Eugenics Society Poster (1930s) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

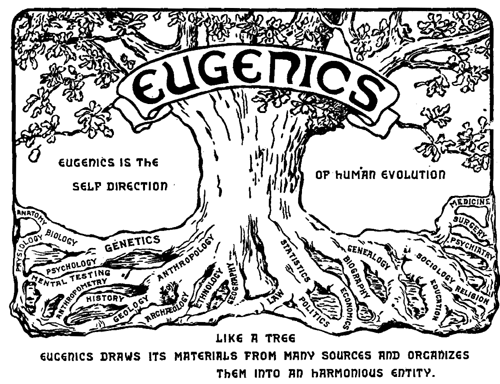

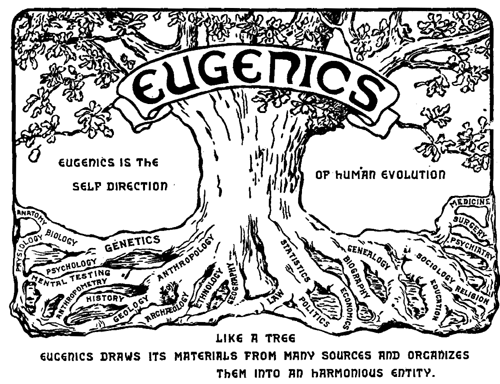

Eugenics ( ; ) is a

The idea of a modern project for improving the human population through selective breeding was originally developed by

The idea of a modern project for improving the human population through selective breeding was originally developed by  Three

Three  In addition to being practiced in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the

In addition to being practiced in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the

Eugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics

, Chesterton's 1917 book '' Eugenics and Other Evils'', and Boas' 1916 article "

The scientific reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when

The scientific reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when

fringe

Fringe may refer to:

Arts

* Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the world's largest arts festival, known as "the Fringe"

* Adelaide Fringe, the world's second-largest annual arts festival

* Fringe theatre, a name for alternative theatre

* The Fringe, the ...

set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or promoting those judged to be superior. In recent years, the term has seen a revival in bioethical discussions on the usage of new technologies such as CRISPR

CRISPR () (an acronym for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea. These sequences are derived from DNA fragments of bacte ...

and genetic screening

Genetic testing, also known as DNA testing, is used to identify changes in DNA sequence or chromosome structure. Genetic testing can also include measuring the results of genetic changes, such as RNA analysis as an output of gene expression, or ...

, with a heated debate on whether these technologies should be called eugenics or not.

The concept predates the term; Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

suggested applying the principles of selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant mal ...

to humans around 400 BC. Early advocates of eugenics in the 19th century regarded it as a way of improving groups of people. In contemporary usage, the term ''eugenics'' is closely associated with scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

. Modern bioethicists

Bioethics is both a field of study and professional practice, interested in ethical issues related to health (primarily focused on the human, but also increasingly includes animal ethics), including those emerging from advances in biology, med ...

who advocate new eugenics

New eugenics, also known as liberal eugenics (a term coined by bioethicist Nicholas Agar), advocates enhancing human characteristics and capacities through the use of reproductive technology and human genetic engineering. Those who advocate new eu ...

characterize it as a way of enhancing individual traits, regardless of group membership.

While eugenic principles have been practiced as early as ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, the contemporary history of eugenics

The history of eugenics is the study of development and advocacy of ideas related to eugenics around the world. Early eugenic ideas were discussed in Ancient Greece and Rome. The height of the modern eugenics movement came in the late 19th and earl ...

began in the late 19th century, when a popular eugenics movement emerged in the United Kingdom, and then spread to many countries, including the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, Canada, Australia, and most European countries. In this period, people from across the political spectrum espoused eugenic ideas. Consequently, many countries adopted eugenic policies, intended to improve the quality of their populations' genetic stock. Such programs included both ''positive'' measures, such as encouraging individuals deemed particularly "fit" to reproduce, and ''negative'' measures, such as marriage prohibitions and forced sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to Involuntary treatment, involuntarily Sterilization (medicine), sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's ca ...

of people deemed unfit for reproduction. Those deemed "unfit to reproduce" often included people with mental or physical disabilities

A physical disability is a limitation on a person's physical functioning, mobility, dexterity or stamina. Other physical disability, disabilities include impairments which limit other facets of daily living skills, daily living, such as respiratory ...

, people who scored in the low ranges on different IQ tests

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence. The abbreviation "IQ" was coined by the psychologist William Stern for the German term ''Intelligenzqu ...

, criminals and "deviants", and members of disfavored minority groups

The term 'minority group' has different usages depending on the context. According to its common usage, a minority group can simply be understood in terms of demographic sizes within a population: i.e. a group in society with the least number o ...

.

The eugenics movement became associated with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

when the defense of many of the defendants at the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

of 1945 to 1946 attempted to justify their human-rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hum ...

abuses by claiming there was little difference between the Nazi eugenics

Nazi eugenics refers to the social policies of eugenics in Nazi Germany, composed of various pseudoscientific ideas about genetics. The racial ideology of Nazism placed the biological improvement of the German people by selective breeding of ...

programs and the U.S. eugenics programs. In the decades following World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, with more emphasis on human rights, many countries began to abandon eugenics policies, although some Western countries (the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, and Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

among them) continued to carry out forced sterilizations.

