Elmer Rice on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elmer Rice (born Elmer Leopold Reizenstein, September 28, 1892 – May 8, 1967) was an American playwright. He is best known for his plays ''

After writing four more plays of no special distinction, Rice startled audiences in 1923 with his next contribution to the theatre, the boldly

After writing four more plays of no special distinction, Rice startled audiences in 1923 with his next contribution to the theatre, the boldly  Rice's second hit (after ''The Adding Machine'') proved to be his most lasting literary accomplishment. Originally entitled ''Landscape with Figures,'' '' Street Scene'' (1929), later the subject of an opera by

Rice's second hit (after ''The Adding Machine'') proved to be his most lasting literary accomplishment. Originally entitled ''Landscape with Figures,'' '' Street Scene'' (1929), later the subject of an opera by  After the failure of these plays, Rice returned to Broadway in 1937 to write and direct for the Playwrights' Company, which he had helped to establish along with Maxwell Anderson, S. N. Behrman, Sidney Howard, and Robert E, Sherwood. Of his later plays, the most successful was the fantasy '' Dream Girl'' (1945) in which an over-imaginative girl encounters unexpected romance in reality. Rice's last play was ''Cue for Passion'' (1958), a modern psycho-analytical variation of the Hamlet theme in which Diana Wynyard played a Gertrude-like character. In his retirement, Rice was the author of a controversial book on American drama, ''The Living Theatre'' (1960), and of a richly detailed autobiography, ''Minority Report'' (1964).

Rice was one of the more politically outspoken dramatists of his time and took an active part in the

After the failure of these plays, Rice returned to Broadway in 1937 to write and direct for the Playwrights' Company, which he had helped to establish along with Maxwell Anderson, S. N. Behrman, Sidney Howard, and Robert E, Sherwood. Of his later plays, the most successful was the fantasy '' Dream Girl'' (1945) in which an over-imaginative girl encounters unexpected romance in reality. Rice's last play was ''Cue for Passion'' (1958), a modern psycho-analytical variation of the Hamlet theme in which Diana Wynyard played a Gertrude-like character. In his retirement, Rice was the author of a controversial book on American drama, ''The Living Theatre'' (1960), and of a richly detailed autobiography, ''Minority Report'' (1964).

Rice was one of the more politically outspoken dramatists of his time and took an active part in the

Elmer Rice Papers

at the

Elmer Rice

at answers.com *

Elmer Rice

at ''PAL: Perspectives in American Literature: A Research and Reference Guide'' * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rice, Elmer 1892 births 1967 deaths 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights Expressionist dramatists and playwrights Modernist theatre New York Law School alumni Federal Theatre Project people Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners Jewish American dramatists and playwrights Deaths from pneumonia in England 20th-century American Jews

The Adding Machine

''The Adding Machine'' is a 1923 play by Elmer Rice; it has been called "... a landmark of American Expressionism, reflecting the growing interest in this highly subjective and nonrealistic form of modern drama." Plot

The author of this play ta ...

'' (1923) and his Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made ...

-winning drama of New York tenement life, '' Street Scene'' (1929).

Biography

Early years

Rice was born Elmer Leopold Reizenstein at 127 East 90th Street in New York City. His grandfather was a political activist in theRevolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europ ...

in the German states. After the failure of that political upheaval, he emigrated to the United States where he became a businessman. He spent most of his retirement years living with the Rice family and developed a close relationship with his grandson Elmer, who became a politically motivated writer and shared his grandfather's liberal and pacifist politics. A staunch atheist, his grandfather may also have influenced Elmer in his feelings about religion as he refused to attend Hebrew school or to have a bar mitzvah. In contrast, Rice's relationship with his father was very distant. As he wrote in his autobiography, his grandfather and his Uncle Will, both of whom boarded with the family, made up for the affection and attention his father withheld. A child of the tenements, Rice spent much of his youth reading, to his family's consternation, and later observed, "Nothing in my life has been more helpful than the simple act of joining the library."

Because of his need to support his family when his father's epilepsy worsened, Rice did not complete high school, and he took a number of menial jobs before earning his diploma by preparing for the state examinations on his own and then applying to law school. Though he disliked legal studies and spent a good deal of class time reading plays in class (because they could be finished within the span of a two-hour lecture, he said), Rice graduated from New York Law School

New York Law School (NYLS) is a private law school in Tribeca, New York City. NYLS has a full-time day program and a part-time evening program. NYLS's faculty includes 54 full-time and 59 adjunct professors. Notable faculty members include ...

in 1912 and began a short-lived legal career. Leaving the profession in 1914, he was always to retain a cynical outlook about lawyers, but his two years in a law office provided him with material for several plays, most notably ''Counsellor-at-Law'' (1931). Courtroom dramas became a Rice specialty.

