Evacuation Day (New York) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Evacuation Day on November 25 marks the day in 1783 when the

Following the significant losses at the

Following the significant losses at the

Entry to the city under General

Entry to the city under General

Clifton Hood

in his essay on New York's Evacuation Day makes the following citation for John Van Arsdale's role in removing the Union Flag and replacing it with the Stars and Stripes: ''Rivington’s New York Gazette'', November 26, 1783; ''The Independent New-York Gazette'', November 29, 1783; Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, ''Gotham: A History of New York to 1898'' (New York, 1999): 259–61; Douglas Southall Freeman, ''George Washington: A Biography, v. 5, Victory with the Help of France'' (New York, 1952): 461; James Thomas Flexner, ''George Washington, v. 3, In the American Revolution (1775–1783)'' (Boston, 1967): 522–8. Van Arsdale has sometimes been identified as an Army enlisted man or an Army officer. The flag later joined the historic collection at

File:Bennett Park New York Manhattan Fort Washington Memorial Mark.jpg, Monument in Bennett Park marking the November 16, 1776, evacuation and the November 25, 1783 triumphal entry of the American forces

File:Washington's entry into New York 1783, Currier and Ives 1857.jpg, ''Washington's Entry into New York'' by Currier & Ives

File:George Washington by John Trumbull 1790.jpg, alt= American General George Washington stands in front of a white horse, with Bowling Green and the Battery in the background, on Evacuation Day, November 25, 1783, '' George Washington, Evacuation of New York'', by John Trumbull, 1790, New York City Hall

File:Henry Kirke Brown George Washington statue by David Shankbone.jpg,

A week later, on December 3, the British detachment under Captain James Duncan, under orders of Rear Admiral Robert Digby, evacuated

A week later, on December 3, the British detachment under Captain James Duncan, under orders of Rear Admiral Robert Digby, evacuated

Public celebrations were first held on the fourth anniversary in 1787, with the city's garrison performing a dress review and ''

Public celebrations were first held on the fourth anniversary in 1787, with the city's garrison performing a dress review and ''

The importance of the commemoration was waning in 1844, with the approach of the

The importance of the commemoration was waning in 1844, with the approach of the

As part of Evacuation Day celebrations in 1883 (on November 26), the ''

As part of Evacuation Day celebrations in 1883 (on November 26), the ''

An Unusable Past

Urban Elites, New York City’s Evacuation Day, and the Transformations of Memory Culture'',

The Founding Fathers of American Intelligence

* Steenshorne, Jennifer E

Evacuation Day

Happy Evacuation Day

–

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

departed from New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

on Manhattan Island

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the List of co ...

, after the end of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. In their wake, General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

triumphantly led the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

from his headquarters north of the city across the Harlem River

The Harlem River is an tidal strait in New York, United States, flowing between the Hudson River and the East River and separating the island of Manhattan from the Bronx on the New York mainland.

The northern stretch, also called the Spuyt ...

, and south through Manhattan to the Battery at its southern tip.

History

Background

Following the significant losses at the

Following the significant losses at the Battle of Long Island

The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was an action of the American Revolutionary War fought on August 27, 1776, at the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn, New Yor ...

on August 27, 1776, General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

retreated across the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Quee ...

by benefit of both a retreat and holding action by well-trained Maryland Line

The "Maryland Line" was a formation within the Continental Army, formed and authorized by the Second Continental Congress, meeting in the "Old Pennsylvania State House" (later known as "Independence Hall") in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in June ...

troops at Gowanus Creek and Canal and a night fog which obscured the barges and boats evacuating troops to Manhattan Island. On September 15, 1776, the British flag replaced the American atop Fort George, where it was to remain until Evacuation Day.

Washington's Continentals subsequently withdrew north and west out of the town and following the Battle of Harlem Heights

The Battle of Harlem Heights was fought during the New York and New Jersey campaign of the American Revolutionary War. The action took place on September 16, 1776, in what is now the Morningside Heights area and east into the future Harlem neigh ...

and later action at the river forts of Fort Washington and Fort Lee on the northwest corner of the island along the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

on November 16, 1776, evacuated Manhattan Island

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the List of co ...

. They headed north for Westchester County

Westchester County is located in the U.S. state of New York. It is the seventh most populous county in the State of New York and the most populous north of New York City. According to the 2020 United States Census, the county had a population ...

, fought a delaying action at White Plains, and retreated across New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

in the New York and New Jersey campaign

The New York and New Jersey campaign in 1776 and the winter months of 1777 was a series of American Revolutionary War battles for control of the Port of New York and the state of New Jersey, fought between British forces under General Sir Willi ...

.

