Edgar Ray Killen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edgar Ray Killen (January 17, 1925 – January 11, 2018) was an American

During the "

During the "

Killen entered the

Killen entered the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

organizer who planned and directed the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

activists participating in the Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer, also known as the Freedom Summer Project or the Mississippi Summer Project, was a volunteer campaign in the United States launched in June 1964 to attempt to register as many African-American voters as possible in Mississippi. ...

of 1964. He was found guilty in state court of three counts of manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

on June 21, 2005, the forty-first anniversary of the crime, and sentenced to 60 years in prison. He appealed the verdict, but the sentence was upheld on April 12, 2007, by the Supreme Court of Mississippi

The Supreme Court of Mississippi is the highest court in the state of Mississippi. It was established in the first constitution of the state following its admission as a State of the Union in 1817 and was known as the High Court of Errors and Appe ...

. He died in prison on January 11, 2018, six days before his 93rd birthday.

Early life

Edgar Ray Killen was born inPhiladelphia, Mississippi

Philadelphia is a city in and the county seat of Neshoba County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 7,118 at the 2020 census.

History

Philadelphia is incorporated as a municipality; it was given its current name in 1903, two year ...

, as the oldest of eight children to Lonie Ray Killen (1901–1992) and Jetta Killen (née Hitt; 1903–1983). Killen was a sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes (dimensi ...

operator and a part-time Baptist minister. He was a kleagle, or klavern recruiter and organizer, for the Neshoba and Lauderdale County chapters of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

.