Needing to make a living, he decided to try writing full-time. It was a wise decision. His first play, ''On Trial'' (1914), a melodramatic murder mystery, was a great success and ran for 365 performances in New York. George M. Cohan offered to buy the rights for $30,000, a proposition Rice declined largely because he did not believe Cohan could be serious. Co-authored with a friend, Frank Harris (not the famed Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

biographer), the play was purportedly the first American drama to employ the technique of reverse-chronology, telling the story from its conclusion to its starting-point. ''On Trial'' then went on tour throughout the United States with three separate companies and was produced in Argentina, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Mexico, Norway, Scotland and South Africa. The author ultimately earned $100,000 from his first work for the stage. None of his later plays earned him as much as ''On Trial.'' The play was adapted for the cinema three times, in 1917, 1928, and 1939.

Political and social issues occupied Rice's attention in this period as well. World War I and Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's conservatism confirmed him in his criticism of the status quo. (He had been firmly converted to socialism in his teens, he said, by reading George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, H.G. Wells, John Galsworthy

John Galsworthy (; 14 August 1867 – 31 January 1933) was an English novelist and playwright. Notable works include '' The Forsyte Saga'' (1906–1921) and its sequels, ''A Modern Comedy'' and ''End of the Chapter''. He won the Nobel Prize ...

, Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and social ...

, Frank Norris

Benjamin Franklin Norris Jr. (March 5, 1870 – October 25, 1902) was an American journalist and novelist during the Progressive Era, whose fiction was predominantly in the naturalist genre. His notable works include '' McTeague: A Story of Sa ...

, and Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

.) He frequented Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

, then the most bohemian part of New York City, in the late 1910s and became friendly with many socially conscious writers and activists, including the African-American poet James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871June 26, 1938) was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peop ...

and the illustrator Art Young

Arthur Henry Young (January 14, 1866 – December 29, 1943) was an American cartoonist and writer. He is best known for his socialist cartoons, especially those drawn for the left-wing political magazine '' The Masses'' between 1911 and 1917.

...

.

Career

After writing four more plays of no special distinction, Rice startled audiences in 1923 with his next contribution to the theatre, the boldly

After writing four more plays of no special distinction, Rice startled audiences in 1923 with his next contribution to the theatre, the boldly expressionistic

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it r ...

''The Adding Machine

''The Adding Machine'' is a 1923 play by Elmer Rice; it has been called "... a landmark of American Expressionism, reflecting the growing interest in this highly subjective and nonrealistic form of modern drama." Plot

The author of this play ta ...

'', which he wrote in 17 days. A satire about the growing regimentation of life in the machine age, the play tells the story of the life, death and bizarre afterlife of a dull bookkeeper, Mr. Zero. When Mr. Zero, a mere cog in the corporate machine, discovers that he is to be replaced at work by an adding machine

An adding machine is a class of mechanical calculator, usually specialized for bookkeeping calculations.

In the United States, the earliest adding machines were usually built to read in dollars and cents. Adding machines were ubiquitous off ...

, he snaps and murders his boss. After his trial and execution, he enters the next life only to confront some of the same issues and, judged to be of minimal use in heaven, is sent back to Earth for recycling. Theatre critic Brooks Atkinson

Justin Brooks Atkinson (November 28, 1894 – January 14, 1984) was an American theatre critic. He worked for '' The New York Times'' from 1922 to 1960. In his obituary, the ''Times'' called him "the theater's most influential reviewer of hi ...

called it "the most original and brilliant play any American had written up to that time ... the harshest and most illuminating play about modern society roadway had ever seen" Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker (née Rothschild; August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet, writer, critic, and satirist based in New York; she was known for her wit, wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles.

From a conflicted and unhap ...

and Alexander Woollcott

Alexander Humphreys Woollcott (January 19, 1887 – January 23, 1943) was an American drama critic and commentator for ''The New Yorker'' magazine, a member of the Algonquin Round Table, an occasional actor and playwright, and a prominent radio p ...

were enthusiastic. Other reviewers spoke of him, hyperbolically, as a writer who might become America's Ibsen. Directed with great ingenuity by Philip Moeller

Philip Moeller (26 August 1880 – 26 April 1958) was an American stage producer and director, playwright and screenwriter, born in New York where he helped found the short-lived Washington Square Players and then with Lawrence Langner and Hele ...

