Europeans in Medieval China on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Given textual and archaeological evidence, it is thought that thousands of Europeans lived in

Given textual and archaeological evidence, it is thought that thousands of Europeans lived in

Given textual and archaeological evidence, it is thought that thousands of Europeans lived in

Given textual and archaeological evidence, it is thought that thousands of Europeans lived in Imperial China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

during the Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fifth ...

.Roux (1993), p. 465 These were people from countries traditionally belonging to the lands of Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

during the High

High may refer to:

Science and technology

* Height

* High (atmospheric), a high-pressure area

* High (computability), a quality of a Turing degree, in computability theory

* High (tectonics), in geology an area where relative tectonic uplift ...

to Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the Periodization, period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Eur ...

who visited, traded, performed Christian missionary

A Christian mission is an organized effort for the propagation of the Christian faith. Missions involve sending individuals and groups across boundaries, most commonly geographical boundaries, to carry on evangelism or other activities, such as ...

work, or lived in China. This occurred primarily during the second half of the 13th century and the first half of the 14th century, coinciding with the rule of the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

, which ruled over a large part of Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

and connected Europe with their Chinese dominion of the Yuan dynasty. Whereas the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

centered in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

maintained rare incidences of correspondence with the Tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

, Song

A song is a musical composition intended to be performed by the human voice. This is often done at distinct and fixed pitches (melodies) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs contain various forms, such as those including the repetitio ...

and Ming

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peop ...

dynasties of China, the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

sent several missionaries and embassies to the early Mongol Empire as well as to Khanbaliq

Khanbaliq or Dadu of Yuan () was the winter capital of the Yuan dynasty of China in what is now Beijing, also the capital of the People's Republic of China today. It was located at the center of modern Beijing. The Secretariat directly administ ...

(modern Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

), the capital of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. These contacts with the West were preceded by rare interactions between the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

and Hellenistic Greeks

Hellenistic Greece is the historical period of the country following Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the annexation of the classical Greek Achaean League heartlands by the Roman Republic. This culminated ...

and Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

.

Mainly located in places such as the Yuan capital of Karakorum

Karakorum (Khalkha Mongolian: Хархорум, ''Kharkhorum''; Mongolian Script:, ''Qaraqorum''; ) was the capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan dynasty in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in the ...

, European missionaries and merchants traveled around various parts of the Yuan dynasty and other Mongol-ruled khanates during a period of time referred to by historians as the "Pax Mongolica

The ''Pax Mongolica'' (Latin for "Mongol Peace"), less often known as ''Pax Tatarica'' ("Tatar Peace"), is a historiographical term modelled after the original phrase ''Pax Romana'' which describes the stabilizing effects of the conquests of the ...

". Perhaps the most important political consequence of this movement of peoples and intensified trade was the Franco-Mongol alliance

Several attempts at a Franco-Mongol alliance against the Islamic caliphates, their common enemy, were made by various leaders among the Frankish Crusaders and the Mongol Empire in the 13th century. Such an alliance might have seemed an obvious c ...

, although the latter never fully materialized, at least not in a consistent manner. The establishment of the Ming dynasty in 1368 and reestablishment of ethnic Han rule led to the cessation of European merchants and Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

missionaries living in China. Direct contact with Europeans was not renewed until Portuguese explorers

Portuguese maritime exploration resulted in the numerous territories and maritime routes recorded by the Portuguese as a result of their intensive maritime journeys during the 15th and 16th centuries. Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of Eu ...

and Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

arrived on Ming China's southern shores in the 1510s, during the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafarin ...

.

The Italian merchant Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

, preceded by his father and uncle Niccolò and Maffeo Polo, traveled to China during the Yuan dynasty. Marco Polo wrote a famous account of his travels there, as did the Franciscan friar Odoric of Pordenone

Odoric of Pordenone, OFM (1286–1331), also known as Odorico Mattiussi/Mattiuzzi, Odoricus of Friuli or Orderic of Pordenone, was an Italian late-medieval Franciscan friar and missionary explorer. He traveled through India, the Greater Sunda Is ...

and the merchant Francesco Balducci Pegolotti Pegolotti Pratica Ricc.2441 specimen half page.

Francesco Balducci Pegolotti (fl. 1290 – 1347), also Francesco di Balduccio, was a Florentine merchant and politician.

Life

His father, Balduccio Pegolotti, represented Florence in commercial neg ...

. The author John Mandeville

Sir John Mandeville is the supposed author of ''The Travels of Sir John Mandeville'', a travel memoir which first circulated between 1357 and 1371. The earliest-surviving text is in French.

By aid of translations into many other languages, the ...

also wrote about his travels to China, but he may have based these on preexisting accounts. In Khanbaliq, the Roman archdiocese was established by John of Montecorvino

John of Montecorvino or Giovanni da Montecorvino in Italian (1247 – 1328) was an Italian Franciscan missionary, traveller and statesman, founder of the earliest Latin Catholic missions in India and China, and archbishop of Peking. He convert ...

, who was later succeeded by Giovanni de Marignolli

Giovanni de' Marignolli ( la, Johannes Marignola;. ), variously anglicized as John of Marignolli or John of Florence, was a notable 14th-century Catholic European traveller to medieval China and India.

Life

Early life

Giovanni was born, probab ...

. Other Europeans such as André de Longjumeau

André de Longjumeau (also known as Andrew of Longjumeau in English) was a 13th-century Dominican missionary and diplomat and one of the most active Occidental diplomats in the East in the 13th century. He led two embassies to the Mongols: the fi ...

managed to reach the eastern borderlands of China in their diplomatic travels to the Yuan imperial court, while others such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, variously rendered in English as ''John of Pian de Carpine'', ''John of Plano Carpini'' or ''Joannes de Plano'' (c. 11851 August 1252), was a medieval Italian diplomat, archbishop and explorer and one of the firs ...

, Benedykt Polak

Benedict of Poland (Latin: ''Benedictus Polonus'', Polish ''Benedykt Polak'') (c. 1200 – c. 1280) was a Polish Franciscan friar, traveler, explorer, and interpreter.

He accompanied Giovanni da Pian del Carpine in his journey as delegate of ...

, and William of Rubruck

William of Rubruck ( nl, Willem van Rubroeck, la, Gulielmus de Rubruquis; ) was a Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer.

He is best known for his travels to various parts of the Middle East and Central Asia in the 13th century, including the ...

traveled instead to Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia was the name of a territory in the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China from 1691 to 1911. It corresponds to the modern-day independent state of Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. The historical region gained ''de facto' ...

. The Turkic Chinese Nestorian Christian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian N ...

