Economic History Of Greece And The Greek World on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The economic history of the Greek World spans several millennia and encompasses many modern-day nation states.

Since the focal point of the center of the Greek World often changed it is necessary to enlarge upon all these areas as relevant to the time. The economic history of Greece refers to the economic history of the Greek nation state since 1829.

(eBook) The series of wars between 1912 and 1922 provided a catalyst for Greek industry, with a number of industries such as textiles; ammunition and boot-making springing up to supply the military. After the wars most of these industries were converted to civilian uses.

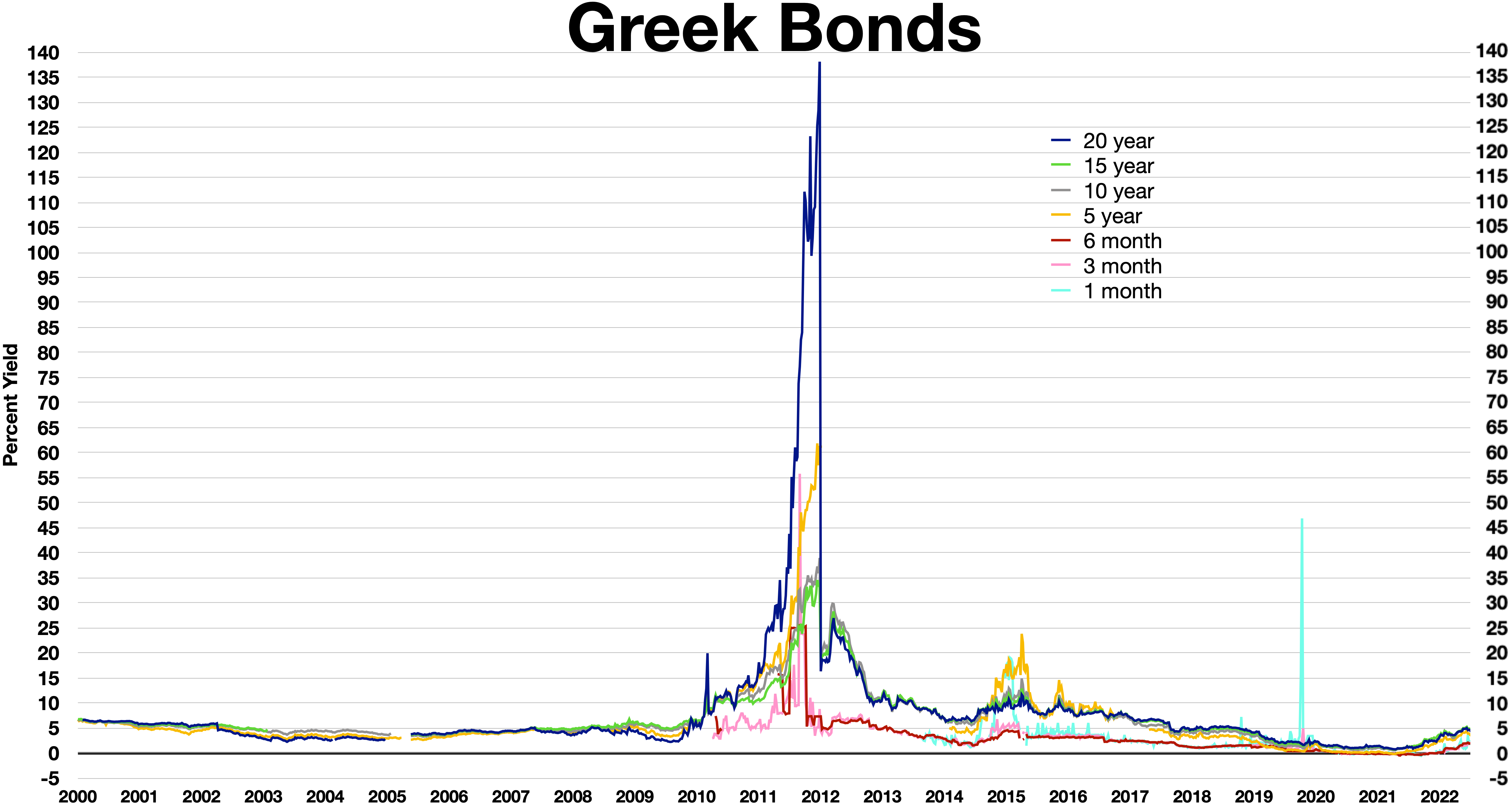

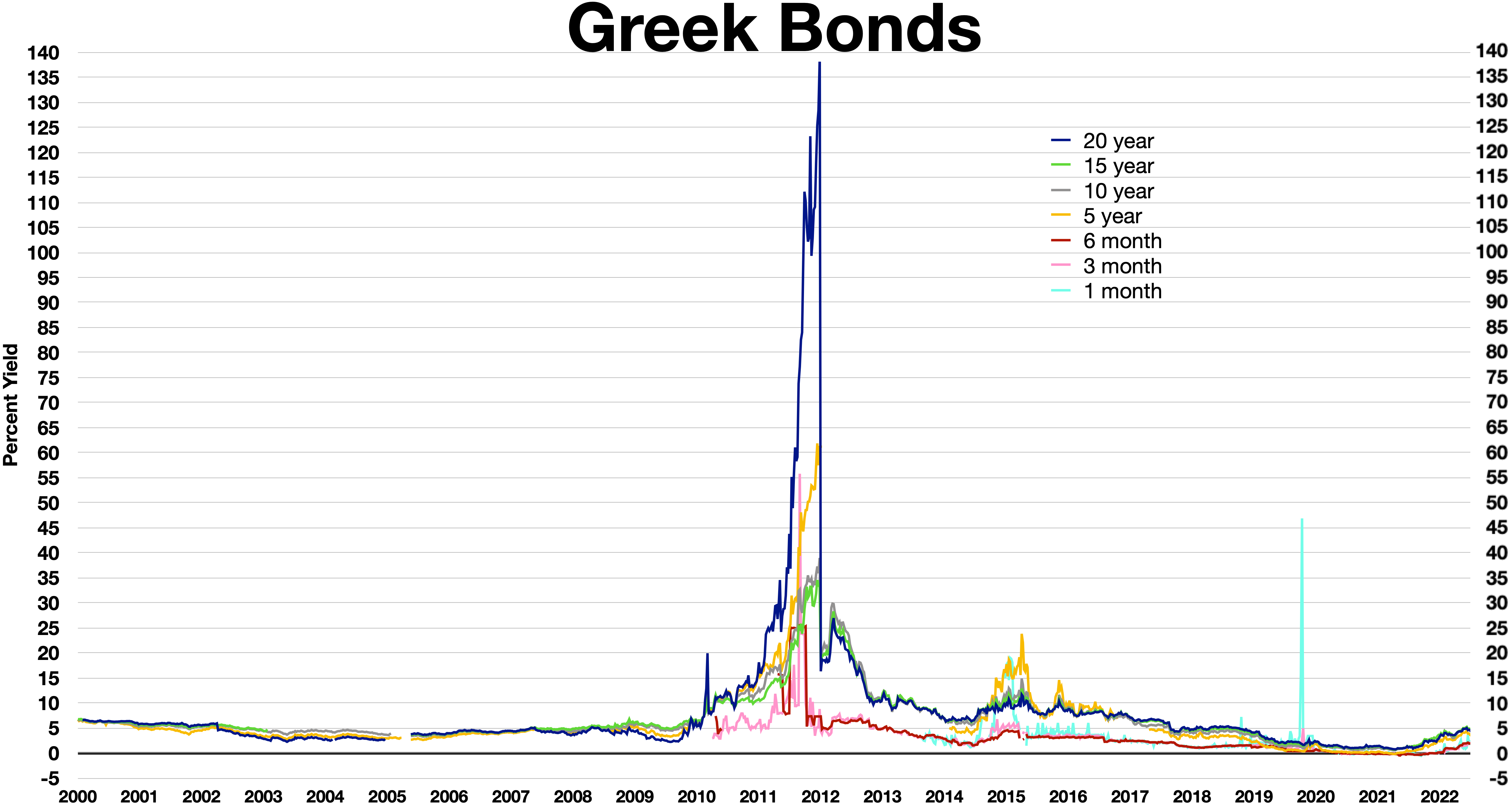

Greek economy had fared well for much of the 20th century, with high growth rates and low public debt. As a result of internal and external factors (mainly, the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008), the country entered a prolonged recession in 2008 and, after a significant rise in its borrowing costs, by April 2010 the government realized that it would need a rescue package. Greece had the biggest sovereign debt restructuring in history in 2012. In April 2014, Greece returned to the global bond market as it successfully sold €3 billion worth of five-year government bonds at a yield of 4.95%. Greece had real GDP growth of 0.7% in 2014 after 5 years of decline. After a third bailout in 2015 (following the election of the leftist SYRIZA Party), Greece bailouts ended successfully (as declared) on August 20, 2018.

Greek economy had fared well for much of the 20th century, with high growth rates and low public debt. As a result of internal and external factors (mainly, the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008), the country entered a prolonged recession in 2008 and, after a significant rise in its borrowing costs, by April 2010 the government realized that it would need a rescue package. Greece had the biggest sovereign debt restructuring in history in 2012. In April 2014, Greece returned to the global bond market as it successfully sold €3 billion worth of five-year government bonds at a yield of 4.95%. Greece had real GDP growth of 0.7% in 2014 after 5 years of decline. After a third bailout in 2015 (following the election of the leftist SYRIZA Party), Greece bailouts ended successfully (as declared) on August 20, 2018.

Earliest Greek civilizations

Cycladic civilization

Cycladic civilization

Cycladic culture (also known as Cycladic civilisation or, chronologically, as Cycladic chronology) was a Bronze Age culture (c. 3200–c. 1050 BC) found throughout the islands of the Cyclades in the Aegean Sea. In chronological terms, it is a rel ...

is the earliest trading center of goods. It was extensively distributed throughout the Aegean region.