Since the 1980s and 1990s, with new assisted reproductive technology

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) includes medical procedures used primarily to address infertility. This subject involves procedures such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), cryopreservation of gametes o ...

procedures available, such as gestational surrogacy

Surrogacy is an arrangement, often supported by a legal agreement, whereby a woman agrees to delivery/labour for another person or people, who will become the child's parent(s) after birth. People may seek a surrogacy arrangement when pregnan ...

(available since 1985), preimplantation genetic diagnosis

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD or PIGD) is the genetic profiling of embryos prior to implantation (as a form of embryo profiling), and sometimes even of oocytes prior to fertilization. PGD is considered in a similar fashion to prenatal ...

(available since 1989), and cytoplasmic transfer

Mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT), sometimes called mitochondrial donation, is the replacement of mitochondria in one or more cells to prevent or ameliorate disease. MRT originated as a special form of in vitro fertilisation in which some or ...

(first performed in 1996), concern has grown about the possible revival of a more potent form of eugenics after decades of promoting human rights.

A criticism of eugenics policies is that, regardless of whether ''negative'' or ''positive'' policies are used, they are susceptible to abuse because the genetic selection criteria are determined by whichever group has political power at the time. Furthermore, many criticize ''negative eugenics'' in particular as a violation of basic human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

, seen since 1968's Proclamation of Tehran as including the right to reproduce. Another criticism is that eugenics policies eventually lead to a loss of genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

, thereby resulting in inbreeding depression

Inbreeding depression is the reduced biological fitness which has the potential to result from inbreeding (the breeding of related individuals). Biological fitness refers to an organism's ability to survive and perpetuate its genetic material. In ...

due to a loss of genetic variation. Yet another criticism of contemporary eugenics policies is that they propose to permanently and artificially disrupt millions of years of human evolution, and that attempting to create genetic lines "clean" of "disorders" can have far-reaching ancillary downstream effects in the genetic ecology, including negative effects on immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

and on species resilience.

History

Origin and development

Types of eugenic practices have existed for millennia. Someindigenous peoples of Brazil

Indigenous peoples in Brazil ( pt, povos indígenas no Brasil) or Indigenous Brazilians ( pt, indígenas brasileiros, links=no) once comprised an estimated 2000 tribes and nations inhabiting what is now the country of Brazil, before European con ...

are known to have practiced infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose is the prevention of reso ...

against children born with physical abnormalities since precolonial times. In ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, the philosopher Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

suggested selective mating to produce a guardian class. In Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

, every Spartan child was inspected by the council of elders, the Gerousia

The Gerousia (γερουσία) was the council of elders in ancient Sparta. Sometimes called Spartan senate in the literature, it was made up of the two Spartan kings, plus 28 men over the age of sixty, known as gerontes. The Gerousia was a pr ...

, which determined if the child was fit to live or not.

The geographer Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

states that the Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they for ...

would take ten virgin

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

women and ten young men who were considered to be the best representation of their sex

Sex is the trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing animal or plant produces male or female gametes. Male plants and animals produce smaller mobile gametes (spermatozoa, sperm, pollen), while females produce larger ones ( ova, of ...

and mate

Mate may refer to:

Science

* Mate, one of a pair of animals involved in:

** Mate choice, intersexual selection

** Mating

* Multi-antimicrobial extrusion protein, or MATE, an efflux transporter family of proteins

Person or title

* Friendship ...

them. Following this, the best women would be given to the best male, then the second-best women to the second-best male. It is possible that the "best" men and women were chosen based on athletic capabilities. This would continue until all 20 people had been assigned to one another. If the people involved dishonor themselves, they would have been removed and forcefully separated from their partner.

In the early years of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

, a Roman father was obliged by law to immediately kill his child if they were "dreadfully deformed". According to Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

, a Roman of the Imperial Period, the Germanic tribes of his day killed any member of their community they deemed cowardly, unwarlike or "stained with abominable vices", usually by drowning them in swamps. Modern historians, however, see Tacitus' ethnographic writing as unreliable in such details.

The idea of a modern project for improving the human population through selective breeding was originally developed by

The idea of a modern project for improving the human population through selective breeding was originally developed by Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto- ...

, and was initially inspired by Darwinism

Darwinism is a scientific theory, theory of Biology, biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of smal ...

and its theory of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

. Galton had read his half-cousin Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

, which sought to explain the development of plant and animal species, and desired to apply it to humans. Based on his biographical studies, Galton believed that desirable human qualities were hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

traits, although Darwin strongly disagreed with this elaboration of his theory. In 1883, one year after Darwin's death, Galton gave his research a name: ''eugenics''. With the introduction of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

, eugenics became associated with genetic determinism

Biological determinism, also known as genetic determinism, is the belief that human behaviour is directly controlled by an individual's genes or some component of their physiology, generally at the expense of the role of the environment, whether ...

, the belief that human character is entirely or in the majority caused by genes, unaffected by education or living conditions. Many of the early geneticists were not Darwinians, and evolution theory was not needed for eugenics policies based on genetic determinism. Throughout its recent history, eugenics has remained controversial.

