Edward Sylvester Morse on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

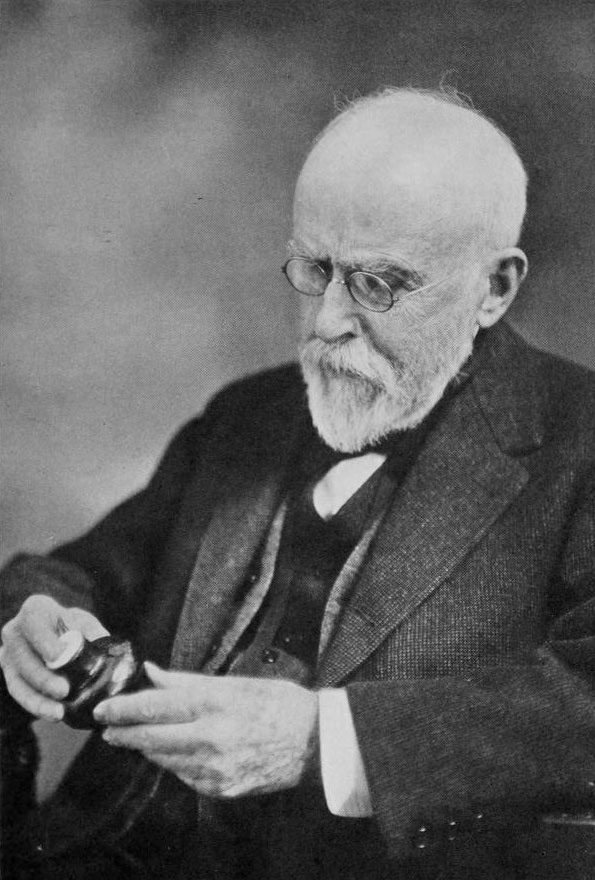

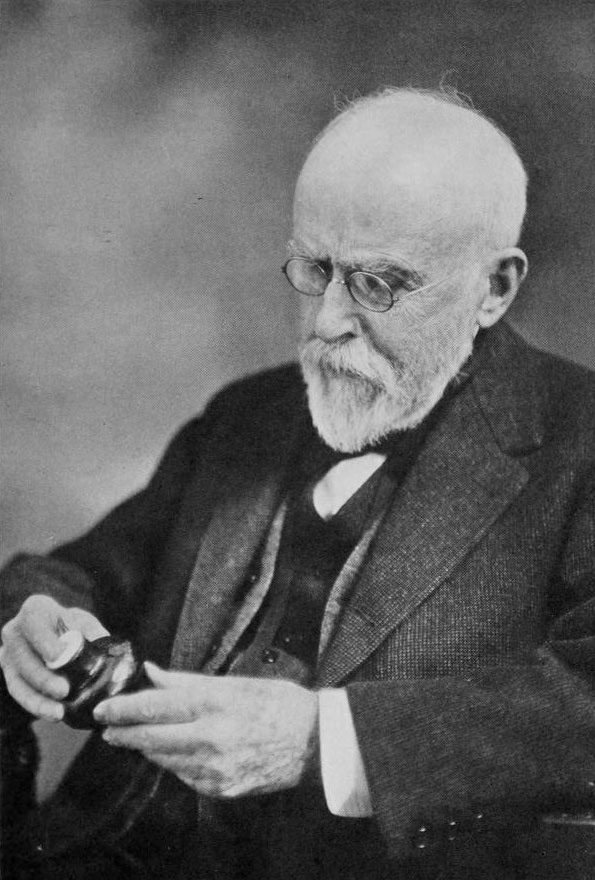

Edward Sylvester Morse (June 18, 1838 – December 20, 1925) was an American

He was a gifted draughtsman, a skill that served him well throughout his career. As a young man, it enabled him to be employed as a mechanical draughtsman at the Portland Locomotive Company and later preparing wood engravings for natural history publications. This relatively well-paid work enabled him to save enough money to support his further education. Morse was recommended by