Murders

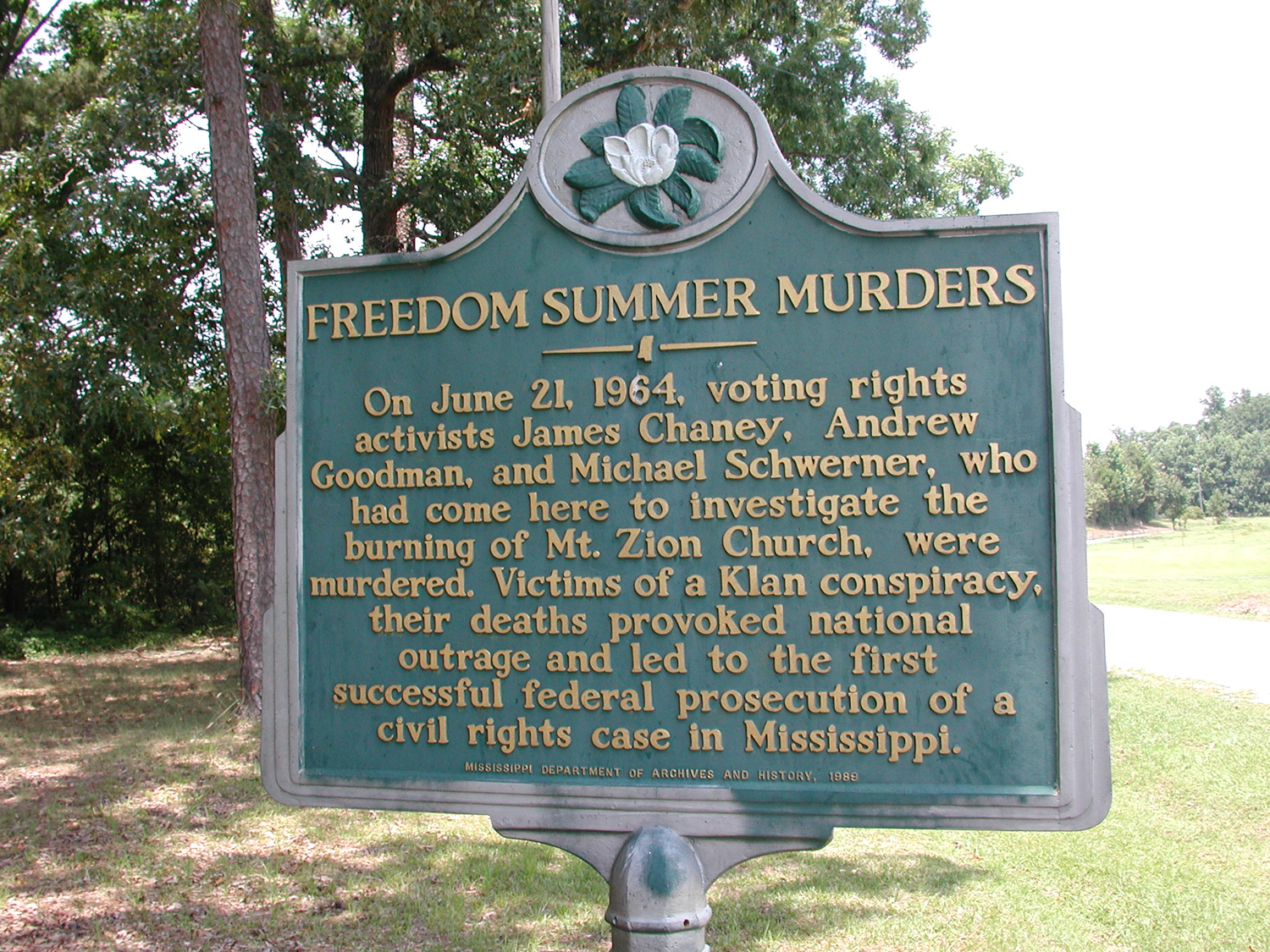

Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer, also known as the Freedom Summer Project or the Mississippi Summer Project, was a volunteer campaign in the United States launched in June 1964 to attempt to register as many African-American voters as possible in Mississippi. ...

" of 1964, James Chaney

James Earl Chaney (May 30, 1943 – June 21, 1964) was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) civil rights workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan on June 21, 1964. The others were Andrew Goodman an ...

, 21, a young black man from Meridian, Mississippi

Meridian is the List of municipalities in Mississippi, seventh largest city in the U.S. state of Mississippi, with a population of 41,148 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census and an estimated population in 2018 of 36,347. It is the count ...

, and Andrew Goodman, 20, and Michael Schwerner, 24, two Jewish men from New York, were murdered in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Killen, along with deputy sheriff of Neshoba County Cecil Price

Cecil Ray Price (April 15, 1938 – May 6, 2001) was accused of the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in 1964. At the time of the murders, he was 26 years old and a deputy sheriff in Neshoba County, Mississippi. He was a member of the Wh ...

, was found to have assembled a group of armed men who conspired against, pursued, and killed the three civil rights workers. Samuel Bowers

Samuel Holloway Bowers (August 25, 1924 – November 5, 2006) was a convicted murderer and a leading white supremacist in Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement. He was Grand Dragon of the Mississippi Original Knights of the Ku Klux Kla ...

, who served as the Grand Wizard

The Grand Wizard (later the Grand and Imperial Wizard simplified as the Imperial Wizard and eventually, the National Director) referred to the national leader of several different Ku Klux Klan organizations in the United States and abroad.

The ti ...

of the local White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

The White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan is a Ku Klux Klan organization which is active in the United States. It originated in Mississippi and Louisiana in the early 1960s under the leadership of Samuel Bowers, its first Imperial Wizard. The White K ...

and had ordered the murders to take place, acknowledged that Killen was "the main instigator".

At the time of the murders, the state of Mississippi made almost no effort to prosecute the guilty parties. Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

and the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

(FBI), under President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, conducted a vigorous investigation. Circumventing dismissals by federal judges, federal prosecutor John Doar

John Michael Doar (December 3, 1921 – November 11, 2014) was an American lawyer and senior counsel with the law firm Doar Rieck Kaley & Mack in New York City. During the administrations of presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, he ...

convened a grand jury

A grand jury is a jury—a group of citizens—empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a pe ...

in December 1964. In November 1965 Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

appeared before the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

to defend the federal government's authority in bringing charges. Eighteen men, including Killen, were arrested and charged with conspiracy to violate the victims' civil rights in '' United States v. Price''.

The trial, which began in 1966 at the federal courthouse of Meridian

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

before an all-white jury

Racial discrimination in jury selection is specifically prohibited by law in many jurisdictions throughout the world. In the United States, it has been defined through a series of judicial decisions. However, juries composed solely of one racial ...

, convicted seven conspirators, including the deputy sheriff, and acquitted eight others. It was the first time a white jury convicted a white official of civil rights killings.Campbell Robertson, "Last Chapter for a Courthouse Where Mississippi Faced Its Past", ''New York Times'', September 18, 2012, pp. 1, 16 For three men, including Killen, the trial ended in a hung jury

A hung jury, also called a deadlocked jury, is a judicial jury that cannot agree upon a verdict after extended deliberation and is unable to reach the required unanimity or supermajority. Hung jury usually results in the case being tried again.

...

, with the jurors deadlocked 11–1 in favor of conviction. The lone holdout said that she could not convict a preacher. The prosecution decided not to retry Killen and he was released. None of the men found guilty would serve more than six years in prison.

More than 20 years later, Jerry Mitchell

Jerry Mitchell is an American theatre director and choreographer.