Minoan civilization

The Minoan civilization emerged on Crete around the time the earlyBronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, it had a wide range of economic interests and was something of a trade hub, exporting many items to mainland Greece as well as the Egyptian Empire of the period. The Minoans were also innovators, developing (or adopting) a system of lead weights to facilitate economic transactions. Despite this Minoan civilization remained, for the most part, an agriculturally driven one.

pigs and artists were an important part of the Minoan economy as they produced many goods that were valued in trade as well as within Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

itself. The Linear B tablets often refer to men or to their work, although, there were also female artisans, who mainly worked in the textile industry. We also know from archaeological evidence that Minoan artisans practised a large range of craftsmanship jobs including: scribes, potters, metalworkers, leather workers, glass and faience artists, painters, sculptors, engravers and jewelers. Due to only a small amount of evidence about occupation, we do not know whether a worker might have mastered in several trades, or fully specialized in one profession. There was an area set aside for artisans and their workshops in every palace, and in town like Malia, they had both workshops in town and in the palace.

The production of oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

was an important activity in which Minoan artisans were engaged. There were a large number of oil jars found in the destroyed palaces that tell us of the importance of this industry. Oil was an extremely important part of the perfume industry as it was used to clean dirt from the body, much like soap does today. Perfumes were also sprinkled on clothing, for aesthetic reasons. It is certain that perfumes were a luxury item

In economics, a luxury good (or upmarket good) is a good for which demand increases more than what is proportional as income rises, so that expenditures on the good become a greater proportion of overall spending. Luxury goods are in contrast to n ...

of Minoan trade.

The bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

industries were also an important aspect of the Minoan economy and the art of bronze making was very common, suggested by the fact that evidence of bronze making was discovered in many towns, such as Phaistos

Phaistos ( el, Φαιστός, ; Ancient Greek: , , Minoan: PA-I-TO?http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/download/11991/4031&ved=2ahUKEwjor62y3bHoAhUEqYsKHZaZArAQFjASegQIAhAB&usg=AOvVaw1MwIv3ekgX-SxkJrbORipd ), also transliterated as Phaestos, ...

and Zakro Zakros ( el, Ζάκρος; Linear B: zakoro) is a site on the eastern coast of the island of Crete, Greece, containing ruins from the Minoan civilization. The site is often known to archaeologists as Zakro or Kato Zakro. It is believed to have been ...

, but also as evidence in the area of Malia show that bronze making operations were flourishing in many of the palaces. It is believed that the Minoans imported tin and copper to make bronze ingots for other people. Evidence of this is shown in Egyptian tomb paintings where the Keftyw (people believed to be the Minoans) bring said ingots to the Egyptian king in gift exchange (The Egyptians and Minoans had a history of cultural exchange). Other objects made from bronze have been found in numbers at Knossos, these include bronze mirrors, labrys, votive figures, knives, cleavers and small bronze tools.

The stone carving industry produced many vases and lamps, examples of which have been found at palaces and palatial villas throughout Minoan Crete. Another industry that contributed to the Minoan economy was the wine industry, which is mentioned in Linear A, but the small amounts referred to suggest it was a commodity reserved for the wealthier class.

Mycenaean civilization

TheMycenaean civilization

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland ...

emerged during the late Bronze Age, supplanting the Minoans as the dominant economic force in the area. The Mycenaean economy itself was based on agriculture. The tablets from both Pylos

Pylos (, ; el, Πύλος), historically also known as Navarino, is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is th ...

and Knossos demonstrate that there were two major food-grains produced; wheat and barley.

Agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

was highly organised and this becomes apparent by the written records of deliveries of land produce, taxes in kind due to the palace, a hare set aside for the gods and so forth. The land used for agriculture was basically of two types, represented by the terms ''ko-to-na'' (ktoina) ''ki-ti-me-na'' and ''ko-to-na ke-ke-me-na''. The former refers to the privately owned land, the latter to the public one (owned by the damos). Cereals were used as the basis of the rations’ system both at Knossos and Pylos. At Knossos, for example, the rations are quoted for a work-group composed of 18 men and 8 boys as 97.5 units of barley.

Apart from cereals, the Mycenaeans also produced wine, olive oil, oil from various spices and figs. As far as wine is concerned, it does not figure in the ordinary ration lists and may have been something of a luxury or possibly for export. Mycenaean trade was very advanced and there is even evidence of an amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In Ma ...

trade from Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

Metals

A metal (from Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typicall ...

were also a very important part of the Mycenaean economy, during the Mycenaean period there were five metals in use: gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

, silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

, tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

and lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

. Iron was not unknown but was very rare. Therefore, bronze was the main metal for the making of tools and weapons. Although bronze was the most important metal for the Mycenaeans, it was relatively scarce and expensive. Our knowledge of the Mycenaean bronze industry comes entirely from Pylos where we have some information about smiths. Most of the tablets concerning bronze demonstrate a very tight control of the metal industry by the palace.

Ancient Greece and the emergence of the 'Polis'

Greece's "Dark Ages"

The Greek Dark Ages were a period of economic stagnation for the Greeks after the destruction of the complex Mycenaean economic system, the loss of the widespread written scriptLinear B

Linear B was a syllabic script used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of Greek. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries. The oldest Mycenaean writing dates to about 1400 BC. It is descended from ...

meant that development was effectively stunted and living standards deteriorated. Basic trading patterns remained however.