He was a gifted draughtsman, a skill that served him well throughout his career. As a young man, it enabled him to be employed as a mechanical draughtsman at the Portland Locomotive Company and later preparing wood engravings for natural history publications. This relatively well-paid work enabled him to save enough money to support his further education. Morse was recommended by

Morse rapidly became successful in the field of zoology, specializing in

Morse rapidly became successful in the field of zoology, specializing in  In 1867, along with Putnam, Hyatt and Packard, Morse co-founded the scientific journal ''

In 1867, along with Putnam, Hyatt and Packard, Morse co-founded the scientific journal '' From 1871 to 1874, Morse was appointed to the chair of comparative anatomy and zoology at

From 1871 to 1874, Morse was appointed to the chair of comparative anatomy and zoology at

After leaving Japan, Morse traveled to Southeast Asia and Europe. In subsequent years, he returned to Europe, and Japan in quest of pottery.

In 1886 Morse became president of the

After leaving Japan, Morse traveled to Southeast Asia and Europe. In subsequent years, he returned to Europe, and Japan in quest of pottery.

In 1886 Morse became president of the

''First Book of Zoölogy''

New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1, 3, and 5 Bond Street

Second Edition, 1886

* 1885

''Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings.''

New York:

OCLC 3050569

* 189

''On the Older Forms of Terra-cotta Roofing Tiles''

Bulletin of the Essex Institute 24: 1-72 * 189

''Latrines of the East''

The American Architect and Building News 39: 170-174 * 1901

''Catalogue of the Morse collection of Japanese pottery''

Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press. * 1902

''Glimpses of China and Chinese Homes.''

Boston:

OCLC 1116550

* 1917. ''Japan Day by Day, 1877, 1878-79, 1882-83.'' Boston:

OCLC 412843 ''Volume I. ''Volume II.

''The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics, and the Opening of Old Japan,''

New York:

OCLC 50511058

* Rosenstone, Robert A. (1988)

''Mirror in the Shrine: American Encounters with Meiji Japan.''

Cambridge:

OCLC 17108604

* Wayman, Dorothy Godfrey. (1942) ''Edward Sylvester Morse: A Biography.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press

OCLC 757515

* 2018. ''From Morse to Whyte: A Dynastic Bequest of Japanese Treasures''. Catalogue published by the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Banff, AB. Canada

"Japanese Ceramics from the Collection of Edward Sylvester Morse."

* * * Whyte Museum {{DEFAULTSORT:Morse, Edward S. American anthropologists American expatriates in Japan American curators American zoologists Foreign advisors to the government in Meiji-period Japan Foreign educators in Japan Museum of Fine Arts, Boston People from Portland, Maine 1838 births 1925 deaths Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Treasure University of Tokyo faculty Burials at Harmony Grove Cemetery Members of the American Antiquarian Society

zoologist

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

, archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

, and orientalist. He is considered the "Father of Japanese archaeology."

Early life

Morse was born inPortland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

, Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

to Jonathan Kimball Morse and Jane Seymour (Becket) Morse. His father was a Congregationalist deacon who held strict Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

beliefs. His mother, who did not share her husband's religious beliefs, encouraged her son's interest in the sciences. An unruly student, Morse was expelled from all but one of the schools he attended in his youth — the Portland village school, the academy at Conway, New Hampshire

Conway is a town in Carroll County, New Hampshire, United States. It is the most populous community in the county, with a population of 9,822 at the 2020 census, down from 10,115 at the 2010 census. The town is on the southeastern edge of the Whi ...

, in 1851, and Bridgton Academy in 1854 (for carving on desks). He also attended Gould Academy

Gould Academy is a private, co-ed, college preparatory boarding and day school founded in 1836 and located in the small town of Bethel, Maine, United States.

History

In 1835 citizens of Bethel, Maine, formed an organization as trustees of the ...

in Bethel, Maine

Bethel is a town in Oxford County, Maine, United States. The population was 2,504 at the 2020 census. It includes the villages of Bethel and West Bethel. The town is home to Gould Academy, a private preparatory school, and is near the Sun ...

