Essex (1799 whaleship) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Essex'' was an American whaling ship from

''Essex'' was attacked approximately west of South America. After spending two days salvaging what supplies they could from the waterlogged wreck, the 20 sailors prepared to set out in the three small whaleboats, aware that they had wholly inadequate supplies of food and fresh water for a journey to land. The boats were rigged with makeshift masts and sails taken from ''Essex'', and boards were added to heighten the

''Essex'' was attacked approximately west of South America. After spending two days salvaging what supplies they could from the waterlogged wreck, the 20 sailors prepared to set out in the three small whaleboats, aware that they had wholly inadequate supplies of food and fresh water for a journey to land. The boats were rigged with makeshift masts and sails taken from ''Essex'', and boards were added to heighten the

Pollard returned to sea in early 1822 to captain the whaleship ''Two Brothers''. She was wrecked on the

Pollard returned to sea in early 1822 to captain the whaleship ''Two Brothers''. She was wrecked on the

Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, which was launched in 1799. In 1820, while at sea in the southern Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

under the command of Captain George Pollard Jr., the ship was attacked and sunk by a sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

. Thousands of miles from the coast of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

with little food and water, the 20-man crew was forced to make for land in the ship's surviving whaleboat

A whaleboat is a type of open boat that was used for catching whales, or a boat of similar design that retained the name when used for a different purpose. Some whaleboats were used from whaling ships. Other whaleboats would operate from the sh ...

s.

The men suffered severe dehydration, starvation, and exposure on the open ocean, and the survivors eventually resorted to eating the bodies of the crewmen who had died. When that proved insufficient, members of the crew drew lots to determine whom they would sacrifice so that the others could live. Seven crew members were cannibalized before the last of the eight survivors were rescued, more than three months after the sinking of the ''Essex''. First mate Owen Chase

Owen may refer to:

Origin: The name Owen is of Irish and Welsh origin.

Its meanings range from noble, youthful, and well-born.

Gender: Owen is historically the masculine form of the name. Popular feminine variations include Eowyn and Owena ...

and cabin boy Thomas Nickerson

Thomas Gibson Nickerson (March 20, 1805 – February 7, 1883) was an American sailor and author. In 1819, when he was fourteen years old, Nickerson served as cabin boy on the whaleship ''Essex''. On this voyage, the ship was sunk by a whale it ...

later wrote accounts of the ordeal. The tragedy attracted international attention, and inspired Herman Melville

Herman Melville ( born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works are '' Moby-Dick'' (1851); '' Typee'' (1846), a ...

to write his famous 1851 novel ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship ''Pequod'', for revenge against Moby Dick, the giant whi ...

''.

Ship and crew

By the time of her fateful voyage, ''Essex'' was already twenty years old, but because so many of her previous voyages had been profitable, she had gained a reputation as a "lucky" vessel. Captain George Pollard Jr. andfirst mate

A chief mate (C/M) or chief officer, usually also synonymous with the first mate or first officer, is a licensed mariner and head of the deck department of a merchant ship. The chief mate is customarily a watchstander and is in charge of the shi ...

Owen Chase

Owen may refer to:

Origin: The name Owen is of Irish and Welsh origin.

Its meanings range from noble, youthful, and well-born.

Gender: Owen is historically the masculine form of the name. Popular feminine variations include Eowyn and Owena ...

had served together on the ship's previous trip, which had been highly successful and led to their promotions. In 1819, at the age of 29, Pollard was one of the youngest men ever to command a whaling ship; Chase was 23, and the youngest member of the crew was the cabin boy, Thomas Nickerson

Thomas Gibson Nickerson (March 20, 1805 – February 7, 1883) was an American sailor and author. In 1819, when he was fourteen years old, Nickerson served as cabin boy on the whaleship ''Essex''. On this voyage, the ship was sunk by a whale it ...

, who was 14. The crew of 21 was mainly white, but a few were free black men.

''Essex'' had recently been totally refitted, but at only in length, and measuring about 239 tons burthen

Builder's Old Measurement (BOM, bm, OM, and o.m.) is the method used in England from approximately 1650 to 1849 for calculating the cargo capacity of a ship. It is a volumetric measurement of cubic capacity. It estimated the tonnage of a ship bas ...

, she was small for a whaleship. ''Essex'' was equipped with four whaleboat

A whaleboat is a type of open boat that was used for catching whales, or a boat of similar design that retained the name when used for a different purpose. Some whaleboats were used from whaling ships. Other whaleboats would operate from the sh ...

s, each about in length, and she had an additional whaleboat below decks.

Final voyage

''Essex'' departed from Nantucket on August 12, 1819, on what was expected to be a roughly two-and-a-half-year voyage to the bountiful whaling grounds off the west coast ofSouth America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

. The crew numbered 21 men in total. Among the sailors, there were seven black men: William Bond, Samuel Reed, Richard Peterson, Henry DeWitt, Lawson Thomas, Charles Shorter and Isaiah Sheppard; four individuals from places other than Nantucket: Seth Weeks, Joseph West, William Wright, and Isaac Cole; and one Englishman named Thomas Chapple. Captain George Pollard, First Mate Owen Chase, Second Mate Matthew Joy, and the rest of the crew, Barzillai Ray, Charles Ramsdell, Benjamin Lawrence and Owen Coffin, and cabin boy Thomas Nickerson, were all from Nantucket.

