Edward Hawke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

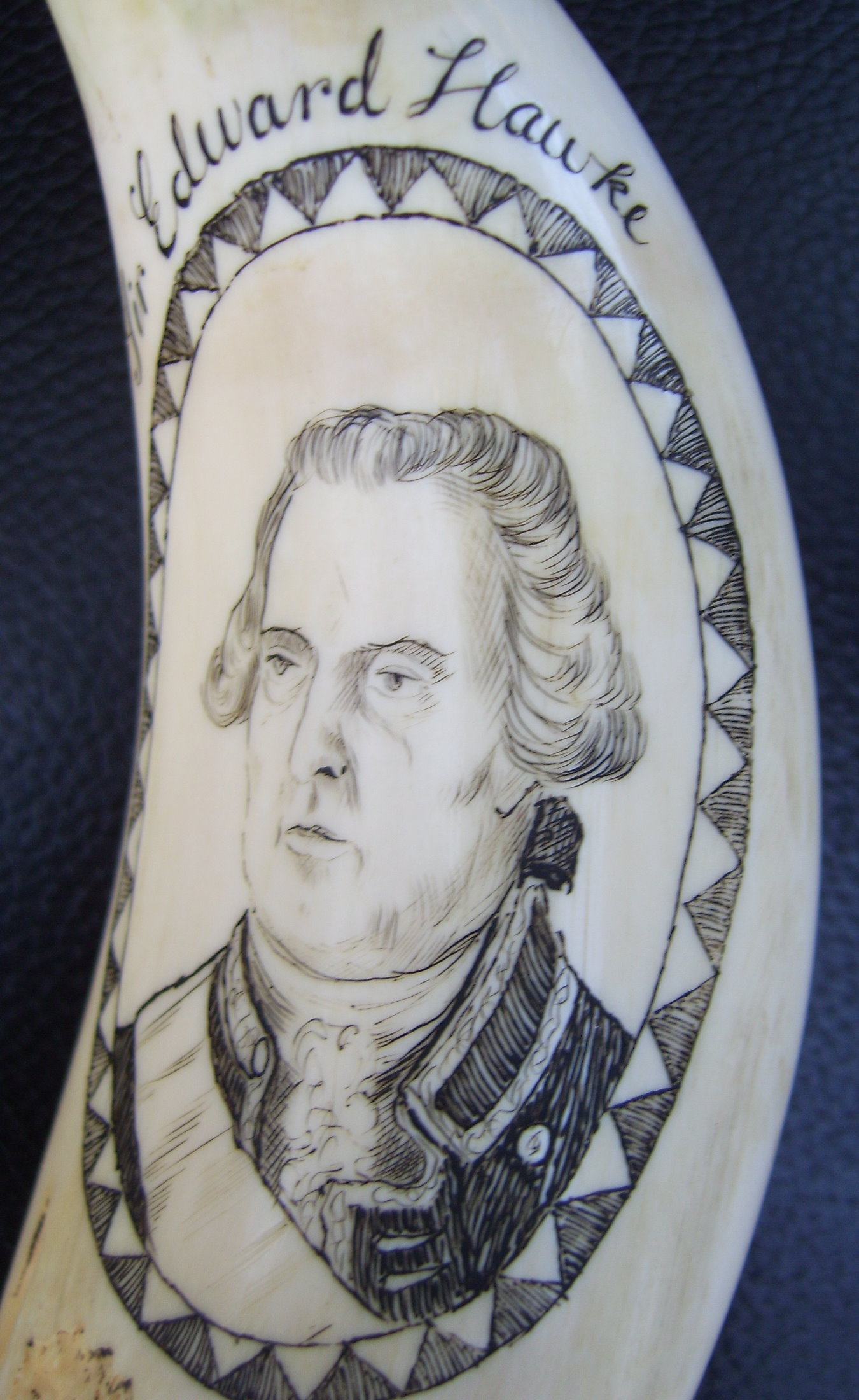

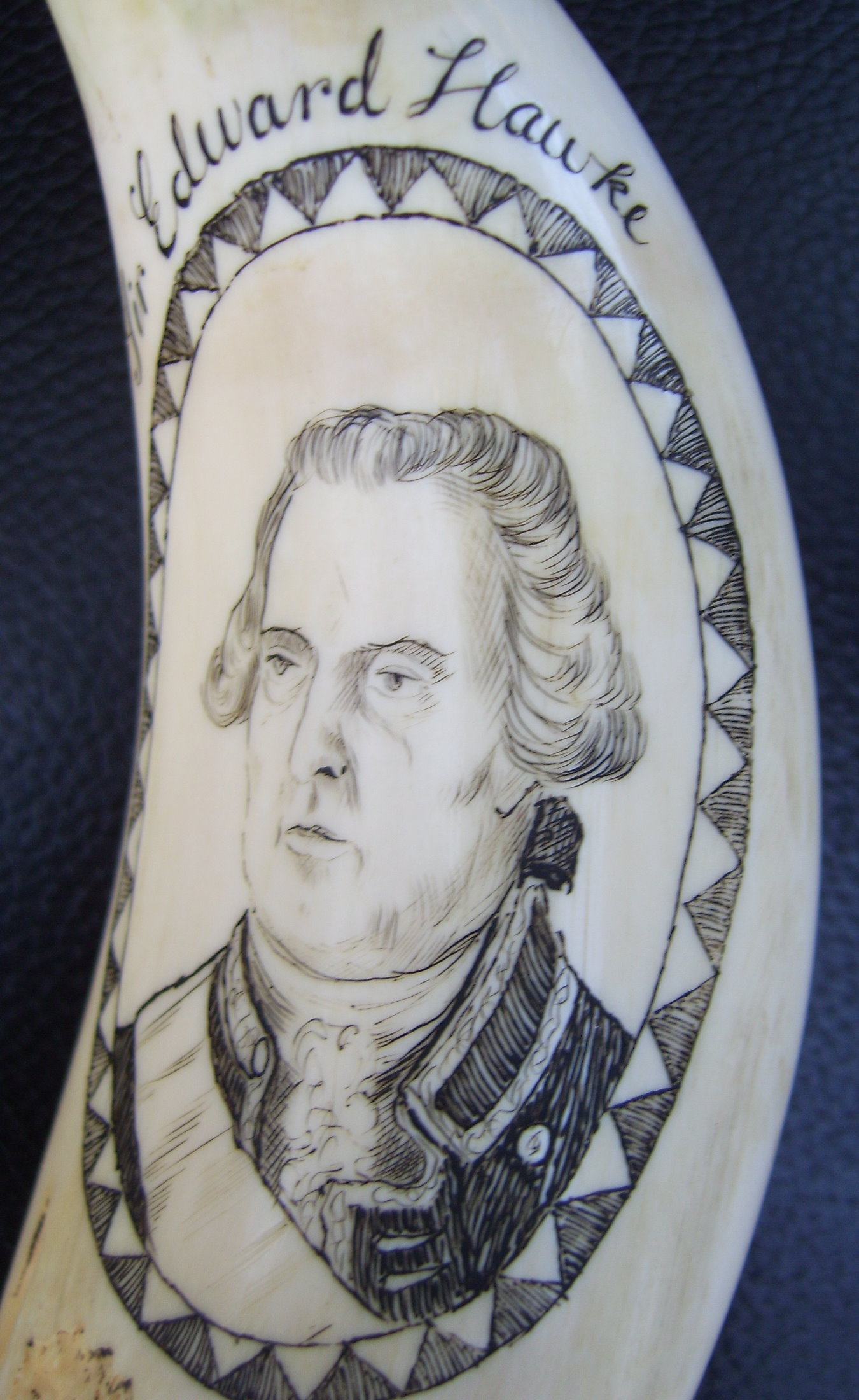

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a

Hawke became commanding officer of the

Hawke became commanding officer of the

The British had received word that there was now an incoming convoy arriving from the West Indies. Hawke took his fleet and lay in wait for the arrival of the French. In October 1747, Hawke captured six ships of a French squadron in the