For the remainder of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, much of what is now Greater New York was under British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

control. New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

(occupying then only the southern tip of Manhattan, up to what is today Chambers Street), became, under Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, Lord Howe and his brother Sir William Howe, General of the British Army, the British political and military center of operations in British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

. David Mathews

David Mathews ( – July 28, 1800) was an American lawyer and politician from New York City. He was a Loyalist during the American Revolutionary War and was the 43rd and last Colonial Mayor of New York City from 1776 until 1783. As New York Ci ...

was Mayor of New York

The mayor of New York City, officially Mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property ...

during the occupation. Many of the civilians who continued to reside in town were Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

.

On September 21, 1776, the city suffered a devastating fire of an uncertain origin after the evacuation of Washington's Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

at the beginning of the occupation. With hundreds of houses destroyed, many residents had to live in makeshift housing built from old ships. In addition, over 10,000 Patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American Revolution

* Patriot m ...

soldiers and sailors died on prison ships

A prison ship, often more accurately described as a prison hulk, is a current or former seagoing vessel that has been modified to become a place of substantive detention for convicts, prisoners of war or civilian internees. While many nation ...

in New York waters ( Wallabout Bay) during the occupation—more Patriots died on these ships than died in every single battle of the war, combined. These men are memorialized, and many of their remains are interred, at the Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument

The Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument is a war memorial at Fort Greene Park, in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. It commemorates more than 11,500 American prisoners of war who died in captivity aboard sixteen British prison ships during th ...

in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

.

British evacuation

In mid-August 1783,Sir Guy Carleton

Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester (3 September 1724 – 10 November 1808), known between 1776 and 1786 as Sir Guy Carleton, was an Anglo-Irish soldier and administrator. He twice served as Governor of the Province of Quebec, from 1768 to 177 ...

, the last British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

and Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

commander in the former British America

British America comprised the colonial territories of the English Empire, which became the British Empire after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, in the Americas fro ...

, received orders from his superiors in London for the evacuation of New York. He informed the President of the Confederation Congress that he was proceeding with the subsequent withdrawal of refugees, liberated slaves, and military personnel as fast as possible, but that it was not possible to give an exact date because the number of refugees entering the city recently had increased dramatically (more than 29,000 Loyalist refugees were eventually evacuated from the city). The British also evacuated over 3,000 Black Loyalist

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the C ...

s, former slaves they had liberated from the Americans, to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, East Florida

East Florida ( es, Florida Oriental) was a colony of Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of Spanish Florida from 1783 to 1821. Great Britain gained control of the long-established Spanish colony of ''La Florida'' in 1763 as part of ...

, the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

, and London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, and refused to return them to their American slaveholders and overseers as the provisions of the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

had required them to do. The Black Brigade were among the last to depart.

Carleton gave a final evacuation date of 12:00 noon on November 25, 1783. An anecdote by New York physician Alexander Anderson Alexander Anderson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Alexander Anderson (illustrator) (1775–1870), American illustrator

* Alexander Anderson (poet) (1845–1909), Scottish poet

* Alexander Anderson (cartoonist) (1920–2010), American car ...

told of a scuffle between a British officer and the proprietress of a boarding house, as she defiantly raised her own American flag before noon. Following the departure of the British, the city was secured by American troops under the command of General Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following the ...

.

