European starling on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

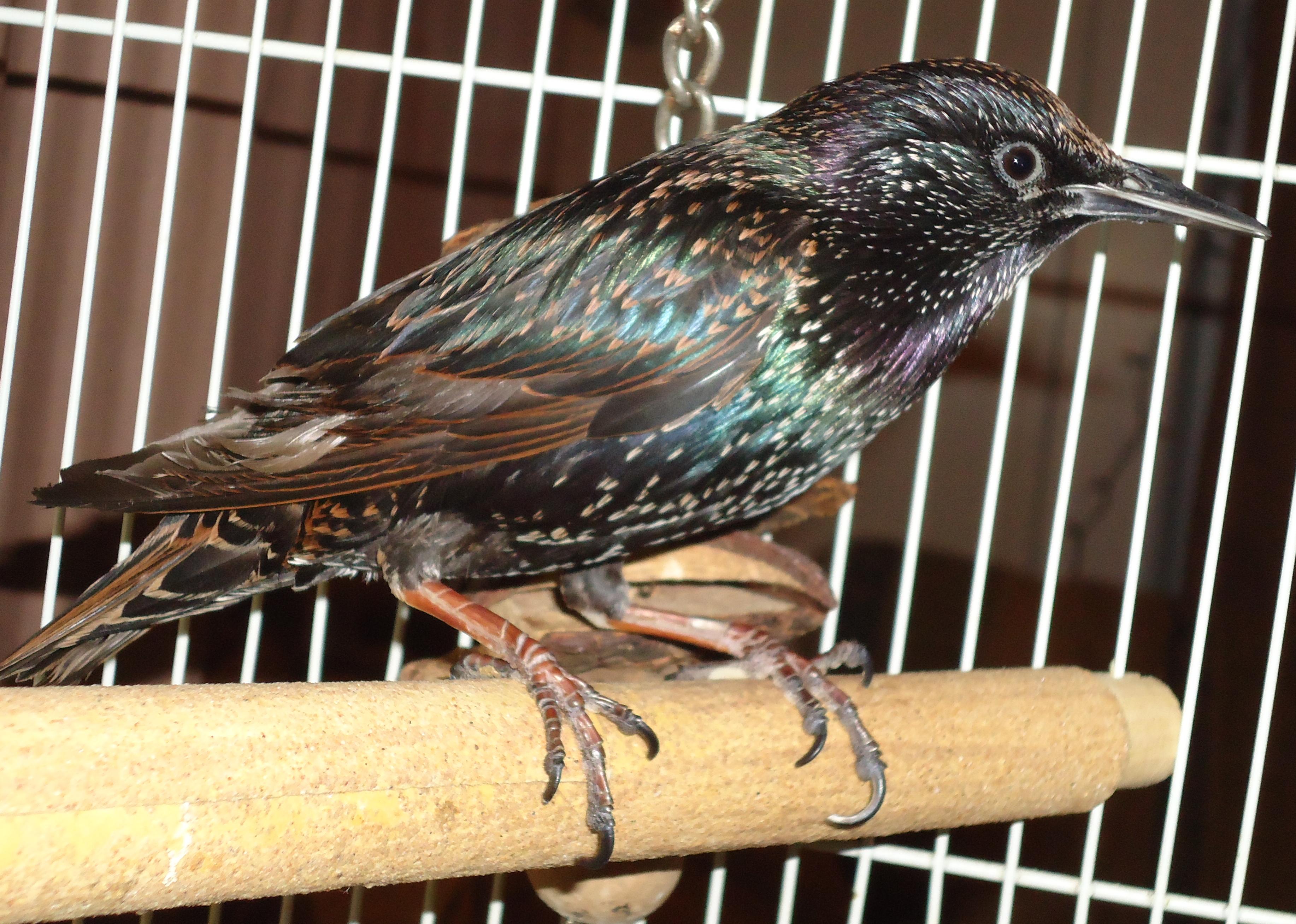

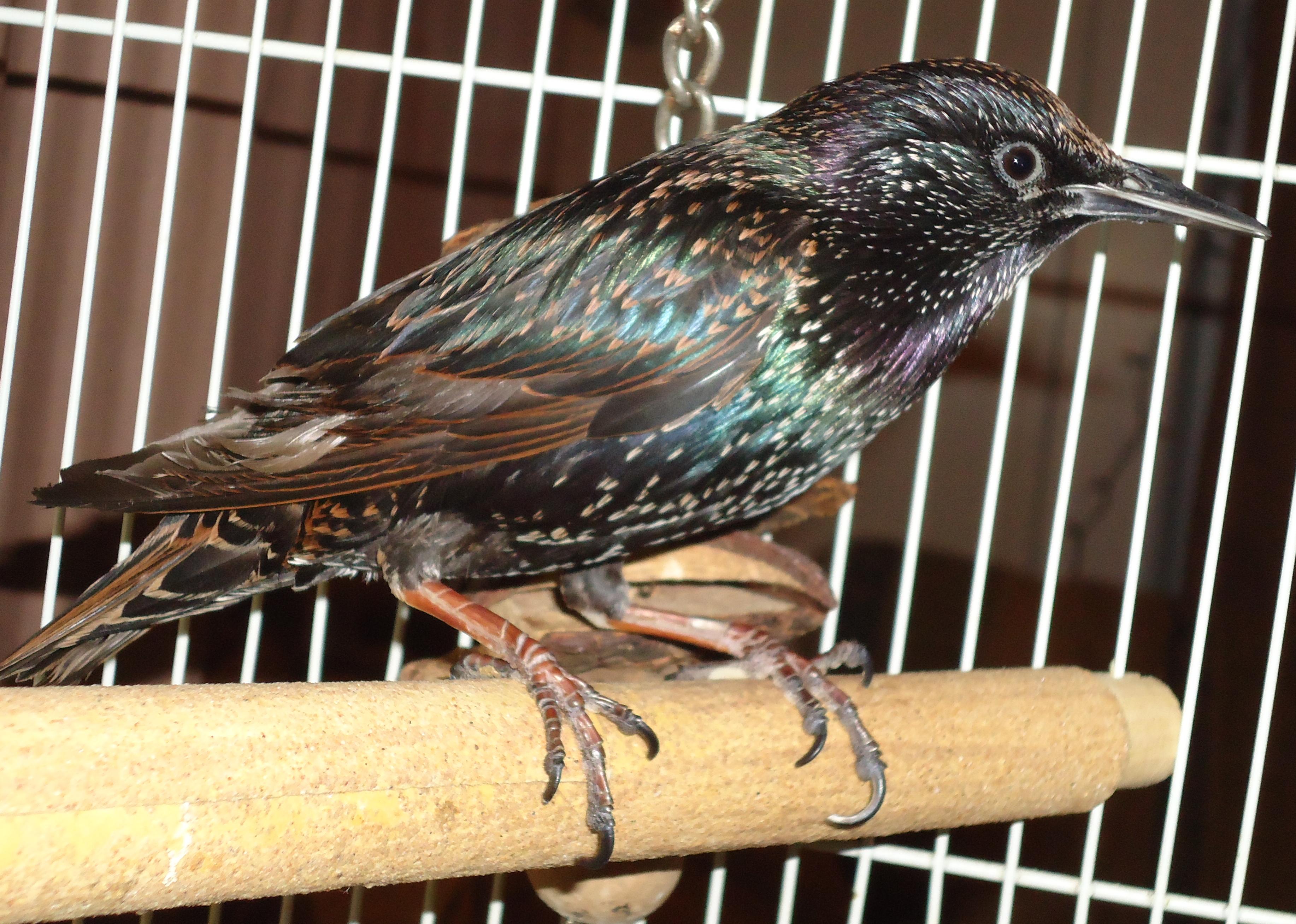

The common starling or European starling (''Sturnus vulgaris''), also known simply as the starling in Great Britain and Ireland, is a medium-sized

