European Common Market on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the

Another crisis was triggered in regard to proposals for the financing of the Common Agricultural Policy, which came into force in 1962. The transitional period whereby decisions were made by unanimity had come to an end, and majority-voting in the council had taken effect. Then- French President Charles de Gaulle's opposition to supranationalism and fear of the other members challenging the CAP led to an "empty chair policy" whereby French representatives were withdrawn from the European institutions until the French veto was reinstated. Eventually, a compromise was reached with the Luxembourg compromise on 29 January 1966 whereby a gentlemen's agreement permitted members to use a veto on areas of national interest.

On 1 July 1967 when the Merger Treaty came into operation, combining the institutions of the ECSC and Euratom into that of the EEC, they already shared a Parliamentary Assembly and

Another crisis was triggered in regard to proposals for the financing of the Common Agricultural Policy, which came into force in 1962. The transitional period whereby decisions were made by unanimity had come to an end, and majority-voting in the council had taken effect. Then- French President Charles de Gaulle's opposition to supranationalism and fear of the other members challenging the CAP led to an "empty chair policy" whereby French representatives were withdrawn from the European institutions until the French veto was reinstated. Eventually, a compromise was reached with the Luxembourg compromise on 29 January 1966 whereby a gentlemen's agreement permitted members to use a veto on areas of national interest.

On 1 July 1967 when the Merger Treaty came into operation, combining the institutions of the ECSC and Euratom into that of the EEC, they already shared a Parliamentary Assembly and

Folketingets EU-Oplysning Both Amsterdam and the Treaty of Nice also extended codecision procedure to nearly all policy areas, giving Parliament equal power to the Council in the Community. In 2002, the Treaty of Paris which established the ECSC expired, having reached its 50-year limit (as the first treaty, it was the only one with a limit). No attempt was made to renew its mandate; instead, the Treaty of Nice transferred certain of its elements to the

Member states are represented in some form in each institution. The Council is also composed of one national minister who represents their national government. Each state also has a right to one European Commissioner each, although in the European Commission they are not supposed to represent their national interest but that of the Community. Prior to 2004, the larger members (France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom) have had two Commissioners. In the

Member states are represented in some form in each institution. The Council is also composed of one national minister who represents their national government. Each state also has a right to one European Commissioner each, although in the European Commission they are not supposed to represent their national interest but that of the Community. Prior to 2004, the larger members (France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom) have had two Commissioners. In the

The EEC inherited some of the Institutions of the ECSC in that the Common Assembly and Court of Justice of the ECSC had their authority extended to the EEC and Euratom in the same role. However the EEC, and Euratom, had different executive bodies to the ECSC. In place of the ECSC's Council of Ministers was the Council of the European Economic Community, and in place of the High Authority was the Commission of the European Communities.

There was greater difference between these than name: the French government of the day had grown suspicious of the supranational power of the High Authority and sought to curb its powers in favour of the intergovernmental style Council. Hence the Council had a greater executive role in the running of the EEC than was the situation in the ECSC. By virtue of the Merger Treaty in 1967, the executives of the ECSC and Euratom were merged with that of the EEC, creating a single institutional structure governing the three separate Communities. From here on, the term ''European Communities'' were used for the institutions (for example, from ''Commission of the European Economic Community'' to the ''Commission of the European Communities'').

The EEC inherited some of the Institutions of the ECSC in that the Common Assembly and Court of Justice of the ECSC had their authority extended to the EEC and Euratom in the same role. However the EEC, and Euratom, had different executive bodies to the ECSC. In place of the ECSC's Council of Ministers was the Council of the European Economic Community, and in place of the High Authority was the Commission of the European Communities.

There was greater difference between these than name: the French government of the day had grown suspicious of the supranational power of the High Authority and sought to curb its powers in favour of the intergovernmental style Council. Hence the Council had a greater executive role in the running of the EEC than was the situation in the ECSC. By virtue of the Merger Treaty in 1967, the executives of the ECSC and Euratom were merged with that of the EEC, creating a single institutional structure governing the three separate Communities. From here on, the term ''European Communities'' were used for the institutions (for example, from ''Commission of the European Economic Community'' to the ''Commission of the European Communities'').