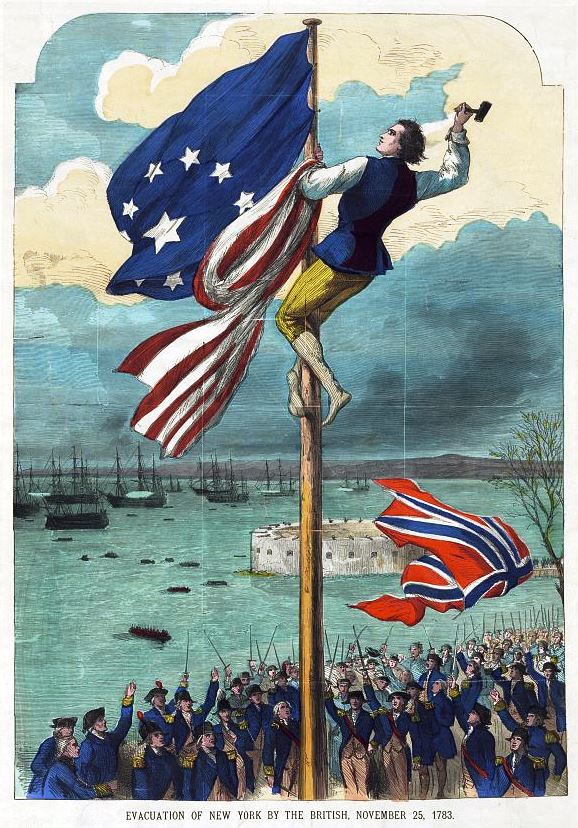

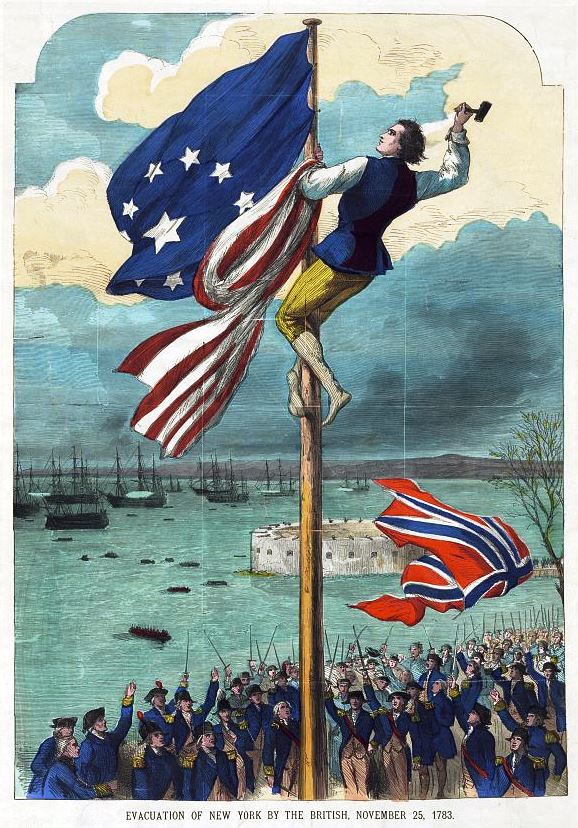

Legendary flag-raising

Entry to the city under General

Entry to the city under General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

was delayed until a still-flying British Union Flag

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

could be removed. The flag had been nailed to a flagpole at Fort George on the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan. The pole was greased as a final act of defiance. After a number of men attempted to tear down the British colors, wooden cleats were cut and nailed to the pole and, with the help of a ladder, an army veteran, John Van Arsdale

John Jacob Van Arsdale (1756-1836) was an American Revolutionary War soldier, noted for his legendary participation in the Evacuation Day flag-raising in 1783. From Cornwall, New York, he participated in the Benedict Arnold's expedition to Quebec ...

, was able to ascend the pole, remove the flag, and replace it with the Stars and Stripes before the British fleet had completely sailed out of sight.Hood, C. 2004, p. 6Clifton Hood

in his essay on New York's Evacuation Day makes the following citation for John Van Arsdale's role in removing the Union Flag and replacing it with the Stars and Stripes: ''Rivington’s New York Gazette'', November 26, 1783; ''The Independent New-York Gazette'', November 29, 1783; Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, ''Gotham: A History of New York to 1898'' (New York, 1999): 259–61; Douglas Southall Freeman, ''George Washington: A Biography, v. 5, Victory with the Help of France'' (New York, 1952): 461; James Thomas Flexner, ''George Washington, v. 3, In the American Revolution (1775–1783)'' (Boston, 1967): 522–8. Van Arsdale has sometimes been identified as an Army enlisted man or an Army officer. The flag later joined the historic collection at

Scudder's American Museum

Scudder's American Museum was a museum located in New York City from 1810 to 1841, when it was purchased by P.T. Barnum and transformed into the very successful Barnum's American Museum.

Before Scudder

The roots of the museum date back to 1791 ...

but was destroyed in a fire in 1865. The same day, a liberty pole

A liberty pole is a wooden pole, or sometimes spear or lance, surmounted by a "cap of liberty", mostly of the Phrygian cap. The symbol originated in the immediate aftermath of the assassination of the Roman dictator Julius Caesar by a group of R ...

with a flag was erected at New Utrecht Reformed Church

New Utrecht Reformed Church is the fourth oldest Reformed Church in America congregation and is located in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, New York. The church was established in 1677 by ethnic Dutch residents in the town of New Utrecht, Brooklyn, several ...

; its successor still stands there. Another liberty pole was raised in Jamaica, Queens, in a celebration that December.

Washington's entry

Finally, seven years after the retreat fromManhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

on November 16, 1776, General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and Governor of New York George Clinton reclaimed Fort Washington on the northwest corner of Manhattan Island

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the List of co ...

and then led the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

in a triumphal procession march down the road through the center of the island onto Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

in the Town to the Battery. The evening of Evacuation Day, Clinton hosted a public dinner at Fraunces Tavern, which Washington attended. It concluded with thirteen

Thirteen or 13 may refer to:

* 13 (number), the natural number following 12 and preceding 14

* One of the years 13 BC, AD 13, 1913, 2013

Music

* 13AD (band), an Indian classic and hard rock band

Albums

* ''13'' (Black Sabbath album), 2013

* ...

toasts, according to a contemporary account in '' Rivington's Gazette'', the company drinking to:

# The United States of America.

# His most Christian Majesty.

# The United Netherlands.

# The king of Sweden.

# The Continental Army.

# The Fleets and Armies of France, which have served in America.

# The Memory of those Heroes who have fallen for our Freedom.

# May our Country be grateful to her military children.

# May Justice support what Courage has gained.

# The Vindicators of the Rights of Mankind in every Quarter of the Globe.

# May America be an Asylum to the persecuted of the Earth.

# May a close Union of the States guard the Temple they have erected to Liberty.

# May the Remembrance of THIS DAY be a Lesson to Princes.

The morning after, Washington had a public breakfast meeting with Hercules Mulligan

Hercules Mulligan (September 25, 1740March 4, 1825) was an Irish-American tailor and spy during the American Revolutionary War. He was a member of the Sons of Liberty.