SturnusPorphyronotusSmit.jpg, alt=Subspecies ''porphyronotus'', ''S. v. porphyronotus''

Ab bird 025.jpg, alt=Subspecies ''tauricus'', ''S. v. tauricus'' in

Birds from

The common starling is long, with a wingspan of and a weight of . Among standard measurements, the wing chord is , the

The common starling is long, with a wingspan of and a weight of . Among standard measurements, the wing chord is , the  Like most terrestrial starlings the common starling moves by walking or running, rather than hopping. Their flight is quite strong and direct; their triangular wings beat very rapidly, and periodically the birds glide for a short way without losing much height before resuming powered flight. When in a flock, the birds take off almost simultaneously, wheel and turn in unison, form a compact mass or trail off into a wispy stream, bunch up again and land in a coordinated fashion. Common starling on migration can fly at and cover up to .

Several terrestrial starlings, including those in the

Like most terrestrial starlings the common starling moves by walking or running, rather than hopping. Their flight is quite strong and direct; their triangular wings beat very rapidly, and periodically the birds glide for a short way without losing much height before resuming powered flight. When in a flock, the birds take off almost simultaneously, wheel and turn in unison, form a compact mass or trail off into a wispy stream, bunch up again and land in a coordinated fashion. Common starling on migration can fly at and cover up to .

Several terrestrial starlings, including those in the

The common starling is a noisy bird. Its

The common starling is a noisy bird. Its

The common starling is largely

The common starling is largely

Breeding takes place during the spring and summer. Following copulation, the female lays eggs on a daily basis over a period of several days. If an egg is lost during this time, she will lay another to replace it. There are normally four or five eggs that are

Breeding takes place during the spring and summer. Following copulation, the female lays eggs on a daily basis over a period of several days. If an egg is lost during this time, she will lay another to replace it. There are normally four or five eggs that are

The hen flea ('' Ceratophyllus gallinae'') is the most common

The hen flea ('' Ceratophyllus gallinae'') is the most common

1960

. The hen mite ''D. gallinae'' is itself preyed upon by the predatory mite '' Androlaelaps casalis''. The presence of this control on numbers of the parasitic species may explain why birds are prepared to reuse old nests.Lesna, I; Wolfs, P; Faraji, F; Roy, L; Komdeur, J; Sabelis, M W. "Candidate predators for biological control of the poultry red mite ''Dermanyssus gallinae''" in Sparagano (2009) pp. 75–76. Flying insects that parasitise common starlings include the louse-fly ''Omithomya nigricornis'' and the

Common starlings in the south and west of Europe and south of latitude 40°N are mainly resident, although other populations migrate from regions where the winter is harsh, the ground frozen and food scarce. Large numbers of birds from northern Europe, Russia and Ukraine migrate south westwards or south eastwards. In the autumn, when immigrants are arriving from eastern Europe, many of Britain's common starlings are setting off for

Common starlings in the south and west of Europe and south of latitude 40°N are mainly resident, although other populations migrate from regions where the winter is harsh, the ground frozen and food scarce. Large numbers of birds from northern Europe, Russia and Ukraine migrate south westwards or south eastwards. In the autumn, when immigrants are arriving from eastern Europe, many of Britain's common starlings are setting off for

Various

Various

Since common starlings eat insect pests such as wireworms, they are considered beneficial in northern Eurasia, and this was one of the reasons given for introducing the birds elsewhere. Around 25 million nest boxes were erected for this species in the former

Since common starlings eat insect pests such as wireworms, they are considered beneficial in northern Eurasia, and this was one of the reasons given for introducing the birds elsewhere. Around 25 million nest boxes were erected for this species in the former

Where it is introduced, the common starling is unprotected by legislation, and extensive control plans may be initiated. Common starlings can be prevented from using nest boxes by ensuring that the access holes are smaller than the diameter they need, and the removal of perches discourages them from visiting bird feeders.

Western Australia banned the import of common starlings in 1895. New flocks arriving from the east are routinely shot, while the less cautious juveniles are trapped and netted. New methods are being developed, such as tagging one bird and tracking it back to establish where other members of the flock roost. Another technique is to analyse the DNA of Australian common starling populations to track where the migration from eastern to western Australia is occurring so that better preventive strategies can be used. By 2009, only 300 common starlings were left in Western Australia, and the state committed a further A$400,000 in that year to continue the eradication programme.

In the United States, common starlings are exempt from the

Where it is introduced, the common starling is unprotected by legislation, and extensive control plans may be initiated. Common starlings can be prevented from using nest boxes by ensuring that the access holes are smaller than the diameter they need, and the removal of perches discourages them from visiting bird feeders.

Western Australia banned the import of common starlings in 1895. New flocks arriving from the east are routinely shot, while the less cautious juveniles are trapped and netted. New methods are being developed, such as tagging one bird and tracking it back to establish where other members of the flock roost. Another technique is to analyse the DNA of Australian common starling populations to track where the migration from eastern to western Australia is occurring so that better preventive strategies can be used. By 2009, only 300 common starlings were left in Western Australia, and the state committed a further A$400,000 in that year to continue the eradication programme.

In the United States, common starlings are exempt from the

Common starlings may be kept as pets or as laboratory animals. Austrian

Common starlings may be kept as pets or as laboratory animals. Austrian

Very noisy Starling flocks in ScotlandAgeing and sexing (PDF; 4.7 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael HeinzeKalmbach, E R; Gabrielson, I N (1921) "Economic value of the starling in the United States" ''USDA Bulletin 868''

* * *(European) Common starling

Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

Species Profile - European Starling (''Sturnus vulgaris'')

National Invasive Species Information Center,

passerine

A passerine () is any bird of the order Passeriformes (; from Latin 'sparrow' and '-shaped'), which includes more than half of all bird species. Sometimes known as perching birds, passerines are distinguished from other orders of birds by th ...

bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

in the starling family, Sturnidae. It is about long and has glossy black plumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

with a metallic sheen, which is speckled with white at some times of year. The legs are pink and the bill is black in winter and yellow in summer; young birds have browner plumage than the adults. It is a noisy bird, especially in communal roosts and other gregarious situations, with an unmusical but varied song. Its gift for mimicry

In evolutionary biology, mimicry is an evolved resemblance between an organism and another object, often an organism of another species. Mimicry may evolve between different species, or between individuals of the same species. Often, mimicry f ...

has been noted in literature including the ''Mabinogion

The ''Mabinogion'' () are the earliest Welsh prose stories, and belong to the Matter of Britain. The stories were compiled in Middle Welsh in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions. There are two main source manuscripts, creat ...

