Edward Carpenter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English

E M Forster’s gay fiction

The

, Philip Taylor 1988 and served as curate to Maurice at the parish of St Edward's, Cambridge. In 1871 Carpenter was invited to become tutor to the royal princes George Frederick (later King George V) and his elder brother,

Carpenter was voluntarily released from the Anglican ministry and left the church in 1874 and moved to

Carpenter was voluntarily released from the Anglican ministry and left the church in 1874 and moved to

utopian socialist

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

, poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or writte ...

, philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, anthologist

In book publishing, an anthology is a collection of literary works chosen by the compiler; it may be a collection of plays, poems, short stories, songs or excerpts by different authors.

In genre fiction, the term ''anthology'' typically catego ...

, an early activist for gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , 3 ...

Warren Allen Smith

Warren Allen Smith (October 27, 1921 – January 9, 2017) was an American writer, humanist and gay rights activist. A World War II veteran and an outspoken atheist, he dubbed himself as "the atheist in a foxhole".

Biography

From 1942 to 1946, ...

: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Humanists, Freethinkers, Naturalists, Rationalists, and Non-Theists'', Barricade Books, New York, 2000, p. 186; . and prison reform whilst advocating vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetarianism m ...

ism and taking a stance against vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for Animal testi ...

. As a philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

he was particularly known for his publication of ''Civilisation: Its Cause and Cure''. Here he described civilisation

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of State (polity), a state, social stratification, urban area, urbanization, and Symbol, symbolic systems of communication beyond natural language, natur ...

as a form of disease through which human societies pass.

An early advocate of sexual liberation, he had an influence on both D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

and Sri Aurobindo, and inspired E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author, best known for his novels, particularly ''A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910), and ''A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous short stori ...

's novel ''Maurice''.Symondson, Kate (25 May 2016E M Forster’s gay fiction

The

British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

website. Retrieved 18 July 2020

Early life

Born at 45 Brunswick Square,Hove

Hove is a seaside resort and one of the two main parts of the city of Brighton and Hove, along with Brighton in East Sussex, England. Originally a "small but ancient fishing village" surrounded by open farmland, it grew rapidly in the 19th c ...

in Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

, Carpenter was educated at nearby Brighton College

Brighton College is an independent, co-educational boarding and day school for boys and girls aged 3 to 18 in Brighton, England. The school has three sites: Brighton College (the senior school, ages 11 to 18); Brighton College Preparatory Sc ...

, where his father Charles Carpenter was a governor. His brothers Charles, George and Alfred also went to school there. Edward's grandfather was Vice-Admiral James Carpenter (d 1845). When he was ten, Carpenter displayed a flair for the piano.

His academic ability became evident relatively late in his youth, but was sufficient to earn him a place at Trinity Hall, Cambridge

Trinity Hall (formally The College or Hall of the Holy Trinity in the University of Cambridge) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

It is the fifth-oldest surviving college of the university, having been founded in 1350 by ...

.Rowbotham 2009. At Trinity Hall, Carpenter came under the influence of Christian Socialist

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe cap ...

theologian F. D. Maurice

John Frederick Denison Maurice (1805–1872), known as F. D. Maurice, was an English Anglican theologian, a prolific author, and one of the founders of Christian socialism. Since the Second World War, interest in Maurice has expanded."Fre ...

.Birch, Dinah, ''The Oxford Companion to English Literature''. Oxford, Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 2009. (p. 197). Whilst there he also began to explore his feelings for men. One of the most notable examples of this is his close friendship with Edward Anthony Beck

Edward Anthony Beck (21 March 1848 - 12 April 1916) was a British academic in the last third of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th.

Beck was educated at Bishop's Stortford College and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was to spe ...

(later Master of Trinity Hall), which, according to Carpenter, had "a touch of romance". Beck eventually ended their friendship, causing Carpenter great emotional heartache. Carpenter graduated as 10th Wrangler in 1868. After university, he was ordained as curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy w ...

of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, "as a convention rather than out of deep Conviction",Philip Taylor's Biography of Carpenter, Philip Taylor 1988 and served as curate to Maurice at the parish of St Edward's, Cambridge. In 1871 Carpenter was invited to become tutor to the royal princes George Frederick (later King George V) and his elder brother,

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (Albert Victor Christian Edward; 8 January 1864 – 14 January 1892) was the eldest child of the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra) and grandson of the re ...