The British had received word that there was now an incoming convoy arriving from the West Indies. Hawke took his fleet and lay in wait for the arrival of the French. In October 1747, Hawke captured six ships of a French squadron in the

For Hawke, however, the arrival of peace brought a sudden end to his opportunities for active service. In December 1747, he was elected as a

For Hawke, however, the arrival of peace brought a sudden end to his opportunities for active service. In December 1747, he was elected as a

Hawke blockaded

Hawke blockaded

Although Hawke's victory at Quiberon Bay ended any immediate hope of a major invasion of

Although Hawke's victory at Quiberon Bay ended any immediate hope of a major invasion of

In an effort to further undermine the French, Pitt had conceived the idea of seizing the island of

In an effort to further undermine the French, Pitt had conceived the idea of seizing the island of

Hawke then retired from active duty, and became Rear-Admiral of Great Britain on 4 January 1763 and

Hawke then retired from active duty, and became Rear-Admiral of Great Britain on 4 January 1763 and

His memorial, carved by John Francis Moore and depicting the Battle of Quiberon Bay, is in St. Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham

In the iconic 1883 novel

His memorial, carved by John Francis Moore and depicting the Battle of Quiberon Bay, is in St. Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham

In the iconic 1883 novel

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

officer. As captain of the third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the thi ...

, he took part in the Battle of Toulon in February 1744 during the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George ...

. He also captured six ships of a French squadron in the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

in the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre

The second battle of Cape Finisterre was a naval encounter fought during the War of the Austrian Succession on 25 October 1747 (N.S.). A British fleet of fourteen ships of the line commanded by Rear-Admiral Edward Hawke intercepted a French ...

in October 1747.

Hawke went on to achieve a victory over a French fleet at the Battle of Quiberon Bay

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as ''Bataille des Cardinaux'' in French) was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off the coast ...

in November 1759 during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, preventing a French invasion of Britain. He developed the concept of a Western Squadron

The Western Squadron was a squadron or formation of the Royal Navy based at Plymouth Dockyard. It operated in waters of the English Channel, the Western Approaches, and the North Atlantic. It defended British trade sea lanes from 1650 to 1814 and ...

, keeping an almost continuous blockade of the French coast throughout the war.

Hawke also sat in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

from 1747 to 1776 and served as First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

for five years between 1766 and 1771. In this post, he was successful in bringing the navy's spending under control and also oversaw the mobilisation of the navy during the Falklands Crisis in 1770.

Origins

He was the only son of Edward Hawke, abarrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and givin ...

of Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of the four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. (The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn.) Lincol ...

, by his wife Elizabeth Bladen, a daughter of Nathaniel Bladen of Hemsworth in Yorkshire, and widow of Col. Ruthven. Hawke benefited from the patronage of his maternal uncle Colonel Martin Bladen

Colonel Martin Bladen (1680–1746) was a British politician who sat in the Irish House of Commons from 1713 to 1727 and in the British House of Commons from 1715 to 1746. He was a Commissioner of the Board of Trade and Plantations, a Privy Counc ...

, a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

.

Early life

Hawke joined the navy as a volunteer in thesixth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a sixth-rate was the designation for small warships mounting between 20 and 28 carriage-mounted guns on a single deck, sometimes with smaller guns on the upper works a ...

on the North American Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956. The North American Station was separate from the Jamaica Station until 1830 when the ...

in February 1720.Heathcote, p. 107. Promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

on 2 June 1725, he transferred to the fifth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a fifth rate was the second-smallest class of warships in a hierarchical system of six " ratings" based on size and firepower.

