Ethel Rosenberg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

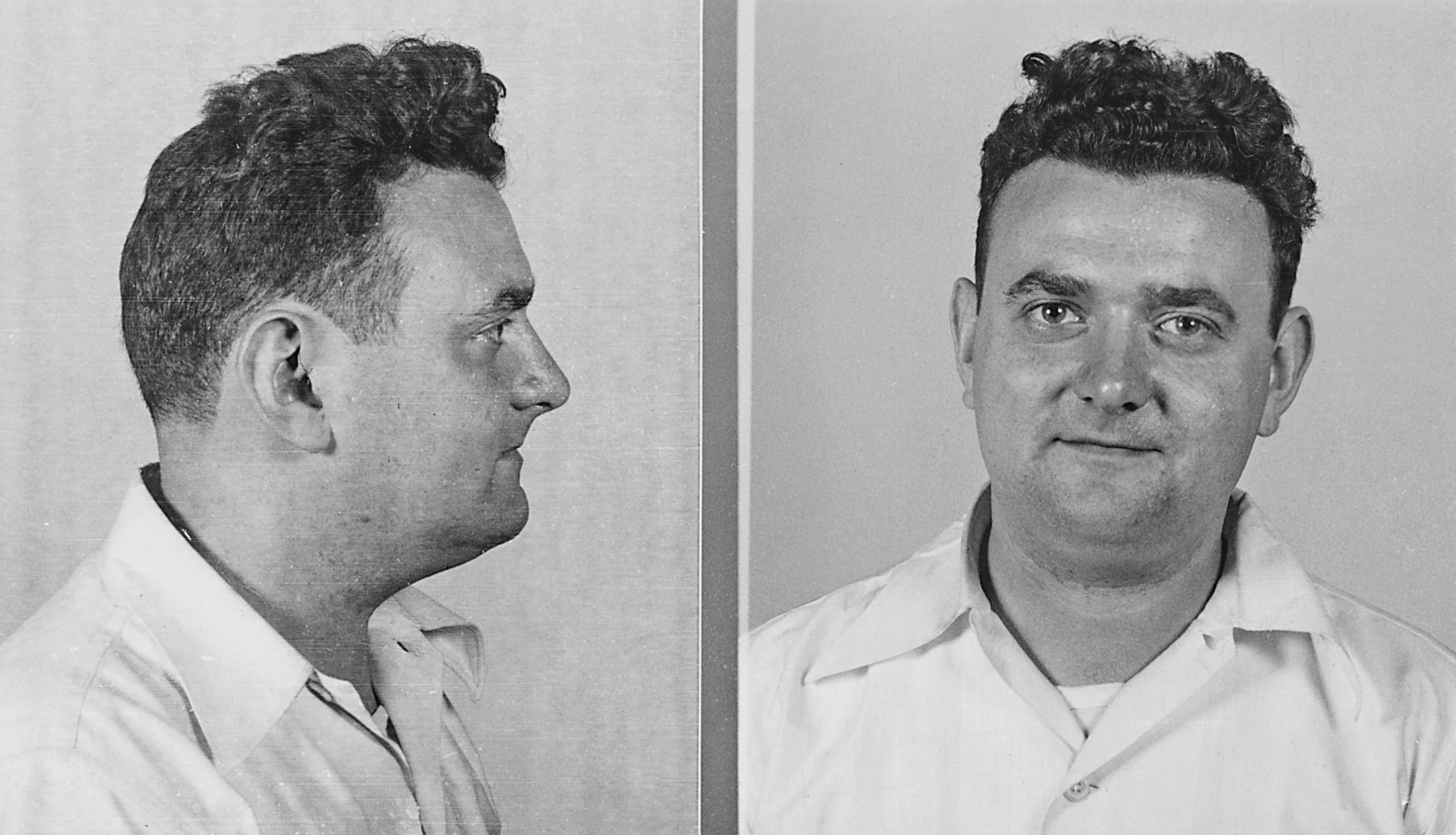

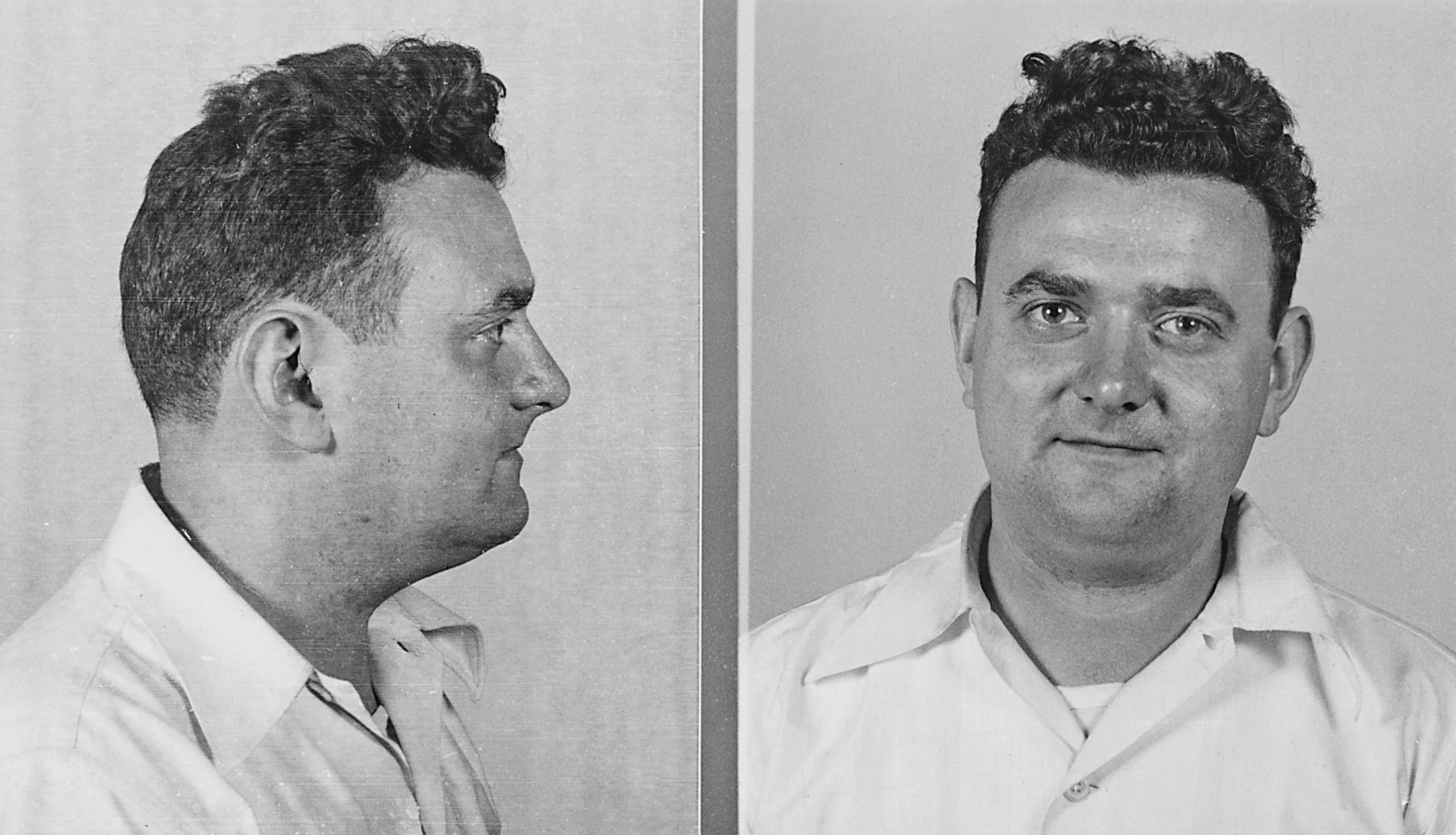

Julius Rosenberg (May 12, 1918 – June 19, 1953) and Ethel Rosenberg (; September 28, 1915 – June 19, 1953) were American citizens who were convicted of spying on behalf of the