Eugenics became an academic discipline at many colleges and universities and received funding from many sources. Organizations were formed to win public support and sway opinion towards responsible eugenic values in parenthood, including the British Eugenics Education Society

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

of 1907 and the American Eugenics Society

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans

Americans are the Citizenship of the United States, citizens and United S ...

of 1921. Both sought support from leading clergymen and modified their message to meet religious ideals. In 1909, the Anglican clergymen William Inge

William Motter Inge (; May 3, 1913 – June 10, 1973) was an American playwright and novelist, whose works typically feature solitary protagonists encumbered with strained sexual relations. In the early 1950s he had a string of memorable Broad ...

and James Peile both wrote for the Eugenics Education Society. Inge was an invited speaker at the 1921 International Eugenics Conference

Three International Eugenics Congresses took place between 1912 and 1932 and were the global venue for scientists, politicians, and social leaders to plan and discuss the application of programs to improve human heredity in the early twentieth cen ...

, which was also endorsed by the Roman Catholic Archbishop of New York Patrick Joseph Hayes

Patrick Joseph Hayes (November 20, 1867 – September 4, 1938) was an American cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as Archbishop of New York from 1919 until his death, and was elevated to the cardinalate in 1924.

Early life and ...

. The book ''The Passing of the Great Race

''The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History'' is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific book by American lawyer, self-styled anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics, Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theor ...

'' (''Or, The Racial Basis of European History'') by American eugenicist, lawyer, and amateur anthropologist Madison Grant

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known primarily for his work as a eugenicist and conservationist, and as an advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted f ...

was published in 1916. Although influential, the book was largely ignored when it first appeared, and it went through several revisions and editions. Nevertheless, the book was used by people who advocated restricted immigration as justification for what became known as "scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

".

Three

Three International Eugenics Conference

Three International Eugenics Congresses took place between 1912 and 1932 and were the global venue for scientists, politicians, and social leaders to plan and discuss the application of programs to improve human heredity in the early twentieth cen ...

s presented a global venue for eugenists with meetings in 1912 in London, and in 1921 and 1932 in New York City. Eugenic policies in the United States were first implemented in the early 1900s. It also took root in France, Germany, and Great Britain. Later, in the 1920s and 1930s, the eugenic policy of sterilizing certain mental patients was implemented in other countries including Belgium, Brazil, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

and Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

. Frederick Osborn

Major General Frederick Henry Osborn CBE (21 March 1889 – 5 January 1981) was an American philanthropist, military leader, and eugenicist. He was a founder of several organizations and played a central part in reorienting eugenics in the y ...

's 1937 journal article "Development of a Eugenic Philosophy" framed it as a social philosophy

Social philosophy examines questions about the foundations of social institutions, social behavior, and interpretations of society in terms of ethical values rather than empirical relations. Social philosophers emphasize understanding the social ...

—a philosophy with implications for social order

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social order ...

. That definition is not universally accepted. Osborn advocated for higher rates of sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

among people with desired traits ("positive eugenics") or reduced rates of sexual reproduction or sterilization of people with less-desired or undesired traits ("negative eugenics").

In addition to being practiced in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the

In addition to being practiced in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations The International Federation of Eugenic Organizations (IFEO) was an international organization of groups and individuals focused on eugenics. Founded in London in 1912, where it was originally titled the Permanent International Eugenics Committee, i ...

. Its scientific aspects were carried on through research bodies such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics

The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics was founded in 1927 in Berlin, Germany. The Rockefeller Foundation partially funded the actual building of the Institute and helped keep the Institute afloat during the Gr ...

, the Cold Spring Harbor Carnegie Institution for Experimental Evolution

Experimental evolution is the use of laboratory experiments or controlled field manipulations to explore evolutionary dynamics. Evolution may be observed in the laboratory as individuals/populations adapt to new environmental conditions by natura ...

, and the Eugenics Record Office

The Eugenics Record Office (ERO), located in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, United States, was a research institute that gathered biological and social information about the American population, serving as a center for eugenics and human heredity ...

. Politically, the movement advocated measures such as sterilization laws. In its moral dimension, eugenics rejected the doctrine that all human beings are born equal and redefined moral worth purely in terms of genetic fitness. Its racist elements included pursuit of a pure "Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming th ...

" or "Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

" genetic pool and the eventual elimination of "unfit" races. Many leading British politicians subscribed to the theories of eugenics. Winston Churchill supported the British Eugenics Society and was an honorary vice president for the organization. Churchill believed that eugenics could solve "race deterioration" and reduce crime and poverty.

Early critics of the philosophy of eugenics included the American sociologist Lester Frank Ward

Lester Frank Ward (June 18, 1841 – April 18, 1913) was an American botanist, paleontologist, and sociologist. He served as the first president of the American Sociological Association.

In service of democratic development, polymath Lester W ...

, the English writer G. K. Chesterton, the German-American anthropologist Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

, who argued that advocates of eugenics greatly over-estimate the influence of biology, and Scottish tuberculosis pioneer and author Halliday Sutherland

Halliday Gibson Sutherland (1882–1960) was a Scottish medical doctor, writer, opponent of eugenics and the producer of Britain's first public health education cinema film in 1911.

Private life

Halliday Sutherland was born in Glasgow, Scotland ...

. Ward's 1913 articleEugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics

, Chesterton's 1917 book '' Eugenics and Other Evils'', and Boas' 1916 article "

Eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

" (published in ''The Scientific Monthly

''The Scientific Monthly'' was a science magazine published from 1915 to 1957. Psychologist James McKeen Cattell, the former publisher and editor of ''The Popular Science Monthly'', was the original founder and editor. In 1958, ''The Scientific Mo ...