'' and the works of Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

and William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

.

The common starling has about 12 subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all specie ...

breeding in open habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

s across its native range in temperate Europe and across the Palearctic

The Palearctic or Palaearctic is the largest of the eight biogeographic realms of the Earth. It stretches across all of Eurasia north of the foothills of the Himalayas, and North Africa.

The realm consists of several bioregions: the Euro-Sib ...

to western Mongolia, and it has been introduced to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

and Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consis ...

. This bird is resident in western and southern Europe and southwestern Asia, while northeastern populations migrate south and west in the winter within the breeding range and also further south to Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese language, Aragonese and Occitan language, Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a pe ...

and North Africa. The common starling builds an untidy nest

A nest is a structure built for certain animals to hold eggs or young. Although nests are most closely associated with birds, members of all classes of vertebrates and some invertebrates construct nests. They may be composed of organic materi ...

in a natural or artificial cavity in which four or five glossy, pale blue eggs are laid. These take two weeks to hatch and the young remain in the nest for another three weeks. There are normally one or two breeding attempts each year. This species is omnivorous, taking a wide range of invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s, as well as seeds and fruit. It is hunted by various mammals and birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predat ...

, and is host to a range of external and internal parasites.

Large flocks typical of this species can be beneficial to agriculture by controlling invertebrate pests; however, starlings can also be pests themselves when they feed on fruit and sprouting crops. Common starlings may also be a nuisance through the noise and mess caused by their large urban roosts. Introduced populations in particular have been subjected to a range of controls, including culling

In biology, culling is the process of segregating organisms from a group according to desired or undesired characteristics. In animal breeding, it is the process of removing or segregating animals from a breeding stock based on a specific tr ...

, but these have had limited success, except in preventing the colonisation of Western Australia.

The species has declined in numbers in parts of northern and western Europe since the 1980s due to fewer grassland invertebrates being available as food for growing chicks. Despite this, its huge global population is not thought to be declining significantly, so the common starling is classified as being of least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. ...

by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

.

Taxonomy and systematics

The common starling was first described byCarl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

in his ''Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the system, now known as binomial ...

'' in 1758 under its current binomial name. ''Sturnus'' and ''vulgaris'' are derived from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

for "starling" and "common" respectively.Jobling (2010) pp. 367, 405. The Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

, later , and the Latin are both derived from an unknown Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

root dating back to the second millennium BC. "Starling" was first recorded in the 11th century, when it referred to the juvenile of the species, but by the 16th century it had already largely supplanted "stare" to refer to birds of all ages.Lockwood (1984) p. 147. The older name is referenced in William Butler Yeats' poem "The Stare's Nest by My Window".Yeats (2000) p. 173 The International Ornithological Congress's preferred English vernacular name is common starling.

The starling

Starlings are small to medium-sized passerine birds in the family Sturnidae. The Sturnidae are named for the genus '' Sturnus'', which in turn comes from the Latin word for starling, ''sturnus''. Many Asian species, particularly the larger ones, ...

family, Sturnidae, is an entirely Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

group apart from introductions elsewhere, with the greatest numbers of species in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

and sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

.Feare & Craig (1998) p. 13. The genus ''Sturnus'' is polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage of organisms or other evolving elements that is of mixed evolutionary origin. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as homoplasies, which are explained as a result of conver ...

and relationships between its members are not fully resolved. The closest relation of the common starling is the spotless starling

The spotless starling (''Sturnus unicolor'') is a passerine bird in the starling family, Sturnidae. It is closely related to the common starling (''S. vulgaris''), but has a much more restricted range, confined to the Iberian Peninsula, Northwest ...

. The non-migratory spotless starling may be descended from a population of ancestral ''S. vulgaris'' that survived in an Iberian refugium during an Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

retreat, and mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used ...

l gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

studies suggest that it could be considered a subspecies of the common starling. There is more genetic variation between common starling populations than between the nominate common starling and the spotless starling. Although common starling remains are known from the Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. Th ...

, part of the problem in resolving relationships in the Sturnidae is the paucity of the fossil record for the family as a whole.

Subspecies

There are severalsubspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all specie ...

of the common starling, which vary clinally in size and the colour tone of the adult plumage. The gradual variation over geographic range and extensive intergradation means that acceptance of the various subspecies varies between authorities.

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

Sturnus vulgaris faroensis.jpg, alt=Subspecies ''faroensis'', ''S. v. faroensis'' in the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

An European Starling on the ground.jpg, alt=Subspecies ''vulgaris'', ''S. v. vulgaris'' in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

Fair Isle

Fair Isle (; sco, Fair Isle; non, Friðarey; gd, Fara) is an island in Shetland, in northern Scotland. It lies about halfway between mainland Shetland and Orkney. It is known for its bird observatory and a traditional style of knitting. Th ...

, St. Kilda and the Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coas ...

are intermediate in size between ''S. v. zetlandicus'' and the nominate form, and their subspecies placement varies according to the authority. The dark juveniles typical of these island forms are occasionally found in mainland Scotland and elsewhere, indicating some gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as gene migration or geneflow and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent a ...

from ''faroensis'' or ''zetlandicus'', subspecies formerly considered to be isolated.Neves (2005) pp. 63–73.Parkin & Knox (2009) pp. 65, 305–306.

Several other subspecies have been named, but are generally no longer considered valid. Most are intergrades that occur where the ranges of various subspecies meet. These include: ''S. v. ruthenus'' Menzbier, 1891 and ''S. v. jitkowi'' Buturlin, 1904, which are intergrades between ''vulgaris'' and ''poltaratskyi'' from western Russia; ''S. v. graecus'' Tschusi, 1905 and ''S. v. balcanicus'' Buturlin and Harms, 1909, which are intergrades between ''vulgaris'' and ''tauricus'' from the southern Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

to central Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

and throughout Greece to the Bosporus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

; and ''S. v. heinrichi'' Stresemann Stresemann is a German family name which may refer to:

* Christina Stresemann (born 1957), German judge; daughter of Wolfgang Stresemann

* Erwin Stresemann (1889 – 1972), German ornithologist

* Gustav Stresemann (1878 – 1929), German politician ...

, 1928, an intergrade between ''caucasicus'' and ''nobilior'' in northern Iran. ''S. v. persepolis'' Ticehurst

Ticehurst is both a village and a large civil parish in the Rother district of East Sussex, England. The parish lies in the upper reaches of both the Bewl stream before it enters Bewl Water and in the upper reaches of the River Rother flowi ...

