The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic

intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. More generally, it can b ...

and

security

Security is protection from, or resilience against, potential harm (or other unwanted coercive change) caused by others, by restraining the freedom of others to act. Beneficiaries (technically referents) of security may be of persons and social ...

service of the United States and its principal

federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the

United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United State ...

, the FBI is also a member of the

U.S. Intelligence Community

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and reports to both the

Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

and the

Director of National Intelligence

The director of national intelligence (DNI) is a senior, cabinet-level United States government official, required by the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 to serve as executive head of the United States Intelligence Commu ...

.

A leading U.S.

counterterrorism

Counterterrorism (also spelled counter-terrorism), also known as anti-terrorism, incorporates the practices, military tactics, techniques, and strategies that Government, governments, law enforcement, business, and Intelligence agency, intellig ...

,

counterintelligence

Counterintelligence is an activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting activities to prevent espionage, sabotage, assassinations or ot ...

, and criminal investigative organization, the FBI has

jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

Jur ...

over violations of more than 200 categories of

federal crimes

In the United States, a federal crime or federal offense is an act that is made illegal by U.S. federal legislation enacted by both the United States Senate and United States House of Representatives and signed into law by the president. Prosec ...

.

Although many of the FBI's functions are unique, its activities in support of

national security

National security, or national defence, is the security and defence of a sovereign state, including its citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of government. Originally conceived as protection against military atta ...

are comparable to those of the British

MI5

The Security Service, also known as MI5 ( Military Intelligence, Section 5), is the United Kingdom's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), Go ...

and

NCA; the New Zealand

GCSB

The Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) ( mi, Te Tira Tiaki) is the public-service department of New Zealand charged with promoting New Zealand's national security by collecting and analysing information of an intelligence nature. ...

and the Russian

FSB. Unlike the

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA), which has no law enforcement authority and is focused on intelligence collection abroad, the FBI is primarily a domestic agency, maintaining 56

field offices in major cities throughout the United States, and more than 400 resident agencies in smaller cities and areas across the nation. At an FBI field office, a senior-level FBI officer concurrently serves as the representative of the

Director of National Intelligence

The director of national intelligence (DNI) is a senior, cabinet-level United States government official, required by the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 to serve as executive head of the United States Intelligence Commu ...

.

Despite its domestic focus, the FBI also maintains a significant international footprint, operating 60 Legal Attache (LEGAT) offices and 15 sub-offices in

U.S. embassies and consulates across the globe. These foreign offices exist primarily for the purpose of coordination with foreign security services and do not usually conduct unilateral operations in the host countries. The FBI can and does at times carry out secret activities overseas, just as the CIA has a

limited domestic function; these activities generally require coordination across government agencies.

The FBI was established in 1908 as the Bureau of Investigation, the BOI or BI for short. Its name was changed to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1935. The FBI headquarters is the

J. Edgar Hoover Building

The J. Edgar Hoover Building is a low-rise office building located at 935 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., in the United States. It is the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Planning for the building began in ...

in

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

Mission, priorities and budget

Mission

The mission of the FBI is:

Protect the American people and uphold the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

Priorities

Currently, the FBI's top priorities are:

* Protect the United States from

terrorist attacks

The following is a list of terrorist incidents that have not been carried out by a state or its forces (see state terrorism and state-sponsored terrorism). Assassinations are listed at List of assassinated people.

Definitions of terrori ...

* Protect the United States against foreign intelligence operations, espionage, and cyber operations

*Combat significant cyber criminal activity

* Combat public

corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

at all levels

* Protect

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

* Combat transnational criminal enterprises

* Combat major

white-collar crime

The term "white-collar crime" refers to financially motivated, nonviolent or non-directly violent crime committed by individuals, businesses and government professionals. It was first defined by the sociologist Edwin Sutherland in 1939 as "a ...

* Combat significant

violent crime

A violent crime, violent felony, crime of violence or crime of a violent nature is a crime in which an offender or perpetrator uses or threatens to use harmful force upon a victim. This entails both crimes in which the violence, violent act is t ...

Budget

In the fiscal year 2019, the Bureau's total budget was approximately $9.6 billion.

In the Authorization and Budget Request to Congress for fiscal year 2021, the FBI asked for $9,800,724,000. Of that money, $9,748,829,000 would be used for Salaries and Expenses (S&E) and $51,895,000 for Construction.

The S&E program saw an increase of $199,673,000.

History

Background

In 1896, the

National Bureau of Criminal Identification The National Bureau of Criminal Identification (NBCI), also called the National Bureau of Identification, was an agency founded by the National Chiefs of Police Union in 1896, and opened in 1897, to record identifying information on criminals and s ...

was founded, which provided agencies across the country with information to identify known criminals. The

1901 assassination of President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

created a perception that the United States was under threat from

anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

. The Departments of Justice and

Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

had been keeping records on anarchists for years, but President

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

wanted more power to monitor them.

The Justice Department had been tasked with

the regulation of interstate commerce since 1887, though it lacked the staff to do so. It had made little effort to relieve its staff shortage until the

Oregon land fraud scandal

The Oregon land fraud scandal of the early 20th century involved U.S. government land grants in the U.S. state of Oregon being illegally obtained with the assistance of public officials. Most of Oregon's U.S. congressional delegation received ...

at the turn of the 20th century. President Roosevelt instructed Attorney General

Charles Bonaparte to organize an autonomous investigative service that would report only to the

Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

.

Bonaparte reached out to other agencies, including the

U.S. Secret Service

The United States Secret Service (USSS or Secret Service) is a federal law enforcement agency under the Department of Homeland Security charged with conducting criminal investigations and protecting U.S. political leaders, their families, and ...

, for personnel, investigators in particular. On May 27, 1908, Congress forbade this use of Treasury employees by the Justice Department, citing fears that the new agency would serve as a

secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

department.

Again at Roosevelt's urging, Bonaparte moved to organize a formal Bureau of Investigation, which would then have its own staff of

special agents.

