami.

Wayne's army had lost 33 men and had about 100 wounded. They reported that they had found 30–40 dead warriors. Alexander McKee

Alexander McKee ( – 15 January 1799) was an American-born military officer and colonial official in the British Indian Department during the French and Indian War, the American Revolutionary War, and the Northwest Indian War. He achieved the ...

of the British Indian Department

The Indian Department was established in 1755 to oversee relations between the British Empire and the First Nations of North America. The imperial government ceded control of the Indian Department to the Province of Canada in 1860, thus setting ...

reported that the Indian confederacy lost 19 warriors killed, including Chief Turkey Foot of the Ottawa. Six white men fighting on the Native American side were also killed, and Chiefs Egushawa and Little Otter of the Ottawa were wounded.

Post-hoc

Wayne's army encamped for three days in sight of Fort Miami, which was commanded by British Major William Campbell. When Major Campbell asked the meaning of the encampment, Wayne replied that the answer had already been given by the sound of their muskets and the retreat of the Indians. General Wayne had already determined that he could not take Fort Miami by force, because his

Wayne's army encamped for three days in sight of Fort Miami, which was commanded by British Major William Campbell. When Major Campbell asked the meaning of the encampment, Wayne replied that the answer had already been given by the sound of their muskets and the retreat of the Indians. General Wayne had already determined that he could not take Fort Miami by force, because his howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s were underpowered and he did not have enough provisions for an extended siege. Instead, to illustrate that the U.S. controlled the region, he rode alone to the walls of Fort Miami and slowly conducted an inspection of the fort's exterior. The British garrison debated whether or not to engage the General, but in the absence of orders and being already at war with France, Major Campbell declined to fire the first shot at the United States. The Legion, meanwhile, destroyed Indian villages and crops in the region of Fort Deposit, and burned Alexander McKee's trading post within sight of Fort Miami. Despite the provocations, the British would not open the gates to the fort. General Wayne was as unwilling to start a war with Great Britain as Major Campbell was to start a war with the United States, and so finally, on 26 August, the Legion departed for Fort Recovery

Wayne expected a new attack, and even hoped for it while the Legion was at full strength. Although the Native Americans did not reform into a large army, small bands continued to harass the Legion's perimeter, scouts, and supply trains. Although they resented the assignment, Wayne assigned the mounted militia to carry supplies between the chain of forts. On 12 September, Wayne issued invitations for peace negotiations, but they went unanswered. Finally, on 15 September, Wayne led the Legion from Fort Defiance and marched unopposed for two days to the Miami capital of Kekionga

Kekionga (meaning "blackberry bush"), also known as KiskakonCharles R. Poinsatte, ''Fort Wayne During the Canal Era 1828-1855,'' Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1969, p. 1 or Pacan's Village, was the capital of the Miami tribe. It was l ...

, where they constructed Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

. Wayne appointed Hamtramck as commandant of Fort Wayne and departed in late October, arriving at Fort Greenville on 2 November. That winter, Wayne also reinforced his line of defensive forts with Fort St. Marys, Fort Loramie

Fort Loramie is a village in Shelby County, Ohio, United States, along Loramie Creek, a tributary of the Great Miami River in southwestern Ohio. It is 42 mi. northnorthwest of Dayton and 20 mi. east of the Ohio/Indiana border. The pop ...

, and Fort Piqua.

Aftermath

Throughout the campaign, Wayne's second in command, GeneralJames Wilkinson

James Wilkinson (March 24, 1757 – December 28, 1825) was an American soldier, politician, and double agent who was associated with several scandals and controversies.

He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, b ...

, secretly tried to undermine him. Wilkinson wrote anonymous negative letters to local newspapers about Wayne and spent years writing negative letters to politicians in Washington, D. C. Wayne was unaware as Wilkinson was recorded as being extremely polite to Wayne in person. Wilkinson was also a Spanish spy at the time and was even hired as an officer. Despite the significant US losses, Wilkinson regarded Fallen Timbers as a mere skirmish, saying the short battle "did not deserve the name of a battle." Years later, a Native American warrior reflected that Little Turtle had warned that the Great Spirit

The Great Spirit is the concept of a life force, a Supreme Being or god known more specifically as Wakan Tanka in Lakota,Ostler, Jeffry. ''The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee''. Cambridge University Press, ...

would hide in a cloud if they did not make peace with Wayne. The rainy start to the day was a sign that they would lose.