Rabban Bar Sauma

Rabban Bar Ṣawma (Syriac language: , ; 1220January 1294), also known as Rabban Ṣawma or Rabban ÇaumaMantran, p. 298 (), was a Turkic Chinese ( Uyghur or possibly Ongud) monk turned diplomat of the "Nestorian" Church of the East in China. ...

was the first diplomat from China to reach the royal courts of the Christendom in the West.

Background

Hellenistic Greeks

Before the 13th century AD, instances of Europeans going to China or of Chinese going to Europe were very rare.Euthydemus I

Euthydemus I (Greek: , ''Euthydemos'') c. 260 BC – 200/195 BC) was a Greco-Bactrian king and founder of the Euthydemid dynasty. He is thought to have originally been a governor (Satrap) of Sogdia, who seized the throne by force from Diodotus I ...

, Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

ruler of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic-era Hellenistic Greece, Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Helleni ...

in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

during the 3rd century BC, led an expedition into the Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hydr ...

(modern Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

, China) in search of precious metals.W.W. Tarn (1966), ''The Greeks in Bactria and India'', reprint edition, London & New York: Cambridge University Press, pp 109–111. Greek influence as far east as the Tarim Basin at this time also seems to be confirmed by the discovery of the Sampul tapestry, a woolen wall hanging with the painting of a blue-eyed soldier, possibly a Greek, and a prancing centaur

A centaur ( ; grc, κένταυρος, kéntauros; ), or occasionally hippocentaur, is a creature from Greek mythology with the upper body of a human and the lower body and legs of a horse.

Centaurs are thought of in many Greek myths as being ...

, a common Hellenistic motif from Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the Cosmogony, origin and Cosmology#Metaphysical co ...

.Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), ''Sino-Platonic Papers'', No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp 15–16, ISSN 2157-9687. However, it is known that other Indo-European peoples

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

such as the Yuezhi

The Yuezhi (;) were an ancient people first described in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat ...

, Saka

The Saka ( Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who hist ...

, and Tocharians

The Tocharians, or Tokharians ( US: or ; UK: ), were speakers of Tocharian languages, Indo-European languages known from around 7600 documents from around 400 to 1200 AD, found on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang, China). ...

Xavier Tremblay (2007), "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th Century," in Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacker (eds), ''The Spread of Buddhism'', Leiden & Boston: Koninklijke Brill, p. 77, . inhabited the Tarim Basin before and after it was brought under Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive va ...

influence during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han

Emperor Wu of Han (156 – 29 March 87BC), formally enshrined as Emperor Wu the Filial (), born Liu Che (劉徹) and courtesy name Tong (通), was the seventh emperor of the Han dynasty of ancient China, ruling from 141 to 87 BC. His reign la ...

(r. 141–87 BC). Emperor Wu's diplomat Zhang Qian

Zhang Qian (; died c. 114) was a Chinese official and diplomat who served as an imperial envoy to the world outside of China in the late 2nd century BC during the Han dynasty. He was one of the first official diplomats to bring back valuable inf ...

(d. 113 BC) was sent to forge an alliance with the Yuezhi, a mission that was unsuccessful, but he brought back eyewitness reports of legacies of Hellenistic Greek civilization with his travels to "Dayuan

Dayuan (or Tayuan; ; Middle Chinese ''dâiC-jwɐn'' < LHC: ''dɑh-ʔyɑn'') is the Chinese " in the

Mitochondrial DNA analysis of ancient Sampula population in Xinjiang

" in ''Progress in Natural Science'', vol. 17, (August 2007), pp 927–33.Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), ''Sino-Platonic Papers'', No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 27 & footnote #46, ISSN 2157-9687. Seeming to confirm this link, from historical accounts it is known that

Roxane

" ''Articles on Ancient History''. Page last modified 17 August 2015. Retrieved on 8 September 2016.Strachan, Edward and Roy Bolton (2008), ''Russia and Europe in the Nineteenth Century'', London: Sphinx Fine Art, p. 87, . encouraged his soldiers and generals to marry local women; consequentially the later kings of the

, LIVIUS Articles of Ancient History. 28 October 2010. Retrieved on 14 November 2010. and giving the Byzantine Empire a monopoly on silk production in medieval Europe until the loss of its territories in Southern Italy. The Byzantine historian

According to the 9th-century '' Book of Roads and Kingdoms'' by

According to the 9th-century '' Book of Roads and Kingdoms'' by

In Zaytun, the first harbour of China, there was a small Genoese colony, mentioned in 1326 by André de Pérouse. The most famous Italian resident of the city was Andolo de Savignone, who was sent to the West by the Khan in 1336 to obtain "100 horses and other treasures." Following Savignone's visit, an ambassador was dispatched to China with one superb horse, which was later the object of

In Zaytun, the first harbour of China, there was a small Genoese colony, mentioned in 1326 by André de Pérouse. The most famous Italian resident of the city was Andolo de Savignone, who was sent to the West by the Khan in 1336 to obtain "100 horses and other treasures." Following Savignone's visit, an ambassador was dispatched to China with one superb horse, which was later the object of

Rabban bar Sauma: Mongol Envoy

" ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (online source). Accessed 6 September 2016. Bar Sauma, who spoke

Giovanni dei Marignolli: Italian Clergyman.

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Accessed 6 September 2016. * Emmerick, R. E. (2003) "Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed.), ''The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Fisher, William Bayne; John Andrew Boyle (1968). ''The Cambridge history of Iran''. London & New York: Cambridge University Press. . * Foltz, Richard (2010). ''Religions of the Silk Road''. Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition. . * Fontana, Michela (2011). ''Matteo Ricci: a Jesuit in the Ming Court''. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. . * * Gernet, Jacques (1962). H.M. Wright (trans), ''Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276''. Stanford: Stanford University Press. . * Glick, Thomas F; Steven John Livesey; Faith Wallis (2005). ''Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia''. London & New York: Routledge. . * Goody, Jack (2012). ''Metals, Culture, and Capitalism: an Essay on the Origins of the Modern World''. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press. . * * Hansen, Valerie (2012). ''The Silk Road: A New History''. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. . * Haw, Stephen G. (2006). ''Marco Polo's China: a Venetian in the Realm of Kublai Khan''. London & New York: Routledge. . * * * * Hoffman, Donald L. (1991). "Rusticiano da Pisa". In Lacy, Norris J. (ed.), ''The New Arthurian Encyclopedia''. New York: Garland. . * Holt, Frank L. (1989). ''Alexander the Great and Bactria: the Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia''. Leiden, New York, Copenhagen, Cologne: E. J. Brill. . * Jackson, Peter (2005), ''The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410''. Pearson Education. . * Kelly, Jack (2004). ''Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World''. Basic Books. . * Kim, Heup Young (2011). ''Asian and Oceanic Christianities in Conversation: Exploring Theological Identities at Home and in Diaspora''. Rodopi. . * Kuiper, Kathleen & editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (Aug 31, 2006).