, but declined the position. His lifelong friend and fellow Cambridge student John Neale Dalton took the position. Carpenter continued to visit Dalton while he was tutor. They were given photographs of the pair, taken by the princes.

In the following years he experienced an increasing sense of dissatisfaction with his life in the church and university, and became weary of what he saw as the hypocrisy of Victorian society. He found great solace in reading poetry, later remarking that his discovery of the work of Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

caused "a profound change" in him. Five or six years later he visited Whitman in Camden, New Jersey

Camden is a city in and the county seat of Camden County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Camden is part of the Delaware Valley metropolitan area and is located directly across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At the 2020 ...

, in 1877.

Move to the North of England

Carpenter was voluntarily released from the Anglican ministry and left the church in 1874 and moved to

Carpenter was voluntarily released from the Anglican ministry and left the church in 1874 and moved to Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

, becoming a lecturer

Lecturer is an List of academic ranks, academic rank within many universities, though the meaning of the term varies somewhat from country to country. It generally denotes an academic expert who is hired to teach on a full- or part-time basis. T ...

as part of University Extension Movement, which was formed by academics who wished to widen access to education in deprived communities. He lectured in astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, the lives of ancient Greek women and music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

and had hoped to lecture to the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

es, but found his lectures were mostly attended by middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

people, many of whom showed little active interest in the subjects he taught. Disillusioned, he moved to Chesterfield

Chesterfield may refer to:

Places Canada

* Rural Municipality of Chesterfield No. 261, Saskatchewan

* Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut United Kingdom

* Chesterfield, Derbyshire, a market town in England

** Chesterfield (UK Parliament constitue ...

, but finding that town dull, moved to nearby Sheffield

Sheffield is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is Historic counties o ...

a year later. Here he came into contact with manual workers, and he began to write poetry. His sexual preferences were for working men: "the grimy and oil-besmeared figure of a stoker" or "the thick-thighed hot coarse-fleshed young bricklayer with a strap around his waist".

When his father Charles Carpenter died in 1882, Edward inherited the sum of £6,000 (). This enabled Carpenter to quit his lectureship to seek the simpler life, first on a small holding

A smallholding or smallholder is a small farm operating under a small-scale agriculture model. Definitions vary widely for what constitutes a smallholder or small-scale farm, including factors such as size, food production technique or technology ...

at Totley near Sheffield with Albert Ferneyhough, a scythe-maker, and his family in 1880; Albert and Edward became lovers and in 1883 moved to Millthorpe, Derbyshire together with Albert's family, where Carpenter built a large new house with outbuildings in 1883 constructed of local gritstone with a slate roof, in the style of the seventeenth century. There they had a small market garden and made and sold leather sandals, based on the design of sandals sent to him from India by Harold Cox

Harold Cox (1859 – 1 May 1936) was a Liberal MP for Preston from 1906 to 1910.

Early life

The son of Homersham Cox, a County Court judge, Cox was educated at Tonbridge School in Kent and was scholar and later fellow at Jesus College, Cam ...

on Carpenter's request.

Carpenter popularised the phrase the "Simple Life" in his essay ''Simplification of Life'' in his ''England's Ideal'' (1887). Sheffield architect Raymond Unwin

Sir Raymond Unwin (2 November 1863 – 29 June 1940) was a prominent and influential English engineer, architect and town planner, with an emphasis on improvements in working class housing.

Early years

Raymond Unwin was born in Rotherham, Yorks ...

was a frequent visitor to Millthorpe and the simple revival of vernacular English architecture at Millthorpe and Carpenter's 'simple life' there were powerful influences on Unwin's later Garden City architecture and ideals, suggesting as they did a coherent but radical new lifestyle.

