Executive Order 9066 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential

In 1943 and 1944, Roosevelt did not release those incarcerated in the camps despite the urgings of Attorney General Francis Biddle and Secretary of Interior Harold L. Ickes. Ickes blamed the president's failure to act on his need to win California in a potentially close election. In December 1944, Roosevelt suspended the Executive Order after the

In 1943 and 1944, Roosevelt did not release those incarcerated in the camps despite the urgings of Attorney General Francis Biddle and Secretary of Interior Harold L. Ickes. Ickes blamed the president's failure to act on his need to win California in a potentially close election. In December 1944, Roosevelt suspended the Executive Order after the

Text of Executive Order No. 9066

Digital Copy of Signed Executive Order No. 9066

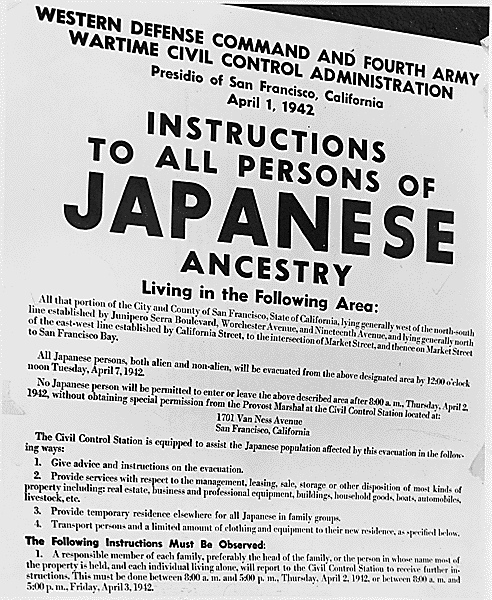

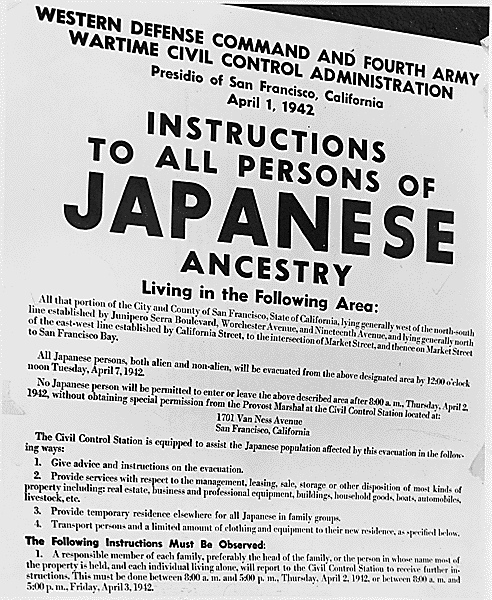

Instructional poster for Los Angeles

German American Internment Coalition

FOITimes a resource for European American Internment of World War 2

{{Authority control 9066 History of racial segregation in the United States Legal history of the United States 1942 in American law Internment of Japanese Americans Civil detention in the United States Political repression in the United States Internment of German Americans Alien and Sedition Acts

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of the ...

signed and issued during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

on February 19, 1942. "This order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to 'relocation centers' further inland—resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans

are Americans of Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian Americans, Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 United States census, 2000 census, they have declined in ...

." Two-thirds of the 125,000 people displaced were U.S. citizens.

Notably, far more Americans of Asian descent were forcibly interned than Americans of European descent, both in total and as a share of their relative populations. German and Italian Americans who were sent to internment camps during the war were sent under the provisions of Presidential Proclamation 2526 and the Alien Enemy Act, part of the Alien and Sedition Act of 1798.