, designed by Lee Simonson

Lee Simonson (June 26, 1888, New York City – January 23, 1967, Yonkers) was an American architect painter, stage setting designer.

He acted as a stage set designer for the Washington Square Players (1915–1917). When it became the Theatre Gu ...

, and produced by the Theatre Guild

The Theatre Guild is a theatrical society founded in New York City in 1918 by Lawrence Langner, Philip Moeller, Helen Westley and Theresa Helburn. Langner's wife, Armina Marshall, then served as a co-director. It evolved out of the work of th ...

, the play starred Dudley Digges (actor)

Dudley Digges (born John Dudley Digges, 9 June 1879 – 24 October 1947) was an Irish stage actor, director, and producer as well as a film actor. Although he gained his initial theatre training and acting experience in Ireland, the vast maj ...

and Edward G. Robinson

Edward G. Robinson (born Emanuel Goldenberg; December 12, 1893January 26, 1973) was a Romanian-American actor of stage and screen, who was popular during the Hollywood's Golden Age. He appeared in 30 Broadway plays and more than 100 films duri ...

, then at the start of his acting career. Ironically, it made its author no money at all. (Adapted as an innovatively staged musical in 2007, ''The Adding Machine'' enjoyed a successful Off-Broadway run in 2008.)

When Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker (née Rothschild; August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet, writer, critic, and satirist based in New York; she was known for her wit, wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles.

From a conflicted and unhap ...

was at work on her play the following year (loosely based on fellow Algonquin Round Table

The Algonquin Round Table was a group of New York City writers, critics, actors, and wits. Gathering initially as part of a practical joke, members of "The Vicious Circle", as they dubbed themselves, met for lunch each day at the Algonquin Hotel ...

member Robert Benchley

Robert Charles Benchley (September 15, 1889 – November 21, 1945) was an American humorist best known for his work as a newspaper columnist and film actor. From his beginnings at '' The Harvard Lampoon'' while attending Harvard University, thr ...

, his marital problems, and the extra-marital temptations he was grappling with) and needed a co-author, she approached Elmer Rice, now acknowledged as the Broadway "boy wonder" of the moment. It was a smooth collaboration and resulted in a brief affair between Parker and the already-married Rice, begun at Rice's insistent urging. The run of the play did not go smoothly, however; despite good reviews, ''Close Harmony'' (1924) closed quickly and was forgotten.

Rice was a prolific, even tireless writer. His plays over the next five years included the unproduced ''The Sidewalks of New York'' (1925), ''Is He Guilty?'' (1927) and ''The Gay White Way'' (1928) and two collaborations, ''Wake Up, Jonathan'' (1928) with Hatcher Hughes, a dramatist unknown today and ''Cock Robin'' (1929) with Philip Barry, a Broadway name equal to Rice's. None of these plays were a success. Rice was a theatre professional by this time: open to collaboration, increasingly interested in producing and directing his own plays. In the 1930s, he even bought a Broadway house, the famed Belasco Theatre

The Belasco Theatre is a Broadway theater at 111 West 44th Street, between Seventh Avenue and Sixth Avenue, in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. Originally known as the Stuyvesant Theatre, it was built in 1907 a ...

.

