execution by elephant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Execution by elephant was a method of

Execution by elephant was a method of

Hindu and Muslim rulers in India executed tax evaders, rebels and enemy soldiers alike "under the feet of elephants". The Hindu ''

Hindu and Muslim rulers in India executed tax evaders, rebels and enemy soldiers alike "under the feet of elephants". The Hindu '' The early-19th-century writer Robert Kerr relates how the king of

The early-19th-century writer Robert Kerr relates how the king of

Elephants were widely used across the

Elephants were widely used across the

Execution by elephant was a method of

Execution by elephant was a method of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

in South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, particularly in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, where Asian elephant

The Asian elephant (''Elephas maximus''), also known as the Asiatic elephant, is the only living species of the genus ''Elephas'' and is distributed throughout the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, from India in the west, Nepal in the no ...

s were used to crush, dismember or torture captives in public execution

A public execution is a form of capital punishment which "members of the general public may voluntarily attend." This definition excludes the presence of only a small number of witnesses called upon to assure executive accountability. The purpose ...

s. The animals were trained to kill victims immediately or to torture them slowly over a prolonged period. Most commonly employed by royalty, the elephants were used to signify both the ruler's power of life and death over his subjects and his ability to control wild animals.

The sight of elephants executing captives was recorded in contemporary journals and accounts of life in Asia by European travellers. The practice was eventually suppressed by the European colonial powers that colonised the region in the 18th and 19th centuries. While primarily confined to Asia, the practice was occasionally used by Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and African

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

powers, such as Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 B ...

and Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, particularly to deal with mutinous soldiers.