The Council of the European Communities was a body holding legislative and executive powers and was thus the main decision making body of the Community. Its Presidency rotated between the member states every six months and it is related to the European Council, which was an informal gathering of national leaders (started in 1961) on the same basis as the Council.

The Council was composed of one national

The Council of the European Communities was a body holding legislative and executive powers and was thus the main decision making body of the Community. Its Presidency rotated between the member states every six months and it is related to the European Council, which was an informal gathering of national leaders (started in 1961) on the same basis as the Council.

The Council was composed of one national

Under the Community, the

Under the Community, the

Books

* Ludlow, N. Piers (2006). ''The European Community and the Crises of the 1960s. Negotiating the Gaullist Challenge'

The European Community and the Crises of the 1960s: Negotiating the Gaullist Challenge

* Warlouzet, Laurent (2018). ''Governing Europe in a Globalizing World. Neoliberalism and its Alternatives following the 1973 Oil Crisis'

Governing Europe in a Globalizing World: Neoliberalism and its Alternatives following the 1973 Oil Crisis

EEC on the UK Parliament website

Documents

of the European Economic Community are consultable at th

Historical Archives of the EU

in Florence

on CVCE website

History of the Rome Treaties

on CVCE website

* ttp://ec.europa.eu/ecip/index_en.htm European Customs Information Portal (ECIP)br>The history of the European Union

{{Authority control History of the European Union Organizations established in 1958 Organizations disestablished in 1993 Former international organizations 1958 establishments in Europe 1993 disestablishments in Europe States and territories established in 1958

Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was sig ...

of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbon Treaty. aiming to foster economic integration among its member states. It was subsequently renamed the European Community (EC) upon becoming integrated into the first pillar of the newly formed European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been ...

in 1993. In the popular language, however, the singular ''European Community'' was sometimes inaccuratelly used in the wider sense of the plural '' European Communities'', in spite of the latter designation covering all the three constituent entities of the first pillar.

In 2009, the EC formally ceased to exist and its institutions were directly absorbed by the EU. This made the Union the formal successor institution of the Community.

The Community's initial aim was to bring about economic integration, including a common market and customs union, among its six founding members: Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small land ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

. It gained a common set of institutions along with the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) as one of the European Communities under the 1965 Merger Treaty (Treaty of Brussels). In 1993 a complete single market was achieved, known as the internal market, which allowed for the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people within the EEC. In 1994 the internal market was formalised by the EEA agreement. This agreement also extended the internal market to include most of the member states of the European Free Trade Association, forming the European Economic Area, which encompasses 15 countries.

Upon the entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty in 1993, the EEC was renamed the European Community to reflect that it covered a wider range than economic policy. This was also when the three European Communities, including the EC, were collectively made to constitute the first of the three pillars of the European Union, which the treaty also founded. The EC existed in this form until it was abolished by the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon, which incorporated the EC's institutions into the EU's wider framework and provided that the EU would "replace and succeed the European Community".

The EEC was also known as the European Common Market in the English-speaking countries and sometimes referred to as the European Community even before it was officially renamed as such in 1993.

History

Background

In April 1951, the Treaty of Paris was signed, creating the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). This was an international community based on supranationalism and international law, designed to help the economy of Europe and prevent future war by integrating itsmembers

Member may refer to:

* Military jury, referred to as "Members" in military jargon

* Element (mathematics), an object that belongs to a mathematical set

* In object-oriented programming, a member of a class

** Field (computer science), entries in ...

.

With the aim of creating a federal Europe two further communities were proposed: a European Defence Community and a European Political Community European Political Community may refer to:

* European Political Community (1952), a failed proposal with a draft treaty to establish an entity in the 1950s

* European Political Community (2022), a forum of European heads of state and government est ...

. While the treaty for the latter was being drawn up by the Common Assembly, the ECSC parliamentary chamber, the proposed defense community was rejected by the French Parliament. ECSC President Jean Monnet, a leading figure behind the communities, resigned from the High Authority in protest and began work on alternative communities, based on economic integration rather than political integration. After the Messina Conference in 1955, Paul Henri Spaak was given the task to prepare a report on the idea of a customs union. The so-called Spaak Report of the Spaak Committee formed the cornerstone of the intergovernmental negotiations at Val Duchesse conference centre in 1956. Together with the Ohlin Report the Spaak Report would provide the basis for the Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was sig ...

.