City States

The emergence of the 'Polis' as the model for ideal governance following the end of the Greek Dark Ages heavily influenced the economy of the Greeks at the time. This period, of the 8th century BCE to the 4th century BCE is conventionally termed as 'Ancient Greece'. The main issues concerning the ancient Greek economy are related to the household (oikos) organization, the cities’ legislation and the first economic institutions, the invention of coinage and the degree of monetization of theGreek economy

The economy of Greece is the 53rd largest in the world, with a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of $222.008 billion per annum. In terms of purchasing power parity, Greece is the world's 54th largest economy, at $387.801 billion per annum ...

, the trade and its crucial role in the characterization of the economy (modernism vs. primitivism), the invention of banking and the role of slavery in the production.

Athens

Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

emerged as the dominant economic power in Greece around the late 6th century BCE, this was further bolstered by the finding of several veins of silver in the neighbouring mountains which further added to their wealth. They facilitated an efficient trading system with other Greek city states. Again, pots and other forms of cooking utensils seem to have been the most quantitatively traded product (over 80,000 amphorae and other such things have been recovered from around Athens in archaeological digs). Marble and bronze artwork also seems to have been traded (though it was largely a luxury product, and this trade only really exploded after the rise of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

, as Greek Art exerted a massive influence on Roman Culture on all levels). Athens began to import grain due to poor soil conditions however.

The agricultural conditions which caused Athens to import grain began to create political turmoil around 600 BCE It is believed that tenant farmers were paying rent equivalent to a sixth of their production, hence they were known as "sixth-parters." Those who could not pay their rent could be sold by the landlord into slavery. In 594 Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politics'' ...

(one of the great reformers of Athens) would order the cancellation of debt and the freeing of those sold into slavery, a proclamation known as the ''"Seisactheia."'' While Solon's proclamation was a bold move, it could not really solve the problem of meager agricultural output and competition between workers for jobs. Debt and slavery, while problems in themselves, were also symptomatic of underlying agricultural problems.

From an economic perspective, poor soil was only one problem Athens had to deal with. There are indications that unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for Work (human activity), w ...

was a substantial and on-going problem for much of Athens' history. Solon's reforms encouraged economic diversity and trade. If more people began to leave agriculture, there are indications that Athens had problems keeping them employed. Even if they found work, there are indications that many were not fully benefiting from Athens' economy.

Island republic of Rhodes

The economy ofRhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

throughout the Ancient period was largely based on shipping (owing to its geographical position near to Asia Minor), it had one of the finest harbours in the Mediterranean and built up a booming economy based upon trade throughout this area, even into Roman times, until the Romans took a prize possession of Rhodes (Delos) and turned it into a free port, thus taking most of their trade - from this point onwards, the Rhodian economy shrivelled. In its prime, Rhodes was however, due to its status as a prize port, a frequent target of piracy and for this reason the Rhodian Government of the time set up a swift and efficient fleet of fast pirate chasing vessels to combat this.

Hellenistic Age

TheHellenistic Age

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 31 ...

was a major turning point both in Greek economic history and Roman economic history, it opened the way for trade with the East, new agricultural techniques were developed and the spread of a relatively uniform currency throughout the near East began.

Macedonia

The Ancient Greek state of Macedonia rose to prominence in the Greek mainland with the reign ofPhilip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

.

Alexander and the successors

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, hoping to strike revenge at the Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, wikt:𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎶, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an History of Iran#Classical antiquity, ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Bas ...

for their past attacks in Greece drove a path Eastwards across the Persian Empire, eventually defeating it and opening the way for trade with India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and other civilizations. This was accompanied by a huge expansion in maritime trade, these trade routes with the Far East were later solidified by the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

. One of the outcomes was the expenditure of bullion that had been hoarded for two centuries by the successors of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

in the efforts to conquer additional territories, create civic foundations, and expand governmental services; L. Sprague deCamp posits this created a period of substantial inflation affecting the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East for several decades.

The economy of the Hellenistic world

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

, however, continued to be overwhelmingly agricultural. Colonial settlement was urban in character in Seleucid Asia, but predominantly rural in Ptolemaic Egypt. Traditional patterns of land tenure predominated in Asia, where large tracts of royal land were worked by peasants tied to it. Much of this land was assigned to prominent individuals, to temple estates, or to cities. The economy of the numerous Seleucid cities, however, followed the Greek model, with land owned by citizens who worked it with the help of slave labor. In Egypt, urban settlements were rare. Outside of the three cities of Naucratis

Naucratis or Naukratis (Ancient Greek: , "Naval Command"; Egyptian: , , , Coptic: ) was a city and trading-post in ancient Egypt, located on the Canopic (western-most) branch of the Nile river, south-east of the Mediterranean sea and the city o ...

, Ptolemais, and Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, all land was theoretically owned by the king, divided into districts ( nomes), and administered by both traditional civic officials— nomarch

A nomarch ( grc, νομάρχης, egy, ḥrj tp ꜥꜣ Great Chief) was a provincial governor in ancient Egypt; the country was divided into 42 provinces, called nomes (singular , plural ). A nomarch was the government official responsib ...