Transcript of Executive Order 9066

The text of Executive Order 9066 was as follows:Background to the Order

Originating from a proclamation that was signed on the day of the Pearl Harbor attack, December 7, 1941, Executive Order 9066 was enacted by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to strictly regulate the actions of Japanese Americans in the United States. At this point, Japanese Americans were not allowed to apply for citizenship in the United States, despite having lived in the United States for generations. This proclamation declared all Japanese American adults as the "alien enemy," resulting in strict travel bans and mass xenophobia toward Asian Americans. Tensions rose in the United States, ultimately causing President Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The Order was consistent with Roosevelt's long-time racial views toward Japanese Americans. During the 1920s, for example, he had written articles in the '' Macon Telegraph'' opposing white-Japanese intermarriage for fostering "the mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood" and praising California's ban on land ownership by the first-generation Japanese. In 1936, while president he privately wrote that, in regard to contacts between Japanese sailors and the local Japanese American population in the event of war, "every Japanese citizen or non-citizen on the Island of Oahu who meets these Japanese ships or has any connection with their officers or men should be secretly but definitely identified and his or her name placed on a special list of those who would be the first to be placed in a concentration camp." In addition, during the crucial period after Pearl Harbor the president had failed to speak out for the rights of Japanese Americans despite the urgings of advisors such as John Franklin Carter. During the same period, Roosevelt rejected the recommendations of Attorney General Francis Biddle and other top advisors, who opposed the incarceration of Japanese Americans.Exclusion under the Order

The text of Roosevelt's order did not use the terms "Japanese" or "Japanese Americans," instead giving officials broad power to exclude "any or all persons" from a designated area. (The lack of a specific mention of Japanese or Japanese Americans also characterized Public Law 77-503, which Roosevelt signed on March 21, 1942, to enforce the order.) Nevertheless, EO 9066 was intended to be applied almost solely to persons of Japanese descent. Notably, in a 1943 letter, Attorney General Francis Biddle reminded Roosevelt that "You signed the original Executive Order permitting the exclusions so the Army could handle the Japs. It was never intended to apply to Italians and Germans." Public Law 77-50An act to provide a penalty for violation of restriction or orders with respect to persons entering, remaining in, leaving, or committing any act in military areas or zones. . was approved (after only an hour of discussion in the Senate and thirty minutes in the House) in order to provide for the enforcement of the executive order. Authored by War Department official Karl Bendetsen—who would later be promoted to Director of the Wartime Civilian Control Administration and oversee the incarceration of Japanese Americans—the law made violations of military orders a misdemeanor punishable by up to $5,000 in fines and one year in prison. Using a broad interpretation of EO 9066, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt issued orders declaring certain areas of the western United States as zones of exclusion under the Executive Order. In contrast to EO 9066, the text of these orders specified "all people of Japanese ancestry." As a result, approximately 112,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were evicted from the West Coast of the continental United States and held in American relocation camps and other confinement sites across the country. Roosevelt hoped to establish concentration camps for Japanese Americans in Hawaii even after he signed Executive Order 9066. On February 26, 1942, he informed Secretary of the Navy Knox that he had "long felt most of the Japanese should be removed from Oahu to one of the other islands." Nevertheless, the tremendous cost, including the diversion of ships from the front lines, as well as the quiet resistance of the local military commander General Delos Emmons, made this proposal impractical, resulting in Japanese Americans in Hawaii never being incarcerated ''en masse''. Although the Japanese-American population in Hawaii was nearly 40% of the population of the territory and Hawaii would have been first in line for a Japanese attack, only a few thousand people were temporarily detained there. This fact supported the government's eventual conclusion that the mass removal of ethnic Japanese from the West Coast was motivated by reasons other than "military necessity." Japanese Americans and other Asians in the U.S. had suffered for decades from prejudice and racially motivated fears. Racially discriminatory laws prevented Asian Americans from owning land, voting, testifying against whites in court, and set up other restrictions. Additionally, theFBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

, Office of Naval Intelligence

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) is the military intelligence agency of the United States Navy. Established in 1882 primarily to advance the Navy's modernization efforts, it is the oldest member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and serv ...

and Military Intelligence Division had been conducting surveillance on Japanese-American communities in Hawaii and the continental U.S. from the early 1930s. In early 1941, President Roosevelt secretly commissioned a study to assess the possibility that Japanese Americans would pose a threat to U.S. security. The report, submitted one month before the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, predicted that in the event of war, "There will be no armed uprising of Japanese" in the United States. "For the most part," the Munson Report said, "the local Japanese are loyal to the United States or, at worst, hope that by remaining quiet they can avoid concentration camps or irresponsible mobs." A second investigation started in 1940, written by Naval Intelligence officer Kenneth Ringle and submitted in January 1942, likewise found no evidence of fifth column

A fifth column is a group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. The activities of a fifth column can be overt or clandestine. Forces gathered in secret can mobilize ...

activity and urged against mass incarceration. Both were ignored by military and political leaders.