Julius Rosenberg was born on May 12, 1918, in

Julius Rosenberg was born on May 12, 1918, in

In January 1950, the U.S. discovered that

In January 1950, the U.S. discovered that

Twenty senior government officials met secretly on February 8, 1950, to discuss the Rosenberg case. Gordon Dean, the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, said: "It looks as though Rosenberg is the kingpin of a very large ring, and if there is any way of breaking him by having the shadow of a death penalty over him, we want to do it."

Twenty senior government officials met secretly on February 8, 1950, to discuss the Rosenberg case. Gordon Dean, the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, said: "It looks as though Rosenberg is the kingpin of a very large ring, and if there is any way of breaking him by having the shadow of a death penalty over him, we want to do it."

The trial of the Rosenbergs and Sobell on federal espionage charges began on March 6, 1951, in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Judge Irving Kaufman presided over the trial, with Assistant U.S. Attorney Irving Saypol leading the prosecution and criminal defense lawyer Emmanuel Bloch representing the Rosenbergs. The prosecution's primary witness, David Greenglass, said that he turned over to Julius Rosenberg a sketch of the cross-section of an implosion-type atom bomb. This was the "

The trial of the Rosenbergs and Sobell on federal espionage charges began on March 6, 1951, in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Judge Irving Kaufman presided over the trial, with Assistant U.S. Attorney Irving Saypol leading the prosecution and criminal defense lawyer Emmanuel Bloch representing the Rosenbergs. The prosecution's primary witness, David Greenglass, said that he turned over to Julius Rosenberg a sketch of the cross-section of an implosion-type atom bomb. This was the "

In 2001, David Greenglass recanted his testimony about his sister having typed the notes. He said, "I frankly think my wife did the typing, but I don't remember." He said he gave false testimony to protect himself and his wife, Ruth, and that he was encouraged by the prosecution to do so. "My wife is more important to me than my sister. Or my mother or my father, OK? And she was the mother of my children."

He refused to express remorse for his decision to betray his sister, saying only that he did not realize that the prosecution would push for the death penalty. He stated, "I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister."

In 2001, David Greenglass recanted his testimony about his sister having typed the notes. He said, "I frankly think my wife did the typing, but I don't remember." He said he gave false testimony to protect himself and his wife, Ruth, and that he was encouraged by the prosecution to do so. "My wife is more important to me than my sister. Or my mother or my father, OK? And she was the mother of my children."

He refused to express remorse for his decision to betray his sister, saying only that he did not realize that the prosecution would push for the death penalty. He stated, "I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister."

In 2008,

In 2008,

The Rosenbergs' two sons, Michael and Robert, spent years trying to prove the innocence of their parents. They were orphaned by the executions and were not adopted by their many aunts or uncles, although they initially spent time under the care of their grandmothers and in a children's home. They were adopted by the social activist Abel Meeropol and his wife Anne, and assumed the Meeropol surname.

After

The Rosenbergs' two sons, Michael and Robert, spent years trying to prove the innocence of their parents. They were orphaned by the executions and were not adopted by their many aunts or uncles, although they initially spent time under the care of their grandmothers and in a children's home. They were adopted by the social activist Abel Meeropol and his wife Anne, and assumed the Meeropol surname.

After

Green Elms Press

2010. * Carmichael, Virginia .''Framing history: the Rosenberg story and the Cold War'', (University of Minnesota Press, 1993) * Clune, Lori. "Great Importance World-Wide: Presidential Decision-Making and the Executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg." ''American Communist History'' 10.3 (2011): 263–284

online

* Doctorow, E. L. ''The Book of Daniel''. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2007. * Deborah Friedell, "How Utterly Depreaved!" (review of

Guide to the Playscript about the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg Espionage Trial

Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

An Interactive Rosenberg Espionage Ring Timeline and Archive

Timeline of Events Relating to the Rosenberg Trial.

Rosenberg trial transcript

(excerpts as HTML, and the entire 2,563-page transcript as a PDF file)

Documents relating to the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg Case, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

(summary only)

''Heir to an Execution''

– An HBO documentary by Ivy Meeropol, the granddaughter of Ethel and Julius.

* ttp://www.angelfire.com/zine2/robertmeeropol/ An Interview with Robert Meeropol about the adoption

National Committee to Reopen the Rosenberg Case

Annotated bibliography for Ethel Rosenberg from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

Annotated bibliography for Julius Rosenberg from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

The Cold War International History Project (CWIHP)

for Alexander Vassiliev's Notebooks

Rosenberg Son: "My Parents Were Executed Under the Unconstitutional Espionage Act"

– video report by

History on Trial: The Rosenberg Case in E.L. Doctorow's ''The Book of Daniel''

by Santiago Juan-Navarro from ''The Grove: Working Papers on English Studies'', Vol 6, 1999.

Julius Rosenberg at court sentenced to death

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20170222113748/http://www.imdb.com/character/ch0122928/ Ethel Rosenbergon

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. The couple were convicted of providing top-secret information about radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, weat ...

, sonar, jet propulsion

Jet propulsion is the propulsion of an object in one direction, produced by ejecting a jet of fluid in the opposite direction. By Newton's third law, the moving body is propelled in the opposite direction to the jet. Reaction engines operating on ...

engines, and valuable nuclear weapon design

Nuclear weapon designs are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

* pure fission weapons, the simplest and least technically ...

s. Convicted of espionage in 1951, they were executed by the federal government of the United States in 1953 at Sing Sing Correctional Facility

Sing Sing Correctional Facility, formerly Ossining Correctional Facility, is a maximum-security prison operated by the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision in the village of Ossining, New York. It is about north o ...

in Ossining, New York

Ossining may refer to:

*Ossining (town), New York, a town in Westchester County, New York state

*Ossining (village), New York, a village in the town of Ossining

* Ossining High School, a comprehensive public high school in Ossining village

* Ossin ...

, becoming the first American civilians to be executed for such charges and the first to receive that penalty during peacetime.

Other convicted co-conspirators were sentenced to prison, including Ethel's brother, David Greenglass

David Greenglass (March 2, 1922 – July 1, 2014) was an atomic spy for the Soviet Union who worked on the Manhattan Project. He was briefly stationed at the Clinton Engineer Works uranium enrichment facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and then ...

(who had made a plea agreement

A plea bargain (also plea agreement or plea deal) is an agreement in criminal law proceedings, whereby the prosecutor provides a concession to the defendant in exchange for a plea of guilt or '' nolo contendere.'' This may mean that the defendan ...