Cultural aspects

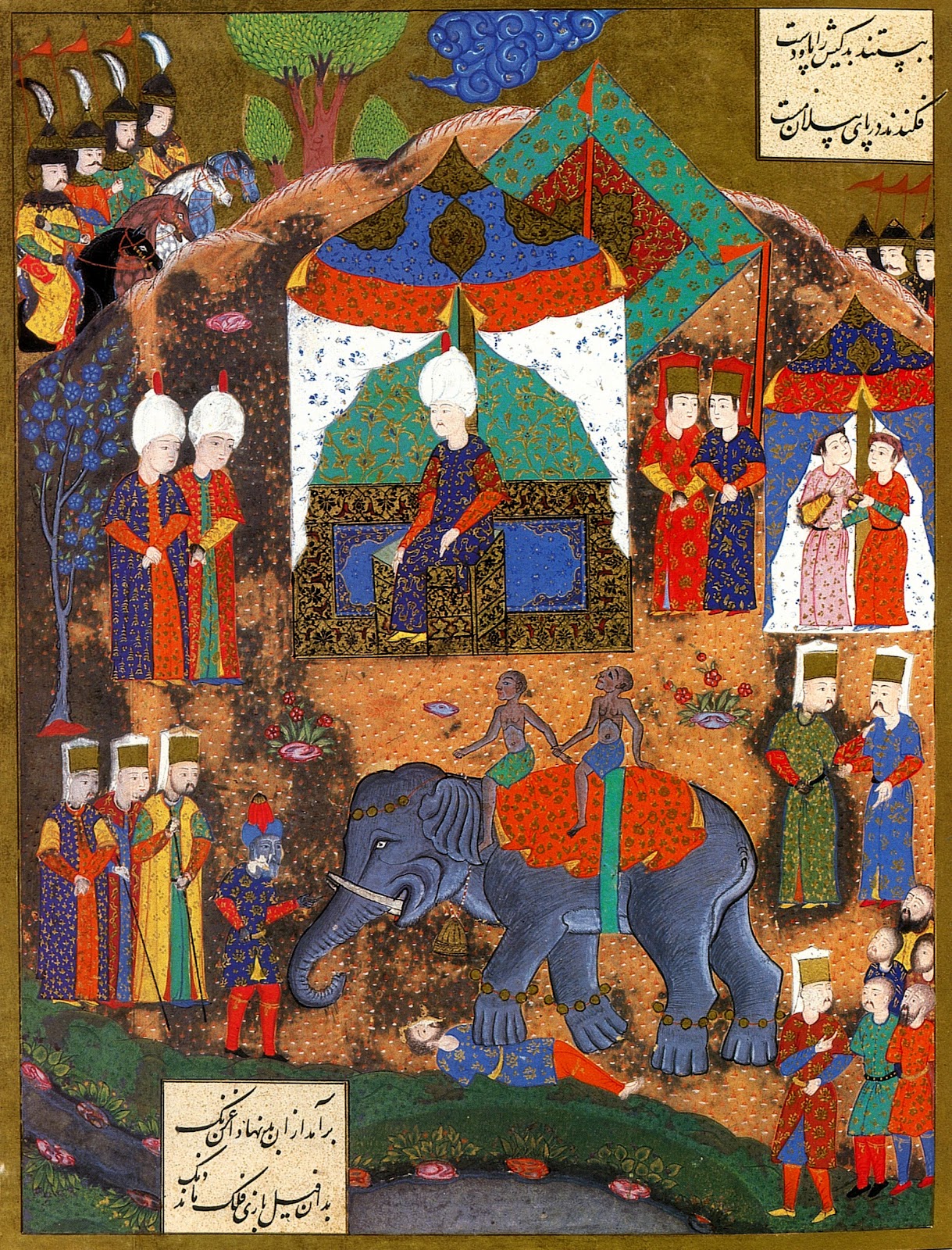

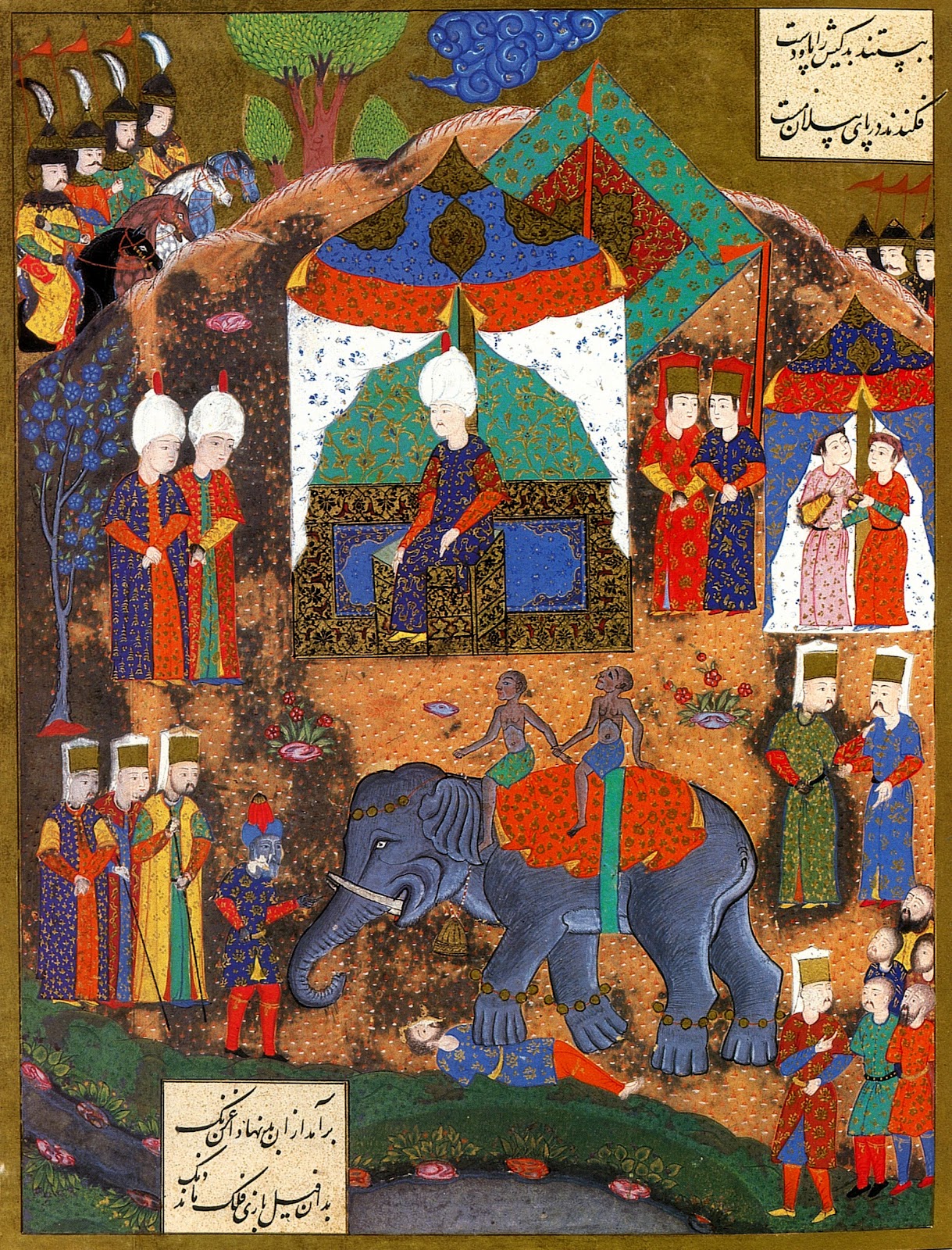

Historically, the elephants were under the constant control of a driver or ''mahout

A mahout is an elephant rider, trainer, or keeper. Mahouts were used since antiquity for both civilian and military use. Traditionally, mahouts came from ethnic groups with generations of elephant keeping experience, with a mahout retaining h ...

'', thus enabling a ruler to grant a last-minute reprieve and display merciful qualities. Several such exercises of mercy

Mercy (Middle English, from Anglo-French ''merci'', from Medieval Latin ''merced-'', ''merces'', from Latin, "price paid, wages", from ''merc-'', ''merxi'' "merchandise") is benevolence, forgiveness, and kindness in a variety of ethical, relig ...

are recorded in various Asian kingdoms. The kings of Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 mi ...

trained their elephants to roll the convicted person "about the ground rather slowly so that he is not badly hurt". The Mughal Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Akbar

Abu'l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar (25 October 1542 – 27 October 1605), popularly known as Akbar the Great ( fa, ), and also as Akbar I (), was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Hum ...

is said to have "used this technique to chastise 'rebels' and then in the end the prisoners, presumably much chastened, were given their lives". On one occasion, Akbar was recorded to have had a man thrown to the elephants to suffer five days of such treatment before pardoning him. Elephants were occasionally used in trial by ordeal

Trial by ordeal was an ancient judicial practice by which the guilt or innocence of the accused was determined by subjecting them to a painful, or at least an unpleasant, usually dangerous experience.