Rabban bar Sauma: Mongol Envoy

" ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (online source). Accessed 6 September 2016. * LIVIUS.

Roxane

" ''Articles on Ancient History''. Page last modified 17 August 2015. Retrieved on 8 September 2016. * LIVIUS

''Articles of Ancient History''. 28 October 2010. Retrieved on 14 November 2010. * Lorge, Peter Allan (2008), ''The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb''. Cambridge University Press. . * Luttwak, Edward N. (2009). ''The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire''. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. . * Magill, Frank N. et al. (1998). ''The Ancient World: Dictionary of World Biography, Volume 1''. Pasadena, Chicago, London,: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, Salem Press. . * Mallory, J.P. and Victor H. Mair (2000). ''The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West''. London: Thames & Hudson. . * Mandeville, John. (1983). C.W.R.D. Moseley (trans), ''The Travels of Sir John Mandeville''. London: Penguin Books Ltd. * Milton, Osborne (2006). ''The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future''. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, revised edition, first published in 2000. . * Morgan, D.O. "Marco Polo in China-Or Not," in ''The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society'', Volume 6, Issue #2, 221–225, July 1996. * Morgan, David (2007). ''The Mongols''. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. . * Morton, William Scott and Charlton M. Lewis. (2005). ''China: Its History and Culture: Fourth Edition''. New York City: McGraw-Hill. . * * * * Moule, A. C. ''Christians in China before 1500'', 94 & 103; also Pelliot, Paul in ''T'oung-pao'' 15 (1914), pp. 630–36. * Needham, Joseph (1971). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; rpr. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd, 1986. * Needham, Joseph; et al. (1987). ''Science and Civilisation in China: Military technology: The Gunpowder Epic, Volume 5, Part 7''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . * Norris, John (2003), ''Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600'', Marlborough: The Crowood Press. * Olschki, Leonardo (1960). ''Marco Polo's Asia: an Introduction to His "Description of the World" Called "Il Milione.".'' Berkeley: University of California Press. * Pacey, Arnold (1991). ''Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-year History''. Boston: MIT Press. . * Polo, Marco; Latham, Ronald (translator) (1958). ''The Travels of Marco Polo''. New York: Penguin Books. . * Robinson, David M. "Banditry and the Subversion of State Authority in China: The Capital Region during the Middle Ming Period (1450–1525)," in ''Journal of Social History'' (Spring 2000): 527–563. * * Rossabi, Morris (2014). ''From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi''. Leiden & Boston: Brill. . *

Marco Polo Was in China: New Evidence from Currencies, Salts and Revenues

'' Leiden; Boston: Brill. . * Wills, John E., Jr. (1998). "Relations with Maritime Europeans, 1514–1662," in Mote, Frederick W. and Denis Twitchett (eds.), ''The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2'', 333–375. New York: Cambridge University Press. (Hardback edition). * Wood, Frances. (2002). ''The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia''. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. . * Xu, Shiduan (1998). "Oghul Qaimish, Empress of Mongol Emperor Dingzong," in Lily Xiao Hong Lee and Sue Wiles (eds), ''Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Tang through Ming: 618–1644'', trans. Janine Burns, London & New York: Routledge. . * Yang, Juping. “Hellenistic Information in China.” ''CHS Research Bulletin'' 2, no. 2 (2014). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:YangJ.Hellenistic_Information_in_China.2014. * Ye, Yiliang (2010). "Introductory Essay: Outline of the Political Relations between Iran and China," in Ralph Kauz (ed.), ''Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea''. Weisbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. . * Young, Gary K. (2001). ''Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC - AD 305''. London & New York: Routledge, . * * Yu, Taishan (June 2010). "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), ''Sino-Platonic Papers''. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. * Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in ''The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220'', 377–462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 377–388, 391, . * * * Zhao, Feng (2004). "Wall hanging with centaur and warrior," in James C.Y. Watt, John P. O'Neill et al. (eds) and trans. Ching-Jung Chen et al., ''China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 A.D.''. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, Metropolitan Museum of Art. .