Over two-thirds of the people of Japanese ethnicity who were incarcerated were American citizens; many of the rest had lived in the country between 20 and 40 years. As a result, most Japanese Americans, particularly the first generation born in the United States (the ''Nisei

is a Japanese language, Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the nikkeijin, ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants, or . The , or Second generation imm ...

''), identified as loyal to the United States of America. In addition, no Japanese-American citizen or Japanese national residing in the United States was ever found guilty of sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, government, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, demoralization (warfare), demoralization, destabilization, divide and rule, division, social disruption, disrupti ...

or espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

.

There were 10 of these internment camps across the United States, euphemistically called "relocation centers". There were two in Arkansas, two in Arizona, two in California, one in Idaho, one in Utah, one in Wyoming, and one in Colorado.

World War II camps under the Order

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson was responsible for assisting relocated people with transport, food, shelter, and other accommodations and delegated Colonel Karl Bendetsen to administer the removal of West Coast Japanese. Over the spring of 1942, General John L. DeWitt issuedWestern Defense Command

Western Defense Command (WDC) was established on 17 March 1941 as the command formation of the United States Army responsible for coordinating the defense of the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast region of the United States during Wo ...

orders for Japanese Americans to present themselves for removal. The "evacuees" were taken first to temporary assembly centers, requisitioned fairgrounds and horse racing tracks where living quarters were often converted livestock stalls. As construction on the more permanent and isolated War Relocation Authority camps was completed, the population was transferred by truck or train. These accommodations consisted of tar paper-walled frame buildings in parts of the country with bitter winters and often hot summers. The camps were guarded by armed soldiers and fenced with barbed wire (security measures not shown in published photographs of the camps). Camps held up to 18,000 people, and were small cities, with medical care, food, and education provided by the government. Adults were offered "camp jobs" with wages of $12 to $19 per month, and many camp services such as medical care and education were provided by the camp inmates themselves.

Not only was there limited room for living but, "Living in cramped barracks with minimal privacy and inadequate facilities. The camp's location in Utah's desert meant extreme temperatures and harsh weather, making daily life even more challenging." Based on the evidence listed, it is proven that these camps held poor living conditions for those relocated. On top of that children had to undergo education in these barracks as well as buildings for religion, all of these conditions add to the unpleasant way of life.

Opposition

According to a poll conducted in March 1942, majorities of Americans believed that the internment of Japanese Americans, regardless of citizenship, was appropriate. Because of the widespread support for the order, public opposition to it was minimal. Still, there were efforts made by prominent individuals to either stop or mitigate the effects of the order. Norman Thomas, chairman of theSocialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of America ...

, was a vocal critic of the order and worked to defend the rights of Japanese Americans. during the period of internment, he remained in contact with people in the camps, as well as various people and organizations involved in preserving the civil rights of Japanese Americans. In July 1942, Thomas published ''Democracy and Japanese Americans'', discussing the conditions inside the camps and the legality of the order. In late 1943, Thomas stated of the Japanese internment that "Congress and the President have created a dangerous precedent by adopting wholesale the totalitarian theories of justice by discrimination on the basis of racial affiliation."

Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

, who publicly stood behind the president, expressed concern in private about the necessity of the camps. She generally advocated for a more moderate approach to interring spies, and publicly stated the laws of the United States should apply equally to all citizens, regardless of race or nationality.

Termination, apology, and redress

In 1943 and 1944, Roosevelt did not release those incarcerated in the camps despite the urgings of Attorney General Francis Biddle and Secretary of Interior Harold L. Ickes. Ickes blamed the president's failure to act on his need to win California in a potentially close election. In December 1944, Roosevelt suspended the Executive Order after the

In 1943 and 1944, Roosevelt did not release those incarcerated in the camps despite the urgings of Attorney General Francis Biddle and Secretary of Interior Harold L. Ickes. Ickes blamed the president's failure to act on his need to win California in a potentially close election. In December 1944, Roosevelt suspended the Executive Order after the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

decision '' Ex parte Endo''. Detainees were released, often to resettlement facilities and temporary housing, and the camps were shut down by 1946.