, royal scribe, komarch —and by newly created financial officers — the dioiketes in the capital, and the oikonomos and his underlings in the nome. In addition, military officials — strategos

''Strategos'', plural ''strategoi'', Linguistic Latinisation, Latinized ''strategus'', ( el, στρατηγός, pl. στρατηγοί; Doric Greek: στραταγός, ''stratagos''; meaning "army leader") is used in Greek language, Greek to ...

, hipparchos

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

, and hegemon — oversaw the nomes. Royal land was also assigned to individuals, to temple estates, and especially to small-holder soldiers ( klerouchoi, later called katoikoi) who initially held the land in return for military service, but whose tenure eventually became permanent and hereditary. All land seems to have been worked by native peasants attached to it, chattel slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

being relatively rare in Ptolemaic Egypt. Ptolemaic policy was to increase agricultural production, and innovations in farming were largely the result of royal patronage. We are particularly well informed by the mid-third-century archive of Zenon about large-scale reclamation in the Fayyûm, where new crops and techniques were introduced. But most innovations, in both Egypt and Asia, were directed toward luxury items and, with the exception of new strains of wheat, had little effect on traditional agriculture. In Seleucid Asia the major challenge for agriculture was to feed the numerous new cities, in Egypt to feed the metropolis of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

and to supply the grain used in Ptolemaic diplomacy. In the Greek homeland, established forms of agriculture continued. In most areas, free citizens farmed with the help of a slave or two, while other traditional forms of dependent labor also persisted— helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ex ...

in Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

, serfs in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

. Changes did occur in the pattern of land tenure, with land being accumulated by the wealthy at the expense of marginal farmers.

Roman Era Greek world

The Mainland Greece gave way to WesternAsia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

as the economic and cultural centers of de ranging fame owing to the library and its significance in relation to Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

himself.

Pergamum was another famous city in the Roman province of Asia

The Asia ( grc, Ἀσία) was a Roman province covering most of western Anatolia, which was created following the Roman Republic's annexation of the Attalid Kingdom in 133 BC. After the establishment of the Roman Empire by Augustus, it was the ...

(today's Western Asia Minor) would become one of the most prosperous and famous cities in Asia Minor, noted for its architectural monuments, its fine library, and its schools. Ephesus too, another large Greek city in the same geographical area, became a major source of trade and competed with the other metropolis' of the region for the title of 'First city of Asia'.

Byzantine Economy

The Byzantine economy was the economy of theByzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

which lasted from Constantine's foundation of Nova Roma (Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

) as the capital of a Hellenized, truly 'Graeco-Roman' Empire in 330 to 1453. Throughout its history it employed vast numbers of people in huge industries, particularly in the Capital and Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

(the second city of the empire), in all manner of trades, such as the silk industry.

Early

The early Byzantine economy describes the economy of Roman Empire following the changing of its capital from Rome itself to the newly founded city of Constantinople (or ''Nova Roma'') by the EmperorConstantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

. It was essentially a continuation of the old Roman economy but with a shift in trade flow towards the newly burgeoning Greek city on the Bosphorus rather than Rome itself.

Middle

During the 12th and 13th centuries, the Byzantines were forced to make a few trade concessions to their commercial rivals, the Venetians. Attempts by John Komnenus to revert these trade agreements led to Venetian naval action and the Byzantines forced to reinstate the trade agreements that were favorable to the Venetians.Later

After Constantinople was sacked in 1204 the city continued to bring in trade albeit with fewer gains for Byzantium. The trouble the Byzantines had was that they needed the Italian fleet to assist them in wars where troops and ships were few. The Byzantines attempted to prevent the Venetians from achieving complete economic supremacy by aiding their opponents in Milan and Genoa.Ottoman Greece

During the period of Ottoman rule, Greeks in both the Western coast of Asia Minor as well as Greece proper played an important role in trade, especially maritime (of which the Ottomans had little experience). Centers of trade includedConstantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

as well as Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

. The Ottoman Empire maintained trade routes with the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

through the old silk road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

as well as throughout the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

. Greeks were active in other areas of the economy as well, such as owning coffee shops and other businesses in Constantinople. Following the Greek war of Independence however, Greeks were deemed to be untrustworthy by the Ottomans and their privileged economic status was eventually supplanted by that of the Armenians. Still, in the early part of the 20th century Greeks owned 45% of the capital in the Ottoman Empire despite being a minority.Issawi, Charles, ''The Economic History of the Middle East and North Africa'', Columbia University Press 1984 Agricultural development however, remained stunted until the reforms that followed the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

.

Modern Greece

Modern Greece

The history of modern Greece covers the history of Greece from the recognition by the Great Powers — Britain, France and Russia — of its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1828 to the present day.

Background

The Byzantine Empire had ...

began its history as a nation state in 1829 and was largely an undeveloped economic area mostly based around agriculture. It has since developed into a modernised, developed nation.