In 1956, Paul Henri Spaak led the Intergovernmental Conference on the Common Market and Euratom at the Val Duchesse conference centre, which prepared for the Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was sig ...

in 1957. The conference led to the signature, on 25 March 1957, of the Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was sig ...

establishing a European Economic Community.

Creation and early years

The resulting communities were the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM or sometimes EAEC). These were markedly less supranational than the previous communities, due to protests from some countries that theirsovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

was being infringed (however there would still be concerns with the behaviour of the Hallstein Commission). Germany became a founding member of the EEC, and Konrad Adenauer was made leader in a very short time. The first formal meeting of the Hallstein Commission was held on 16 January 1958 at the Chateau de Val-Duchesse. The EEC (direct ancestor of the modern Community) was to create a customs union while Euratom would promote co-operation in the nuclear power sphere. The EEC rapidly became the most important of these and expanded its activities. One of the first important accomplishments of the EEC was the establishment (1962) of common price levels for agricultural products. In 1968, internal tariffs (tariffs on trade between member nations) were removed on certain products.

Another crisis was triggered in regard to proposals for the financing of the Common Agricultural Policy, which came into force in 1962. The transitional period whereby decisions were made by unanimity had come to an end, and majority-voting in the council had taken effect. Then- French President Charles de Gaulle's opposition to supranationalism and fear of the other members challenging the CAP led to an "empty chair policy" whereby French representatives were withdrawn from the European institutions until the French veto was reinstated. Eventually, a compromise was reached with the Luxembourg compromise on 29 January 1966 whereby a gentlemen's agreement permitted members to use a veto on areas of national interest.

On 1 July 1967 when the Merger Treaty came into operation, combining the institutions of the ECSC and Euratom into that of the EEC, they already shared a Parliamentary Assembly and

Another crisis was triggered in regard to proposals for the financing of the Common Agricultural Policy, which came into force in 1962. The transitional period whereby decisions were made by unanimity had come to an end, and majority-voting in the council had taken effect. Then- French President Charles de Gaulle's opposition to supranationalism and fear of the other members challenging the CAP led to an "empty chair policy" whereby French representatives were withdrawn from the European institutions until the French veto was reinstated. Eventually, a compromise was reached with the Luxembourg compromise on 29 January 1966 whereby a gentlemen's agreement permitted members to use a veto on areas of national interest.

On 1 July 1967 when the Merger Treaty came into operation, combining the institutions of the ECSC and Euratom into that of the EEC, they already shared a Parliamentary Assembly and Courts

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accor ...

. Collectively they were known as the '' European Communities''. The Communities still had independent personalities although were increasingly integrated. Future treaties granted the community new powers beyond simple economic matters which had achieved a high level of integration. As it got closer to the goal of political integration and a peaceful and united Europe, what Mikhail Gorbachev described as a ''Common European Home

The "Common European Home" was a concept created and espoused by former Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev.

The concept has some antecedents in Leonid Brezhnev's foreign policy, who used the phrase during a visit to Bonn, West Germany, ...

''.

Enlargement and elections

The 1960s saw the first attempts at enlargement. In 1961,Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establishe ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

(in 1962), applied to join the three Communities. However, President Charles de Gaulle saw British membership as a Trojan horse for U.S. influence and vetoed membership, and the applications of all four countries were suspended. Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

became the first country to join the EC in 1961 as an associate member, however its membership was suspended in 1967 after a coup d'état established a military dictatorship called the Regime of the Colonels.

A year later, in February 1962, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

attempted to join the European Communities. However, because Francoist Spain

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Sp ...

was not a democracy, all members rejected the request in 1964.

The four countries resubmitted their applications on 11 May 1967 and with Georges Pompidou succeeding Charles de Gaulle as French president in 1969, the veto was lifted. Negotiations began in 1970 under the pro-European UK government of Edward Heath, who had to deal with disagreements relating to the Common Agricultural Policy and the UK's relationship with the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

. Nevertheless, two years later the accession treaties were signed so that Denmark, Ireland and the UK joined the Community effective 1 January 1973. The Norwegian people had finally rejected membership in a referendum on 25 September 1972.

The Treaties of Rome had stated that the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adop ...

must be directly elected, however this required the Council to agree on a common voting system first. The Council procrastinated on the issue and the Parliament remained appointed, French President Charles de Gaulle was particularly active in blocking the development of the Parliament, with it only being granted Budgetary powers following his resignation.