. At Gould Academy, Morse came under the influence of Dr. Nathaniel True who encouraged Morse to pursue his interest in the study of nature.

He preferred to explore the Atlantic coast in search of shells and snails, or go to the field to study the fauna and flora. By the age of thirteen he had put together an impressive collection of shells. Despite his lack of formal education, his collections soon earned him the visit of eminent scientists from Boston, Washington and even the United Kingdom. He was noted for his work with land snails, and discovered two new species: ''Helix asteriscus'', now known as '' Planogyra asteriscus'', and ''H. Milium'', now known as '' Striatura milium''. These species were presented at meetings of the Boston Society of Natural History in 1857 and 1859.

He was a gifted draughtsman, a skill that served him well throughout his career. As a young man, it enabled him to be employed as a mechanical draughtsman at the Portland Locomotive Company and later preparing wood engravings for natural history publications. This relatively well-paid work enabled him to save enough money to support his further education. Morse was recommended by

He was a gifted draughtsman, a skill that served him well throughout his career. As a young man, it enabled him to be employed as a mechanical draughtsman at the Portland Locomotive Company and later preparing wood engravings for natural history publications. This relatively well-paid work enabled him to save enough money to support his further education. Morse was recommended by Philip Pearsall Carpenter

Philip Pearsall Carpenter (4 November 1819 – 24 May 1877) was an English minister who emigrated to Canada, where his field work as a malacologist or conchologist is still well regarded today. A man of many talents, he wrote, published, taught, ...

to Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he rec ...

(1807–1873) at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

for his intellectual qualities and talent at drawing. After completing his studies he served as Agassiz's assistant in charge of conservation, documentation and drawing collections of mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

s and brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, w ...

s until 1862. He became especially interested in brachiopods during this time, and his first paper on the topic was published in 1862.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Morse attempted to enlist in the 25th Maine Infantry, but was turned down due to a chronic tonsil infection. On June 18, 1863, Morse married Ellen (“Nellie”) Elizabeth Owen in Portland. The couple had two children, Edith Owen Morse and John Gould Morse (named after Morse's lifelong friend Major John Mead Gould).

Career

Morse rapidly became successful in the field of zoology, specializing in

Morse rapidly became successful in the field of zoology, specializing in malacology

Malacology is the branch of invertebrate zoology that deals with the study of the Mollusca (mollusks or molluscs), the second-largest phylum of animals in terms of described species after the arthropods. Mollusks include snails and slugs, clams, ...

or the study of molluscs. In 1864, he published his first work devoted to molluscs under the title ''Observations On The Terrestrial Pulmonifera of Maine''. Morse had been elected to the position of curator of the Portland Natural History Society, a position he hoped would become permanent. But in 1866 the Great Fire destroyed the buildings of the Society, along with much of Portland, and also the chance of a salaried position. An alternative opportunity arose with the foundation of the Peabody Academy of Science in Salem. Morse returned to Massachusetts to work at the academy, along with Caleb Cooke, Alpheus Hyatt

Alpheus Hyatt (April 5, 1838 – January 15, 1902) was an American zoologist and palaeontologist.

Biography

Alpheus Hyatt II was born in Washington, D.C. to Alpheus Hyatt and Harriet Randolph (King) Hyatt. He briefly attended the Maryla ...

, Alpheus Spring Packard

Alpheus Spring Packard Jr. LL.D. (February 19, 1839 – February 14, 1905) was an American entomologist and palaeontologist. He described over 500 new animal species – especially butterflies and moths – and was one of the founders of ''The Am ...

and Frederic Ward Putnam

Frederic Ward Putnam (April 16, 1839 – August 14, 1915) was an American anthropologist and biologist.

Biography

Putnam was born and raised in Salem, Massachusetts, the son of Ebenezer (1797–1876) and Elizabeth (Appleton) Putnam. After leavin ...

(director), all former students of Agassiz.

In 1867, along with Putnam, Hyatt and Packard, Morse co-founded the scientific journal ''

In 1867, along with Putnam, Hyatt and Packard, Morse co-founded the scientific journal ''The American Naturalist

''The American Naturalist'' is the monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal of the American Society of Naturalists, whose purpose is "to advance and to diffuse knowledge of organic evolution and other broad biological principles so as to enhance th ...