Creation of BOI

The Bureau of Investigation (BOI) was created on July 26, 1908. Attorney General Bonaparte, using Department of Justice expense funds,

hired thirty-four people, including some veterans of the Secret Service,

to work for a new investigative agency. Its first "chief" (the title is now "director") was

Stanley Finch

Stanley Wellington Finch (July 20, 1872 – 22 November 1951) was the first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Bureau of Investigation (1908–1912), which would eventually become the FBI.

Life

Finch was born in Monticello, New Y ...

. Bonaparte notified the Congress of these actions in December 1908.

The bureau's first official task was visiting and making surveys of the houses of prostitution in preparation for enforcing the "White Slave Traffic Act" or

Mann Act

The White-Slave Traffic Act, also called the Mann Act, is a United States federal law, passed June 25, 1910 (ch. 395, ; ''codified as amended at'' ). It is named after Congressman James Robert Mann of Illinois.

In its original form the act mad ...

, passed on June 25, 1910. In 1932, the bureau was renamed the United States Bureau of Investigation.

Creation of FBI

The following year, 1933, the BOI was linked to the

Bureau of Prohibition

The Bureau of Prohibition (or Prohibition Unit) was the United States federal law enforcement agency formed to enforce the National Prohibition Act of 1919, commonly known as the Volstead Act, which enforced the 18th Amendment to the United St ...

and rechristened the Division of Investigation (DOI); it became an independent service within the Department of Justice in 1935.

In the same year, its name was officially changed from the Division of Investigation to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

J. Edgar Hoover as FBI director

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

served as FBI director from 1924 to 1972, a combined 48 years with the BOI, DOI, and FBI. He was chiefly responsible for creating the Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory, or the

FBI Laboratory

The FBI Laboratory (also called the Laboratory Division) is a division within the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation that provides forensic analysis support services to the FBI, as well as to state and local law enforcement agencies ...

, which officially opened in 1932, as part of his work to professionalize investigations by the government. Hoover was substantially involved in most major cases and projects that the FBI handled during his tenure. But as detailed below, his proved to be a highly controversial tenure as Bureau director, especially in its later years. After Hoover's death, Congress passed legislation that limited the tenure of future FBI directors to ten years.

Early homicide investigations of the new agency included the

Osage Indian murders

The Osage Indian murders were a series of murders of Osage Native Americans in Osage County, Oklahoma, during the 1910s–1930s; newspapers described the increasing number of unsolved murders as the Reign of Terror, lasting from 1921 to 1926. So ...

. During the "War on Crime" of the 1930s, FBI agents apprehended or killed a number of notorious criminals who committed kidnappings, bank robberies, and murders throughout the nation, including

John Dillinger

John Herbert Dillinger (June 22, 1903 – July 22, 1934) was an American gangster during the Great Depression. He led the Dillinger Gang, which was accused of robbing 24 banks and four police stations. Dillinger was imprisoned several times and ...

,

"Baby Face" Nelson,

Kate "Ma" Barker,

Alvin "Creepy" Karpis, and

George "Machine Gun" Kelly Machine Gun Kelly most often refers to:

* Machine Gun Kelly (gangster) (1900–1954), American gangster.

* Machine Gun Kelly (musician) (born 1990), American rapper.

Machine Gun Kelly may also refer to:

* ''Machine-Gun Kelly'' (film), 1958 film a ...

.

Other activities of its early decades focused on the scope and influence of the white supremacist group

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, a group with which the FBI was evidenced to be working in the

Viola Liuzzo

Viola Fauver Liuzzo (née Gregg; April 11, 1925 – March 25, 1965) was an American civil rights activist. In March 1965, Liuzzo heeded the call of Martin Luther King Jr. and traveled from Detroit, Michigan, to Selma, Alabama, in the wake of the ...

lynching case. Earlier, through the work of

Edwin Atherton

Edwin Newton Atherton (October 12, 1896 – August 31, 1944) served as a foreign service officer, Bureau of Investigation agent, private investigator, and later, appointed head of the college athletics organization, the Pacific Coast Conference ...

, the BOI claimed to have successfully apprehended an entire army of Mexican neo-revolutionaries under the leadership of General

Enrique Estrada

Enrique Estrada Reynoso (1890–1942) was a Mexican General, politician, and Secretary of National Defense.

Born in Moyahua, Zacatecas in 1890. His parents were José Camilo Estrada Haro and Micaela Reynoso Espitia. His older brother was Roque E ...

in the mid-1920s, east of San Diego, California.

Hoover began using

wiretapping

Telephone tapping (also wire tapping or wiretapping in American English) is the monitoring of telephone and Internet-based conversations by a third party, often by covert means. The wire tap received its name because, historically, the monitorin ...

in the 1920s during

Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

to arrest bootleggers.

In the 1927 case ''

Olmstead v. United States

''Olmstead v. United States'', 277 U.S. 438 (1928), was a decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, on the matter of whether wiretapping of private telephone conversations, obtained by federal agents without a search warrant and subsequ ...

'', in which a bootlegger was caught through telephone tapping, the

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

ruled that FBI wiretaps did not violate the

Fourth Amendment as unlawful search and seizure, as long as the FBI did not break into a person's home to complete the tapping.

After Prohibition's repeal,

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

passed the

Communications Act of 1934

The Communications Act of 1934 is a United States federal law signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 19, 1934 and codified as Chapter 5 of Title 47 of the United States Code, et seq. The Act replaced the Federal Radio Commission with ...

, which outlawed non-consensual phone tapping, but did allow bugging.

In the 1939 case ''Nardone v. United States'', the court ruled that due to the 1934 law, evidence the FBI obtained by phone tapping was inadmissible in court.

After ''

Katz v. United States

''Katz v. United States'', 389 U.S. 347 (1967), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court redefined what constitutes a "search" or "seizure" with regard to the protections of the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ...

'' (1967) overturned ''Olmstead'', Congress passed the

Omnibus Crime Control Act

The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 (, codified at ''et seq.'') was legislation passed by the Congress of the United States and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson that established the Law Enforcement Assistance Admi ...

, allowing public authorities to tap telephones during investigations, as long as they obtained warrants beforehand.

