End of World War II in Asia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

On August 6, 1945, a gun-type

On August 6, 1945, a gun-type

; September 2, 1945: Japanese garrison in

; September 2, 1945: Japanese garrison in

During the

During the

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

officially ended in Asia on September 2, 1945, with the surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Na ...

on the . Before that, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, and the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, causing Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

to announce the acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration on August 15, 1945, which would eventually lead to the surrender ceremony on September 2.

After the ceremony, Japanese forces continued to surrender across the Pacific, with the last major surrender occurring on October 25, 1945, with the surrender of Japanese forces in Taiwan to Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

. The Americans occupied Japan

Japan was occupied and administered by the victorious Allies of World War II from the 1945 surrender of the Empire of Japan at the end of the war until the

Treaty of San Francisco took effect in 1952. The occupation, led by the United State ...

after the end of the war until April 28, 1952, when the Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

came into effect.

Prelude

Soviet agreements to invade Japan

At theTehran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embass ...

, between November 28 and December 1, 1943, the Soviet Union agreed to invade Japan "after the defeat of Germany", but this would not be finalized until the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

between February 4 and February 11, 1945, when the Soviet Union agreed to invade Japan within 2 or 3 months. On April 5, 1945, the Soviet Union denounced the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact

The , also known as the , was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II ...

that had been signed on April 13, 1941, as now the Soviet Union had plans for war with Japan.

Surrender of Axis forces in Europe

Japan's biggest allies in Europe began to surrender in 1945, with the last Italian troops surrender in the "Rendition of Caserta" on April 29, 1945, and the Germans surrendering on May 8, 1945, leaving Japan as the last major Axis power standing.The Potsdam Conference and Declaration

On July 17, 1945, thePotsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

began. While mostly dealing with events in Europe after the Axis surrenders, the Allies also discussed the war against Japan, leading to the Potsdam Declaration being issued on July 26, 1945, calling for the unconditional surrender of Japan, and "prompt and utter destruction" if Japan failed to surrender. Yet, the ultimatum also claimed that Japan would not "be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation".

Japan's peace attempts and response to the Potsdam Declaration

= Peace attempts

= Before the Potsdam Declaration was issued, Japan had wanted to attempt peace with the Allies, with some early moves by the government apparent as early as the spring of 1944. By the time the Suzuki cabinet took office on April 7, 1945, it became clear that the government's unannounced aim was to secure peace. The repeated attempts to establish unofficial communication with the Allies included sending PrinceFumimaro Konoe

Prince was a Japanese politician and prime minister. During his tenure, he presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the breakdown in relations with the United States, which ultimately culminated in Japan's entry into World W ...

to Moscow to try to get the Soviet Union to make the Americans stop the war. However, the Soviet Union did not want the Allies to have peace with Japan until they declared war on Japan.

= Response to the Potsdam Declaration

= When the Potsdam Declaration was issued, Japan's government followed a policy of ''mokusatsu'', which can be roughly translated as "to withhold comment", most likely the closest to what the government meant. However, Japan's propaganda agencies, like Radio Tokyo and the Domei News Agency, broadcast that Japan was "ignoring" the Potsdam Declaration, another possible translation of ''mokusatsu'', making it seem like Japan outright ignored the Potsdam Declaration, leading to the United States dropping nuclear weapons on Japan a few days later.Final stages