'') were all harshly critical of the rapidly growing movement. Sutherland identified eugenists as a major obstacle to the eradication and cure of tuberculosis in his 1917 address "Consumption: Its Cause and Cure", and criticism of eugenists and Neo-Malthusians

Malthusianism is the idea that population growth is potentially exponential while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population die off. This event, c ...

in his 1921 book ''Birth Control'' led to a writ for libel from the eugenist Marie Stopes

Marie Charlotte Carmichael Stopes (15 October 1880 – 2 October 1958) was a British author, palaeobotanist and campaigner for eugenics and women's rights. She made significant contributions to plant palaeontology and coal classification, ...

. Several biologists were also antagonistic to the eugenics movement, including Lancelot Hogben

Lancelot Thomas Hogben FRS FRSE (9 December 1895 – 22 August 1975) was a British experimental zoologist and medical statistician. He developed the African clawed frog ''(Xenopus laevis)'' as a model organism for biological research in his ear ...

. Other biologists such as J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (; 5 November 18921 December 1964), nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biolog ...

and R. A. Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who ...

expressed skepticism in the belief that sterilization of "defectives" would lead to the disappearance of undesirable genetic traits.

Among institutions, the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

was an opponent of state-enforced sterilizations, but accepted isolating people with hereditary diseases so as not to let them reproduce. Attempts by the Eugenics Education Society to persuade the British government to legalize voluntary sterilization were opposed by Catholics and by the Labour Party. The American Eugenics Society

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans

Americans are the Citizenship of the United States, citizens and United S ...

initially gained some Catholic supporters, but Catholic support declined following the 1930 papal encyclical ''Casti connubii

''Casti connubii'' (Latin: "of chaste wedlock") is a papal encyclical promulgated by Pope Pius XI on 31 December 1930 in response to the Lambeth Conference of the Anglican Communion. It stressed the sanctity of marriage, prohibited Catholics f ...

''. In this, Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fro ...

explicitly condemned sterilization laws: "Public magistrates have no direct power over the bodies of their subjects; therefore, where no crime has taken place and there is no cause present for grave punishment, they can never directly harm, or tamper with the integrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason."

As a social movement, eugenics reached its greatest popularity in the early decades of the 20th century, when it was practiced around the world and promoted by governments, institutions, and influential individuals (such as the playwright G. B. Shaw). Many countries enacted various eugenics policies, including: genetic screenings, birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

, promoting differential birth rates, marriage restrictions, segregation (both racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

and sequestering the mentally ill), compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done throug ...

, forced abortion

A forced abortion may occur when the perpetrator causes abortion by force, threat or coercion, or by taking advantage of a situation where a pregnant individual is unable to give consent, or when valid consent is in question due to duress. This ma ...

s or forced pregnancies

Forced pregnancy is the practice of forcing a woman to become pregnant against her will, often as part of a forced marriage, or as part of a programme of breeding slaves, or as part of a programme of genocide. Forced pregnancy is a form of reprod ...

, ultimately culminating in genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

. By 2014, gene selection (rather than "people selection") was made possible through advances in genome editing

Genome editing, or genome engineering, or gene editing, is a type of genetic engineering in which DNA is inserted, deleted, modified or replaced in the genome of a living organism. Unlike early genetic engineering techniques that randomly inserts ...

, leading to what is sometimes called ''new eugenics

New eugenics, also known as liberal eugenics (a term coined by bioethicist Nicholas Agar), advocates enhancing human characteristics and capacities through the use of reproductive technology and human genetic engineering. Those who advocate new eu ...

'', also known as "neo-eugenics", "consumer eugenics", or "liberal eugenics"; which focuses on individual freedom and allegedly pull away from racism, sexism, heterosexism or a focus on intelligence.

Eugenics in the United States

Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States

In the United States, anti-miscegenation laws (also known as miscegenation laws) were laws passed by most states that prohibited interracial marriage, and in some cases also prohibited interracial sexual relations. Some such laws predate the e ...

made it a crime for individuals to wed someone categorized as belonging to a different race. These laws were part of a broader policy of racial segregation in the United States

In the United States, racial segregation is the systematic separation of facilities and services such as Housing in the United States, housing, Healthcare in the United States, healthcare, Education in the United States, education, Employment in ...

to minimize contact between people of different ethnicities. Race laws and practices in the United States were explicitly used as models by the Nazi regime when it developed the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of th ...

, stripping Jewish citizens of their citizenship.

Nazism and the decline of eugenics

The scientific reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when

The scientific reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin

Ernst Rüdin (19 April 1874 – 22 October 1952) was a Swiss-born German psychiatrist, geneticist, eugenicist and Nazi, rising to prominence under Emil Kraepelin and assuming the directorship at the German Institute for Psychiatric Rese ...

used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

had praised and incorporated eugenic ideas in ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'' in 1925 and emulated eugenic legislation for the sterilization of "defectives" that had been pioneered in the United States once he took power. Some common early 20th century eugenics methods involved identifying and classifying individuals and their families, including the poor, mentally ill, blind, deaf, developmentally disabled, promiscuous women

Promiscuity tends to be frowned upon by many societies that expect most members to have committed, long-term relationships.

Among women, as well as men, inclination for sex outside committed relationships is correlated with a high libido, but ev ...