National security

Beginning in the 1940s and continuing into the 1970s, the bureau investigated cases of

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

against the United States and its allies. Eight

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

agents who had planned

sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identitie ...

operations against American targets were arrested, and six were executed (''

Ex parte Quirin'') under their sentences. Also during this time, a joint US/UK code-breaking effort called "The

Venona Project

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (later absorbed by the National Security Agency), which ran from February 1, 1943, until Octob ...

"—with which the FBI was heavily involved—broke Soviet diplomatic and intelligence communications codes, allowing the US and British governments to read Soviet communications. This effort confirmed the existence of Americans working in the United States for Soviet intelligence.

Hoover was administering this project, but he failed to notify the

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) of it until 1952. Another notable case was the arrest of Soviet spy

Rudolf Abel

Rudolf Ivanovich Abel (russian: Рудольф Иванович Абель), real name William August Fisher (11 July 1903 – 15 November 1971), was a Soviet intelligence officer. He adopted his alias when arrested on charges of conspiracy by ...

in 1957. The discovery of Soviet spies operating in the US motivated Hoover to pursue his longstanding concern with the threat he perceived from the

American Left

The American Left consists of individuals and groups that have sought egalitarian changes in the economic, political and cultural institutions of the United States. Various subgroups with a national scope are active. Liberals and progressives b ...

.

Japanese American internment

In 1939, the Bureau began compiling a

custodial detention list with the names of those who would be taken into custody in the event of war with Axis nations. The majority of the names on the list belonged to

Issei

is a Japanese-language term used by ethnic Japanese in countries in North America and South America to specify the Japanese people who were the first generation to immigrate there. are born in Japan; their children born in the new country are ...

community leaders, as the FBI investigation built on an existing

Naval Intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

index that had focused on

Japanese American

are Americans of Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 census, they have declined in number to constitute the sixth largest Asi ...

s in Hawaii and the West Coast, but many

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

and

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

nationals also found their way onto the

FBI Index

The FBI Indexes, or Index List, was a system used to track American citizens and other people by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) before the adoption of computerized databases. The Index List was originally made of paper index cards, firs ...

list. Robert Shivers, head of the Honolulu office, obtained permission from Hoover to start detaining those on the list on December 7, 1941, while bombs were still falling over

Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

.

Mass arrests and searches of homes (in most cases conducted without warrants) began a few hours after the attack, and over the next several weeks more than 5,500 Issei men were taken into FBI custody. On February 19, 1942, President

Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

issued

Executive Order 9066

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the secretary of war to prescribe certain ...

, authorizing the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. FBI Director Hoover opposed the subsequent mass removal and confinement of Japanese Americans authorized under Executive Order 9066, but Roosevelt prevailed. The vast majority went along with the subsequent exclusion orders, but in a handful of cases where Japanese Americans refused to obey the new military regulations, FBI agents handled their arrests.

The Bureau continued surveillance on Japanese Americans throughout the war, conducting background checks on applicants for resettlement outside camp, and entering the camps (usually without the permission of

War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was t ...

officials) and grooming informants to monitor dissidents and "troublemakers". After the war, the FBI was assigned to protect returning Japanese Americans from attacks by hostile white communities.

Sex deviates program

According to Douglas M. Charles, the FBI's "sex deviates" program began on April 10, 1950, when J. Edgar Hoover forwarded to the White House, to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, and to branches of the armed services a list of 393 alleged federal employees who had allegedly been arrested in Washington, D.C., since 1947, on charges of "sexual irregularities". On June 20, 1951, Hoover expanded the program by issuing a memo establishing a "uniform policy for the handling of the increasing number of reports and allegations concerning present and past employees of the United States Government who assertedly

icare sex deviates." The program was expanded to include non-government jobs. According to

Athan Theoharis

Athan George Theoharis (August 3, 1936 – July 3, 2021) was an American historian, professor of history at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. As well as his extensive teaching career, he was noteworthy as an expert on the Federal B ...

, "In 1951 he

ooverhad unilaterally instituted a Sex Deviates program to purge alleged homosexuals from any position in the federal government, from the lowliest clerk to the more powerful position of White house aide." On May 27, 1953,

Executive Order 10450

President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10450 on April 27, 1953. Effective May 27, 1953, it revoked President Truman's Executive Order 9835 of 1947, and dismantled its Loyalty Review Board program. Instead it charged the heads of f ...

went into effect. The program was expanded further by this executive order by making all federal employment of homosexuals illegal. On July 8, 1953, the FBI forwarded to the U.S. Civil Service Commission information from the sex deviates program. In 1977–1978, 300,000 pages, collected between 1930 and the mid-1970s, in the sex deviates program were destroyed by FBI officials.

Civil rights movement

During the 1950s and 1960s, FBI officials became increasingly concerned about the influence of civil rights leaders, whom they believed either had communist ties or were unduly influenced by communists or "

fellow traveler

The term ''fellow traveller'' (also ''fellow traveler'') identifies a person who is intellectually sympathetic to the ideology of a political organization, and who co-operates in the organization's politics, without being a formal member of that o ...

s". In 1956, for example, Hoover sent an open letter denouncing Dr.

T. R. M. Howard

Theodore Roosevelt Mason Howard (March 4, 1908 – May 1, 1976) was an American civil rights leader, fraternal organization leader, entrepreneur and surgeon. He was a mentor to activists such as Medgar Evers, Charles Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, ...

, a civil rights leader, surgeon, and wealthy entrepreneur in Mississippi who had criticized FBI inaction in solving recent murders of

George W. Lee

George Wesley Lee (December 25, 1903 – May 7, 1955) was an African-American civil rights leader, minister, and entrepreneur. He was a vice president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership and head of the Belzoni, Mississippi, branch of ...

,

Emmett Till

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941August 28, 1955) was a 14-year-old African American boy who was abducted, tortured, and lynched in Mississippi in 1955, after being accused of offending a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, in her family's grocery ...

, and other blacks in the South. The FBI carried out controversial

domestic surveillance in an operation it called the

COINTELPRO

COINTELPRO ( syllabic abbreviation derived from Counter Intelligence Program; 1956–1971) was a series of covert and illegal projects actively conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrati ...

, from "COunter-INTELligence PROgram".

It was to investigate and disrupt the activities of dissident political organizations within the United States, including both militant and non-violent organizations. Among its targets was the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civi ...