Parliament pressured for agreement and on 20 September 1976 the Council agreed part of the necessary instruments for election, deferring details on electoral systems which remain varied to this day. During the tenure of President Jenkins, in June 1979, the elections were held in all the then-members (see 1979 European Parliament election). The new Parliament, galvanised by direct election and new powers, started working full-time and became more active than the previous assemblies.

Shortly after its election, the Parliament proposed that the Community adopt the flag of Europe design used by the Council of Europe. The European Council in 1984 appointed an ''ad hoc'' committee for this purpose. The European Council in 1985 largely followed the Committee's recommendations, but as the adoption of a flag was strongly reminiscent of a national flag representing statehood

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state. One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a "sta ...

, was controversial, the "flag of Europe" design was adopted only with the status of a "logo" or "emblem".

The European Council, or European summit, had developed since the 1960s as an informal meeting of the Council at the level of heads of state. It had originated from then- French President Charles de Gaulle's resentment at the domination of supranational institutions (e.g. the Commission) over the integration process. It was mentioned in the treaties for the first time in the Single European Act (see below).

Toward Maastricht

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

re-applied to join the community on 12 June 1975, following the restoration of democracy, and joined on 1 January 1981. Following on from Greece, and after their own democratic restoration, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

applied to the communities in 1977 and joined together on 1 January 1986. In 1987 Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

formally applied to join the Community and began the longest application process for any country.

With the prospect of further enlargement, and a desire to increase areas of co-operation, the Single European Act was signed by the foreign ministers on 17 and 28 February 1986 in Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small land ...

and The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a list of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's ad ...

respectively. In a single document it dealt with reform of institutions, extension of powers, foreign policy cooperation and the single market. It came into force on 1 July 1987. The act was followed by work on what would be the Maastricht Treaty, which was agreed on 10 December 1991, signed the following year and coming into force on 1 November 1993 establishing the European Union, and paving the way for the European Monetary Union.

European Community

The EU absorbed the European Communities as one of its three pillars. The EEC's areas of activities were enlarged and were renamed the ''European Community'', continuing to follow the supranational structure of the EEC. The EEC institutions became those of the EU, however the Court, Parliament and Commission had only limited input in the new pillars, as they worked on a more intergovernmental system than the European Communities. This was reflected in the names of the institutions, the Council was formally the "Council of the ''European Union''" while the Commission was formally the "Commission of the ''European Communities''". However, after the Treaty of Maastricht, Parliament gained a much bigger role. Maastricht brought in the codecision procedure, which gave it equal legislative power with the Council on Community matters. Hence, with the greater powers of the supranational institutions and the operation of Qualified Majority Voting in the Council, the Community pillar could be described as a far more federal method of decision making. The Treaty of Amsterdam transferred responsibility for free movement of persons (e.g.,visas

Visa most commonly refers to:

* Visa Inc., a US multinational financial and payment cards company

** Visa Debit card issued by the above company

** Visa Electron, a debit card

** Visa Plus, an interbank network

*Travel visa, a document that allo ...

, illegal immigration, asylum) from the Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) pillar to the European Community (JHA was renamed Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC) as a result).What are the three pillars of the EU?Folketingets EU-Oplysning Both Amsterdam and the Treaty of Nice also extended codecision procedure to nearly all policy areas, giving Parliament equal power to the Council in the Community. In 2002, the Treaty of Paris which established the ECSC expired, having reached its 50-year limit (as the first treaty, it was the only one with a limit). No attempt was made to renew its mandate; instead, the Treaty of Nice transferred certain of its elements to the

Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was sig ...

and hence its work continued as part of the EC area of the European Community's remit.

After the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009 the pillar structure ceased to exist. The European Community, together with its legal personality, was absorbed into the newly consolidated European Union which merged in the other two pillars (however Euratom remained distinct). This was originally proposed under the European Constitution but that treaty failed ratification in 2005.

Aims and achievements

The main aim of the EEC, as stated in its preamble, was to "preserve peace and liberty and to lay the foundations of an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe". Calling for balanced economic growth, this was to be accomplished through: # The establishment of a customs union with a common external tariff # Common policies foragriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peop ...