), Harry Gold

Harry Gold (born Henrich Golodnitsky, December 11, 1910 – August 28, 1972) was a Swiss-born American laboratory chemist who was convicted as a courier for the Soviet Union passing atomic secrets from Klaus Fuchs, an agent of the Soviet Union, ...

, and Morton Sobell

Morton Sobell (April 11, 1917 – December 26, 2018) was an American engineer and Soviet spy during and after World War II; he was charged as part of a conspiracy which included Julius Rosenberg and his wife. Sobell worked on military and gover ...

. Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly af ...

, a German scientist working in Los Alamos, was convicted in the United Kingdom.

For decades many people including the Rosenbergs' sons ( Michael and Robert Meeropol) maintained that Julius and Ethel were innocent of spying on their country and were victims of Cold War paranoia.

The extent of the Rosenbergs' activities came to light, however, when the U.S. government declassified information about them after the fall of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

. This declassified

Declassification is the process of ceasing a protective classification, often under the principle of freedom of information. Procedures for declassification vary by country. Papers may be withheld without being classified as secret, and even ...

information included a trove of decoded Soviet cables (code-name: Venona), which detailed Julius's role as a courier and recruiter for the Soviets, and information about Ethel's role as an accessory who helped recruit her brother David into the spy ring and did clerical tasks such as typing up documents that Julius then passed to the Soviets. In 2008, the National Archives of the United States published most of the grand jury testimony related to the prosecution

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the Civil law (legal system), civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the ...

of the Rosenbergs.

Early lives and education

Julius Rosenberg was born on May 12, 1918, in

Julius Rosenberg was born on May 12, 1918, in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

to a family of Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

immigrants

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, an ...

from the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

. The family moved to the Lower East Side

The Lower East Side, sometimes abbreviated as LES, is a historic neighborhood in the southeastern part of Manhattan in New York City. It is located roughly between the Bowery and the East River from Canal to Houston streets.

Traditionally a ...

by the time Julius was 11. His parents worked in the shops of the Lower East Side

The Lower East Side, sometimes abbreviated as LES, is a historic neighborhood in the southeastern part of Manhattan in New York City. It is located roughly between the Bowery and the East River from Canal to Houston streets.

Traditionally a ...

as Julius attended Seward Park High School __NOTOC__

The Seward Park Campus is a "vertical campus" of the New York City Department of Education located at 350 Grand Street at the corner of Essex Street, in the Lower East Side/ Cooperative Village neighborhoods of Manhattan, New York City ...

. Julius became a leader in the Young Communist League USA

The Young Communist League USA (YCLUSA) is a communist youth organization in the United States. The stated aim of the League is the development of its members into Communists, through studying Marxism–Leninism and through active participation ...

while at City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a public university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York City. Founded in 1847, Cit ...

during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagion ...

. In 1939, he graduated with a degree in electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

.

Ethel Greenglass was born on September 28, 1915, to a Jewish family in Manhattan, New York City

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. She had a brother, David Greenglass

David Greenglass (March 2, 1922 – July 1, 2014) was an atomic spy for the Soviet Union who worked on the Manhattan Project. He was briefly stationed at the Clinton Engineer Works uranium enrichment facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and then ...

. She originally was an aspiring actress and singer

Singing is the act of creating musical sounds with the voice. A person who sings is called a singer, artist or vocalist (in jazz and/or popular music). Singers perform music ( arias, recitatives, songs, etc.) that can be sung with or withou ...

, but eventually took a secretarial job at a shipping company. She became involved in labor disputes and joined the Young Communist League, where she met Julius in 1936. They married in 1939.

Espionage

Julius Rosenberg joined theArmy Signal Corps

The United States Army Signal Corps (USASC) is a branch of the United States Army that creates and manages communications and information systems for the command and control of combined arms forces. It was established in 1860, the brainchild of Ma ...

Engineering Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, in 1940, where he worked as an engineer-inspector until 1945. He was discharged when the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

discovered his previous membership in the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

. Important research on electronics, communications, radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, weat ...

and guided missile

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket i ...

controls was undertaken at Fort Monmouth

Fort Monmouth is a former installation of the Department of the Army in Monmouth County, New Jersey. The post is surrounded by the communities of Eatontown, Tinton Falls and Oceanport, New Jersey, and is located about from the Atlantic Ocean. ...

during World War II.

According to a 2001 book by his former handler Alexander Feklisov, Rosenberg was originally recruited to spy for the interior ministry of the Soviet Union, NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

, on Labor Day

Labor Day is a federal holiday in the United States celebrated on the first Monday in September to honor and recognize the American labor movement and the works and contributions of laborers to the development and achievements of the United S ...

1942 by former spymaster

A spymaster is the person that leads a spy ring, or a secret service (such as an intelligence agency

An intelligence agency is a government agency responsible for the collection, analysis, and exploitation of information in support of law ...

Semyon Semyonov

Semyon Markovich Semyonov (1911–1986) was a Soviet intelligence agent, best known for handling convicted Soviet spy Julius Rosenberg.

Background

Semyonov was born Samuil Markovich Taubman in Odessa and graduated from the Moscow Textile Institut ...

. By this time, following the invasion by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

in June 1941, the Soviet Union had become an ally of the Western powers, which included the United States after Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the R ...

. Rosenberg had been introduced to Semyonov by Bernard Schuster, a high-ranking member of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

and NKVD liaison for Earl Browder

Earl Russell Browder (May 20, 1891 – June 27, 1973) was an American politician, communist activist and leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Browder was the General Secretary of the CPUSA during the 1930s and first half of the 1940s.

Durin ...

. After Semyonov was recalled to Moscow in 1944 his duties were taken over by Feklisov.

Rosenberg provided thousands of classified reports from Emerson Radio

Emerson Radio Corporation is one of the United States' largest volume consumer electronics distributors and has a recognized trademark in continuous use since 1912. The company designs, markets, and licenses many product lines worldwide, inc ...

, including a complete proximity fuse

A proximity fuze (or fuse) is a fuze that detonates an explosive device automatically when the distance to the target becomes smaller than a predetermined value. Proximity fuzes are designed for targets such as planes, missiles, ships at sea, a ...

. Under Feklisov's supervision, Rosenberg recruited sympathetic individuals into NKVD service, including Joel Barr

Joel Barr (January 1, 1916 – August 1, 1998), also Iozef Veniaminovich Berg and Joseph Berg, was part of the Soviet Atomic Spy Ring.

Background

Born Joyel Barr in New York City, to immigrant parents of Ukrainian Jewish origin. He attended Ci ...

, Alfred Sarant

Alfred Epaminondas Sarant, also known as Filipp Georgievich Staros and Philip Georgievich Staros (September 26, 1918 – March 12, 1979), was an engineer and a member of the Communist party in New York City in 1944. He was part of the Rosenbe ...

, William Perl, and Morton Sobell

Morton Sobell (April 11, 1917 – December 26, 2018) was an American engineer and Soviet spy during and after World War II; he was charged as part of a conspiracy which included Julius Rosenberg and his wife. Sobell worked on military and gover ...

, also an engineer. Perl supplied Feklisov, under Rosenberg's direction, with thousands of documents from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a United States federal agency founded on March 3, 1915, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. On October 1, 1958, the agency was dissolved and its assets ...