, a leading civil rights organization whose clergy leadership included the Rev. Dr.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, who is addressed in more detail below.

The FBI frequently investigated King. In the mid-1960s, King began to criticize the Bureau for giving insufficient attention to the use of terrorism by white supremacists. Hoover responded by publicly calling King the most "notorious liar" in the United States. In his 1991 memoir, ''

Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' journalist

Carl Rowan

Carl Thomas Rowan (August 11, 1925 – September 23, 2000) was a prominent American journalist, author and government official who published columns syndicated across the U.S. and was at one point the highest ranking African American in the United ...

asserted that the FBI had sent at least one anonymous letter to King encouraging him to commit suicide.

Historian

Taylor Branch

Taylor Branch (born January 14, 1947) is an American author and historian who wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning trilogy chronicling the life of Martin Luther King Jr. and much of the history of the American civil rights movement. The final volume o ...

documents an anonymous November 1964 "suicide package" sent by the Bureau that combined a letter to the civil rights leader telling him "You are done. There is only one way out for you." with audio recordings of King's sexual indiscretions.

In March 1971, the residential office of an FBI agent in

Media, Pennsylvania

Media is a borough in and the county seat of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. It is located about west of Philadelphia, the sixth most populous city in the nation with 1.6 million residents as 2020. It is part of the Delaware Valley metropolita ...

was burgled by a group calling itself the

Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI

The Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI was an activist group operational in the US during the early 1970s. Their only known action was breaking into a two-man Media, Pennsylvania, office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and s ...

. Numerous files were taken and distributed to a range of newspapers, including ''

The Harvard Crimson

''The Harvard Crimson'' is the student newspaper of Harvard University and was founded in 1873. Run entirely by Harvard College undergraduates, it served for many years as the only daily newspaper in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Beginning in the f ...

''.

The files detailed the FBI's extensive

COINTELPRO

COINTELPRO ( syllabic abbreviation derived from Counter Intelligence Program; 1956–1971) was a series of covert and illegal projects actively conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrati ...

program, which included investigations into lives of ordinary citizens—including a black student group at a Pennsylvania military college and the daughter of Congressman

Henry S. Reuss

Henry Schoellkopf Reuss (February 22, 1912 – January 12, 2002) was a Democratic U.S. Representative from Wisconsin.

Early life

Henry Schoellkopf Reuss was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He was the son of Gustav A. Reuss (pronounced ''Royce'' ...

of

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

.

The country was "jolted" by the revelations, which included assassinations of political activists, and the actions were denounced by members of the Congress, including House Majority Leader

Hale Boggs

Thomas Hale Boggs Sr. (February 15, 1914 – disappeared October 16, 1972; declared dead December 29, 1972) was an American Democratic politician and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Orleans, Louisiana. He was the House ma ...

.

The phones of some members of the Congress, including Boggs, had allegedly been tapped.

Kennedy's assassination

When President

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

was shot and killed, the jurisdiction fell to the local police departments until President

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

directed the FBI to take over the investigation.

To ensure clarity about the responsibility for investigation of homicides of federal officials, the Congress passed a law that included investigations of such deaths of federal officials, especially by homicide, within FBI jurisdiction. This new law was passed in 1965.

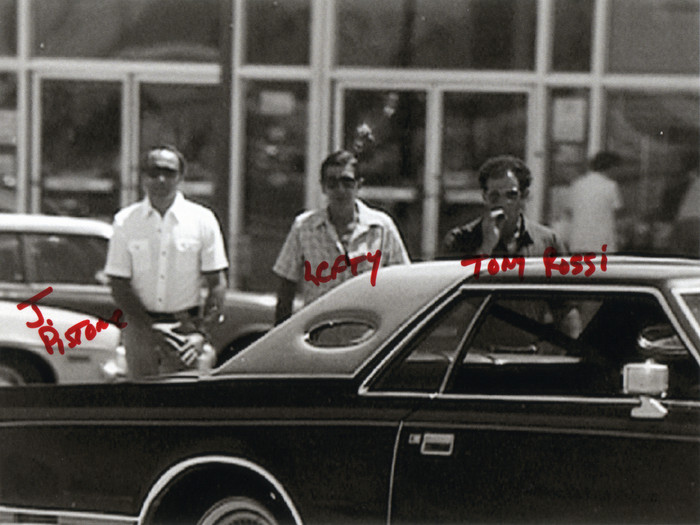

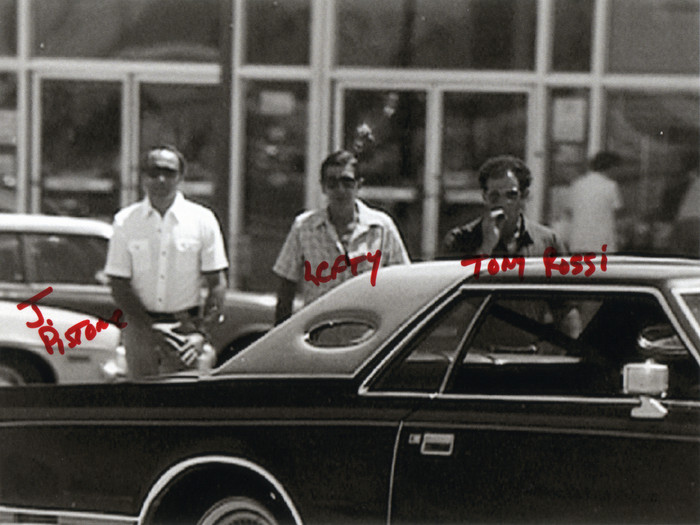

Organized crime

In response to organized crime, on August 25, 1953, the FBI created the Top Hoodlum Program. The national office directed field offices to gather information on mobsters in their territories and to report it regularly to Washington for a centralized collection of intelligence on racketeers. After the

Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act is a United States federal law that provides for extended criminal penalties and a civil cause of action for acts performed as part of an ongoing criminal organization.

RICO was en ...

