Equal Protection Clause on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the

Though equality under the law is an American legal tradition arguably dating to the Declaration of Independence, formal equality for many groups remained elusive. Before passage of the Reconstruction Amendments, which included the Equal Protection Clause, American law did not extend constitutional rights to black Americans. Black people were considered inferior to white Americans, and subject to chattel slavery in the slave states until the

Though equality under the law is an American legal tradition arguably dating to the Declaration of Independence, formal equality for many groups remained elusive. Before passage of the Reconstruction Amendments, which included the Equal Protection Clause, American law did not extend constitutional rights to black Americans. Black people were considered inferior to white Americans, and subject to chattel slavery in the slave states until the

Clio and the Court: An Illicit Love Affair

, ''The Supreme Court Review'' at p. 148 (1965) reprinted in ''The Supreme Court in and of the Stream of Power'' (Kermit Hall ed., Psychology Press 2000). Bingham said about this version: "It confers upon Congress power to see to it that the protection given by the laws of the States shall be equal in respect to life and liberty and property to all persons." The main opponent of the first version was Congressman Robert S. Hale of New York, despite Bingham's public assurances that "under no possible interpretation can it ever be made to operate in the State of New York while she occupies her present proud position." Hale ended up voting for the final version, however. When Senator

Four of the original thirteen states never passed any laws barring interracial marriage, and the other states were divided on the issue in the Reconstruction era. In 1872, the

Four of the original thirteen states never passed any laws barring interracial marriage, and the other states were divided on the issue in the Reconstruction era. In 1872, the

Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877

', pp. 321–322 (HarperCollins 2002). However, some states (e.g. New York) gave local districts discretion to set up schools that were deemed separate but equal. Bickel, Alexander.

The Original Understanding and the Segregation Decision

, ''

Partly because of that enigmatic phrase, but mostly because of self-declared " massive resistance" in the South to the desegregation decision, integration did not begin in any significant way until the mid-1960s and then only to a small degree. In fact, much of the integration in the 1960s happened in response not to ''Brown'' but to the

Partly because of that enigmatic phrase, but mostly because of self-declared " massive resistance" in the South to the desegregation decision, integration did not begin in any significant way until the mid-1960s and then only to a small degree. In fact, much of the integration in the 1960s happened in response not to ''Brown'' but to the

Between the Tiers: The New(est) Equal Protection and Bush v. Gore

", ''University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law'', Vol. 4, p. 372 (2002) . but that assertion is disputed. Whatever its precise origins, the basic idea of the modern approach is that more judicial scrutiny is triggered by purported discrimination that involves " fundamental rights" (such as the right to procreation), and similarly more judicial scrutiny is also triggered if the purported victim of discrimination has been targeted because he or she belongs to a "

'There is Only One Equal Protection Clause': An Appreciation of Justice Stevens's Equal Protection Jurisprudence

, ''Fordham Law Review'', Vol. 74, p. 2301, 2306 (2006). The whole tiered strategy developed by the Court is meant to reconcile the principle of equal protection with the reality that most laws necessarily discriminate in some way. Choosing the standard of scrutiny can determine the outcome of a case, and the strict scrutiny standard is often described as "strict in theory and fatal in fact". In order to select the correct level of scrutiny, Justice

The Supreme Court ruled in ''

The Supreme Court ruled in ''

Original Meaning of Equal Protection of the Laws

, Federalist Blog

Equal Protection: An Overview

Cornell Law School

Equal Protection

Heritage Guide to the Constitution

Equal Protection (U.S. law)

Encyclopædia Britannica * Naderi, Siavash.

The Not So Definite Article

, ''Brown Political Review'' (November 16, 2012). {{US14thAmendment Clauses of the United States Constitution Egalitarianism Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution History of voting rights in the United States

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Often considered as one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses citizenship rights and ...

. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "''nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.''" It mandates that individuals in similar situations be treated equally by the law.

A primary motivation for this clause was to validate the equality provisions contained in the Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Ame ...

, which guaranteed that all citizens would have the guaranteed right to equal protection by law. As a whole, the Fourteenth Amendment marked a large shift in American constitutionalism, by applying substantially more constitutional restrictions against the states than had applied before the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

.

The meaning of the Equal Protection Clause has been the subject of much debate, and inspired the well-known phrase " Equal Justice Under Law". This clause was the basis for '' Brown v. Board of Education'' (1954), the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

decision that helped to dismantle racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

. The clause has also been the basis for '' Obergefell v. Hodges'' which legalized same-sex marriages, along with many other decisions rejecting discrimination against, and bigotry towards, people belonging to various groups.

While the Equal Protection Clause itself applies only to state and local governments, the Supreme Court held in '' Bolling v. Sharpe'' (1954) that the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment nonetheless imposes various equal protection requirements on the federal government via reverse incorporation.

Text

The Equal Protection Clause is located at the end of Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment:Background

Though equality under the law is an American legal tradition arguably dating to the Declaration of Independence, formal equality for many groups remained elusive. Before passage of the Reconstruction Amendments, which included the Equal Protection Clause, American law did not extend constitutional rights to black Americans. Black people were considered inferior to white Americans, and subject to chattel slavery in the slave states until the

Though equality under the law is an American legal tradition arguably dating to the Declaration of Independence, formal equality for many groups remained elusive. Before passage of the Reconstruction Amendments, which included the Equal Protection Clause, American law did not extend constitutional rights to black Americans. Black people were considered inferior to white Americans, and subject to chattel slavery in the slave states until the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

and the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Even black Americans that were not enslaved lacked many crucial legal protections. In the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, the Supreme Court rejected abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

and determined black men, whether free or in bondage, had no legal rights under the U.S. Constitution at the time. Currently, a plurality of historians believe that this judicial decision set the United States on the path to the Civil War, which led to the ratifications of the Reconstruction Amendments.

Before and during the Civil War, the Southern states prohibited speech of pro-Union citizens, anti-slavery advocates, and northerners in general, since the Bill of Rights did not apply to the states during such times. During the Civil War, many of the Southern states stripped the state citizenship of many whites and banished them from their state, effectively seizing their property.

Shortly after the Union victory in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, the Thirteenth Amendment was proposed by Congress and ratified by the states in 1865, abolishing slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Subsequently, many ex- Confederate states then adopted Black Codes

The Black Codes, sometimes called the Black Laws, were laws which governed the conduct of African Americans (free and freed blacks). In 1832, James Kent wrote that "in most of the United States, there is a distinction in respect to political p ...

following the war, with these laws severely restricting the rights of blacks to hold property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

, including real property

In English common law, real property, real estate, immovable property or, solely in the US and Canada, realty, is land which is the property of some person and all structures (also called improvements or fixtures) integrated with or aff ...