Two days after her departure from Nantucket, ''Essex'' was hit by a sudden squall

A squall is a sudden, sharp increase in wind speed lasting minutes, as opposed to a wind gust, which lasts for only seconds. They are usually associated with active weather, such as rain showers, thunderstorms, or heavy snow. Squalls refer to the ...

in the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension the North Atlantic Drift, is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the Unit ...

. She was knocked on her beam-ends and nearly sank. She lost her topgallant sail and two whaleboats were destroyed, with an additional whaleboat damaged. Captain Pollard elected to continue the voyage without replacing the two boats or repairing the damage.

''Essex'' rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

in January 1820 after a transit of five weeks, which was extremely slow. With this and the unsettling earlier incident, the crew began to talk of ill omens. Their spirits were temporarily lifted when ''Essex'' began the long spring and summer hunt in the warm waters of the South Pacific Ocean

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

, traveling north along the western coast of South America up to Atacames

Atacames is a beach town located on Ecuador's Northern Pacific coast. It is located in the province of Esmeraldas, approximately 30 kilometers south west from the capital of that province, which is also called Esmeraldas. In 2005 Atacames's popul ...

, in what was then the Spanish-ruled territory of the Royal Audience of Quito (present-day Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

).

Whaling grounds depleted

The crew was divided into three groups of six, each of which manned one of the three usable whaleboats whenever whales were sighted; the remaining three men stayed aboard to manage ''Essex''. Each whaleboat was led by one of the three officers – Pollard, Chase, and Joy – each of whom then chose his five other crew members. In September 1820, a sailor named Henry DeWitt deserted at Atacames, reducing the crew of ''Essex'' to 20 men. While sailors fled whaling ships all the time, the desertion was bad news for Captain Pollard because each of the ship's three whaleboats required a crew of six. This meant only two men would remain to keep ''Essex'' while a whale-hunt was in progress, which was not sufficient to safely handle a ship of ''Essex''s size and type. After finding the area's population of whales exhausted, the crew encountered other whalers who told them of a vast newly discovered hunting ground, known as the "offshore ground", located between 5 and 10 degrees south latitude and between 105 and 125 degrees west longitude, about to the south and west. This was an immense distance from known shores for the whalers, and the crew had heard rumors thatcannibal

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, bo ...

s populated the many islands of the South Pacific.

Repairs and resupply at Galápagos

To restock their food supplies for the long journey, ''Essex'' sailed for Charles Island (later renamedFloreana Island

Floreana Island ( Spanish: ''Isla Floreana'') is an island of the Galápagos Islands. It was named after Juan José Flores, the first president of Ecuador, during whose administration the government of Ecuador took possession of the archipelag ...

) in the Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands ( Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuad ...

. The crew needed to fix a serious leak and initially anchored off Hood Island (now known as Española Island

Española Island (Spanish: ''Isla Española'') is part of the Galápagos Islands. The English named it ''Hood Island'' after Viscount Samuel Hood. It is located in the extreme southeast of the archipelago and is considered, along with Sant ...

) on October 8, 1820. During a week at anchor, they captured 300 Galápagos giant tortoises to supplement the ship's food stores. They then sailed for Charles Island, where on October 22 they took another 60 tortoises. The tortoises weighed between each. The sailors captured them alive and allowed some of them to roam the ship at will; the rest they kept in the hold. They believed the tortoises were capable of living for a year without eating or drinking water (though in fact the tortoises slowly starved). The sailors considered the tortoises delicious and extremely nutritious, and planned to butcher them at sea as needed.

While hunting on Charles Island, helmsman Thomas Chapple decided to set a fire as a prank. It was the height of the dry season, and the fire quickly burned out of control, surrounding the hunters and forcing them to run through the flames to escape. By the time the men returned to ''Essex'', almost the entire island was burning. The crew was upset about the fire, and Captain Pollard swore vengeance on whoever had set it. The next day, the island was still burning as the ship sailed for the offshore grounds. After a full day of sailing, the fire was still visible on the horizon. Fearing a certain whipping, Chapple only later admitted that he had set the fire.

Many years later, Nickerson returned to Charles Island and found a blackened wasteland; he observed "neither trees, shrubbery, nor grass have since appeared". It has been suggested that the fire contributed to the near-extinction of the Floreana Island tortoise

Floreana Island (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Isla Floreana'') is an island of the Galápagos Islands. It was named after Juan José Flores, the first President (government title), president of Ecuador, during whose administration the governmen ...

and the Floreana mockingbird, which no longer inhabit the island.

Offshore ground

When ''Essex'' finally reached the promised fishing grounds thousands of miles west of the coast of South America, the crew was unable to find any whales for days. Tension mounted among the officers of ''Essex'', especially between Pollard and Chase. When they finally found a whale on November 16, it surfaced directly beneath Chase's boat, with the result that the boat was "dashed ... literally in pieces". At eight in the morning of November 20, 1820, the lookout sighted spouts, and the three remaining whaleboats set out to pursue a pod of sperm whales. On theleeward

Windward () and leeward () are terms used to describe the direction of the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e. towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point of reference ...

side of ''Essex'', Chase's whaleboat harpooned a whale, but its tail struck the boat and opened up a seam, forcing the crew to cut the harpoon line and return to ''Essex'' for repairs. Two miles away off the windward

Windward () and leeward () are terms used to describe the direction of the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e. towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point of reference ...

side, Pollard's and Joy's boats each harpooned a whale and were dragged towards the horizon away from ''Essex'' in what whalers called a "Nantucket sleighride

A Nantucket sleighride is the dragging of a whaleboat by a harpooned whale while whaling. It is an archaic term from the early days of open-boat whaling, when the animals were harpooned from small open boats. Once harpooned, the whale, in pa ...