In Sheffield, Carpenter became increasingly radical. Influenced by a disciple of Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

''

On his return from India in 1891, he met George Merrill, a working-class man also from Sheffield, 22 years his junior, and after the Ferneyhoughs left Millthorpe in 1893 Merrill became Carpenter's companion. The two remained partners for the rest of their lives, cohabiting from 1898. Merrill, the son of an engine driver, had been raised in the slums of Sheffield and had little formal education.

Carpenter remarked in his work ''The Intermediate Sex'':

On his return from India in 1891, he met George Merrill, a working-class man also from Sheffield, 22 years his junior, and after the Ferneyhoughs left Millthorpe in 1893 Merrill became Carpenter's companion. The two remained partners for the rest of their lives, cohabiting from 1898. Merrill, the son of an engine driver, had been raised in the slums of Sheffield and had little formal education.

Carpenter remarked in his work ''The Intermediate Sex'':

Carpenter included among his friends the scholar, author, naturalist, and founder of the

Carpenter included among his friends the scholar, author, naturalist, and founder of the

Love, Sex, Death & Words: Surprising Tales From a Year in Literature

', p. 160. London: Icon Books. Retrieved 11 August 2020 (Google Books) The relationship between Carpenter and Merrill was an inspiration for the relationship between Maurice Hall and Alec Scudder, the gamekeeper in ''Maurice''. The author

In 1902 Carpenter's

In 1902 Carpenter's

at www.brightonourstory.co.uk and the two lived at 23 Mountside Rd. On Carpenter's 80th birthday he was presented an album signed by every member of the then

at www.adam-matthew-publications.co.uk Carpenter was a friend of

Carpenter was a friend of

''The Vegetarian Movement in England 1847-1981''

PhD (LSE) thesis, 1981, in particula

as on the International Vegetarian Union website.

at marxists.org

Millthorpe and Edward Carpenter

Historic England {{DEFAULTSORT:Carpenter, Edward 1844 births 1929 deaths 19th-century LGBT people 20th-century LGBT people Alumni of Trinity Hall, Cambridge Anglican socialists Anti-vivisectionists British vegetarianism activists Christ myth theory proponents English animal rights activists English Christian socialists English gay writers English libertarians English male poets English pacifists Free love advocates LGBT Anglicans LGBT rights activists from England Libertarian socialists Members of the Fabian Society People educated at Brighton College People from Hove People from North East Derbyshire District Social Democratic Federation members Socialist League (UK, 1885) members Utopian socialists

''

Henry Hyndman

Henry Mayers Hyndman (; 7 March 1842 – 20 November 1921) was an English writer, politician and socialist.

Originally a conservative, he was converted to socialism by Karl Marx's ''Communist Manifesto'' and launched Britain's first left-wing p ...

, he joined the Social Democratic Federation

The Social Democratic Federation (SDF) was established as Britain's first organised socialist political party by H. M. Hyndman, and had its first meeting on 7 June 1881. Those joining the SDF included William Morris, George Lansbury, James Con ...

(SDF) in 1883 and attempted to form a branch in the city. The group instead chose to remain independent, and became the Sheffield Socialist Society. While in the city he worked on a number of projects including highlighting the poor living conditions of industrial workers. In 1884, he left the SDF with William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

to join the Socialist League. From there he stayed with William Harrison Riley

William Harrison Riley (c.1835–1907) was an early British socialist.

Riley was born in Manchester, his father being the manager of a cloth printing factory and Methodist preacher.Edward Carpenter, ''Sketches from Life in Town and Country and ...

while he was visiting Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

.

In 1883, Carpenter published the first part of ''Towards Democracy'', a long poem expressing Carpenter's ideas about "spiritual democracy" and how Carpenter believed humanity could move towards a freer and more just society. ''Towards Democracy'' was heavily influenced by Whitman's poetry, as well as the Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

scripture, the ''Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita (; sa, श्रीमद्भगवद्गीता, lit=The Song by God, translit=śrīmadbhagavadgītā;), often referred to as the Gita (), is a 700- verse Hindu scripture that is part of the epic ''Mahabharata'' (c ...