Early life

Born in Coleraine in the north of Ireland to Hugh and Sarah Mull ...

, which helped dispel suspicions about the tailor and spy.

Gallery

Henry Kirke Brown

Henry Kirke Brown (February 24, 1814 in Leyden, Massachusetts – July 10, 1886 in Newburgh, New York) was an American sculptor.

Life

He began to paint portraits while still a boy, studied painting in Boston under Chester Harding, learned a lit ...

's ''George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

'' in Union Square

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

commemorates Washington's entrance to the city on Evacuation Day

Aftermath

A week later, on December 3, the British detachment under Captain James Duncan, under orders of Rear Admiral Robert Digby, evacuated

A week later, on December 3, the British detachment under Captain James Duncan, under orders of Rear Admiral Robert Digby, evacuated Governors Island

Governors Island is a island in New York Harbor, within the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is located approximately south of Manhattan Island, and is separated from Brooklyn to the east by the Buttermilk Channel. The National Park ...

, the last of part of the-then City of New York to be occupied, and afterward Major-General Guy Carleton departed Staten Island on December 5.

It is claimed a British gunner fired the last shot of the Revolution either on Evacuation Day or when the last British ships left a week later, loosing a cannon at jeering crowds gathered on the shore of Staten Island as his ship passed through the Narrows

__NOTOC__

The Narrows is the tidal strait separating the boroughs of Staten Island and Brooklyn in New York City, United States. It connects the Upper New York Bay and Lower New York Bay and forms the principal channel by which the Hudson Riv ...

at the mouth of New York Harbor

New York Harbor is at the mouth of the Hudson River where it empties into New York Bay near the East River tidal estuary, and then into the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of the United States. It is one of the largest natural harbors in t ...

, though the shot fell well short of the shore. This has been described by historians as an urban legend.

On December 4, at Fraunces Tavern

Fraunces Tavern is a museum and restaurant in New York City, situated at 54 Pearl Street (Manhattan), Pearl Street at the corner of Broad Street (Manhattan), Broad Street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhatt ...

, at Pearl and Broad Streets, General Washington formally said farewell to his officers with a short statement, taking each one of his officers and official family by the hand. Later, Washington headed south, being cheered and fêted on his way at many stops in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

and Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. By December 23, he arrived in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, where the Confederation Congress was then meeting at the Maryland State House

The Maryland State House is located in Annapolis, Maryland. It is the oldest U.S. state capitol in continuous legislative use, dating to 1772 and houses the Maryland General Assembly, plus the offices of the Governor and Lieutenant Governor. In ...

to consider the terms of the Treaty of Paris. At their session in the Old Senate Chamber, he made a short statement and offered his sword and the papers of his commission to the President and the delegates, thereby resigning as commander-in-chief. He then retired to his plantation home, Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on ...

, in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

.

Commemoration

Early popularity

Public celebrations were first held on the fourth anniversary in 1787, with the city's garrison performing a dress review and ''

Public celebrations were first held on the fourth anniversary in 1787, with the city's garrison performing a dress review and ''feu de joie

A feu de joie (French: "fire of joy") is a form of formal celebratory gunfire consisting of a celebratory rifle salute, described as a "running fire of guns." As soldiers fire into the air sequentially in rapid succession, the cascade of blank r ...

'', and in the context of a Federalist push for constitutional ratification following the Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

. On Evacuation Day 1790, the Veteran Corps of Artillery of the State of New York

The Veteran Corps of Artillery of the State of New York (VCASNY) is an American historic militia organization founded at the end of the American Revolutionary War for the purpose of preventing another British invasion of New York City.

At the ti ...

was founded, and it played a significant role in later commemorations.

The British Fort George at Bowling Green was also demolished in 1790, and in that year the "Battery Flagstaff" was built adjacent on newly reclaimed land at the Battery. It was privately managed by William and then Lois Keefe. Referred to colloquially as "the churn", as it resembled to some a gigantic butter churn, Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

described a September 1804 visit to the commemorative flagpole in his ''A History of New York __NOTOC__

''A History of New York'', subtitled ''From the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty'', is an 1809 literary parody on the history of New York City by Washington Irving. Originally published under the pseudonym Diedrich ...