".

Whale attack

Chase was repairing the damaged whaleboat on board ''Essex'' when the crew sighted an abnormally large sperm whale bull (reportedly around in length) acting strangely. It lay motionless on the surface facing the ship and then began to swim towards the vessel, picking up speed by shallow diving. The whale rammed ''Essex'', rocking her from side to side, and then dove under her, surfacing close on the ship'sstarboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which ar ...

side. As its head lay alongside the bow and the tail

The tail is the section at the rear end of certain kinds of animals’ bodies; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage to the torso. It is the part of the body that corresponds roughly to the sacrum and coccyx in mammal ...

by the stern, it was motionless and appeared to be stunned. Chase prepared to harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target ani ...

it from the deck when he realized that its tail was only inches from the rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adve ...

, which the whale could easily destroy if provoked by an attempt to kill it. Fearing to leave the ship stuck thousands of miles from land with no way to steer it, Chase hesitated. The whale recovered, swam several hundred yards forward of the ship, and turned to face the ship's bow.

The whale crushed the bow, driving the vessel backwards, and then finally disengaged its head from the shattered timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, w ...

s and swam off, never to be seen again, leaving ''Essex'' quickly going down by the bow. Chase and the remaining sailors frantically tried to add rigging

Rigging comprises the system of ropes, cables and chains, which support a sailing ship or sail boat's masts—''standing rigging'', including shrouds and stays—and which adjust the position of the vessel's sails and spars to which they ar ...

to the only remaining whaleboat, while the steward William Bond ran below to gather the captain's sea chest and whatever navigational aids he could find.

The cause of the whale's aggression is not known. In ''In the Heart of the Sea'', author Nathaniel Philbrick speculated that it may have first struck the boat accidentally, or have had its curiosity aroused by the sound of a hammer as a whaler worked to repair a damaged whaleboat by nailing in a replacement board. The frequency and sound of the nailing may have sounded similar to those made by bull sperm whales to communicate and echolocate.

Survivors

''Essex'' was attacked approximately west of South America. After spending two days salvaging what supplies they could from the waterlogged wreck, the 20 sailors prepared to set out in the three small whaleboats, aware that they had wholly inadequate supplies of food and fresh water for a journey to land. The boats were rigged with makeshift masts and sails taken from ''Essex'', and boards were added to heighten the

''Essex'' was attacked approximately west of South America. After spending two days salvaging what supplies they could from the waterlogged wreck, the 20 sailors prepared to set out in the three small whaleboats, aware that they had wholly inadequate supplies of food and fresh water for a journey to land. The boats were rigged with makeshift masts and sails taken from ''Essex'', and boards were added to heighten the gunwale

The gunwale () is the top edge of the hull of a ship or boat.

Originally the structure was the "gun wale" on a sailing warship, a horizontal reinforcing band added at and above the level of a gun deck to offset the stresses created by firi ...

s and prevent large waves from spilling over the sides. Inside Pollard's sea chest, which Bond's quick thinking had managed to save, were two sets of navigational equipment and two copies of maritime charts. These were split between Pollard's and Chase's boats; Joy's boat was left without any means of navigating except to keep within sight of the other boats.

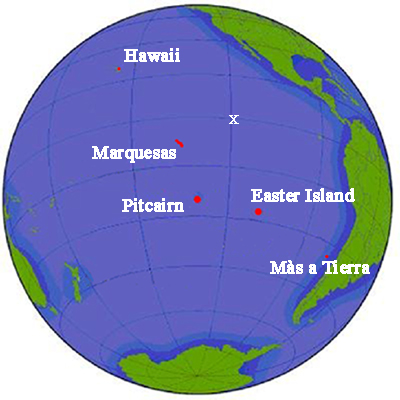

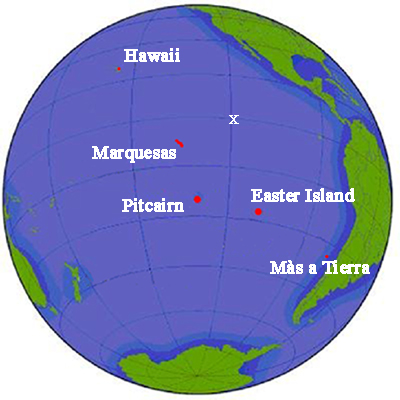

Examining the charts, the officers deduced that the closest known islands, the Marquesas

The Marquesas Islands (; french: Îles Marquises or ' or '; Marquesan: ' (North Marquesan) and ' (South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in t ...

, were more than to the west, and Captain Pollard intended to make for them, but the crew, led by Chase, voiced their fears that the islands might be inhabited by cannibals and voted to sail east instead for South America. Unable to sail against the trade wind

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisph ...

s, the boats would first need to sail south for before they could take advantage of the Westerlies

The westerlies, anti-trades, or prevailing westerlies, are prevailing winds from the west toward the east in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude. They originate from the high-pressure areas in the horse latitudes and tren ...

to turn towards South America, which then would still lie another to the east. Even with the knowledge that this route would require them to travel twice as far as the route to the Marquesas, Pollard acceded to the crew's decision and the boats set their course due south.