Rating

The rating system in the Royal ...

on the West Coast of Africa later that month, to the fourth-rate

In 1603 all English warships with a compliment of fewer than 160 men were known as 'small ships'. In 1625/26 to establish pay rates for officers a six tier naval ship rating system was introduced.Winfield 2009 These small ships were divided i ...

in the Channel Squadron in April 1729 and to the fourth-rate in November 1729. After that he moved to the fourth-rate HMS ''Edinburgh'' in the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

in May 1731, to the sixth-rate in January 1732 and to the fourth-rate , flagship of Commodore Sir Chaloner Ogle, Commander-in-Chief of the Jamaica Station, in December 1732.

After this, Hawke's career accelerated: promoted to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

on 13 April 1733, he became commanding officer of the sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

later that month and promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 20 March 1734, he became commanding officer of the sixth-rate later that month. The following year he went on half-pay Half-pay (h.p.) was a term used in the British Army and Royal Navy of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries to refer to the pay or allowance an officer received when in retirement or not in actual service.

Past usage United Kingdom

In the En ...

and did not go to sea again until July 1739 when he was recalled to become commanding officer of HMS ''Portland'' on the North American Station and was sent to cruise in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

with orders to escort British merchant ships. He did this successfully, although it meant his ship did not take part in the British attack on Porto Bello in November 1739 during the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

.

Battle of Toulon

Hawke became commanding officer of the

Hawke became commanding officer of the third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the thi ...

in June 1743: he did not see action until the Battle of Toulon in February 1744 during the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George ...

. The fight at Toulon was extremely confused, although Hawke had emerged from it with a degree of credit. While not a defeat for the British, they had failed to take an opportunity to comprehensively defeat the Franco-Spanish fleet when a number of British ships had not engaged the enemy, leading to a mass court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

. Hawke's ship managed to capture the only prize of the battle, the Spanish ship ''Poder'', although it was subsequently destroyed by the French. He was then given command of the second-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a second-rate was a ship of the line which by the start of the 18th century mounted 90 to 98 guns on three gun decks; earlier 17th-century second rates had fewer gun ...

in August 1745.

Battle of Cape Finisterre

Despite having distinguished himself at Toulon, Hawke had few opportunities over the next three years. However, he was promoted torear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

on 15 July 1747 and appointed Second-in-Command of the Western Squadron

The Western Squadron was a squadron or formation of the Royal Navy based at Plymouth Dockyard. It operated in waters of the English Channel, the Western Approaches, and the North Atlantic. It defended British trade sea lanes from 1650 to 1814 and ...

, with his flag in the fourth-rate in August 1747. He went on to replace Admiral Peter Warren as the Commander-in-Chief, English Channel in charge of the Western Squadron

The Western Squadron was a squadron or formation of the Royal Navy based at Plymouth Dockyard. It operated in waters of the English Channel, the Western Approaches, and the North Atlantic. It defended British trade sea lanes from 1650 to 1814 and ...

, with his flag in the third-rate , in October 1747.Heathcote, p. 108. Hawke then put a great deal of effort into improving the performance of his crews and instilling in them a sense of pride and patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, language relating to one's own homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political or histor ...

. The Western Squadron had been established to keep a watch on the French Channel ports. Under a previous commander, Lord Anson

Admiral of the Fleet George Anson, 1st Baron Anson, (23 April 1697 – 6 June 1762) was a Royal Navy officer. Anson served as a junior officer during the War of the Spanish Succession and then saw active service against Spain at the Battl ...

, it had successfully contained the French coast and in May 1747 won the First Battle of Cape Finisterre

The First Battle of Cape Finisterre (14 May 1747in the Julian calendar then in use in Britain this was 3 May 1747) was waged during the War of the Austrian Succession. It refers to the attack by 14 British ships of the line under Admiral George ...

when it attacked a large convoy leaving harbour.

The British had received word that there was now an incoming convoy arriving from the West Indies. Hawke took his fleet and lay in wait for the arrival of the French. In October 1747, Hawke captured six ships of a French squadron in the

The British had received word that there was now an incoming convoy arriving from the West Indies. Hawke took his fleet and lay in wait for the arrival of the French. In October 1747, Hawke captured six ships of a French squadron in the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

in the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre

The second battle of Cape Finisterre was a naval encounter fought during the War of the Austrian Succession on 25 October 1747 (N.S.). A British fleet of fourteen ships of the line commanded by Rear-Admiral Edward Hawke intercepted a French ...