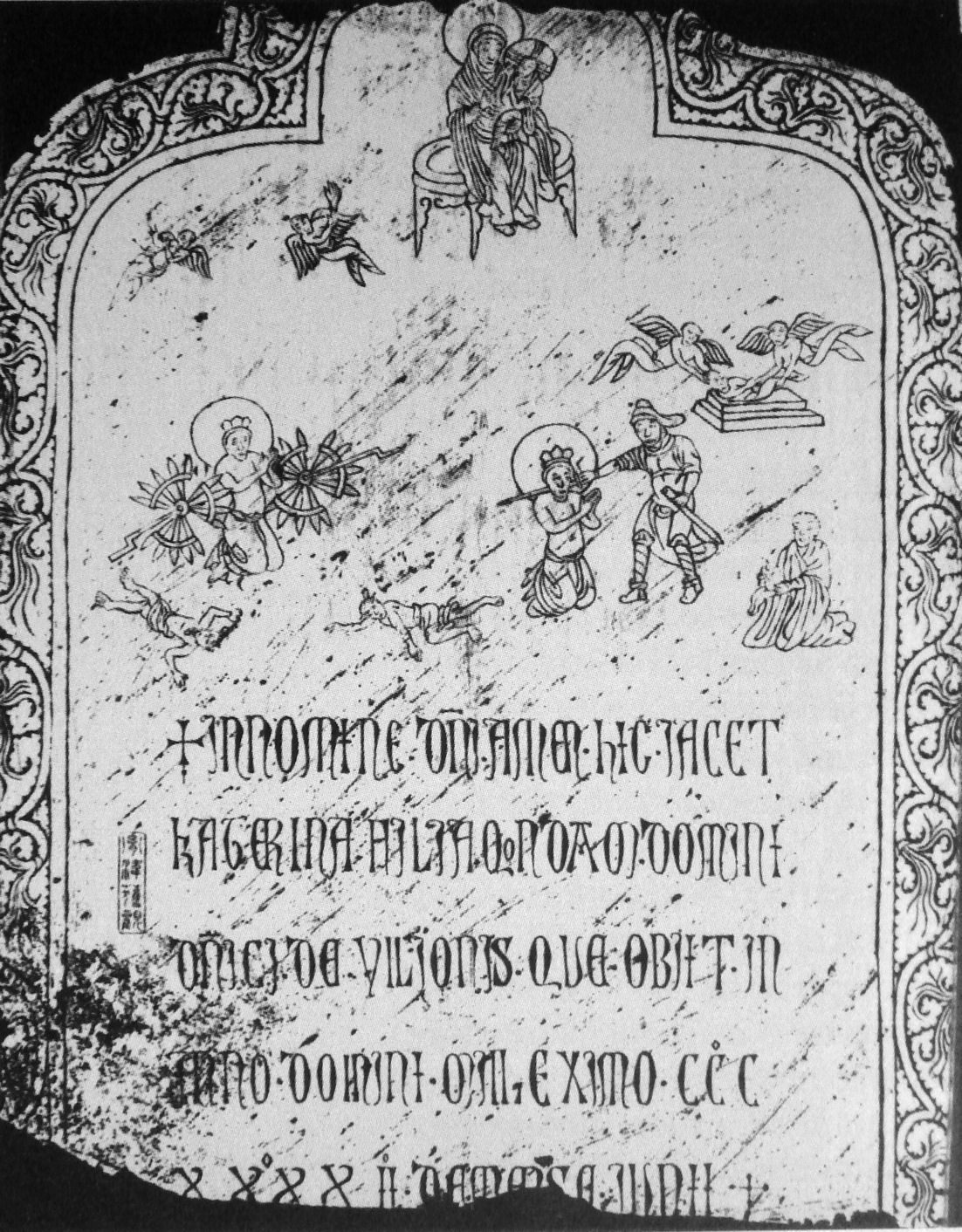

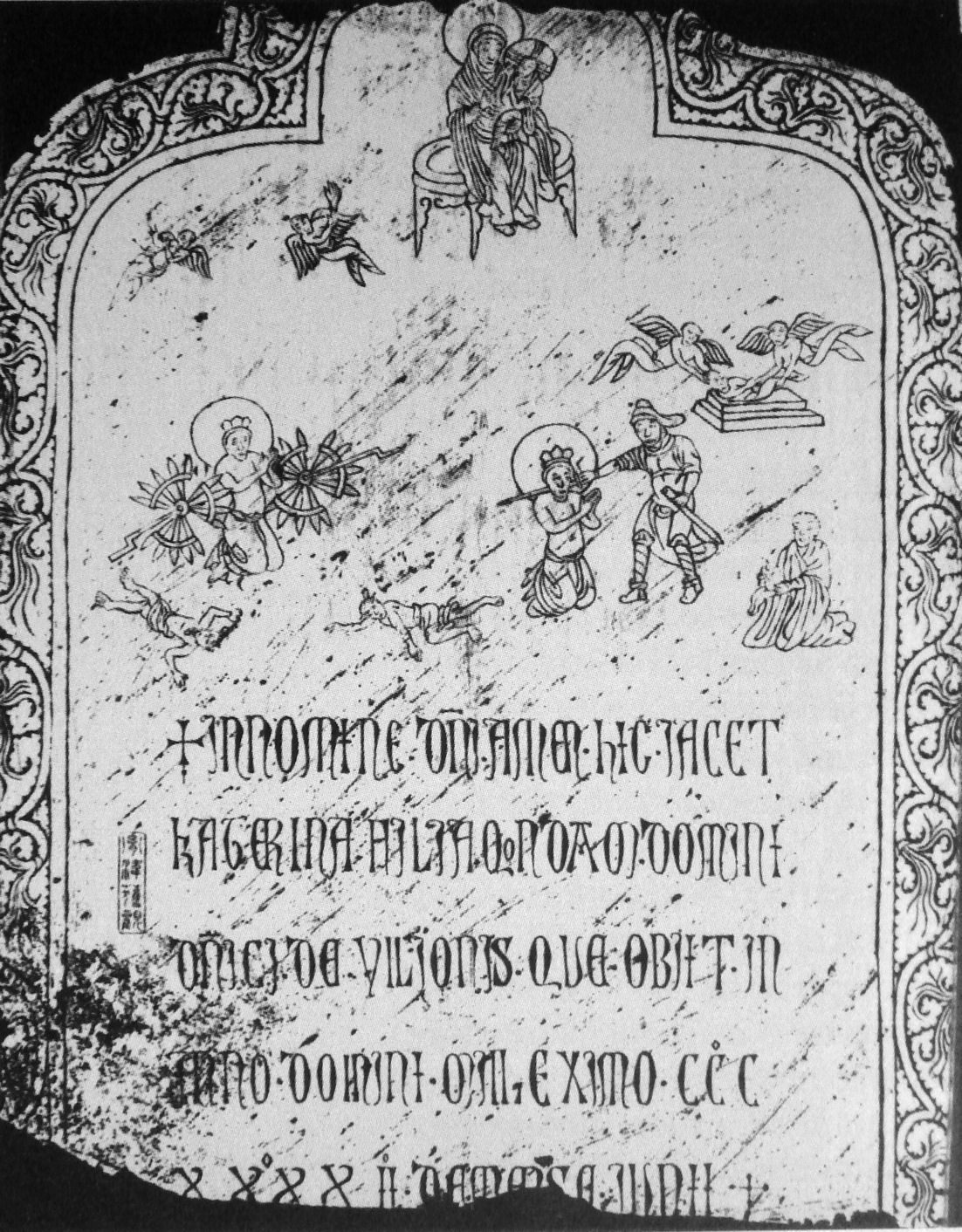

Franciscans in ChinaPrincely Gifts & Papal Treasures: The Franciscan Mission to China & Its Influence on the Art of the West, 1250–1350

{{DEFAULTSORT:Europeans In Medieval China European diaspora in China History of Imperial China History of Europe Yuan dynasty Ming dynasty Foreign relations of Imperial China Medieval international relations

Fergana Valley

The Fergana Valley (; ; ) in Central Asia lies mainly in eastern Uzbekistan, but also extends into southern Kyrgyzstan and northern Tajikistan.

Divided into three republics of the former Soviet Union, the valley is ethnically diverse and in the ...

, with Alexandria Eschate as its capital, and the "Daxia

Daxia, Ta-Hsia, or Ta-Hia (; literally: 'Great Xia') was apparently the name given in antiquity by the Han Chinese to Tukhara or Tokhara: the main part of Bactria, in what is now northern Afghanistan, and parts of southern Tajikistan and Uzbek ...

" of Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

, in what is now Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Later the Han captured Dayuan in the Han-Dayuan war

The War of the Heavenly Horses () or the Han–Dayuan War () was a military conflict fought in 104 BC and 102 BC between the Chinese Han dynasty and the Saka-ruled (Scythian) Greco-Bactrian kingdom known to the Chinese as Dayuan, in the Fergha ...