, including a complete set of design and production drawings for Lockheed's P-80 Shooting Star

The Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star was the first jet fighter used operationally by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) during World War II. Designed and built by Lockheed in 1943 and delivered just 143 days from the start of design, pro ...

, the first U.S. operational jet fighter

Fighter aircraft are fixed-wing military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air superiority of the battlespace. Domination of the airspace above a battlefield ...

. Feklisov learned through Rosenberg that Ethel's brother David Greenglass

David Greenglass (March 2, 1922 – July 1, 2014) was an atomic spy for the Soviet Union who worked on the Manhattan Project. He was briefly stationed at the Clinton Engineer Works uranium enrichment facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and then ...

was working on the top-secret

Classified information is material that a government body deems to be sensitive information that must be protected. Access is restricted by law or regulation to particular groups of people with the necessary security clearance and need to kno ...

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project ...

at the Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, in ...

; he directed Julius to recruit Greenglass.

In February 1944, Rosenberg succeeded in recruiting a second source of Manhattan Project information, engineer Russell McNutt, who worked on designs for the plants at Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is a U.S. multiprogram science and technology national laboratory sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and administered, managed, and operated by UT–Battelle as a federally funded research and ...

. For this success Rosenberg received a $100 bonus. McNutt's employment provided access to secrets about processes for manufacturing weapons-grade uranium

Weapons-grade nuclear material is any fissionable nuclear material that is pure enough to make a nuclear weapon or has properties that make it particularly suitable for nuclear weapons use. Plutonium and uranium in grades normally used in nucle ...

.

The USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and the U.S. were allies during World War II, but the Americans did not share information with, or seek assistance from, the Soviet Union regarding the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project ...

. The West was shocked by the speed with which the Soviets were able to stage their first nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

, "Joe 1

The RDS-1 (russian: РДС-1), also known as Izdeliye 501 (device 501) and First Lightning (), was the nuclear bomb used in the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test. The United States assigned it the code-name Joe-1, in reference to Joseph S ...

", on August 29, 1949. However, the head official of the Soviet nuclear project, Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

, used foreign intelligence, which he did not trust by default, only as a third-party check, rather than giving it directly to the design teams, who he did not clear to know about the espionage efforts, and the development was indigenous; considering that the pace of the Soviet program was set primarily by the amount of uranium that it could procure, it is difficult for scholars to judge accurately how much time was saved, if any.

Rosenberg case

Arrest

In January 1950, the U.S. discovered that

In January 1950, the U.S. discovered that Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly af ...

, a German refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

theoretical physicist

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experimen ...

working for the British mission in the Manhattan Project, had given key documents to the Soviets throughout the war. Fuchs identified his courier as American Harry Gold

Harry Gold (born Henrich Golodnitsky, December 11, 1910 – August 28, 1972) was a Swiss-born American laboratory chemist who was convicted as a courier for the Soviet Union passing atomic secrets from Klaus Fuchs, an agent of the Soviet Union, ...

, who was arrested on May 23, 1950.

On June 15, 1950, David Greenglass was arrested by the FBI for espionage and soon confessed to having passed secret information on to the USSR through Gold. He also claimed that his sister Ethel's husband Julius Rosenberg had convinced David's wife Ruth to recruit him while visiting him in Albuquerque, New Mexico

Albuquerque ( ; ), ; kee, Arawageeki; tow, Vakêêke; zun, Alo:ke:k'ya; apj, Gołgéeki'yé. abbreviated ABQ, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico. Its nicknames, The Duke City and Burque, both reference its founding in ...

, in 1944. He said Julius had passed secrets and thus linked him to the Soviet contact agent Anatoli Yakovlev. This connection would be necessary as evidence if there was to be a conviction for espionage of the Rosenbergs.

On July 17, 1950, Julius Rosenberg was arrested on suspicion of espionage based on David Greenglass's confession. On August 11, 1950, Ethel Rosenberg was arrested after testifying before a grand jury (see section, below).

Another conspirator, Morton Sobell

Morton Sobell (April 11, 1917 – December 26, 2018) was an American engineer and Soviet spy during and after World War II; he was charged as part of a conspiracy which included Julius Rosenberg and his wife. Sobell worked on military and gover ...

, fled with his family to Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley of M ...

after Greenglass was arrested. They took assumed names and he tried to figure out a way to reach Europe without a passport. Abandoning that effort, he returned to Mexico City. He claimed that he was kidnapped by members of the Mexican secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of ...

and driven to the U.S. border, where he was arrested by U.S. forces. The U.S. government claimed Sobell was arrested by the Mexican police for bank robbery on August 16, 1950, and extradited the next day to the United States in Laredo, Texas.

Grand jury

Twenty senior government officials met secretly on February 8, 1950, to discuss the Rosenberg case. Gordon Dean, the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, said: "It looks as though Rosenberg is the kingpin of a very large ring, and if there is any way of breaking him by having the shadow of a death penalty over him, we want to do it."

Twenty senior government officials met secretly on February 8, 1950, to discuss the Rosenberg case. Gordon Dean, the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, said: "It looks as though Rosenberg is the kingpin of a very large ring, and if there is any way of breaking him by having the shadow of a death penalty over him, we want to do it." Myles Lane

Myles Stanley Joseph Lane (October 2, 1903 – August 6, 1987) was an American professional ice hockey player, college football player and coach, and New York Supreme Court justice. He played in the National Hockey League with the New York Ra ...

, a member of the prosecution team, said that the case against Ethel Rosenberg was "not too strong", but that it was "very important that she be convicted too, and given a stiff sentence." FBI director J Edgar Hoover wrote that "proceeding against the wife will serve as a lever" to make Julius talk.

Their case against Ethel Rosenberg was resolved 10 days before the start of the trial, when David and Ruth Greenglass were interviewed a second time. They were persuaded to change their original stories. David originally had said that he had passed the atomic data he had collected to Julius on a New York street corner. After being interviewed this second time, he said that he had given this information to Julius in the living room of the Rosenbergs' New York apartment. Ethel, at Julius's request, had taken his notes and "typed them up." In her re-interview, Ruth Greenglass expanded on her husband's version:

Julius then took the info into the bathroom and read it and when he came out he called Ethel and told her she had to type this information immediately ... Ethel then sat down at the typewriter which she placed on a bridge table in the living room and proceeded to type the information that David had given to Julius.As a result of this new testimony, all charges against Ruth Greenglass were dropped. On August 11, Ethel Rosenberg testified before a grand jury. For all questions, she asserted her right to not answer as provided by the U.S. Constitution's Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination. FBI agents took her into custody as she left the courthouse. Her attorney asked the U.S. commissioner to parole her in his custody over the weekend, so that she could make arrangements for her two young children. The request was denied. Julius and Ethel were put under pressure to incriminate others involved in the spy ring. Neither offered any further information. On August 17, the grand jury returned an indictment alleging 11 overt acts. Both Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were indicted, as were David Greenglass and Anatoli Yakovlev.