, 1928 from southern Iran's ( Fars Province) is very similar to ''vulgaris'', and it is not clear whether it is a distinct resident population or simply migrants from southeastern Europe.

Description

The common starling is long, with a wingspan of and a weight of . Among standard measurements, the wing chord is , the

The common starling is long, with a wingspan of and a weight of . Among standard measurements, the wing chord is , the tail

The tail is the section at the rear end of certain kinds of animals’ bodies; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage to the torso. It is the part of the body that corresponds roughly to the sacrum and coccyx in mammal ...

is , the culmen is and the tarsus is . The plumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

is iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear to gradually change color as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Examples of iridescence include soap bubbles, feathers, butterfl ...

black, glossed purple or green, and spangled with white, especially in winter. The underparts of adult male common starlings are less spotted than those of adult females at a given time of year. The throat feathers of males are long and loose and are used in display while those of females are smaller and more pointed. The legs are stout and pinkish- or greyish-red. The bill is narrow and conical with a sharp tip; in the winter it is brownish-black but in summer, females have lemon yellow beaks with pink bases while males have yellow bills with blue-grey bases. Moult

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is the manner in which an animal routinely casts off a part of its body (often, but not always, an outer ...

ing occurs once a year- in late summer after the breeding season has finished; the fresh feathers are prominently tipped white (breast feathers) or buff (wing and back feathers), which gives the bird a speckled appearance. The reduction in the spotting in the breeding season is achieved through the white feather tips largely wearing off. Juveniles are grey-brown and by their first winter resemble adults though often retaining some brown juvenile feathering, especially on the head.Snow & Perrins (1998) pp. 1492–1496.Coward (1941) pp. 38–41. They can usually be sexed by the colour of the irises, rich brown in males, mouse-brown or grey in females. Estimating the contrast between an iris and the central always-dark pupil

The pupil is a black hole located in the center of the Iris (anatomy), iris of the Human eye, eye that allows light to strike the retina.Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. (1990) ''Dictionary of Eye Terminology''. Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing ...

is 97% accurate in determining sex, rising to 98% if the length of the throat feathers is also considered. The common starling is mid-sized by both starling standards and passerine standards. It is readily distinguished from other mid-sized passerines, such as thrushes, icterid

Icterids () or New World blackbirds make up a family, the Icteridae (), of small to medium-sized, often colorful, New World passerine birds. Most species have black as a predominant plumage color, often enlivened by yellow, orange, or red. The ...

s or small corvids, by its relatively short tail, sharp, blade-like bill, round-bellied shape and strong, sizeable (and rufous-coloured) legs. In flight, its strongly pointed wings and dark colouration are distinctive, while on the ground its strange, somewhat waddling gait is also characteristic. The colouring and build usually distinguish this bird from other starlings, although the closely related spotless starling

The spotless starling (''Sturnus unicolor'') is a passerine bird in the starling family, Sturnidae. It is closely related to the common starling (''S. vulgaris''), but has a much more restricted range, confined to the Iberian Peninsula, Northwest ...

may be physically distinguished by the lack of iridescent spots in adult breeding plumage.

Like most terrestrial starlings the common starling moves by walking or running, rather than hopping. Their flight is quite strong and direct; their triangular wings beat very rapidly, and periodically the birds glide for a short way without losing much height before resuming powered flight. When in a flock, the birds take off almost simultaneously, wheel and turn in unison, form a compact mass or trail off into a wispy stream, bunch up again and land in a coordinated fashion. Common starling on migration can fly at and cover up to .

Several terrestrial starlings, including those in the

Like most terrestrial starlings the common starling moves by walking or running, rather than hopping. Their flight is quite strong and direct; their triangular wings beat very rapidly, and periodically the birds glide for a short way without losing much height before resuming powered flight. When in a flock, the birds take off almost simultaneously, wheel and turn in unison, form a compact mass or trail off into a wispy stream, bunch up again and land in a coordinated fashion. Common starling on migration can fly at and cover up to .

Several terrestrial starlings, including those in the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

'' Sturnus'', have adaptations of the skull and muscles that help with feeding by probing.Feare & Craig (1998) pp. 21–22. This adaptation is most strongly developed in the common starling (along with the spotless and white-cheeked starling

The white-cheeked starling or grey starling (''Spodiopsar cineraceus'') is a passerine bird of the starling family. It is native to eastern Asia where it is a common and well-known bird in much of its range. Usually, it is placed in the genus ''S ...

s), where the protractor muscles responsible for opening the jaw are enlarged and the skull is narrow, allowing the eye to be moved forward to peer down the length of the bill.del Hoyo ''et al'' (2009) pp. 665–667. This technique involves inserting the bill into the ground and opening it as a way of searching for hidden food items. Common starlings have the physical traits that enable them to use this feeding technique, which has undoubtedly helped the species spread far and wide.Feare & Craig (1998) pp. 183–189.

In Iberia, the western Mediterranean and northwest Africa, the common starling may be confused with the closely related spotless starling, the plumage of which, as its name implies, has a more uniform colour. At close range it can be seen that the latter has longer throat feathers, a fact particularly noticeable when it sings.del Hoyo ''et al'' (2009) p. 725.

Vocalization

The common starling is a noisy bird. Its

The common starling is a noisy bird. Its song

A song is a musical composition intended to be performed by the human voice. This is often done at distinct and fixed pitches (melodies) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs contain various forms, such as those including the repetiti ...

consists of a wide variety of both melodic and mechanical-sounding noises as part of a ritual succession of sounds. The male is the main songster and engages in bouts of song lasting for a minute or more. Each of these typically includes four varieties of song type, which follow each other in a regular order without pause. The bout starts with a series of pure-tone whistles and these are followed by the main part of the song, a number of variable sequences that often incorporate snatches of song mimicked from other species of bird and various naturally occurring or man-made noises. The structure and simplicity of the sound mimicked is of greater importance than the frequency with which it occurs. In some instances, a wild starling has been observed to mimic a sound it has heard only once. Each sound clip is repeated several times before the bird moves on to the next. After this variable section comes a number of types of repeated clicks followed by a final burst of high-frequency song, again formed of several types. Each bird has its own repertoire

A repertoire () is a list or set of dramas, operas, musical compositions or roles which a company or person is prepared to perform.

Musicians often have a musical repertoire. The first known use of the word ''repertoire'' was in 1847. It is a ...

with more proficient birds having a range of up to 35 variable song types and as many as 14 types of clicks.

Males sing constantly as the breeding period approaches and perform less often once pairs have bonded. In the presence of a female, a male sometimes flies to his nest and sings from the entrance, apparently attempting to entice the female in. Older birds tend to have a wider repertoire than younger ones. Those males that engage in longer bouts of singing and that have wider repertoires attract mates earlier and have greater reproductive success than others. Females appear to prefer mates with more complex songs, perhaps because this indicates greater experience or longevity. Having a complex song is also useful in defending a territory and deterring less experienced males from encroaching.