'' as "The standard of our city, reserved, like a choice handkerchief, for days of gala, hung motionless on the flag-staff, which forms the handle to a gigantic churn

Churn may refer to:

* Churn drill, large-diameter drilling machine large holes appropriate for holes in the ground

Dairy-product terms

* Butter churn, device for churning butter

* Churning (butter), the process of creating butter out of mil ...

". In 1809, a new flagstaff further east on the Battery was erected with a decorative gazebo

A gazebo is a pavilion structure, sometimes octagonal or turret-shaped, often built in a park, garden or spacious public area. Some are used on occasions as bandstands.

Etymology

The etymology given by Oxford Dictionaries (website), Oxford D ...

, and was operated as a concession until it was demolished about 1825. The military band led by Patrick Moffat of George Izard

George Izard (October 21, 1776 – November 22, 1828) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served as the second governor of Arkansas Territory from 1825 to 1828. He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 18 ...

's Second Regiment of Artillery sometimes held evening concerts. The Battery Flagstaff commemorated Evacuation Day, and was the site of the city's annual flag-raising celebration for over a century. A flag-raising was held twice a year, on Evacuation Day and on the Fourth of July

Independence Day (colloquially the Fourth of July) is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the Declaration of Independence, which was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing the United States ...

, and after 1853 flag-raisings on these days were also held at The Blockhouse

''The Blockhouse'' is a 1973 drama film directed by Clive Rees and starring Peter Sellers and Charles Aznavour. It is based on a 1955 novel by Jean-Paul Clébert. It was filmed entirely in Guernsey in the Channel Islands and was entered into t ...

further north. John Van Arsdale is said to have been a regular flag-raiser at the early commemorations.

The Scudder's American Museum

Scudder's American Museum was a museum located in New York City from 1810 to 1841, when it was purchased by P.T. Barnum and transformed into the very successful Barnum's American Museum.

Before Scudder

The roots of the museum date back to 1791 ...

/ Barnum's American Museum

Barnum's American Museum was located at the corner of Broadway, Park Row, and Ann Street in what is now the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City, from 1841 to 1865. The museum was owned by famous showman P. T. Barnum, who purchas ...

held what it claimed was the original 1783 Evacuation Day flag until the museum's burning in 1865, and flew it on Evacuation Day and the Fourth of July.

On Evacuation Day 1811, the newly completed Castle Clinton

Castle Clinton (also known as Fort Clinton and Castle Garden) is a circular sandstone fort within Battery Park at the southern end of Manhattan in New York City. Built from 1808 to 1811, it was the first American immigration station, predating ...

was dedicated with the firing of its first gun salute

A gun salute or cannon salute is the use of a piece of artillery to fire shots, often 21 in number (''21-gun salute''), with the aim of marking an honor or celebrating a joyful event. It is a tradition in many countries around the world.

Histo ...

.

On Evacuation Day 1830 (or rather, on November 26 due to inclement weather), thirty thousand New Yorkers gathered on a march to Washington Square Park

Washington Square Park is a public park in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan, New York City. One of the best known of New York City's public parks, it is an icon as well as a meeting place and center for cultural activity. ...

in celebration of that year's July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

in France.

For over a century the event was commemorated annually with patriotic and political connotations, as well as embracing a general holiday atmosphere. Sometimes featured were greasy pole

Greasy pole, grease pole, or greased pole refers to a tall pole that has been made slippery with grease or other lubricants and thus difficult to grip. More specifically, it is the name of several events that involve staying on, climbing up, w ...

climbing contests for boys to recreate taking down the Union Jack

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

. Evacuation Day also became a time for theatrical spectacle, with for example an 1832 Bowery Theatre

The Bowery Theatre was a playhouse on the Bowery in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York City. Although it was founded by rich families to compete with the upscale Park Theatre, the Bowery saw its most successful period under the populi ...

double bill of Junius Brutus Booth

Junius Brutus Booth (1 May 1796 – 30 November 1852) was an English stage actor. He was the father of actor John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. His other children included Edwin Booth, the foremost tragedian of ...

and Thomas D. Rice

Thomas Dartmouth Rice (May 20, 1808 – September 19, 1860) was an American performer and playwright who performed in blackface and used African American vernacular speech, song and dance to become one of the most popular minstrel show ente ...

. David Van Arsdale is said to have raised the flag after his father's death in 1836. There was also a traditional parade from near the current Cooper Union

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (Cooper Union) is a private college at Cooper Square in New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-supported École Polytechnique in ...

down the Bowery

The Bowery () is a street and neighborhood in Lower Manhattan in New York City. The street runs from Chatham Square at Park Row, Worth Street, and Mott Street in the south to Cooper Square at 4th Street in the north.Jackson, Kenneth L. "Bow ...

to the Battery.

Mid-19th century and decline

The importance of the commemoration was waning in 1844, with the approach of the

The importance of the commemoration was waning in 1844, with the approach of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

of 1846–1848.