Parties began suing for peace in December. Antoine Lasselle arrived at Fort Wayne on 17 December with a group of Native Americans and Canadien

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fre ...

s. Within a month, most Miami had returned to Kekionga, and representatives of the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Odawa, and Wyandotte had sought out the Legion to "bury the hatchet." During the summer of 1795, the confederacy met with a U.S. delegation led by General Wayne to negotiate the Treaty of Greenville

The Treaty of Greenville, formally titled Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., was a 1795 treaty between the United States and indigenous nations of the Northwest Territory (now Midwestern United States), including the Wyandot and Delaware peoples, ...

, which was signed on 3 August. This treaty opened most of the modern U.S. state of Ohio to settlement, using the site of St. Clair's defeat as a reference point to draw a line near the current border of Ohio and Indiana. The Treaty of Greenville, along with Jay's Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

and Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795 by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

, set the terms of the peace and defined post-colonial relations among the U.S., Britain and Spain.

Henry Knox eventually alerted Wayne about Wilkinson's letters, and Wayne began an investigation. Wayne's suspicions were confirmed when Spanish couriers were intercepted with payments for Wilkinson. He attempted to court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

Wilkinson for his treachery. However, Wayne developed a stomach ulcer, complications from gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intensit ...

, and died on December 15, 1796 at Fort Presque Isle

Fort Presque Isle (also Fort de la Presqu'île) was a fort built by French soldiers in summer 1753 along Presque Isle Bay at present-day Erie, Pennsylvania, to protect the northern terminus of the Venango Path. It was the first of the French pos ...

.; there was no court-martial. Instead Wilkinson began his first tenure as Senior Officer of the Army, which lasted for about a year and a half. He continued to pass on intelligence to the Spanish in return for large sums in gold.Nelson, 1999

For decades following the battle, Odawas visited the battle site and left memorials at Turkey Foot Rock.

The Northwest would remain largely peaceful until the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. Wayne's aide-de-camp, William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, became territorial secretary, then a member of Congress, and was appointed as governor of the Indiana Territory

The Indiana Territory, officially the Territory of Indiana, was created by a United States Congress, congressional act that President of the United States, President John Adams signed into law on May 7, 1800, to form an Historic regions of the U ...

in 1801. He followed Thomas Jefferson's policy of incremental land purchases from Native American nations. Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

, a young Shawnee veteran of Fallen Timbers who refused to sign the Greenville Treaty, resisted this gradual removal with a new pan-tribal confederation. Harrison attacked this new confederation in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe

The Battle of Tippecanoe ( ) was fought on November 7, 1811, in Battle Ground, Indiana, between American forces led by then Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory and Native American forces associated with Shawnee leader Tecums ...

.

Many veterans of the Battle of Fallen Timbers would become known for their later accomplishments, including William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

, who co-led the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

, and William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, the 9th President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

. Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

, who watched his older brother Sauwauseekau die in battle, would later organize a new confederacy to oppose American Indian removals.

Legacy

On 14 September 1929, the

On 14 September 1929, the United States Post Office Department

The United States Post Office Department (USPOD; also known as the Post Office or U.S. Mail) was the predecessor of the United States Postal Service, in the form of a Cabinet department, officially from 1872 to 1971. It was headed by the postmas ...

issued a stamp commemorating the 135th anniversary of the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The post office issued a series of stamps referred to as the 'Two Cent Reds' by collectors, issued to commemorate the 150th Anniversaries of the many events that occurred during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–1783) and to honor those who were there. The Fallen Timbers stamp features an image of the Battle of Fallen Timbers Monument

The Battle of Fallen Timbers Monument or Anthony Wayne Memorial is a statuary group created by Bruce Saville.