Trial and conviction

The trial of the Rosenbergs and Sobell on federal espionage charges began on March 6, 1951, in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Judge Irving Kaufman presided over the trial, with Assistant U.S. Attorney Irving Saypol leading the prosecution and criminal defense lawyer Emmanuel Bloch representing the Rosenbergs. The prosecution's primary witness, David Greenglass, said that he turned over to Julius Rosenberg a sketch of the cross-section of an implosion-type atom bomb. This was the "

The trial of the Rosenbergs and Sobell on federal espionage charges began on March 6, 1951, in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Judge Irving Kaufman presided over the trial, with Assistant U.S. Attorney Irving Saypol leading the prosecution and criminal defense lawyer Emmanuel Bloch representing the Rosenbergs. The prosecution's primary witness, David Greenglass, said that he turned over to Julius Rosenberg a sketch of the cross-section of an implosion-type atom bomb. This was the "Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the firs ...

" bomb dropped on Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the Na ...

, Japan, as opposed to a bomb with the "gun method" triggering device used in the "Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' ...

" bomb dropped on Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

.

On March 29, 1951, the Rosenbergs were convicted of espionage. They were sentenced to death on April 5 under Section 2 of the Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (Wa ...

, which provides that anyone convicted of transmitting or attempting to transmit to a foreign government "information relating to the national defense" may be imprisoned for life or put to death.

Prosecutor Roy Cohn

Roy Marcus Cohn (; February 20, 1927 – August 2, 1986) was an American lawyer and prosecutor who came to prominence for his role as Senator Joseph McCarthy's chief counsel during the Army–McCarthy hearings in 1954, when he assisted McCarth ...

later claimed that his influence led to both Kaufman and Saypol being appointed to the Rosenberg case, and that Kaufman imposed the death penalty based on Cohn's personal recommendation. Cohn would go on later to work for Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

, appointed as chief counsel to the investigations subcommittee during McCarthy's tenure as chairman of the Senate Government Operations Committee.

In imposing the death penalty, Kaufman noted that he held the Rosenbergs responsible not only for espionage but also for American deaths in the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{{ ...

:

I believe your conduct in putting into the hands of the Russians the A-bomb years before our best scientists predicted Russia would perfect the bomb has already caused, in my opinion, the Communist aggression in Korea, with the resultant casualties exceeding 50,000 and who knows but that millions more of innocent people may pay the price of your treason. Indeed, by your betrayal you undoubtedly have altered the course of history to the disadvantage of our country.The US government offered to spare the lives of both Julius and Ethel if Julius provided the names of other spies and they admitted their guilt. The Rosenbergs made a public statement: "By asking us to repudiate the truth of our innocence, the government admits its own doubts concerning our guilt ... we will not be coerced, even under pain of death, to bear false witness".

After conviction

Campaign for clemency

After the publication of an investigative series in the ''National Guardian

''The National Guardian'', later known as ''The Guardian'', was a left-wing independent weekly newspaper established in 1948 in New York City. The paper was founded by James Aronson, Cedric Belfrage and John T. McManus in connection with the 1948 ...

'' and the formation of the National Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg Case, some Americans came to believe both Rosenbergs were innocent or had received too harsh a sentence, particularly Ethel. A campaign was started to try to prevent the couple's execution. Between the trial and the executions, there were widespread protests and claims of antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

; the charges of antisemitism were widely believed abroad, but not among the vast majority in the United States. At a time when American fears about communism were high, the Rosenbergs did not receive support from mainstream Jewish organizations. The American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". ...

refused to acknowledge any violations of civil liberties in the case.

Across the world, especially in Western European capitals, there were numerous protests with picketing and demonstrations in favor of the Rosenbergs, along with editorials in otherwise pro-American newspapers, and a plea for clemency from the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

. President Eisenhower, supported by public opinion and the media at home, ignored the overseas demands.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and litera ...

, a Marxist existentialist philosopher and writer who won the Nobel Prize for Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

, described the trial as

a legalOthers, including non-Communists such aslynching Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...which smears with blood a whole nation. By killing the Rosenbergs, you have quite simply tried to halt the progress of science by human sacrifice. Magic,witch-hunt A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America took place in the Early Modern perio ...s, autos-da-fé, sacrifices – we are here getting to the point: your country is sick with fear ... you are afraid of the shadow of your own bomb.

Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the su ...

and Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in the d ...

, a Nobel Prize-winning physical chemist, as well as Communists or other left-leaning figures such as Nelson Algren

Nelson Algren (born Nelson Ahlgren Abraham; March 28, 1909 – May 9, 1981) was an American writer. His 1949 novel ''The Man with the Golden Arm'' won the National Book Award and was adapted as the 1955 film of the same name.

Algren articulated ...

, Bertolt Brecht

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known professionally as Bertolt Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a pl ...

, Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, Dashiell Hammett

Samuel Dashiell Hammett (; May 27, 1894 – January 10, 1961) was an American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. He was also a screenwriter and political activist. Among the enduring characters he created are Sam Spade ('' ...

, Frida Kahlo

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country's popular culture, s ...

, and Diego Rivera

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez, known as Diego Rivera (; December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957), was a prominent Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the ...

, protested the position of the American government in what the French termed the U.S. Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

. Einstein and Urey pleaded with President Truman to pardon the Rosenbergs. In May 1951, Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th century, he is ...

wrote for the communist French newspaper ''L'Humanité

''L'Humanité'' (; ), is a French daily newspaper. It was previously an organ of the French Communist Party, and maintains links to the party. Its slogan is "In an ideal world, ''L'Humanité'' would not exist."

History and profile

Pre-World Wa ...

'', "The hours count. The minutes count. Do not let this crime against humanity take place." The all-black labor union International Longshoremen's Association

The International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) is a North American labor union representing longshore workers along the East Coast of the United States and Canada, the Gulf Coast, the Great Lakes, Puerto Rico, and inland waterways. The ILA h ...

Local 968 stopped working for a day in protest. Cinema artists such as Fritz Lang

Friedrich Christian Anton Lang (; December 5, 1890 – August 2, 1976), known as Fritz Lang, was an Austrian film director, screenwriter, and producer who worked in Germany and later the United States.Obituary ''Variety'', August 4, 1976, p. 6 ...

registered their protest. Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. ...

appealed to President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

to spare the couple, but Eisenhower refused on February 11, 1953. All other appeals were also unsuccessful.

Execution

The execution was delayed from the originally scheduled date of June 18, becauseSupreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

Associate Justice William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often ...

had granted a stay of execution

A stay of execution is a court order to temporarily suspend the execution of a court judgment or other court order. The word "execution" does not always mean the death penalty. It refers to the imposition of whatever judgment is being stayed and i ...

on the previous day. That stay resulted from intervention in the case by Fyke Farmer, a Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to t ...

lawyer whose efforts had previously been scorned by the Rosenbergs' attorney, Emanuel Hirsch Bloch.

The execution was scheduled for 11 p.m. that evening, during the Sabbath, which begins and ends around sunset. Bloch asked for more time, filing a complaint that execution on the Sabbath offended the defendants' Jewish heritage. Rhoda Laks, another attorney on the Rosenbergs' defense team, also made this argument before Judge Kaufman. The defense's strategy backfired. Kaufman, who also stated his concerns about executing the Rosenbergs on the Sabbath, rescheduled the execution for 8 p.m.—before sunset and the Sabbath—the regular time for executions at Sing Sing.