On February 19, 1976, President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

signed a proclamation formally terminating Executive Order 9066 and apologizing for the internment, stated: "We now know what we should have known then—not only was that evacuation wrong but Japanese Americans were and are loyal Americans. On the battlefield and at home the names of Japanese Americans have been and continue to be written in history for the sacrifices and the contributions they have made to the well-being and to the security of this, our common Nation."

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

signed legislation to create the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). The CWRIC was appointed to conduct an official governmental study of Executive Order 9066, related wartime orders, and their effects on Japanese Americans in the West and Alaska Natives

Alaska Natives (also known as Native Alaskans, Alaskan Indians, or Indigenous Alaskans) are the Indigenous peoples of Alaska that encompass a diverse arena of cultural and linguistic groups, including the Iñupiat, Yupik, Aleut, Eyak, Tli ...

in the Pribilof Islands.

In December 1982, the CWRIC issued its findings in ''Personal Justice Denied'', concluding that the incarceration of Japanese Americans had not been justified by military necessity. The report determined that the decision to incarcerate was based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership". The Commission recommended legislative remedies consisting of an official Government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

apology and redress payments of $20,000 to each of the survivors; a public education fund was set up to help ensure that this would not happen again ().

On August 10, 1988, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (, title I, August 10, 1988, , et seq.) is a United States federal law that granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been wrongly interned by the United States government during World War II and to "di ...

, based on the CWRIC recommendations, was signed into law by Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

. On November 21, 1989, George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

signed an appropriation bill authorizing payments to be paid out between 1990 and 1998. In 1990, surviving internees began to receive individual redress payments and a letter of apology. This bill applied to the Japanese Americans and to members of the Aleut people inhabiting the strategic Aleutian islands

The Aleutian Islands ( ; ; , "land of the Aleuts"; possibly from the Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', or "island")—also called the Aleut Islands, Aleutic Islands, or, before Alaska Purchase, 1867, the Catherine Archipelago—are a chain ...

in Alaska who had also been relocated.

Life after the camps

In the years after the war, the interned Japanese Americans had to rebuild their lives after having suffered heavy personal losses. United States citizens and long-time residents who had been incarcerated lost their liberties. Many also lost their homes, businesses, property, and savings. Individuals born in Japan were not allowed to become naturalized US citizens until after the passage of theImmigration and Nationality Act of 1952

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (), also known as the McCarran–Walter Act, codified under Title 8 of the United States Code (), governs immigration to and citizenship in the United States. It came into effect on June 27, 1952. The l ...

, which canceled the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

and reinstated the legality of immigration from Japan into the US.

Many Japanese Americans hoped they would be going back to their homes, but soon realized that all of their possessions that they could carry with them were seized by the government. In place of their homes, the Federal government provided trailers in some areas for returning Japanese Americans. The populous Asian American community prior to the incarceration drastically decreased as many felt there was no life to go back to, choosing to start over somewhere else. With the residual effects of being incarcerated without committing a crime, the Japanese American community experienced strong trauma and continuing racism from their fellow Americans. Though they did receive redress of $20,000 per surviving incarcerate, many Japanese Americans feared increased xenophobia

Xenophobia (from (), 'strange, foreign, or alien', and (), 'fear') is the fear or dislike of anything that is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression that is based on the perception that a conflict exists between an in-gr ...

and a minimizing of the trauma that the Japanese community endured during the WWII incarceration. Managing the wrongs committed to their community, Japanese Americans slowly managed to overcome their community's criminalization and incarceration and came to recognize February 19, the day President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, as a National Day of Remembrance for Americans to reflect on the events that took place.