However, the dedication of the monument to William J. Worth, the Mexican–American War general, at Madison Square

Madison Square is a town square, public square formed by the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway at 23rd Street (Manhattan), 23rd Street in the New York City borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan. The square ...

was purposely held on Evacuation Day 1857.

In August 1863, the Battery Flagstaff was destroyed by a lightning strike; it was subsequently replaced.

Before it was a national holiday, Thanksgiving was proclaimed at various dates by state governors – as early as 1847, New York held Thanksgiving on the same date as Evacuation Day, a convergence happily noted by Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among t ...

, writing in the ''Brooklyn Eagle

:''This article covers both the historical newspaper (1841–1955, 1960–1963), as well as an unrelated new Brooklyn Daily Eagle starting 1996 published currently''

The ''Brooklyn Eagle'' (originally joint name ''The Brooklyn Eagle'' and ''King ...

''. The observance of the date was also diminished by the Thanksgiving Day Proclamation by 16th President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

on October 3, 1863, that called on Americans "in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of thanksgiving." That year, Thursday fell on November 26. In later years, Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in the United States, Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Philippines. It is also observed in the Netherlander town of Leiden and ...

was celebrated on or near the 25th, making Evacuation Day redundant.

On Evacuation Day 1864, the Booth brothers held a performance of ''Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

'' at the Winter Garden Theatre

The Winter Garden Theatre is a Broadway theatre at 1634 Broadway in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It opened in 1911 under designs by architect William Albert Swasey. The Winter Garden's current design dates to 1922, when ...

to raise funds for the Shakespeare statue later placed in Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West Side, Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the List of New York City parks, fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban par ...

. That same day, Confederate saboteurs attempted to burn down the city, lighting an adjoining building on fire and for a time disturbing the performance.

On Evacuation Day 1876, the statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park was dedicated.

A traditional children's rhyme of the era was:''It's Evacuation Day, when the British ran away,Over time, the celebration and its anti-British sentiments became associated with the local Irish American community. This community's embrace also may have inspired Evacuation Day in Boston, which began to be celebrated there in 1901, and taking advantage of the anniversary of the lifting of the

Please, dear Master, give us holiday!

Siege of Boston

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War. New England militiamen prevented the movement by land of the British Army, which was garrisoned in what was then the peninsular town ...

in 1776, which was by coincidence on Saint Patrick's Day

Saint Patrick's Day, or the Feast of Saint Patrick ( ga, Lá Fhéile Pádraig, lit=the Day of the Festival of Patrick), is a cultural and religious celebration held on 17 March, the traditional death date of Saint Patrick (), the foremost patr ...

.

Centennial and 20th century fading

As part of Evacuation Day celebrations in 1883 (on November 26), the ''

As part of Evacuation Day celebrations in 1883 (on November 26), the ''George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

'' statue was unveiled in front of what is now Federal Hall National Memorial

Federal Hall is a historic building at 26 Wall Street in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City. The current Greek Revival–style building, completed in 1842 as the Custom House, is operated by the National Park Service as a na ...

.

In the 1890s, the anniversary was celebrated in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

at Battery Park

The Battery, formerly known as Battery Park, is a public park located at the southern tip of Manhattan Island in New York City facing New York Harbor. It is bounded by Battery Place on the north, State Street on the east, New York Harbor to ...

with the raising of the Stars and Stripes by Christopher R. Forbes, the great grandson of John Van Arsdale, with the assistance of a Civil War veterans' association from Manhattan—the Anderson Zouaves

The 62nd New York Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It is also known as the Anderson Zouaves.

Organization

It was raised under special authority of the War Department in New ...

. John Lafayette Riker

John Lafayette Riker (August 15, 1824 – May 31, 1862) was an American attorney and an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was killed in action at the Battle of Fair Oaks during the Peninsula Campaign.

Early life

Joh ...

, the original commander of the Anderson Zouaves, was also a grandson of John Van Arsdale. Riker's older brother was the New York genealogist James Riker

James Riker (New York City, May 11, 1822 – 1889) was a New York historian and genealogist. His father, James Riker (Snr) was a merchant and landowner descended from early Dutch settlers. Riker left school at the age of sixteen to work in his f ...

, who authored ''Evacuation Day, 1783'' for the spectacular 100th anniversary celebrations of 1883, which were ranked as “one of the great civic events of the nineteenth century in New York City.” David Van Arsdale had died in November 1883 just before the centennial, having helped revive the event the year previous, and he was succeeded by his grandson.

On Evacuation Day 1893, the ''Nathan Hale

Nathan Hale (June 6, 1755 – September 22, 1776) was an American Patriot, soldier and spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission in New York City but was captured b ...

'' statue in City Hall Park was unveiled.