, or RICO Act, took effect, the FBI began investigating the former Prohibition-organized groups, which had become fronts for crime in major cities and small towns. All of the FBI work was done undercover and from within these organizations, using the provisions provided in the RICO Act. Gradually the agency dismantled many of the groups. Although Hoover initially denied the existence of a

National Crime Syndicate

The National Crime Syndicate was the name given by the press to the multi-ethnic, loosely connected, American confederation of several criminal organizations. It mostly consisted of and was led by the closely interconnected Italian-American Mafia ...

in the United States, the Bureau later conducted operations against known organized crime syndicates and families, including those headed by

Sam Giancana

Salvatore Mooney Giancana (; born Gilormo Giangana; ; May 24, 1908 – June 19, 1975) was an American mobster who was boss of the Chicago Outfit from 1957 to 1966.

Giancana was born in Chicago to Italian immigrant parents. He joined the 42 ...

and

John Gotti

John Joseph Gotti Jr.Capeci, Mustain (1996), pp. 25–26 (, ; October 27, 1940 – June 10, 2002) was an American gangster and boss of the Gambino crime family in New York City. He ordered and helped to orchestrate the murder of Gambino boss ...

. The RICO Act is still used today for all

organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally th ...

and any individuals who may fall under the Act's provisions.

In 2003, a congressional committee called the FBI's organized crime

informant

An informant (also called an informer or, as a slang term, a “snitch”) is a person who provides privileged information about a person or organization to an agency. The term is usually used within the law-enforcement world, where informan ...

program "one of the greatest failures in the history of federal law enforcement."

The FBI allowed four innocent men to be convicted of the

March 1965 gangland murder of Edward "Teddy" Deegan in order to protect

Vincent Flemmi

Vincent James Flemmi (September 5, 1935 – October 16, 1979), also known as "Jimmy The Bear", was an American mobster who freelanced for the Winter Hill Gang and the Patriarca crime family. He was also a longtime informant for the Federal Bureau ...

, an FBI informant. Three of the men were sentenced to death (which was later reduced to life in prison), and the fourth defendant was sentenced to life in prison.

Two of the four men died in prison after serving almost 30 years, and two others were released after serving 32 and 36 years. In July 2007, U.S. District Judge

Nancy Gertner

Nancy Gertner (born May 22, 1946) is a former United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts. She assumed senior status on May 22, 2011, and retired outright from the federal bench on September ...

in Boston found that the Bureau had helped convict the four men using false witness accounts given by mobster

Joseph Barboza

Joseph Barboza Jr. (; September 20, 1932 – February 11, 1976), nicknamed "the Animal", was an American mobster and notorious mob hitman for the Patriarca crime family of New England during the 1960s. A prominent enforcer and contract killer in ...

. The U.S. Government was ordered to pay $100 million in damages to the four defendants.

Special FBI teams

In 1982, the FBI formed an elite unit

to help with problems that might arise at the

1984 Summer Olympics

The 1984 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXIII Olympiad and also known as Los Angeles 1984) were an international multi-sport event held from July 28 to August 12, 1984, in Los Angeles, California, United States. It marked the secon ...

to be held in Los Angeles, particularly

terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

and major-crime. This was a result of the

1972 Summer Olympics

The 1972 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the XX Olympiad () and commonly known as Munich 1972 (german: München 1972), was an international multi-sport event held in Munich, West Germany, from 26 August to 11 September 1972. ...

in

Munich, Germany

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

, when

terrorists murdered the Israeli athletes. Named the

Hostage Rescue Team

The Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) is the elite tactical unit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The HRT was formed to provide a full-time federal law enforcement tactical capability to respond to major terrorist incidents throughout the ...

, or HRT, it acts as a dedicated FBI

SWAT

In the United States, a SWAT team (special weapons and tactics, originally special weapons assault team) is a police tactical unit that uses specialized or military equipment and tactics. Although they were first created in the 1960s to ...

team dealing primarily with counter-terrorism scenarios. Unlike the special agents serving on local

FBI SWAT

FBI Special Weapons and Tactics Teams are specialized part-time police tactical units (SWAT) of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The FBI maintains SWAT teams at each of its 56 field offices throughout the United States. Each team is co ...

teams, HRT does not conduct investigations. Instead, HRT focuses solely on additional tactical proficiency and capabilities. Also formed in 1984 was the ''Computer Analysis and Response Team'', or CART.

From the end of the 1980s to the early 1990s, the FBI reassigned more than 300 agents from foreign counter-intelligence duties to violent crime, and made violent crime the sixth national priority. With cuts to other well-established departments, and because terrorism was no longer considered a threat after the end of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

,

the FBI assisted local and state police forces in tracking fugitives who had crossed state lines, which is a federal offense. The FBI Laboratory helped develop

DNA testing, continuing its pioneering role in identification that began with its fingerprinting system in 1924.

Notable efforts in the 1990s

On May 1, 1992, FBI SWAT and HRT personnel in

Los Angeles County, California

Los Angeles County, officially the County of Los Angeles, and sometimes abbreviated as L.A. County, is the List of the most populous counties in the United States, most populous county in the United States and in the U.S. state of California, ...

aided local officials in securing peace within the area during the

1992 Los Angeles riots

The 1992 Los Angeles riots, sometimes called the 1992 Los Angeles uprising and the Los Angeles Race Riots, were a series of riots and civil disturbances that occurred in Los Angeles County, California, in April and May 1992. Unrest began in S ...

. HRT operators, for instance, spent 10 days conducting vehicle-mounted patrols throughout

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

, before returning to Virginia.

Between 1993 and 1996, the FBI increased its

counter-terrorism

Counterterrorism (also spelled counter-terrorism), also known as anti-terrorism, incorporates the practices, military tactics, techniques, and strategies that governments, law enforcement, business, and intelligence agencies use to combat or el ...

role following the first

1993 World Trade Center bombing

The 1993 World Trade Center bombing was a terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York City, U.S., carried out on February 26, 1993, when a van bomb detonated below the North Tower of the complex. The urea nitrate–hydrogen gas en ...

in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, the 1995

Oklahoma City bombing

The Oklahoma City bombing was a domestic terrorist truck bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, United States, on April 19, 1995. Perpetrated by two anti-government extremists, Timothy McVeigh and Terry N ...