Early life and education

Born in Paw Paw, Michigan, Mitchell later moved to St. Louis where he pursued his acting, dancing and directing career in theatre. Although he did not ...

, an award-winning investigative reporter for ''The Clarion-Ledger

''The Clarion Ledger'' is an American daily newspaper in Jackson, Mississippi. It is the second-oldest company in the state of Mississippi, and is one of the few newspapers in the nation that continues to circulate statewide. It is an operating d ...

'' in Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson, officially the City of Jackson, is the Capital city, capital of and the List of municipalities in Mississippi, most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi. The city is also one of two county seats of Hinds County, Mississippi, ...

, wrote extensively about the case for six years. Mitchell helped to secure convictions in other high-profile Civil Rights Era murder cases, including the assassination of Medgar Evers

Medgar Wiley Evers (; July 2, 1925June 12, 1963) was an American civil rights activist and the NAACP's first field secretary in Mississippi, who was murdered by Byron De La Beckwith. Evers, a decorated U.S. Army combat veteran who had served i ...

, the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, and the murder of Vernon Dahmer

Vernon Ferdinand Dahmer Sr. (March 10, 1908 – January 10, 1966) was an American civil rights movement leader and president of the Forrest County chapter of the NAACP in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He was murdered by the White Knights of ...

. Mitchell assembled new evidence regarding the murders of the three civil rights workers. He also located new witnesses and pressured the state to take action. Assisting Mitchell were high school teacher Barry Bradford and a team of three students from Illinois.

The students persuaded Killen to do his only taped interview (to that point) about the murders. The tape showed Killen competent, aware, and clinging to his segregationist

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Interna ...

views. The student-teacher team found more potential witnesses, created a website, lobbied the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

, and focused national media attention on reopening the case. Carolyn Goodman, the mother of one of the victims, called them "super heroes".

The film ''Mississippi Burning

''Mississippi Burning'' is a 1988 American crime thriller film directed by Alan Parker that is loosely based on the 1964 murder investigation of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in Mississippi. It stars Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe as two FBI ...

'' is related to the murders.

Reopening of the case

In early January 2004, a multiracial group of citizens in Neshoba County formed the Philadelphia Coalition, to seek justice for the 1964 murders. Led by co-chairs Leroy Clemons and Jim Prince, the group met over several months and then issued a call for justice, first in March 2004 and then on June 21, the 40th anniversary of the murders. That event was attended by over 1500 people. The sitting Mississippi governor was present and four congressmen, including Rep. John Lewis and Rep.Bennie Thompson

Bennie Gordon Thompson (born January 28, 1948) is an American politician serving as the U.S. representative for since 1993. A member of the Democratic Party, Thompson has been the chair of the Committee on Homeland Security since 2019 and from ...

. Former Mississippi Secretary of State Dick Molpus made a lauded speech imploring those with information about the crimes to come forward. The Coalition met over the summer with state attorney general Jim Hood, along with Andrew Goodman's mother Carolyn Goodman and brother David Goodman. They asked Hood to re-open the case. The group also met with local district attorney Mark Duncan. The group was supported throughout by the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation. In the fall of 2004, an anonymous donor provided funds through the Mississippi Religious Leadership Council for anyone with information leading to an arrest.

On January 6, 2005, AG Hood and DA Duncan convened a local grand jury, which indicted Edgar Ray Killen for the murders.

In 2004, Killen said he would attend a petition-drive on his behalf, conducted by the Nationalist Movement

The Nationalist Movement is a Mississippi-founded white nationalist organization with headquarters in Georgia that advocates what it calls a "pro-majority" position. It has been called white supremacist by the Associated Press and Anti-Defamati ...

at the 2004 Mississippi Annual State Fair in Jackson. The Nationalist Movement is a white supremacy organization. Hinds County

Hinds County is a county located in the U.S. state of Mississippi. With its county seats ( Raymond and the state's capital, Jackson), Hinds is the most populous county in Mississippi with a 2020 census population of 227,742 residents. Hinds Cou ...

sheriff Malcolm McMillin conducted a counter-petition calling for a reopening of the state case against Killen. Killen was arrested for three counts of murder on January 6, 2005. He was freed on bond.

Killen's trial was scheduled for April 18, 2005. It was deferred after the 80-year-old Killen broke both legs while chopping lumber. The trial began on June 13, 2005, with Killen attending in a wheelchair

A wheelchair is a chair with wheels, used when walking is difficult or impossible due to illness, injury, problems related to old age, or disability. These can include spinal cord injuries ( paraplegia, hemiplegia, and quadriplegia), cerebr ...