Before the informal surrender of Japan

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

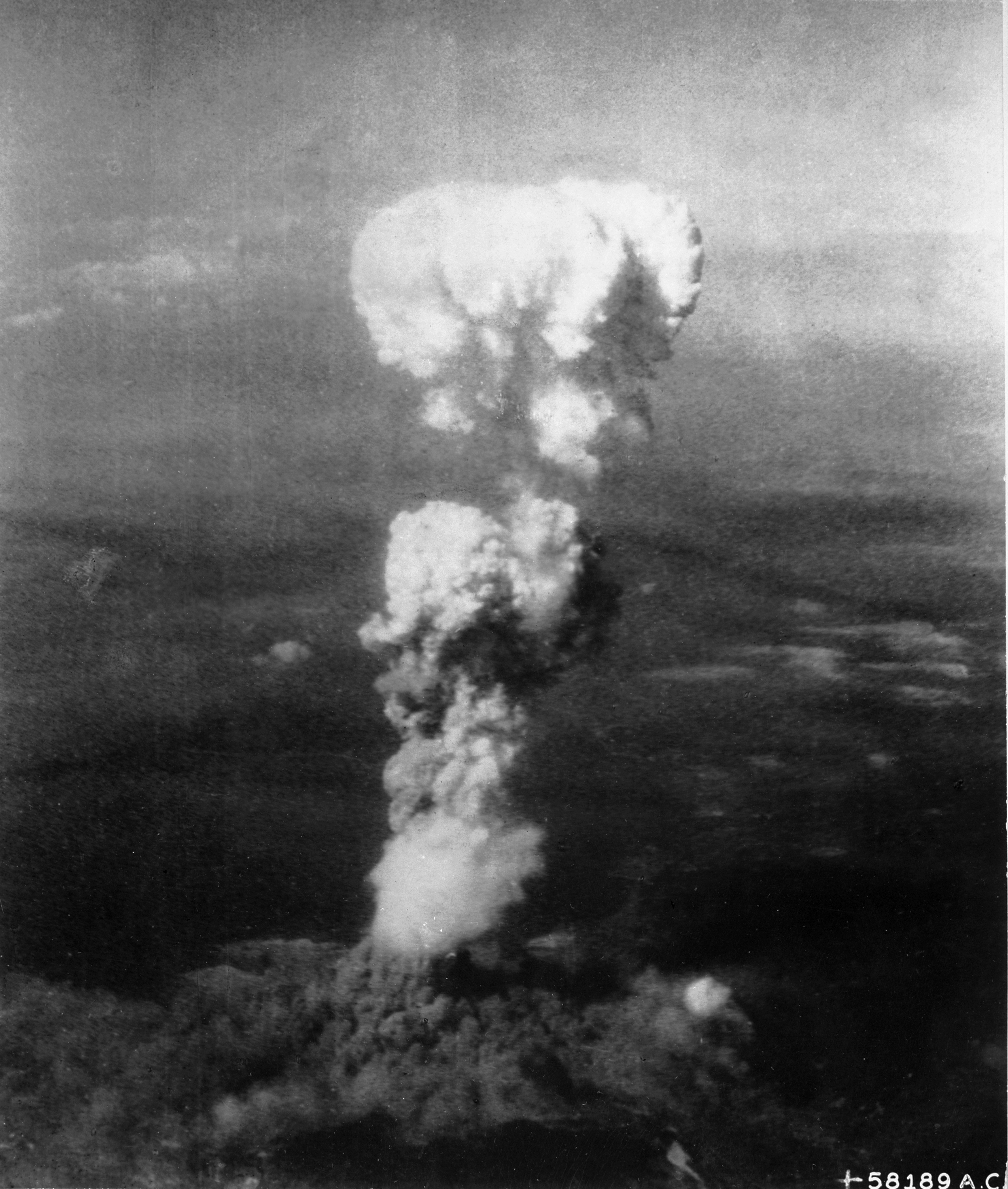

On August 6, 1945, a gun-type

On August 6, 1945, a gun-type nuclear bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

, Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

, was dropped on Hiroshima from a special B-29 Superfortress named ''Enola Gay

The ''Enola Gay'' () is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Colonel Paul Tibbets. On 6 August 1945, piloted by Tibbets and Robert A. Lewis during the final stages of World War II, it ...

'', flown by Col. Paul Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007) was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force. He is best known as the aircraft captain who flew the B-29 Superfortress known as the ''Enola Gay'' (named after his moth ...

. It was the first use of atomic weapons in combat. 70,000 were killed instantly; 30,000 more would die by the end of the year. Hiroshima was chosen as the target to demonstrate the destructiveness of the bomb.

After the bombing of Hiroshima, Harry Truman said that "We have spent two billion dollars on the greatest scientific gamble in history—and won." Japan still continued the war, though, despite some officials' attempts to make peace through the Soviets.