(such as real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more genera ...

), and many forms of personal property

property is property that is movable. In common law systems, personal property may also be called chattels or personalty. In civil law systems, personal property is often called movable property or movables—any property that can be moved fr ...

, and to form legally enforceable contracts. Such codes also established harsher criminal consequences for blacks than for whites.

Because of the inequality imposed by Black Codes, a Republican-controlled Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Ame ...

. The Act provided that all persons born in the United States were citizens (contrary to the Supreme Court's 1857 decision in '' Dred Scott v. Sandford''), and required that "citizens of every race and color ... avefull and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens."

President Andrew Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 amid concerns (among other things) that Congress did not have the constitutional authority to enact such a bill. Such doubts were one factor that led Congress to begin to draft and debate what would become the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Additionally, Congress wanted to protect white Unionists who were under personal and legal attack in the former Confederacy. The effort was led by the Radical Republicans of both houses of Congress, including John Bingham

John Armor Bingham (January 21, 1815 – March 19, 1900) was an American politician who served as a Republican representative from Ohio and as the United States ambassador to Japan. In his time as a congressman, Bingham served as both ass ...

, Charles Sumner, and Thaddeus Stevens. It was the most influential of these men, John Bingham, who was the principal author and drafter of the Equal Protection Clause.

The Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

states were opposed to the Civil Rights Act, but in 1865 Congress, exercising its power under Article I, Section 5, Clause 1 of the Constitution, to "be the Judge of the ... Qualifications of its own Members", had excluded Southerners from Congress, declaring that their states, having rebelled against the Union, could therefore not elect members to Congress. It was this fact—the fact that the Fourteenth Amendment was enacted by a " rump" Congress—that permitted the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment by Congress and subsequently proposed to the states. The ratification of the amendment by the former Confederate states was imposed as a condition of their acceptance back into the Union.

Ratification

With the return to originalist interpretations of the Constitution, many wonder what was intended by the framers of the reconstruction amendments at the time of their ratification. The 13th amendment abolished slavery but to what extent it protected other rights was unclear. After the 13th amendment the South began to institute Black Codes which were restrictive laws seeking to keep black Americans in a position of inferiority. The 14th amendment was ratified by nervous Republicans in response to the rise of Black Codes. This ratification was irregular in many ways. First, there were multiple states that rejected the 14th amendment, but when their new governments were created due to reconstruction, these new governments accepted the amendment. There were also two states, Ohio and New Jersey, that accepted the amendment and then later passed resolutions rescinding that acceptance. The nullification of the two state's acceptance was considered illegitimate and both Ohio and New Jersey were included in those counted as ratifying the amendment. Many historians have argued that 14th amendment was not originally intended to grant sweeping political and social rights to the citizens but instead to solidify the constitutionality of the 1866 Civil rights Act. While it is widely agreed that this was a key reason for the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, many historians adopt a much wider view. It is a popular interpretation that the Fourteenth Amendment was always meant to ensure equal rights for all those in the United States. This argument was used by Charles Sumner when he used the 14th amendment as the basis for his arguments to expand the protections afforded to black Americans. Although the equal protection clause is one of the most cited ideas in legal theory, it received little attention during the ratification of the 14th amendment. Instead the key tenet of the Fourteenth Amendment at the time of its ratification was the Privileges or Immunities Clause. This clause sought to protect the privileges and immunities of all citizens which now included black men. The scope of this clause was substantially narrowed following theSlaughterhouse Cases

The ''Slaughter-House Cases'', 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision consolidating several cases that held that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution only prote ...

in which it was determined that a citizen's privileges and immunities were only ensured at the Federal level and that it was government overreach to impose this standard on the states. Even in this halting decision the Court still acknowledged the context in which the Amendment was passed, stating that knowing the evils and injustice the 14th amendment was meant to combat is key in our legal understanding of its implications and purpose. With the abridgment of the Privileges or Immunities clause, legal arguments aimed at protecting black American's rights became more complex and that is when the equal protection clause started to gain attention for the arguments it could enhance.

During the debate in Congress, more than one version of the clause was considered. Here is the first version: "The Congress shall have power to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper to secure ... to all persons in the several states equal protection in the rights of life, liberty, and property."Kelly, Alfred.Clio and the Court: An Illicit Love Affair

, ''The Supreme Court Review'' at p. 148 (1965) reprinted in ''The Supreme Court in and of the Stream of Power'' (Kermit Hall ed., Psychology Press 2000). Bingham said about this version: "It confers upon Congress power to see to it that the protection given by the laws of the States shall be equal in respect to life and liberty and property to all persons." The main opponent of the first version was Congressman Robert S. Hale of New York, despite Bingham's public assurances that "under no possible interpretation can it ever be made to operate in the State of New York while she occupies her present proud position." Hale ended up voting for the final version, however. When Senator

Jacob Howard

Jacob Merritt Howard (July 10, 1805 – April 2, 1871) was an American attorney and politician. He was most notable for his service as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from the state of Michigan, and his political career spanned the Ame ...

introduced that final version, he said:

It prohibits the hanging of a black man for a crime for which the white man is not to be hanged. It protects the black man in his fundamental rights as a citizen with the same shield which it throws over the white man. Ought not the time to be now passed when one measure of justice is to be meted out to a member of one caste while another and a different measure is meted out to the member of another caste, both castes being alike citizens of the United States, both bound to obey the same laws, to sustain the burdens of the same Government, and both equally responsible to justice and to God for the deeds done in the body?The

39th United States Congress

The 39th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1865 ...

proposed the Fourteenth Amendment on June 13, 1866. A difference between the initial and final versions of the clause was that the final version spoke not just of "equal protection" but of "the equal protection of the laws". John Bingham said in January 1867: "no State may deny to any person the equal protection of the laws, including all the limitations for personal protection of every article and section of the Constitution..." By July 9, 1868, three-fourths of the states (28 of 37) ratified the amendment, and that is when the Equal Protection Clause became law.

