Fabre Geffrard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Guillaume Fabre Nicolas Geffrard (19 September 1806 – 31 December 1878) was a

In 1859, Geffrard made the first attempt in negotiating with the

In 1859, Geffrard made the first attempt in negotiating with the

By the eighth month of Geffrard's presidency,

By the eighth month of Geffrard's presidency,

mulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese is ...

general in the Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

an army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and President of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

from 1859 until his deposition in 1867. On 18 April 1852, Faustin Soulouque

Faustin-Élie Soulouque (15 August 1782 – 3 August 1867) was a Haitian politician and military commander who served as President of Haiti from 1847 to 1849 and Emperor of Haiti from 1849 to 1859.

Soulouque was a general in the Haitian Army w ...

made him Duke of Tabara. After collaborating in a coup to remove Faustin Soulouque

Faustin-Élie Soulouque (15 August 1782 – 3 August 1867) was a Haitian politician and military commander who served as President of Haiti from 1847 to 1849 and Emperor of Haiti from 1849 to 1859.

Soulouque was a general in the Haitian Army w ...

from power in order to return Haiti to the social and political control of the colored elite, Geffrard was made president in 1859. To placate the peasants he renewed the practice of selling state-owned lands and ended a schism with the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

which then took on an important role in improving education. After surviving several rebellions, he was overthrown by Major Sylvain Salnave

Sylvain Salnave (February 6, 1827 – January 15, 1870) was a Haitian general who served as the President of Haïti from 1867 to 1869. He was elected president after he led the overthrow of President Fabre Geffrard. During his term there were cons ...

in 1867.

Life prior to presidency

Geffrard was a son of Nicolas Geffrard, a general of the Armee indigene during the Haitian Revolution and a signatory of theHaitian Declaration of Independence

The Haitian Declaration of Independence was proclaimed on 1 January 1804 in the port city of Gonaïves by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, marking the end of 13-year long Haitian Revolution. The declaration marked Haiti becoming the first independent nati ...

who was assassinated a few months before Fabre's birth. Fabre Geffrard is then adopted by his uncle, Colonel Fabre. Geffrard left the college in the town of Cayes in 1821 and enlisted in the army. When General Charles Rivière-Hérard

Charles Rivière-Hérard also known as Charles Hérard aîné (16 February 1789 – 31 August 1850) was an officer in the Haitian Army under Alexandre Pétion during his struggles against Henri Christophe. He was declared President of Haiti on ...

launched a rebellion against dictator Jean-Pierre Boyer

Jean-Pierre Boyer (15 February 1776 – 9 July 1850) was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, and President of Haiti from 1818 to 1843. He reunited the north and south of the country into the Republic of Haiti in 1820 and also annex ...

in 1843, Geffrard joined him and was appointed lieutenant-colonel. He is then sent to the town of Jérémie

Jérémie ( ht, Jeremi) is a commune and capital city of the Grand'Anse department in Haiti. It had a population of about 31,000 at the 2003 census. It is relatively isolated from the rest of the country. The Grande-Anse River flows near the ...

where he defeated Boyer's troops, who he then pursued as far as the Tiburon peninsula. After this military triumph he was elevated to the rank of brigadier general in 1844. The new president, Jean-Baptiste Riché

Jean-Baptiste Riché, Count of Grande-Riviere-du-Nord (1780 – February 27, 1847) was a career officer and general in the Haitian Army. He was made President of Haiti on March 1, 1846.

Life

Riché was born free, the son of a prominent free ...

feared Geffrard's popularity, and had him arrested to try to bring him to justice, but the court martial acquitted him for misconduct. In 1849, under the reign of Soulouque

Faustin-Élie Soulouque (15 August 1782 – 3 August 1867) was a Haitian politician and military commander who served as President of Haiti from 1847 to 1849 and Emperor of Haiti from 1849 to 1859.

Soulouque was a general in the Haitian Army wh ...

, Geffrard commanded an expedition against the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

during which he was wounded at the Battle of Azua

The Battle of Azua was the first major battle of the Dominican War of Independence and was fought on the 19 March 1844, at Azua de Compostela, Azua Province. A force of some 2,200 Dominican troops, a portion of the Army of the South, led by Gene ...

. He held the highest positions in the army under the government of Faustin Soulouque and under the Empire. In 1849 Soulouque become Emperor Faustin I and appointed Geffrard to command a division of the army during the first war against Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), in which he gained fame by his victory at La Tabarra

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figur ...