'', and Morse became one of its editors. The establishment of the Journal was very important for American Natural History. It was written by experts in the field, but aimed to be accessible to a wide readership. This aim was greatly helped by the high quality of the illustrations, many of them provided by Morse himself. Morse's desire to bring natural history to a wider audience also led him to give lectures to a variety of audiences. His combination of broad knowledge, speaking skill, and ability to draw quickly on the blackboard with both hands made him a popular presenter.

Morse continued his work on brachiopods, often considered to be his most important scientific work. Between 1869 and 1873 he published a series of papers on the embryology and classification of the group. Whereas in 1865 he had accepted the majority view that placed brachiopoda within the molluscs, in 1870 largely on the basis of embryological observations, he proposed that the brachiopoda should be removed from the molluscs, and placed within the annelids

The annelids (Annelida , from Latin ', "little ring"), also known as the segmented worms, are a large phylum, with over 22,000 extant species including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to various ecolo ...

, a group of segmented worms. Modern taxonomy agrees with the first of these propositions, but not the second, classifying molluscs, brachiopods and annelids as three separate phyla within the superphylum Lophotrochozoa

Lophotrochozoa (, "crest/wheel animals") is a clade of protostome animals within the Spiralia. The taxon was established as a monophyletic group based on molecular evidence. The clade includes animals like annelids, molluscs, bryozoans, brachi ...

. Helen Muir-Wood has given an account of the history of the classification of the brachiopods that places Morse's work in its historical context.

From 1871 to 1874, Morse was appointed to the chair of comparative anatomy and zoology at

From 1871 to 1874, Morse was appointed to the chair of comparative anatomy and zoology at Bowdoin College

Bowdoin College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Brunswick, Maine. When Bowdoin was chartered in 1794, Maine was still a part of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The college offers 34 majors and 36 minors, as well as several joint eng ...

. In 1873 and 1874 he was a teacher at the summer school established by Agassiz on Penikese Island

Penikese Island is a island off the coast of Massachusetts, United States, in Buzzards Bay. It is one of the Elizabeth Islands, which make up the town of Gosnold, Massachusetts. Penikese is located near the west end of the Elizabeth island cha ...

. Though the school only operated for a few years, several of its students went on to distinguished careers, including David Starr Jordan

David Starr Jordan (January 19, 1851 – September 19, 1931) was the founding president of Stanford University, serving from 1891 to 1913. He was an ichthyologist during his research career. Prior to serving as president of Stanford Univer ...

. In 1874, he became a lecturer at Harvard University. In 1876, Morse was named a fellow of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

. In 1877, he provided the illustrations for a book by his friend John Mead Gould, entitled ''How to camp out''.Gould, John M.

During this period the issue of evolution caused much discussion and controversy. Agassiz was an opponent of evolution. He argued that the persistence of animals such as '' Lingula'' (a brachiopod) over immense periods of time, from the Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the shortest period of the Paleozo ...

to the present day, with little change was "a fatal objection to the theory of gradual development". However all of his students subsequently adopted evolutionary theory in various forms. A clear statement of Morse's position on evolution is found in his address, as vice-president (Natural History) of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is an American international non-profit organization with the stated goals of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific respons ...

at its Buffalo NY meeting in August 1876 (reprinted under the title of ''What American Zoologists have done for Evolution'') He adopts a clear selectionist position, in contrast, for example, to Hyatt, who was a neo-Lamarckian. He addresses the issue of human origins, and finds the evidence for "the lowly origin of man", and common ancestry with apes, convincing. He did not only express these views in a western context, but was subsequently the first to bring Darwin's theory of evolution to Japan.