In medieval Europe, like trial by combat, tri ...

in which the condemned prisoner was released if he managed to fend off the elephant.

The use of elephants in such fashion went beyond the common royal power to dispense life and death. Elephants have long been used as symbols of royal authority (and still are in some places, such as Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

, where white elephants are held in reverence). Their use as instruments of state power sent the message that the ruler was able to preside over very powerful creatures who were under total command. The ruler was thus seen as maintaining a moral and spiritual domination over wild beasts, adding to their authority and mystique among subjects.

Geographical scope

Asian powers

Southeast Asia

Elephants were used for execution inBurma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, the Malay Peninsula

The Malay Peninsula (Malay: ''Semenanjung Tanah Melayu'') is a peninsula in Mainland Southeast Asia. The landmass runs approximately north–south, and at its terminus, it is the southernmost point of the Asian continental mainland. The area ...

and Brunei

Brunei ( , ), formally Brunei Darussalam ( ms, Negara Brunei Darussalam, Jawi alphabet, Jawi: , ), is a country located on the north coast of the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. Apart from its South China Sea coast, it is completely sur ...

in the pre-modern period as well as in the kingdom of Champa

Champa (Cham: ꨌꩌꨛꨩ; km, ចាម្ប៉ា; vi, Chiêm Thành or ) were a collection of independent Cham polities that extended across the coast of what is contemporary central and southern Vietnam from approximately the 2nd cen ...