, homosexuals, and racial groups (such as the Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

*Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

and Jews in Nazi Germany

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (''circa'' 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jews, As ...

) as "degenerate" or "unfit", and therefore led to segregation, institutionalization, sterilization, and even mass murder

Mass murder is the act of murdering a number of people, typically simultaneously or over a relatively short period of time and in close geographic proximity. The United States Congress defines mass killings as the killings of three or more pe ...

. The Nazi policy of identifying German citizens deemed mentally or physically unfit and then systematically killing them with poison gas, referred to as the Aktion T4

(German, ) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of 4, a street address of ...

campaign, is understood by historians to have paved the way for the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

.

By the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, many eugenics laws were abandoned, having become associated with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

stated in his 1940 book ''The Rights of Man: Or What Are We Fighting For?'' that among the human rights, which he believed should be available to all people, was "a prohibition on

Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with factors of perceived

Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with factors of perceived

Eugenics: Its Origin and Development (1883 - Present)

by the

Eugenics and Scientific Racism Fact Sheet

by the

mutilation

Mutilation or maiming (from the Latin: ''mutilus'') refers to severe damage to the body that has a ruinous effect on an individual's quality of life. It can also refer to alterations that render something inferior, ugly, dysfunctional, or imper ...

, sterilization, torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts c ...

, and any bodily punishment". After World War II, the practice of "imposing measures intended to prevent births within national, ethnical, racial or religiousgroup" fell within the definition of the new international crime of genocide, set out in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to pursue the enforcement of its prohibition. It was ...

. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR) enshrines certain political, social, and economic rights for European Union (EU) citizens and residents into EU law. It was drafted by the European Convention and solemnly proclaim ...

also proclaims "the prohibition of eugenic practices, in particular those aiming at selection of persons". In spite of the decline in discriminatory eugenics laws, some government mandated sterilizations continued into the 21st century. During the ten years President Alberto Fujimori

Alberto Kenya Fujimori Inomoto ( or ; born 28 July 1938) is a Peruvian politician, professor and former engineer who was President of Peru from 28 July 1990 until 22 November 2000. Frequently described as a dictator,

*

*

*

*

*

*

he remains a ...

led Peru from 1990 to 2000, 2,000 persons were allegedly involuntarily sterilized. China maintained its one-child policy

The term one-child policy () refers to a population planning initiative in China implemented between 1980 and 2015 to curb the country's population growth by restricting many families to a single child. That initiative was part of a much bro ...

until 2015 as well as a suite of other eugenics based legislation to reduce population size and manage fertility rates of different populations. In 2007, the United Nations reported coercive sterilizations and hysterectomies in Uzbekistan. During the years 2005 to 2013, nearly one-third of the 144 California prison inmates who were sterilized did not give lawful consent to the operation.

Modern eugenics

Developments in genetic,genomic

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, three-dim ...

, and reproductive technologies

Reproductive technology encompasses all current and anticipated uses of technology in human and animal reproduction, including assisted reproductive technology, contraception and others. It is also termed Assisted Reproductive Technology, where it ...

at the beginning of the 21st century have raised numerous questions regarding the ethical status of eugenics, effectively creating a resurgence of interest in the subject. Some, such as UC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of Californi ...

sociologist Troy Duster

Troy Smith Duster (born July 11, 1936) is an American sociologist with research interests in the sociology of science, public policy, race and ethnicity and deviance. He is a Chancellor’s Professor of Sociology at University of California, Berke ...

, have argued that modern genetics is a back door to eugenics. This view was shared by then-White House Assistant Director for Forensic Sciences, Tania Simoncelli, who stated in a 2003 publication by the Population and Development Program at Hampshire College

Hampshire College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. It was opened in 1970 as an experiment in alternative education, in association with four other colleges ...

that advances in pre-implantation genetic diagnosis

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD or PIGD) is the genetic profiling of embryos prior to implantation (as a form of embryo profiling), and sometimes even of oocytes prior to fertilization. PGD is considered in a similar fashion to prena ...

(PGD) are moving society to a "new era of eugenics", and that, unlike the Nazi eugenics, modern eugenics is consumer driven and market based, "where children are increasingly regarded as made-to-order consumer products". In a 2006 newspaper article, Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biologist and author. He is an emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford and was Professor for Public Understanding of Science in the University of Oxford from 1995 to 2008. An ath ...

said that discussion regarding eugenics was inhibited by the shadow of Nazi misuse, to the extent that some scientists would not admit that breeding humans for certain abilities is at all possible. He believes that it is not physically different from breeding domestic animals for traits such as speed or herding skill. Dawkins felt that enough time had elapsed to at least ask just what the ethical differences were between breeding for ability versus training athletes or forcing children to take music lessons, though he could think of persuasive reasons to draw the distinction.

Lee Kuan Yew

Lee Kuan Yew (16 September 1923 – 23 March 2015), born Harry Lee Kuan Yew, often referred to by his initials LKY, was a Singaporean lawyer and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Singapore between 1959 and 1990, and Secretary-General o ...

, the founding father

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

of Singapore, promoted eugenics as late as 1983. A proponent of nature over nurture, he stated that "intelligence is 80% nature and 20% nurture", and attributed the successes of his children to genetics. In his speeches, Lee urged highly educated women to have more children, claiming that "social delinquents" would dominate unless their fertility rate increased. In 1984, Singapore began providing financial incentives to highly educated women to encourage them to have more children. In 1985, incentives were significantly reduced after public uproar.