Japan

In June 1877 Morse first visitedJapan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

in search of coastal brachiopods. His visit turned into a three-year stay when he was offered a post as the first professor of Zoology at the Tokyo Imperial University

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

. He went on to recommend several fellow Americans as ''o-yatoi gaikokujin

The foreign employees in Meiji Japan, known in Japanese as ''O-yatoi Gaikokujin'' ( Kyūjitai: , Shinjitai: , "hired foreigners"), were hired by the Japanese government and municipalities for their specialized knowledge and skill to assist in the ...

'' (foreign advisors) to support the modernization of Japan in the Meiji Era

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization b ...

. To collect specimens, he established a marine biological laboratory at Enoshima

is a small offshore island, about in circumference, at the mouth of the Katase River which flows into the Sagami Bay of Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. Administratively, Enoshima is part of the mainland city of Fujisawa, and is linked to ...

in Kanagawa Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located in the Kantō region of Honshu. Kanagawa Prefecture is the second-most populous prefecture of Japan at 9,221,129 (1 April 2022) and third-densest at . Its geographic area of makes it fifth-smallest. Kana ...

.

While looking out of a window on a train between Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

and Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

, Morse discovered the Ōmori

is a district located a few kilometres south of Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan accessed by rail via the Keihin Tohoku line, or by road via Dai Ichi Keihin. Ōmorikaigan, the eastern area of Ōmori, can be reached via the Keikyu line.

Ōmori is one o ...

shell mound

A midden (also kitchen midden or shell heap) is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and ecofact ...

, the excavation of which opened the study in archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

and anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

in Japan and shed much light on the material culture of prehistoric Japan. He returned to Japan in 1882–3 to present a report of his findings to Tokyo Imperial University.

Morse had much interest in Japanese ceramics

, is one of the oldest Japanese crafts and Japanese art, art forms, dating back to the Neolithic period. Kilns have produced earthenware, pottery, stoneware, Ceramic glaze, glazed pottery, glazed stoneware, porcelain, and Blue and white porcel ...

, making a collection of over 5,000 pieces of Japanese pottery. On his 1882-3 visit to Japan he collected clay samples as well as finished ceramics. He devised the term "cord-marked" for the sherd

In archaeology, a sherd, or more precisely, potsherd, is commonly a historic or prehistoric fragment of pottery, although the term is occasionally used to refer to fragments of stone and glass vessels, as well.

Occasionally, a piece of broken p ...

s of Stone Age pottery, decorated by impressing cords into the wet clay. The Japanese translation, "Jōmon," now gives its name to the whole Jōmon period

The is the time in Japanese history, traditionally dated between 6,000–300 BCE, during which Japan was inhabited by a diverse hunter-gatherer and early agriculturalist population united through a common Jōmon culture, which reached a c ...

as well as Jōmon pottery

The is a type of ancient earthenware pottery which was made during the Jōmon period in Japan. The term "Jōmon" () means "rope-patterned" in Japanese, describing the patterns that are pressed into the clay.

Outline

Oldest pottery in Jap ...

. He brought back to Boston a collection amassed by government minister and amateur art collector Ōkuma Shigenobu

Marquess was a Japanese statesman and a prominent member of the Meiji oligarchy. He served as Prime Minister of the Empire of Japan in 1898 and from 1914 to 1916. Ōkuma was also an early advocate of Western science and culture in Japan, and ...

, who donated it to Morse in recognition of his services to Japan. These now form part of the "Morse Collection" of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

The Museum of Fine Arts (often abbreviated as MFA Boston or MFA) is an art museum in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the 20th-largest art museum in the world, measured by public gallery area. It contains 8,161 paintings and more than 450,000 works ...

. The catalogue is a monumental work, and still the only major work of its kind in English. His collection of daily artifacts of the Japanese people

The are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Japanese archipelago."人類学上は,旧石器時代あるいは縄文時代以来,現在の北海道〜沖縄諸島(南西諸島)に住んだ集団を祖先にもつ人々。" () Jap ...

is kept at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts

Salem ( ) is a historic coastal city in Essex County, Massachusetts, located on the North Shore of Greater Boston. Continuous settlement by Europeans began in 1626 with English colonists. Salem would become one of the most significant seaports tr ...