. In Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 mi ...

, elephants were trained to throw the condemned into the air before trampling them to death. There exists an account in the 1560s of men being trampled to death by elephants in Ayutthaya Ayutthaya, Ayudhya, or Ayuthia may refer to:

* Ayutthaya Kingdom, a Thai kingdom that existed from 1350 to 1767

** Ayutthaya Historical Park, the ruins of the old capital city of the Ayutthaya Kingdom

* Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya province (locally ...

due to their unruly behaviour. Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

provides the following account from Siam:

The journal of John Crawfurd

John Crawfurd (13 August 1783 – 11 May 1868) was a Scottish physician, colonial administrator, diplomat, and author who served as the second and last Resident of Singapore.

Early life

He was born on Islay, in Argyll, Scotland, the son of S ...

records another method of execution by elephant in the kingdom of Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exony ...

(modern south Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

), where he served as a British envoy in 1821. Crawfurd recalls an event where "the criminal is tied to a stake, and xcellency's favouriteelephant runs down upon him and crushes him to death."

South Asia

= India

= Hindu and Muslim rulers in India executed tax evaders, rebels and enemy soldiers alike "under the feet of elephants". The Hindu ''

Hindu and Muslim rulers in India executed tax evaders, rebels and enemy soldiers alike "under the feet of elephants". The Hindu ''Manu Smriti

The ''Manusmṛiti'' ( sa, मनुस्मृति), also known as the ''Mānava-Dharmaśāstra'' or Laws of Manu, is one of the many legal texts and constitution among the many ' of Hinduism. In ancient India, the sages often wrote their ...

'' or Laws of Manu, written sometime between 200 BCE and 200 CE, prescribed execution by elephants for a number of offences. If property was stolen, for instance, "the king should have any thieves caught in connection with its disappearance executed by an elephant." For example, in 1305, the sultan of Delhi

The following list of Indian monarchs is one of several lists of incumbents. It includes those said to have ruled a portion of the Indian subcontinent, including Sri Lanka.

The Mahajanapada, earliest Indian rulers are known from epigraphica ...

turned the deaths of Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member of ...

prisoners into public entertainment by having them crushed by elephants.

During the Mughal era, "it was a common mode of execution in those days to have the offender trampled underfoot by an elephant." Captain Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

, writing in 1727, described how the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan

Shihab-ud-Din Muhammad Khurram (5 January 1592 – 22 January 1666), better known by his regnal name Shah Jahan I (; ), was the fifth emperor of the Mughal Empire, reigning from January 1628 until July 1658. Under his emperorship, the Mugha ...

ordered an offending military commander to be carried "to the Elephant Garden, and there to be executed by an Elephant, which is reckoned to be a shameful and terrible Death". The Mughal Emperor

The Mughal emperors ( fa, , Pādishāhān) were the supreme heads of state of the Mughal Empire on the Indian subcontinent, mainly corresponding to the modern countries of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. The Mughal rulers styled t ...

Humayun

Nasir-ud-Din Muhammad ( fa, ) (; 6 March 1508 – 27 January 1556), better known by his regnal name, Humāyūn; (), was the second emperor of the Mughal Empire, who ruled over territory in what is now Eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, Northern ...

ordered the crushing by elephant of an imam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, ser ...

he mistakenly believed to be critical of his reign. Some monarchs also adopted this form of execution for their own entertainment. The emperor Jahangir

Nur-ud-Din Muhammad Salim (30 August 1569 – 28 October 1627), known by his imperial name Jahangir (; ), was the fourth Mughal Emperor, who ruled from 1605 until he died in 1627. He was named after the Indian Sufi saint, Salim Chishti.