In October 2015, the United Nations' International Bioethics Committee The International Bioethics Committee (IBC) of UNESCO is a body composed of 36 independent experts from all regions and different disciplines (mainly medicine, genetics, law, and philosophy) that follows progress in the life sciences and its applica ...

wrote that the ethical problems of human genetic engineering

Human genetic enhancement or human genetic engineering refers to human enhancement by means of a genetic modification. This could be done in order to cure diseases (gene therapy), prevent the possibility of getting a particular disease (similarly ...

should not be confused with the ethical problems of the 20th century eugenics movements. However, it is still problematic because it challenges the idea of human equality and opens up new forms of discrimination and stigmatization for those who do not want, or cannot afford, the technology.

The National Human Genome Research Institute

The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) is an institute of the National Institutes of Health, located in Bethesda, Maryland.

NHGRI began as the Office of Human Genome Research in The Office of the Director in 1988. This Office transi ...

says that eugenics is "inaccurate", "scientifically erroneous and immoral".

Transhumanism

Transhumanism is a philosophical and intellectual movement which advocates the enhancement of the human condition by developing and making widely available sophisticated technologies that can greatly enhance longevity and cognition.

Transhuma ...

is often associated with eugenics, although most transhumanists holding similar views nonetheless distance themselves from the term "eugenics" (preferring " germinal choice" or "reprogenetics

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) includes medical procedures used primarily to address infertility. This subject involves procedures such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), cryopreservation of gametes ...

") to avoid having their position confused with the discredited theories and practices of early-20th-century eugenic movements.

Prenatal screening

Prenatal testing consists of prenatal screening and prenatal diagnosis, which are aspects of prenatal care that focus on detecting problems with the pregnancy as early as possible. These may be anatomic and physiologic problems with the health of ...

has been called by some a contemporary form of eugenics because it may lead to abortions of fetuses with undesirable traits.

A system was proposed by California State Senator Nancy Skinner to compensate victims of the well-documented examples of prison sterilizations resulting from California's eugenics programs, but this did not pass by the bill's 2018 deadline in the Legislature.

Meanings and types

The term ''eugenics'' and its modern field of study were first formulated by Francis Galton in 1883, drawing on the recent work of his half-cousinCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

. Galton published his observations and conclusions in his book '' Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development''.

The origins of the concept began with certain interpretations of Mendelian inheritance

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularize ...

and the theories of August Weismann

August Friedrich Leopold Weismann FRS (For), HonFRSE, LLD (17 January 18345 November 1914) was a German evolutionary biologist. Fellow German Ernst Mayr ranked him as the second most notable evolutionary theorist of the 19th century, after Cha ...

. The word ''eugenics'' is derived from the Greek word ''eu'' ("good" or "well") and the suffix ''-genēs'' ("born"); Galton intended it to replace the word " stirpiculture", which he had used previously but which had come to be mocked due to its perceived sexual overtones. Galton defined eugenics as "the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations".

Historically, the idea of ''eugenics'' has been used to argue for a broad array of practices ranging from prenatal care

Prenatal care, also known as antenatal care, is a type of preventive healthcare. It is provided in the form of medical checkups, consisting of recommendations on managing a healthy lifestyle and the provision of medical information such as materna ...

for mothers deemed genetically desirable to the forced sterilization and murder of those deemed unfit. To population geneticists

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and between populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as adaptation, speciation, and pop ...

, the term has included the avoidance of inbreeding

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely related genetically. By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genetic disorders and o ...

without altering allele frequencies

Allele frequency, or gene frequency, is the relative frequency of an allele (variant of a gene) at a particular locus in a population, expressed as a fraction or percentage. Specifically, it is the fraction of all chromosomes in the population that ...

; for example, J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (; 5 November 18921 December 1964), nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biolog ...

wrote that "the motor bus, by breaking up inbred village communities, was a powerful eugenic agent." Debate as to what exactly counts as eugenics continues today.

Edwin Black

Edwin Black (born February 27, 1950) is an American historian and author, as well as a syndicated columnist, investigative journalist, and weekly talk show host on The Edwin Black Show. He specializes in human rights, the historical interplay be ...

, journalist and author of ''War Against the Weak'', argues that eugenics is often deemed a pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or falsifiability, unfa ...

because what is defined as a genetic improvement of a desired trait is a cultural choice rather than a matter that can be determined through objective scientific inquiry. The most disputed aspect of eugenics has been the definition of "improvement" of the human gene pool, such as what is a beneficial characteristic and what is a defect. Historically, this aspect of eugenics was tainted with scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

and pseudoscience.

Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with factors of perceived

Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with factors of perceived intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. More generally, it can b ...

that often correlated strongly with social class. These included Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson (; born Carl Pearson; 27 March 1857 – 27 April 1936) was an English mathematician and biostatistician. He has been credited with establishing the discipline of mathematical statistics. He founded the world's first university st ...

and Walter Weldon

Walter Weldon FRS FRSE (31 October 183220 September 1885) was a 19th-century English industrial chemist and journalist. He was President of the Society of Chemical Industry 1883/84.

Life

He was born in Loughborough on 31 October 1832, the son ...

, who worked on this at the University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

. In his lecture "Darwinism, Medical Progress and Eugenics", Pearson claimed that everything concerning eugenics fell into the field of medicine.