. The remainder of the collection was inherited by his granddaughter, Catharine Robb Whyte via her mother Edith Morse Robb and is housed at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Banff, Alberta, Canada.

He travelled several times to the Far East which inspired several books, with his own illustrations. '' Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings'' was published in 1885; ''On the Older Forms of Terra-cotta Roofing Tiles'' in 1892; ''Latrines of the East'' in 1893; ''Glimpses of China and Chinese Homes'' in 1903; and ''Japan Day by Day'' in 1917.

Massachusetts

After leaving Japan, Morse traveled to Southeast Asia and Europe. In subsequent years, he returned to Europe, and Japan in quest of pottery.

In 1886 Morse became president of the

After leaving Japan, Morse traveled to Southeast Asia and Europe. In subsequent years, he returned to Europe, and Japan in quest of pottery.

In 1886 Morse became president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is an American international non-profit organization with the stated goals of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific respons ...

. He became Keeper of Pottery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1890. He was also a director of the Peabody Academy of Science (now part of and succeeded by the Peabody Essex Museum

The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) in Salem, Massachusetts, US, is a successor to the East India Marine Society, established in 1799. It combines the collections of the former Peabody Museum of Salem (which acquired the Society's collection) and the ...

) in Salem from 1880 to 1914. In 1898, he was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun

The is a Japanese order, established in 1875 by Emperor Meiji. The Order was the first national decoration awarded by the Japanese government, created on 10 April 1875 by decree of the Council of State. The badge features rays of sunlight ...

(3rd class) by the Japanese government. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society in ...

in 1898. He became chairman of the Boston Museum in 1914, and chairman of the Peabody Museum in 1915. He was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasures

The is a Japanese order, established on 4 January 1888 by Emperor Meiji as the Order of Meiji. Originally awarded in eight classes (from 8th to 1st, in ascending order of importance), since 2003 it has been awarded in six classes, the lowest t ...

(2nd class) by the Japanese government in 1922.

Morse was a friend of astronomer Percival Lowell

Percival Lowell (; March 13, 1855 – November 12, 1916) was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled speculation that there were canals on Mars, and furthered theories of a ninth planet within the Solar System. ...

, who inspired interest in the planet Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

. Morse would occasionally journey to the Lowell Observatory

Lowell Observatory is an astronomical observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, United States. Lowell Observatory was established in 1894, placing it among the oldest observatories in the United States, and was designated a National Historic Landmark ...

in Flagstaff, Arizona

Flagstaff ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Coconino County, Arizona, Coconino County in northern Arizona, in the southwestern United States. In 2019, the city's estimated population was 75,038. Flagstaff's combined metropolitan area has ...

, during optimal viewing times to observe the planet. In 1906, Morse published ''Mars and Its Mystery'' in defense of Lowell's controversial speculations regarding the possibility of life on Mars.

He donated over 10,000 books from his personal collection to the Tokyo Imperial University. On learning that the library of the Tokyo Imperial University was reduced to ashes by the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake

The struck the Kantō Plain on the main Japanese island of Honshū at 11:58:44 JST (02:58:44 UTC) on Saturday, September 1, 1923. Varied accounts indicate the duration of the earthquake was between four and ten minutes. Extensive firestorms an ...

, in his will he ordered that his entire remaining collection of books be donated to Tokyo Imperial University.

Morse's last paper, on shell-mounds, was published in 1925. He died at his home in Salem, Massachusetts

Salem ( ) is a historic coastal city in Essex County, Massachusetts, located on the North Shore of Greater Boston. Continuous settlement by Europeans began in 1626 with English colonists. Salem would become one of the most significant seaports tr ...

in December of that year, of cerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as cerebral bleed, intraparenchymal bleed, and hemorrhagic stroke, or haemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into the tissues of the brain, into its ventricles, or into both. It is one kind of bleed ...

. He was buried at the Harmony Grove Cemetery.