, and the arrest of the

Unabomber

Theodore John Kaczynski ( ; born May 22, 1942), also known as the Unabomber (), is an American domestic terrorist and former mathematics professor. Between 1978 and 1995, Kaczynski killed three people and injured 23 others in a nationwide ...

in 1996. Technological innovation and the skills of FBI Laboratory analysts helped ensure that the three cases were successfully prosecuted.

However, Justice Department investigations into the FBI's roles in the

Ruby Ridge

Ruby Ridge was the site of an eleven-day siege in 1992 in Boundary County, Idaho, near Naples. It began on August 21, when deputies of the United States Marshals Service (USMS) initiated action to apprehend and arrest Randy Weaver under a bench ...

and

Waco

Waco ( ) is the county seat of McLennan County, Texas, United States. It is situated along the Brazos River and I-35, halfway between Dallas and Austin. The city had a 2020 population of 138,486, making it the 22nd-most populous city in the st ...

incidents were found to have been obstructed by agents within the Bureau. During the

1996 Summer Olympics

The 1996 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXVI Olympiad, also known as Atlanta 1996 and commonly referred to as the Centennial Olympic Games) were an international multi-sport event held from July 19 to August 4, 1996, in Atlanta, ...

in

Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, the FBI was criticized for its investigation of the

Centennial Olympic Park bombing

The Centennial Olympic Park bombing was a domestic terrorist pipe bombing attack on Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, on July 27, 1996, during the 1996 Summer Olympics, Summer Olympics. The blast directly killed ...

. It has settled a dispute with

Richard Jewell

Richard Allensworth Jewell (born Richard White; December 17, 1962 – August 29, 2007) was an American security guard and law enforcement officer who alerted police during the Centennial Olympic Park bombing at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlant ...

, who was a private security guard at the venue, along with some media organizations,

in regard to the leaking of his name during the investigation; this had briefly led to his being wrongly suspected of the bombing.

After Congress passed the

Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act

The Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA), also known as the "Digital Telephony Act," is a United States wiretapping law passed in 1994, during the presidency of Bill Clinton (Pub. L. No. 103-414, 108 Stat. 4279, codified at 47 ...

(CALEA, 1994), the

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA or the Kennedy– Kassebaum Act) is a United States Act of Congress enacted by the 104th United States Congress and signed into law by President Bill Clinton on August 21, 1 ...

(HIPAA, 1996), and the

Economic Espionage Act

The Economic Espionage Act of 1996 () was a 6 title Act of Congress dealing with a wide range of issues, including not only industrial espionage (''e.g.'', the theft or misappropriation of a trade secret and the National Information Infrastructu ...

(EEA, 1996), the FBI followed suit and underwent a technological upgrade in 1998, just as it did with its CART team in 1991. Computer Investigations and Infrastructure Threat Assessment Center (CITAC) and the National Infrastructure Protection Center (NIPC) were created to deal with the increase in

Internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, pub ...

-related problems, such as computer viruses, worms, and other malicious programs that threatened U.S. operations. With these developments, the FBI increased its electronic surveillance in public safety and national security investigations, adapting to the telecommunications advancements that changed the nature of such problems.

September 11 attacks

During the

September 11, 2001, attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerc ...

on the

World Trade Center

World Trade Centers are sites recognized by the World Trade Centers Association.

World Trade Center may refer to:

Buildings

* List of World Trade Centers

* World Trade Center (2001–present), a building complex that includes five skyscrapers, a ...

, FBI agent

Leonard W. Hatton Jr.

Leonard William Hatton Jr. (August 17, 1956 – September 11, 2001) was an American special agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was killed in the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City when he enter ...

was killed during the rescue effort while helping the rescue personnel evacuate the occupants of the South Tower, and he stayed when it collapsed. Within months after the attacks, FBI Director

Robert Mueller

Robert Swan Mueller III (; born August 7, 1944) is an American lawyer and government official who served as the sixth director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 2001 to 2013.

A graduate of Princeton University and New York ...

, who had been sworn in a week before the attacks, called for a re-engineering of FBI structure and operations. He made countering every federal crime a top priority, including the prevention of terrorism, countering foreign intelligence operations, addressing cybersecurity threats, other high-tech crimes, protecting civil rights, combating public corruption, organized crime, white-collar crime, and major acts of violent crime.

In February 2001,

Robert Hanssen

Robert Philip Hanssen (born April 18, 1944) is an American former Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) double agent who spied for Soviet and Russian intelligence services against the United States from 1979 to 2001. His espionage was described ...

was caught selling information to the Russian government. It was later learned that Hanssen, who had reached a high position within the FBI, had been selling intelligence since as early as 1979. He pleaded guilty to

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

and received a

life sentence

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted people are to remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives or indefinitely until pardoned, paroled, or otherwise commuted to a fixed term. Crimes for ...

in 2002, but the incident led many to question the security practices employed by the FBI. There was also a claim that Hanssen might have contributed information that led to the September 11, 2001, attacks.

The

9/11 Commission

The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, also known as the 9/11 Commission, was set up on November 27, 2002, "to prepare a full and complete account of the circumstances surrounding the September 11 attacks", includin ...

's final report on July 22, 2004, stated that the FBI and

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) were both partially to blame for not pursuing intelligence reports that could have prevented the September 11 attacks. In its most damning assessment, the report concluded that the country had "not been well served" by either agency and listed numerous recommendations for changes within the FBI.

While the FBI did accede to most of the recommendations, including oversight by the new

Director of National Intelligence

The director of national intelligence (DNI) is a senior, cabinet-level United States government official, required by the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 to serve as executive head of the United States Intelligence Commu ...

, some former members of the 9/11 Commission publicly criticized the FBI in October 2005, claiming it was resisting any meaningful changes.

On July 8, 2007, ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' published excerpts from

UCLA

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California St ...

Professor Amy Zegart's book ''Spying Blind: The CIA, the FBI, and the Origins of 9/11''.