, transport and trade, including standardization

Standardization or standardisation is the process of implementing and developing technical standards based on the consensus of different parties that include firms, users, interest groups, standards organizations and governments. Standardization ...

(for example, the CE marking designates standards compliance)

# Enlargement of the EEC to the rest of Europe

Citing Article 2 from the original text of the Treaty of Rome of the 25th of March 1957, the EEC aimed at “a harmonious development of economic activities, a continuous and balanced expansion, an increase in stability, an accelerated raising of the standard of living and closer relations between the States belonging to it”. Given the fear of the Cold War, many Western Europeans were afraid that poverty would make “the population vulnerable to communist propaganda” (Meurs 2018, p. 68), meaning that increasing prosperity would be beneficial to harmonise power between the Western and Eastern blocs, other than reconcile Member States such as France and Germany after WW2. The tasks entrusted to the Community were divided among an assembly, the European Parliament, Council, Commission, and Court of Justice. Moreover, restrictions to market were lifted to further liberate trade among Member States. Citizens of Member States (other than goods, services, and capital) were entitled to freedom of movement. The CAP, Common Agricultural Policy, regulated and subsided the agricultural sphere. A European Social Fund was implemented in favour of employees who lost their jobs. A European Investment Bank was established to “facilitate the economic expansion of the Community by opening up fresh resources” (Art. 3 Treaty of Rome 3/25/1957). All these implementations included overseas territories. Competition was to be kept alive to make products cheaper for European consumers.

For the customs union, the treaty provided for a 10% reduction in custom duties and up to 20% of global import quotas. Progress on the customs union proceeded much faster than the twelve years planned. However, France faced some setbacks due to their war with Algeria.