. He was found guilty of manslaughter on June 21, 2005, 41 years to the day after the crime. The jury of nine white jurors and three black jurors rejected the murder charges but found him guilty of manslaughter for recruiting the mob that carried out the killings. He was sentenced on June 23, 2005, by Circuit Judge Marcus Gordon to the maximum sentence of 60 years in prison, 20 years for each count of manslaughter, to be served consecutively. He would have been eligible for parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

after 20 years. In his sentencing remarks Gordon said that each life lost was valuable, that the law made no distinction of age for the crime, and that the maximum sentence should be imposed regardless of Killen's age. Prosecuting the case were Mississippi Attorney General

The Attorney General of Mississippi is the chief legal officer of the state and serves as the state's lawyer. Only the Attorney General can bring or defend a lawsuit on behalf of the state.

The Attorney General is elected statewide for a four-yea ...

Jim Hood

James Matthew Hood (born May 15, 1962) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 39th Attorney General of Mississippi from 2004 to 2020.

A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he was first elected in 20 ...

and Neshoba County District Attorney Mark Duncan.

Incarceration and death

Mississippi Department of Corrections

The Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) is a state agency of Mississippi that operates prisons. It has its headquarters in Jackson. Burl Cain is the commissioner.

History

In 1843 a penitentiary in four city squares in central Jackson ...

system on June 27, 2005, to serve his sixty-year sentence. On August 12 he was released on a $600,000 appeal bond, having claimed he could not use his right hand (using his left hand to place his right hand on the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

during swearing-in) and that he was permanently confined to his wheelchair. Judge Gordon said he was convinced Killen was neither a flight risk nor a danger to the community. On September 3, ''The Clarion-Ledger

''The Clarion Ledger'' is an American daily newspaper in Jackson, Mississippi. It is the second-oldest company in the state of Mississippi, and is one of the few newspapers in the nation that continues to circulate statewide. It is an operating d ...

'' reported that a deputy sheriff saw Killen walking around "with no problem". At a hearing on September 9, several other deputies testified to seeing Killen driving in various locations. One deputy said Killen shook hands with him using his right hand. Gordon revoked the bond and ordered Killen back to prison, saying Killen had committed a fraud against the court.

Killen's request for a new trial was denied by a circuit court judge and he was transferred to the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility

The Central Mississippi Correctional Facility for Women (CMCF) is a Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) prison for men and women located in an unincorporated area in Rankin County, Mississippi, near the city of Pearl.Pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle) of a living shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pearl is composed of calcium carb ...

. On March 29, 2006, Killen was moved to a City of Jackson hospital to treat complications of his leg injury sustained in the 2005 logging incident. On August 12, 2007, the Supreme Court of Mississippi

The Supreme Court of Mississippi is the highest court in the state of Mississippi. It was established in the first constitution of the state following its admission as a State of the Union in 1817 and was known as the High Court of Errors and Appe ...

affirmed Killen's conviction by a vote of 8–0 (one judge not participating).

In February 2010, Killen filed a lawsuit against the FBI alleging that one of his lawyers in his 1967 trial, Clayton Lewis, was an FBI informant, and that the FBI had hired "gangster and killer" Gregory Scarpa

Gregory Scarpa (May 8, 1928 – June 4, 1994) nicknamed the Grim Reaper and also the Mad Hatter, was an American caporegime and hitman for the Colombo crime family, as well as an informant for the FBI. During the 1970s and 80s, Scarpa was the ...

to coerce witnesses. On March 23, 2011, District Judge Daniel P. Jordan III adopted Magistrate F. Keith Ball's recommendation to dismiss the case.

James Hart Stern, a black preacher from California, shared a prison cell with Edgar Ray Killen from August 2010 to November 2011 while serving time for wire fraud. Killen and Stern forged a close relationship, and Killen wrote dozens of letters to Stern outlining his views on race and confessing to other crimes. He also signed over his land in Mississippi to Stern and gave him power of attorney. Stern detailed his experience in the 2017 book ''Killen the KKK,'' co-authored by Autumn K. Robinson. On January 5, 2016, Stern used his power of attorney to dissolve Killen's branch of the KKK.

Killen died on January 11, 2018, at the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi, six days before his 93rd birthday.

See also

*Civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

* ''Neshoba'' (film)

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Killen, Edgar Ray 1925 births 2018 deaths Civil rights movement People from Philadelphia, Mississippi Ku Klux Klan members in the United States American people convicted of manslaughter American people who died in prison custody Prisoners who died in Mississippi detention 20th-century American trials Southern Baptists Murder trials Ku Klux Klan crimes in Mississippi Baptists from Mississippi 20th-century Baptists