19th century

Greece entered its period of new-won independence in a somewhat different state than Serbia, which shared many of the post-independence economic problems such as land and land reform. In 1833, the Greeks took control of a countryside devastated by war, depopulated in places and hampered by primitive agriculture and marginal soils. Just as in Serbia, which secured its autonomy from the Ottoman Empire at around the same time, communications were bad, presenting obstacles for any wider foreign commerce. Even by the late 19th century agricultural development had not advanced as significantly as had been intended as William Moffet, the US Consul in Athens explained: Greece had a substantial wealthy commercial class of rural notables and island shipowners, and access to of land expropriated from Muslim owners who had been driven off during the War of Independence.Land reform

Land reform represented the first real test for the new Greek kingdom. The new Greek government deliberately adopted land reforms intended to create a class of free peasants. The ''"Law for the Dotation of Greek Families"'' of 1835 extended 2,000drachma

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fro ...

s credit to every family, to be used to buy a farm at auction under a low-cost loan plan. The country was full of displaced refugees and empty Turkish estates. By a series of land reforms over several decades, the government distributed this confiscated land among veterans and the poor, so that by 1870 most Greek peasant families owned about . These farms were too small for prosperity but the land reform signaled the goal of a society in which Greeks were equals and could support themselves, instead of working for hire on the estates of the rich. The class basis of rivalry between Greek factions was thereby reduced.

20th century

Industry

During the 19th century slowly developing industrial activity (including heavy industry like shipbuilding) was mainly concentrated inErmoupolis

Ermoupoli ( el, Ερμούπολη), also known by the formal older name Ermoupolis or Hermoupolis ( el, < "Town of "), is a to ...

and Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saronic ...

.Anastasopoulos, G., ''Istoria tis Ellinikis Viomichanias (History of Greek Industry) 1840-1940'', Elliniki Ekdotiki Etairia, Athens 1946Skartsis, L.S., ''Greek Vehicle & Machine Manufacturers 1800 to present: A Pictorial History'', Marathon 2012(eBook) The series of wars between 1912 and 1922 provided a catalyst for Greek industry, with a number of industries such as textiles; ammunition and boot-making springing up to supply the military. After the wars most of these industries were converted to civilian uses.

Greek refugees

Greek refugees is a collective term used to refer to the more than one million Greek Orthodox natives of Asia Minor, Thrace and the Black Sea areas who fled during the Greek genocide (1914-1923) and Greece's later defeat in the Greco-Turkish War ...

from Asia Minor, the most famous of which is Aristotle Onassis

Aristotle Socrates Onassis (, ; el, Αριστοτέλης Ωνάσης, Aristotélis Onásis, ; 20 January 1906 – 15 March 1975), was a Greek-Argentinian shipping magnate who amassed the world's largest privately-owned shipping fleet and wa ...

who hailed from Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

(modern Izmir) also had a tremendous impact on the evolution of Greek industry and banking. Greeks held 45% of the capital in the Ottoman Empire before 1914, and many of the refugees expelled from Turkey had funds and skills which they quickly put to use in Greece.

These refugees from Asia Minor also led to rapid growth of urban areas in Greece, as the vast majority of them settled in urban centers such as Athens and Thessaloniki. The 1920 census reported that 36.3% of Greeks lived in urban or semi-urban areas, while the 1928 census reported that 45.6% of Greeks lived in urban or semi-urban areas. It has been argued by many Greek economists that these refugees kept Greek industry competitive during the 1920s, as the surplus of labor kept real wages very low. Although this thesis makes economic sense, it is sheer speculation as there is no reliable data on wages and prices in Greece during this period.Freris, A. F., ''The Greek Economy in the Twentieth Century'', St. Martin's Press 1986

Greek industry went into decline slightly before the country joined the EC, and this trend continued. Although worker productivity rose significantly in Greece, labor costs increased too fast for the Greek manufacturing industry to remain competitive in Europe. There was also very little modernization in Greek industries due to a lack of financing.Elisabeth Oltheten, George Pinteras, and Theodore Sougiannis, "Greece in the European Union: policy lessons from two decades of membership", ''The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance'' Winter 2003

Dichotomization of the drachma

Budgetary problems caused the Greek government to dichotomization of the drachma. Unable to secure any more loans from abroad to finance the war with Turkey, in 1922 Finance MinisterPetros Protopapadakis

Petros Protopapadakis ( el, Πέτρος Πρωτοπαπαδάκης; 1854–1922) was a Greek politician and Prime Minister of Greece in May–September 1922.

Life and work

Born in 1854 in Apeiranthos, Naxos, Protopapadakis studied mathemati ...

declared that each drachma was essentially to be cut in half. Half of the value of the drachma would be kept by the owner, and the other half would be surrendered by the government in exchange for a 20-year 6.5% loan. World War II led to these loans not being repaid, but even if the war had not occurred it is doubtful that the Greek government would have been able to repay such enormous debts to its own populace. This strategy led to large revenues for the Greek state, and inflation effects were minimal. government's inability to pay back loans incurred from the decade of war and the resettlement of the refugees. Deflation occurred after this dichotomization of the drachma, as well as a rise in interest rates. These policies had the effect of causing much of the populace to lose faith in their government, and investment decreased as people began to stop holding their assets in cash which had become unstable, and began holding real goods.