Early history following ratification

Bingham said in a speech on March 31, 1871 that the clause meant no State could deny anyone "the equal protection of the Constitution of the United States ... rany of the rights which it guarantees to all men", nor deny to anyone "any right secured to him either by the laws and treaties of the United States or of such State." At that time, the meaning of equality varied from one state to another. Four of the original thirteen states never passed any laws barring interracial marriage, and the other states were divided on the issue in the Reconstruction era. In 1872, the

Four of the original thirteen states never passed any laws barring interracial marriage, and the other states were divided on the issue in the Reconstruction era. In 1872, the Alabama Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Alabama is the highest court in the state of Alabama. The court consists of a chief justice and eight associate justices. Each justice is elected in partisan elections for staggered six-year terms. The Supreme Court is hou ...

ruled that the state's ban on mixed-race marriage violated the "cardinal principle" of the 1866 Civil Rights Act and of the Equal Protection Clause. Almost a hundred years would pass before the U.S. Supreme Court followed that Alabama case (''Burns v. State'') in the case of '' Loving v. Virginia''. In ''Burns'', the Alabama Supreme Court said:

Marriage is a civil contract, and in that character alone is dealt with by the municipal law. The same right to make a contract as is enjoyed by white citizens, means the right to make any contract which a white citizen may make. The law intended to destroy the distinctions of race and color in respect to the rights secured by it.As for public schooling, no states during this era of

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

actually required separate schools for blacks. Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877

', pp. 321–322 (HarperCollins 2002). However, some states (e.g. New York) gave local districts discretion to set up schools that were deemed separate but equal. Bickel, Alexander.

The Original Understanding and the Segregation Decision

, ''

Harvard Law Review

The ''Harvard Law Review'' is a law review published by an independent student group at Harvard Law School. According to the ''Journal Citation Reports'', the ''Harvard Law Review''s 2015 impact factor of 4.979 placed the journal first out of 143 ...

'', Vol. 69, pp. 35–37 (1955). In contrast, Iowa and Massachusetts flatly prohibited segregated schools ever since the 1850s.

Likewise, some states were more favorable to women's legal status than others; New York, for example, had been giving women full property, parental, and widow's rights since 1860, but not the right to vote. No state or territory allowed women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

when the Equal Protection Clause took effect in 1868. In contrast, at that time African American men had full voting rights in five states.

Gilded Age interpretation and the ''Plessy'' decision

In the United States, 1877 marked the end of Reconstruction and the start of theGilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

. The first truly landmark equal protection decision by the Supreme Court was '' Strauder v. West Virginia'' (1880). A black man convicted of murder by an all-white jury challenged a West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

statute

A statute is a formal written enactment of a legislative authority that governs the legal entities of a city, state, or country by way of consent. Typically, statutes command or prohibit something, or declare policy. Statutes are rules made by ...

excluding blacks from serving on juries. Exclusion of blacks from juries, the Court concluded, was a denial of equal protection to black defendants, since the jury had been "drawn from a panel from which the State has expressly excluded every man of he defendant'srace." At the same time, the Court explicitly allowed sexism

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but it primarily affects women and girls.There is a clear and broad consensus among academic scholars in multiple fields that sexism refers pri ...

and other types of discrimination, saying that states "may confine the selection to males, to freeholders, to citizens, to persons within certain ages, or to persons having educational qualifications. We do not believe the Fourteenth Amendment was ever intended to prohibit this. ... Its aim was against discrimination because of race or color."

The next important postwar case was the '' Civil Rights Cases'' (1883), in which the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1875

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, sometimes called the Enforcement Act or the Force Act, was a United States federal law enacted during the Reconstruction era in response to civil rights violations against African Americans. The bill was passed by the ...

was at issue. The Act provided that all persons should have "full and equal enjoyment of ... inns, public conveyances on land or water, theatres, and other places of public amusement." In its opinion, the Court explicated what has since become known as the " state action doctrine", according to which the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause apply only to acts done or otherwise "sanctioned in some way" by the state. Prohibiting blacks from attending plays or staying in inns was "simply a private wrong". Justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

John Marshall Harlan dissented alone, saying, "I cannot resist the conclusion that the substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the Constitution have been sacrificed by a subtle and ingenious verbal criticism." Harlan went on to argue that because (1) "public conveyances on land and water" use the public highways, and (2) innkeepers engage in what is "a quasi-public employment", and (3) "places of public amusement" are licensed under the laws of the states, excluding blacks from using these services ''was'' an act sanctioned by the state.

A few years later, Justice Stanley Matthews wrote the Court's opinion in ''Yick Wo v. Hopkins

''Yick Wo v. Hopkins'', 118 U.S. 356 (1886), was the first case where the United States Supreme Court ruled that a law that is race-neutral on its face, but is administered in a prejudicial manner, is an infringement of the Equal Protection Claus ...

'' (1886). In it the word "person" from the 14th Amendment's section has been given the broadest possible meaning by the U.S. Supreme Court:

These provisions are universal in their application to all persons within the territorial jurisdiction, without regard to any differences of race, of color, or of nationality, and the equal protection of the laws is a pledge of the protection of equal laws.Thus, the Clause would not be limited to discrimination against African Americans, but would extend to other races, colors, and nationalities such as (in this case) legal aliens in the United States who are Chinese citizens. In its most contentious Gilded Age interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause, '' Plessy v. Ferguson'' (1896), the Supreme Court upheld a

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

Jim Crow law

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the S ...

that required the segregation of blacks and whites on railroads and mandated separate railway cars for members of the two races. The Court, speaking through Justice Henry B. Brown

Henry Billings Brown (March 2, 1836 – September 4, 1913) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1891 to 1906.

Although a respected lawyer and U.S. District Judge before ascending to the high court, Brown ...

, ruled that the Equal Protection Clause had been intended to defend equality in civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

, not equality in social arrangements. All that was therefore required of the law was reasonableness, and Louisiana's railway law amply met that requirement, being based on "the established usages, customs and traditions of the people." Justice Harlan again dissented. "Every one knows," he wrote,

Such "arbitrary separation" by race, Harlan concluded, was "a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law

Equality before the law, also known as equality under the law, equality in the eyes of the law, legal equality, or legal egalitarianism, is the principle that all people must be equally protected by the law. The principle requires a systematic r ...

established by the Constitution." Harlan's philosophy of constitutional colorblindness would eventually become more widely accepted, especially after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Rights of Corporations

In the decades after ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, the vast majority of Supreme Court cases interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment dealt with the rights of corporations, not with the rights of African Americans. In the period 1868-1912 (from ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment to the first known published count by a scholar), the Supreme Court interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment in 312 cases dealing with the rights of corporations but in only 28 cases dealing with the rights of African Americans. Thus, the Fourteenth Amendment was used primarily by corporations to attack laws that regulated corporations, not to protect the formerly enslaved people from racial discrimination. Granting rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to business corporations was introduced into Supreme Court jurisprudence through a series of sleights of hands.Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He is remembered today as the leader of the ...