Ear ...

, another Mughal emperor, is said to have ordered a huge number of criminals to be crushed for his amusement. The French traveler François Bernier

François Bernier (25 September 162022 September 1688) was a French physician and traveller. He was born in Joué-Etiau in Anjou. He stayed (14 October 165820 February 1670) for around 12 years in India.

His 1684 publication "Nouvel ...

, who witnessed such executions, recorded his dismay at the pleasure that the emperor derived from this cruel punishment. Nor was crushing the only method used by the Mughals' execution elephants; in the Mughal sultanate of Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

, elephants were trained to slice prisoners to pieces "with pointed blades fitted to their tusks".

The Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berbers, Berber Maghrebi people, Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, ...

, visiting Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

in the 1330s, has left the following eyewitness account of this particular type of execution by elephants:

Other Indian polities also carried out executions by elephant. The Maratha

The Marathi people (Marathi: मराठी लोक) or Marathis are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group who are indigenous to Maharashtra in western India. They natively speak Marathi, an Indo-Aryan language. Maharashtra was formed as a M ...

Chatrapati

Chhatrapati is a royal title from Sanskrit language.The word ‘Chhatrapati’ is a Sanskrit language compound word (tatpurusha in Sanskrit) of ''Chatra (umbrella), chhatra'' (''parasol'' or ''umbrella'') and ''pati'' (''master/lord/ruler''). Th ...

Sambhaji

Sambhaji Bhosale (14 May 1657 – 11 March 1689) was the second Chhatrapati of the Maratha Empire, ruling from 1681 to 1689. He was the eldest son of Shivaji, the founder of the Maratha Empire. Sambhaji's rule was largely shaped by the ongoing ...

ordered this form of death for a number of conspirators, including the Maratha official Anaji Datto in the late seventeenth century. Another Maratha leader, the general Santaji

Santaji Mahaloji Ghorpade,(1645–1696) popularly known as ‘Santajirao’ or ‘Santaji Ghorpade’, was the most celebrated Maratha warrior and the sixth Sarsenapati of the Maratha Empire during Rajaram's regime. His name became inseparable f ...

, inflicted the punishment for breaches in military discipline. The contemporary historian Khafi Khan

Muhammad Hashim (c. 1664–1732), better known by his title Khafi Khan, was an Indo-Persian historian of Mughal India. His career began about 1693–1694 as a clerk in Bombay. He served predominantly in Gujarat and the Deccan regions, including th ...

reported that "for a trifling offense he antajiwould cast a man under the feet of an elephant."

The early-19th-century writer Robert Kerr relates how the king of

The early-19th-century writer Robert Kerr relates how the king of Goa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

"keeps certain elephants for the execution of malefactors. When one of these is brought forth to dispatch a criminal, if his keeper desires that the offender be destroyed speedily, this vast creature will instantly crush him to atoms under his foot; but if desired to torture him, will break his limbs successively, as men are broken on the wheel

The breaking wheel or execution wheel, also known as the Wheel of Catherine or simply the Wheel, was a torture method used for public execution primarily in Europe from antiquity through the Middle Ages into the early modern period by breakin ...

." The naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste.

His works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including two prominent Fr ...

cited this flexibility of purpose as evidence that elephants were capable of "human reasoning, atherthan a simple, natural instinct".

Such executions were often held in public as a warning to any who may transgress. To that end, many of the elephants were especially large, often weighing in excess of nine tons. The executions were intended to be, and often were, gruesome. They were sometimes preceded by torture publicly inflicted by the same elephant used for the execution. An account of one such torture-and-execution at Baroda

Vadodara (), also known as Baroda, is the second largest city in the Indian state of Gujarat. It serves as the administrative headquarters of the Vadodara district and is situated on the banks of the Vishwamitri River, from the state capital ...

in 1814 has been preserved in ''The Percy Anecdotes'':

The use of elephants as executioners continued well into the latter half of the 19th century. During an expedition to central India in 1868, Louis Rousselet

Louis-Théophile Marie Rousselet (1845-1929) was a French traveller, writer, photographer and pioneer of the darkroom. His photographic work now commands high prices. Many of his drawings and photographs were made into engravings by others.