Great Depression

As the reverberations of the Great Depression hit Greece in 1932, theBank of Greece

The Bank of Greece ( el, Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος , ΤτΕ) is the central bank of Greece. Its headquarters is located in Athens on Panepistimiou Street, but it also has several branches across the country. It was founded in 192 ...

tried to adopt deflationary policies to stave off the crises that were going on in other countries, but these largely failed. For a brief period, the drachma was pegged to the US dollar, but this was unsustainable given the country's large trade deficit and the only long-term effects of this were Greece's foreign exchange reserves being almost totally wiped out in 1932. Remittances from abroad declined sharply and the value of the drachma began to plummet from 77 drachmas to the dollar in March 1931 to 111 drachmas to the dollar in April 1931. This was especially harmful to Greece as the country relied on imports from the UK, France and the Middle East for many necessities. Greece went off the gold standard in April 1932 and declared a moratorium on all interest payments. The country also adopted protectionist policies such as import quotas, which a number of European countries did during the time period.

Protectionist policies coupled with a weak drachma, stifling imports, allowed the Greek industry to expand during the Great Depression. In 1939 Greek Industrial output was 179% that of 1928. These industries were for the most part “built on sand” as one report of the Bank of Greece put it, as without massive protection they would not have been able to survive. Despite the global depression, Greece managed to suffer comparatively little, averaging an average growth rate of 3.5% from 1932-1939. The dictatorial regime of Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; el, Ιωάννης Μεταξάς; 12th April 187129th January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for t ...

took over the Greek government in 1936, and economic growth was strong in the years leading up to the Second World War.

Shipping

The one industry in which Greece had major success was the shipping industry. Greece's geography has made the country a major player in maritime affairs from antiquity, and Greece has a strong modern tradition dating from theTreaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca ( tr, Küçük Kaynarca Antlaşması; russian: Кючук-Кайнарджийский мир), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on 21 July 1774, in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kayna ...

in 1774 which allowed Greek ships to escape Ottoman domination by registering under the Russian flag. The treaty prompted a number of Greek commercial houses to be set up across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

, and after independence, Greece's shipping industry was one of the few bright spots in the modern Greek economy

The economy of Greece is the 53rd largest in the world, with a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of $222.008 billion per annum. In terms of purchasing power parity, Greece is the world's 54th largest economy, at $387.801 billion per annum ...

during the 19th century. After both world wars the Greek shipping industry was hit hard by the decline in world trade, but both times it revived quickly. The Greek government aided the revival of the Greek shipping industry with insurance promises following the Second World War. Tycoons such as Aristotle Onassis also aided in strengthening the Greek merchant fleet, and shipping has remained one of the few sectors in which Greece still excels. Today, the Greek merchant marine comes third globally both in the number of ships owned and in tonnage, and at times in the 90s Greece was first. Greece is fifth in terms of registration, the reason for this is a number of Greek captains register their ships under the Cypriot

Cypriot (in older sources often "Cypriote") refers to someone or something of, from, or related to the country of Cyprus.

* Cypriot people, or of Cypriot descent; this includes:

**Armenian Cypriots

**Greek Cypriots

**Maronite Cypriots

**Turkish C ...

flag, which is easy due to linguistic and cultural commonalities, and significantly where there are lower taxes. In terms of registration, Cyprus has the third largest merchant fleet, and the majority of these ships are actually owned by Greeks, but sailing under the Cypriot flag for tax purposes.

Tourism

It was during the 60s and 70s that tourism, which now accounts for 15% of Greece'sGDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is often ...

, began to become a major earner of foreign exchange. This was initially opposed by many in the Greek government, as it was seen as a very unstable source of income in the event of any political shocks. It was also opposed by many conservatives and by the Church as bad for the country's morals. Despite concerns, tourism grew significantly in Greece and was encouraged by successive governments as it was a very easy source of badly needed foreign exchange revenues.

Agriculture

The resolution of the Greco-Turkish War and theTreaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

led to a population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

, which also had massive ramifications on the agricultural sector in Greece. The tsifliks were abolished, and Greek refugees from Asia Minor settled on these abandoned and partitioned estates. In 1920 only 4% of land holdings were of sizes more than , and only .3% of these were in large estates of more than . This pattern of small scale farm ownership has continued to the present day, with the small number of larger farms declining slightly.

Greece differed greatly from any other country in the EC at the time of its admission as agriculture, although in decline, was a much larger sector of the economy than in any other EC member. In 1981 Greek agriculture made up 17% of GDP and 30% of employment, in comparison to 5% of GDP and less than 10% of employment in EU countries excluding Ireland and Italy. Greece managed to implement the reforms according to the Common Agricultural Policy

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is the agricultural policy of the European Union. It implements a system of agricultural subsidies and other programmes. It was introduced in 1962 and has since then undergone several changes to reduce the ...