, a skillful lawyer and former powerful politicians who had served as a member of the United States Congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which had drafted the Fourteenth Amendment, was the lawyer who argued an important case known as ''San Mateo County v. Southern Pacific Railroad'' before the Supreme Court in 1882. In this case, the issue was whether corporations are “persons” within the meaning of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Conkling argued that corporations were included in the meaning of the term person and thus entitled to such rights. He told the Court that he, as a member of the Committee that drafted this amendment to the Constitutional, knew that this is what the Committee had intended. Legal historians in the 20th Century examined the history of the drafting of the Fourteenth Amendment and found that Conkling had fabricated the notion that the Committee had intended the term “person” of the Fourteenth Amendment to encompass corporations. This ''San Mateo'' case was settled by the parties without the Supreme Court issuing an opinion however the Court's misunderstanding of the intention of the Amendment's drafters that had been created by Conkling’s likely deliberate deception was never corrected at the time.

A second fraud occurred a few years later in the case of ''Santa Clara v. Southern Pacific Railroad'', which left a written legacy of corporate rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. J. C. Bancroft Davis

John Chandler Bancroft Davis (December 29, 1822 – December 27, 1907), commonly known as (J. C.) Bancroft Davis, was an attorney, diplomat, judge of the Court of Claims and Reporter of Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Edu ...

, an attorney and the Reporter of Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States

The reporter of decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States is the official charged with editing and publishing the opinions of the Supreme Court of the United States, both when announced and when they are published in permanent bound volu ...

, drafted the “syllabus” (summary) of Supreme Court decisions and the “headnotes” that summarized key points of law held by the Court. These were published before each case as part of the official court publication communicating the law of the land as held by the Supreme Court. A headnote that Davis as court reporter published immediately preceding the court opinion in Santa Clara case stated:

Davis added before the opinion of the Court:

In fact, the Supreme Court decided the case on narrower grounds and had specifically avoided this Constitutional issue.

The Supreme Court holding

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field seized on this deceptive and incorrect published summary by the court reporter Davis in ''Santa Clara v. Southern Pacific Railroad'' and cited that case as precedent in the 1889 case ''Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway Company v. Beckwith'' in support of the proposition that corporations are entitled to equal protection of the law within the meaning of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Writing the opinion for the Court in ''Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway Company v. Beckwith'', Justice Field reasoned that a corporation is an association of its human shareholders and thus has rights under the Fourteenth Amendment just as the members of the association. In this Supreme Court case ''Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway Company v. Beckwith'', Justice Field, writing for the Court, thus took this point as established Constitutional law. In the decades that followed, the Supreme Court often continued to cite and to rely on ''Santa Clara v. Southern Pacific Railroad'' as established precedent that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed equal protection of the law and due process rights for corporations, even though in the Santa Clara case the Supreme Court held or stated no such thing. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Clause was used to strike down numerous statutes applying to corporations. Since theNew Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

, however, such invalidations have been rare.

Between ''Plessy'' and ''Brown''

In ''Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada

''Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada'', 305 U.S. 337 (1938), was a United States Supreme Court decision holding that states which provided a school to white students had to provide in-state education to blacks as well. States could satisfy this ...

'' (1938), Lloyd Gaines

Lloyd Lionel Gaines (born 1911 – disappeared March 19, 1939) was the plaintiff in '' Gaines v. Canada'' (1938), one of the most important early court cases in the 20th-century U.S. civil rights movement. After being denied admission to the ...

was a black student at Lincoln University of Missouri, one of the historically black colleges in Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

. He applied for admission to the law school at the all-white University of Missouri

The University of Missouri (Mizzou, MU, or Missouri) is a public land-grant research university in Columbia, Missouri. It is Missouri's largest university and the flagship of the four-campus University of Missouri System. MU was founded in ...

, since Lincoln did not have a law school, but was denied admission due solely to his race. The Supreme Court, applying the separate-but-equal principle of ''Plessy'', held that a State offering a legal education to whites but not to blacks violated the Equal Protection Clause.

In '' Shelley v. Kraemer'' (1948), the Court showed increased willingness to find racial discrimination illegal. The ''Shelley'' case concerned a privately made contract that prohibited "people of the Negro or Mongolian race" from living on a particular piece of land. Seeming to go against the spirit, if not the exact letter, of ''The Civil Rights Cases'', the Court found that, although a discriminatory private contract could not violate the Equal Protection Clause, the courts' ''enforcement'' of such a contract could; after all, the Supreme Court reasoned, courts were part of the state.

The companion cases '' Sweatt v. Painter'' and ''McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents __NOTOC__

''McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents'', 339 U.S. 637 (1950), was a United States Supreme Court case that prohibited racial segregation in state supported graduate or professional education.. The unanimous decision was delivered on the s ...

'', both decided in 1950, paved the way for a series of school integration cases. In ''McLaurin'', the University of Oklahoma had admitted McLaurin, an African-American, but had restricted his activities there: he had to sit apart from the rest of the students in the classrooms and library, and could eat in the cafeteria only at a designated table. A unanimous Court, through Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson

Frederick "Fred" Moore Vinson (January 22, 1890 – September 8, 1953) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 13th chief justice of the United States from 1946 until his death in 1953. Vinson was one of the few Americans to ...

, said that Oklahoma had deprived McLaurin of the equal protection of the laws:

The present situation, Vinson said, was the former. In ''Sweatt'', the Court considered the constitutionality of Texas's state system of law school

A law school (also known as a law centre or college of law) is an institution specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for becoming a lawyer within a given jurisdiction.

Law degrees Argentina

In Argentina, ...

s, which educated blacks and whites at separate institutions. The Court (again through Chief Justice Vinson, and again with no dissenters) invalidated the school system—not because it separated students, but rather because the separate facilities were not ''equal''. They lacked "substantial equality in the educational opportunities" offered to their students.

All of these cases, as well as the upcoming ''Brown'' case, were litigated by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.& ...

. It was Charles Hamilton Houston, a Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

graduate and law professor at Howard University, who in the 1930s first began to challenge racial discrimination in the federal courts. Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

, a former student of Houston's and the future Solicitor General and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, joined him. Both men were extraordinarily skilled appellate

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

advocates, but part of their shrewdness lay in their careful choice of ''which'' cases to litigate, selecting the best legal proving grounds for their cause.