. The consequence of this, along with Anson's earlier victory, was to give the British almost total control in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

during the final months of the war. It proved ruinous to the French economy, helping the British to secure an acceptable peace at the negotiations for the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.

Peace

For Hawke, however, the arrival of peace brought a sudden end to his opportunities for active service. In December 1747, he was elected as a

For Hawke, however, the arrival of peace brought a sudden end to his opportunities for active service. In December 1747, he was elected as a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for the naval town of Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

, which he was to represent for the next thirty years. He was not on good terms with the new First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

, Lord Anson

Admiral of the Fleet George Anson, 1st Baron Anson, (23 April 1697 – 6 June 1762) was a Royal Navy officer. Anson served as a junior officer during the War of the Spanish Succession and then saw active service against Spain at the Battl ...

, although they shared similar views on how any future naval war against France should be waged. In spite of their personal disagreements, Anson had a deep respect for Hawke as an admiral, and pushed unsuccessfully for him to be given a place on the Admiralty board

The Admiralty Board is the body established under the Defence Council of the United Kingdom for the administration of the Naval Service of the United Kingdom. It meets formally only once a year, and the day-to-day running of the Royal Navy is ...

. Promoted to vice admiral on 26 May 1748, he became Port Admiral at Portsmouth serving in that post for three years. He was installed as a Knight Companion of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) a ...

(KB) on 26 June 1749 and was recalled as Port Admiral at Portsmouth in 1755.

Seven Years' War

As it began to seem more likely that war would break out with France, Hawke was ordered to hoist his flag in the first-rate HMS ''St George'' and to reactivate the Western Squadron in Spring 1755. This was followed by a command to cruise off the coast of France intercepting ships bound for French harbours. He did this very successfully, and British ships captured more than 300 merchant ships during the period. This in turn further worsened relations between Britain and France, bringing them to the brink of declaring war. France would continue to demand the return of the captured merchant ships throughout the coming war. By early 1756, after repeated clashes in North America, and deteriorating relations in Europe, the two sides were formally at war.Fall of Menorca

Hawke was sent to replace AdmiralJohn Byng

Admiral John Byng (baptised 29 October 1704 – 14 March 1757) was a British Royal Navy officer who was court-martialled and executed by firing squad. After joining the navy at the age of thirteen, he participated at the Battle of Cape Pass ...

as commander in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

, with orders to hoist his flag in the second-rate HMS ''Ramillies'', in June 1756. Byng had been unable to relieve Menorca (historically called "Minorca" by the British) following the Battle of Minorca

The island of Menorca in the Mediterranean Sea has been invaded on numerous occasions. The first recorded invasion occurred in 252 BC, when the Carthaginians arrived. The name of the island's chief city, Mahón (now Maó), appears to derive from t ...

and he was sent back to Britain where he was tried and executed. Almost as soon as Menorca had fallen in June 1756, the French fleet had withdrawn to Toulon in case they were attacked by Hawke. Once he arrived off Menorca, Hawke found that the island had surrendered and there was little he could do to reverse this. He decided not to land the troops he had brought with him from Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

. Hawke then spent three months cruising off Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its cap ...

and Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

before returning home where he gave evidence against Byng. Hawke was subsequently criticised by some supporters of Byng, for not having blockaded either Menorca or Toulon. He was promoted to full admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

on 24 February 1757.