It was dedicated in 1929 at the site of the Battle of Fallen Timbers which took place on August 20, 1794. At that battle General "Mad ...

, which was dedicated that same year.

National Park

For 200 years, the site of the Battle of Fallen Timbers was thought to be on the floodplain on the banks of theMaumee River

The Maumee River (pronounced ) ( sjw, Hotaawathiipi; mia, Taawaawa siipiiwi) is a river running in the United States Midwest from northeastern Indiana into northwestern Ohio and Lake Erie. It is formed at the confluence of the St. Joseph and ...

, based upon documentation such as the map above and to the right (location of Fallen Timbers Monument). Dr. G. Michael Pratt, an anthropologist and faculty member at Heidelberg University (Ohio)

Heidelberg University is a private university in Tiffin, Ohio. Founded in 1850, it was known as Heidelberg College until 1889 and from 1926 to 2009. It is affiliated with the United Church of Christ.

History

Heidelberg University was founded b ...

, correctly surmised the battlefield was 1/4 mile above the floodplain after considering documentation that described a ravine. The City of Toledo owned the area which was desirable for development. Although the City of Toledo initially refused archaeological exploration, in 1995 and 2001, Pratt was able to conduct archaeological surveys, which relied primarily on metal detection, which revealed musket balls, pieces of muskets, uniform buttons and a bayonet, confirming that major fighting had taken place at the site.

Because of Pratt's archaeological work and advocacy the Fallen Timbers Preservation Commission, the land was granted National Historic Site status in 1999. A federal grant allowed the Metroparks of the Toledo Area

Metroparks Toledo, officially the Metropolitan Park District of the Toledo Area, is a public park district consisting of park, parks, nature preserve, nature preserves, a botanical garden, trail, trail network and historic battlefield in Lucas Cou ...

to purchase the land where the artifacts were found in 2001, and the site was developed into a park in affiliation with the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

.

Fallen Timbers State Monument

The

The Ohio Historical Society

Ohio History Connection, formerly The Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society and Ohio Historical Society, is a nonprofit organization incorporated in 1885. Headquartered at the Ohio History Center in Columbus, Ohio, Ohio History Connect ...

maintains a small park at the site originally believed to have the main fighting (similar historic picture above and right). This site features the Battle of Fallen Timbers Monument

The Battle of Fallen Timbers Monument or Anthony Wayne Memorial is a statuary group created by Bruce Saville.

It was dedicated in 1929 at the site of the Battle of Fallen Timbers which took place on August 20, 1794. At that battle General "Mad ...

, honoring both Major General Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

and his army and Little Turtle

Little Turtle ( mia, Mihšihkinaahkwa) (1747 July 14, 1812) was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader ...

and his warriors. Additionally, there are plaques describing the Battle of Fallen Timbers and honoring the several Indian tribes that participated. The main monument has tributes inscribed on each of its four sides honoring in turn, Wayne, the fallen soldiers, Little Turtle, and his Indian warriors. The park is located near Maumee in Lucas County. Turkey Foot Rock, marking the death place of Turkey Foot, is also at the site.

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

Battle of Fallen Timbers

– Chickasaw.TV

Battle of Fallen Timbers Battle of Fallen Timbers

–

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

Fallen Timbers Battlefield and Fort Miamis National Historic Site

from

National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

The Fallen Timbers battlefield today

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110421223417/http://fallentimbersbattlefield.com/ Battle of Fallen Timbers – The Toledo Metroparks* {{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Fallen Timbers 1794 in the United States

Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between Indigenous peoples of North America, Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their Kingdom of Gre ...

Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between Indigenous peoples of North America, Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their Kingdom of Gre ...

Conflicts in 1794

History of Toledo, Ohio

Ohio History Connection

Parks in Ohio

Pre-statehood history of Ohio

Protected areas of Lucas County, Ohio

William Henry Harrison

1794 in the Northwest Territory

Native American history of Ohio