Food and water were rationed from the beginning, but most of the food had been soaked in seawater. The men ate this food first even though it increased their thirst. It took them around two weeks to consume the contaminated food, and by this time the survivors were rinsing their mouths with seawater and drinking their own urine. Several of the giant tortoises captured from the Galápagos had been brought aboard the whaleboats as well, but their size prevented the crew from bringing all of them.

Never designed for long voyages, all the whaleboats had been very roughly repaired, and leaks were a constant and serious problem during the voyage. After losing a timber, the crew of one boat had to lean to one side to raise the other side out of the water until another boat was able to draw close, allowing a sailor to nail a piece of wood over the hole. Storms and rough seas frequently plagued the tiny whaleboats, and the men who were not occupied with steering and trimming the sails spent most of their time bailing water from the bilge.

Landfall

On December 20, exactly one month after the whale attack, and within hours of the crew beginning to die of thirst, the boats landed on uninhabited Henderson Island, a small uplifted coral atoll within the modern-day British territory of thePitcairn Islands

The Pitcairn Islands (; Pitkern: '), officially the Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands, is a group of four volcanic islands in the southern Pacific Ocean that form the sole British Overseas Territory in the Pacific Ocean. The four is ...

. The men incorrectly believed that they had landed on Ducie Island

Ducie Island is an uninhabited atoll in the Pitcairn Islands. It lies east of Pitcairn Island, and east of Henderson Island, and has a total area of , which includes the lagoon. It is long, measured northeast to southwest, and about wide. ...

, a similar atoll to the east. Had they landed on Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

itself, to the southwest, they might have received help; the descendants of the survivors of HMS ''Bounty'', who had famously mutinied in 1789, still lived there.

On Henderson Island, ''Essex''s crew found a small freshwater spring below the tideline and the starving men gorged themselves on endemic birds, crabs, eggs, and peppergrass

''Lepidium'' is a genus of plants in the mustard/cabbage family, Brassicaceae. The genus is widely distributed in the Americas, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Australia.Lloyd's List

''Lloyd's List'' is one of the world's oldest continuously running journals, having provided weekly shipping news in London as early as 1734. It was published daily until 2013 (when the final print issue, number 60,850, was published), and is ...

'' reported that ''Surry'' had rescued the three men and taken them to Port Jackson

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman S ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

.

Separation

The remaining ''Essex'' crewmen, now numbering 17 in 3 boats, resumed the journey on December 27 with the intention of reachingEaster Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

. Within three days they had exhausted the crabs and birds they had stockpiled from Henderson in preparation for the voyage, leaving only a small reserve of the bread previously salvaged from ''Essex''. On January 4, 1821, they estimated that they had drifted too far south of Easter Island to reach it and decided to make for Más a Tierra island instead, to the east and west of South America. One by one, the men began to die.

Second mate Matthew Joy, whose health had been poor even before ''Essex'' left Nantucket, was dying; as his condition steadily worsened, Joy asked if he could rest on Pollard's boat until his death. On January 10, Joy became the first crew member to die, and Nantucketer Obed Hendricks assumed the leadership of Joy's boat.

The following day, Chase's whaleboat, which also carried Richard Peterson, Isaac Cole, Benjamin Lawrence, and Thomas Nickerson, became separated from the others during a squall

A squall is a sudden, sharp increase in wind speed lasting minutes, as opposed to a wind gust, which lasts for only seconds. They are usually associated with active weather, such as rain showers, thunderstorms, or heavy snow. Squalls refer to the ...

. Peterson, the oldest crew member, lost the will to live and died on January 18. As with Joy, he was sewn into his clothes and buried at sea, as was the custom. On February 8 Isaac Cole died, but with food running out the survivors kept his body, and after a discussion, the men resorted to cannibalism. They ate his liver and kidneys but struggled to eat the sinewy flesh.

Hendricks' boat, carrying crew members William Bond, Lawson Thomas, Charles Shorter, Isaiah Sheppard, and Joseph West, exhausted its food supplies on January 14, and Pollard offered to share his own boat's remaining provisions. Pollard's boat carried Samuel Reed, Owen Coffin, Barzillai Ray, and Charles Ramsdell. They ran out of food on January 21. Thomas died on January 20, and the others decided they had no choice but to keep the body for food. Shorter died on January 23, Sheppard on January 27, and Reed on January 28.

Later that day, the two boats separated; Hendricks' boat was never seen again. All three men are presumed to have died at sea. A whaleboat was later found washed up on Ducie Island

Ducie Island is an uninhabited atoll in the Pitcairn Islands. It lies east of Pitcairn Island, and east of Henderson Island, and has a total area of , which includes the lagoon. It is long, measured northeast to southwest, and about wide. ...

with the skeletons of three people inside. Although it was suspected to be Obed Hendricks' missing boat, and the remains those of Hendricks, Bond, and West, the remains have never been positively identified.

By February 1, the food on Pollard's boat was again exhausted and the survivors' situation became dire. The men drew lots to determine who would be sacrificed for the survival of the remainder. A young man named Owen Coffin

Owen Coffin (August 24, 1802 – February 2, 1821) was a sailor aboard the Nantucket whaler ''Essex'' when it set sail for the Pacific Ocean on a sperm whale-hunting expedition in August 1819, under the command of his cousin, George Pollard, J ...

, Captain Pollard's 18-year-old first cousin, whom he had sworn to protect, drew the black spot. Pollard allegedly offered to protect his cousin, but Coffin is said to have replied: "No, I like my lot as well as any other". Lots were drawn again to determine who would be Coffin's executioner. His young friend, Charles Ramsdell, drew the black spot. Ramsdell shot Coffin; Ramsdell, Pollard, and Barzillai Ray consumed the body.