Along with having adaptions of the skull and muscles for singing, male starlings also have a much larger syrinx

In classical Greek mythology, Syrinx ( Greek Σύριγξ) was a nymph and a follower of Artemis, known for her chastity. Pursued by the amorous god Pan, she ran to a river's edge and asked for assistance from the river nymphs. In answer, ...

than females. This is due to increased muscle mass and enlarged elements of the syringeal skeleton. The male starling's syrinx is around 35% larger than its female counterpart. However, this sexual dimorphism is less pronounced than it is in songbird species like the zebra finch, where the male's syrinx is 100% larger than the female's syrinx.

Singing also occurs outside the breeding season, taking place throughout the year apart from the moulting period. The songsters are more commonly male although females also sing on occasion. The function of such out-of-season song is poorly understood. Eleven other types of call have been described including a flock call, threat call, attack call, snarl call and copulation call.Higgins ''et al'' (2006) pp. 1923–1928. The alarm call is a harsh scream, and while foraging together common starlings squabble incessantly. They chatter while roosting and bathing, making a great deal of noise that can cause irritation to people living nearby. When a flock of common starlings is flying together, the synchronised movements of the birds' wings make a distinctive whooshing sound that can be heard hundreds of metres away.

Behaviour and ecology

The common starling is a highly gregarious species, especially in autumn and winter. Although flock size is highly variable, huge, noisy flocks - murmurations - may form near roosts. These dense concentrations of birds are thought to be a defence against attacks bybirds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predat ...

such as peregrine falcon

The peregrine falcon (''Falco peregrinus''), also known as the peregrine, and historically as the duck hawk in North America, is a cosmopolitan bird of prey (raptor) in the family Falconidae. A large, crow-sized falcon, it has a blue-grey bac ...

s or Eurasian sparrowhawk

The Eurasian sparrowhawk (''Accipiter nisus''), also known as the northern sparrowhawk or simply the sparrowhawk, is a small bird of prey in the family Accipitridae. Adult male Eurasian sparrowhawks have bluish grey upperparts and orange-barr ...

s.Taylor & Holden (2009) p. 27. Flocks form a tight sphere

A sphere () is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance from a given point in three-dimensional space.. That given point is the c ...

-like formation in flight, frequently expanding and contracting and changing shape, seemingly without any sort of leader. Each common starling changes its course and speed as a result of the movement of its closest neighbours.

Very large roosts, up to 1.5 million birds, form in city centres, woodlands and reedbeds, causing problems with their droppings. These may accumulate up to deep, killing trees by their concentration of chemicals. In smaller amounts, the droppings act as a fertiliser, and therefore woodland managers may try to move roosts from one area of a wood to another to benefit from the soil enhancement and avoid large toxic deposits.Currie ''et al'' (1977) leaflet 69.

Flocks of more than a million common starlings may be observed just before sunset in spring in southwestern Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

, Denmark, over the seaward marshland

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found at ...

s of Tønder

Tønder (; german: Tondern ) is a town in the Region of Southern Denmark. With a population of 7,505 (as of 1 January 2022), it is the main town and the administrative seat of the Tønder Municipality.

History

The first mention of Tønder might ...

and Esbjerg

Esbjerg (, ) is a seaport town and seat of Esbjerg Municipality on the west coast of the Jutland peninsula in southwest Denmark. By road, it is west of Kolding and southwest of Aarhus. With an urban population of 71,698 (1 January 2022) ...

municipalities between Tønder and Ribe. They gather in March until northern Scandinavian birds leave for their breeding ranges by mid-April. Their swarm behaviour

Swarm behaviour, or swarming, is a collective animal behaviour, collective behaviour exhibited by entities, particularly animals, of similar size which aggregate together, perhaps milling about the same spot or perhaps moving ''en masse'' or a ...

creates complex shapes silhouetted against the sky, a phenomenon known locally as ''sort sol

300px, A formation of starlings in the marshlands near Tønder, Denmark">Tønder.html" ;"title="starlings in the marshlands near Tønder">starlings in the marshlands near Tønder, Denmark.

image:Fugle,_%C3%B8rns%C3%B8_073.jpg, 300px, Blick of so ...

'' ("black sun").

Flocks of anything from five to fifty thousand common starlings form in areas of the UK just before sundown during mid-winter. These flocks are commonly called murmurations.

Feeding

The common starling is largely

The common starling is largely insectivorous

A robber fly eating a hoverfly

An insectivore is a carnivorous animal or plant that eats insects. An alternative term is entomophage, which can also refer to the human practice of eating insects.

The first vertebrate insectivores were ...

and feeds on both pest and other arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s. The food range includes spider

Spiders (order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight legs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species ...

s, crane flies, moth

Moths are a paraphyletic group of insects that includes all members of the order Lepidoptera that are not butterflies, with moths making up the vast majority of the order. There are thought to be approximately 160,000 species of moth, many of w ...

s, mayflies, dragonflies

A dragonfly is a flying insect belonging to the infraorder Anisoptera below the order Odonata. About 3,000 extant species of true dragonfly are known. Most are tropical, with fewer species in temperate regions. Loss of wetland habitat threa ...

, damsel flies, grasshopper

Grasshoppers are a group of insects belonging to the suborder Caelifera. They are among what is possibly the most ancient living group of chewing herbivorous insects, dating back to the early Triassic around 250 million years ago.

Grasshopp ...

s, earwig

Earwigs make up the insect order Dermaptera. With about 2,000 species in 12 families, they are one of the smaller insect orders. Earwigs have characteristic cerci, a pair of forcep-like pincers on their abdomen, and membranous wings folde ...

s, lacewing

The insect order Neuroptera, or net-winged insects, includes the lacewings, mantidflies, antlions, and their relatives. The order consists of some 6,000 species. Neuroptera can be grouped together with the Megaloptera and Raphidioptera in the ...

s, caddisflies

The caddisflies, or order Trichoptera, are a group of insects with aquatic larvae and terrestrial adults. There are approximately 14,500 described species, most of which can be divided into the suborders Integripalpia and Annulipalpia on the ...

, flies

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced m ...

, beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

s, sawflies

Sawflies are the insects of the suborder Symphyta within the order Hymenoptera, alongside ants, bees, and wasps. The common name comes from the saw-like appearance of the ovipositor, which the females use to cut into the plants where they lay ...

, bee

Bees are winged insects closely related to wasps and ants, known for their roles in pollination and, in the case of the best-known bee species, the western honey bee, for producing honey. Bees are a monophyletic lineage within the superfami ...

s, wasp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder ...

s and ants. Prey are consumed in both adult and larvae stages of development, and common starlings will also feed on earthworm

An earthworm is a terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. They exhibit a tube-within-a-tube body plan; they are externally segmented with corresponding internal segmentation; and they usually have setae on all segments. T ...

s, snail

A snail is, in loose terms, a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class ...

s, small amphibian

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbo ...

s and lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia altho ...

s. While the consumption of invertebrates

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordat ...

is necessary for successful breeding, common starlings are omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nut ...

and can also eat grains, seeds

A seed is an embryonic plant enclosed in a protective outer covering, along with a food reserve. The formation of the seed is a part of the process of reproduction in seed plants, the spermatophytes, including the gymnosperm and angiosperm ...