. It has also been suggested that the Terracotta Army

The Terracotta Army is a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China. It is a form of funerary art buried with the emperor in 210–209 BCE with the purpose of protecting the emperor in ...

(sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang (, ; 259–210 BC) was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first emperor of a unified China. Rather than maintain the title of "king" ( ''wáng'') borne by the previous Shang and Zhou rulers, he ruled as the First Emperor ( ...

, first Emperor of China; dated to ~210 BCE), in the Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by #Name, other names, is the list of capitals in China, capital of Shaanxi, Shaanxi Province. A Sub-provincial division#Sub-provincial municipalities, sub-provincial city o ...

region of Shaanxi Province

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), Ningx ...

, might be inspired by Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

sculptural art, a hypothesis that has caused some controversy.

At the cemetery in Sampul (Shanpula; 山普拉), ~14 km from Khotan

Hotan (also known as Gosthana, Gaustana, Godana, Godaniya, Khotan, Hetian, Hotien) is a major oasis town in southwestern Xinjiang, an autonomous region in Western China. The city proper of Hotan broke off from the larger Hotan County to become ...

(now in Lop County

Lop, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency County (, Uyghur: ), also Luopu, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (from Mandarin Chinese), is a county in Hotan Prefecture, in the southwest of the Xinjiang Uyghu ...

, Hotan Prefecture

Hotan PrefectureThe official spelling is "Hotan" according to (also known as Gosthana, Gaustana, Godana, Godaniya, Khotan, Hetian, Hotien) is located in the Tarim Basin region of southwestern Xinjiang, China, bordering the Tibet Autonomous Region ...

, Xinjiang), where the aforementioned Sampul tapestry was found, the local inhabitants buried their dead there from roughly 217 BC to 283 AD. Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

analysis of the human remains has revealed genetic affinities to peoples from the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

, specifically a maternal

]

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of gestat ...

lineage linked to Ossetians

The Ossetians or Ossetes (, ; os, ир, ирæттæ / дигорӕ, дигорӕнттӕ, translit= ir, irættæ / digoræ, digorænttæ, label=Ossetic) are an Iranian ethnic group who are indigenous to Ossetia, a region situated across the no ...

and Iranians, as well as an Eastern-Mediterranean paternal

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

lineage.Chengzhi Xie et al.,Mitochondrial DNA analysis of ancient Sampula population in Xinjiang

" in ''Progress in Natural Science'', vol. 17, (August 2007), pp 927–33.Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), ''Sino-Platonic Papers'', No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 27 & footnote #46, ISSN 2157-9687. Seeming to confirm this link, from historical accounts it is known that

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, who married a Sogdia

Sogdia (Sogdian language, Sogdian: ) or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also ...

n woman from Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

named Roxana

Roxana (c. 340 BC – 310 BC, grc, Ῥωξάνη; Old Iranian: ''*Raṷxšnā-'' "shining, radiant, brilliant"; sometimes Roxanne, Roxanna, Rukhsana, Roxandra and Roxane) was a Sogdian or a Bactrian princess whom Alexander the Great married a ...

,Livius.org.Roxane

" ''Articles on Ancient History''. Page last modified 17 August 2015. Retrieved on 8 September 2016.Strachan, Edward and Roy Bolton (2008), ''Russia and Europe in the Nineteenth Century'', London: Sphinx Fine Art, p. 87, . encouraged his soldiers and generals to marry local women; consequentially the later kings of the

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

and Greco-Bactrian Kingdom had a mixed Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

-Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

ethnic background.

Ancient Romans

Beginning in the age ofAugustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

(r. 27 BC – 14 AD), the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, including authors such as Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

, mentioned contacts with the ''Seres

Seres are the people of Serica, one of the easternmost countries of Asia known to the ancient Greeks and Romans.

Seres may also refer to:

People

*

*

*

Brands and enterprises

*

See also

* Celes (disambiguation) Celes may refer to:

* ...

'', whom they identified as the producers of silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

from distant East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

and could have been the Chinese or even any number of middlemen of various ethnic backgrounds along the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

of Central Asia and Northwest China

Northwest China () is a statistical region of China which includes the autonomous regions of Xinjiang and Ningxia and the provinces of Shaanxi, Gansu and Qinghai. It has an area of 3,107,900 km2.

The region is characterized by a (semi-)arid con ...

. The Eastern-Han era Chinese general Ban Chao

Ban Chao (; 32–102 CE), courtesy name Zhongsheng, was a Chinese diplomat, explorer, and military general of the Eastern Han Dynasty. He was born in Fufeng, now Xianyang, Shaanxi. Three of his family members—father Ban Biao, elder brother ...

, Protector General of the Western Regions

The Protectorate of the Western Regions () was an imperial administration (a protectorate) of Han China in the Western Regions.

The "Western Regions" referred to areas west of Yumen Pass, especially the Tarim Basin. These areas would later be ...

, explored Central Asia and in 97 AD dispatched his envoys Gan Ying

Gan Ying (; fl. 90s CE) was a Chinese diplomat, explorer, and military official who was sent on a mission to the Roman Empire in 97 CE by the Chinese military general Ban Chao.

Gan Ying did not reach Rome, only traveling to as far as the "west ...

to Daqin

Daqin (; alternative transliterations include Tachin, Tai-Ch'in) is the ancient Chinese name for the Roman Empire or, depending on context, the Near East, especially Syria. It literally means "great Qin"; Qin () being the name of the founding dyn ...

(i.e. the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

). Gan was dissuaded by Parthian authorities from venturing further than the "west coast" (possibly the Eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to communi ...

) although he wrote a detailed report about the Roman Empire, its cities, postal network and consular system of government, and presented this to the Han court.

Subsequently, there was a series of Roman embassies in China lasting from the 2nd to 3rd centuries AD, as recorded in Chinese sources. In 166 AD the ''Book of Later Han

The ''Book of the Later Han'', also known as the ''History of the Later Han'' and by its Chinese name ''Hou Hanshu'' (), is one of the Twenty-Four Histories and covers the history of the Han dynasty from 6 to 189 CE, a period known as the Later ...

'' records that Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

reached China from the maritime south and presented gifts to the court of Emperor Huan of Han

Emperor Huan of Han (; 132 – 25 January 168) was the 27th emperor of the Han dynasty after he was enthroned by the Empress Dowager and her brother Liang Ji on 1 August 146. He was a great-grandson of Emperor Zhang. He was the 11th Emperor of ...

(r. 146–168 AD), claiming they represented Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

(''Andun'' 安敦, r. 161–180 AD). de Crespigny, Rafe. (2007). ''A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD)''. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, p. 600, . There is speculation that they were Roman merchants instead of official diplomats.