. During the second war against Santo Domingo (1856) General Geffrard distinguished himself on several occasions, in particular thanks to the skillful direction of the artillery in Banico. He was thus titled Duke of Tabarre for his military success. But as this regime became unpopular, Geffrard was threatened by Emperor Faustin I. Arrested, he escaped and organizes a revolt, which led to the fall of the Empire. On 15 January 1859, minutes after the abdication of Emperor Faustin I, he proclaimed the Third Republic and was elected president.

Presidency

His first act as president was to cut the army in half from 30,000 to 15,000. He also formed his own presidential guards called ''Les Tirailleurs de la Garde

A tirailleur (), in the Napoleonic era, was a type of light infantry trained to skirmish ahead of the main columns. Later, the term "''tirailleur''" was used by the French Army as a designation for indigenous infantry recruited in the French c ...

'', who were trained under him personally.

In June 1859, Geffrard founded the National Law School and reinstituted the Medical School that Boyer

Boyer () is a French surname. In rarer cases, it can be a corruption or deliberate alteration of other names.

Origins and statistics

Boyer is found traditionally along the Mediterranean (Provence, Languedoc), the Rhône valley, Auvergne, Limou ...

began. His ministers of Education, Jean Simon Elie-Dubois and François Elie-Dubois, modernized and established many lycea in Jacmel

Jacmel (; ht, Jakmèl) is a commune in southern Haiti founded by the Spanish in 1504 and repopulated by the French in 1698. It is the capital of the department of Sud-Est, 24 miles (39 km) southwest of Port-au-Prince across the Tiburon Peninsula ...

, Jérémie

Jérémie ( ht, Jeremi) is a commune and capital city of the Grand'Anse department in Haiti. It had a population of about 31,000 at the 2003 census. It is relatively isolated from the rest of the country. The Grande-Anse River flows near the ...

, Saint-Marc

Saint-Marc ( ht, Sen Mak) is a commune in western Haiti in Artibonite departement. Its geographic coordinates are . At the 2003 Census the commune had 160,181 inhabitants. It is one of the biggest cities, second to Gonaïves, between Port-au-P ...

, and Gonaïves

Gonaïves (; ht, Gonayiv, ) is a commune in northern Haiti, and the capital of the Artibonite department of Haiti. It has a population of about 300,000 people, but current statistics are unclear, as there has been no census since 2003.

History ...

. On 10 October 1863, he reintroduced the colonial law that required roads to be built and maintained. He also revived the policy of former rulers Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent First Empire of Haiti, Haiti under the Constitution of Haiti, 1 ...

, Alexandre Pétion

Alexandre Sabès Pétion (; April 2, 1770 – March 29, 1818) was the first president of the Republic of Haiti from 1807 until his death in 1818. He is acknowledged as one of Haiti's founding fathers; a member of the revolutionary quartet that ...

and Jean-Pierre Boyer

Jean-Pierre Boyer (15 February 1776 – 9 July 1850) was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, and President of Haiti from 1818 to 1843. He reunited the north and south of the country into the Republic of Haiti in 1820 and also annex ...

of recruiting African Americans to settle in Haiti. In May 1861, a group of African Americans led by James Theodore Holly

James Theodore Augustus Holly (3 October 1829 in Washington, D.C. – 13 March 1911 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti) was the first African-American bishop in the Protestant Episcopal church, and spent most of his episcopal career as missionary bishop of ...

settled east of Croix-des-Bouquets

Croix-des-Bouquets (, ; ht, Kwadèbouke or ) is a commune in the Ouest department of Haiti. It is located to the northeast of Haiti's capital city, Port-au-Prince. Originally located on the shore, it was relocated inland after the 1770 Port- ...

. However, by 1862, Geffrard began to examine the constitution and eliminated the legislature to his own benefit. He first gave himself a raise, 2 plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

s, and paid for his personal luxuries with hospital funds and army funds. In 1863, he reformed the monetary system to that of the present day.