''.Robertson, Michael, ''Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples'' Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is an independent publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Its mission is to disseminate scholarship within academia and society at large.

The press was founded by Whitney Darrow, with the financial su ...

, 2010 (pp. 179–180) Expanded editions of ''Towards Democracy'' appeared in 1885, 1892, and 1902; the complete edition of ''Towards Democracy'' was published in 1905.

In 1886–87 Carpenter was in a tender relationship with George Hukin, a razor grinder. Carpenter lived with Cecil Reddie

Dr Cecil Reddie (10 October 1858 – 6 February 1932) was a reforming English educationalist. He founded and was headmaster of the progressive Abbotsholme School.

Early life

He was born in Colehill Lodge, Fulham, London, the sixth of ten child ...

from 1888 to 1889 and in 1889 helped Reddie found Abbotsholme School

Abbotsholme School is a co-educational independent boarding and day school. The school is situated on a 140-acre campus on the banks of the River Dove in Derbyshire, England near the county border and the village of Rocester in Staffordshire ...

in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

as a notably progressive alternative to the traditional public school, with the financial support of Robert Muirhead and William Cassels

William Wharton Cassels (11 March 1858 – 7 November 1925) was an Anglican missionary bishop.

Early life and education

Cassels was born in Oporto, Portugal, the sixth son of John Cassels, a merchant, and Ethelinda Cox, a distant relation of Wa ...

.

In May 1889, Carpenter wrote a piece in the ''Sheffield Independent'' calling Sheffield the laughing-stock of the civilized world and said that the giant thick cloud of smog rising out of Sheffield was like the smoke arising from Judgment Day

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

, and that it was the altar on which the lives of many thousands would be sacrificed. He said that 100,000 adults and children were struggling to find sunlight and air, enduring miserable lives, unable to breathe and dying of related illnesses.

Travel in India

Drawn increasingly toHindu philosophy

Hindu philosophy encompasses the philosophies, world views and teachings of Hinduism that emerged in Ancient India which include six systems ('' shad-darśana'') – Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mimamsa and Vedanta.Andrew Nicholson (20 ...

, he travelled to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

in 1890. Following conversations with the guru Ramaswamy (known as the Gnani) there, he developed the conviction that socialism would bring about a revolution in human consciousness as well as of economic conditions. His account of the travel was published in 1892 as ''From Adam's Peak to Elephanta: Sketches in Ceylon and India''. The book's spiritual explorations would subsequently influence the Russian author Peter Ouspensky

Pyotr Demianovich Ouspenskii (known in English as Peter D. Ouspensky; rus, Пётр Демья́нович Успе́нский, Pyotr Demyánovich Uspénskiy; 5 March 1878 – 2 October 1947) was a Russian esotericist known for his expositions ...

, who discusses it extensively in his own book, '' Tertium Organum'' (1912).

Life with George Merrill

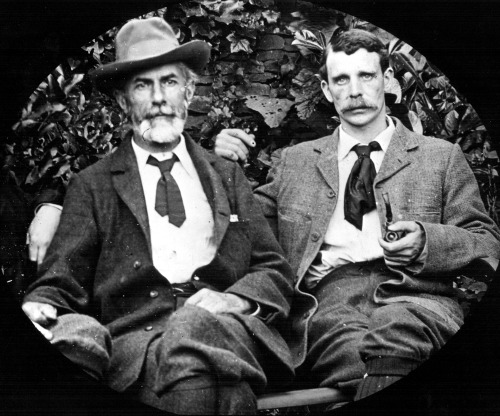

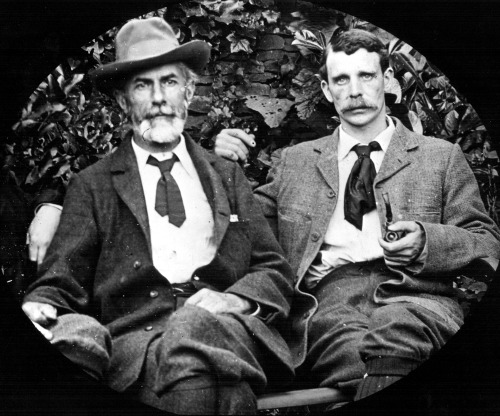

On his return from India in 1891, he met George Merrill, a working-class man also from Sheffield, 22 years his junior, and after the Ferneyhoughs left Millthorpe in 1893 Merrill became Carpenter's companion. The two remained partners for the rest of their lives, cohabiting from 1898. Merrill, the son of an engine driver, had been raised in the slums of Sheffield and had little formal education.