On February 11, Ray also died. For the remainder of their journey, Pollard and Ramsdell survived by gnawing on Coffin's and Ray's bones.

Rescue and reunion

By February 15, the three survivors of Chase's whaleboat had again run out of food. On February 18 – 89 days after ''Essex'' sank – off the coast ofChile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

the British vessel spotted and rescued Chase, Lawrence, and Nickerson. Several days after the rescue, the empty whaleboat was lost in a storm while under tow behind ''Indian''. Pollard's boat, now containing only Pollard and Ramsdell, was rescued when almost within sight of the South American coast by the Nantucket whaleship ''Dauphin'', 93 days after ''Essex'' sank, on February 23. Pollard and Ramsdell by that time were so completely dissociative

Dissociatives, colloquially dissos, are a subclass of hallucinogens which distort perception of sight and sound and produce feelings of detachment – dissociation – from the environment and/or self. Although many kinds of drugs are capable of ...

that they did not even notice ''Dauphin'' alongside them, and became terrified when they saw their rescuers. On March 5, ''Dauphin'' encountered , which was sailing to Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

, and transferred the two men to her.

After a few days in Valparaíso, Chase, Lawrence, and Nickerson were transferred to the frigate and placed under the care of the ship's doctor, who oversaw their recovery. After officials were informed that three ''Essex'' survivors – Wright, Weeks, and Chapple – had been left behind on Ducie Island (they were actually left on Henderson Island), the authorities asked the merchant vessel ''Surry'', which already intended to sail across the Pacific, to look for the men. The rescue succeeded. On March 17, Pollard and Ramsdell were reunited with Chase, Lawrence, and Nickerson. By the time the last of the eight survivors were rescued on April 5, 1821, the corpses of seven fellow sailors had been consumed. All eight went to sea again within months of their return to Nantucket. Herman Melville

Herman Melville ( born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works are '' Moby-Dick'' (1851); '' Typee'' (1846), a ...

later speculated that all would have survived had they followed Captain Pollard's recommendation and sailed to Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

.