The ''Post'' reported, from Zegart's book, that government documents showed that both the CIA and the FBI had missed 23 potential chances to disrupt the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The primary reasons for the failures included: agency cultures resistant to change and new ideas; inappropriate incentives for promotion; and a lack of cooperation between the FBI, CIA, and the rest of the

United States Intelligence Community

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

. The book blamed the FBI's decentralized structure, which prevented effective communication and cooperation among different FBI offices. The book suggested that the FBI had not evolved into an effective counter-terrorism or counter-intelligence agency, due in large part to deeply ingrained agency cultural resistance to change. For example, FBI personnel practices continued to treat all staff other than special agents as support staff, classifying

intelligence analysts

Intelligence analysis is the application of individual and collective cognitive methods to weigh data and test hypotheses within a secret socio-cultural context. The descriptions are drawn from what may only be available in the form of deliberate ...

alongside the FBI's auto mechanics and janitors.

Faulty bullet analysis

For over 40 years, the FBI crime lab in Quantico had believed that lead alloys used in bullets had unique chemical signatures. It was analyzing the bullets with the goal of matching them chemically, not only to a single batch of ammunition coming out of a factory, but also to a single box of bullets. The

National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

conducted an 18-month independent review of

comparative bullet-lead analysis

Comparative bullet-lead analysis (CBLA), also known as compositional bullet-lead analysis, is a now discredited and abandoned forensic technique which used chemistry to link crime scene bullets to ones possessed by suspects on the theory that each ...

. In 2003, its National Research Council published a report whose conclusions called into question 30 years of FBI testimony. It found the analytic model used by the FBI for interpreting results was deeply flawed, and the conclusion, that bullet fragments could be matched to a box of ammunition, was so overstated that it was misleading under the rules of evidence. One year later, the FBI decided to stop conducting bullet lead analyses.

After a ''

60 Minutes

''60 Minutes'' is an American television news magazine broadcast on the CBS television network. Debuting in 1968, the program was created by Don Hewitt and Bill Leonard, who chose to set it apart from other news programs by using a unique styl ...

''/''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' investigation in November 2007, two years later, the Bureau agreed to identify, review, and release all pertinent cases, and notify prosecutors about cases in which faulty testimony was given.

Technology

In 2012, the FBI formed the

National Domestic Communications Assistance Center The National Domestic Communications Assistance Center (NDCAC) is a National center, formed by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of th ...

to develop technology for assisting law enforcement with technical knowledge regarding communication services, technologies, and electronic surveillance.

Organization

Organizational structure

The FBI is organized into functional branches and the Office of the Director, which contains most administrative offices. An executive assistant director manages each branch. Each branch is then divided into offices and divisions, each headed by an assistant director. The various divisions are further divided into sub-branches, led by deputy assistant directors. Within these sub-branches, there are various sections headed by section chiefs. Section chiefs are ranked analogous to special agents in charge. Four of the branches report to the deputy director while two report to the associate director.

The main branches of the FBI are:

*

FBI Intelligence Branch

The Intelligence Branch (IB) division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) handles all intelligence functions, including information sharing policies and intelligence analysis for national security, homeland security, and law enforcemen ...

**Executive Assistant Director: Stephen Laycock

*

FBI National Security Branch

The National Security Branch (NSB) is a service within the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The NSB is responsible for protecting the United States from weapons of mass destruction, acts of terrorism, and foreign intelligence operations and e ...

**Executive Assistant Director: John Brown

*

FBI Criminal, Cyber, Response, and Services Branch

The Criminal, Cyber, Response, and Services Branch (CCRSB) is a service within the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The CCRSB is responsible for investigating financial crime, white-collar crime, violent crime, organized crime, public corru ...

**Executive Assistant Director: Terry Wade

*

FBI Science and Technology Branch

The Science and Technology Branch (STB) is service within the Federal Bureau of Investigation that comprises three separate divisions and three program offices. The goal when it was founded in July 2006 was to centralize the leadership and manage ...

**Executive Assistant Director: Darrin E. Jones

*

FBI Information and Technology Branch

The Information and Technology Branch (ITB) is a service within the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The ITB is responsible for all FBI information technology needs and information management. ITB also promotes and facilitates the creation, shari ...

**Executive Assistant Director: Michael Gavin (Acting)

*

FBI Human Resources Branch

The Human Resources Branch (HRB) is a service within the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The HRB is responsible for all internal human resources needs of the FBI and for conducting the FBI Academy to train new FBI agents.

Leadership

Headed by ...

**Executive Assistant Director: Jeffrey S. Sallet

Each branch focuses on different tasks, and some focus on more than one. Here are some of the tasks that different branches are in charge of:

FBI Headquarters Washington D.C.

National Security Branch (NSB)

*

Counterintelligence Division (CD)

*

Counterterrorism Division (CTD)

*

Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate (WMDD)

*

High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group (HIG)

*

Terrorist Screening Center (TSC)

Intelligence Branch (IB)

*

Directorate of Intelligence (DI)

* Office of Partner Engagement (OPE)

* Office of Private Sector

FBI Criminal, Cyber, Response, and Services Branch (CCRSB)

*

Criminal Investigation Division (CID)

*

Cyber Division (CyD)

*

Critical Incident Response Group (CIRG)

* International Operation Division (IOD)

* Victim Services Division

Science and Technology Branch (STB)

* Operational Technology Division (OTD)

*

Laboratory Division (LD)

*

Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIA) Division

Other Headquarter Offices

Information and Technology Branch (ITB)

* IT Enterprise Services Division (ITESD)

* IT Applications and Data Division (ITADD)

*

IT Infrastructure Division (ITID)

*

IT Management Division

*

IT Engineering Division

*

IT Services Division

Human Resources Branch (HRB)

* Training Division (TD)

* Human Resources Division (HRD)

* Security Division (SecD)

Administrative and financial management support

* Facilities and Logistics Services Division (FLSD)

* Finance Division (FD)

* Records Management Division (RMD)

* Resource Planning Office (RPO)

* Inspection Division (InSD)

Office of the Director

The Office of the Director serves as the central administrative organ of the FBI. The office provides staff support functions (such as finance and facilities management) to the five function branches and the various field divisions. The office is managed by the FBI associate director, who also oversees the operations of both the Information and Technology and Human Resources Branches.