''Brown'' and its consequences

In 1954 the contextualization of the equal protection clause would change forever. The Supreme Court itself recognized the gravity of the Brown v Board decision acknowledging that a split decision would be a threat to the role of the Supreme Court and even to the country. WhenEarl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presided over a major shift in American constitutio ...

became Chief Justice in 1953, ''Brown'' had already come before the Court. While Vinson was still Chief Justice, there had been a preliminary vote on the case at a conference of all nine justices. At that time, the Court had split, with a majority of the justices voting that school segregation did not violate the Equal Protection Clause. Warren, however, through persuasion and good-natured cajoling—he had been an extremely successful Republican politician before joining the Court—was able to convince all eight associate justices to join his opinion declaring school segregation unconstitutional. In that opinion, Warren wrote:

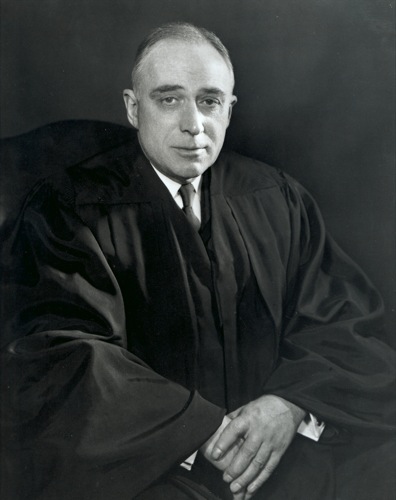

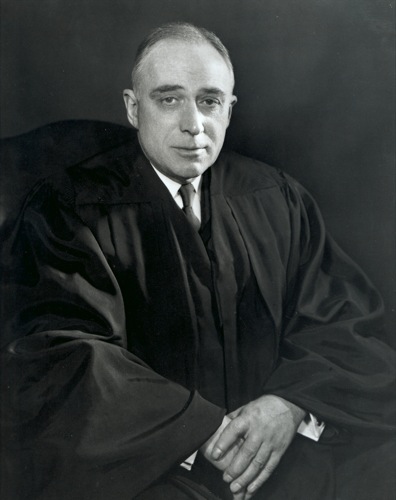

Warren discouraged other justices, such as Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1941 until his death in 1954. He had previously served as Unit ...

, from publishing any concurring opinion; Jackson's draft, which emerged much later (in 1988), included this statement: "Constitutions are easier amended than social customs, and even the North never fully conformed its racial practices to its professions". The Court set the case for re-argument on the question of how to implement the decision. In '' Brown II'', decided in 1954, it was concluded that since the problems identified in the previous opinion were local, the solutions needed to be so as well. Thus the court devolved authority to local school boards and to the trial courts

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, ...

that had originally heard the cases. (''Brown'' was actually a consolidation of four different cases from four different states.) The trial courts and localities were told to desegregate with "all deliberate speed".

Partly because of that enigmatic phrase, but mostly because of self-declared " massive resistance" in the South to the desegregation decision, integration did not begin in any significant way until the mid-1960s and then only to a small degree. In fact, much of the integration in the 1960s happened in response not to ''Brown'' but to the

Partly because of that enigmatic phrase, but mostly because of self-declared " massive resistance" in the South to the desegregation decision, integration did not begin in any significant way until the mid-1960s and then only to a small degree. In fact, much of the integration in the 1960s happened in response not to ''Brown'' but to the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requi ...

. The Supreme Court intervened a handful of times in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but its next major desegregation decision was not until ''Green v. School Board of New Kent County

''Green v. County School Board of New Kent County'', 391 U.S. 430 (1968), was an important United States Supreme Court case involving school desegregation. Specifically, the Court dealt with the freedom of choice plans created to avoid compliance ...

'' (1968), in which Justice William J. Brennan, writing for a unanimous Court, rejected a "freedom-of-choice" school plan as inadequate. This was a significant decision; freedom-of-choice plans had been very common responses to ''Brown''. Under these plans, parents could choose to send their children to either a formerly white or a formerly black school. Whites almost never opted to attend black-identified schools, however, and blacks rarely attended white-identified schools.

In response to ''Green'', many Southern districts replaced freedom-of-choice with geographically based schooling plans; because residential segregation was widespread, little integration was accomplished. In 1971, the Court in ''Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

''Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education'', 402 U.S. 1 (1971), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case dealing with the busing of students to promote integration in public schools. The Court held that busing was an appropriate ...

'' approved busing

Race-integration busing in the United States (also known simply as busing, Integrated busing or by its critics as forced busing) was the practice of assigning and transporting students to schools within or outside their local school districts in ...

as a remedy to segregation; three years later, though, in the case of ''Milliken v. Bradley

''Milliken v. Bradley'', 418 U.S. 717 (1974), was a significant United States Supreme Court case dealing with the planned desegregation busing of public school students across district lines among 53 school districts in metropolitan Detroit. It co ...

'' (1974), it set aside a lower court order that had required the busing of students ''between'' districts

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions ...

, instead of merely ''within'' a district. ''Milliken'' basically ended the Supreme Court's major involvement in school desegregation; however, up through the 1990s many federal trial courts remained involved in school desegregation cases, many of which had begun in the 1950s and 1960s.

The curtailment of busing in ''Milliken v. Bradley'' is one of several reasons that have been cited to explain why equalized educational opportunity in the United States has fallen short of completion. In the view of various liberal scholars, the election of Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

in 1968 meant that the executive branch was no longer behind the Court's constitutional commitments. Also, the Court itself decided in '' San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez'' (1973) that the Equal Protection Clause allows—but does not require—a state to provide equal educational funding to all students within the state. Moreover, the Court's decision in '' Pierce v. Society of Sisters'' (1925) allowed families to opt out of public schools, despite "inequality in economic resources that made the option of private schools available to some and not to others", as Martha Minow has put it.

American public school systems, especially in large metropolitan areas, to a large extent are still ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

'' segregated. Whether due to ''Brown'', or due to Congressional action, or due to societal change, the percentage of black students attending majority-black school districts decreased somewhat until the early 1980s, at which point that percentage began to increase. By the late 1990s, the percentage of black students in mostly minority school districts had returned to about what it was in the late 1960s. In ''Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1

''Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1'', 551 U.S. 701 (2007), also known as the ''PICS case'', is a United States Supreme Court case which found it unconstitutional for a school district to use race as a factor ...

'' (2007), the Court held that, if a school system became racially imbalanced due to social factors other than governmental racism, then the state is not as free to integrate schools as if the state had been at fault for the racial imbalance. This is especially evident in the charter school system where parents of students can pick which schools their children attend based on the amenities provided by that school and the needs of the child. It seems that race is a factor in the choice of charter school.

Application to federal government

By its terms, the clause restrains only state governments. However, the Fifth Amendment'sdue process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual per ...

guarantee, beginning with '' Bolling v. Sharpe'' (1954), has been interpreted as imposing some of the same restrictions on the federal government: "Though the Fifth Amendment does not contain an equal protection clause, as does the Fourteenth Amendment which applies only to the States, the concepts of equal protection and due process are not mutually exclusive." In ''Lawrence v. Texas

''Lawrence v. Texas'', 539 U.S. 558 (2003), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that most sanctions of criminal punishment for consensual, adult non- procreative sexual activity (commonly referred to as sod ...