Descent on Rochefort

Hawke blockaded

Hawke blockaded Rochefort

Rochefort () may refer to:

Places France

* Rochefort, Charente-Maritime, in the Charente-Maritime department

** Arsenal de Rochefort, a former naval base and dockyard

* Rochefort, Savoie in the Savoie department

* Rochefort-du-Gard, in the Ga ...

in 1757 and later in the year he was selected to command a naval escort that would land a large force on the coast of France. The expedition arrived off the coast of Rochefort in September. After storming the offshore island of Île-d'Aix, the army commander Sir John Mordaunt hesitated before proceeding with the landing on the mainland. Despite a report by Colonel James Wolfe

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the French at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec. ...

that they would be able to capture Rochefort, Mordaunt was reluctant to attack. Hawke then offered an ultimatum – either the Generals attacked immediately or he would sail for home. His fleet was needed to protect an inbound convoy from the West Indies, and could not afford to sit indefinitely off Rochefort. Mourdaunt hastily agreed, and the expedition returned to Britain without having made any serious attempt on the town. The failure of the expedition led to an inquiry

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the ...

which recommended the court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

of Mordaunt, which commenced on 14 December 1757 and at which he was acquitted.

In 1758 Hawke directed the blockade of Brest for six months. In 1758 he was involved in a major altercation with his superiors at the Admiralty which saw him strike his flag and return to port over a misunderstanding at which he took offence. Although he later apologised, he was severely reprimanded. In Hawke's absence the Channel Fleet was placed under the direct command of Lord Anson.Heathcote, p. 109.

Battle of Quiberon Bay

In May 1759 Hawke was restored to the command of theWestern Squadron

The Western Squadron was a squadron or formation of the Royal Navy based at Plymouth Dockyard. It operated in waters of the English Channel, the Western Approaches, and the North Atlantic. It defended British trade sea lanes from 1650 to 1814 and ...

. Meanwhile, the Duc de Choiseul {{Unreferenced, date=April 2019

Choiseul is an illustrious noble family from Champagne, France, descendants of the comtes of Langres. The family's head was Renaud III de Choiseul, comte de Langres and sire de Choiseul, who in 1182 married Alix ...

was planning a French invasion of Britain. A French army was assembled in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

, with plans to combine the separate French fleets so they could seize control of the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

and allow the invasion force to cross and capture London. When Hawke's force was driven off station by a storm, the French fleet under Hubert de Brienne, Comte de Conflans, took advantage and left port. During a gale on 20 November 1759 Hawke took the risky decision to follow French warships in to an area of shoals and rocky islands. The British, unlike the French, had no maps or knowledge of the area, and the French admiral fully expected the British ships to wreck themselves in the dangerous waters. Hawke ordered the master of his ship to follow the French admiral in to these waters. The master of the ''Royal George'', Hawke's flagship, is said to have remonstrated as to the danger of doing so, further compounded by a lee-shore. To this Hawke gave his famous reply "You have done your duty Sir, now lay me alongside the Soleil Royal". He won a sufficient victory in the Battle of Quiberon Bay

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as ''Bataille des Cardinaux'' in French) was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off the coast ...

, that when combined with admiral Edward Boscawen

Admiral of the Blue Edward Boscawen, PC (19 August 171110 January 1761) was a British admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament for the borough of Truro, Cornwall, England. He is known principally for his various naval commands during ...

's victory at the Battle of Lagos

The naval Battle of Lagos took place between a British fleet commanded by Sir Edward Boscawen and a French fleet under Jean-François de La Clue-Sabran over two days in 1759 during the Seven Years' War. They fought south west of the Gulf of C ...

, the French invasion threat was removed. Although he had effectively put the French channel fleet out of action for the remainder of the war, Hawke was disappointed he had not secured a more comprehensive victory, asserting that had he had two more hours of daylight the whole enemy fleet would have been taken.