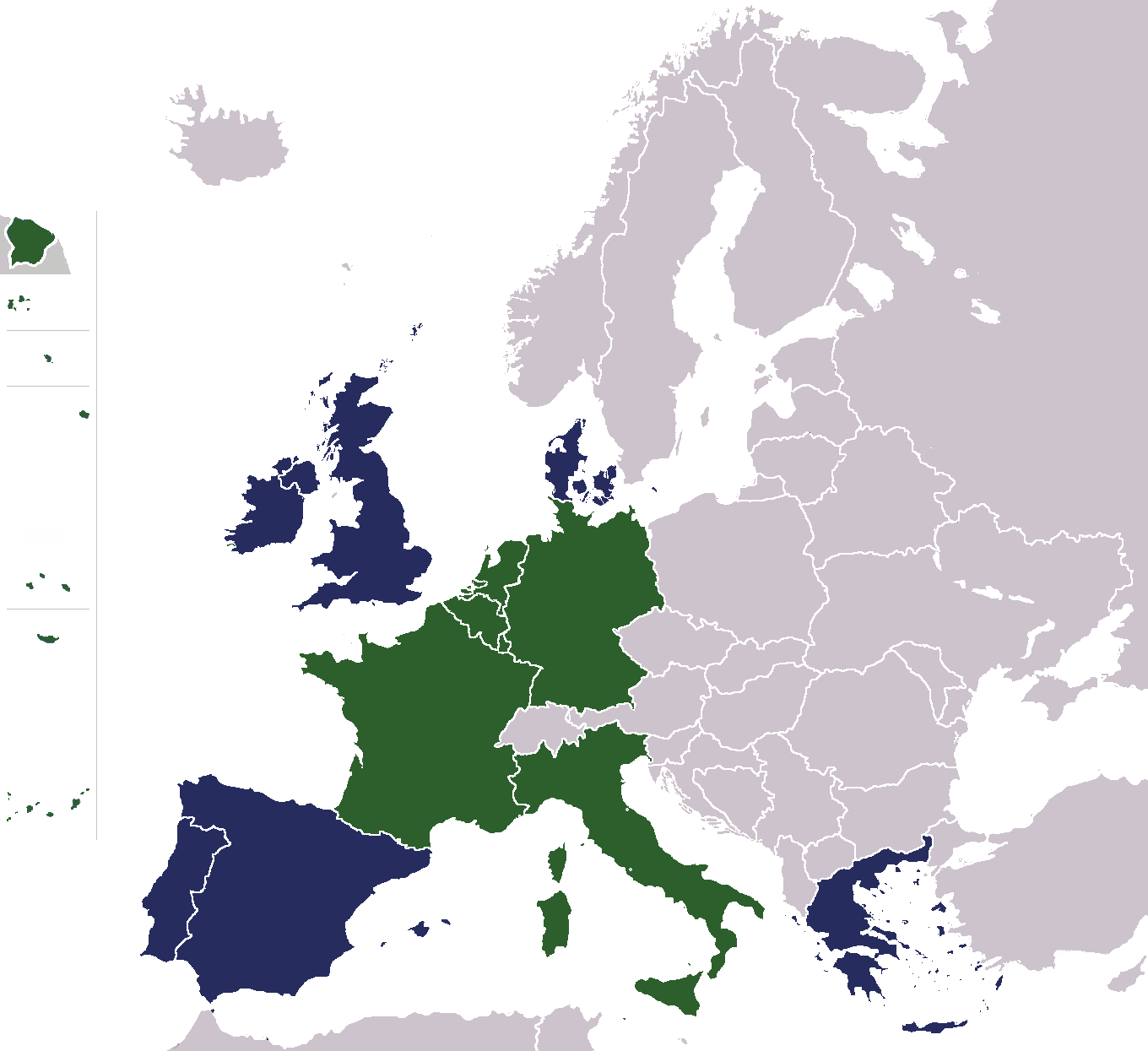

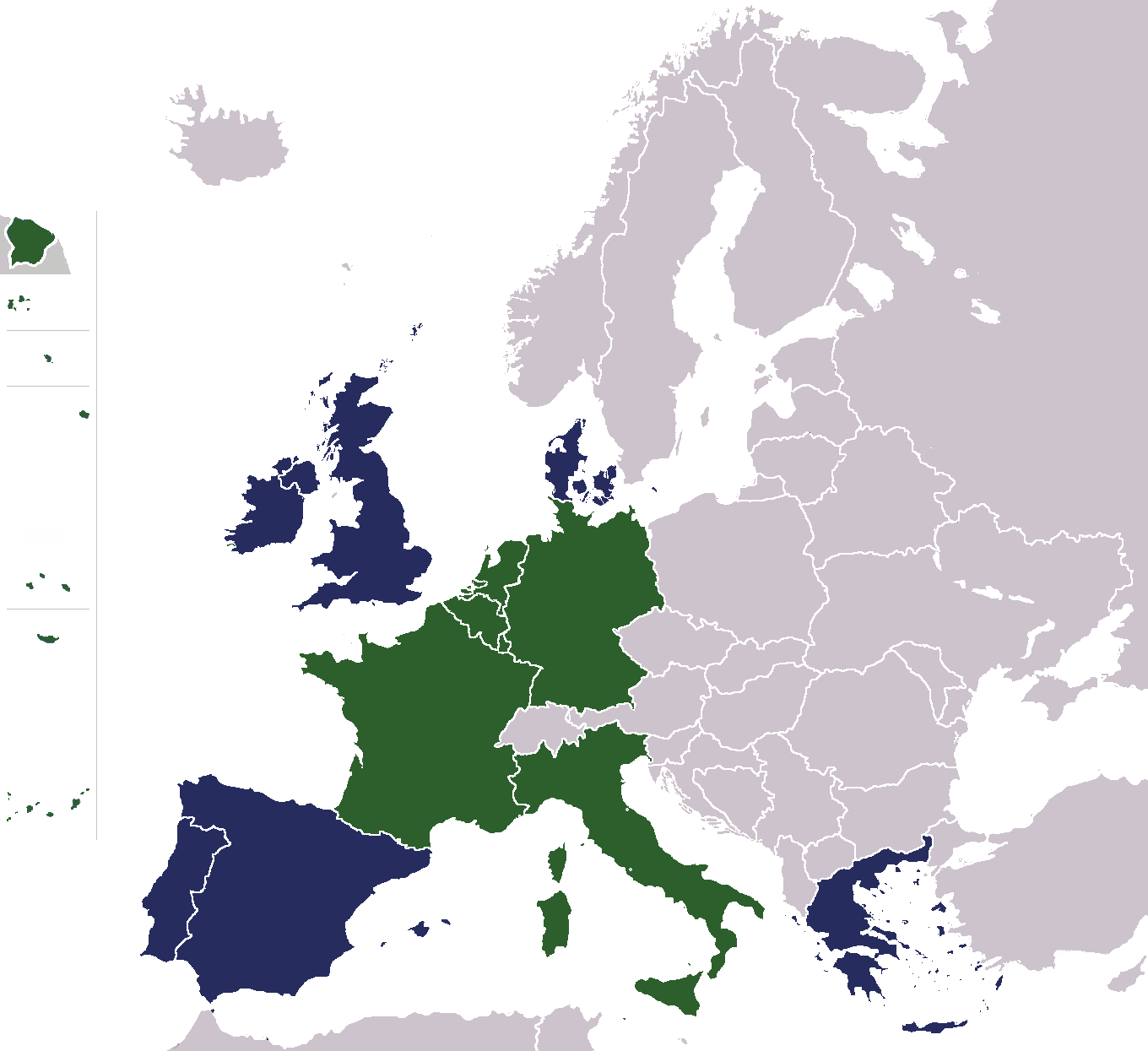

Members

The six states that founded the EEC and the other two Communities were known as the " inner six" (the "outer seven" were those countries who formed the European Free Trade Association). The six were France, West Germany, Italy and the three Benelux countries: Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. The first enlargement was in 1973, with the accession of Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom. Greece, Spain and Portugal joined in the 1980s. The formerEast Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

became part of the EEC upon German reunification in 1990. Following the creation of the EU in 1993, it has enlarged to include an additional sixteen countries by 2013.

Member states are represented in some form in each institution. The Council is also composed of one national minister who represents their national government. Each state also has a right to one European Commissioner each, although in the European Commission they are not supposed to represent their national interest but that of the Community. Prior to 2004, the larger members (France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom) have had two Commissioners. In the

Member states are represented in some form in each institution. The Council is also composed of one national minister who represents their national government. Each state also has a right to one European Commissioner each, although in the European Commission they are not supposed to represent their national interest but that of the Community. Prior to 2004, the larger members (France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom) have had two Commissioners. In the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adop ...

, members are allocated a set number seats related to their population, however these ( since 1979) have been directly elected and they sit according to political allegiance, not national origin. Most other institutions, including the European Court of Justice, have some form of national division of its members.

Institutions

There were three political institutions which held the executive and legislative power of the EEC, plus one judicial institution and a fifth body created in 1975. These institutions (except for the auditors) were created in 1957 by the EEC but from 1967 onwards they applied to all three Communities. The Council represents the state governments, the Parliament represents citizens and the