On June 19, 1953, Julius died after the first electric shock. Ethel's execution did not go smoothly. After she was given the normal course of three electric shocks, attendants removed the strapping and other equipment only to have doctors determine that Ethel's heart was still beating. Two more electric shocks were applied, and at the conclusion eyewitnesses reported that smoke rose from her head.

The funeral services were held in Brooklyn on June 21. Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were buried at Wellwood Cemetery

Wellwood Cemetery is a Jewish cemetery in West Babylon, New York. It was established as the annex to Beth David Cemetery in Elmont, New York. The cemetery comprises many sections, each under the auspices of a synagogue, landsmanschaft, or group ...

, a Jewish cemetery in Pinelawn, New York. ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fo ...

'' reported that 500 people attended, while some 10,000 stood outside:

The Rosenbergs were the only American civilians executed for espionage during the Cold War.

Soviet nuclear program

SenatorDaniel Patrick Moynihan

Daniel Patrick Moynihan (March 16, 1927 – March 26, 2003) was an American politician, diplomat and sociologist. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented New York in the United States Senate from 1977 until 2001 and served as an ...

, vice-chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, investigated how much the Soviet spy ring helped the USSR to build their bomb. Moynihan found that in 1945, physicist Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel Prize ...

estimated that the Soviets would be able to build their own bomb in five years. "Thanks to information provided by their agents", Moynihan wrote in his book ''Secrecy'', "they did it in four".

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev stu ...

, leader of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

from 1953 to 1964, said in his posthumously-published memoir that he "cannot specifically say what kind of help the Rosenbergs provided us" but that he learned from Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

and Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

that they "had provided very significant help in accelerating the production of our atomic bomb."

Boris V. Brokhovich, the engineer who later became director of Chelyabinsk-40, the plutonium production reactor and extraction facility that the Soviet Union used to create its first bomb material, alleged that Khrushchev was a "silly fool". He said the Soviets had developed their own bomb by trial and error. "You sat the Rosenbergs in the electric chair for nothing", he said. "We got nothing from the Rosenbergs."

The notes allegedly typed by Ethel apparently contained little that was directly used in the Soviet atomic bomb project. According to Alexander Feklisov, the former Soviet agent who was Julius's contact, the Rosenbergs did not provide the Soviet Union with any useful material about the atomic bomb: "He uliusdidn't understand anything about the atomic bomb and he couldn't help us."

Later developments

1995 Venona decryptions

TheVenona

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (later absorbed by the National Security Agency), which ran from February 1, 1943, until Octob ...

project was a United States counterintelligence

Counterintelligence is an activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting activities to prevent espionage, sabotage, assassinations or ot ...

program to decrypt messages transmitted by the intelligence agencies

An intelligence agency is a government agency responsible for the collection, analysis, and exploitation of information in support of law enforcement, national security, military, public safety, and foreign policy objectives.

Means of informatio ...

of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. Initiated when the Soviet Union was an ally of the U.S., the program continued during the Cold War when it was considered an enemy.

In 1995, the U.S. government made public many documents decoded by the Venona project, showing Julius Rosenberg's role as part of a productive ring of spies. For example, a 1944 cable (which gives the name of Ruth Greenglass in clear text) says that Ruth's husband David is being recruited as a spy by his sister (that is, Ethel Rosenberg) and her husband. The cable also makes clear that the sister's husband is involved enough in espionage to have his own codename ("Antenna" and later "Liberal"). Ethel did not have a codename, however, KGB messages which were contained in the Venona project's Vassiliev files, and which were not made public until 2009, revealed that both Ethel and Julius had regular contact with at least two KGB agents and were active in recruiting not only Ethel's brother David Greenglass, but also another Manhattan Project spy named Russell McNutt.

The messages decoded by the Venona project were not made public during the Rosenbergs' trial, which relied instead on testimony from their collaborators. Nevertheless, these decryptions formed the background of U.S. government investigation and prosecutions of American communists during the Cold War period.

2001 David Greenglass statements

In 2001, David Greenglass recanted his testimony about his sister having typed the notes. He said, "I frankly think my wife did the typing, but I don't remember." He said he gave false testimony to protect himself and his wife, Ruth, and that he was encouraged by the prosecution to do so. "My wife is more important to me than my sister. Or my mother or my father, OK? And she was the mother of my children."

He refused to express remorse for his decision to betray his sister, saying only that he did not realize that the prosecution would push for the death penalty. He stated, "I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister."

In 2001, David Greenglass recanted his testimony about his sister having typed the notes. He said, "I frankly think my wife did the typing, but I don't remember." He said he gave false testimony to protect himself and his wife, Ruth, and that he was encouraged by the prosecution to do so. "My wife is more important to me than my sister. Or my mother or my father, OK? And she was the mother of my children."

He refused to express remorse for his decision to betray his sister, saying only that he did not realize that the prosecution would push for the death penalty. He stated, "I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister."

2008 release of grand jury testimony

At the grand jury, Ruth Greenglass was asked, "Didn't you write he informationdown on a piece of paper?" She replied, "Yes, I wrote he informationdown on a piece of paper and ulius Rosenbergtook it with him." But at the trial, she testified that Ethel Rosenberg typed up notes about the atomic bomb. Numerous articles were published in 2008 related to the Rosenberg case.Deputy Attorney General of the United States

The United States deputy attorney general is the second-highest-ranking official in the United States Department of Justice and oversees the day-to-day operation of the Department. The deputy attorney general acts as attorney general during the ...

William P. Rogers, who had been part of the prosecution of the Rosenbergs, discussed their strategy at the time in relation to seeking the death sentence for Ethel. He said they had urged the death sentence for Ethel in an effort to extract a full confession from Julius. He reportedly said, "She called our bluff", as she made no effort to push her husband to any action.

2008 Morton Sobell's statements

In 2008,

In 2008, Morton Sobell

Morton Sobell (April 11, 1917 – December 26, 2018) was an American engineer and Soviet spy during and after World War II; he was charged as part of a conspiracy which included Julius Rosenberg and his wife. Sobell worked on military and gover ...

was interviewed after the revelations from grand jury testimony. He admitted that he had given documents to the Soviet contact, but said these had to do with defensive radar and weaponry. He confirmed that Julius Rosenberg was "in a conspiracy that delivered to the Soviets classified military and industrial information ... nthe atomic bomb," and "He never told me about anything else that he was engaged in."

He said that he thought the hand-drawn diagrams and other atomic-bomb details that were acquired by David Greenglass

David Greenglass (March 2, 1922 – July 1, 2014) was an atomic spy for the Soviet Union who worked on the Manhattan Project. He was briefly stationed at the Clinton Engineer Works uranium enrichment facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and then ...

and passed to Julius were of "little value" to the Soviet Union, and were used only to corroborate what they had already learned from the other atomic spies. He also said that he believed Ethel Rosenberg was aware of her husband's deeds, but took no part in them.

In a subsequent letter to ''The New York Times'', Sobell denied that he knew anything about Julius Rosenberg's alleged atomic espionage activities, and that the only thing he knew for sure was what he himself did in association with Julius Rosenberg.

2009 Vassiliev notebooks based on KGB archives

In 2009, extensive notes collected from KGB archives were made public in a book published byYale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universit ...

: ''Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America'', written by John Earl Haynes

John Earl Haynes (born 1944) is an American historian who worked as a specialist in 20th-century political history in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. He is known for his books on the subject of the American Communist and anti- ...