Blockade of Brest

Although Hawke's victory at Quiberon Bay ended any immediate hope of a major invasion of

Although Hawke's victory at Quiberon Bay ended any immediate hope of a major invasion of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

, the French continued to entertain hopes of a future invasion for the remainder of the war, which drove the British to keep a tight blockade on the French coast. This continued to starve French ports of commerce, further weakening France's economy. After a spell in England, Hawke returned to take command of the blockading fleet off Brest. The British were now effectively mounting a blockade of the French coast from Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

to Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

. Hawke attempted to destroy some of the remaining French warships, which he had trapped in the Vilaine Estuary. He sent in fire ship

A fire ship or fireship, used in the days of wooden rowed or sailing ships, was a ship filled with combustibles, or gunpowder deliberately set on fire and steered (or, when possible, allowed to drift) into an enemy fleet, in order to destroy sh ...

s, but these failed to accomplish the task. Hawke developed a plan for landing on the coast, seizing a peninsula, and attacking the ships from land. However, he was forced to abandon this when orders reached him from Pitt for a much larger expedition.

Capture of Belle Île

In an effort to further undermine the French, Pitt had conceived the idea of seizing the island of

In an effort to further undermine the French, Pitt had conceived the idea of seizing the island of Belle Île

Belle-Île, Belle-Île-en-Mer, or Belle Isle ( br, Ar Gerveur, ; br, label=Old Breton, Guedel) is a French island off the coast of Brittany in the ''département'' of Morbihan, and the largest of Brittany's islands. It is from the Quiberon peni ...

, off the coast of Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

and asked the navy to prepare for an expedition to take it. Hawke made his opposition clear in a letter to Anson, which was subsequently widely circulated. Pitt was extremely annoyed by this, considering that Hawke had overstepped his authority. Nonetheless, Pitt pressed ahead with the expedition against Belle Île. An initial assault in April 1761 was repulsed with heavy loss but, reinforced, the British successfully captured the island in June. Although the capture of the island provided another victory for Pitt, and lowered the morale of the French public by showing that the British could now occupy parts of Metropolitan France

Metropolitan France (french: France métropolitaine or ''la Métropole''), also known as European France (french: Territoire européen de la France) is the area of France which is geographically in Europe. This collective name for the European ...

– Hawke's criticisms of its strategic usefulness were borne out. It was not a useful staging point for further raids on the coast and the French were not especially concerned about its loss, telling Britain during subsequent peace negotiations that they would offer nothing in exchange for it and Britain could keep it if they wished.

First Lord of the Admiralty

Hawke then retired from active duty, and became Rear-Admiral of Great Britain on 4 January 1763 and

Hawke then retired from active duty, and became Rear-Admiral of Great Britain on 4 January 1763 and Vice-Admiral of Great Britain

The Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom is an honorary office generally held by a senior Royal Navy admiral. The title holder is the official deputy to the Lord High Admiral, an honorary (although once operational) office which was vested in th ...

on 5 November 1765. He was made First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

in the Chatham Ministry in December 1766 and promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on 15 January 1768. His appointment drew on his expertise on naval matters, as he did little to enhance the government politically. During his time as First Lord, Hawke was successful in bringing the navy's spending under control. He also oversaw the mobilisation of the navy during the Falklands Crisis in 1770 and was then succeeded as First Lord by Lord Sandwich

Earl of Sandwich is a noble title in the Peerage of England, held since its creation by the House of Montagu. It is nominally associated with Sandwich, Kent. It was created in 1660 for the prominent naval commander Admiral Sir Edward Montagu. ...

in January 1771.

Hawke was influential in the decision to give Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

command of his first expedition that left in 1768. When at a meeting in the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

it was suggested that a civilian should lead the expedition Hawke is supposed to have remarked that, he would sooner have his right hand cut off than allow this to happen. Cook named a series of prominent places that he came across in the 'New World' after Hawke as a sign of his gratitude.

Hawke was created Baron Hawke "of Towton" (in which Yorkshire parish was situated his residence of Scarthingwell Hall, inherited by his wife) on 20 May 1776. Towards the end of his life he had his country house built in Sunbury-on-Thames

Sunbury-on-Thames (or commonly Sunbury) is a suburban town on the north bank of the River Thames in the Borough of Spelthorne, Surrey, centred southwest of central London. Historically part of the county of Middlesex, in 1965 Sunbury and other ...

and lived alternately there and at a rented home in North Stoneham

North Stoneham is a settlement and ecclesiastical parish located in between Eastleigh and Southampton in south Hampshire, England. It was formerly an ancient estate and manor. Until the nineteenth century, it was a rural community comprising a nu ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

. He died at his house in Sunbury-on-Thames on 17 October 1781 and was buried at St. Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham.Heathcote, p. 110.