'' (2003) the Supreme Court added: "Equality of treatment and the due process right to demand respect for conduct protected by the substantive guarantee of liberty are linked in important respects, and a decision on the latter point advances both interests"

Some scholars have argued that the Court's decision in ''Bolling'' should have been reached on other grounds. For example, Michael W. McConnell has written that Congress never "required that the schools of the District of Columbia be segregated." According to that rationale, the segregation of schools in Washington D.C. was unauthorized and therefore illegal.

Tiered scrutiny

Despite the undoubted importance of ''Brown'', much of modern equal protection jurisprudence originated in other cases, though not everyone agrees about ''which'' other cases. Many scholars assert that the opinion of JusticeHarlan Stone

Harlan Fiske Stone (October 11, 1872 – April 22, 1946) was an American attorney and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1925 to 1941 and then as the 12th chief justice of the United States from 1941 un ...

in ''United States v. Carolene Products Co.

''United States v. Carolene Products Company'', 304 U.S. 144 (1938), was a case of the United States Supreme Court that upheld the federal government's power to prohibit filled milk from being shipped in interstate commerce. In his majority opini ...

'' (1938) contained a footnote that was a critical turning point for equal protection jurisprudence,Goldstein, Leslie.Between the Tiers: The New(est) Equal Protection and Bush v. Gore

", ''University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law'', Vol. 4, p. 372 (2002) . but that assertion is disputed. Whatever its precise origins, the basic idea of the modern approach is that more judicial scrutiny is triggered by purported discrimination that involves " fundamental rights" (such as the right to procreation), and similarly more judicial scrutiny is also triggered if the purported victim of discrimination has been targeted because he or she belongs to a "

suspect classification

In United States constitutional law, a suspect classification is a class or group of persons meeting a series of criteria suggesting they are likely the subject of discrimination. These classes receive closer scrutiny by courts when an Equal Prot ...

" (such as a single racial group). This modern doctrine was pioneered in ''Skinner v. Oklahoma

''Skinner v. State of Oklahoma, ex rel. Williamson'', 316 U.S. 535 (1942), is a unanimous United States Supreme Court ruling. that held that laws permitting the compulsory sterilization of criminals are unconstitutional as it violates a person's ri ...

'' (1942), which involved depriving certain criminals of the fundamental right to procreate:

When the law lays an unequal hand on those who have committed intrinsically the same quality of offense and sterilizes one and not the other, it has made as invidious a discrimination as if it had selected a particular race or nationality for oppressive treatment.Until 1976, the Supreme Court usually ended up dealing with discrimination by using one of two possible levels of scrutiny: what has come to be called "

strict scrutiny

In U.S. constitutional law, when a law infringes upon a fundamental constitutional right, the court may apply the strict scrutiny standard. Strict scrutiny holds the challenged law as presumptively invalid unless the government can demonstrate th ...

" (when a suspect class or fundamental right is involved), or instead the more lenient " rational basis review". Strict scrutiny means that a challenged statute must be "narrowly tailored" to serve a "compelling" government interest, and must not have a "less restrictive" alternative. In contrast, rational basis scrutiny merely requires that a challenged statute be "reasonably related" to a "legitimate" government interest.

However, in the 1976 case of ''Craig v. Boren

''Craig v. Boren'', 429 U.S. 190 (1976), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court ruling that statutory or administrative sex classifications were subject to intermediate scrutiny under the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause..

...

'', the Court added another tier of scrutiny, called "intermediate scrutiny

Intermediate scrutiny, in U.S. constitutional law, is the second level of deciding issues using judicial review. The other levels are typically referred to as rational basis review (least rigorous) and strict scrutiny (most rigorous).

In order ...

", regarding gender discrimination. The Court may have added other tiers too, such as "enhanced rational basis" scrutiny, and "exceedingly persuasive basis" scrutiny.

All of this is known as "tiered" scrutiny, and it has had many critics, including Justice Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

who argued for a "spectrum of standards in reviewing discrimination", instead of discrete tiers. Justice John Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldes ...

argued for only one level of scrutiny, given that "there is only one Equal Protection Clause".Fleming, James.'There is Only One Equal Protection Clause': An Appreciation of Justice Stevens's Equal Protection Jurisprudence

, ''Fordham Law Review'', Vol. 74, p. 2301, 2306 (2006). The whole tiered strategy developed by the Court is meant to reconcile the principle of equal protection with the reality that most laws necessarily discriminate in some way. Choosing the standard of scrutiny can determine the outcome of a case, and the strict scrutiny standard is often described as "strict in theory and fatal in fact". In order to select the correct level of scrutiny, Justice

Antonin Scalia

Antonin Gregory Scalia (; March 11, 1936 – February 13, 2016) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2016. He was described as the intellectu ...

urged the Court to identify rights as "fundamental" or identify classes as "suspect" by analyzing what was understood when the Equal Protection Clause was adopted, instead of based upon more subjective factors.

Discriminatory intent and disparate impact

Because inequalities can be caused either intentionally or unintentionally, the Supreme Court has decided that the Equal Protection Clause itself does not forbid governmental policies that unintentionally lead to racial disparities, though Congress may have some power under other clauses of the Constitution to address unintentional disparate impacts. This subject was addressed in the seminal case of ''Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.

''Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp'', 429 U.S. 252 (1977), was a case heard by the Supreme Court of the United States dealing with a zoning ordinance that in a practical way barred families of various socio-eco ...

'' (1977). In that case, the plaintiff, a housing developer, sued a city in the suburbs of Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

that had refused to re-zone a plot of land on which the plaintiff intended to build low-income, racially integrated housing. On the face, there was no clear evidence of racially discriminatory intent on the part of Arlington Heights's planning commission. The result was racially disparate, however, since the refusal supposedly prevented mostly African-Americans and Hispanics from moving in. Justice Lewis Powell, writing for the Court, stated, "Proof of racially discriminatory intent or purpose is required to show a violation of the Equal Protection Clause." Disparate impact merely has an evidentiary value; absent a "stark" pattern, "impact is not determinative."

The result in ''Arlington Heights'' was similar to that in ''Washington v. Davis

''Washington v. Davis'', 426 U.S. 229 (1976), was a United States Supreme Court case that established that laws that have a racially discriminatory effect but were not adopted to advance a racially discriminatory purpose are valid under the U.S. Co ...

'' (1976), and has been defended on the basis that the Equal Protection Clause was not designed to guarantee equal outcomes, but rather equal opportunities; if a legislature wants to correct unintentional but racially disparate effects, it may be able to do so through further legislation. It is possible for a discriminating state to hide its true intention, and one possible solution is for disparate impact to be considered as stronger evidence of discriminatory intent. This debate, though, is currently academic, since the Supreme Court has not changed its basic approach as outlined in ''Arlington Heights''.