, fruits

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in partic ...

, nectar

Nectar is a sugar-rich liquid produced by plants in glands called nectaries or nectarines, either within the flowers with which it attracts pollinating animals, or by extrafloral nectaries, which provide a nutrient source to animal mutualist ...

and food waste

Food loss and waste is food that is not eaten. The causes of food waste or loss are numerous and occur throughout the food system, during production, processing, distribution, retail and food service sales, and consumption. Overall, about o ...

if the opportunity arises. The Sturnidae differ from most birds in that they cannot easily metabolise foods containing high levels of sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refine ...

, although they can cope with other fruits such as grapes and cherries. The isolated Azores subspecies of the common starling eats the eggs of the endangered roseate tern

The roseate tern (''Sterna dougallii'') is a species of tern in the family Laridae. The genus name ''Sterna'' is derived from Old English "stearn", "tern", and the specific ''dougallii'' refers to Scottish physician and collector Dr Peter McDo ...

. Measures are being introduced to reduce common starling populations by culling before the terns return to their breeding colonies in spring.

There are several methods by which common starlings obtain their food, but, for the most part, they forage close to the ground, taking insects from the surface or just underneath. Generally, common starlings prefer foraging amongst short-cropped grasses and eat with grazing animals or perch on their backs, where they will also feed on the mammal's external parasites. Large flocks may engage in a practice known as "roller-feeding", where the birds at the back of the flock continually fly to the front where the feeding opportunities are best. The larger the flock, the nearer individuals are to one another while foraging. Flocks often feed in one place for some time, and return to previous successfully foraged sites.

There are three types of foraging behaviours observed in the common starling. "Probing" involves the bird plunging its beak into the ground randomly and repetitively until an insect has been found, and is often accompanied by bill gaping where the bird opens its beak in the soil to enlarge a hole. This behaviour, first described by Konrad Lorenz

Konrad Zacharias Lorenz (; 7 November 1903 – 27 February 1989) was an Austrian zoologist, ethologist, and ornithologist. He shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Karl von Frisch. He is often regarde ...

and given the German term ''zirkeln'', is also used to create and widen holes in plastic garbage bags. It takes time for young common starlings to perfect this technique, and because of this the diet of young birds will often contain fewer insects. " Hawking" is the capture of flying insects directly from the air, and "lunging" is the less common technique of striking forward to catch a moving invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

on the ground. Earthworms are caught by pulling from soil. Common starlings that have periods without access to food, or have a reduction in the hours of light available for feeding, compensate by increasing their body mass by the deposition of fat.

Nesting

Unpaired males find a suitable cavity and begin to build nests in order to attract single females, often decorating the nest with ornaments such as flowers and fresh green material, which the female later disassembles upon accepting him as a mate. The amount of green material is not important, as long as some is present, but the presence ofherbs

In general use, herbs are a widely distributed and widespread group of plants, excluding vegetables and other plants consumed for macronutrients, with savory or aromatic properties that are used for flavoring and garnishing food, for medicina ...

in the decorative material appears to be significant in attracting a mate. The scent of plants such as yarrow

''Achillea millefolium'', commonly known as yarrow () or common yarrow, is a flowering plant in the family Asteraceae. Other common names include old man's pepper, devil's nettle, sanguinary, milfoil, soldier's woundwort, and thousand seal.

The ...

acts as an olfactory

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells (or odors) are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

In humans, ...

attractant to females.

The males sing throughout much of the construction and even more so when a female approaches his nest. Following copulation

Sexual intercourse (or coitus or copulation) is a sexual activity typically involving the insertion and thrusting of the penis into the vagina for sexual pleasure or reproduction.Sexual intercourse most commonly means penile–vaginal penetra ...

, the male and female continue to build the nest. Nests may be in any type of hole, common locations include inside hollowed trees, buildings, tree stumps and man-made nest-boxes. ''S. v. zetlandicus'' typically breeds in crevices and holes in cliffs, a habitat only rarely used by the nominate form. Nests are typically made out of straw, dry grass and twigs with an inner lining made up of feathers, wool and soft leaves. Construction usually takes four or five days and may continue through incubation.

Common starlings are both monogamous

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time ( serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., pol ...

and polygamous

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marri ...

; although broods are generally brought up by one male and one female, occasionally the pair may have an extra helper. Pairs may be part of a colony, in which case several other nests may occupy the same or nearby trees. Males may mate with a second female while the first is still on the nest. The reproductive success of the bird is poorer in the second nest than it is in the primary nest and is better when the male remains monogamous.

Breeding

Breeding takes place during the spring and summer. Following copulation, the female lays eggs on a daily basis over a period of several days. If an egg is lost during this time, she will lay another to replace it. There are normally four or five eggs that are

Breeding takes place during the spring and summer. Following copulation, the female lays eggs on a daily basis over a period of several days. If an egg is lost during this time, she will lay another to replace it. There are normally four or five eggs that are ovoid

An oval () is a closed curve in a plane which resembles the outline of an egg. The term is not very specific, but in some areas ( projective geometry, technical drawing, etc.) it is given a more precise definition, which may include either o ...

in shape and pale blue or occasionally white, and they commonly have a glossy appearance. The colour of the eggs seems to have evolved through the relatively good visibility of blue at low light levels. The egg size is in length and in maximum diameter.

Incubation lasts thirteen days, although the last egg laid may take 24 hours longer than the first to hatch. Both parents share the responsibility of brooding the eggs, but the female spends more time incubating them than does the male, and is the only parent to do so at night when the male returns to the communal roost. The young are born blind and naked. They develop light fluffy down within seven days of hatching and can see within nine days. Once the chicks are able to regulate their body temperature, about six days after hatching,Marjoniemi (2001) p. 19. the adults largely cease removing droppings from the nest. Prior to that, the fouling would wet both the chicks' plumage and the nest material, thereby reducing their effectiveness as insulation and increasing the risk of chilling the hatchlings.Burton (1985) p. 187. Nestlings remain in the nest for three weeks, where they are fed continuously by both parents. Fledglings continue to be fed by their parents for another one or two weeks. A pair can raise up to three broods per year, frequently reusing and relining the same nest, although two broods is typical, or just one north of 48°N. Within two months, most juveniles will have moulted and gained their first basic plumage. They acquire their adult plumage the following year. As with other passerines, the nest is kept clean and the chicks' faecal sacs are removed by the adults.

Intraspecific

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organis ...

brood parasites

Brood parasites are animals that rely on others to raise their young. The strategy appears among birds, insects and fish. The brood parasite manipulates a host, either of the same or of another species, to raise its young as if it were its o ...

are common in common starling nests. Female "floaters" (unpaired females during the breeding season) present in colonies often lay eggs in another pair's nest. Fledglings have also been reported to invade their own or neighbouring nests and evict a new brood. Common starling nests have a 48% to 79% rate of successful fledging, although only 20% of nestlings survive to breeding age; the adult survival rate is closer to 60%. The average life span is about 2–3 years, with a longevity record of 22 years 11 months.