Morse's Law

In 1872, Morse noticed that mammals and reptiles with reducedfingers

A finger is a limb of the body and a type of digit, an organ of manipulation and sensation found in the hands of most of the Tetrapods, so also with humans and other primates. Most land vertebrates have five fingers (Pentadactyly). Chambers 1 ...

lose them beginning from the sides: thumb

The thumb is the first digit of the hand, next to the index finger. When a person is standing in the medical anatomical position (where the palm is facing to the front), the thumb is the outermost digit. The Medical Latin English noun for thumb ...

the first and little finger

The little finger, or pinkie, also known as the baby finger, fifth digit, or pinky finger, is the most ulnar and smallest digit of the human hand, and next to the ring finger.

Etymology

The word "pinkie" is derived from the Dutch word ''pink ...

the second. Later researchers revealed that this is a general pattern in tetrapods (except Theropoda

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally ca ...

and Urodela

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All ten ...

): digits are reduced in the order I → V → II → III → IV, the reverse order of their appearance in embryogenesis. This trend is known as Morse's Law.

Published works

* 1875''First Book of Zoölogy''

New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1, 3, and 5 Bond Street

Second Edition, 1886

* 1885

''Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings.''

New York:

Harper & Brothers

Harper is an American publishing house, the flagship imprint of global publisher HarperCollins based in New York City.

History

J. & J. Harper (1817–1833)

James Harper and his brother John, printers by training, started their book publishin ...

OCLC 3050569

* 189

''On the Older Forms of Terra-cotta Roofing Tiles''

Bulletin of the Essex Institute 24: 1-72 * 189

''Latrines of the East''

The American Architect and Building News 39: 170-174 * 1901

''Catalogue of the Morse collection of Japanese pottery''

Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press. * 1902

''Glimpses of China and Chinese Homes.''

Boston:

Little, Brown

Little, Brown and Company is an American publishing company founded in 1837 by Charles Coffin Little and James Brown in Boston. For close to two centuries it has published fiction and nonfiction by American authors. Early lists featured Emily D ...

OCLC 1116550

* 1917. ''Japan Day by Day, 1877, 1878-79, 1882-83.'' Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Company

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (; HMH) is an American publisher of textbooks, instructional technology materials, assessments, reference works, and fiction and non-fiction for both young readers and adults. The company is based in the Boston Financ ...

OCLC 412843

See also

*American Association of Museums

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

* Takamine Hideo

was an administrator and educator in Meiji period Japan.

Early life

Takamine was born to a ''samurai'' family in Aizuwakamatsu domain (present day Fukushima Prefecture) in 1854. After completing his studies in the feudal domain's school, ''Ni ...

* Hiram M. Hiller, Jr.

Hiram Milliken Hiller Jr. (March 8, 1867 – August 8, 1921) was an American physician, medical missionary, explorer, and ethnographer. He traveled in Oceania and in South, Southeast, and East Asia, returning with archeological, cultural, zoolo ...

References

Further reading

* Benfey, Christopher (2003)''The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics, and the Opening of Old Japan,''

New York:

Random House

Random House is an American book publisher and the largest general-interest paperback publisher in the world. The company has several independently managed subsidiaries around the world. It is part of Penguin Random House, which is owned by Germ ...

. OCLC 50511058

* Rosenstone, Robert A. (1988)

''Mirror in the Shrine: American Encounters with Meiji Japan.''

Cambridge:

Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. After the retirem ...

. OCLC 17108604

* Wayman, Dorothy Godfrey. (1942) ''Edward Sylvester Morse: A Biography.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press

OCLC 757515

* 2018. ''From Morse to Whyte: A Dynastic Bequest of Japanese Treasures''. Catalogue published by the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Banff, AB. Canada

External links

* Museum of Fine Arts, Boston"Japanese Ceramics from the Collection of Edward Sylvester Morse."

* * * Whyte Museum {{DEFAULTSORT:Morse, Edward S. American anthropologists American expatriates in Japan American curators American zoologists Foreign advisors to the government in Meiji-period Japan Foreign educators in Japan Museum of Fine Arts, Boston People from Portland, Maine 1838 births 1925 deaths Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Treasure University of Tokyo faculty Burials at Harmony Grove Cemetery Members of the American Antiquarian Society