Geffrard was a Catholic, which made him renounce any form of the Voodoo

Voodoo may refer to:

Religions

* African or West African Vodun, practiced by Gbe-speaking ethnic groups

* African diaspora religions, a list of related religions sometimes called Vodou/Voodoo

** Candomblé Jejé, also known as Brazilian Vodu ...

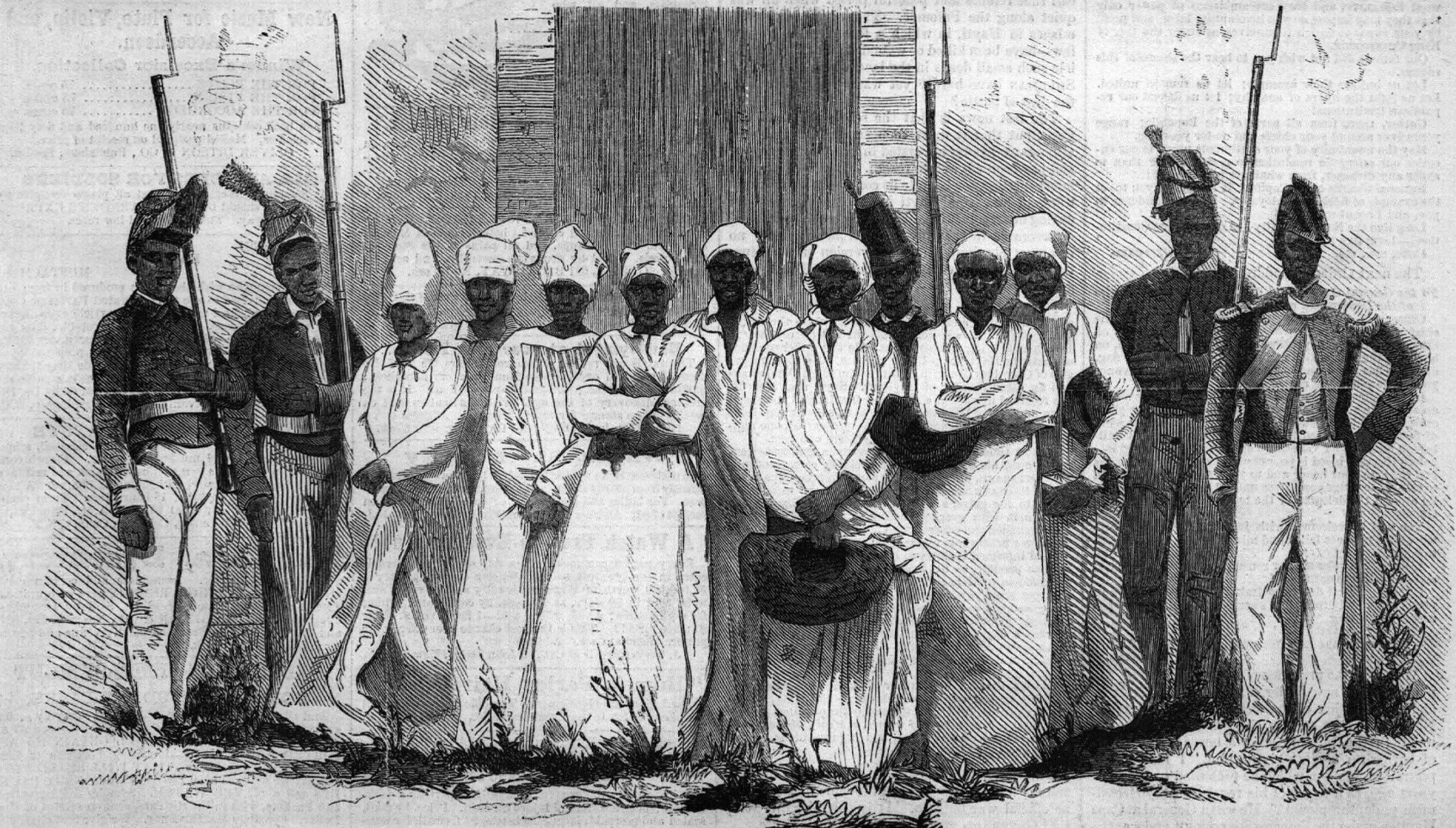

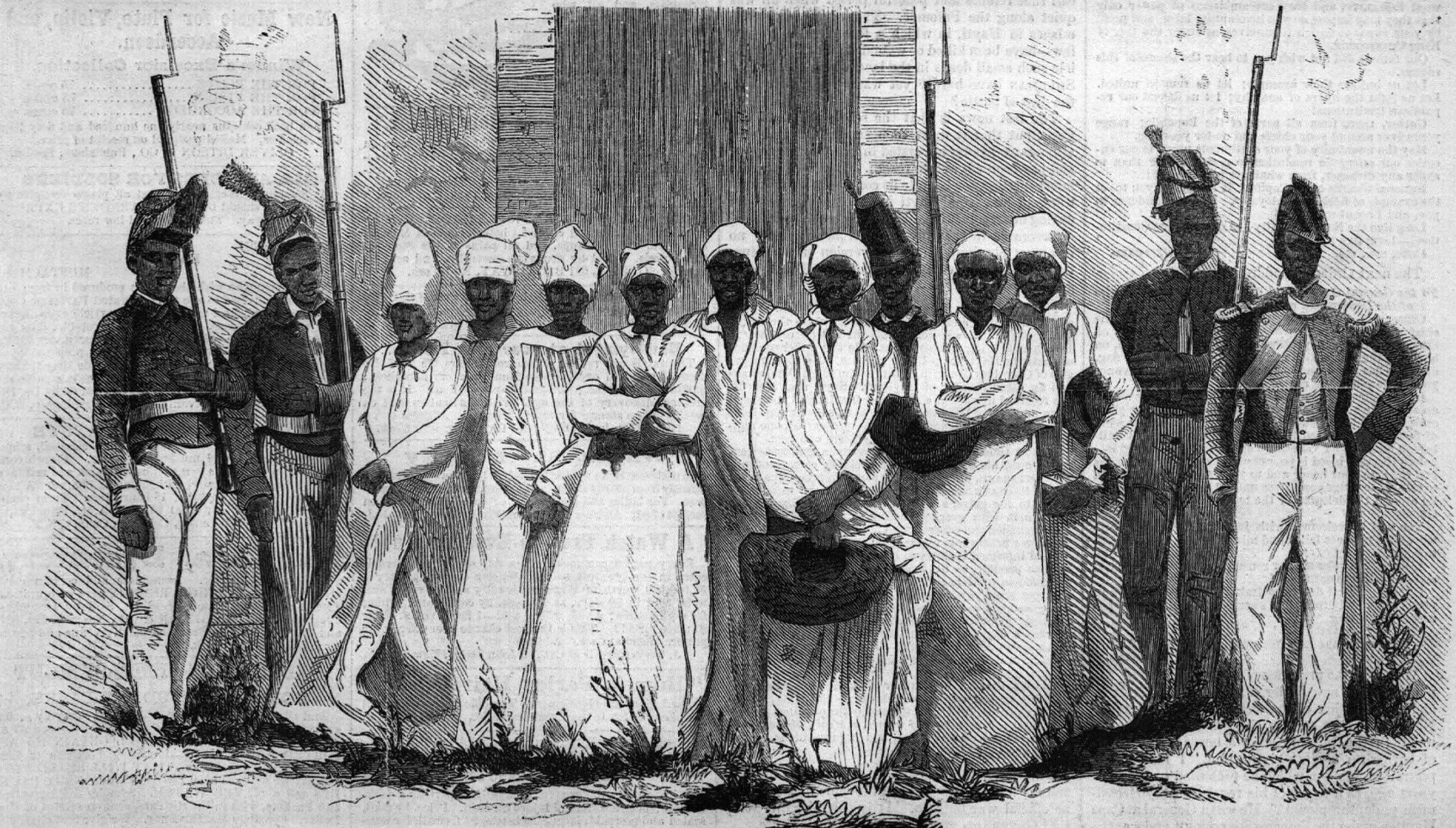

faith. He gave orders to demolish altars, drums, and any other instruments used in ceremonies. In 1863, a six-year-old girl was allegedly killed by Voodoo practitioners in a gruesome fashion. Geffrard ordered a deep investigation and a public execution was held. This case became the famous ''Affaire de Bizoton'', which was featured in a British minister's best-selling book.

In 1859, Geffrard made the first attempt in negotiating with the

In 1859, Geffrard made the first attempt in negotiating with the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

under the regime of Pedro Santana

Pedro Santana y Familias, 1st Marquess of Las Carreras (June 29, 1801June 14, 1864) was a Dominican military commander and royalist politician who served as the president of the junta that had established the First Dominican Republic, a pre ...

. Unfortunately, in March 1861, Pedro gave his country back to Queen Isabella II of Spain, thus making Haitian officials nervous about having a European power back on their borders. In May of that year, guerilla war broke out in Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

against Spain. Geffrard sent his personal guards and men to help out the rebels against Spanish troops, but in July 1861, following the execution of Francisco del Rosario Sánchez

Francisco del Rosario Sánchez (March 9, 1817 – July 4, 1861) was a Dominican revolutionary, politician, and former president of the Dominican Republic. He is considered by Dominicans as the second leader of the 1844 Dominican War of Independen ...