For an example of how this rule limits the Court's powers under the Equal Protection Clause, see ''McClesky v. Kemp

''McCleskey v. Kemp'', 481 U.S. 279 (1987), is a United States Supreme Court case, in which the death penalty sentencing of Warren McCleskey for armed robbery and murder was upheld. The Court said the "racially disproportionate impact" in the Geo ...

'' (1987). In that case a black man was convicted of murdering a white police officer and sentenced to death in the state of Georgia. A study found that killers of whites were more likely to be sentenced to death than were killers of blacks. The Court found that the defense had failed to prove that such data demonstrated the requisite discriminatory intent by the Georgia legislature and executive branch.

The “ Stop and Frisk” policy in New York allows officers to stop anyone who they feel looks suspicious. Data from police stops shows that even when controlling for variability, people who are black and those of Hispanic descent were stopped more frequently than white people, with these statistics dating back to the late 1990s. A term that has been created to describe the disproportionate number of police stops of black people is “Driving While Black.” This term is used to describe the stopping of innocent black people who are not committing any crime.

In addition to concerns that a discriminating statute can hide its true intention, there have also been concerns that facially neutral evaluative and statistical devices that are permitted by decision-makers can be subject to racial bias and unfair appraisals of ability.' As the equal protection doctrine heavily relies on the ability of neutral evaluative tools to engage in neutral selection procedures, racial biases indirectly permitted under the doctrine can have grave ramifications and result in 'uneven conditions.' ' These issues can be especially prominent in areas of public benefits, employment, and college admissions, etc.'

Voting rights

The Supreme Court ruled in ''

The Supreme Court ruled in ''Nixon v. Herndon

''Nixon v. Herndon'', 273 U.S. 536 (1927), was a United States Supreme Court decision which struck down a 1923 Texas law forbidding blacks from voting in the Texas Democratic Party primary. Due to the limited amount of Republican Party activity in ...

'' (1927) that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited denial of the vote based on race. The first modern application of the Equal Protection Clause to voting law came in '' Baker v. Carr'' (1962), where the Court ruled that the districts that sent representatives to the Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

state legislature

A state legislature is a legislative branch or body of a political subdivision in a federal system.

Two federations literally use the term "state legislature":

* The legislative branches of each of the fifty state governments of the United Sta ...

were so malapportioned (with some legislators representing ten times the number of residents as others) that they violated the Equal Protection Clause.

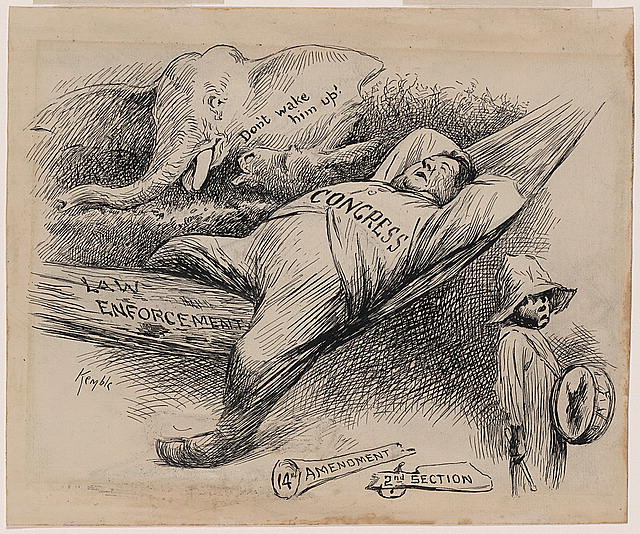

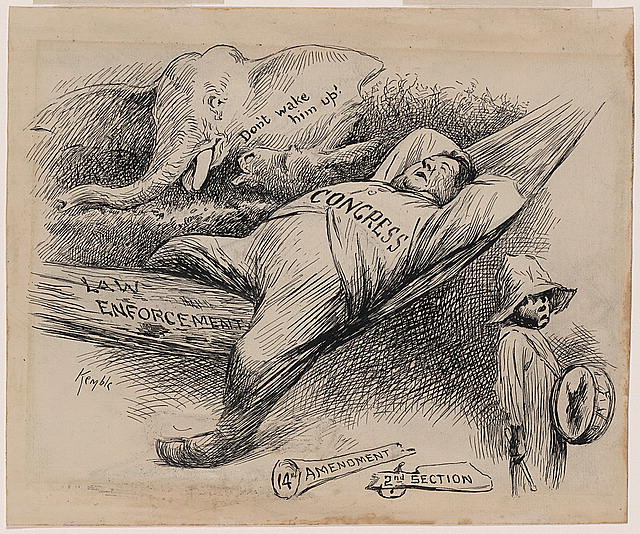

It may seem counterintuitive that the Equal Protection Clause should provide for equal voting rights; after all, it would seem to make the Fifteenth Amendment and the Nineteenth Amendment redundant. Indeed, it was on this argument, as well as on the legislative history of the Fourteenth Amendment, that Justice John M. Harlan (the grandson of the earlier Justice Harlan) relied on in his dissent from ''Reynolds''. Harlan quoted the congressional debates of 1866 to show that the framers did not intend for the Equal Protection Clause to extend to voting rights, and in reference to the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, he said:

Harlan also relied on the fact that Section Two of the Fourteenth Amendment "expressly recognizes the States' power to deny 'or in any way' abridge the right of their inhabitants to vote for 'the members of the tateLegislature.'" Section Two of the Fourteenth Amendment provides a specific federal response to such actions by a state: reduction of a state's representation in Congress. However, the Supreme Court has instead responded that voting is a "fundamental right" on the same plane as marriage ('' Loving v. Virginia''); for any discrimination in fundamental rights to be constitutional, the Court requires the legislation to pass strict scrutiny. Under this theory, equal protection jurisprudence has been applied to voting rights.

A recent use of equal protection doctrine came in '' Bush v. Gore'' (2000). At issue was the controversial recount in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

in the aftermath of the 2000 presidential election. There, the Supreme Court held that the different standards of counting ballots across Florida violated the equal protection clause. The Supreme Court used four of its rulings from 1960s voting rights cases (one of which was Reynolds v. Sims) to support its ruling in Bush v. Gore. It was not this holding that proved especially controversial among commentators, and indeed, the proposition gained seven out of nine votes; Justices Souter Souter (, ) is a Scottish surname derived from the Scots language term for a shoemaker, and may refer to:

* A nickname for any native inhabitant of the Royal Burgh of Selkirk, in the Scottish Borders

* Alexander Souter (1873–1949), Scottish bib ...

and Breyer joined the majority of five—but only for the finding that there was an Equal Protection violation. Much more controversial was the remedy that the Court chose, namely, the cessation of a statewide recount.