In 1895, Asa Bird Gardiner

Asa Bird Gardiner (September 30, 1839 – May 24, 1919) was a controversial American soldier, attorney, and district attorney for New York County (a.k.a. the Borough of Manhattan) from 1898 to 1900.

He received the Medal of Honor for his service ...

disputed the rights to organize the flag-raising, claiming that his organization, the General Society of the War of 1812

The General Society of the War of 1812 is an American non-profit corporation and charitable organization of male descendants of American veterans of the War of 1812. The General Society was founded on January 9, 1854, at the Congress Hall ...

, were the true heirs of the Veteran Corps of Artillery.

In 1900, Christopher R. Forbes was denied the honor of raising the flag at the Battery on Independence Day

An independence day is an annual event commemorating the anniversary of a nation's independence or statehood, usually after ceasing to be a group or part of another nation or state, or more rarely after the end of a military occupation. Man ...

and on Evacuation Day and it appears that neither he nor any Veterans' organization associated with the Van Arsdale-Riker family or the Anderson Zouaves took part in the ceremony after this time. In 1901, Forbes raised the flag at the dedication of Bennett Park.

In the early 20th century, the 161-foot flagpole used was the mast of the 1901 America's Cup

The America's Cup, informally known as the Auld Mug, is a trophy awarded in the sport of sailing. It is the oldest international competition still operating in any sport. America's Cup match races are held between two sailing yachts: one f ...

defender ''Constitution'' designed by Herreshoff, replacing a wooden pole struck by lightning in 1909. The event was officially celebrated for the last time on November 25, 1916 with a march down Broadway for a flag raising ceremony by sixty members of the Old Guard. Future commemorations were forestalled by the American entry into World War I

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry

...

and the alliance with Britain. The position of the flagstaff at this time was described as near Battery Park's sculptures of John Ericsson

John Ericsson (born Johan Ericsson; July 31, 1803 – March 8, 1889) was a Swedish-American inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Ericsson collaborated on the design of the railroad steam locomotive ''Novelty'', which com ...

and Giovanni da Verrazzano

Giovanni da Verrazzano ( , , often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1485–1528) was an Italian ( Florentine) explorer of North America, in the service of King Francis I of France.

He is renowned as the first European to explore the Atlantic ...

. The commemorative flagpole was still listed as an attraction on a map of Battery Park in the WPA ''New York City Guide'' of 1939.

On Evacuation Day 1922, the main monument at Battle Pass

In the video game industry, a battle pass is a type of monetization approach that provides additional content for a game usually through a tiered system, rewarding the player with in-game items for playing the game and completing specific chal ...

in Brooklyn's Prospect Park was dedicated.

The flagpole was removed during the 1940-1952 construction of Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel

The Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel, officially the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel and commonly referred to as the Battery Tunnel or Battery Park Tunnel, is a tolled tunnel in New York City that connects Red Hook in Brooklyn with the Battery in Manhatta ...

and the relandscaping of the park. In 1955, the 102-foot Marine Flagstaff was erected in the approximate area of the one formerly commemorating Evacuation Day. Later, City Council President Paul O'Dwyer expressed interest in a restored flagpole for the 1976 United States Bicentennial

The United States Bicentennial was a series of celebrations and observances during the mid-1970s that paid tribute to historical events leading up to the creation of the United States of America as an independent republic. It was a central event ...

. A bicentennial of Evacuation Day in 1983 featured the labor leader Harry Van Arsdale Jr. A commemorative plaque marking Evacuation Day was put on a flagpole at Bowling Green

A bowling green is a finely laid, close-mown and rolled stretch of turf for playing the game of bowls.

Before 1830, when Edwin Beard Budding of Thrupp, near Stroud, UK, invented the lawnmower, lawns were often kept cropped by grazing sheep ...

in 1996.

The Sons of the Revolution

Sons of the Revolution is a hereditary society which was founded in 1876 and educates the public about the American Revolution. The General Society Sons of the Revolution headquarters is a Pennsylvania non-profit corporation

located at Willia ...

fraternal organization continues to hold an annual 'Evacuation Day Dinner' at Fraunces Tavern

Fraunces Tavern is a museum and restaurant in New York City, situated at 54 Pearl Street (Manhattan), Pearl Street at the corner of Broad Street (Manhattan), Broad Street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhatt ...

, and giving the thirteen toasts from 1783.

21st century and renewed efforts

Though little celebrated in the previous century, the 225th anniversary of Evacuation Day was commemorated on November 25, 2008, with searchlight displays in New Jersey and New York at key high points. The searchlights are modern commemorations of the bonfires that served as a beacon signal system at many of these same locations during the revolution. The seven New Jersey Revolutionary War sites are Beacon Hill inSummit

A summit is a point on a surface that is higher in elevation than all points immediately adjacent to it. The topography, topographic terms acme, apex, peak (mountain peak), and zenith are synonymous.

The term (mountain top) is generally used ...