Predators and parasites

A majority of starling predators are avian. The typical response of starling groups is to take flight, with a common sight being undulating flocks of starling flying high in quick and agile patterns. Their abilities in flight are seldom matched by birds of prey. Adult common starlings are hunted byhawk

Hawks are birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are widely distributed and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

* The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks and others. This subfa ...

s such as the northern goshawk

The northern goshawk (; ''Accipiter gentilis'') is a species of medium-large raptor in the family Accipitridae, a family which also includes other extant diurnal raptors, such as eagles, buzzards and harriers. As a species in the genus '' Acci ...

(''Accipiter gentilis'') and Eurasian sparrowhawk

The Eurasian sparrowhawk (''Accipiter nisus''), also known as the northern sparrowhawk or simply the sparrowhawk, is a small bird of prey in the family Accipitridae. Adult male Eurasian sparrowhawks have bluish grey upperparts and orange-barr ...

(''Accipiter nisus''),Génsbøl (1984) pp. 142, 151. and falcon

Falcons () are birds of prey in the genus ''Falco'', which includes about 40 species. Falcons are widely distributed on all continents of the world except Antarctica, though closely related raptors did occur there in the Eocene.

Adult falcons ...

s including the peregrine falcon

The peregrine falcon (''Falco peregrinus''), also known as the peregrine, and historically as the duck hawk in North America, is a cosmopolitan bird of prey (raptor) in the family Falconidae. A large, crow-sized falcon, it has a blue-grey bac ...

(''Falco peregrinus''), Eurasian hobby (''Falco subbuteo'') and common kestrel

The common kestrel (''Falco tinnunculus'') is a bird of prey species belonging to the kestrel group of the falcon family Falconidae. It is also known as the European kestrel, Eurasian kestrel, or Old World kestrel. In the United Kingdom, where n ...

(''Falco tinnunculus'').Génsbøl (1984) pp. 239, 254, 273. Slower raptors like black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

and red kites (''Milvus migrans & milvus''), eastern imperial eagle

The eastern imperial eagle (''Aquila heliaca'') is a large bird of prey that breeds in southeastern Europe and extensively through West and Central Asia. Most populations are migratory and winter in northeastern Africa, the Middle East and South ...

(''Aquila heliaca''), common buzzard

The common buzzard (''Buteo buteo'') is a medium-to-large bird of prey which has a large range. A member of the genus '' Buteo'', it is a member of the family Accipitridae. The species lives in most of Europe and extends its breeding range acr ...

(''Buteo buteo'') and Australasian harrier (''Circus approximans'') tend to take the more easily caught fledglings or juveniles.Génsbøl (1984) pp. 67, 74, 162. While perched in groups by night, they can be vulnerable to owls, including the little owl

The little owl (''Athene noctua''), also known as the owl of Athena or owl of Minerva, is a bird that inhabits much of the temperate and warmer parts of Europe, the Palearctic east to Korea, and North Africa. It was introduced into Britain at ...

(''Athene noctua''), long-eared owl (''Asio otus''), short-eared owl

The short-eared owl (''Asio flammeus'') is a widespread grassland species in the family Strigidae. Owls belonging to genus ''Asio'' are known as the eared owls, as they have tufts of feathers resembling mammalian ears. These "ear" tufts may or ...

(''Asio flammeus''), barn owl

The barn owl (''Tyto alba'') is the most widely distributed species of owl in the world and one of the most widespread of all species of birds, being found almost everywhere except for the polar and desert regions, Asia north of the Himala ...

(''Tyto alba''), tawny owl

The tawny owl (''Strix aluco''), also called the brown owl, is commonly found in woodlands across Europe to western Siberia, and has seven recognized subspecies. It is a stocky, medium-sized owl, whose underparts are pale with dark streaks, a ...

(''Strix aluco'') and Eurasian eagle-owl

The Eurasian eagle-owl (''Bubo bubo'') is a species of eagle-owl that resides in much of Eurasia. It is also called the Uhu and it is occasionally abbreviated to just the eagle-owl in Europe. It is one of the largest species of owl, and femal ...

(''Bubo bubo'').

More than twenty species of hawk

Hawks are birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are widely distributed and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

* The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks and others. This subfa ...

, owl and falcon

Falcons () are birds of prey in the genus ''Falco'', which includes about 40 species. Falcons are widely distributed on all continents of the world except Antarctica, though closely related raptors did occur there in the Eocene.

Adult falcons ...

are known to occasionally predate feral starlings in North America, though the most regular predators of adults are likely to be urban-living peregrine falcon

The peregrine falcon (''Falco peregrinus''), also known as the peregrine, and historically as the duck hawk in North America, is a cosmopolitan bird of prey (raptor) in the family Falconidae. A large, crow-sized falcon, it has a blue-grey bac ...

s or merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and leg ...

s (''Falco columbarius''). Common mynas (''Acridotheres tristis'') sometimes evict eggs, nestlings and adult common starlings from their nests, and the lesser honeyguide

The lesser honeyguide (''Indicator minor'') is a species of bird in the family Indicatoridae.

Range

It is found in Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Repu ...

(''Indicator minor''), a brood parasite

Brood parasites are animals that rely on others to raise their young. The strategy appears among birds, insects and fish. The brood parasite manipulates a host, either of the same or of another species, to raise its young as if it were it ...

, uses the common starling as a host. Starlings are more commonly the culprits rather than victims of nest eviction however, especially towards other starlings and woodpecker

Woodpeckers are part of the bird family Picidae, which also includes the piculets, wrynecks, and sapsuckers. Members of this family are found worldwide, except for Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, Madagascar, and the extreme polar regions ...

s. Nests can be raided by mammals capable of climbing to them, such as small mustelids ('' Mustela'' spp.), raccoon

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the common raccoon to distinguish it from other species, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest of the procyonid family, having a body length of , and a body weight of ...

s (''Procyon lotor'') and squirrel

Squirrels are members of the family Sciuridae, a family that includes small or medium-size rodents. The squirrel family includes tree squirrels, ground squirrels (including chipmunks and prairie dogs, among others), and flying squirrels. ...

s (''Sciurus'' spp.), and cats may catch the unwary.

Common starlings are hosts to a wide range of parasites. A survey of three hundred common starlings from six US states found that all had at least one type of parasite; 99% had external fleas, mites or ticks, and 95% carried internal parasites, mostly various types of worm. Blood-sucking

Hematophagy (sometimes spelled haematophagy or hematophagia) is the practice by certain animals of feeding on blood (from the Greek words αἷμα ' "blood" and φαγεῖν ' "to eat"). Since blood is a fluid tissue rich in nutritious ...

species leave their host when it dies, but other external parasites stay on the corpse. A bird with a deformed bill was heavily infested with '' Mallophaga'' lice, presumably due to its inability to remove vermin.