Commission represents the European interest. Essentially, the Council, Parliament or another party place a request for legislation to the Commission. The Commission then drafts this and presents it to the Council for approval and the Parliament for an opinion (in some cases it had a veto, depending upon the legislative procedure in use). The Commission's duty is to ensure it is implemented by dealing with the day-to-day running of the Union and taking others to Court if they fail to comply. After the Maastricht Treaty in 1993, these institutions became those of the European Union, though limited in some areas due to the pillar structure. Despite this, Parliament in particular has gained more power over legislation and security of the Commission. The Court of Justice was the highest authority in the law, settling legal disputes in the Community, while the Auditors had no power but to investigate.Background

Council

The Council of the European Communities was a body holding legislative and executive powers and was thus the main decision making body of the Community. Its Presidency rotated between the member states every six months and it is related to the European Council, which was an informal gathering of national leaders (started in 1961) on the same basis as the Council.

The Council was composed of one national

The Council of the European Communities was a body holding legislative and executive powers and was thus the main decision making body of the Community. Its Presidency rotated between the member states every six months and it is related to the European Council, which was an informal gathering of national leaders (started in 1961) on the same basis as the Council.

The Council was composed of one national minister

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

from each member state. However the Council met in various forms depending upon the topic. For example, if agriculture was being discussed, the Council would be composed of each national minister for agriculture. They represented their governments and were accountable to their national political systems. Votes were taken either by majority (with votes allocated according to population) or unanimity. In these various forms they share some legislative and budgetary power of the Parliament. Since the 1960s the Council also began to meet informally at the level of heads of government and heads of state; these European summits followed the same presidency system and secretariat as the Council but was not a formal formation of it.