, South Mountain Reservation

South Mountain Reservation, covering 2,110, 2,112, 2,000, 2,100, or 2,047 acres (8.539, 8.546, 8.094, 8.498, or 8.284 km2) depending on who you ask, is a nature reserve on the Rahway River that is part of the Essex County Park System, New Jersey, ...

in South Orange, Fort Nonsense in Morristown, Washington Rock in Green Brook, the Navesink Twin Lights

The Navesink Twin Lights is a non-operational lighthouse and museum located in Highlands, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States, overlooking Sandy Hook Bay, the entrance to the New York Harbor and the Atlantic Ocean. The Twin Lights, as the ...

, Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

, and Ramapo Mountain State Forest

Ramapo Mountain State Forest is a state forest in Bergen and Passaic Counties in New Jersey. The park is operated and maintained by the New Jersey Division of Parks and Forestry.

The park offers hiking, hunting, canoeing, fishing (including i ...

near Oakland. The five New York locations which contributed to the celebration are; Bear Mountain State Park

Bear Mountain State Park is a state park located on the west bank of the Hudson River in Rockland and Orange counties, New York. The park offers biking, hiking, boating, picnicking, swimming, cross-country skiing, cross-country running, sledd ...

, Storm King State Park, Scenic Hudson's Spy Rock (Snake Hill) in New Windsor, Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site

Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site, also called Hasbrouck House, is located in Newburgh, New York overlooking the Hudson River. George Washington lived there while he was in command of the Continental Army during the final year of the A ...

in Newburgh, Scenic Hudson's Mount Beacon

Beacon Mountain, locally Mount Beacon, is the highest peak of Hudson Highlands, located south of City of Beacon, New York, in the Town of Fishkill. Its two summits rise above the Hudson River behind the city and can easily be seen from Newbu ...

.

The renaming of a portion of Bowling Green

A bowling green is a finely laid, close-mown and rolled stretch of turf for playing the game of bowls.

Before 1830, when Edwin Beard Budding of Thrupp, near Stroud, UK, invented the lawnmower, lawns were often kept cropped by grazing sheep ...

, a street in Lower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan (also known as Downtown Manhattan or Downtown New York) is the southernmost part of Manhattan, the central borough for business, culture, and government in New York City, which is the most populated city in the United States with ...

to Evacuation Day Plaza was proposed by Arthur R. Piccolo, the chairman of the Bowling Green Association, and James S. Kaplan of the Lower Manhattan Historical Society. The proposal was initially turned down by the New York City Council

The New York City Council is the lawmaking body of New York City. It has 51 members from 51 council districts throughout the five Borough (New York City), boroughs.

The council serves as a check against the Mayor of New York City, mayor in a may ...

in 2016 because the council's rules for street renaming specify that a renamed street must commemorate a person, an organization, or a cultural work. However, with the support of Councilwoman Margaret Chin

Margaret S. Chin (born May 26, 1953) is a Hong Kong American politician who served as a council member for the 1st district of the New York City Council. A Democrat, she and Queens Council member Peter Koo comprised the Asian American deleg ...

, and after supporters of the renaming pointed to streets and plazas named after "Do the Right Thing Way", "Diversity Plaza", "Hip Hop Boulevard", and " Ragamuffin Way", the council reversed its decision and approved the renaming of the street on February 5, 2016.

References

Notes

Bibliography

*Hood, Clifton.An Unusable Past

Urban Elites, New York City’s Evacuation Day, and the Transformations of Memory Culture'',

Journal of Social History

''The Journal of Social History'' was founded in 1967 and has been edited since then by Peter Stearns. The journal covers social history in all regions and time periods.

Articles in the journal frequently combine sociohistorical analysis between ...

, Summer 2004.

*

*

External links

*The Founding Fathers of American Intelligence

* Steenshorne, Jennifer E

Evacuation Day

New York State Archives

The New York State Archives is a unit of the Office of Cultural Education within the New York State Education Department, with its main facility located in the Cultural Education Center on Madison Avenue in Albany, New York, United States. The Ne ...

, Fall 2010, volume 10

*

*Happy Evacuation Day

–

Sarah Vowell

Sarah Jane Vowell (born December 27, 1969) is an American author, journalist, essayist, social commentator and voice actress. She has written seven nonfiction books on American history and culture. She was a contributing editor for the radio pro ...

on The Daily Show

''The Daily Show'' is an American late-night talk and satirical news television program. It airs each Monday through Thursday on Comedy Central with release shortly after on Paramount+. ''The Daily Show'' draws its comedy and satire form from ...

, November 17, 2011

{{Authority control

1783 in New York (state)

American Revolution anniversaries

Bowling Green (New York City)

Holidays related to the American Revolution

New York (state) culture

New York (state) historical anniversaries

New York (state) in the American Revolution

November observances

Observances in New York City

The Battery (Manhattan)