Sex, disability, and sexual orientation

Originally, the Fourteenth Amendment did not forbid sex discrimination to the same extent as other forms of discrimination. On the one hand, Section Two of the amendment specifically discouraged states from interfering with the voting rights of "males", which made the amendment anathema to many women when it was proposed in 1866. On the other hand, as feminists like Victoria Woodhull pointed out, the word "person" in the Equal Protection Clause was apparently chosen deliberately, instead of a masculine term that could have easily been used instead. In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court decided ''Reed v. Reed

''Reed v. Reed'', 404 U.S. 71 (1971), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States holding that the administrators of estates cannot be named in a way that discriminates between sexes. In ''Reed v. Reed'' the Supreme Court rul ...

'', extending the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to protect women from sex discrimination, in situations where there is no rational basis for the discrimination. That level of scrutiny was boosted to an intermediate level in ''Craig v. Boren

''Craig v. Boren'', 429 U.S. 190 (1976), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court ruling that statutory or administrative sex classifications were subject to intermediate scrutiny under the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause..

...

'' (1976).

The Supreme Court has been disinclined to extend full "suspect classification

In United States constitutional law, a suspect classification is a class or group of persons meeting a series of criteria suggesting they are likely the subject of discrimination. These classes receive closer scrutiny by courts when an Equal Prot ...

" status (thus making a law that categorizes on that basis subject to greater judicial scrutiny) for groups other than racial minorities and religious groups. In ''City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc.

''City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc.'', 473 U.S. 432 (1985), was a U.S. Supreme Court case involving discrimination against the intellectually disabled.

In 1980, Cleburne Living Center, Inc. (CLC) submitted a permit application seek ...

'' (1985), the Court refused to make the developmentally disabled

Developmental disability is a diverse group of chronic conditions, comprising mental or physical impairments that arise before adulthood. Developmental disabilities cause individuals living with them many difficulties in certain areas of life, espe ...

a suspect class. Many commentators have noted, however—and Justice Thurgood Marshall so notes in his partial concurrence—that the Court did appear to examine the City of Cleburne's denial of a permit to a group home for intellectually disabled people with a significantly higher degree of scrutiny than is typically associated with the rational-basis test.

The Court's decision in '' Romer v. Evans'' (1996) struck down a Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

constitutional amendment aimed at denying homosexuals "minority status, quota preferences, protected status or claim of discrimination." The Court rejected as "implausible" the dissent's argument that the amendment would not deprive homosexuals of general protections provided to everyone else but rather would merely prevent "special treatment of homosexuals." Much as in ''City of Cleburne'', the ''Romer'' decision seemed to employ a markedly higher level of scrutiny than the nominally applied rational-basis test.

In ''Lawrence v. Texas

''Lawrence v. Texas'', 539 U.S. 558 (2003), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that most sanctions of criminal punishment for consensual, adult non- procreative sexual activity (commonly referred to as sod ...

'' (2003), the Court struck down a Texas statute prohibiting homosexual sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non- procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''s ...

on substantive due process grounds. In Justice Sandra Day O'Connor

Sandra Day O'Connor (born March 26, 1930) is an American retired attorney and politician who served as the first female associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1981 to 2006. She was both the first woman nominated and th ...

's opinion concurring in the judgment, however, she argued that by prohibiting only ''homosexual'' sodomy, and not ''heterosexual'' sodomy as well, Texas's statute did not meet rational-basis review under the Equal Protection Clause; her opinion prominently cited ''City of Cleburne'', and also relied in part on ''Romer''. Notably, O'Connor's opinion did not claim to apply a higher level of scrutiny than mere rational basis, and the Court has not extended suspect-class status to sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generall ...

.

While the courts have applied rational-basis scrutiny to classifications based on sexual orientation, it has been argued that discrimination based on sex should be interpreted to include discrimination based on sexual orientation, in which case intermediate scrutiny could apply to gay rights cases. Other scholars disagree, arguing that "homophobia" is distinct from sexism, in a sociological sense, and so treating it as such would be an unacceptable judicial shortcut.

In 2013, the Court struck down part of the federal Defense of Marriage Act, in '' United States v. Windsor''. No state statute was in question, and therefore the Equal Protection Clause did not apply. The Court did employ similar principles, however, in combination with federalism

Federalism is a combined or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments ( provincial, state, cantonal, territorial, or other sub-unit governments) in a single ...

principles. The Court did not purport to use any level of scrutiny more demanding than rational basis review, according to law professor Erwin Chemerinsky

Erwin Chemerinsky (born May 14, 1953) is an American legal scholar known for his studies of United States constitutional law and federal civil procedure. Since 2017, Chemerinsky has been the dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law. Previously, he a ...

. The four dissenting justices argued that the authors of the statute were rational.

In 2015, the Supreme Court held in '' Obergefell v. Hodges'' that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and required all states to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples and to recognize same-sex marriages validly performed in other jurisdictions.

Affirmative action

Affirmative action is the consideration of race, gender, or other factors, to benefit an underrepresented group or to address past injustices done to that group. Individuals who belong to the group are preferred over those who do not belong to the group, for example in educational admissions, hiring, promotions, awarding of contracts, and the like. Such action may be used as a "tie-breaker" if all other factors are inconclusive, or may be achieved through quotas, which allot a certain number of benefits to each group. DuringReconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, Congress enacted race-conscious programs primarily to assist newly freed slaves who had personally been denied many advantages earlier in their lives. Such legislation was enacted by many of the same people who framed the Equal Protection Clause, though that clause did not apply to such federal legislation, and instead only applied to state legislation. Likewise, the Equal Protection Clause does not apply to private universities and other private businesses, which are free to practice affirmative action unless prohibited by federal statute or state law.

Several important affirmative action cases to reach the Supreme Court have concerned government contractors—for instance, '' Adarand Constructors v. Peña'' (1995) and ''City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.

''City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.'', 488 U.S. 469 (1989), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court held that the minority set-aside program of Richmond, Virginia, which gave preference to minority business enterprises (MBE) in the ...

'' (1989). But the most famous cases have dealt with affirmative action as practiced by public universities: '' Regents of the University of California v. Bakke'' (1978), and two companion cases decided by the Supreme Court in 2003, '' Grutter v. Bollinger'' and ''Gratz v. Bollinger

''Gratz v. Bollinger'', 539 U.S. 244 (2003), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding the University of Michigan undergraduate affirmative action admissions policy. In a 6–3 decision announced on June 23, 2003, Chief Justice Rehnq ...

''.