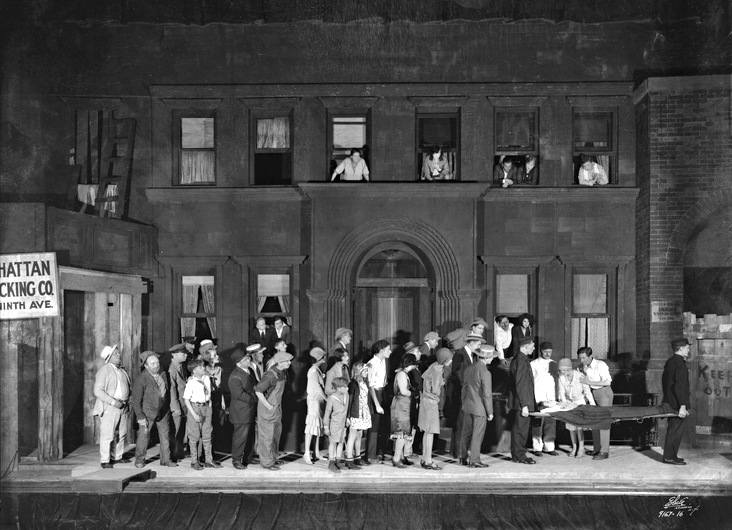

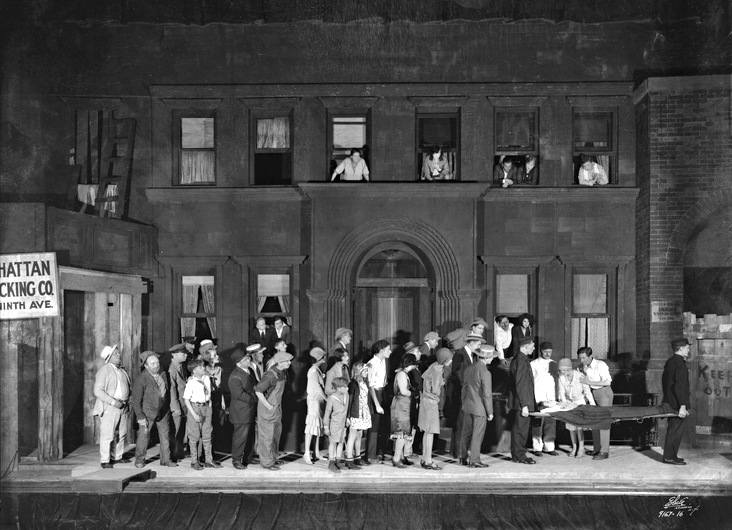

Rice's second hit (after ''The Adding Machine'') proved to be his most lasting literary accomplishment. Originally entitled ''Landscape with Figures,'' '' Street Scene'' (1929), later the subject of an opera by

Rice's second hit (after ''The Adding Machine'') proved to be his most lasting literary accomplishment. Originally entitled ''Landscape with Figures,'' '' Street Scene'' (1929), later the subject of an opera by Kurt Weill

Kurt Julian Weill (March 2, 1900April 3, 1950) was a German-born American composer active from the 1920s in his native country, and in his later years in the United States. He was a leading composer for the stage who was best known for his fru ...

, won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama

The Pulitzer Prize for Drama is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It is one of the original Pulitzers, for the program was inaugurated in 1917 with seven prizes, four of which were a ...

for its realistic chronicle of life in the slums. "With fifty characters casually strolling through it," Brooks Atkinson wrote, "it looked like an improvisation...Based on the facade of a house at 25 West 65th Street, which Rice selected as typical, the tall massive setting caught the tone and humanity of a decaying brownstone." The script had been rejected by most producers who read it, and director George Cukor

George Dewey Cukor (; July 7, 1899 – January 24, 1983) was an American film director and film producer. He mainly concentrated on comedies and literary adaptations. His career flourished at RKO when David O. Selznick, the studio's Head ...

abandoned it as un-stageable after the second day of rehearsals. Rice took over the direction himself and proved that it was highly stageworthy, if unconventional in its narrative style and disorienting naturalism. Like ''The Adding Machine,'' the play's break with the conventions of stage realism was part of its appeal.

Rice's plays of the 1930s included ''The Left Bank'' (1931), a comedy dramatizing an expatriate's superficial attempt to escape from American materialism in Paris, and ''Counsellor-at-Law'' (1931), a vigorous work that drew a realistic picture of the legal profession for which Rice had been trained. (The latter play is probably more frequently revived in regional theatres than any of Rice's other plays.) In that decade, he also wrote two novels and enjoyed a lucrative period in Hollywood, writing screenplays. His time in Hollywood was not without its friction, though, as he was looked upon by many studio heads as one of "those Eastern Reds."

The Depression-inspired, anti-capitalist ''We, the People'' (1933) was a play particularly close to Rice's heart. It dealt with "the misfortunes of a typical skilled workman and his family, helplessly engulfed in the tide of national adversity," as its author described it. Rice engaged an activist-minded cast and noted set designer Aline Bernstein to design the fifteen different sets that the ambitious play called for. ''We, the People'' failed amid what Rice called "agitated" reviews. A 1932 trip to the Soviet Union and to Germany, where he heard Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

speak, provided material for Rice's next plays. The Reichstag fire trial is an element in ''Judgement Day'' (1934), and conflicting American and Soviet ideologies form the subject of the conversation-piece ''Between Two Worlds'' (1934).