Li ...

described the execution of a criminal by an elephant. A sketch depicting the execution showed the condemned being forced to place his head upon a pedestal, and then being held there while an elephant crushed his head underfoot. The sketch was made into a woodcut

Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas that ...

and printed in "Le Tour du Monde

''Le Tour du monde, nouveau journal des voyages'' was a French weekly travel journal first published in January 1860.Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

''.

The growing power of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

led to the decline and eventual end of elephant executions in India. Writing in 1914, Eleanor Maddock noted that in Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

, since the arrival of Europeans, "many of the old customs are disappearing – and one of these is the dreadful custom of the execution of criminals by an elephant trained for the purpose and which was known by the hereditary name of 'Gunga Rao'."

= Sri Lanka

= Elephants were widely used across the

Elephants were widely used across the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

and South Asia as a method of execution. The English sailor Robert Knox

Robert Knox (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in the Burke and Hare murders. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox eventually partnered with anatomist and former teache ...

, writing in 1681, described a method of execution by elephant which he had witnessed while being held captive in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

. Knox says the elephants he witnessed had their tusk

Tusks are elongated, continuously growing front teeth that protrude well beyond the mouth of certain mammal species. They are most commonly canine teeth, as with pigs and walruses, or, in the case of elephants, elongated incisors. Tusks share c ...

s fitted with "sharp Iron with a socket with three edges". After impaling the victim's body with its tusks, the elephant would "then tear it in pieces, and throw it limb from limb".

The 19th-century traveler James Emerson Tennent

Sir James Emerson Tennent, 1st Baronet, FRS (born James Emerson; 7 April 1804 – 6 March 1869) was a British politician and traveller born in Ireland. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 5 June 1862.

Life

The third son of William ...

comments that "a Kandyan ri Lankanchief, who was witness to such scenes, has assured us that the elephant never once applied his tusks, but, placing his foot on the prostrate victim, plucked off his limbs in succession by a sudden movement of his trunk." Knox's book depicts exactly this method of execution in a famous drawing, ''An Execution by an Eliphant''.

Writing in 1850, the British diplomat Henry Charles Sirr described a visit to one of the elephants that had been used by Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, the last king of Kandy

Kandy ( si, මහනුවර ''Mahanuwara'', ; ta, கண்டி Kandy, ) is a major city in Sri Lanka located in the Central Province. It was the last capital of the ancient kings' era of Sri Lanka. The city lies in the midst of hills ...

, to execute criminals. Crushing by elephant had been abolished by the British after they annexed the Kingdom of Kandy in 1815 but the king's execution elephant was still alive and evidently remembered its former duties. Sirr comments:

West Asia

During themedieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

period, executions by elephants were used by several West Asian imperial powers, including the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

, Seljuq Seljuk or Saljuq (سلجوق) may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* Seljuk (warlord) (d ...

and Timurid Timurid refers to those descended from Timur (Tamerlane), a 14th-century conqueror:

* Timurid dynasty, a dynasty of Turco-Mongol lineage descended from Timur who established empires in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent

** Timurid Empire of C ...

empires. When the Sassanid king Khosrau II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king (shah) of Iran, ruling fr ...

, who had a harem of 3,000 wives and 12,000 female slaves, demanded as a wife Hadiqah, the daughter of the Christian Arab Na'aman, Na'aman refused to permit his Christian daughter to enter the harem of a Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic on ...

; for this refusal, he was trampled to death by an elephant.