Carpenter remarked in his work ''The Intermediate Sex'':

On his return from India in 1891, he met George Merrill, a working-class man also from Sheffield, 22 years his junior, and after the Ferneyhoughs left Millthorpe in 1893 Merrill became Carpenter's companion. The two remained partners for the rest of their lives, cohabiting from 1898. Merrill, the son of an engine driver, had been raised in the slums of Sheffield and had little formal education.

Carpenter remarked in his work ''The Intermediate Sex'':

Eros is a great leveller. Perhaps the true Democracy rests, more firmly than anywhere else, on a sentiment which easily passes the bounds of class and caste, and unites in the closest affection the most estranged ranks of society. It is noticeable how oftenUranian Uranian may refer to: __NOTOC__ Sexuality *Uranian (sexology), a historical term for homosexual men * Uranians, a group of male homosexual poets Astronomy *Uranian, of or pertaining to the planet Uranus * Uranian system, refers to the 27 moons ...s of good position and breeding are drawn to rougher types, as of manual workers, and frequently very permanent alliances grow up in this way, which although not publicly acknowledged have a decided influence on social institutions, customs and political tendencies.Edward Carpenter ''The Intermediate Sex'', p.114-115

Carpenter included among his friends the scholar, author, naturalist, and founder of the

Carpenter included among his friends the scholar, author, naturalist, and founder of the Humanitarian League

The Humanitarian League was a British radical advocacy group formed by Henry S. Salt and others to promote the principle that it is wrong to inflict avoidable suffering on any sentient being. It was based in London and operated between 189 ...

, Henry S. Salt

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

, and his wife, Catherine; the critic, essayist and sexologist, Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality in ...

, and his wife, Edith; actor and producer Ben Iden Payne Ben Iden Payne (September 5, 1881 – April 6, 1976), also known as B. Iden Payne, was an English actor, director and teacher. Active in professional theater for seventy years, he helped the first modern Repertory Theatre in the United Kingdom, was ...

; Labour activists Bruce

The English language name Bruce arrived in Scotland with the Normans, from the place name Brix, Manche in Normandy, France, meaning "the willowlands". Initially promulgated via the descendants of king Robert the Bruce (1274−1329), it has been ...

and Katharine Glasier

Katharine Glasier (25 September 1867 – 14 June 1950) was an English socialist politician, journalist and novelist. She became a founder member of the Independent Labour Party in 1893.

Early years

Glasier was born in Stoke Newington as Kathar ...

; writer and scholar, John Addington Symonds

John Addington Symonds, Jr. (; 5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the Renaissance, as well as numerous biographies of writers and artists. Although m ...

; and the feminist writer, Olive Schreiner

Olive Schreiner (24 March 1855 – 11 December 1920) was a South African author, anti-war campaigner and intellectual. She is best remembered today for her novel ''The Story of an African Farm'' (1883), which has been highly acclaimed. It deal ...

.

E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author, best known for his novels, particularly ''A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910), and ''A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous short stori ...

was a close friend and visited the couple regularly. He later recounted that it was a visit to Millthorpe in 1913 that inspired him to write his gay-themed novel, ''Maurice Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

* Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and ...