After the failure of these plays, Rice returned to Broadway in 1937 to write and direct for the Playwrights' Company, which he had helped to establish along with Maxwell Anderson, S. N. Behrman, Sidney Howard, and Robert E, Sherwood. Of his later plays, the most successful was the fantasy '' Dream Girl'' (1945) in which an over-imaginative girl encounters unexpected romance in reality. Rice's last play was ''Cue for Passion'' (1958), a modern psycho-analytical variation of the Hamlet theme in which Diana Wynyard played a Gertrude-like character. In his retirement, Rice was the author of a controversial book on American drama, ''The Living Theatre'' (1960), and of a richly detailed autobiography, ''Minority Report'' (1964).

Rice was one of the more politically outspoken dramatists of his time and took an active part in the

After the failure of these plays, Rice returned to Broadway in 1937 to write and direct for the Playwrights' Company, which he had helped to establish along with Maxwell Anderson, S. N. Behrman, Sidney Howard, and Robert E, Sherwood. Of his later plays, the most successful was the fantasy '' Dream Girl'' (1945) in which an over-imaginative girl encounters unexpected romance in reality. Rice's last play was ''Cue for Passion'' (1958), a modern psycho-analytical variation of the Hamlet theme in which Diana Wynyard played a Gertrude-like character. In his retirement, Rice was the author of a controversial book on American drama, ''The Living Theatre'' (1960), and of a richly detailed autobiography, ''Minority Report'' (1964).

Rice was one of the more politically outspoken dramatists of his time and took an active part in the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

, the Authors' League, the Dramatists Guild of America where he was elected as the eighth president in 1939, and P.E.N. He was the first director of the New York office of the Federal Theatre Project

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP; 1935–1939) was a theatre program established during the Great Depression as part of the New Deal to fund live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United States. It was one of five Federal Pro ...

, but resigned in 1936 to protest government censorship of the Project's "Living Newspaper

Living Newspaper is a term for a theatrical form presenting factual information on current events to a popular audience. Historically, Living Newspapers have also urged social action (both implicitly and explicitly) and reacted against naturali ...

" dramatization of Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia. An outspoken defender of free speech, he left that position with a "blast of scorn" at the Roosevelt administration's efforts to control artistic expression. (In 1932, Rice reluctantly supported the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

candidate in the presidential election because he found Hoover

Hoover may refer to:

Music

* Hoover (band), an American post-hardcore band

* Hooverphonic, a Belgian band originally named Hoover

* Hoover (singer), Willis Hoover, a country and western performer active in 1960s and '70s

* "Hoover" (song), a 2016 ...

and Roosevelt equally displeasing alternatives with an insufficient grasp of the crisis the country faced. though in subsequent elections he became an FDR supporter) He also spoke out against McCarthyism in the 1950s.

In the end, Elmer Rice did not believe he had been a success as a writer, not as he wished to define success. He needed to make a living and, while deriding the commercialism of the New York stage, he managed to earn a considerable amount of money, but at a cost to his more experimental vision. The realistic drama he could write with ease was at odds with the innovations that most intrigued him. ''The Adding Machine'' and ''Street Scene'' were anomalies and did not make money. An even more radical venture, ''The Sidewalks of New York'' of 1925, was an episodic play without words, "in which speech is indicated by gesture, by a series of situations in which there was no need for speech." The Theatre Guild turned the script down flat; Broadway would never be ready for the level of experimentation that inspired Rice, a reality that was a source of continuous frustration for him.

Personal life

Rice was married in 1915 to Hazel Levy and had two children with her, Margaret and Robert. After his divorce in 1942, he married actressBetty Field

Betty Field (February 8, 1916 – September 13, 1973) was an American film and stage actress.

Early years

Field was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to George and Katharine (née Lynch) Field. She began acting before she reached age 15, and went ...

with whom he had three children, John, Judy and Paul. Field and Rice divorced in 1956.

Alhough born into a working-class family with no interest in the arts and known primarily for his attachment to theater and politics, Rice was passionate about Old Master and modern art. His art collection, slowly assembled over the years, included works by Picasso, Braque, Rouault, Leger, Derain, Klee, and Modigliani. He regularly frequented New York's museums, and in his autobiography, wrote of his first trip to Spain and the powerful impact Velazquez had on him and, in Mexico, of enjoying the work of Diego Rivera and the Mexican Muralists, artists who shared his political views. He was close friends with Japanese-American modernist painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi.