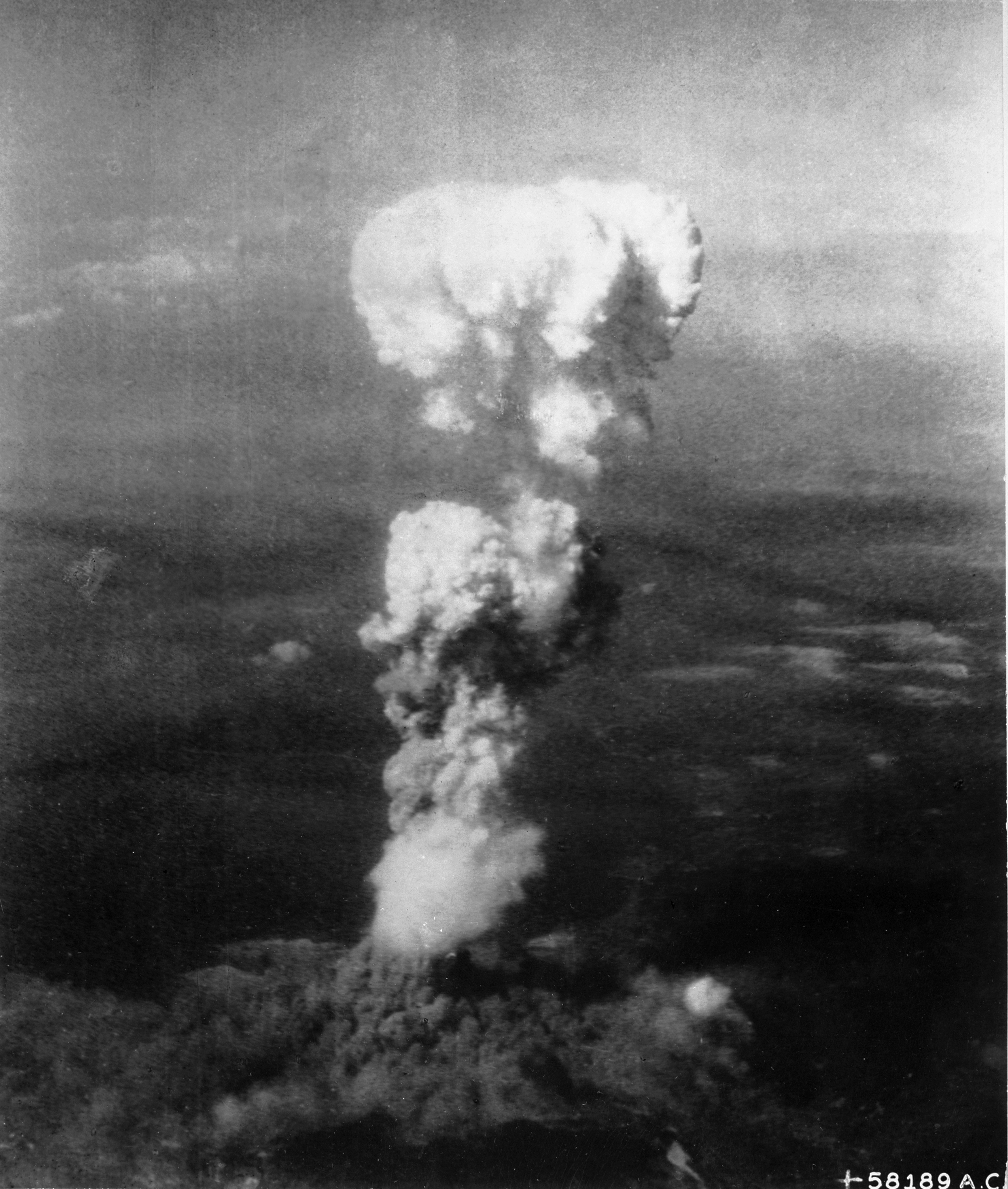

On August 9, 1945, a second, and more powerful plutonium implosion atomic bomb, Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

, was dropped on Nagasaki from a different ''Silverplate'' B-29 named ''Bockscar

''Bockscar'', sometimes called Bock's Car, is the name of the United States Army Air Forces B-29 bomber that dropped a Fat Man nuclear weapon over the Japanese city of Nagasaki during World War II in the secondand most recent nuclear attack in ...

'', flown by Major General Charles Sweeney

Charles William Sweeney (December 27, 1919 – July 16, 2004) was an officer in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II and the pilot who flew ''Bockscar'' carrying the Fat Man atomic bomb to the Japanese city of Nagasaki on Augu ...

. The original target was Kokura, but thick clouds covered the city, so the plane was flown to the secondary target, Nagasaki, instead. It killed 40,000 instantly, and another 30,000 would die by the end of the year.

The atomic bombings were one possible reason why Emperor Hirohito decided to surrender to the Allies.

Soviet war against Japan

On August 8, 1945, theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

declared war on Japan, breaking the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact

The , also known as the , was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II ...

This dashed any hopes of peace negotiated through the Soviet Union and was a big factor in the surrender of Japan The next day after, Soviet armies invaded Manchuria, attacking from all sides, except the south. On August 10, 1945, Soviet forces invaded Karafuto Prefecture

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became ter ...

. Following the declaration, Japan was at war with almost all non-neutral nations.