''. Forster wrote in his terminal note to the aforementioned novel that Merrill "touched my backside – gently and just above the buttocks. I believe he touched most people's. The sensation was unusual and I still remember it, as I remember the position of a long vanished tooth. He made a profound impression on me and touched a creative spring."Sutherland, John; Fender, Stephen (2011) Love, Sex, Death & Words: Surprising Tales From a Year in Literature

', p. 160. London: Icon Books. Retrieved 11 August 2020 (Google Books) The relationship between Carpenter and Merrill was an inspiration for the relationship between Maurice Hall and Alec Scudder, the gamekeeper in ''Maurice''. The author

D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

read the manuscript of ''Maurice'', which was published posthumously in 1971. Carpenter's rural lifestyle and the manuscript influenced Lawrence's 1928 novel ''Lady Chatterley's Lover

''Lady Chatterley's Lover'' is the last novel by English author D. H. Lawrence, which was first published privately in 1928, in Italy, and in 1929, in France. An unexpurgated edition was not published openly in the United Kingdom until 1960, w ...

'' which, though built around a central relationship between a man and a woman, involves a gamekeeper and a member of the upper-class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status, usually are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper class is gen ...

.

Later life

In 1902 Carpenter's

In 1902 Carpenter's anthology

In book publishing, an anthology is a collection of literary works chosen by the compiler; it may be a collection of plays, poems, short stories, songs or excerpts by different authors.

In genre fiction, the term ''anthology'' typically categ ...

of verse and prose, '' Ioläus: An Anthology of Friendship'', was published.The 1917 New York edition is now available as a free e-book The book was published again in 1906 by William Swan Sonnenschein

William Swan Sonnenschein (5 May 1855 – 31 January 1931), known from 1917 as William Swan Stallybrass, was a British publisher, editor and bibliographer. His publishing firm, Swan Sonnenschein, published scholarly works in the fields of philo ...

.

In 1915, he published ''The Healing of Nations and the Hidden Sources of Their Strife'', where he argued that the source of war and discontent in western society was class-monopoly and social inequality.

Carpenter became an advocate of the Christ myth theory

The Christ myth theory, also known as the Jesus myth theory, Jesus mythicism, or the Jesus ahistoricity theory, is the view that "the story of Jesus is a piece of mythology", possessing no "substantial claims to historical fact". Alternatively ...

. His book ''Pagan and Christian Creeds'' was published by Harcourt, Brace and Howe

Harcourt () was an American publishing firm with a long history of publishing fiction and nonfiction for adults and children. The company was last based in San Diego, California, with editorial/sales/marketing/rights offices in New York City a ...

in 1921.

The death of George Hukin in 1917 at the age of 56 seems to have broken Carpenter's attachment to the North of England. In 1922 he and Merrill moved to Guildford

Guildford ()

is a town in west Surrey, around southwest of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The name "Guildf ...

, Surrey Brighton Ourstory Project – Lesbian and Gay History Groupat www.brightonourstory.co.uk and the two lived at 23 Mountside Rd. On Carpenter's 80th birthday he was presented an album signed by every member of the then

Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

Government, headed by Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

, Prime Minister, who Carpenter had known since his teenage years.

In January 1928, Merrill died suddenly, having become dependent on alcohol since moving to Surrey. Carpenter was devastated and he sold their house and lodged for a short time, with his companion and carer Ted Inigan, at 17 Wodeland Avenue, just a short walk from Mountside. They then moved to a bungalow called 'Inglenook' in Josephs Road. In May 1928, Carpenter suffered a paralytic stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

. He lived another 13 months before he died on 28 June 1929, aged 84. He was interred in the same grave as Merrill at the Mount Cemetery in Guildford under a lengthy invocation written by Carpenter.

His obituary in The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

was headed "Edward Carpenter, Author and Poet", though the text did also refer to his political campaigns.

Influence

Carpenter corresponded with many leading figures in political and cultural circles, among themAnnie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

, Isadora Duncan

Angela Isadora Duncan (May 26, 1877 or May 27, 1878 – September 14, 1927) was an American dancer and choreographer, who was a pioneer of modern contemporary dance, who performed to great acclaim throughout Europe and the US. Born and raised in ...

, Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality in ...

, Roger Fry

Roger Eliot Fry (14 December 1866 – 9 September 1934) was an English painter and critic, and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Establishing his reputation as a scholar of the Old Masters, he became an advocate of more recent developme ...

, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

, Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

, George Merrill, E. D. Morel

Edmund Dene Morel (born Georges Edmond Pierre Achille Morel Deville; 10 July 1873 – 12 November 1924) was a French-born British journalist, author, pacifist and politician.