Elmer Rice lived for many years on a wooded estate in Stamford, Connecticut until his death in Southampton, England in 1967 of pneumonia after suffering a heart attack. Obituaries took note of a long and respected theater career. Brooks Atkinson described Rice in his history of Broadway as "a plain, rather sober man with a reticent, unyielding personality...But when a social principle was at stake, he was more clear-headed than most people, and he was quietly invincible...He was one of Broadway's most eminent citizens."

Archive

Elmer Rice's papers were placed at theHarry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pur ...

at the University of Texas at Austin in 1968, a year after his death. Additions have been made by family members over the years. The collection spans over 100 boxes and includes contracts, correspondence, manuscript drafts, notebooks, photographs, royalty statements, scripts, theater programs, and over seventy-three scrapbooks. The Ransom Center's library division has over 900 books from Rice's personal library, many of which are personally inscribed to or annotated by Rice.

Film portrayal

Rice was portrayed by the actorJon Favreau

Jonathan Kolia Favreau (; born October 19, 1966) is an American actor and filmmaker. As an actor, Favreau has appeared in films such as '' Rudy'' (1993), '' PCU'' (1994), '' Swingers'' (1996), ''Very Bad Things'' (1998), '' Deep Impact'' (1998) ...

in the 1994 film ''Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle

''Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle'' is a 1994 American biographical drama film directed by Alan Rudolph from a screenplay written by Rudolph and Randy Sue Coburn. The film stars Jennifer Jason Leigh as writer Dorothy Parker and depicts the mem ...

''.

Stage productions

* ''A Defection from Grace'' with Frank Harris (1913, unpublished) * ''The Seventh Commandment'' with Frank Harris (1913, unpublished) * ''The Passing of Chow-Chow'' (1913, one act, published in 1925) * ''On Trial'' (1914) with Frank Harris * ''The Iron Cross'' (1917) * ''The Home of the Free'' (1918) * ''For the Defense'' (1919) * ''It Is the Law'' (1922) * ''The Adding Machine

''The Adding Machine'' is a 1923 play by Elmer Rice; it has been called "... a landmark of American Expressionism, reflecting the growing interest in this highly subjective and nonrealistic form of modern drama." Plot

The author of this play ta ...

'' (1923)

* ''The Mongrel'' (1924) from a novel by Hermann Bahr

* ''Close Harmony'' (with Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker (née Rothschild; August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet, writer, critic, and satirist based in New York; she was known for her wit, wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles.

From a conflicted and unhap ...

, 1924)

* ''The Sidewalks of New York'' (1925, unpublished in 1925, published in 1934 as ''Three Plays Without Words'')

* ''Is He Guilty?'' (1927)

* ''Wake Up, Jonathan'' with Hatcher Hughes

Hatcher Hughes (12 February 1881, Polkville, North Carolina – 19 October 1945, New York City) was an American playwright who lived in Grover, NC, as featured in the book ''Images of America''. He was on the teaching staff of Columbia Un ...

(1928)

* ''The Gay White Way'' (1928)

* ''Cock Robin'' with Philip Barry

Philip Jerome Quinn Barry (June 18, 1896 – December 3, 1949) was an American dramatist best known for his plays ''Holiday'' (1928) and '' The Philadelphia Story'' (1939), which were both made into films starring Katharine Hepburn and Cary Gran ...

(1929)

* '' Street Scene'' (1929, also directed)

* ''The Subway'' (1929)

* ''See Naples and Die'' (1930, also directed)

* ''The Left Bank'' (1931, also produced and directed)

* ''Counsellor-at-Law'' (1931, also produced and directed)

* ''The House in Blind Alley: A Play in Three Acts'' (1932)

* ''We, the People'' (1933, also produced and directed)

* ''Three Plays Without Words'' (1934, one act)

** ''Landscape with Figures''

** ''Rus in Urbe''

** ''Exterior''

* ''The Home of the Free'' (1934, one act)

* ''Judgment Day'' (1934, also produced and directed)

* ''Two Plays'' (1935)

** ''Between Two Worlds'' (also produced and directed)

** '' Not for Children''

* ''Black Sheep'' (1938, also produced and directed)

* ''American Landscape'' (1938, also directed)

* ''Two On an Island'' (1940, also directed)