Eugenic policies have been conceptually divided into two categories. Positive eugenics is aimed at encouraging reproduction among the genetically advantaged; for example, the reproduction of the intelligent, the healthy, and the successful. Possible approaches include financial and political stimuli, targeted demographic analyses, ''in vitro'' fertilization, egg transplants, and cloning. Negative eugenics aimed to eliminate, through sterilization or segregation, those deemed physically, mentally, or morally "undesirable". This includes abortions, sterilization, and other methods of family planning. Both positive and negative eugenics can be coercive; in Nazi Germany, for example, abortion was illegal for women deemed by the state to be fit.

Controversy over scientific and moral legitimacy

Arguments for scientific validity

The first major challenge to conventional eugenics based on genetic inheritance was made in 1915 byThomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role tha ...

. He demonstrated the event of genetic mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitos ...

occurring outside of inheritance involving the discovery of the hatching of a fruit fly (''Drosophila melanogaster'') with white eyes from a family with red eyes, demonstrating that major genetic changes occurred outside of inheritance. Additionally, Morgan criticized the view that certain traits, such as intelligence and criminality, were hereditary because these traits were subjective. Despite Morgan's public rejection of eugenics, much of his genetic research was adopted by proponents of eugenics.

The heterozygote

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

is used for the early detection of recessive

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and t ...

hereditary diseases, allowing for couples to determine if they are at risk of passing genetic defects to a future child. The goal of the test is to estimate the likelihood of passing the hereditary disease to future descendants.

There are examples of eugenic acts that managed to lower the prevalence of recessive diseases, although not influencing the prevalence of heterozygote carriers of those diseases. The elevated prevalence of certain genetically transmitted diseases among the Ashkenazi Jew

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

ish population ( Tay–Sachs, cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a rare genetic disorder that affects mostly the lungs, but also the pancreas, liver, kidneys, and intestine. Long-term issues include difficulty breathing and coughing up mucus as a result of frequent lung infections. O ...

, Canavan's disease, and Gaucher's disease

Gaucher's disease or Gaucher disease () (GD) is a genetic disorder

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome. It can be caused by a mutation in a single gene (monogenic) or multiple genes (polyg ...

), has been decreased in current populations by the application of genetic screening.

Pleiotropy

Pleiotropy (from Greek , 'more', and , 'way') occurs when one gene influences two or more seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits. Such a gene that exhibits multiple phenotypic expression is called a pleiotropic gene. Mutation in a pleiotropic g ...

occurs when one gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

influences multiple, seemingly unrelated phenotypic trait

A phenotypic trait, simply trait, or character state is a distinct variant of a phenotypic characteristic of an organism; it may be either inherited or determined environmentally, but typically occurs as a combination of the two.Lawrence, Eleano ...

s, an example being phenylketonuria

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is an inborn error of metabolism that results in decreased metabolism of the amino acid phenylalanine. Untreated PKU can lead to intellectual disability, seizures, behavioral problems, and mental disorders. It may also resu ...

, which is a human disease that affects multiple systems but is caused by one gene defect. Andrzej Pękalski, from the University of Wrocław

, ''Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Breslau'' (before 1945)

, free_label = Specialty programs

, free =

, colors = Blue

, website uni.wroc.pl

The University of Wrocław ( pl, Uniwersytet Wrocławski, U ...

, argues that eugenics can cause harmful loss of genetic diversity if a eugenics program selects a pleiotropic gene that could possibly be associated with a positive trait. Pekalski uses the example of a coercive government eugenics program that prohibits people with myopia

Near-sightedness, also known as myopia and short-sightedness, is an eye disease where light focuses in front of, instead of on, the retina. As a result, distant objects appear blurry while close objects appear normal. Other symptoms may include ...

from breeding but has the unintended consequence of also selecting against high intelligence since the two go together.

Objections to scientific validity

Eugenic policies may lead to a loss ofgenetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

. Further, a culturally-accepted "improvement" of the gene pool may result in extinction, due to increased vulnerability to disease, reduced ability to adapt to environmental change, and other factors that may not be anticipated in advance. This has been evidenced in numerous instances, in isolated island populations. A long-term, species-wide eugenics plan might lead to such a scenario because the elimination of traits deemed undesirable would reduce genetic diversity by definition.

While the science of genetics has increasingly provided means by which certain characteristics and conditions can be identified and understood, given the complexity of human genetics, culture, and psychology, at this point there is no agreed objective means of determining which traits might be ultimately desirable or undesirable. Some conditions such as sickle-cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents. The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red blo ...

and cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a rare genetic disorder that affects mostly the lungs, but also the pancreas, liver, kidneys, and intestine. Long-term issues include difficulty breathing and coughing up mucus as a result of frequent lung infections. O ...

respectively confer immunity to malaria and resistance to cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

when a single copy of the recessive allele is contained within the genotype of the individual, so eliminating these genes is undesirable in places where such diseases are common.