As a young official at the shipping company Elder Dempster, Morel ob ...

, William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

, Edward R. Pease

Edward Reynolds Pease (23 December 1857 – 5 January 1955) was an English writer and a founding member of the Fabian Society.

Early life

Pease was born near Bristol, the son of devout Quakers, Thomas Pease (1816–1884) and Susanna Ann Fr ...

, John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and politi ...

, and Olive Schreiner

Olive Schreiner (24 March 1855 – 11 December 1920) was a South African author, anti-war campaigner and intellectual. She is best remembered today for her novel ''The Story of an African Farm'' (1883), which has been highly acclaimed. It deal ...

."Fabian Economic and Social Thought Series One: The Papers of Edward Carpenter, 1844-1929", from Sheffield Archives Part 1: Correspondence and Manuscriptsat www.adam-matthew-publications.co.uk

Carpenter was a friend of

Carpenter was a friend of Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

, and of Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

. Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxley ...

recommended Carpenter's pamphlet ''Civilization: Its Cause and Cure'' in his book '' Science, Liberty and Peace''. Modernist art critic Herbert Read

Sir Herbert Edward Read, (; 4 December 1893 – 12 June 1968) was an English art historian, poet, literary critic and philosopher, best known for numerous books on art, which included influential volumes on the role of art in education. Read ...

credited Carpenter's pamphlet ''Non-Governmental Society'' with converting him to anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

.

Leslie Paul

Leslie Allen Paul (1905, Dublin – 1985, Cheltenham) was an Anglo-Irish writer and founder of the Woodcraft Folk.

__TOC__

Life

Early life

Born in Dublin on 30 April 1905, Leslie Paul grew up in Honor Oak, the second child of advertising m ...

was influenced by Carpenter's work; in turn he passed on Carpenter's ideas to the scouting group he founded, The Woodcraft Folk

Woodcraft Folk is a UK-based educational movement for children and young people. Founded in 1925 and grown by volunteers, it has been a registered charity since 1965 Registered Charity since 2013. and a registered company limited by guarantee s ...

. Algernon Blackwood

Algernon Henry Blackwood, CBE (14 March 1869 – 10 December 1951) was an English broadcasting narrator, journalist, novelist and short story writer, and among the most prolific ghost story writers in the history of the genre. The literary cri ...

was another devotee of Carpenter's work; Blackwood corresponded with Carpenter and included a quotation from ''Civilization: Its Cause and Cure'' in his 1911 novel ''The Centaur''.

Fenner Brockway

Archibald Fenner Brockway, Baron Brockway (1 November 1888 – 28 April 1988) was a British socialist politician, humanist campaigner and anti-war activist.

Early life and career

Brockway was born to W. G. Brockway and Frances Elizabeth Abbey in ...

, in a 1929 obituary of Carpenter, acknowledged him as an influence on Brockway and his associates when young. Brockway described Carpenter as "the greatest spiritual inspiration of our lives. ''Towards Democracy'' was our Bible." Ansel Adams

Ansel Easton Adams (February 20, 1902 – April 22, 1984) was an American landscape photographer and environmentalist known for his black-and-white images of the American West. He helped found Group f/64, an association of photographers advoca ...

was an admirer of Carpenter's writings, especially ''Towards Democracy''.Spaulding, Jonathan,''Ansel Adams and the American Landscape: A Biography'', Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998. (p.49) Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

cited Carpenter's books as an influence on her thought, and stated that Carpenter possessed "the wisdom of the sage." Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen (born Countee LeRoy Porter; May 30, 1903 – January 9, 1946) was an American poet, novelist, children's writer, and playwright, particularly well known during the Harlem Renaissance.

Early life

Childhood

Countee LeRoy Porter ...

said that reading Carpenter's book ''Iolaus'' "opened up for me soul windows which had been closed".

Carpenter was sometimes called "the English Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

" and Tolstoy himself considered him "a worthy heir of Carlyle and Ruskin".