Korea

On August 11, 1945, with the drafting of General Order No. 1, the 38th Parallel was set as the delineation between the Soviet and US occupation zones in Korea, with Japanese forces north the parallel surrendering to the Soviets, and south of it surrendering to the Americans.The informal Japanese surrender

On August 9, after the Nagasaki atomic bombing, shortly before midnight, Hirohito entered a meeting with his cabinet, where he said that he did not believe Japan could continue to fight the war. The next day, the Japanese Foreign Ministry transmitted to the Allies that they would accept the Potsdam Declaration. In the evening of August 14, Hirohito was recorded accepting the Potsdam Declaration at the NHK broadcasting studio. It would not bebroadcast

Broadcasting is the distribution of audio or video content to a dispersed audience via any electronic mass communications medium, but typically one using the electromagnetic spectrum (radio waves), in a one-to-many model. Broadcasting began wi ...

until the next day at noon.

After the informal surrender

Douglas MacArthur

GeneralDouglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

was the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) to the Japanese government, aiming to suppress its "milit ...

, and as such had complete control over the occupation of Japan. He issued General Order No. 1 on August 17, which ordered all Japanese forces to unconditionally surrender to an Allied power in the Pacific, depending on the location. On August 30, General Douglas MacArthur arrived at Atsugi Air Base

is a joint Japan-US naval air base located in the cities of Yamato and Ayase in Kanagawa, Japan. It is the largest United States Navy (USN) air base in the Pacific Ocean and once housed the squadrons of Carrier Air Wing Five (CVW-5), whi ...

in Japan to begin the occupation of Japan

Japan was occupied and administered by the victorious Allies of World War II from the 1945 surrender of the Empire of Japan at the end of the war until the

Treaty of San Francisco took effect in 1952. The occupation, led by the United States ...

by the Allied Powers.

Last air casualty

On August 18, Japanese pilots attacked two B-32s of the 386th Bombardment Squadron and312th Bombardment Group

31 may refer to:

* 31 (number)

Years

* 31 BC

* AD 31

* 1931 CE ('31)

* 2031 CE ('31)

Music

* ''Thirty One'' (Jana Kramer album), 2015

* ''Thirty One'' (Jarryd James album), 2015

* "Thirty One", a song by Karma to Burn from the album ''Wild, ...

on a photo reconnaissance mission over Japan. Sergeant Anthony Marchione, 19, a photographer's assistant, was fatally wounded in the attack and would be the last American killed in air combat in the Second World War.

Allied operations after the informal surrender

= Troop actions

= On August 18, Soviet troops began invading the Kuril Islands, starting with amphibious landings in Shumshu. Five days later, the last Japanese troops there surrendered.Russell, Richard A., ''Project Hula: Secret Soviet-American Cooperation in the War Against Japan'', Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1997, , pp. 30-31. On August 30, after the informal surrender, British forces returned to Hong Kong. ; August 27, 1945: B-29s begin to drop supplies to prisoners in Japanese camps as part of Operation "Blacklist", which included providing Alliedprisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

with adequate supplies and care and to evacuate them from their prisons.

; August 29, 1945: A B-29 was shot down over Korea supplying P.O.W.s in the camp of Konan. Bill Streifer and Irek Sabitov argue the Soviets shot the plane down to prevent the Americans from identifying facilities supporting Japan's atomic bomb program.

; September 2, 1945: Formal Japanese surrender ceremony aboard in Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan, and spans the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. The Tokyo Bay region is both the most populou ...

; U.S. President Harry S. Truman declares Victory over Japan Day.

Aftermath

; September 2, 1945: Japanese garrison in

; September 2, 1945: Japanese garrison in Penang

Penang ( ms, Pulau Pinang, is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Malacca Strait. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the M ...

surrenders, while the British begin to retake Penang

Penang ( ms, Pulau Pinang, is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Malacca Strait. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the M ...

under Operation Jurist.

; September 4, 1945: Japanese troops on Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of T ...

surrender.

; September 5, 1945: The British land in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

.

; September 5, 1945: The Soviets complete their occupation of the Kuril Islands.

; September 6, 1945: Japanese forces in Rabaul

Rabaul () is a township in the East New Britain province of Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. It lies about 600 kilometres to the east of the island of New Guinea. Rabaul was the provincial capital and most important settlement in ...

and across Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

surrender.

; September 8, 1945: MacArthur enters Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

.

; September 8, 1945: US forces land at Incheon

Incheon (; ; or Inch'ŏn; literally "kind river"), formerly Jemulpo or Chemulp'o (제물포) until the period after 1910, officially the Incheon Metropolitan City (인천광역시, 仁川廣域市), is a city located in northwestern South Kore ...

to occupy Korea south of the 38th parallel.

; September 9, 1945: Japanese forces in China surrender.

; September 9, 1945: Japanese forces on the Korean Peninsula surrender.

; September 10, 1945: Japanese forces in Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and e ...

surrender.

; September 10, 1945: Japanese in Labuan

Labuan (), officially the Federal Territory of Labuan ( ms, Wilayah Persekutuan Labuan), is a Federal Territory of Malaysia. Its territory includes and six smaller islands, off the coast of the state of Sabah in East Malaysia. Labuan's capita ...

surrender.

; September 11, 1945: Japanese in Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the Malaysian state of Sabah to the northeast, ...

surrender.

; September 12, 1945: Japanese in Singapore formally surrender.

; September 13, 1945: Japanese in Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

formally surrender.

; September 16, 1945: Japanese in Hong Kong formally surrender.

; October 25, 1945: Japanese in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

surrender to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

.

Thailand (Siam)

After Japan's defeat in 1945, most of the international community, with the exception of Britain, did not accept Thailand's declaration of war, as it had been signed under duress. Thailand was not occupied by the Allies, but it was forced to return the territory it had regained to the French. In the postwar period Thailand had relations with the United States, which it saw as a protector from the communist revolutions in neighbouring countries.Occupation of Japan

At the end of World War II, Japan was occupied by theAllies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, led by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

with contributions also from Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

. This foreign presence marked the first time in its history that the island nation had been occupied by a foreign power. The San Francisco Peace Treaty

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

, signed on September 8, 1951, marked the end of the Allied occupation, and after it came into force on April 28, 1952, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

was once again an independent country.

International Military Tribunal for the Far East

During the

During the occupation of Japan

Japan was occupied and administered by the victorious Allies of World War II from the 1945 surrender of the Empire of Japan at the end of the war until the

Treaty of San Francisco took effect in 1952. The occupation, led by the United States ...

, leading Japanese war crime charges were reserved for those who participated in a joint conspiracy to start and wage war, termed "Class A" (crimes against peace), and were brought against those in the highest decision-making bodies; "Class B" crimes were reserved for those who committed "conventional" atrocities or crimes against humanity; "Class C" crimes were reserved for those in "the planning, ordering, authorization, or failure to prevent such transgressions at higher levels in the command structure."

Twenty-eight Japanese military and political leaders were charged with Class A crimes, and more than 5,500 others were charged with Class B and C crimes, as lower-ranking war criminals. The Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

held 13 tribunals of its own, resulting in 504 convictions and 149 executions.

Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

and all members of the imperial family such as Prince Asaka, were not prosecuted for involvement in any the three categories of crimes. Herbert Bix

Herbert P. Bix (born 1938) is an American historian. He wrote ''Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan'', an account of the Japanese Emperor and the events which shaped modern Japanese imperialism, which won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfict ...

explains that "the Truman administration and General MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

both believed the occupation reforms would be implemented smoothly if they used Hirohito to legitimise their changes." As many as 50 suspects, such as Nobusuke Kishi

was a Japanese bureaucrat and politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960.

Known for his exploitative rule of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China in the 1930s, Kishi was nicknamed the "Monster of the Sh� ...

, who later became Prime Minister were charged but released without ever being brought to trial in 1947 and 1948. Shiro Ishii received immunity in exchange for data gathered from his experiments on live prisoners. The lone dissenting judge to exonerate all indictees was Indian jurist Radhabinod Pal.

The tribunal was adjourned on November 12, 1948.

See also

*Timeline of Axis surrenders in World War II

This is a timeline showing surrenders of the various fighting groups of the Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rota ...

* Japanese holdout

Japanese holdouts ( ja, 残留日本兵, translit=Zanryū nipponhei, lit=remaining Japanese soldiers) were soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy during the Pacific Theatre of World War II who continued fighting World Wa ...

* Aftermath of World War II

The aftermath of World War II was the beginning of a new era started in late 1945 (when World War II ended) for all countries involved, defined by the decline of all colonial empires and simultaneous rise of two superpowers; the Soviet Union ( ...

References

{{World War II Pacific Ocean theatre of World War II 1945 in military history 1945 in Asia World War II operations and battles of the Southeast Asia Theatre South West Pacific theatre of World War II Japan campaign Chronology of World War II