Commission

The Commission of the European Communities was the executive arm of the community, drafting Community law, dealing with the day to running of the Community and upholding the treaties. It was designed to be independent, representing the interest of the Community as a whole. Every member state submitted one commissioner (two from each of the larger states, one from the smaller states). One of its members was the President, appointed by the Council, who chaired the body and represented it.Parliament

Under the Community, the

Under the Community, the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adop ...

(formerly the European Parliamentary Assembly) had an advisory role to the Council and Commission. There were a number of Community legislative procedures, at first there was only the consultation procedure, which meant Parliament had to be consulted, although it was often ignored. The Single European Act gave Parliament more power, with the assent procedure giving it a right to veto proposals and the cooperation procedure giving it equal power with the Council if the Council was not unanimous.

In 1970 and 1975, the Budgetary treaties gave Parliament power over the Community budget. The Parliament's members, up-until 1980 were national MPs serving part-time in the Parliament. The Treaties of Rome had required elections to be held once the Council had decided on a voting system, but this did not happen and elections were delayed until 1979 (see 1979 European Parliament election). After that, Parliament was elected every five years. In the following 20 years, it gradually won co-decision powers with the Council over the adoption of legislation, the right to approve or reject the appointment of the Commission President and the Commission as a whole, and the right to approve or reject international agreements entered into by the Community.

Court

The Court of Justice of the European Communities was the highest court of on matters of Community law and was composed of one judge per state with a president elected from among them. Its role was to ensure that Community law was applied in the same way across all states and to settle legal disputes between institutions or states. It became a powerful institution as Community law overrides national law.Auditors

The fifth institution is the '' European Court of Auditors''. Its ensured that taxpayer funds from the Community budget had been correctly spent by the Community's institutions. The ECA provided an audit report for each financial year to the Council and Parliament and gave opinions and proposals on financial legislation and anti-fraud actions. It is the only institution not mentioned in the original treaties, having been set up in 1975.Policy areas

At the time of its abolition, the European Community pillar covered the following areas;See also

* Economy of the European Union * Brussels and the European Union * Delors Commission * European Commission * European Customs Information Portal (ECIP) * European Institutions in Strasbourg * History of the European Communities (1958-1972) *History of the European Communities (1973-1993)

The European Union is a geo-political entity covering a large portion of the European continent. It is founded upon numerous treaties and has undergone expansions and secessions that have taken it from six member states to 27, a majority of the ...

* Location of European Union institutions

* Snake in the tunnel

EU evolution timeline

Notes

References

Further reading

* Acocella, Nicola (1992), ‘''Trade and direct investment within the EC: The impact of strategic considerations''’, in: Cantwell, John (ed.), ‘''Multinational investment in modern Europe''’, E. Elgar, Cheltenham, . * Balassa, Bela (1962). ''The Theory of Economic Integration'' * * Hallstein, Walter (1962). ''A New Path to Peaceful Union'' * Milward, Alan S. (1992). ''The European Rescue of the Nation-State'' * Moravcsik, Andrew (1998). ''The Choice for Europe. Social Purpose and State Power from Messina to Maastricht'Books

* Ludlow, N. Piers (2006). ''The European Community and the Crises of the 1960s. Negotiating the Gaullist Challenge'

The European Community and the Crises of the 1960s: Negotiating the Gaullist Challenge

* Warlouzet, Laurent (2018). ''Governing Europe in a Globalizing World. Neoliberalism and its Alternatives following the 1973 Oil Crisis'

Governing Europe in a Globalizing World: Neoliberalism and its Alternatives following the 1973 Oil Crisis

Primary sources

* Bliss, Howard, ed. ''The political development of the European Community: a documentary collection'' (Blaisdell, 1969). * Monnet, Jean. ''Prospect for a New Europe'' (1959). * Schuman, Robert. ''French Policy towards Germany since the war'' (Oxford University Press, 1954). * Spaak, Paul-Henri. ''The Continuing Battle: Memories of a European'' (1971)External links

EEC on the UK Parliament website

Documents

of the European Economic Community are consultable at th

Historical Archives of the EU

in Florence

on CVCE website

History of the Rome Treaties

on CVCE website

* ttp://ec.europa.eu/ecip/index_en.htm European Customs Information Portal (ECIP)br>The history of the European Union

{{Authority control History of the European Union Organizations established in 1958 Organizations disestablished in 1993 Former international organizations 1958 establishments in Europe 1993 disestablishments in Europe States and territories established in 1958