At the very least, archaeological evidence supports the claim in the ''Weilüe

The ''Weilüe'' () was a Chinese historical text written by Yu Huan between 239 and 265. Yu Huan was an official in the state of Cao Wei (220–265) during the Three Kingdoms period (220–280). Although not a formal historian, Yu Huan has been h ...

'' and ''Book of Liang

The ''Book of Liang'' (''Liáng Shū''), was compiled under Yao Silian and completed in 635. Yao heavily relied on an original manuscript by his father Yao Cha, which has not independently survived, although Yao Cha's comments are quoted in seve ...

'' that Roman merchants were active in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, if not the claim of their embassies arriving in China through Jiaozhi

Jiaozhi (standard Chinese, pinyin: ''Jiāozhǐ''), or Giao Chỉ (Vietnamese), was a historical region ruled by various Chinese dynasties, corresponding to present-day northern Vietnam. The kingdom of Nanyue (204–111 BC) set up the Jiaozhi Co ...

, the Chinese-controlled province of northern Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

. Roman golden medal

A medal or medallion is a small portable artistic object, a thin disc, normally of metal, carrying a design, usually on both sides. They typically have a commemorative purpose of some kind, and many are presented as awards. They may be int ...

lions from the reigns of Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius (Latin: ''Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius''; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatoria ...

and his adopted son Marcus Aurelius have been found in Oc Eo (near Ho Chi Minh City

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

), a territory that belonged to the Kingdom of Funan

Funan (; km, ហ៊្វូណន, ; vi, Phù Nam, Chữ Hán: ) was the name given by Chinese cartographers, geographers and writers to an ancient Indianized state—or, rather a loose network of states ''(Mandala)''—located in mainla ...

bordering Jiaozhi.Gary K. Young (2001), Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC - AD 305, London & New York: Routledge, , pp 29–30. Suggestive of even earlier activity is a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

-era Roman glass

Roman glass objects have been recovered across the Roman empire, Roman Empire in domestic, industrial and funerary contexts. Glass was used primarily for the production of vessels, although mosaic tiles and window glass were also produced. Roman g ...

bowl unearthed from a Western Han

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

tomb of Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

(on the shores of the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by the shores of South China (hence the name), in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Phil ...

) dated to the early 1st century BC, in addition to ancient Mediterranean goods found in Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

, and Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

. The Greco-Roman geographer Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

wrote in his Antonine-era ''Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

'' that beyond the Golden Chersonese (Malay Peninsula

The Malay Peninsula (Malay: ''Semenanjung Tanah Melayu'') is a peninsula in Mainland Southeast Asia. The landmass runs approximately north–south, and at its terminus, it is the southernmost point of the Asian continental mainland. The area ...

) was a port city called Kattigara

Cattigara is the name of a major port city located on the Magnus Sinus described by various antiquity sources. Modern scholars have linked Cattigara to the archaeological site of Óc Eo in present-day Vietnam.

Ptolemy's description

Cattigara w ...

discovered by a Greek sailor named Alexander, a site Ferdinand von Richthofen assumed was Chinese-controlled Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi is ...

, but given the archaeological evidence could have been Oc Eo. Roman coins have been found in China, but far fewer than in India.Warwick Ball (2016), ''Rome in the East: Transformation of an Empire'', 2nd edition, London & New York: Routledge, , p. 154.

It is possible that a group of Greek acrobatic performers, who claimed to be from a place " west of the seas" (i.e. Roman Egypt

, conventional_long_name = Roman Egypt

, common_name = Egypt

, subdivision = Province

, nation = the Roman Empire

, era = Late antiquity

, capital = Alexandria

, title_leader = Praefectus Augustalis

, image_map = Roman E ...

, which the ''Book of Later Han'' related to the "Daqin" empire), were presented by a king of Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

to Emperor An of Han

Emperor An of Han (; 94 – 30 April 125) was an emperor of the Chinese Han Dynasty and the sixth emperor of the Eastern Han, ruling from 106 to 125. He was the grandson of Emperor Zhang.

When her infant stepson Emperor Shang succeeded ...

in 120 AD. It is known that in both the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conque ...

and Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire ( grc, Βασιλεία Κοσσανῶν; xbc, Κυϸανο, ; sa, कुषाण वंश; Brahmi: , '; BHS: ; xpr, 𐭊𐭅𐭔𐭍 𐭇𐭔𐭕𐭓, ; zh, 貴霜 ) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, i ...

of Asia, ethnic Greeks continued to be employed as entertainers such as musicians and athletes who engaged in athletic competitions.

Byzantine Empire

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

Greek historian Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gener ...

stated that two Nestorian Christian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian N ...

monks eventually uncovered how silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

was made. From this revelation, monks were sent by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

(ruled 527–565) as spies on the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

from Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

to China and back to steal the silkworm eggs. This resulted in silk production in the Mediterranean, particularly in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

, in northern Greece,"Silk Road", LIVIUS Articles of Ancient History. 28 October 2010. Retrieved on 14 November 2010. and giving the Byzantine Empire a monopoly on silk production in medieval Europe until the loss of its territories in Southern Italy. The Byzantine historian

Theophylact Simocatta

Theophylact Simocatta (Byzantine Greek: Θεοφύλακτος Σιμοκάτ(τ)ης ''Theophýlaktos Simokát(t)ēs''; la, Theophylactus Simocatta) was an early seventh-century Byzantine Empire, Byzantine historiographer, arguably ranking as th ...

, writing during the reign of Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was List of Byzantine emperors, Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the Exa ...

(r. 610–641), relayed information about China's geography, its capital city ''Khubdan'' (Old Turkic

Old Turkic (also East Old Turkic, Orkhon Turkic language, Old Uyghur) is the earliest attested form of the Turkic languages, found in Göktürks, Göktürk and Uyghur Khaganate inscriptions dating from about the eighth to the 13th century. It ...

: ''Khumdan'', i.e. Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin Shi ...

), its current ruler ''Taisson'' whose name meant "Son of Heaven

Son of Heaven, or ''Tianzi'' (), was the sacred monarchical title of the Chinese sovereign. It originated with the Zhou dynasty and was founded on the political and spiritual doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven. Since the Qin dynasty, the secula ...

" (Chinese: 天子 ''Tianzi'', although this could be derived from the name of Emperor Taizong of Tang

Emperor Taizong of Tang (28January 59810July 649), previously Prince of Qin, personal name Li Shimin, was the second emperor of the Tang dynasty of China, ruling from 626 to 649. He is traditionally regarded as a co-founder of the dynasty ...