(CAP) ahead of schedule, with prices generally rising to meet those in the rest of the EC. Previously Greece had heavily subsidized agriculture, and moving to the CAP meant that Greece moved from subsidies to price supports, so the consumer rather than the taxpayer would bear the burden of supporting farmers. Due to the CAP being formulated with other countries in mind, CAP subsidies had the effect of moving production away from products in which Greece had a comparative advantage, which hurt the country's trade balance. While farm incomes rose slightly after Greece's entry into the EC, this has not stopped the general trend of an ever decreasing agricultural sector which is in line with other European countries.

Post-World War II

Greece suffered comparatively much more than most Western European countries during the Second World War due to a number of factors. Heavy resistance led to immense German reprisals against civilians. Greece was also dependent on food imports, and a British naval blockade coupled with transfers of agricultural produce to Germany led to famine. It is estimated that the Greek population declined by 7% during the Second World War. Greece experiencedhyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

during the war. In 1943, prices were 34,864% higher compared to those of 1940; in 1944, prices were 163,910,000,000% higher compared to the 1940 prices. The Greek hyperinflation is the fifth worst in economic history, after Hungary's following World War II, Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

’s in the late 2000s, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

’s in the middle 1990s, and Germany's following World War I. This was compounded by the country's disastrous civil war from 1944-1949.

Greek economy was in an extremely poor state in 1950 (after the end of the Civil War), with its relative position dramatically affected. In that year Greece had a per capita GDP of $1,951, which was well below that of countries like Portugal ($2,132), Poland ($2,480), and even Mexico ($2,085). Greece's per capita GDP was comparable to that of countries like Bulgaria ($1,651), Japan ($1,873), or Morocco ($1,611). Greece's per-capita GDP grew quickly. Greece's growth averaged 7% between 1950 and 1973, a rate second only to Japan's during the same period. In 1950 Greece was ranked 28th in the world for per capita GDP, while in 1970 it was ranked 20th.

Late 20th century

During the 80s, despite membership in the EC, Greece suffered from poor macroeconomic performance due to expansionary fiscal policies that led to a tripling of thedebt-to-GDP ratio

In economics, the debt-to-GDP ratio is the ratio between a country's government debt (measured in units of currency) and its gross domestic product (GDP) (measured in units of currency per year). While it is a "ratio", it is technically measured i ...

, which went from the modest figure of 34.5% in 1981 to the triple digits by the 90s. The second oil shock after the Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

hurt Greece, and the 80s were racked by high inflation as politicians pursued populist policies. The average rate of inflation in Greece during the 80s was 19%, which was three times the EU average. The Greek budget deficit also rose very substantially during the 80s, peaking at 9% in 1985. In the late 80s Greece implemented stabilization programs, cutting inflation from 25% in 1985 to 16% in 1987.

The debt accumulated in the 80s was a large problem for the Greek government, and by 1991 interest payments on the public debt reached almost 12% of GDP. When the Maastricht Treaty was signed in 1991, Greece was very far from meeting the convergence criteria. For example, the inflation rate of Greece was 19.8%, while the EU average was 4.07% and the government's deficit was 11.5% of GDP, while the EU average was 3.64%. Nonetheless, Greece was able to dramatically improve its finances during the 1990s, with both inflation and budget deficit falling below 3% by 1999, and the government concealed economic problems. Thus, it met the criteria for entry into Eurozone (including the budget deficit criterion even after its recent revision calculated with the method in force at the time).

Debt crisis (2010-2018)

Greek economy had fared well for much of the 20th century, with high growth rates and low public debt. As a result of internal and external factors (mainly, the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008), the country entered a prolonged recession in 2008 and, after a significant rise in its borrowing costs, by April 2010 the government realized that it would need a rescue package. Greece had the biggest sovereign debt restructuring in history in 2012. In April 2014, Greece returned to the global bond market as it successfully sold €3 billion worth of five-year government bonds at a yield of 4.95%. Greece had real GDP growth of 0.7% in 2014 after 5 years of decline. After a third bailout in 2015 (following the election of the leftist SYRIZA Party), Greece bailouts ended successfully (as declared) on August 20, 2018.

Greek economy had fared well for much of the 20th century, with high growth rates and low public debt. As a result of internal and external factors (mainly, the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008), the country entered a prolonged recession in 2008 and, after a significant rise in its borrowing costs, by April 2010 the government realized that it would need a rescue package. Greece had the biggest sovereign debt restructuring in history in 2012. In April 2014, Greece returned to the global bond market as it successfully sold €3 billion worth of five-year government bonds at a yield of 4.95%. Greece had real GDP growth of 0.7% in 2014 after 5 years of decline. After a third bailout in 2015 (following the election of the leftist SYRIZA Party), Greece bailouts ended successfully (as declared) on August 20, 2018.

See also

*Economy of Europe

The economy of Europe comprises about 748 million people in 50 countries. The formation of the European Union (EU) and in 1999 the introduction of a unified currency, the Euro, brought participating European countries closer through the ...

*Greek phoenix

The ''phoenix'' ( el, φοίνιξ, ''foinix'') was the first currency of the modern Greek state. It was introduced in 1828 by Governor Count Ioannis Kapodistrias and was subdivided into 100 ''lepta''. The name was that of the mythical phoenix ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Economic History Of Greece And The Greek World Economic history of Greece