* ''Flight to the West'' (1940, also directed)

* '' The Talley Method'' (1941, also produced and directed)

* ''A New Life'' (1944)

* '' Dream Girl'' (1946, also directed)

* ''The Grand Tour'' (1952, also directed)

* ''The Winner'' (1954, also directed)

* ''Cue for Passion'' (1959, also directed)

* ''Love Among the Ruins'' (1963)

* ''Court of Last Resort'' (1965)

Novels

* ''On Trial'' (1915, a novelization of the play) * ''Papa Looks for Something'' (unpublished, 1926) * ''A Voyage to Purilia'' (1930), serialized in the ''New Yorker'' in 1929 * ''Imperial City'' (1937) *''The Show Must Go On'' (1949)Non-fiction

* "The Playwright as Director," ''Theatre Arts Monthly 13'' (May 1929): pp. 355–360 * "Organized Charity Turns Censor," ''Nation'' 132 (June 10, 1931) pp. 628–630 * "The Joys of Pessimism," ''Forum'' 86 (July 1931) pp. 33–35 * "Sex in the Modern Theatre," ''Harper's'' 164 (May 1932) pp. 665–673 * "Theatre Alliance: A Cooperative Repertory Project," ''Theatre Arts Monthly'' 19 (June 1935) pp. 427–430 * "The Supreme Freedom" (1949) (pamphlet) * "Conformity in the Arts" (1953) (pamphlet) * "Entertainment in the Age of McCarthy," ''New Republic'' 176 (April 13, 1953) pp. 14–17 * ''The Living Theatre'' (1959) * ''Minority Report'' (1964) * "Author! Author!" ''American Heritage'' 16 (April 1965) pp 46–49, 84-86Selected filmography (play adaptations)

*1917: ''On Trial'' *1922: '' For the Defense'' *1924: ''It Is the Law

''It Is the Law'' is a 1924 American silent mystery film directed by J. Gordon Edwards and starring Arthur Hohl, Herbert Heyes, and Mona Palma. It is a film adaptation of the 1922 Broadway play of the same name by Elmer Rice, itself based ...

''

*1928: '' On Trial''

*1930: ''Oh Sailor Behave

''Oh, Sailor, Behave!'' is a 1930 American Pre-Code musical comedy film produced and released by Warner Brothers, and based on the play ''See Naples and Die'', written by Elmer Rice. The film was originally intended to be entirely in Technicolor ...

''

*1931: '' Street Scene''

*1933: ''Counsellor at Law

''Counsellor at Law'' is a 1933 American pre-Code drama film directed by William Wyler. The screenplay by Elmer Rice is based on his 1931 Broadway play of the same title.

Plot

The story focuses on several days in a critical juncture in the lif ...

''

*1939: '' On Trial''

*1948: '' Dream Girl''

*1969: ''The Adding Machine

''The Adding Machine'' is a 1923 play by Elmer Rice; it has been called "... a landmark of American Expressionism, reflecting the growing interest in this highly subjective and nonrealistic form of modern drama." Plot

The author of this play ta ...

''

Other writing

*1921: ''Doubling for Romeo'' (scenario) *1922: ''Rent Free'' (scenario) *1942: ''Holiday Inn

Holiday Inn is an American chain of hotels based in Atlanta, Georgia. and a brand of IHG Hotels & Resorts. The chain was founded in 1952 by Kemmons Wilson, who opened the first location in Memphis, Tennessee that year. The chain was a division ...

'' (adaptation)

References

Sources

*Atkinson, Brooks. ''Broadway.'' New York: Atheneum, 1970. *Durham, Frank. ''Elmer Rice.'' Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1970. *Hogan, Robert. ''The Independence of Elmer Rice.'' New York: Twayne, 1965. *Palmieri, Anthony. ''Elmer Rice: A Playwright's Vision of America.'' Madison, NJ: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1980. *Rice, Elmer. ''Minority Report.'' New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963.External links

Elmer Rice Papers

at the

Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pur ...

*

*

*

*

*

Elmer Rice

at answers.com *

Elmer Rice

at ''PAL: Perspectives in American Literature: A Research and Reference Guide'' * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rice, Elmer 1892 births 1967 deaths 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights Expressionist dramatists and playwrights Modernist theatre New York Law School alumni Federal Theatre Project people Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners Jewish American dramatists and playwrights Deaths from pneumonia in England 20th-century American Jews