Aftermath

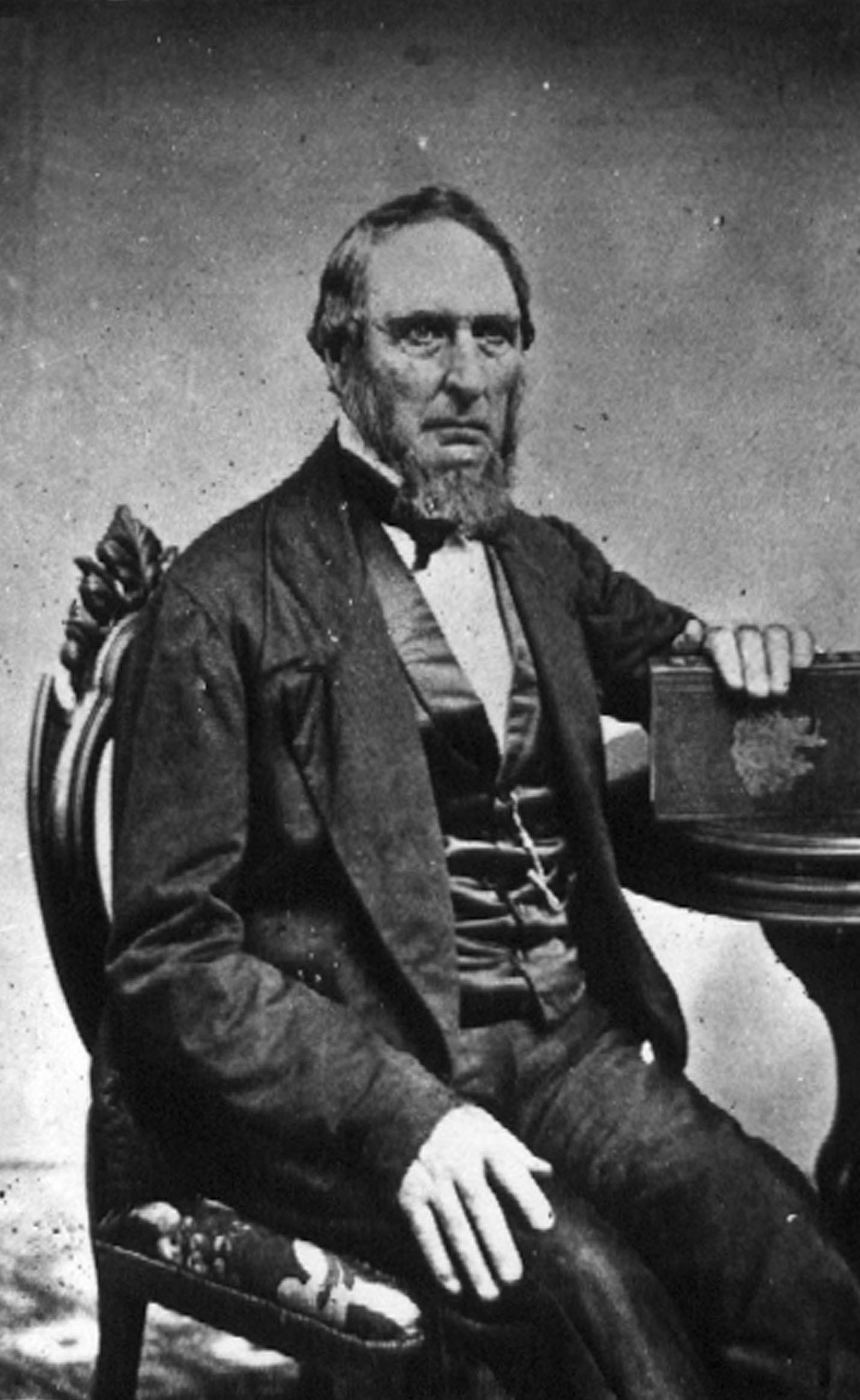

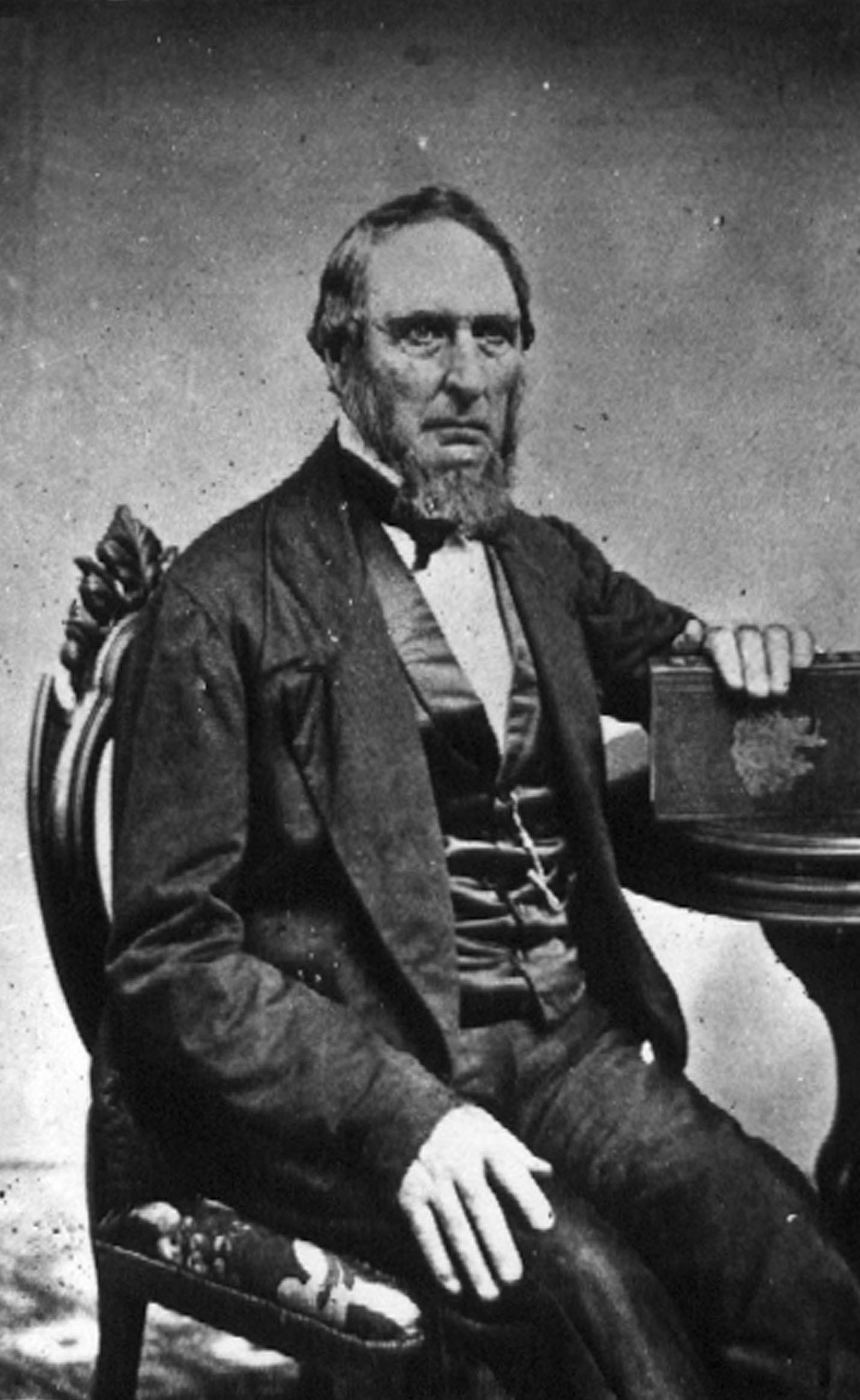

Pollard returned to sea in early 1822 to captain the whaleship ''Two Brothers''. She was wrecked on the

Pollard returned to sea in early 1822 to captain the whaleship ''Two Brothers''. She was wrecked on the French Frigate Shoals

The French Frigate Shoals ( Hawaiian: Kānemilohai) is the largest atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Its name commemorates French explorer Jean-François de La Pérouse, who nearly lost two frigates when attempting to navigate the sh ...

during a storm off the coast of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

on his first voyage, after which he joined a merchant vessel, which was wrecked off the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost ...

) shortly thereafter. By now Pollard was considered a "Jonah" (unlucky), and no ship owner would trust him to sail on a ship again, so he was forced to retire. He subsequently became Nantucket's night watchman. Every November 20, he would reportedly lock himself in his room and fast

Fast or FAST may refer to:

* Fast (noun), high speed or velocity

* Fast (noun, verb), to practice fasting, abstaining from food and/or water for a certain period of time

Acronyms and coded Computing and software

* ''Faceted Application of Subje ...

in memory of the men of ''Essex''. He died in Nantucket on January 7, 1870, aged 78.