Ethical controversies

Societal and political consequences of eugenics call for a place in the discussion on the ethics behind the eugenics movement. Many of the ethical concerns regarding eugenics arise from its controversial past, prompting a discussion on what place, if any, it should have in the future. Advances in science have changed eugenics. In the past, eugenics had more to do with sterilization and enforced reproduction laws. Now, in the age of a progressively mapped genome, embryos can be tested for susceptibility to disease, gender, and genetic defects, and alternative methods of reproduction such as in vitro fertilization are becoming more common. Therefore, eugenics is no longer ''ex post facto'' regulation of the living but instead preemptive action on the unborn. With this change, however, there are ethical concerns which some groups feel warrant more attention before this practice is commonly rolled out. Sterilized individuals, for example, could volunteer for the procedure, albeit under incentive or duress, or at least voice their opinion. The unborn fetus on which these new eugenic procedures are performed cannot speak out, as the fetus lacks the voice to consent or to express their opinion. Philosophers disagree about the proper framework for reasoning about such actions, which change the very identity and existence of future persons.Opposition

Edwin Black

Edwin Black (born February 27, 1950) is an American historian and author, as well as a syndicated columnist, investigative journalist, and weekly talk show host on The Edwin Black Show. He specializes in human rights, the historical interplay be ...

has described potential "eugenics wars" as the worst-case outcome of eugenics. In his view, this scenario would mean the return of coercive state-sponsored genetic discrimination

Genetic discrimination occurs when people treat others (or are treated) differently because they have or are perceived to have a gene mutation(s) that causes or increases the risk of an inherited disorder. It may also refer to any and all discri ...

and human rights violations

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hum ...

such as the compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually done throug ...

of persons with genetic defects, the killing of the institutionalized and, specifically, the segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

and genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

of races which are considered inferior. Law professors George Annas

George J. Annas is the William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor and Director of the Center for Health Law, Ethics & Human Rights at the Boston University School of Public Health, School of Medicine, and School of Law.

Biography

Annas h ...

and Lori Andrews

Lori B. Andrews is an American professor of law. She is on the faculty of Illinois Institute of Technology Chicago-Kent College of Law and serves as Director of IIT's Institute for Science, Law, and Technology. In 2002, she was a visiting professo ...

have argued that the use of these technologies could lead to such human-posthuman

Posthuman or post-human is a concept originating in the fields of science fiction, futurology, contemporary art, and philosophy that means a person or entity that exists in a state beyond being human. The concept aims at addressing a variety of ...

caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultura ...

warfare.

Environmental ethicist Bill McKibben

William Ernest McKibben (born December 8, 1960)"Bill Ernest McKibben." ''Environmental Encyclopedia''. Edited by Deirdre S. Blanchfield. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, 2009. Retrieved via ''Biography in Context'' database, December 31, 2017. is a ...

argued against germinal choice technology

Germinal may refer to:

*Germinal (French Republican Calendar), the seventh month of the calendar, approximately March 21 - April 19

Émile Zola

* ''Germinal'' (novel), an 1885 novel by Émile Zola

** ''Germinal'' (1913 film), a French silent film ...

and other advanced biotechnological strategies for human enhancement. He writes that it would be morally wrong for humans to tamper with fundamental aspects of themselves (or their children) in an attempt to overcome universal human limitations, such as vulnerability to aging

Ageing ( BE) or aging ( AE) is the process of becoming older. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi, whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentially biologically immortal. In ...

, maximum life span

Maximum life span (or, for humans, maximum reported age at death) is a measure of the maximum amount of time one or more members of a population have been observed to survive between birth and death. The term can also denote an estimate of the max ...

and biological constraints on physical and cognitive ability. Attempts to "improve" themselves through such manipulation would remove limitations that provide a necessary context for the experience of meaningful human choice. He claims that human lives would no longer seem meaningful in a world where such limitations could be overcome with technology. Even the goal of using germinal choice technology for clearly therapeutic purposes should be relinquished, he argues, since it would inevitably produce temptations to tamper with such things as cognitive capacities. He argues that it is possible for societies to benefit from renouncing particular technologies, using Ming China

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peop ...

, Tokugawa Japan

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional ''daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characterize ...

and the contemporary Amish

The Amish (; pdc, Amisch; german: link=no, Amische), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptist Christian church fellowships with Swiss German and Alsatian origins. They are closely related to Mennonite churches ...

as examples.

Endorsement

Some, for exampleNathaniel C. Comfort

Nathaniel Charles Comfort is an American historian specializing in the history of biology. He is an associate professor in the Institute of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University. In 2015, he was appointed the third Baruch S. Blumbe ...

from Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hem ...

, claim that the change from state-led reproductive-genetic decision-making to individual choice has moderated the worst abuses of eugenics by transferring the decision-making process from the state to patients and their families. Comfort suggests that "the eugenic impulse drives us to eliminate disease, live longer and healthier, with greater intelligence, and a better adjustment to the conditions of society; and the health benefits, the intellectual thrill and the profits of genetic bio-medicine are too great for us to do otherwise." Others, such as bioethicist

Bioethics is both a field of study and professional practice, interested in ethical issues related to health (primarily focused on the human, but also increasingly includes animal ethics), including those emerging from advances in biology, med ...

Stephen Wilkinson of Keele University

Keele University, officially known as the University of Keele, is a public research university in Keele, approximately from Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, England. Founded in 1949 as the University College of North Staffordshire, Keele ...

and Honorary Research Fellow Eve Garrard at the University of Manchester

, mottoeng = Knowledge, Wisdom, Humanity

, established = 2004 – University of Manchester Predecessor institutions: 1956 – UMIST (as university college; university 1994) 1904 – Victoria University of Manchester 1880 – Victoria Univer ...