, Harvey Klehr

Harvey Elliott Klehr (born December 25, 1945) is a professor of politics and history at Emory University. Klehr is known for his books on the subject of the American Communist movement, and on Soviet espionage in America (many written jointly wit ...

, and Alexander Vassiliev

Alexander Vassiliev (russian: Александр Васильев; born 1962) is a Russian-British journalist, writer and espionage historian living in London who is a subject matter expert in the Soviet KGB and Russian SVR. A former officer ...

; Vassiliev's notebooks included KGB comments concerning Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

The notebooks make clear that the KGB considered Julius Rosenberg an effective agent and his wife Ethel an enthusiastic supporter of his work. According to Vassiliev, Julius and Ethel worked personally with KGB agents who were given the codenames ''Twain'' and ''Callistratus'' and were also described as being the ones who recruited Greenglass and McNutt for the Manhattan Project spy mission. Though the public release of Vassiliev's notebooks did not occur until 2009, the notebooks had in fact been originally intercepted during the Venona decryptions.

Rosenberg children

The Rosenbergs' two sons, Michael and Robert, spent years trying to prove the innocence of their parents. They were orphaned by the executions and were not adopted by their many aunts or uncles, although they initially spent time under the care of their grandmothers and in a children's home. They were adopted by the social activist Abel Meeropol and his wife Anne, and assumed the Meeropol surname.

After

The Rosenbergs' two sons, Michael and Robert, spent years trying to prove the innocence of their parents. They were orphaned by the executions and were not adopted by their many aunts or uncles, although they initially spent time under the care of their grandmothers and in a children's home. They were adopted by the social activist Abel Meeropol and his wife Anne, and assumed the Meeropol surname.

After Morton Sobell

Morton Sobell (April 11, 1917 – December 26, 2018) was an American engineer and Soviet spy during and after World War II; he was charged as part of a conspiracy which included Julius Rosenberg and his wife. Sobell worked on military and gover ...

's 2008 confession, they acknowledged their father had been involved in espionage, but said that whatever atomic bomb information he passed to the Russians was, at best, superfluous, that the case was riddled with prosecutorial and judicial misconduct, that their mother was convicted on flimsy evidence to place leverage on her husband, and that neither deserved the death penalty.

Michael and Robert co-wrote a book about their and their parents' lives, ''We Are Your Sons: The Legacy of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg'' (1975). Robert wrote a later memoir, ''An Execution in the Family: One Son's Journey'' (2003). In 1990, he founded the Rosenberg Fund for Children

The Rosenberg Fund for Children (RFC) is a public foundation started in 1990 by Robert Meeropol and named in honor of his parents Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, the only two United States civilians executed for conspiracy to commit espionage during ...

, a nonprofit foundation that provides support for children of targeted liberal activists, and youth who are targeted as activists.

Michael's daughter, Ivy Meeropol, directed a 2004 documentary about her grandparents, ''Heir to an Execution'', which was featured at the Sundance Film Festival

The Sundance Film Festival (formerly Utah/US Film Festival, then US Film and Video Festival) is an annual film festival organized by the Sundance Institute. It is the largest independent film festival in the United States, with more than 46,6 ...

.

Their sons' current position is that Julius was legally guilty of the conspiracy charge, though not of atomic spying, while Ethel was only generally aware of his activities. The children say that their father did not deserve the death penalty and that their mother was wrongly convicted. They continue to campaign for Ethel to be posthumously legally exonerated.

In 2015, following the most recent grand jury transcript release, Michael and Robert Meeropol called on U.S. President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

's administration to acknowledge that Ethel Rosenberg's conviction and execution was wrongful and to issue a proclamation exonerating her.

In March 2016, Michael and Robert (via the Rosenberg Fund for Children

The Rosenberg Fund for Children (RFC) is a public foundation started in 1990 by Robert Meeropol and named in honor of his parents Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, the only two United States civilians executed for conspiracy to commit espionage during ...

) launched a petition campaign calling on President Obama and U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch

Loretta Elizabeth Lynch (born May 21, 1959) is an American lawyer who served as the 83rd attorney general of the United States from 2015 to 2017. She was appointed by President Barack Obama to succeed Eric Holder and previously served as the Un ...

to formally exonerate Ethel Rosenberg. In October 2016, both Michael and Robert Meeropol spoke with Anderson Cooper

Anderson Hays Cooper (born June 3, 1967) is an American broadcast journalist and political commentator from the Vanderbilt family. He is the primary anchor of the CNN news broadcast show ''Anderson Cooper 360°''. In addition to his duties at C ...

in an interview which aired on ''60 Minutes

''60 Minutes'' is an American television news magazine broadcast on the CBS television network. Debuting in 1968, the program was created by Don Hewitt and Bill Leonard, who chose to set it apart from other news programs by using a unique sty ...

''. In January 2017 Senator Elizabeth Warren

Elizabeth Ann Warren (née Herring; born June 22, 1949) is an American politician and former law professor who is the senior United States senator from Massachusetts, serving since 2013. A member of the Democratic Party and regarded as a ...

sent Obama a letter requesting consideration of the exoneration request.

In 2021 Ethel's sons restarted the campaign to pardon Ethel, as they were more optimistic that President Biden will consider this favorably. ''Ethel Rosenberg: A Cold War Tragedy'' by Anne Sebba

Anne Sebba (''née'' Rubinstein, born 1951) is a British biographer, lecturer and journalist. She is the author of nine non-fiction books for adults, two biographies for children, and several introductions to reprinted classics.

Life

Anne Sebba ...

was published by Orion Books

Orion Publishing Group Ltd. is a UK-based book publisher. It was founded in 1991 and acquired Weidenfeld & Nicolson the following year. The group has published numerous bestselling books by notable authors including Ian Rankin, Michael Connelly, ...

on 24 June 2021.

Artistic representations

* The song "Julius and Ethel" written byBob Dylan

Bob Dylan (legally Robert Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter. Often regarded as one of the greatest songwriters of all time, Dylan has been a major figure in popular culture during a career sp ...

in 1983 is based on the Rosenberg case.

* E. L. Doctorow

Edgar Lawrence Doctorow (January 6, 1931 – July 21, 2015) was an American novelist, editor, and professor, best known for his works of historical fiction.

He wrote twelve novels, three volumes of short fiction and a stage drama. They included ...

's 1971 novel '' The Book of Daniel'' is loosely based on the Rosenbergs and their sons' attempt to clear their name. The 1983 film by Sidney Lumet

Sidney Arthur Lumet ( ; June 25, 1924 – April 9, 2011) was an American film director. He was nominated five times for the Academy Award: four for Best Director for '' 12 Angry Men'' (1957), ''Dog Day Afternoon'' (1975), ''Network'' (1976) ...

, ''Daniel

Daniel is a masculine given name and a surname of Hebrew origin. It means "God is my judge"Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 68. (cf. Gabriel—"God is my strength"), ...

'', is in turn based on the novel.

* The main character in Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath (; October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) was an American poet, novelist, and short story writer. She is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry and is best known for two of her published collections, ''The ...

's novel ''The Bell Jar

''The Bell Jar'' is the only novel written by the American writer and poet Sylvia Plath. Originally published under the pseudonym "Victoria Lucas" in 1963, the novel is semi-autobiographical with the names of places and people changed. The book ...