Senior staff

* Deputy director

* Associate deputy director

* Chief of staff

Office of the Director

* Finance and Facilities Division

* Information Management Division

* Insider Threat Office

* Inspection Division

* Office of the Chief Information Officer

* Office of Congressional Affairs (OCA)

* Office of Diversity and Inclusion

* Office of Equal Employment Opportunity Affairs (OEEOA)

* Office of the General Counsel (OGC)

* Office of Integrity and Compliance (OIC)

* Office of Internal Auditing

*

Office of the Ombudsman

An ombudsman (, also ,), ombud, ombuds, ombudswoman, ombudsperson or public advocate is an official who is usually appointed by the government or by parliament (usually with a significant degree of independence) to investigate complaints and at ...

* Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR)

* Office of Public Affairs (OPA)

* Resource Planning Office

Rank structure

The following is a listing of the rank structure found within the FBI (in ascending order):

* Field agents

** New agent trainee

**

Special agent

** Senior special agent

** Supervisory special agent

** Assistant special agent-in-charge (ASAC)

** Special agent-in-charge (SAC)

* FBI management

** Deputy assistant director

** Assistant director

** Associate executive assistant director

** Executive assistant director

** Associate deputy director

** Deputy chief of staff

** Chief of staff and special counsel to the director

**

Deputy director

**

Director

Director may refer to:

Literature

* ''Director'' (magazine), a British magazine

* ''The Director'' (novel), a 1971 novel by Henry Denker

* ''The Director'' (play), a 2000 play by Nancy Hasty

Music

* Director (band), an Irish rock band

* ''Di ...

Legal authority

The FBI's mandate is established in

Title 28 of the United States Code

Title 28 (Judiciary and Judicial Procedure) is the portion of the United States Code (federal statutory law) that governs the federal judicial system.

It is divided into six parts:

* Part I: Organization of Courts

* Part II: Department of Jus ...

(U.S. Code), Section 533, which authorizes the

Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

to "appoint officials to detect and prosecute crimes against the United States."

Other federal statutes give the FBI the authority and responsibility to investigate specific crimes.

The FBI's chief tool against

organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally th ...

is the

Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act is a United States federal law that provides for extended criminal penalties and a civil cause of action for acts performed as part of an ongoing criminal organization.

RICO was en ...

(RICO) Act. The FBI is also charged with the responsibility of enforcing compliance of the United States

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

and investigating violations of the act in addition to prosecuting such violations with the

United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United State ...

(DOJ). The FBI also shares concurrent jurisdiction with the

Drug Enforcement Administration

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA; ) is a Federal law enforcement in the United States, United States federal law enforcement agency under the U.S. Department of Justice tasked with combating drug trafficking and distribution within th ...

(DEA) in the enforcement of the

Controlled Substances Act

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) is the statute establishing federal government of the United States, federal drug policy of the United States, U.S. drug policy under which the manufacture, importation, possession, use, and distribution of ...

of 1970.

The

USA PATRIOT Act

The USA PATRIOT Act (commonly known as the Patriot Act) was a landmark Act of Congress, Act of the United States Congress, signed into law by President of the United States, President George W. Bush. The formal name of the statute is the Uniti ...

increased the powers allotted to the FBI, especially in

wiretapping

Telephone tapping (also wire tapping or wiretapping in American English) is the monitoring of telephone and Internet-based conversations by a third party, often by covert means. The wire tap received its name because, historically, the monitorin ...

and monitoring of Internet activity. One of the most controversial provisions of the act is the so-called ''

sneak and peek'' provision, granting the FBI powers to search a house while the residents are away, and not requiring them to notify the residents for several weeks afterward. Under the PATRIOT Act's provisions, the FBI also resumed inquiring into the

library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

records

of those who are suspected of

terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

(something it had supposedly not done since the 1970s).

In the early 1980s, Senate hearings were held to examine FBI undercover operations in the wake of the

Abscam

Abscam (sometimes written ABSCAM) was an FBI sting operation in the late 1970s and early 1980s that led to the convictions of seven members of the United States Congress, among others, for bribery and corruption. The two-year investigation initi ...

controversy, which had allegations of

entrapment

Entrapment is a practice in which a law enforcement agent or agent of the state induces a person to commit a "crime" that the person would have otherwise been unlikely or unwilling to commit.''Sloane'' (1990) 49 A Crim R 270. See also agent provo ...

of elected officials. As a result, in the following years a number of guidelines were issued to constrain FBI activities.

A March 2007 report by the inspector general of the Justice Department described the FBI's "widespread and serious misuse" of

national security letter

A national security letter (NSL) is an administrative subpoena issued by the United States government to gather information for national security purposes. NSLs do not require prior approval from a judge. The Stored Communications Act, Fair Cred ...

s, a form of

administrative subpoena

An administrative subpoena under U.S. law is a subpoena issued by a federal agency without prior judicial oversight. Critics say that administrative subpoena authority is a violation of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, whil ...

used to demand records and data pertaining to individuals. The report said that between 2003 and 2005, the FBI had issued more than 140,000 national security letters, many involving people with no obvious connections to terrorism.

Information obtained through an FBI investigation is presented to the appropriate

U.S. Attorney

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal c ...

or Department of Justice official, who decides if prosecution or other action is warranted.

The FBI often works in conjunction with other federal agencies, including the

U.S. Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, multi ...

(USCG) and

U.S. Customs and Border Protection

United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is the largest federal law enforcement agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security. It is the country's primary border control organization, charged with regulating and facilit ...

(CBP) in seaport and airport security,

and the

National Transportation Safety Board

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is an independent U.S. government investigative agency responsible for civil transportation accident investigation. In this role, the NTSB investigates and reports on aviation accidents and incid ...

in investigating

airplane crashes and other critical incidents.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement

The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is a federal law enforcement agency under the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. ICE's stated mission is to protect the United States from the cross-border crime and illegal immigration tha ...

's Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) has nearly the same amount of investigative manpower as the FBI and investigates the largest range of crimes. In the wake of the

September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercia ...

, then–Attorney General Ashcroft assigned the FBI as the designated lead organization in terrorism investigations after the creation of the

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

The United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is the U.S. federal executive department responsible for public security, roughly comparable to the interior or home ministries of other countries. Its stated missions involve anti-terr ...

. HSI and the FBI are both integral members of the