Cultural references

His memorial, carved by John Francis Moore and depicting the Battle of Quiberon Bay, is in St. Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham

In the iconic 1883 novel

His memorial, carved by John Francis Moore and depicting the Battle of Quiberon Bay, is in St. Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham

In the iconic 1883 novel Treasure Island

''Treasure Island'' (originally titled ''The Sea Cook: A Story for Boys''Hammond, J. R. 1984. "Treasure Island." In ''A Robert Louis Stevenson Companion'', Palgrave Macmillan Literary Companions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. .) is an adventure no ...

, Robert Louis Stevenson has Long John Silver

Long John Silver is a Character (arts), fictional character and the main antagonist in the novel ''Treasure Island'' (1883) by Robert Louis Stevenson. The most colourful and complex character in the book, he continues to appear in popular cult ...

claim that he "Served in the Royal Navy and lost his leg under "the immortal Hawke"."

Places named after Hawke include:

;Australia

* Cape Hawke

Cape Hawke () is a coastal headland in Australia on the New South Wales coast, just south of Forster/Tuncurry and within the Booti Booti National Park.

The cape was named by Captain Cook when he passed it on his ''Endeavour'' voyage on 12 May 1 ...

in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

.

;New Zealand

* Hawke Bay and subsequently Hawke's Bay

Hawke's Bay ( mi, Te Matau-a-Māui) is a local government region on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island. The region's name derives from Hawke Bay, which was named by Captain James Cook in honour of Admiral Edward Hawke. The region i ...

Region in the North Island

The North Island, also officially named Te Ika-a-Māui, is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but much less populous South Island by the Cook Strait. The island's area is , making it the world's 14th-larges ...

.

;Canada

* Hawke's Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador

Hawke's Bay is a town at the mouth of Torrent River southeast of Point Riche in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

History

The town was named after Edward Hawke by James Cook in 1766. This was to commemorate Hawke's victor ...

.

* Port Hawkesbury, Nova Scotia

Port Hawkesbury (Scottish Gaelic: ''Baile a' Chlamhain'') is a municipality in southern Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. While within the historical county of Inverness, it is not part of the Municipality of Inverness County.

History ...

.

;Royal Navy ships named in Hawke's honour

* The 74-gun launched in 1820.

* built in 1891.

Marriage and issue

In 1737 he married Catherine Brooke, the only the daughter and sole heiress of Walter Brooke (1695-1722) of Burton Hall,Gateforth

Gateforth is a small village and civil parish located in North Yorkshire, England. The village is south west of the town of Selby and south of the village of Hambleton, where a shop a hotel and one pub are located. Gateforth is approximately ...

near Hull and of Gateforth Hall in Yorkshire, by his wife Catherine Hammond (d.1721) daughter and heiress of William Hammond of Scarthingwell Hall, in the parish of Towton, Yorkshire.History of Parliament biog states Catherine Hammond as "a grand-daughter and co-heiress of William Hammond of Scarthingwell Hall" Hawke made his home at Scarthingwell Hall and took for his barony the territorial designation "of Towton" from the parish in which it was situated. By his wife he had three sons and one daughter, who survived, and three children who died in infancy.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hawke, Edward Hawke, 1st Baron 1705 births 1781 deaths Peers of Great Britain created by George III British MPs 1747–1754 British MPs 1754–1761 British MPs 1761–1768 British MPs 1768–1774 British MPs 1774–1780 Knights Companion of the Order of the Bath Lords of the Admiralty Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain Royal Navy admirals of the fleet Royal Navy personnel of the Seven Years' War Royal Navy personnel of the War of the Austrian SuccessionEdward 1

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

Military personnel from London