, Spain gave Haiti an ultimatum for participating and supporting the Dominican rebels. In the end, Geffrard agreed to surrender to Spanish demands and dropped all intervention within Spanish territory in the east. This episode left many Haitians humiliated and angry at Geffrard because he backed down to a European nation while Faustin Soulouque

Faustin-Élie Soulouque (15 August 1782 – 3 August 1867) was a Haitian politician and military commander who served as President of Haiti from 1847 to 1849 and Emperor of Haiti from 1849 to 1859.

Soulouque was a general in the Haitian Army w ...

would have never accepted it.

Geffrard, like many Haitians, supported the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

movement in the United States and held a state funeral for the abolitionist John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

, who was hanged for leading an armed insurrection against the United States government in 1859. With the secession of the slave-owning Southern states in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Haiti was granted diplomatic recognition by the United States. During the war, Spanish and British colonial officials in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, the Bahamas and neighboring Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

passively sided with the Confederacy, harboring Confederate commerce-raiders and blockade-runners. By contrast, Haiti was the one part of the Caribbean (with the exception of Danish St. Thomas) where the United States Navy was welcome, and Cap-Haïtien

Cap-Haïtien (; ht, Kap Ayisyen; "Haitian Cape"), typically spelled Cape Haitien in English and often locally referred to as or , is a commune of about 190,000 people on the north coast of Haiti and capital of the department of Nord. Previousl ...

served as the headquarters of its West Indian Squadron, which helped maintain the Union blockade in the Florida Straits

The Straits of Florida, Florida Straits, or Florida Strait ( es, Estrecho de Florida) is a strait located south-southeast of the North American mainland, generally accepted to be between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, and between th ...

. Haiti also took advantage of the war to become a major exporter of cotton to the United States, and Geffrard imported gins and technicians to increase production. However, the crops failed in 1865 and 1866, and by that point the United States was again exporting cotton.

Failed coups against Geffrard

By the eighth month of Geffrard's presidency,

By the eighth month of Geffrard's presidency, Faustin Soulouque

Faustin-Élie Soulouque (15 August 1782 – 3 August 1867) was a Haitian politician and military commander who served as President of Haiti from 1847 to 1849 and Emperor of Haiti from 1849 to 1859.

Soulouque was a general in the Haitian Army w ...

's minister of interior, Guerrier Prophète, began to lay out his plan to overthrow Geffrard. Fortunately for Geffrard, his plan was picked up by Geffrard's guards and Prophète was exiled. In September 1859, Geffrard's daughter Madame Cora Manneville-Blanfort was assassinated by Timoleon Vanon. In 1861, General Legros tried to take over the weaponry storage but was detained by government forces. In 1862, Etienne Salomon tried to rally the rural community to revolt against Geffrard, but was instead shot and killed. In 1863, Aimé Legros gathered troops to overthrow Geffrard, but his troops betrayed him, and he was shot. In 1864, the elite community in Port-au-Prince

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The metropolitan area is define ...

tried to take over the weaponry storage, but the conspirators were later prosecuted and sentenced to jail.

In 1867, Geffrard's bodyguards, ''Tirailleurs'', betrayed him and tried to assassinate him inside the national palace.

Overthrow

In 1865, MajorSylvain Salnave

Sylvain Salnave (February 6, 1827 – January 15, 1870) was a Haitian general who served as the President of Haïti from 1867 to 1869. He was elected president after he led the overthrow of President Fabre Geffrard. During his term there were cons ...

began his takeover of the North and Artibonite part of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

. By 15 May both Geffrard and his government troops clashed with Salnave Northern troops. After using the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

for gunboat diplomacy with Salnave, the Geffrard regime was in ruins, especially financially. He re-opened old wounds between North, West, and South Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

ans and brought foreigners into domestic affairs. In 1866, a huge fire engulfed hundreds of houses and businesses. In March 1867, Geffrard and his family disguised themselves and fled to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, where he died in Kingston in 1878.

Family

Geffrard, with his wife Marguerite Lorvana McIntosh, had several children: * Laurinska Madiou * Celimene Cesvet * Cora Manneville-Blandfort (d. 1859) * Marguerite Zéïla Geffrard * Claire Geffrard * Angèle Dupuy * Charles Nicholas Clodomir Fabre Geffrard (1833-1859)Footnotes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Geffrard, Fabre Presidents of Haiti 1806 births 1878 deaths Haitian military leaders Haitian people of Mulatto descent Haitian exiles Haitian emigrants to Jamaica People from Nippes Haitian Roman Catholics