First Mate Owen Chase

Owen may refer to:

Origin: The name Owen is of Irish and Welsh origin.

Its meanings range from noble, youthful, and well-born.

Gender: Owen is historically the masculine form of the name. Popular feminine variations include Eowyn and Owena ...

returned to Nantucket on June 11, 1821, to find he had a 14-month-old daughter he had never met. Four months later he had completed an account of the disaster, the ''Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex''; Herman Melville

Herman Melville ( born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works are '' Moby-Dick'' (1851); '' Typee'' (1846), a ...

used it as one of the inspirations for his novel ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship ''Pequod'', for revenge against Moby Dick, the giant whi ...

'' (1851). In December, Chase sailed as first mate on the whaler ''Florida'', and then as captain of ''Winslow'' for each subsequent voyage, until he could afford to build his own whaler, ''Charles Carrol''. Chase remained at sea for 19 years, only returning home for short periods every two or three years, each time fathering a child. His first two wives died while he was at sea. He divorced his third wife when he found she had given birth 16 months after he had last seen her, although he subsequently brought up the child as his own. In September 1840, two months after the divorce was finalized, he married for the fourth and final time and retired from whaling. Memories of the harrowing ordeal on ''Essex'' haunted Chase, and he suffered terrible headaches and nightmares. Later in his life, he began hiding food in the attic of his Nantucket house on Orange Street and was eventually institutionalized. He died in Nantucket on March 7, 1869, aged 73.

The cabin boy, Thomas Nickerson

Thomas Gibson Nickerson (March 20, 1805 – February 7, 1883) was an American sailor and author. In 1819, when he was fourteen years old, Nickerson served as cabin boy on the whaleship ''Essex''. On this voyage, the ship was sunk by a whale it ...

, became a captain in the Merchant Service and late in his life wrote his own account of the sinking, titled ''The Loss of the Ship "Essex" Sunk by a Whale and the Ordeal of the Crew in Open Boats''. Nickerson wrote this account 56 years after the sinking, in 1876, and it was lost until 1960; the Nantucket Historical Association

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

published it in 1984. He died in February 1883, aged 77.

The other surviving crew members met various fates:

*Thomas Chapple died of plague fever in Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western part. The Indonesian part, ...

, while working as a missionary.

*William Wright was lost in a hurricane in the West Indies.

*Charles Ramsdell died in Nantucket on July 8, 1866, aged 62.

*Benjamin Lawrence died in Nantucket on March 28, 1879, aged 80.

*Seth Weeks died in Barnstable County, Massachusetts

Barnstable County is a county located in the U.S. state of Massachusetts. At the 2020 census, the population was 228,996. Its shire town is Barnstable. The county consists of Cape Cod and associated islands (some adjacent islands are in D ...

, on September 12, 1887, the last of the ''Essex'' survivors to die.

Cultural works

As well as inspiring much of American authorHerman Melville

Herman Melville ( born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works are '' Moby-Dick'' (1851); '' Typee'' (1846), a ...

's classic 1851 novel ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship ''Pequod'', for revenge against Moby Dick, the giant whi ...

'', the story of the ''Essex'' tragedy has been dramatized in film, television, and music:

* The dramatized documentary '' Revenge of the Whale'' (2001), was produced and broadcast on September 7, 2001, by NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

.

* Composer Deirdre Gribbin's 2004 string quartet ''What the Whaleship Saw'' was inspired by the event.

* The television movie ''The Whale

A whale is a sea mammal.

Whale or The Whale may also refer to:

Places Extraterrestrial

* Cetus, a constellation also known as "The Whale"

* Cthulhu Regio on Pluto, unofficially called Whale

United Kingdom

* Whale, Cumbria, England, a hamlet

...

'' (2013) was broadcast on BBC One

BBC One is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's flagship network and is known for broadcasting mainstream programming, which includes BBC News television bulletins, ...

on December 22, wherein an elderly Thomas Nickerson (played by Martin Sheen

Ramón Antonio Gerardo Estévez (born August 3, 1940), known professionally as Martin Sheen, is an American actor. He first became known for his roles in the films ''The Subject Was Roses'' (1968) and ''Badlands'' (1973), and later achieved wid ...

) recounted the events of ''Essex''. Charles Furness

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

played the younger Nickerson, Jonas Armstrong

William Jonas Armstrong is an Irish actor known for playing the title role in the BBC One drama series ''Robin Hood''.

Career

In 2003, Armstrong appeared in ''Quartermaine's Terms'' at the Royal Theatre in Northampton as Derek Meadle. In 2004 ...

played Owen Chase, and Adam Rayner

Adam Chance Abbs Rayner (born 28 August 1977) is an English actor. He is known for television roles including: Dominic Montgomery in '' Mistresses'', Dr. Steve Shaw in '' Hawthorne'', Aidan Marsh in '' Hunted'', Bassam "Barry" Al-Fayeed in ''Tyr ...

played Captain Pollard.

* The 2015 film ''In The Heart of the Sea

''In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex'' is a book by American writer Nathaniel Philbrick about the loss of the whaler ''Essex'' in the Pacific Ocean in 1820. The book was published by Viking Press on May 8, 2000, and won ...

'', directed by Ron Howard

Ronald William Howard (born March 1, 1954) is an American director, producer, screenwriter, and actor. He first came to prominence as a child actor, guest-starring in several television series, including an episode of '' The Twilight Zone''. ...