The practice appears to have been adopted in parts of the Muslim Middle East. Rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

Petachiah of Ratisbon Petachiah of Regensburg, also known as Petachiah ben Yakov, Moses Petachiah, and Petachiah of Ratisbon, was a German rabbi of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries CE. At some point he left his place of birth, Regensburg in Bavaria, and settl ...

, a 12th-century Jewish traveler, reported an execution by this means during his stay in Seljuk Seljuk or Saljuq (سلجوق) may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* Seljuk (warlord) (di ...

-ruled northern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

(modern Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

):

Western empires

Perdiccas

Perdiccas ( el, Περδίκκας, ''Perdikkas''; 355 BC – 321/320 BC) was a general of Alexander the Great. He took part in the Macedonian campaign against the Achaemenid Empire, and, following Alexander's death in 323 BC, rose to becom ...

, who became regent of Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

on the death of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

in 323 BC, had mutineers from the faction of Meleager

In Greek mythology, Meleager (, grc-gre, Μελέαγρος, Meléagros) was a hero venerated in his ''temenos'' at Calydon in Aetolia. He was already famed as the host of the Calydonian boar hunt in the epic tradition that was reworked by Ho ...

thrown to the elephants to be crushed in the city of Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

. The Roman writer Quintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus () was a Roman historian, probably of the 1st century, author of his only known and only surviving work, ''Historiae Alexandri Magni'', "Histories of Alexander the Great", or more fully ''Historiarum Alexandri Magni Macedon ...

relates the story in his ''Historiae Alexandri Magni

The ''Histories of Alexander the Great'' ( la, Historiae Alexandri Magni) is the only surviving extant Latin biography of Alexander the Great. It was written by the Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus in the 1st-century AD, but the earliest sur ...

'':

Similarly, the Roman writer Valerius Maximus

Valerius Maximus () was a 1st-century Latin writer and author of a collection of historical anecdotes: ''Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IX'' ("Nine books of memorable deeds and sayings", also known as ''De factis dictisque memorabilibus'' ...

records how the general Lucius Aemilius Paulus Macedonicus

Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus (c. 229 – 160 BC) was a two-time consul of the Roman Republic and a general who conquered Macedon, putting an end to the Antigonid dynasty in the Third Macedonian War.

Family

Paullus' father was Luciu ...

"after King Perseus

In Greek mythology, Perseus (Help:IPA/English, /ˈpɜːrsiəs, -sjuːs/; Greek language, Greek: Περσεύς, Romanization of Greek, translit. Perseús) is the legendary founder of Mycenae and of the Perseid dynasty. He was, alongside Cadmus ...

was vanquished n 167 BC

N, or n, is the fourteenth Letter (alphabet), letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is English alphabet# ...

for the same fault (desertion) threw men under elephants to be trampled ... And indeed military discipline needs this kind of severe and abrupt punishment, because this is how strength of arms stands firm, which, when it falls away from the right course, will be subverted."

Africa

In 240 BC, aCarthaginian army The term Carthaginian ( la, Carthaginiensis ) usually refers to a citizen of Ancient Carthage.

It can also refer to:

* Carthaginian (ship), a three-masted schooner built in 1921

* Insurgent privateer

Insurgent privateers ( es, corsarios insurgen ...

led by Hamilcar Barca

Hamilcar Barca or Barcas ( xpu, 𐤇𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕𐤟𐤁𐤓𐤒, ''Ḥomilqart Baraq''; –228BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman, leader of the Barcid family, and father of Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago. He was also father- ...

was fighting a coalition of mutinous soldiers and rebellious African cities led by Spendius

Spendius (died late 238BC) was a former Roman slave who led a rebel army against Carthage, in what is known as the Mercenary War. He escaped or was rescued from slavery in Campania and was recruited into the Carthaginian Army during the Fir ...

. After losing a battle when a force of Numidian

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunis ...

cavalry deserted to the Carthaginians, Spendius had 700 Carthaginian prisoners tortured to death. From this point, prisoners taken by the Carthaginians were trampled to death by their war elephant

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elephant ...

s. This unusual ferocity caused the conflict to be termed the "Truceless War".