Revival of reputation

Following his death, Carpenter's written works fell out of print and were largely forgotten except among devotees of British labour movement history. However, in the 1970s and 1980s, interest in his work was revived by historians such as Jeffrey Weeks andSheila Rowbotham

Sheila Rowbotham (born 27 February 1943) is a British socialist feminist theorist and historian. Early life

Rowbotham was born on 27 February 1943 in Leeds (in present-day West Yorkshire), the daughter of a salesman for an engineering company a ...

, and some of Carpenter's works were reprinted by the Gay Men's Press

Gay Men's Press was a publisher of books based in London, United Kingdom. Founded in 1979, the imprint was run until 2000 by its founders, then until 2006 by Millivres Prowler.

Overview

Launched in 1979 by Aubrey Walter, David Fernbach, and Rich ...

. Carpenter's opposition to pollution

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into the natural environment that cause adverse change. Pollution can take the form of any substance (solid, liquid, or gas) or energy (such as radioactivity, heat, sound, or light). Pollutants, the ...

and cruelty to animals have resulted in some historians arguing Carpenter's ideas anticipated the modern Green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 Nanometre, nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by ...

and animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding suffering—should be afforded the sa ...

movements. Carpenter was described by Fiona MacCarthy

Fiona MacCarthy (23 January 1940 – 29 February 2020) was a British biographer and cultural historian best known for her studies of 19th- and 20th-century art and design.

Early life and education

Fiona MacCarthy was born in Sutton, Surrey in ...

as the "Saint in Sandals", the "Noble Savage" and, more recently, the "gay godfather of the British left".

Written works

''Chants of Labour'' was a songbook for socialists, contributions to which Carpenter had solicited in '' The Commonweal''. It comprised works by John Glasse,Edith Nesbit

Edith Nesbit (married name Edith Bland; 15 August 1858 – 4 May 1924) was an English writer and poet, who published her children's literature, books for children as E. Nesbit. She wrote or collaborated on more than 60 such books. She was also ...

, John Bruce Glasier

John Bruce Glasier (25 March 1859 – 4 June 1920) was a Scottish socialist politician, associated mainly with the Independent Labour Party. He was opposed to the First World War.

Biography

Glasier was born in Glasgow as John Bruce, but grew u ...

, Andreas Scheu, William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

, Jim Connell

Jim Connell (27 March 1852 – 8 February 1929) was an Irish political activist of the late 19th century and early 20th century, best known as the writer of the anthem " The Red Flag" in December 1889.

Life

Connell was born in the townland of R ...

, Herbert Burrows, and others.

See also

* List of Christ myth theory proponentsReferences

Bibliography

* * Beith, Gilbert (ed), ''Edward Carpenter: In Appreciation'', George Allen & Unwin, 1931. * * * * Greig, Noël: ''Dear Love of Comrades'': London: Gay Men's Press, 1979. * Lewis, Edward, ''Edward Carpenter: An Exposition and an Appreciation'', Macmillan, 1915. * Stanley Pierson, "Edward Carpenter, Prophet of a Socialist Millennium," ''Victorian Studies,'' vol. 13, no. 3 (March 1970), pp. 301–318. * * * * Tsuzuki, Chushchi, ''Edward Carpenter 1844-1929 Prophet of Human Fellowship'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980. * Twigg, Juli''The Vegetarian Movement in England 1847-1981''

PhD (LSE) thesis, 1981, in particula

as on the International Vegetarian Union website.

External links

* *at marxists.org

Millthorpe and Edward Carpenter

Historic England {{DEFAULTSORT:Carpenter, Edward 1844 births 1929 deaths 19th-century LGBT people 20th-century LGBT people Alumni of Trinity Hall, Cambridge Anglican socialists Anti-vivisectionists British vegetarianism activists Christ myth theory proponents English animal rights activists English Christian socialists English gay writers English libertarians English male poets English pacifists Free love advocates LGBT Anglicans LGBT rights activists from England Libertarian socialists Members of the Fabian Society People educated at Brighton College People from Hove People from North East Derbyshire District Social Democratic Federation members Socialist League (UK, 1885) members Utopian socialists