), and correctly pointed to its reunification by the Sui dynasty

The Sui dynasty (, ) was a short-lived imperial dynasty of China that lasted from 581 to 618. The Sui unified the Northern and Southern dynasties, thus ending the long period of division following the fall of the Western Jin dynasty, and layi ...

(581–618) as occurring during the reign of Maurice Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

* Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and ...

, noting that China had previously been divided politically along the Yangzi River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

by two warring nations.

The Chinese ''Old Book of Tang

The ''Old Book of Tang'', or simply the ''Book of Tang'', is the first classic historical work about the Tang dynasty, comprising 200 chapters, and is one of the Twenty-Four Histories. Originally compiled during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdo ...

'' and ''New Book of Tang

The ''New Book of Tang'', generally translated as the "New History of the Tang" or "New Tang History", is a work of official history covering the Tang dynasty in ten volumes and 225 chapters. The work was compiled by a team of scholars of the So ...

'' mention several embassies made by ''Fu lin'' (拂菻; i.e. Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

), which they equated with Daqin

Daqin (; alternative transliterations include Tachin, Tai-Ch'in) is the ancient Chinese name for the Roman Empire or, depending on context, the Near East, especially Syria. It literally means "great Qin"; Qin () being the name of the founding dyn ...

(i.e. the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

), beginning in 643 with an embassy sent by the king ''Boduoli'' (波多力, i.e. Constans II Pogonatos) to Emperor Taizong of Tang

Tang or TANG most often refers to:

* Tang dynasty

* Tang (drink mix)

Tang or TANG may also refer to:

Chinese states and dynasties

* Jin (Chinese state) (11th century – 376 BC), a state during the Spring and Autumn period, called Tang (唐) b ...

, bearing gifts such as red glass. These histories also provided cursory descriptions of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, its walls, and how it was besieged by ''Da shi'' (大食; the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

) and their commander "Mo-yi" (摩拽; i.e. Muawiyah I

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

, governor of Syria before becoming caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

), who forced them to pay tribute. From Chinese records it is known that Michael VII Doukas

Michael VII Doukas or Ducas ( gr, Μιχαήλ Δούκας), nicknamed Parapinakes ( gr, Παραπινάκης, lit. "minus a quarter", with reference to the devaluation of the Byzantine currency under his rule), was the senior Byzantine e ...

(Mie li sha ling kai sa 滅力沙靈改撒) of ''Fu lin'' dispatched a diplomatic mission to China's Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

that arrived in 1081, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong of Song

Emperor Shenzong of Song (25 May 1048 – 1 April 1085), personal name Zhao Xu, was the sixth emperor of the Song dynasty of China. His original personal name was Zhao Zhongzhen but he changed it to "Zhao Xu" after his coronation. He reigned fr ...

. Some Chinese during the Song period showed interest in countries to the west, such as the early 13th-century Quanzhou

Quanzhou, postal map romanization, alternatively known as Chinchew, is a prefecture-level city, prefecture-level port city on the north bank of the Jin River, beside the Taiwan Strait in southern Fujian, China. It is Fujian's largest metrop ...

customs inspector Zhao Rugua Zhao Rukuo (; 1170–1231), also read as Zhao Rugua, or misread as Zhao Rushi, was a Chinese historian and politician during the Song dynasty. He wrote a two-volume book titled ''Zhu Fan Zhi''. The book deals with the world known to the Chinese in t ...

, who described the ancient Lighthouse of Alexandria

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, sometimes called the Pharos of Alexandria (; Ancient Greek: ὁ Φάρος τῆς Ἀλεξανδρείας, contemporary Koine ), was a lighthouse built by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, during the re ...

in his ''Zhu fan zhi

''Zhu Fan Zhi'' (), variously translated as '' A Description of Barbarian Nations'', ''Records of Foreign People'', or other similar titles, is a 13th-century Song Dynasty work by Zhao Rukuo. The work is a collection of descriptions of countrie ...

''.

Merchants

ibn Khordadbeh

Abu'l-Qasim Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah ibn Khordadbeh ( ar, ابوالقاسم عبیدالله ابن خرداذبه; 820/825–913), commonly known as Ibn Khordadbeh (also spelled Ibn Khurradadhbih; ), was a high-ranking Persian bureaucrat and ...

, China was a destination for Radhanite Jews buying boys, female slaves and eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millennium ...

s from Europe. During the subsequent Song period there was also a community of Kaifeng Jews

The Kaifeng Jews ( zh, t=開封猶太族, p=Kāifēng Yóutàizú; he, יהדות קאיפנג ''Yahădūt Qāʾyfeng'') are members of a small community of descendants of Chinese Jews in Kaifeng, in the Henan province of China. In the early ...

in China. The Spaniard, Benjamin of Tudela

Benjamin of Tudela ( he, בִּנְיָמִין מִטּוּדֶלָה, ; ar, بنيامين التطيلي ''Binyamin al-Tutayli''; Tudela, Kingdom of Navarre, 1130 Castile, 1173) was a medieval Jewish traveler who visited Europe, Asia, an ...

(from Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

) was a 12th-century Jewish traveler whose ''Travels of Benjamin'' recorded vivid descriptions of Europe, Asia, and Africa, preceding those of Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

by a hundred years.

Polo, a 13th-century merchant from the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

, describes his travels to Yuan-dynasty China and the court of Mongol ruler Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of th ...

, along with the preceding journeys made by Niccolò and Maffeo Polo, his father and uncle, respectively, in his ''Travels of Marco Polo

''Book of the Marvels of the World'' (Italian: , lit. 'The Million', deriving from Polo's nickname "Emilione"), in English commonly called ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', is a 13th-century travelogue written down by Rustichello da Pisa from sto ...

''. Polo related this account to Rustichello da Pisa

Rustichello da Pisa, also known as Rusticiano (fl. late 13th century), was an Italian Romance (heroic literature), romance writer in Franco-Italian language. He is best known for co-writing Marco Polo's autobiography, ''The Travels of Marco Polo' ...

around 1298 while they shared a Genoese prison cell following their capture in battle. In his return trip to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

from China (setting out from the port at Quanzhou

Quanzhou, postal map romanization, alternatively known as Chinchew, is a prefecture-level city, prefecture-level port city on the north bank of the Jin River, beside the Taiwan Strait in southern Fujian, China. It is Fujian's largest metrop ...

in 1291), Marco Polo said that he accompanied the Mongol princess Kököchin

Kököchin, also Kökejin, Kūkājīn, Cocacin or Cozotine ( Mn: , Ch: ), was a 13th-century princess of the Mongol-led Chinese Yuan dynasty, belonging to the Mongol Bayaut tribe. In 1291, she was betrothed to the Ilkhanate khan Arghun by the Y ...

in her intended marriage to Arghun

Arghun Khan (Mongolian Cyrillic: ''Аргун хан''; Traditional Mongolian: ; c. 1258 – 10 March 1291) was the fourth ruler of the Mongol empire's Ilkhanate, from 1284 to 1291. He was the son of Abaqa Khan, and like his father, was a dev ...