'' is morbidly interested in the Rosenbergs' case.

* Images of the Rosenbergs are engraved on a memorial in Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, Cuba. The accompanying caption says they were murdered.

* The ghost of Ethel appears in the play ''Angels in America

''Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes'' is a two-part play by American playwright Tony Kushner. The work won numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, the Tony Award for Best Play, and the Drama Desk Award for O ...

'', where she haunts attorney Roy Cohn

Roy Marcus Cohn (; February 20, 1927 – August 2, 1986) was an American lawyer and prosecutor who came to prominence for his role as Senator Joseph McCarthy's chief counsel during the Army–McCarthy hearings in 1954, when he assisted McCarth ...

as he dies of AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ma ...

.

* The execution is explored in great detail and serves as the premise of Robert Coover

Robert Lowell Coover (born February 4, 1932) is an American novelist, short story writer, and T.B. Stowell Professor Emeritus in Literary Arts at Brown University. He is generally considered a writer of fabulation and metafiction.

Background

C ...

's 1977 novel ''The Public Burning

''The Public Burning'', Robert Coover's third novel, was published in 1977. It is an account of the events leading to the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. An uncharacteristically human caricature of Richard Nixon serves as protagonist a ...

''.

* Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz

Faiz Ahmad ''Faiz'' (13 February 1911 – 20 November 1984; Urdu, Punjabi:

فیض احمد فیض) was a Pakistani poet, and author of Urdu and Punjabi literature. Faiz was one of the most celebrated Pakistani Urdu writers of his time. Out ...

(1911–1984), renowned for his socialist views, wrote a poem "" (, 'We who were killed in the dark lanes') in tribute to the Rosenbergs. It is considered a classic piece of Urdu literature and part of contemporary folklore and poetic discourses.

* Singer Billy Joel

William Martin Joel (born May 9, 1949) is an American singer, pianist and songwriter. Commonly nicknamed the "Piano Man" after his album and signature song of the same name, he has led a commercially successful career as a solo artist since th ...

mentions the Rosenbergs in the lyrics of his 1989 song "We Didn't Start the Fire

"We Didn't Start the Fire" is a song written and published by American musician Billy Joel. The song was released as a single on September 18, 1989, and later released as part of Joel's album '' Storm Front'' on October 17, 1989. A list song, it ...

".

See also

*Atomic spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early Cold ...

* Soviet atomic bomb project

The Soviet atomic bomb project was the classified research and development program that was authorized by Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union to develop nuclear weapons during and after World War II.

Although the Soviet scientific community di ...

* Capital punishment by the United States federal government

Capital punishment is a legal penalty under the criminal justice system of the United States federal government. It can be imposed for treason, espionage, murder, large-scale drug trafficking, or attempted murder of a witness, juror, or court ...

* List of people executed by the United States federal government

The following is a list of people executed by the United States federal government.

Post-''Gregg'' executions

Sixteen executions (none of them military) have occurred in the modern post-''Gregg'' era. Since 1963, sixteen people have been execut ...

Notes

Works cited

* Feklisov, Aleksandr, and Kostin, Sergei. ''The Man Behind the Rosenbergs''. Enigma Books, 2003. . * Roberts, Sam. ''The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case''. Random House, 2001. . * Schneir, Walter, and Scheir, Miriam. ''Invitation to an Inquest''. Pantheon Books, 1983. . * Schrecker, Ellen. ''Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America''. Little, Brown and Company, 1998. .Further reading

* Sebba, Anne, ''Ethel Rosenberg, A Cold War Tragedy'' (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2021). *Alman, Emily A. and David. ''Exoneration: The Trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell – Prosecutorial deceptions, suborned perjuries, anti-Semitism, and precedent for today's unconstitutional trials''Green Elms Press

2010. * Carmichael, Virginia .''Framing history: the Rosenberg story and the Cold War'', (University of Minnesota Press, 1993) * Clune, Lori. "Great Importance World-Wide: Presidential Decision-Making and the Executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg." ''American Communist History'' 10.3 (2011): 263–284

online

* Doctorow, E. L. ''The Book of Daniel''. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2007. * Deborah Friedell, "How Utterly Depreaved!" (review of

Anne Sebba

Anne Sebba (''née'' Rubinstein, born 1951) is a British biographer, lecturer and journalist. She is the author of nine non-fiction books for adults, two biographies for children, and several introductions to reprinted classics.

Life

Anne Sebba ...

, ''Ethel Rosenberg: A Cold War Tragedy'', Weidenfeld, 2021, , 288 pp.), ''London Review of Books

The ''London Review of Books'' (''LRB'') is a British literary magazine published twice monthly that features articles and essays on fiction and non-fiction subjects, which are usually structured as book reviews.

History

The ''London Review of ...

'', vol. 43, no. 13 (1 July 2021), pp. 11–13

* Goldstein, Alvin H. ''The Unquiet Death of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg'', 1975.

* Harris, Brian. "Injustice", Sutton Publishing. 2006. (An examination of the trial)

* Hornblum, Allen M. ''The Invisible Harry Gold: The Man Who Gave the Soviets the Atom Bomb'', Yale University Press. 2010.

* Meeropol, Michael, " 'A Spy Who Turned His Family In': Revisiting David Greenglass and the Rosenberg Case," ''American Communist History'' (May 2018)

* Meeropol, Michael, ed. ''The Rosenberg Letters: A Complete Edition of the Prison Correspondence of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg''. New York: Garland Publishing

Garland Science was a publishing group that specialized in developing textbooks in a wide range of life sciences subjects, including cell and molecular biology, immunology, protein chemistry, genetics, and bioinformatics. It was a subsidiary of ...

, 1994.

* Meeropol, Robert and Michael Meeropol. ''We Are Your Sons: The Legacy of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg''. University of Illinois Press

The University of Illinois Press (UIP) is an American university press and is part of the University of Illinois system. Founded in 1918, the press publishes some 120 new books each year, plus 33 scholarly journals, and several electronic project ...

, 1986. . Chapter 15 is a detailed refutation of Radosh and Milton's scholarship.

* Meeropol, Robert. ''An Execution in the Family: One Son's Journey''. St. Martin's Press, 2003.

* Nason, Tema. ''Ethel: The Fictional Autobiography of Ethel Rosenberg''. Delacourt, 1990. and by Syracuse, 2002,

*

* Radosh, Ronald and Joyce Milton. ''The Rosenberg File: A Search for the Truth''. Henry Holt (1983). . a standard scholarly history

* Roberts, Sam. ''The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case'', Random House, 2003,

*

* Sam Roberts, ''The Brother: The Untold Story of Atomic Spy David Greenglass and How He Sent His Sister, Ethel Rosenberg, to the Electric Chair'', Random House, 2001.

* Walter Schneir & Miriam Schneir, ''Invitation to an Inquest: Reopening the Rosenberg Case'', 1973.

* Schneir, Walter. ''Final Verdict: What Really Happened in the Rosenberg Case'', Melville House, 2010.

* Trahair, Richard C.S. and Robert Miller. ''Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations.'' Enigma Books, 2009.

* Wexley, John. ''The Judgment of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg''. Ballantine Books