The hen flea ('' Ceratophyllus gallinae'') is the most common

The hen flea ('' Ceratophyllus gallinae'') is the most common flea

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, ...

in their nests.Rothschild & Clay (1953) pp. 84–85. The small, pale house-sparrow flea ''C. fringillae'', is also occasionally found there and probably arises from the habit of its main host of taking over the nests of other species. This flea does not occur in the US, even on house sparrow

The house sparrow (''Passer domesticus'') is a bird of the Old World sparrow, sparrow family Passeridae, found in most parts of the world. It is a small bird that has a typical length of and a mass of . Females and young birds are coloured pale ...

s.Rothschild & Clay (1953) p. 115. Lice

Louse ( : lice) is the common name for any member of the clade Phthiraptera, which contains nearly 5,000 species of wingless parasitic insects. Phthiraptera has variously been recognized as an order, infraorder, or a parvorder, as a resul ...

include ''Menacanthus eurystemus'', ''Brueelia nebulosa'' and ''Stumidoecus sturni''. Other arthropod parasites include ''Ixodes

''Ixodes'' is a genus of hard-bodied ticks (family Ixodidae). It includes important disease vectors of animals and humans ( tick-borne disease), and some species (notably '' Ixodes holocyclus'') inject toxins that can cause paralysis. Som ...

'' tick

Ticks (order Ixodida) are parasitic arachnids that are part of the mite superorder Parasitiformes. Adult ticks are approximately 3 to 5 mm in length depending on age, sex, species, and "fullness". Ticks are external parasites, living ...

s and mite

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods). Mites span two large orders of arachnids, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari, but genetic analysis does not show clear e ...

s such as ''Analgopsis passerinus'', ''Boydaia stumi'', '' Dermanyssus gallinae'', ''Ornithonyssus bursa

''Ornithonyssus bursa'' (also known as the tropical fowl mite) is a species of mite.

It is most often a parasite of birds, but also has been found to bite humans and two species of mammals.

It usually lives in birds' feathers, but for laying its ...

'', ''O. sylviarum'', '' Proctophyllodes'' species, ''Pteronyssoides truncatus'' and ''Trouessartia rosteri''.

Higgins ''et al'' (2006) 1960

. The hen mite ''D. gallinae'' is itself preyed upon by the predatory mite '' Androlaelaps casalis''. The presence of this control on numbers of the parasitic species may explain why birds are prepared to reuse old nests.Lesna, I; Wolfs, P; Faraji, F; Roy, L; Komdeur, J; Sabelis, M W. "Candidate predators for biological control of the poultry red mite ''Dermanyssus gallinae''" in Sparagano (2009) pp. 75–76. Flying insects that parasitise common starlings include the louse-fly ''Omithomya nigricornis'' and the

saprophagous

Saprotrophic nutrition or lysotrophic nutrition is a process of chemoheterotrophic extracellular digestion involved in the processing of decayed (dead or waste) organic matter. It occurs in saprotrophs, and is most often associated with fungi (f ...

fly '' Carnus hemapterus''. The latter species breaks off the feathers of its host and lives on the fats produced by growing plumage.Rothschild & Clay (1953) p. 222. Larvae of the moth '' Hofmannophila pseudospretella'' are nest scavengers, which feed on animal material such as faeces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

or dead nestlings.Rothschild & Clay (1953) p. 251. Protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histo ...

n blood parasites of the genus ''Haemoproteus

''Haemoproteus'' is a genus of alveolates that are parasitic in birds, reptiles and amphibians. Its name is derived from Greek: ''Haima'', "blood", and ''Proteus'', a sea god who had the power of assuming different shapes. The name ''Haemopr ...

'' have been found in common starlings,Rothschild & Clay (1953) p. 169. but a better known pest is the brilliant scarlet nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant- parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a bro ...

'' Syngamus trachea''. This worm moves from the lungs to the trachea

The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all air- breathing animals with lungs. The trachea extends from t ...

and may cause its host to suffocate. In Britain, the rook and the common starling are the most infested wild birds.Rothschild & Clay (1953) pp. 180–181. Other recorded internal parasites include the spiny-headed worm ''Prosthorhynchus transverses''.Rothschild & Clay (1953) p. 189.

Common starlings may contract avian tuberculosis, avian malaria

Avian malaria is a parasitic disease of birds, caused by parasite species belonging to the genera '' Plasmodium'' and '' Hemoproteus'' (phylum Apicomplexa, class Haemosporidia, family Plasmoiidae). The disease is transmitted by a dipteran vecto ...

Rothschild & Clay (1953) pp. 235–237. and retrovirus

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. Once inside the host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptas ...

-induced lymphoma

Lymphoma is a group of blood and lymph tumors that develop from lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). In current usage the name usually refers to just the cancerous versions rather than all such tumours. Signs and symptoms may include en ...

s. Captive starlings often accumulate excess iron in the liver, a condition that can be prevented by adding black tea-leaves to the food.

Distribution and habitat

The global population of common starlings was estimated to be 310 million individuals in 2004, occupying a total area of . Widespread throughout the Northern Hemisphere, the bird is native toEurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

and is found throughout Europe, northern Africa (from Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

), India (mainly in the north but regularly extending farther south and extending into the Maldives) Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is ma ...

, the Middle East including Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, and northwestern China.

Common starlings in the south and west of Europe and south of latitude 40°N are mainly resident, although other populations migrate from regions where the winter is harsh, the ground frozen and food scarce. Large numbers of birds from northern Europe, Russia and Ukraine migrate south westwards or south eastwards. In the autumn, when immigrants are arriving from eastern Europe, many of Britain's common starlings are setting off for

Common starlings in the south and west of Europe and south of latitude 40°N are mainly resident, although other populations migrate from regions where the winter is harsh, the ground frozen and food scarce. Large numbers of birds from northern Europe, Russia and Ukraine migrate south westwards or south eastwards. In the autumn, when immigrants are arriving from eastern Europe, many of Britain's common starlings are setting off for Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese language, Aragonese and Occitan language, Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a pe ...

and North Africa. Other groups of birds are in passage across the country and the pathways of these different streams of bird may cross. Of the 15,000 birds ringed as nestlings in Merseyside

Merseyside ( ) is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in North West England, with a population of 1.38 million. It encompasses both banks of the Mersey Estuary and comprises five metropolitan boroughs: Knowsley, St Helens, Sefton, Wir ...

, England, individuals have been recovered at various times of year as far afield as Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Germany and the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

. Small numbers of common starlings have sporadically been observed in Japan and Hong Kong but it is unclear whence these birds originated. In North America, northern populations have developed a migration pattern, vacating much of Canada in winter.Sibley (2000) p. 416. Birds in the east of the country move southwards, and those from farther west winter in the southwest of the US.

Common starlings prefer urban or suburban areas where artificial structures and trees provide adequate nesting and roosting

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweight ...