Emily Dickinson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry.

Dickinson was born in

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born at the family's homestead in

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born at the family's homestead in

From the mid-1850s, Dickinson's mother became effectively bedridden with various chronic illnesses until her death in 1882. Writing to a friend in summer 1858, Dickinson said she would visit if she could leave "home, or mother. I do not go out at all, lest father will come and miss me, or miss some little act, which I might forget, should I run away – Mother is much as usual. I Know not what to hope of her".Habegger (2001). 342. As her mother continued to decline, Dickinson's domestic responsibilities weighed more heavily upon her and she confined herself within the Homestead. Forty years later, Lavinia said that because their mother was chronically ill, one of the daughters had to remain always with her. Dickinson took this role as her own, and "finding the life with her books and nature so congenial, continued to live it".

Withdrawing more and more from the outside world, Dickinson began in the summer of 1858 what would be her lasting legacy. Reviewing poems she had written previously, she began making clean copies of her work, assembling carefully pieced-together manuscript books.Habegger (2001), 353. The forty fascicles she created from 1858 through 1865 eventually held nearly eight hundred poems. No one was aware of the existence of these books until after her death.

In the late 1850s, the Dickinsons befriended Samuel Bowles, the owner and editor-in-chief of the ''

From the mid-1850s, Dickinson's mother became effectively bedridden with various chronic illnesses until her death in 1882. Writing to a friend in summer 1858, Dickinson said she would visit if she could leave "home, or mother. I do not go out at all, lest father will come and miss me, or miss some little act, which I might forget, should I run away – Mother is much as usual. I Know not what to hope of her".Habegger (2001). 342. As her mother continued to decline, Dickinson's domestic responsibilities weighed more heavily upon her and she confined herself within the Homestead. Forty years later, Lavinia said that because their mother was chronically ill, one of the daughters had to remain always with her. Dickinson took this role as her own, and "finding the life with her books and nature so congenial, continued to live it".

Withdrawing more and more from the outside world, Dickinson began in the summer of 1858 what would be her lasting legacy. Reviewing poems she had written previously, she began making clean copies of her work, assembling carefully pieced-together manuscript books.Habegger (2001), 353. The forty fascicles she created from 1858 through 1865 eventually held nearly eight hundred poems. No one was aware of the existence of these books until after her death.

In the late 1850s, the Dickinsons befriended Samuel Bowles, the owner and editor-in-chief of the ''

This highly nuanced and largely theatrical letter was unsigned, but she had included her name on a card and enclosed it in an envelope, along with four of her poems. He praised her work but suggested that she delay publishing until she had written longer, being unaware she had already appeared in print. She assured him that publishing was as foreign to her "as Firmament to Fin", but also proposed that "If fame belonged to me, I could not escape her". Dickinson delighted in dramatic self-characterization and mystery in her letters to Higginson. She said of herself, "I am small, like the wren, and my hair is bold, like the chestnut bur, and my eyes like the sherry in the glass that the guest leaves." She stressed her solitary nature, saying her only real companions were the hills, the sundown, and her dog, Carlo. She also mentioned that whereas her mother did not "care for Thought", her father bought her books, but begged her "not to read them – because he fears they joggle the Mind".

Dickinson valued his advice, going from calling him "Mr. Higginson" to "Dear friend" as well as signing her letters, "Your Gnome" and "Your Scholar". His interest in her work certainly provided great moral support; many years later, Dickinson told Higginson that he had saved her life in 1862. They corresponded until her death, but her difficulty in expressing her literary needs and a reluctance to enter into a cooperative exchange left Higginson nonplussed; he did not press her to publish in subsequent correspondence. Dickinson's own ambivalence on the matter militated against the likelihood of publication. Literary critic

This highly nuanced and largely theatrical letter was unsigned, but she had included her name on a card and enclosed it in an envelope, along with four of her poems. He praised her work but suggested that she delay publishing until she had written longer, being unaware she had already appeared in print. She assured him that publishing was as foreign to her "as Firmament to Fin", but also proposed that "If fame belonged to me, I could not escape her". Dickinson delighted in dramatic self-characterization and mystery in her letters to Higginson. She said of herself, "I am small, like the wren, and my hair is bold, like the chestnut bur, and my eyes like the sherry in the glass that the guest leaves." She stressed her solitary nature, saying her only real companions were the hills, the sundown, and her dog, Carlo. She also mentioned that whereas her mother did not "care for Thought", her father bought her books, but begged her "not to read them – because he fears they joggle the Mind".

Dickinson valued his advice, going from calling him "Mr. Higginson" to "Dear friend" as well as signing her letters, "Your Gnome" and "Your Scholar". His interest in her work certainly provided great moral support; many years later, Dickinson told Higginson that he had saved her life in 1862. They corresponded until her death, but her difficulty in expressing her literary needs and a reluctance to enter into a cooperative exchange left Higginson nonplussed; he did not press her to publish in subsequent correspondence. Dickinson's own ambivalence on the matter militated against the likelihood of publication. Literary critic

The 1880s were a difficult time for the remaining Dickinsons. Irreconcilably alienated from his wife, Austin fell in love in 1882 with

The 1880s were a difficult time for the remaining Dickinsons. Irreconcilably alienated from his wife, Austin fell in love in 1882 with

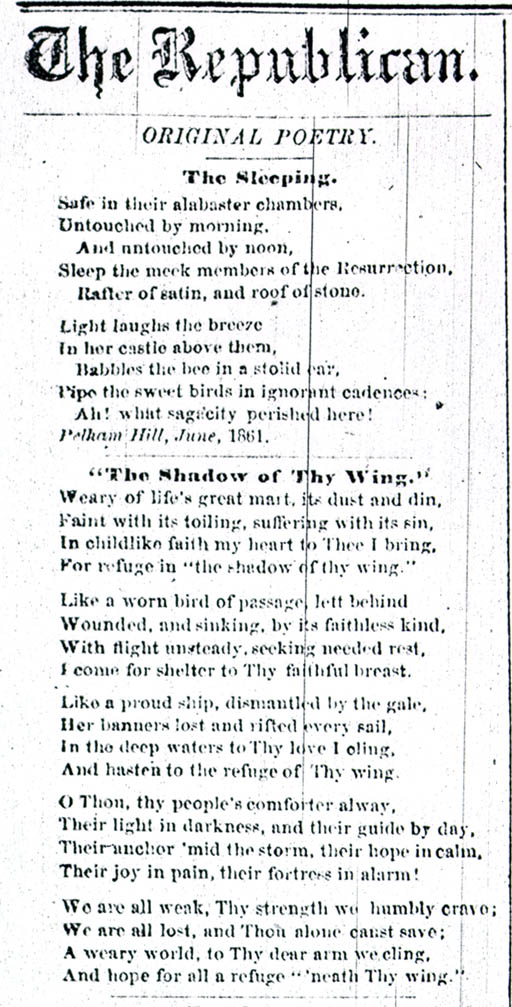

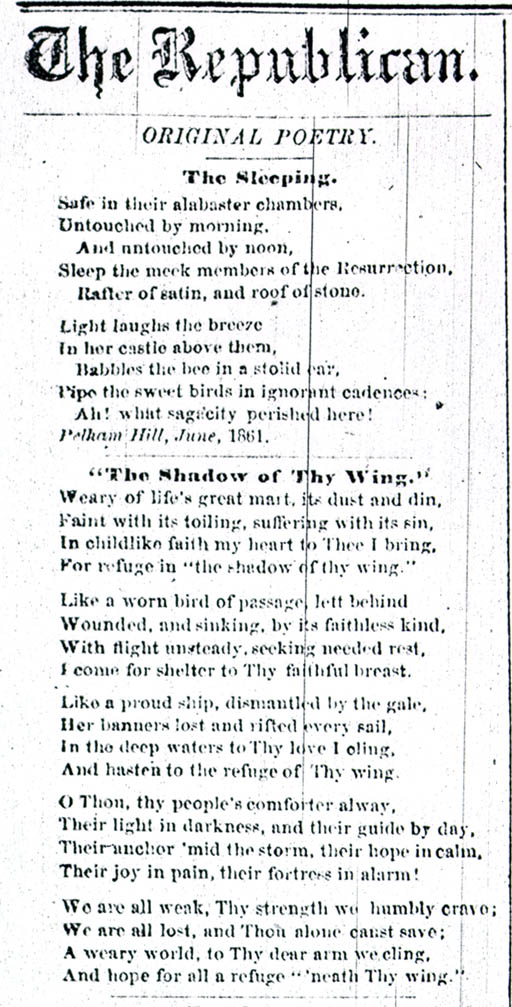

A few of Dickinson's poems appeared in Samuel Bowles' ''Springfield Republican'' between 1858 and 1868. They were published anonymously and heavily edited, with conventionalized punctuation and formal titles. The first poem, "Nobody knows this little rose", may have been published without Dickinson's permission. The ''Republican'' also published "A Narrow Fellow in the Grass" as "The Snake", "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –" as "The Sleeping", and "Blazing in the Gold and quenching in Purple" as "Sunset".Wolff (1986), 245. The poem " I taste a liquor never brewed –" is an example of the edited versions; the last two lines in the first stanza were completely rewritten.

:

In 1864, several poems were altered and published in ''Drum Beat'', to raise funds for medical care for Union soldiers in the war. Another appeared in April 1864 in the ''Brooklyn Daily Union''.

In the 1870s, Higginson showed Dickinson's poems to

A few of Dickinson's poems appeared in Samuel Bowles' ''Springfield Republican'' between 1858 and 1868. They were published anonymously and heavily edited, with conventionalized punctuation and formal titles. The first poem, "Nobody knows this little rose", may have been published without Dickinson's permission. The ''Republican'' also published "A Narrow Fellow in the Grass" as "The Snake", "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –" as "The Sleeping", and "Blazing in the Gold and quenching in Purple" as "Sunset".Wolff (1986), 245. The poem " I taste a liquor never brewed –" is an example of the edited versions; the last two lines in the first stanza were completely rewritten.

:

In 1864, several poems were altered and published in ''Drum Beat'', to raise funds for medical care for Union soldiers in the war. Another appeared in April 1864 in the ''Brooklyn Daily Union''.

In the 1870s, Higginson showed Dickinson's poems to

The first volume of Dickinson's ''Poems,'' edited jointly by Mabel Loomis Todd and T. W. Higginson, appeared in November 1890.Wolff (1986), 537. Although Todd claimed that only essential changes were made, the poems were extensively edited to match punctuation and capitalization to late 19th-century standards, with occasional rewordings to reduce Dickinson's obliquity. The first 115-poem volume was a critical and financial success, going through eleven printings in two years. ''Poems: Second Series'' followed in 1891, running to five editions by 1893; a third series appeared in 1896. One reviewer, in 1892, wrote: "The world will not rest satisfied till every scrap of her writings, letters as well as literature, has been published".

Nearly a dozen new editions of Dickinson's poetry, whether containing previously unpublished or newly edited poems, were published between 1914 and 1945. Martha Dickinson Bianchi, the daughter of Susan and Austin Dickinson, published collections of her aunt's poetry based on the manuscripts held by her family, whereas Mabel Loomis Todd's daughter,

The first volume of Dickinson's ''Poems,'' edited jointly by Mabel Loomis Todd and T. W. Higginson, appeared in November 1890.Wolff (1986), 537. Although Todd claimed that only essential changes were made, the poems were extensively edited to match punctuation and capitalization to late 19th-century standards, with occasional rewordings to reduce Dickinson's obliquity. The first 115-poem volume was a critical and financial success, going through eleven printings in two years. ''Poems: Second Series'' followed in 1891, running to five editions by 1893; a third series appeared in 1896. One reviewer, in 1892, wrote: "The world will not rest satisfied till every scrap of her writings, letters as well as literature, has been published".

Nearly a dozen new editions of Dickinson's poetry, whether containing previously unpublished or newly edited poems, were published between 1914 and 1945. Martha Dickinson Bianchi, the daughter of Susan and Austin Dickinson, published collections of her aunt's poetry based on the manuscripts held by her family, whereas Mabel Loomis Todd's daughter,

The extensive use of

The extensive use of

The surge of posthumous publication gave Dickinson's poetry its first public exposure. Backed by Higginson and with a favorable notice from

The surge of posthumous publication gave Dickinson's poetry its first public exposure. Backed by Higginson and with a favorable notice from

File:DickinsonHomestead oct2004.jpg, The Dickinson Homestead today, now the Emily Dickinson Museum

File:Emily Dickinson stamp 8c.jpg, Emily Dickinson commemorative stamp, 1971

Emily Dickinson's life and works have been the source of inspiration to artists, particularly to

Emily Dickinson's life and works have been the source of inspiration to artists, particularly to

Internet Archive

discography of Dickinson musical settings

compiled by Georgiana Strickland

"Looking at Emily"

''Amherst Magazine''. Winter 2006. Retrieved June 23, 2009. * Farr, Judith (ed). 1996. ''Emily Dickinson: A Collection of Critical Essays''. Prentice Hall International Paperback Editions. . * Farr, Judith. 2005. ''The Gardens of Emily Dickinson''. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England: Harvard University Press. . * Ford, Thomas W. 1966. ''Heaven Beguiles the Tired: Death in the Poetry of Emily Dickinson''. University of Alabama Press. * Franklin, R. W. 1998. ''The Master Letters of Emily Dickinson''.

Precision and Indeterminacy in the Poetry of Emily Dickinson

Emerson Society Quarterly, 1974 * Hecht, Anthony. 1996. "The Riddles of Emily Dickinson" in Farr (1996) 149–162. * Juhasz, Suzanne (ed). 1983. ''Feminist Critics Read Emily Dickinson''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. . * Juhasz, Suzanne. 1996. "The Landscape of the Spirit" in Farr (1996) 130–140. * Knapp, Bettina L. 1989. ''Emily Dickinson''. New York: Continuum Publishing. * Martin, Wendy (ed). 2002. ''The Cambridge Companion to Emily Dickinson''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . * McNeil, Helen. 1986. ''Emily Dickinson''. London: Virago Press. . * Mitchell, Domhnall Mitchell and Maria Stuart. 2009. ''The International Reception of Emily Dickinson''. New York: Continuum. . * Murray, Aífe. 2010. ''Maid as Muse: How Domestic Servants Changed Emily Dickinson's Life and Language''. University Press of New England. . * Murray, Aífe. 1996. "Kitchen Table Poetics: Maid Margaret Maher and Her Poet Emily Dickinson," ''The Emily Dickinson Journal''. 5(2). pp. 285–296. * Paglia, Camille. 1990. ''Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson''. Yale University Press. . * Oberhaus, Dorothy Huff. 1996. " 'Tender pioneer': Emily Dickinson's Poems on the Life of Christ" in Farr (1996) 105–119. * Parker, Peter. 2007

"New Feet Within My Garden Go: Emily Dickinson's Herbarium"

''

Dickinson Electronic Archives

Emily Dickinson Archive

Emily Dickinson poems and texts at the Academy of American Poets

Profile and poems of Emily Dickinson, including audio files

at the Poetry Foundation.

Emily Dickinson Lexicon

Emily Dickinson International Society

Emily Dickinson Museum

The Homestead and the Evergreens, Amherst, Massachusetts

Emily Dickinson at Amherst College

Amherst College Archives and Special Collections

Emily Dickinson Collection

at Houghton Library, Harvard University

Emily Dickinson Papers

Galatea Collection, Boston Public Library

Interview with Them Tammaro and Sheila Coghill

about their book ''Visiting Emily: Poems Inspired by the Life and Work of Emily Dickinson'', ''NORTHERN LIGHTS Minnesota Author Interview'' TV Series #465 (2001) {{DEFAULTSORT:Dickinson, Emily 1830 births 1886 deaths

Amherst, Massachusetts

Amherst () is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States, in the Connecticut River valley. As of the 2020 census, the population was 39,263, making it the highest populated municipality in Hampshire County (although the county seat ...

, into a prominent family with strong ties to its community. After studying at the Amherst Academy for seven years in her youth, she briefly attended the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary before returning to her family's home in Amherst.

Evidence suggests that Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation. Considered an eccentric

Eccentricity or eccentric may refer to:

* Eccentricity (behavior), odd behavior on the part of a person, as opposed to being "normal"

Mathematics, science and technology Mathematics

* Off-center, in geometry

* Eccentricity (graph theory) of a v ...

by locals, she developed a penchant for white clothing and was known for her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, to even leave her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most friendships between her and others depended entirely upon correspondence.

While Dickinson was a prolific writer, her only publications during her lifetime were 10 of her nearly 1,800 poems, and one letter. The poems published then were usually edited significantly to fit conventional poetic rules. Her poems were unique for her era; they contain short lines, typically lack titles, and often use slant rhyme

Slant can refer to:

Bias

*Bias or other non- objectivity in journalism, politics, academia or other fields

Technical

* Slant range, in telecommunications, the line-of-sight distance between two points which are not at the same level

* Slant ...

as well as unconventional capitalization

Capitalization (American English) or capitalisation (British English) is writing a word with its first letter as a capital letter (uppercase letter) and the remaining letters in lower case, in writing systems with a case distinction. The term ...

and punctuation.McNeil (1986), 2. Many of her poems deal with themes of death and immortality, two recurring topics in letters to her friends, and also explore aesthetics, society, nature, and spirituality.

Although Dickinson's acquaintances were most likely aware of her writing, it was not until after her death in 1886—when Lavinia, Dickinson's younger sister, discovered her cache of poems—that her work became public. Her first collection of poetry was published in 1890 by personal acquaintances Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd

Mabel Loomis Todd or Mabel Loomis (November 10, 1856 – October 14, 1932) was an American editor and writer. She is remembered as the editor of posthumously published editions of Emily Dickinson and also wrote several novels and logs of her ...

, though both heavily edited the content. A complete collection of her poetry became available for the first time when scholar Thomas H. Johnson published ''The Poems of Emily Dickinson'' in 1955. In 1998, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' reported on an infrared technology study revealing that much of Dickinson's work had been deliberately censored to exclude the name "Susan". At least eleven of Dickinson's poems were dedicated to her sister-in-law Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson

Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson (December 19, 1830 – May 12, 1913) was an American writer, poet, traveler, and editor. She was the sister-in-law of poet Emily Dickinson.

Life

Susan Huntington Gilbert was born December 19, 1830, in Old De ...

, though all the dedications were obliterated, presumably by Todd. These edits work to censor the nature of Emily and Susan's relationship, which many scholars have interpreted as romantic.

Life

Family and early childhood

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born at the family's homestead in

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born at the family's homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts

Amherst () is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States, in the Connecticut River valley. As of the 2020 census, the population was 39,263, making it the highest populated municipality in Hampshire County (although the county seat ...

, on December 10, 1830, into a prominent, but not wealthy, family. Her father, Edward Dickinson

Edward Dickinson (January 1, 1803 – June 16, 1874) was an American politician from Massachusetts. He is also known as the father of the poet Emily Dickinson; their family home in Amherst, the Dickinson Homestead, is a museum dedicated to her. ...

was a lawyer in Amherst and a trustee of Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zephaniah Swift Moore, Amherst is the third oldest institution of higher educati ...

. Two hundred years earlier, her patrilineal ancestors had arrived in the New World—in the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

Great Migration—where they prospered. Emily Dickinson's paternal grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, was one of the founders of Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zephaniah Swift Moore, Amherst is the third oldest institution of higher educati ...

. In 1813, he built the Homestead, a large mansion on the town's Main Street, that became the focus of Dickinson family life for the better part of a century. Samuel Dickinson's eldest son, Edward, was treasurer of Amherst College from 1835 to 1873, served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from 14 counties each divided into single-member ...

(1838–1839; 1873) and the Massachusetts Senate

The Massachusetts Senate is the upper house of the Massachusetts General Court, the bicameral state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The Senate comprises 40 elected members from 40 single-member senatorial districts in the st ...

(1842–1843), and represented Massachusetts's 10th congressional district

Massachusetts's 10th congressional district was a small district that included parts of the South Shore of Massachusetts, and all of Cape Cod and the islands. The district had existed since 1795, but was removed for the 113th Congress in 2013 ...

in the 33rd U.S. Congress (1853–1855). On May 6, 1828, he married Emily Norcross from Monson, Massachusetts

Monson is a town in Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 8,150 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The census-designated place of Monson Center lies at t ...

. They had three children:

* William Austin (1829–1895), known as Austin, Aust or Awe

* Emily Elizabeth

* Lavinia Norcross (1833–1899), known as Lavinia or Vinnie

She was also a distant cousin to Baxter Dickinson and his family, including his grandson the organist and composer Clarence Dickinson.

By all accounts, young Dickinson was a well-behaved girl. On an extended visit to Monson when she was two, Dickinson's Aunt Lavinia described her as "perfectly well and contented—She is a very good child and but little trouble." Dickinson's aunt also noted the girl's affinity for music and her particular talent for the piano, which she called "the ''moosic''".

Dickinson attended primary school in a two-story building on Pleasant Street. Her education was "ambitiously classical for a Victorian girl". Wanting his children well-educated, her father followed their progress even while away on business. When Dickinson was seven, he wrote home, reminding his children to "keep school, and learn, so as to tell me, when I come home, how many new things you have learned". While Dickinson consistently described her father in a warm manner, her correspondence suggests that her mother was regularly cold and aloof. In a letter to a confidante, Dickinson wrote she "always ran Home to Awe ustinwhen a child, if anything befell me. She was an awful Mother, but I liked her better than none."

On September 7, 1840, Dickinson and her sister Lavinia started together at Amherst Academy, a former boys' school that had opened to female students just two years earlier.Sewall (1974), 337. At about the same time, her father purchased a house on North Pleasant Street.Habegger (2001), 129. Dickinson's brother Austin later described this large new home as the "mansion" over which he and Dickinson presided as "lord and lady" while their parents were absent. The house overlooked Amherst's burial ground, described by one local minister as treeless and "forbidding".

Teenage years

Dickinson spent seven years at the academy, taking classes in English and classical literature,Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, botany, geology, history, "mental philosophy," and arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers— addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th ...

. Daniel Taggart Fiske, the school's principal at the time, would later recall that Dickinson was "very bright" and "an excellent scholar, of exemplary deportment, faithful in all school duties". Although she had a few terms off due to illness—the longest of which was in 1845–1846, when she was enrolled for only eleven weeks—she enjoyed her strenuous studies, writing to a friend that the academy was "a very fine school".

Dickinson was troubled from a young age by the "deepening menace" of death, especially the deaths of those who were close to her. When Sophia Holland, her second cousin and a close friend, grew ill from typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

and died in April 1844, Dickinson was traumatized. Recalling the incident two years later, she wrote that "it seemed to me I should die too if I could not be permitted to watch over her or even look at her face." She became so melancholic that her parents sent her to stay with family in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

to recover.Wolff (1986), 77. With her health and spirits restored, she soon returned to Amherst Academy to continue her studies. During this period, she met people who were to become lifelong friends and correspondents, such as Abiah Root, Abby Wood, Jane Humphrey, and Susan Huntington Gilbert (who later married Dickinson's brother Austin).

In 1845, a religious revival took place in Amherst, resulting in 46 confessions of faith among Dickinson's peers.Ford (1966), 47–48. Dickinson wrote to a friend the following year: "I never enjoyed such perfect peace and happiness as the short time in which I felt I had found my Savior."Habegger (2001), 168. She went on to say it was her "greatest pleasure to commune alone with the great God & to feel that he would listen to my prayers." The experience did not last: Dickinson never made a formal declaration of faith and attended services regularly for only a few years. After her church-going ended, about 1852, she wrote a poem opening: "Some keep the Sabbath going to Church – I keep it, staying at Home".

During the last year of her stay at the academy, Dickinson became friendly with Leonard Humphrey, its popular new young principal. After finishing her final term at the Academy on August 10, 1847, Dickinson began attending Mary Lyon

Mary Mason Lyon (; February 28, 1797 – March 5, 1849) was an American pioneer in women's education. She established the Wheaton Female Seminary in Norton, Massachusetts, (now Wheaton College) in 1834. She then established Mount Holyoke Femal ...

's Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (which later became Mount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a private liberal arts women's college in South Hadley, Massachusetts. It is the oldest member of the historic Seven Sisters colleges, a group of elite historically women's colleges in the Northeastern United States. ...

) in South Hadley, about ten miles (16 km) from Amherst. She stayed at the seminary for only ten months. Although she liked the girls at Holyoke, Dickinson made no lasting friendships there. The explanations for her brief stay at Holyoke differ considerably: either she was in poor health, her father wanted to have her at home, she rebelled against the evangelical fervor present at the school, she disliked the discipline-minded teachers, or she was simply homesick. Whatever the reasons for leaving Holyoke, her brother Austin appeared on March 25, 1848, to "bring erhome at all events". Back in Amherst, Dickinson occupied her time with household activities.Pickard (1967), 19. She took up baking for the family and enjoyed attending local events and activities in the budding college town.

Early influences and writing

When she was eighteen, Dickinson's family befriended a young attorney by the name of Benjamin Franklin Newton. According to a letter written by Dickinson after Newton's death, he had been "with my Father two years, before going to Worcester – in pursuing his studies, and was much in our family". Although their relationship was probably not romantic, Newton was a formative influence and would become the second in a series of older men (after Humphrey) that Dickinson referred to, variously, as her tutor, preceptor, or master. Newton likely introduced her to the writings ofWilliam Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

, and his gift to her of Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

's first book of collected poems had a liberating effect. She wrote later that he, "whose name my Father's Law Student taught me, has touched the secret Spring".Habegger (2001), 221. Newton held her in high regard, believing in and recognizing her as a poet. When he was dying of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

, he wrote to her, saying he would like to live until she achieved the greatness he foresaw. Biographers believe that Dickinson's statement of 1862— "When a little Girl, I had a friend, who taught me Immortality – but venturing too near, himself – he never returned"—refers to Newton.

Dickinson was familiar with not only the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

but also contemporary popular literature. She was probably influenced by Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Child ( Francis; February 11, 1802October 20, 1880) was an American abolitionist, women's rights activist, Native American rights activist, novelist, journalist, and opponent of American expansionism.

Her journals, both fiction an ...

's ''Letters from New York'', another gift from Newton (after reading it, she gushed "This then is a book! And there are more of them!"Ford (1966), 18.). Her brother smuggled a copy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely trans ...

's '' Kavanagh'' into the house for her (because her father might disapprove) and a friend lent her Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Brontë (, commonly ; 21 April 1816 – 31 March 1855) was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood and whose novels became classics of English literature.

She enlisted i ...

's ''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The first ...

'' in late 1849.Habegger (2001), 226. ''Jane Eyre''s influence cannot be measured, but when Dickinson acquired her first and only dog, a Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, she named him "Carlo" after the character St. John Rivers' dog. William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

was also a potent influence in her life. Referring to his plays, she wrote to one friend, "Why clasp any hand but this?" and to another, "Why is any other book needed?"

Adulthood and seclusion

In early 1850, Dickinson wrote that "Amherst is alive with fun this winter ... Oh, a very great town this is!" Her high spirits soon turned to melancholy after another death. The Amherst Academy principal, Leonard Humphrey, died suddenly of "brain congestion" at age 25. Two years after his death, she revealed to her friend Abiah Root the extent of her sadness:... some of my friends are gone, and some of my friends are sleeping – sleeping the churchyard sleep – the hour of evening is sad – it was once my study hour – my master has gone to rest, and the open leaf of the book, and the scholar at school ''alone'', make the tears come, and I cannot brush them away; I would not if I could, for they are the only tribute I can pay the departed Humphrey.During the 1850s, Dickinson's strongest and most affectionate relationship was with her sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert. Dickinson eventually sent her over three hundred letters, more than to any other correspondent, over the course of their relationship. Susan was supportive of the poet, playing the role of "most beloved friend, influence, muse, and adviser" whose editorial suggestions Dickinson sometimes followed. In an 1882 letter to Susan, Dickinson said, "With the exception of Shakespeare, you have told me of more knowledge than any one living." The importance of Dickinson's relationship with Susan has widely been overlooked due to a point of view first promoted by Mabel Loomis Todd, who was involved for many years in a relationship with Austin Dickinson and who diminished Susan's role in Dickinson's life due to her own poor relationship with her lover's wife. However, the notion of a "cruel" Susan—as promoted by her romantic rival—has been questioned, most especially by Susan and Austin's surviving children, with whom Dickinson was close. Many scholars interpret the relationship between Emily and Susan as a romantic one. In ''

The Emily Dickinson Journal

''The Emily Dickinson Journal'' (''EDJ'') is a biannual academic journal founded by Suzanne Juhasz (University of Colorado) in 1991, and it is the official publication of the Emily Dickinson International Society. The journal provides an ongoing ex ...

'' Lena Koski wrote, "Dickinson's letters to Gilbert express strong homoerotic

Homoeroticism is sexual attraction between members of the same sex, either male–male or female–female. The concept differs from the concept of homosexuality: it refers specifically to the desire itself, which can be temporary, whereas "homo ...

feelings."Koski (1996), 26–31. She quotes from many of their letters, including one from 1852 in which Dickinson proclaims, Susie, will you indeed come home next Saturday, and be my own again, and kiss me ... I hope for you so much, and feel so eager for you, feel that I cannot wait, feel that now I must have you—that the expectation once more to see your face again, makes me feel hot and feverish, and my heart beats so fast ... my darling, so near I seem to you, that I disdain this pen, and wait for a warmer language.The relationship between Emily and Susan is portrayed in the film '' Wild Nights with Emily'' and explored in the TV series '' Dickinson''. Sue married Austin in 1856 after a four-year courtship, though their marriage was not a happy one. Edward Dickinson built a house for Austin and Sue naming it the Evergreens, a stand of which was located on the west side of the Homestead. Until 1855, Dickinson had not strayed far from Amherst. That spring, accompanied by her mother and sister, she took one of her longest and farthest trips away from home. First, they spent three weeks in

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, where her father was representing Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

in Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

. Then they went to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

for two weeks to visit family. In Philadelphia, she met Charles Wadsworth, a famous minister of the Arch Street Presbyterian Church, with whom she forged a strong friendship which lasted until his death in 1882. Despite seeing him only twice after 1855 (he moved to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

in 1862), she variously referred to him as "my Philadelphia", "my Clergyman", "my dearest earthly friend" and "my Shepherd from 'Little Girl'hood".

From the mid-1850s, Dickinson's mother became effectively bedridden with various chronic illnesses until her death in 1882. Writing to a friend in summer 1858, Dickinson said she would visit if she could leave "home, or mother. I do not go out at all, lest father will come and miss me, or miss some little act, which I might forget, should I run away – Mother is much as usual. I Know not what to hope of her".Habegger (2001). 342. As her mother continued to decline, Dickinson's domestic responsibilities weighed more heavily upon her and she confined herself within the Homestead. Forty years later, Lavinia said that because their mother was chronically ill, one of the daughters had to remain always with her. Dickinson took this role as her own, and "finding the life with her books and nature so congenial, continued to live it".

Withdrawing more and more from the outside world, Dickinson began in the summer of 1858 what would be her lasting legacy. Reviewing poems she had written previously, she began making clean copies of her work, assembling carefully pieced-together manuscript books.Habegger (2001), 353. The forty fascicles she created from 1858 through 1865 eventually held nearly eight hundred poems. No one was aware of the existence of these books until after her death.

In the late 1850s, the Dickinsons befriended Samuel Bowles, the owner and editor-in-chief of the ''

From the mid-1850s, Dickinson's mother became effectively bedridden with various chronic illnesses until her death in 1882. Writing to a friend in summer 1858, Dickinson said she would visit if she could leave "home, or mother. I do not go out at all, lest father will come and miss me, or miss some little act, which I might forget, should I run away – Mother is much as usual. I Know not what to hope of her".Habegger (2001). 342. As her mother continued to decline, Dickinson's domestic responsibilities weighed more heavily upon her and she confined herself within the Homestead. Forty years later, Lavinia said that because their mother was chronically ill, one of the daughters had to remain always with her. Dickinson took this role as her own, and "finding the life with her books and nature so congenial, continued to live it".

Withdrawing more and more from the outside world, Dickinson began in the summer of 1858 what would be her lasting legacy. Reviewing poems she had written previously, she began making clean copies of her work, assembling carefully pieced-together manuscript books.Habegger (2001), 353. The forty fascicles she created from 1858 through 1865 eventually held nearly eight hundred poems. No one was aware of the existence of these books until after her death.

In the late 1850s, the Dickinsons befriended Samuel Bowles, the owner and editor-in-chief of the ''Springfield Republican

''The Republican'' is a newspaper based in Springfield, Massachusetts covering news in the Greater Springfield area, as well as national news and pieces from Boston, Worcester and northern Connecticut. It is owned by Newhouse Newspapers, a ...

'', and his wife, Mary. They visited the Dickinsons regularly for years to come. During this time Dickinson sent him over three dozen letters and nearly fifty poems. Their friendship brought out some of her most intense writing and Bowles published a few of her poems in his journal. It was from 1858 to 1861 that Dickinson is believed to have written a trio of letters that have been called "The Master Letters". These three letters, drafted to an unknown man simply referred to as "Master", continue to be the subject of speculation and contention amongst scholars.

The first half of the 1860s, after she had largely withdrawn from social life, proved to be Dickinson's most productive writing period. Modern scholars and researchers are divided as to the cause for Dickinson's withdrawal and extreme seclusion. While she was diagnosed as having "nervous prostration" by a physician during her lifetime, some today believe she may have suffered from illnesses as various as agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is a mental and behavioral disorder, specifically an anxiety disorder characterized by symptoms of anxiety in situations where the person perceives their environment to be unsafe with no easy way to escape. These situations can i ...

and epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of non-communicable neurological disorders characterized by recurrent epileptic seizures. Epileptic seizures can vary from brief and nearly undetectable periods to long periods of vigorous shaking due to abnormal electrica ...

.

Is "my Verse ... alive?"

In April 1862, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a literary critic, radicalabolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, and ex-minister, wrote a lead piece for ''The Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'' titled, "Letter to a Young Contributor". Higginson's essay, in which he urged aspiring writers to "charge your style with life", contained practical advice for those wishing to break into print. Dickinson's decision to contact Higginson suggests that by 1862 she was contemplating publication and that it may have become increasingly difficult to write poetry without an audience. Seeking literary guidance that no one close to her could provide, Dickinson sent him a letter, which read in full:

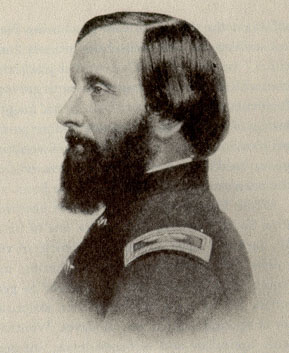

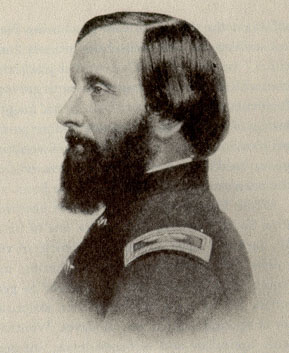

This highly nuanced and largely theatrical letter was unsigned, but she had included her name on a card and enclosed it in an envelope, along with four of her poems. He praised her work but suggested that she delay publishing until she had written longer, being unaware she had already appeared in print. She assured him that publishing was as foreign to her "as Firmament to Fin", but also proposed that "If fame belonged to me, I could not escape her". Dickinson delighted in dramatic self-characterization and mystery in her letters to Higginson. She said of herself, "I am small, like the wren, and my hair is bold, like the chestnut bur, and my eyes like the sherry in the glass that the guest leaves." She stressed her solitary nature, saying her only real companions were the hills, the sundown, and her dog, Carlo. She also mentioned that whereas her mother did not "care for Thought", her father bought her books, but begged her "not to read them – because he fears they joggle the Mind".

Dickinson valued his advice, going from calling him "Mr. Higginson" to "Dear friend" as well as signing her letters, "Your Gnome" and "Your Scholar". His interest in her work certainly provided great moral support; many years later, Dickinson told Higginson that he had saved her life in 1862. They corresponded until her death, but her difficulty in expressing her literary needs and a reluctance to enter into a cooperative exchange left Higginson nonplussed; he did not press her to publish in subsequent correspondence. Dickinson's own ambivalence on the matter militated against the likelihood of publication. Literary critic

This highly nuanced and largely theatrical letter was unsigned, but she had included her name on a card and enclosed it in an envelope, along with four of her poems. He praised her work but suggested that she delay publishing until she had written longer, being unaware she had already appeared in print. She assured him that publishing was as foreign to her "as Firmament to Fin", but also proposed that "If fame belonged to me, I could not escape her". Dickinson delighted in dramatic self-characterization and mystery in her letters to Higginson. She said of herself, "I am small, like the wren, and my hair is bold, like the chestnut bur, and my eyes like the sherry in the glass that the guest leaves." She stressed her solitary nature, saying her only real companions were the hills, the sundown, and her dog, Carlo. She also mentioned that whereas her mother did not "care for Thought", her father bought her books, but begged her "not to read them – because he fears they joggle the Mind".

Dickinson valued his advice, going from calling him "Mr. Higginson" to "Dear friend" as well as signing her letters, "Your Gnome" and "Your Scholar". His interest in her work certainly provided great moral support; many years later, Dickinson told Higginson that he had saved her life in 1862. They corresponded until her death, but her difficulty in expressing her literary needs and a reluctance to enter into a cooperative exchange left Higginson nonplussed; he did not press her to publish in subsequent correspondence. Dickinson's own ambivalence on the matter militated against the likelihood of publication. Literary critic Edmund Wilson

Edmund Wilson Jr. (May 8, 1895 – June 12, 1972) was an American writer and literary critic who explored Freudian and Marxist themes. He influenced many American authors, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose unfinished work he edited for publi ...

, in his review of Civil War literature, surmised that "with encouragement, she would certainly have published".

The woman in white

In direct opposition to the immense productivity that she displayed in the early 1860s, Dickinson wrote fewer poems in 1866. Beset with personal loss as well as loss of domestic help, Dickinson may have been too overcome to keep up her previous level of writing. Carlo died during this time after having provided sixteen years of companionship; Dickinson never owned another dog. Although the household servant of nine years, Margaret O'Brien, had married and left the Homestead that same year, it was not until 1869 that the Dickinsons brought in a permanent household servant,Margaret Maher

Margaret Maher (February 25, 1841 – May 3, 1924) was an Irish-American long-term domestic worker in the household of American poet Emily Dickinson.

Early life in Ireland

Margaret was born on February 25, 1841, in Killusty, a townland in a reg ...

, to replace their former maid-of-all-work. Emily once again was responsible for the kitchen, including cooking and cleaning up, as well as the baking at which she excelled.

Around this time, Dickinson's behavior began to change. She did not leave the Homestead unless it was absolutely necessary and as early as 1867, she began to talk to visitors from the other side of a door rather than speaking to them face to face. She acquired local notoriety; she was rarely seen, and when she was, she was usually clothed in white. Dickinson's one surviving article of clothing is a white cotton dress, possibly sewn circa 1878–1882.Habegger (2001), 516. Few of the locals who exchanged messages with Dickinson during her last fifteen years ever saw her in person. Austin and his family began to protect Dickinson's privacy, deciding that she was not to be a subject of discussion with outsiders. Despite her physical seclusion, however, Dickinson was socially active and expressive through what makes up two-thirds of her surviving notes and letters. When visitors came to either the Homestead or the Evergreens, she would often leave or send over small gifts of poems or flowers. Dickinson also had a good rapport with the children in her life. Mattie Dickinson, the second child of Austin and Sue, later said that "Aunt Emily stood for ''indulgence.''"Habegger (2001), 547. MacGregor (Mac) Jenkins, the son of family friends who later wrote a short article in 1891 called "A Child's Recollection of Emily Dickinson", thought of her as always offering support to the neighborhood children.

When Higginson urged her to come to Boston in 1868 so they could formally meet for the first time, she declined, writing: "Could it please your convenience to come so far as Amherst I should be very glad, but I do not cross my Father's ground to any House or town". It was not until he came to Amherst in 1870 that they met. Later he referred to her, in the most detailed and vivid physical account of her on record, as "a little plain woman with two smooth bands of reddish hair ... in a very plain & exquisitely clean white piqué & a blue net worsted shawl." He also felt that he never was "with any one who drained my nerve power so much. Without touching her, she drew from me. I am glad not to live near her."

Posies and poesies

Scholar Judith Farr notes that Dickinson, during her lifetime, "was known more widely as a gardener, perhaps, than as a poet". Dickinson studied botany from the age of nine and, along with her sister, tended the garden at Homestead. During her lifetime, she assembled a collection of pressed plants in a sixty-six-page leather-boundherbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant specimens and associated data used for scientific study.

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sheet of paper (calle ...

. It contained 424 pressed flower specimens that she collected, classified, and labeled using the Linnaean system. The Homestead garden was well known and admired locally in its time. It has not survived, but efforts to revive it have begun. Dickinson kept no garden notebooks or plant lists, but a clear impression can be formed from the letters and recollections of friends and family. Her niece, Martha Dickinson Bianchi, remembered "carpets of lily-of-the-valley

Lily of the valley (''Convallaria majalis'' (), sometimes written lily-of-the-valley, is a woodland flowering plant with sweetly scented, pendent, bell-shaped white flowers borne in sprays in spring. It is native throughout the cool temperate ...

and pansies

The garden pansy (''Viola'' × ''wittrockiana'') is a type of large-flowered hybrid plant cultivated as a garden flower. It is derived by hybridization from several species in the section ''Melanium'' ("the pansies") of the genus ''Viola'', p ...

, platoons of sweetpeas, hyacinths

''Hyacinthus'' is a small genus of bulbous, spring-blooming perennials. They are fragrant flowering plants in the family Asparagaceae, subfamily Scilloideae and are commonly called hyacinths (). The genus is native to the area of the eastern ...

, enough in May to give all the bees of summer dyspepsia. There were ribbons of peony

The peony or paeony is a flowering plant in the genus ''Paeonia'' , the only genus in the family Paeoniaceae . Peonies are native to Asia, Europe and Western North America. Scientists differ on the number of species that can be distinguished, ...

hedges and drifts of daffodils

''Narcissus'' is a genus of predominantly spring flowering perennial plants of the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae. Various common names including daffodil,The word "daffodil" is also applied to related genera such as ''Sternbergia'', '' Is ...

in season, marigolds to distraction—a butterfly utopia".Parker, G9. In particular, Dickinson cultivated scented exotic flowers, writing that she "could inhabit the Spice Isles merely by crossing the dining room to the conservatory, where the plants hang in baskets". Dickinson would often send her friends bunches of flowers with verses attached, but "they valued the posy more than the poetry".

Later life

On June 16, 1874, while in Boston, Edward Dickinson suffered a stroke and died. When the simple funeral was held in the Homestead's entrance hall, Dickinson stayed in her room with the door cracked open. Neither did she attend the memorial service on June 28. She wrote to Higginson that her father's "Heart was pure and terrible and I think no other like it exists." A year later, on June 15, 1875, Dickinson's mother also suffered a stroke, which produced a partial lateralparalysis

Paralysis (also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, roughly 1 in 5 ...

and impaired memory. Lamenting her mother's increasing physical as well as mental demands, Dickinson wrote that "Home is so far from Home".

Otis Phillips Lord, an elderly judge on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) is the highest court in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Although the claim is disputed by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, the SJC claims the distinction of being the oldest continuously func ...

from Salem, in 1872 or 1873 became an acquaintance of Dickinson's. After the death of Lord's wife in 1877, his friendship with Dickinson probably became a late-life romance, though as their letters were destroyed, this is surmised. Dickinson found a kindred soul in Lord, especially in terms of shared literary interests; the few letters which survived contain multiple quotations of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's work, including the plays ''Othello

''Othello'' (full title: ''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'') is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare, probably in 1603, set in the contemporary Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573) fought for the control of the Island of Cyp ...

'', ''Antony and Cleopatra

''Antony and Cleopatra'' ( First Folio title: ''The Tragedie of Anthonie, and Cleopatra'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. The play was first performed, by the King's Men, at either the Blackfriars Theatre or the Globe Theatre in aroun ...

'', ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'' and ''King Lear

''King Lear'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare.

It is based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his power and land between two of his daughters. He becomes destitute and insane a ...

''. In 1880 he gave her Cowden Clarke's ''Complete Concordance to Shakespeare'' (1877). Dickinson wrote that "While others go to Church, I go to mine, for are you not my Church, and have we not a Hymn that no one knows but us?" She referred to him as "My lovely Salem" and they wrote to each other religiously every Sunday. Dickinson looked forward to this day greatly; a surviving fragment of a letter written by her states that "Tuesday is a deeply depressed Day".

After being critically ill for several years, Judge Lord died in March 1884. Dickinson referred to him as "our latest Lost". Two years before this, on April 1, 1882, Dickinson's "Shepherd from 'Little Girl'hood", Charles Wadsworth, also had died after a long illness.

Decline and death

Although she continued to write in her last years, Dickinson stopped editing and organizing her poems. She also exacted a promise from her sister Lavinia to burn her papers. Lavinia, who never married, remained at the Homestead until her own death in 1899. The 1880s were a difficult time for the remaining Dickinsons. Irreconcilably alienated from his wife, Austin fell in love in 1882 with

The 1880s were a difficult time for the remaining Dickinsons. Irreconcilably alienated from his wife, Austin fell in love in 1882 with Mabel Loomis Todd

Mabel Loomis Todd or Mabel Loomis (November 10, 1856 – October 14, 1932) was an American editor and writer. She is remembered as the editor of posthumously published editions of Emily Dickinson and also wrote several novels and logs of her ...

, an Amherst College faculty wife who had recently moved to the area. Todd never met Dickinson but was intrigued by her, referring to her as "a lady whom the people call the ''Myth''". Austin distanced himself from his family as his affair continued and his wife became sick with grief. Dickinson's mother died on November 14, 1882. Five weeks later, Dickinson wrote, "We were never intimate ... while she was our Mother – but Mines in the same Ground meet by tunneling and when she became our Child, the Affection came." The next year, Austin and Sue's third and youngest child, Gilbert—Emily's favorite—died of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over severa ...

.

As death succeeded death, Dickinson found her world upended. In the fall of 1884, she wrote, "The Dyings have been too deep for me, and before I could raise my Heart from one, another has come." That summer she had seen "a great darkness coming" and fainted while baking in the kitchen. She remained unconscious late into the night and weeks of ill health followed. On November 30, 1885, her feebleness and other symptoms were so worrying that Austin canceled a trip to Boston. She was confined to her bed for a few months, but managed to send a final burst of letters in the spring. What is thought to be her last letter was sent to her cousins, Louise and Frances Norcross, and simply read: "Little Cousins, Called Back. Emily". On May 15, 1886, after several days of worsening symptoms, Emily Dickinson died at the age of 55. Austin wrote in his diary that "the day was awful ... she ceased to breathe that terrible breathing just before the fternoonwhistle sounded for six."Habegger (2001), 627. Dickinson's chief physician gave the cause of death as Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied ...

and its duration as two and a half years.

Lavinia and Austin asked Susan to wash Dickinson's body upon her death. Susan also wrote Dickinson's obituary for the ''Springfield Republican'', ending it with four lines from one of Dickinson's poems: "Morns like these, we parted; Noons like these, she rose; Fluttering first, then firmer, To her fair repose." Lavinia was perfectly satisfied that Sue should arrange everything, knowing it would be done lovingly. Dickinson was buried, laid in a white coffin with vanilla-scented heliotrope, a lady's slipper orchid

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant.

Along with the Asteraceae, they are one of the two largest families of floweri ...

, and a "knot of blue field violets" placed about it.Wolff (1986), 535. The funeral service, held in the Homestead's library, was simple and short; Higginson, who had met her only twice, read "No Coward Soul Is Mine", a poem by Emily Brontë

Emily Jane Brontë (, commonly ; 30 July 1818 – 19 December 1848) was an English novelist and poet who is best known for her only novel, '' Wuthering Heights'', now considered a classic of English literature. She also published a book of poe ...

that had been a favorite of Dickinson's. At Dickinson's request, her "coffin asnot driven but carried through fields of buttercups" for burial in the family plot at West Cemetery on Triangle Street.Farr (2005), 3–6.

Publication

Despite Dickinson's prolific writing, only ten poems and a letter were published during her lifetime. After her younger sister Lavinia discovered the collection of nearly 1800 poems, Dickinson's first volume was published four years after her death. Until Thomas H. Johnson published Dickinson's ''Complete Poems'' in 1955, Dickinson's poems were considerably edited and altered from their manuscript versions. Since 1890 Dickinson has remained continuously in print.Contemporary

A few of Dickinson's poems appeared in Samuel Bowles' ''Springfield Republican'' between 1858 and 1868. They were published anonymously and heavily edited, with conventionalized punctuation and formal titles. The first poem, "Nobody knows this little rose", may have been published without Dickinson's permission. The ''Republican'' also published "A Narrow Fellow in the Grass" as "The Snake", "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –" as "The Sleeping", and "Blazing in the Gold and quenching in Purple" as "Sunset".Wolff (1986), 245. The poem " I taste a liquor never brewed –" is an example of the edited versions; the last two lines in the first stanza were completely rewritten.

:

In 1864, several poems were altered and published in ''Drum Beat'', to raise funds for medical care for Union soldiers in the war. Another appeared in April 1864 in the ''Brooklyn Daily Union''.

In the 1870s, Higginson showed Dickinson's poems to

A few of Dickinson's poems appeared in Samuel Bowles' ''Springfield Republican'' between 1858 and 1868. They were published anonymously and heavily edited, with conventionalized punctuation and formal titles. The first poem, "Nobody knows this little rose", may have been published without Dickinson's permission. The ''Republican'' also published "A Narrow Fellow in the Grass" as "The Snake", "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –" as "The Sleeping", and "Blazing in the Gold and quenching in Purple" as "Sunset".Wolff (1986), 245. The poem " I taste a liquor never brewed –" is an example of the edited versions; the last two lines in the first stanza were completely rewritten.

:

In 1864, several poems were altered and published in ''Drum Beat'', to raise funds for medical care for Union soldiers in the war. Another appeared in April 1864 in the ''Brooklyn Daily Union''.

In the 1870s, Higginson showed Dickinson's poems to Helen Hunt Jackson

Helen Hunt Jackson (pen name, H.H.; born Helen Maria Fiske; October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885) was an American poet and writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Native Americans by the United States government. She de ...

, who had coincidentally been at the academy with Dickinson when they were girls.Sewall (1974), 580–583. Jackson was deeply involved in the publishing world, and managed to convince Dickinson to publish her poem " Success is counted sweetest" anonymously in a volume called '' A Masque of Poets''. The poem, however, was altered to agree with contemporary taste. It was the last poem published during Dickinson's lifetime.

Posthumous

After Dickinson's death, Lavinia Dickinson kept her promise and burned most of the poet's correspondence. Significantly though, Dickinson had left no instructions about the 40 notebooks and loose sheets gathered in a locked chest.Farr (1996), 3. Lavinia recognized the poems' worth and became obsessed with seeing them published. She turned first to her brother's wife and then to Mabel Loomis Todd, his lover, for assistance. A feud ensued, with the manuscripts divided between the Todd and Dickinson houses, preventing complete publication of Dickinson's poetry for more than half a century. The first volume of Dickinson's ''Poems,'' edited jointly by Mabel Loomis Todd and T. W. Higginson, appeared in November 1890.Wolff (1986), 537. Although Todd claimed that only essential changes were made, the poems were extensively edited to match punctuation and capitalization to late 19th-century standards, with occasional rewordings to reduce Dickinson's obliquity. The first 115-poem volume was a critical and financial success, going through eleven printings in two years. ''Poems: Second Series'' followed in 1891, running to five editions by 1893; a third series appeared in 1896. One reviewer, in 1892, wrote: "The world will not rest satisfied till every scrap of her writings, letters as well as literature, has been published".

Nearly a dozen new editions of Dickinson's poetry, whether containing previously unpublished or newly edited poems, were published between 1914 and 1945. Martha Dickinson Bianchi, the daughter of Susan and Austin Dickinson, published collections of her aunt's poetry based on the manuscripts held by her family, whereas Mabel Loomis Todd's daughter,

The first volume of Dickinson's ''Poems,'' edited jointly by Mabel Loomis Todd and T. W. Higginson, appeared in November 1890.Wolff (1986), 537. Although Todd claimed that only essential changes were made, the poems were extensively edited to match punctuation and capitalization to late 19th-century standards, with occasional rewordings to reduce Dickinson's obliquity. The first 115-poem volume was a critical and financial success, going through eleven printings in two years. ''Poems: Second Series'' followed in 1891, running to five editions by 1893; a third series appeared in 1896. One reviewer, in 1892, wrote: "The world will not rest satisfied till every scrap of her writings, letters as well as literature, has been published".

Nearly a dozen new editions of Dickinson's poetry, whether containing previously unpublished or newly edited poems, were published between 1914 and 1945. Martha Dickinson Bianchi, the daughter of Susan and Austin Dickinson, published collections of her aunt's poetry based on the manuscripts held by her family, whereas Mabel Loomis Todd's daughter, Millicent Todd Bingham

Millicent Todd Bingham (1880–1968), was an American geographer and the first woman to receive a doctorate in geology and geography from Harvard. She was also a leading expert on the poet Emily Dickinson.

Biography

Born Millicent Todd on Febr ...

, published collections based on the manuscripts held by her mother. These competing editions of Dickinson's poetry, often differing in order and structure, ensured that the poet's work was in the public's eye.

The first scholarly publication came in 1955 with a complete new three-volume set edited by Thomas H. Johnson. Forming the basis of later Dickinson scholarship, Johnson's variorum

A variorum, short for ''(editio) cum notis variorum'', is a work that collates all known variants of a text. It is a work of textual criticism, whereby all variations and emendations are set side by side so that a reader can track how textual deci ...

brought all of Dickinson's known poems together for the first time. Johnson's goal was to present the poems very nearly as Dickinson had left them in her manuscripts.Martin (2002), 17. They were untitled, only numbered in an approximate chronological sequence, strewn with dashes and irregularly capitalized, and often extremely elliptical in their language. Three years later, Johnson edited and published, along with Theodora Ward, a complete collection of Dickinson's letters, also presented in three volumes.

In 1981, ''The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson'' was published. Using the physical evidence of the original papers, the poems were intended to be published in their original order for the first time. Editor Ralph W. Franklin relied on smudge marks, needle punctures and other clues to reassemble the poet's packets. Since then, many critics have argued for thematic unity in these small collections, believing the ordering of the poems to be more than chronological or convenient.

Dickinson biographer Alfred Habegger wrote in ''My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson'' (2001) that "The consequences of the poet's failure to disseminate her work in a faithful and orderly manner are still very much with us".

Poetry

Dickinson's poems generally fall into three distinct periods, the works in each period having certain general characters in common. * Pre-1861: In the period before 1858, the poems are most often conventional and sentimental in nature. Thomas H. Johnson, who later published ''The Poems of Emily Dickinson'', was able to date only five of Dickinson's poems as written before 1858.Pickard (1967), 20. Two of these are mock valentines done in an ornate and humorous style, two others are conventional lyrics, one of which is about missing her brother Austin, and the fifth poem, which begins "I have a Bird in spring", conveys her grief over the feared loss of friendship and was sent to her friend Sue Gilbert. In 1858, Dickinson began to collect her poems in the small hand-sewn books she called fascicles. * 1861–1865: This was her most creative period, and these poems represent her most vigorous and creative work. Her poetic production also increased dramatically during this period. Johnson estimated that she composed 35 poems in 1860, 86 poems in 1861, 366 in 1862, 141 in 1863, and 174 in 1864. It was during this period that Dickinson fully developed her themes concerning nature, life, and mortality.Johnson (1960), viii. * Post-1866: Only a third of Dickinson's poems were written in the last twenty years of her life, when her poetic production slowed considerably. During this period, she no longer collected her poems in fascicles.Structure and syntax

The extensive use of

The extensive use of dash

The dash is a punctuation mark consisting of a long horizontal line. It is similar in appearance to the hyphen but is longer and sometimes higher from the baseline. The most common versions are the endash , generally longer than the hyphen ...

es and unconventional capitalization

Capitalization (American English) or capitalisation (British English) is writing a word with its first letter as a capital letter (uppercase letter) and the remaining letters in lower case, in writing systems with a case distinction. The term ...

in Dickinson's manuscripts, and the idiosyncratic

An idiosyncrasy is an unusual feature of a person (though there are also other uses, see below). It can also mean an odd habit. The term is often used to express eccentricity or peculiarity. A synonym may be "quirk".

Etymology

The term "idiosyncr ...

vocabulary and imagery, combine to create a body of work that is "far more various in its styles and forms than is commonly supposed".Hecht (1996), 153–155. Dickinson avoids pentameter, opting more generally for trimeter

In poetry, a trimeter (Greek for "three measure") is a metre of three metrical feet per line. Examples:

: When here // the spring // we see,

: Fresh green // upon // the tree.

See also

* Anapaest

* Dactyl

* Tristich

A tercet is composed of ...

, tetrameter

In poetry, a tetrameter is a line of four metrical feet. The particular foot can vary, as follows:

* '' Anapestic tetrameter:''

** "And the ''sheen'' of their ''spears'' was like ''stars'' on the ''sea''" (Lord Byron, "The Destruction of Sennach ...

and, less often, dimeter. Sometimes her use of these meters is regular, but oftentimes it is irregular. The regular form that she most often employs is the ballad stanza, a traditional form that is divided into quatrains, using tetrameter for the first and third lines and trimeter for the second and fourth, while rhyming the second and fourth lines (ABCB). Though Dickinson often uses perfect rhymes for lines two and four, she also makes frequent use of slant rhyme

Slant can refer to:

Bias

*Bias or other non- objectivity in journalism, politics, academia or other fields

Technical

* Slant range, in telecommunications, the line-of-sight distance between two points which are not at the same level

* Slant ...

.Ford (1966), 63. In some of her poems, she varies the meter from the traditional ballad stanza by using trimeter for lines one, two and four; while using tetrameter for only line three.

Since many of her poems were written in traditional ballad stanzas with ABCB rhyme schemes, some of these poems can be sung to fit the melodies of popular folk songs and hymns that also use the common meter, employing alternating lines of iambic tetrameter Iambic tetrameter is a poetic meter in ancient Greek and Latin poetry; as the name of ''a rhythm'', iambic tetrameter consists of four metra, each metron being of the form , x – u – , , consisting of a spondee and an iamb, or two iambs. The ...

and iambic trimeter.

Dickinson scholar and poet Anthony Hecht

Anthony Evan Hecht (January 16, 1923 – October 20, 2004) was an American poet. His work combined a deep interest in form with a passionate desire to confront the horrors of 20th century history, with the Second World War, in which he fought, ...

finds resonances in Dickinson's poetry not only with hymns and song-forms but also with psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

and riddles, citing the following example: "Who is the East? / The Yellow Man / Who may be Purple if he can / That carries in the Sun. / Who is the West? / The Purple Man / Who may be Yellow if He can / That lets Him out again."

Late 20th-century scholars are "deeply interested" by Dickinson's highly individual use of punctuation and lineation (line lengths and line breaks). Following the publication of one of the few poems that appeared in her lifetime – "A Narrow Fellow in the Grass", published as "The Snake" in the ''Republican'' – Dickinson complained that the edited punctuation (an added comma and a full stop substitution for the original dash) altered the meaning of the entire poem.

:

As Farr points out, "snakes instantly notice you"; Dickinson's version captures the "breathless immediacy" of the encounter; and ''The Republican''s punctuation renders "her lines more commonplace". With the increasingly close focus on Dickinson's structures and syntax has come a growing appreciation that they are "aesthetically based". Although Johnson's landmark 1955 edition of poems was relatively unaltered from the original, later scholars critiqued it for deviating from the style and layout of Dickinson's manuscripts. Meaningful distinctions, these scholars assert, can be drawn from varying lengths and angles of dash, and differing arrangements of text on the page. Several volumes have attempted to render Dickinson's handwritten dashes using many typographic symbols of varying length and angle. R. W. Franklin's 1998 variorum edition of the poems provided alternate wordings to those chosen by Johnson, in a more limited editorial intervention. Franklin also used typeset dashes of varying length to approximate the manuscripts' dashes more closely.

Major themes

Dickinson left no formal statement of her aesthetic intentions and, because of the variety of her themes, her work does not fit conveniently into any one genre. She has been regarded, alongside Emerson (whose poems Dickinson admired), as a Transcendentalist. However, Farr disagrees with this analysis, saying that Dickinson's "relentlessly measuring mind ... deflates the airy elevation of the Transcendental". Apart from the major themes discussed below, Dickinson's poetry frequently uses humor, puns,irony

Irony (), in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what on the surface appears to be the case and what is actually the case or to be expected; it is an important rhetorical device and literary technique.

Irony can be categorized int ...

and satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming o ...

.

Flowers and gardens: Farr notes that Dickinson's "poems and letters almost wholly concern flowers" and that allusions to gardens often refer to an "imaginative realm ... wherein flowers reoften emblems for actions and emotions".Farr (2005), 1–7. She associates some flowers, like gentians and anemone