Court challenges

Korematsu v. United States

After the signing of Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, all Japanese Americans were required to be removed from their homes and moved into military camps as a matter of national security. Fred Korematsu, 23 at the time, was someone who elected not to comply, unlike his parents who left their home and flower nursery behind. Instead, Korematsu had plastic surgery to alter the appearance of his eyes and changed his name to Clyde Sarah, claiming Spanish and Hawaiian heritage. Six months later, on May 30, Korematsu was arrested for violating the order, leading to a trial in a San Francisco Federal Court. His case was presented by the American Civil Liberties Union, which attempted to challenge whether this order was constitutional or not. After losing the case, Korematsu appealed the decision all the way to the Supreme Court, where in a 6–3 decision, the order remained for reason of "military necessity."Hirabayashi v. United States

Included in FDR's order was a curfew starting at 8pm and ended at 6 am for all those of Japanese descent. University of Washington student, Gordon Hirabayashi, refused to abide by the order in an act of civil disobedience, resulting in his arrest. Similar to Korematsu's case, it was appealed and up to the Supreme Court. It was held by the Supreme Court in a unanimous decision that his arrest was constitutional on the basis of military necessity. He was sentenced six months in prison as a result of his civil disobedience.Yasui v. United States

Earning his JD in 1939 from the University of Oregon, Minoru Yasui was the first Japanese American attorney admitted to the state of Oregon's bar. He began working at a consulate in Chicago for the Japanese government, but resigned shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Returning to Oregon, where he was born, he tried to join the US Army but was denied. He was arrested in December 1941 for violating the military curfew, leading to his arrest and freezing of his assets. Looking to test the constitutionality of the curfew, Yasui turned himself into the police station at 11pm, five hours past the curfew. Yasui was found guilty of violating this curfew and was fined $5000 for not being a US citizen, despite being born in Oregon. He served a one-year prison sentence. Yasui appealed his case up to the Supreme Court, where it was held that the curfew was constitutional based on military necessity.Reopening and justice

In 1983, Peter Irons and Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga discovered crucial evidence that allowed for them to petition to reopen the Korematsu case. The evidence was a copy of Lieutenant Commander K.D. Ringle's original report by the US Navy, which had not been destroyed. The report was in response to the question of Japanese loyalty to the US. It was stated in the report that Japanese Americans did not truly pose a threat to the US government, showing that the passage of Executive Order 9066 was entirely based on the false pretense that Japanese Americans were "enemy aliens." This new found evidence was a document that failed to be destroyed by the US government which included government intelligence agencies citing that Japanese Americans posed no military threat. The cases of Korematsu, Hirabayashi, and Yasui were reopened and overturned on the basis of government misconduct on November 10, 1983. In 2010, the state of California passed a bill that would name January 30 Fred Korematsu Day, making this the first day to be named after an Asian American. '' Korematsu v. United States'' was officially overturned in 2018, with JusticeSonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

, describing the case as "gravely wrong the day it was decided."

Legacy

February 19, the anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066, is now the Day of Remembrance, an annual commemoration of the unjust incarceration of the Japanese-American community. In 2017, the Smithsonian launched an exhibit about these events with artwork by Roger Shimomura. It provides context and interprets the treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II. In February 2022, for the 80th anniversary of the signing of the order, supporters lobbied to pass the Amache National Historic Site Act historical designation for the Granada War Relocation Center in Colorado.See also

* Defence Regulation 18B * '' Ex parte Endo'' * Executive Order 9102 *Niihau incident

The Niʻihau incident occurred on December 7–13, 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service pilot crash-landed on the Territory of Hawaii, Hawaiian island of Niihau, Niʻihau after participating in the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Impe ...

* Bob Emmett Fletcher

* Internment of Japanese Canadians

* Japanese American service in World War II

* Fred Korematsu Day

* Manzanar

Manzanar is the site of one of ten American concentration camps, where more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II from March 1942 to November 1945. Although it had over 10,000 inmates at its peak, it was one ...

* George Takei

George Takei ( ; born April20, 1937), born , is an American actor, author and activist known for his role as Hikaru Sulu, helmsman of the USS ''Enterprise'' in the ''Star Trek'' franchise.

Takei was born to Japanese-American parents, with w ...

, Japanese American actor who was interned at one of the camps as a child and wrote a memoir about it titled '' They Called Us Enemy''

* War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was t ...

References

External links

Text of Executive Order No. 9066

Digital Copy of Signed Executive Order No. 9066

Instructional poster for Los Angeles

German American Internment Coalition

FOITimes a resource for European American Internment of World War 2

{{Authority control 9066 History of racial segregation in the United States Legal history of the United States 1942 in American law Internment of Japanese Americans Civil detention in the United States Political repression in the United States Internment of German Americans Alien and Sedition Acts