, was based on Philbrick's book. Chris Hemsworth

Christopher Hemsworth (born 11 August 1983) is an Australian actor. He rose to prominence playing Kim Hyde in the Australian television series ''Home and Away'' (2004–2007) before beginning a film career in Hollywood. In the Marvel Cinemat ...

starred as Owen Chase and Benjamin Walker as Captain Pollard. Brendan Gleeson

Brendan Gleeson (born 29 March 1955) is an Irish actor and film director. He is the recipient of three IFTA Awards, two British Independent Film Awards, and a Primetime Emmy Award and has been nominated twice for a BAFTA Award and four times fo ...

and Tom Holland portrayed the elder and younger Nickerson, respectively.

* German funeral doom band Ahab

Ahab (; akk, 𒀀𒄩𒀊𒁍 ''Aḫâbbu'' 'a-ḫa-ab-bu'' grc-koi, Ἀχαάβ ''Achaáb''; la, Achab) was the seventh king of Israel, the son and successor of King Omri and the husband of Jezebel of Sidon, according to the Hebrew Bib ...

's second full length album, '' The Divinity of Oceans'', is a concept album based on the events of the ''Essex''. Several song titles are drawn directly from the event, such as "Gnawing Bones (Coffin's Lot)" and "Nickerson's Theme".

* The 2016 video game ''Tharsis

Tharsis () is a vast volcanic plateau centered near the equator in the western hemisphere of Mars. The region is home to the largest volcanoes in the Solar System, including the three enormous shield volcanoes Arsia Mons, Pavonis Mons, and As ...

'' was directly inspired by the events of the ''Essex'', featuring a similar situation in a science fiction setting, where members of an unexpectedly crippled Mars mission

Mars mission may refer to:

Space missions

* Exploration of Mars, or any mission to assist in this endeavour

** List of missions to Mars

*** List of Mars orbiters

**** Mars Orbiter Mission, India's first interplanetary mission

*** Mars rover miss ...

can choose to use cannibalism as a last resort.

* American songwriter and YouTuber Rusty Cage dramatized the story of the ''Essex'' in the song "The Final Voyage of the Wailer's Essex", from his 2018 album ''Gangstalkers, Vol. 4''. The song is sung from the perspective of first mate Owen Chase, and ends with the men drawing "bits of paper" from a cap to see who would first be cannibalized.

Other ships attacked by whales

''Essex'' is not the only ship known to have been attacked by a whale: *In 1835, ''Pusie Hall'' was attacked. *In 1836, whales attacked ''Lydia'' and ''Two Generals''. *In 1850, a whale sank ''Pocahontas''. *On August 20, 1851, a whale sank '' Ann Alexander''. *In 1852, a whale sank ''Crusader''. *In 1855, a whale sank ''Waterloo''. *On June 15, 1972, a pod ofkiller whale

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white pat ...

s sank the schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

'' Lucette''.

*On July 7, 1999, a humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh up to . The hu ...

sank the , 111-year-old Herreshoff-designed ''Merlin'' in Whale Bay, Baranof Island

Baranof Island is an island in the northern Alexander Archipelago in the Alaska Panhandle, in Alaska. The name Baranof was given in 1805 by Imperial Russian Navy captain U. F. Lisianski to honor Alexander Andreyevich Baranov. It was called Sh ...

, Alaska.

See also

*Alexander Pearce

Alexander Pearce (1790 – 19 July 1824) was an Irish convict who was transported to the penal colony in Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania), Australia for seven years for theft. He escaped from prison several times, allegedly becoming a cannibal ...

*Custom of the sea

A custom of the sea is a custom that is said to be practiced by the officers and crew of ships and boats in the open sea, as distinguished from maritime law, which is a distinct and coherent body of law that governs maritime questions and offenses ...

, a set of customs practiced by the officers and crew of ships and boats in the open sea, which includes a discussion of cannibalism out of necessity

*''R v Dudley and Stephens

''R v Dudley and Stephens'' (188414 QBD 273, DCis a leading English criminal case which established a precedent throughout the common law world that necessity is not a defence to a charge of murder. The case concerned survival cannibalism foll ...

'' (1884), a case involving cannibalism out of necessity

*Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571

The Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 was a chartered flight from Montevideo, Uruguay, bound for Santiago, Chile, that crashed in the Andes mountains on October 13, 1972. The accident and subsequent survival became known as the Andes flight disast ...

*Donner Party

The Donner Party, sometimes called the Donner–Reed Party, was a group of American pioneers who migrated to California in a wagon train from the Midwest. Delayed by a multitude of mishaps, they spent the winter of 1846–1847 snowbound in th ...

* The French frigate ''Méduse''

General

*List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea

Throughout history, people have mysteriously disappeared at sea, many on voyages aboard floating vessels or traveling via aircraft. The following is a list of known individuals who have mysteriously vanished in open waters, and whose whereabouts r ...

References

Sources

* republished in 1965 as * * **See also '' In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex''Further reading

* *External links

* * {{coord, 0, 41, S, 118, 00, W, display=title, type:waterbody_source:dewiki 1799 ships 1820s missing person cases Formerly missing people Full-rigged ships Herman Melville Incidents of cannibalism Maritime incidents in November 1820 Ships built in Amesbury, Massachusetts Shipwrecks in the Pacific Ocean Tall ships of the United States Whale collisions with ships Whaling ships