There are fewer records of elephants being used as straightforward executioners for the civil population. One such example is mentioned by Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

and the deuterocanonical book of 3 Maccabees

3 Maccabees, el, Μακκαβαίων Γ´, translit=Makkabaíōn 3 also called the Third Book of Maccabees, is a book written in Koine Greek, likely in the 1st century BC in Roman Egypt. Despite the title, the book has nothing to do with the Ma ...

in connection with the Egyptian Jews

Egyptian Jews constitute both one of the oldest and youngest Jewish communities in the world. The historic core of the Jewish community in Egypt consisted mainly of Egyptian Arabic speaking Rabbanites and Karaites. Though Egypt had its own com ...

, though the story is likely apocryphal. 3 Maccabees describes an attempt by Ptolemy IV Philopator

egy, Iwaennetjerwymenkhwy Setepptah Userkare Sekhemankhamun Clayton (2006) p. 208.

, predecessor = Ptolemy III

, successor = Ptolemy V

, horus = ''ḥnw-ḳni sḫꜤi.n-sw-it.f'Khunuqeni sekhaensuitef'' The strong youth whose f ...

(ruled 221–204 BC) to enslave and brand Egypt's Jews with the symbol of Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

. When the majority of the Jews resisted, the king is said to have rounded them up and ordered them to be trampled on by elephants. The mass execution was ultimately thwarted, supposedly by the intervention of angels, following which Ptolemy took an altogether more forgiving attitude towards his Jewish subjects.3 Maccabees 6Collins, p. 122.

References

Sources

* Allsen, Thomas T. "The Royal Hunt in Eurasian History". University of Pennsylvania Press, May 2006. * Chevers, Norman. "A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence for Bengal and the Northwestern Provinces". Carbery, 1856. * Collins, John Joseph. "Between Athens and Jerusalem: Jewish Identity in the Hellenistic Diaspora". Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, October 1999. * * Eraly, Abraham. "Mughal Throne: The Saga of India's Great Emperors", Phoenix House, 2005. * * Hamilton, Alexander. "A New Account of the East Indies: Being the Observations and Remarks of Capt. Alexander Hamilton, from the Year 1688 to 1723". C. Hitch and A. Millar, 1744. * Kerr, Robert. "A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels". W. Blackwood, 1811. * Lee, Samuel (trans). "The Travels of Ibn Batuta". Oriental Translation Committee, 1829. * * Olivelle, Patrick (trans). "The Law Code of Manu". Oxford University Press, 2004. * Schimmel, Annemarie. "The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture". Reaktion Books, February 2004. * Tennent, Emerson James. "Ceylon: An Account of the Island Physical, Historical and Topographical". Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1860. {{DEFAULTSORT:Execution By Elephant Elephants Elephants in Indian culture Execution methods Social history of India Social history of Africa History of South Asia History of Southeast Asia History of Africa Torture Deaths due to elephant attacks Animal trainingNaravas

Naravas ( Old Libyan: ''Nrbs(h)''; , ) was a Numidian chief in the Mercenary War of the Carthaginian state. Naravas is the Greek form of Narbal or Naarbaal.

Alliance with Hamilcar Barca

During the Punic Wars, Naravas had joined the army of Spe ...

Naravas

Naravas ( Old Libyan: ''Nrbs(h)''; , ) was a Numidian chief in the Mercenary War of the Carthaginian state. Naravas is the Greek form of Narbal or Naarbaal.

Alliance with Hamilcar Barca

During the Punic Wars, Naravas had joined the army of Spe ...

Naravas

Naravas ( Old Libyan: ''Nrbs(h)''; , ) was a Numidian chief in the Mercenary War of the Carthaginian state. Naravas is the Greek form of Narbal or Naarbaal.

Alliance with Hamilcar Barca

During the Punic Wars, Naravas had joined the army of Spe ...

Livestock