, ruler of the Mongol Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm, ...

, but she instead married his son Ghazan

Mahmud Ghazan (5 November 1271 – 11 May 1304) (, Ghazan Khan, sometimes archaically spelled as Casanus by the Westerners) was the seventh ruler of the Mongol Empire's Ilkhanate division in modern-day Iran from 1295 to 1304. He was the son of A ...

following the former's sudden death. Although Marco Polo's presence is omitted entirely, his story is confirmed by the 14th-century Persian historian Rashid-al-Din Hamadani

Rashīd al-Dīn Ṭabīb ( fa, رشیدالدین طبیب; 1247–1318; also known as Rashīd al-Dīn Faḍlullāh Hamadānī, fa, links=no, رشیدالدین فضلالله همدانی) was a statesman, historian and physician in Ilk ...

in his ''Jami' al-tawarikh

The ''Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh'' (Persian/Arabic: , ) is a work of literature and history, produced in the Mongol Ilkhanate. Written by Rashid al-Din Hamadani (1247–1318 AD) at the start of the 14th century, the breadth of coverage of the work h ...

''.

Marco Polo accurately described geographical features of China such as the Grand Canal. His detailed and accurate descriptions of salt production

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quanti ...

confirm that he had actually been in China. Marco described salt wells and hills where salt could be mined, probably in Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in Southwest China, the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is ...

, and reported that in the mountains "these rascals ... have none of the Great Khan's paper money, but use salt instead ... They have salt which they boil and set in a mold ..." Polo also remarked how the Chinese burned paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, rags, grasses or other vegetable sources in water, draining the water through fine mesh leaving the fibre evenly distributed ...

effigies

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

shaped as male and female servants, camel

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. C ...

s, horses, suits of clothing and armor while cremating the dead during funerary rites

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect th ...

.

When visiting Zhenjiang

Zhenjiang, alternately romanized as Chinkiang, is a prefecture-level city in Jiangsu Province, China. It lies on the southern bank of the Yangtze River near its intersection with the Grand Canal. It is opposite Yangzhou (to its north) and b ...

in Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, Postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an Eastern China, eastern coastal Provinces of the People's Republic of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is o ...

, China, Marco Polo noted that Christian church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym fo ...

es had been built there. His claim is confirmed by a Chinese text of the 14th century explaining how a Sogdia

Sogdia (Sogdian language, Sogdian: ) or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also ...

n named Mar-Sargis from Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top:Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zinda, ...

founded six Nestorian Christian churches there in addition to one in Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the province, sitting at the head of Hangzhou Bay, whi ...

during the second half of the 13th century.Emmerick, R. E. (2003) "Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs", in Ehsan Yarshater, ''The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p 275. Nestorian Christianity had existed in China earlier during the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

(618–907 AD) when a Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

n monk named Alopen

Alopen (, ; also "Aleben", "Aluoben", "Olopen," "Olopan," or "Olopuen") is the first recorded Assyrian Christian missionary to have reached China, during the Tang dynasty. He was a missionary from the Church of the East (also known as the "Nestori ...

(Chinese: ''Āluósī''; 阿羅本; 阿羅斯) came to the capital Chang'an in 653 to proselytize

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between ''evangelism'' or '' Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invol ...

, as described in a dual Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

and Syriac language

The Syriac language (; syc, / '), also known as Syriac Aramaic (''Syrian Aramaic'', ''Syro-Aramaic'') and Classical Syriac ܠܫܢܐ ܥܬܝܩܐ (in its literary and liturgical form), is an Aramaic language, Aramaic dialect that emerged during ...

inscription from Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin Shi ...

(modern Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by #Name, other names, is the list of capitals in China, capital of Shaanxi, Shaanxi Province. A Sub-provincial division#Sub-provincial municipalities, sub-provincial city o ...

) dated to the year 781.

Others were soon to follow. The Italian Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related Mendicant orders, mendicant Christianity, Christian Catholic religious order, religious orders within the Catholic Church. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi, these orders include t ...

friar John of Montecorvino

John of Montecorvino or Giovanni da Montecorvino in Italian (1247 – 1328) was an Italian Franciscan missionary, traveller and statesman, founder of the earliest Latin Catholic missions in India and China, and archbishop of Peking. He convert ...

took a journey starting in 1291, setting out from Tabriz to Ormus

The Kingdom of Ormus (also known as Hormoz; fa, هرمز; pt, Ormuz) was located in the eastern side of the Persian Gulf and extended as far as Bahrain in the west at its zenith. The Kingdom was established in 11th century initially as a depe ...

, sailing from there to China while accompanied by the Italian merchant Pietro de Lucalongo. While Montecorvino became a bishop in Khanbaliq (Beijing), his friend Lucalongo continued to serve as a merchant there and donated a large amount of money to maintain the local Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Marco Polo mentioned the heavy presence of Genoese Italians at Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the List of largest cities of Iran, sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quri Chay, Quru River valley in Iran's historic Aze ...

(modern Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

), a city that Marco returned to from China via the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz ( fa, تنگه هرمز ''Tangeh-ye Hormoz'' ar, مَضيق هُرمُز ''Maḍīq Hurmuz'') is a strait between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. It provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the ...

in 1293–1294. John Mandeville

Sir John Mandeville is the supposed author of ''The Travels of Sir John Mandeville'', a travel memoir which first circulated between 1357 and 1371. The earliest-surviving text is in French.

By aid of translations into many other languages, the ...

, a mid-14th-century author and alleged Englishman from St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

, claimed to have lived in China and even served at the Mongol khan's court. However, certain parts of his accounts are considered dubious by modern scholars, with some conjecturing that he simply concocted his stories by using written accounts of China penned by other authors such as Odoric of Pordenone

Odoric of Pordenone, OFM (1286–1331), also known as Odorico Mattiussi/Mattiuzzi, Odoricus of Friuli or Orderic of Pordenone, was an Italian late-medieval Franciscan friar and missionary explorer. He traveled through India, the Greater Sunda Is ...

.

Chinese poems

Chinese poetry is poetry written, spoken, or chanted in the Chinese language. While this last term comprises Classical Chinese, Standard Chinese, Mandarin Chinese, Yue Chinese, and other historical and vernacular forms of the language, its poetry ...

and paintings