Eugene Lanceray on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Yevgeny Yevgenyevich Lanceray (russian: Евгений Евгеньевич Лансере; 23 August 1875 – 13 September 1946), also often spelled Eugene Lansere, was a Russian graphic artist, painter, sculptor,

Yevgeny Yevgenyevich Lanceray (russian: Евгений Евгеньевич Лансере; 23 August 1875 – 13 September 1946), also often spelled Eugene Lansere, was a Russian graphic artist, painter, sculptor,

Eugeny Alexandrovich Lanceray

was a sculptor. His grandfather

One of the most well-known works of Lanceray is the mural of Kazanskiy Railway Station (1932-1934 and 1944-1946).

Schusev, the famous Russian architect and a frequent character of Lanceray's diaries, was responsible for the whole process from the very beginning. In 1916, Schusev, Benois,

One of the most well-known works of Lanceray is the mural of Kazanskiy Railway Station (1932-1934 and 1944-1946).

Schusev, the famous Russian architect and a frequent character of Lanceray's diaries, was responsible for the whole process from the very beginning. In 1916, Schusev, Benois,  1932 was the year when the state reform of architecture was carried out in the USSR, and ‘Stalinist’ architecture with its monumental style became canonical. Lanceray, an experienced monumental painter with conservative views, was invited from

1932 was the year when the state reform of architecture was carried out in the USSR, and ‘Stalinist’ architecture with its monumental style became canonical. Lanceray, an experienced monumental painter with conservative views, was invited from Е.Е.Лансере. Казанский вокзал.

Boris (byk). E.E.Lanceray. Kazanskiy vokzal. E.E.Lanceray. Kazanskiy Railway Station(accessed: 28.02.2020) (in Russ.).'']

Because of the irregular construction of the building, high ceilings and unpredictable light, the artist faced difficulties to make the painting bright and noticeable. Besides its place and its scale, a distinctive feature of this work is that it was made using tempera paint. The artist also preferred to paint on a canvas that would then be attached to the ceiling. But, while Lanceray was disappointed with his inappropriate use of technique, the Committee members were not really satisfied with the subject of Lanceray's paintings.

Later, they would say that his projects were missing a “deep socialist” idea in his projects and would blame him for using too many abstract symbols and allegories.

Lanceray kept working on these monumental paintings after the war finished. After his death, other artists had to finish the work according to the sketches he left.

Nowadays the decorated plafond of Kazanskiy railway station looks very contrast. Heavy soviet paintings of predominantly brown shades seem lost among pompous gilded stucco molding.

Today this part of the building is used as a superior lounge, where people who buy business class tickets can wait for their departure. On every New Year's Eve, there is a constructed stage where children's performances are shown and music concerts are played.

Biography

The Grove Dictionary of Art

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lanceray, Eugene 19th-century painters from the Russian Empire Russian male painters 20th-century Russian painters 1875 births 1946 deaths Painters from Saint Petersburg Stalin Prize winners Académie Julian alumni Académie Colarossi alumni Benois family Tbilisi State Academy of Arts faculty Russian people of French descent

Yevgeny Yevgenyevich Lanceray (russian: Евгений Евгеньевич Лансере; 23 August 1875 – 13 September 1946), also often spelled Eugene Lansere, was a Russian graphic artist, painter, sculptor,

Yevgeny Yevgenyevich Lanceray (russian: Евгений Евгеньевич Лансере; 23 August 1875 – 13 September 1946), also often spelled Eugene Lansere, was a Russian graphic artist, painter, sculptor, mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

ist, and illustrator, associated stylistically with ''Mir iskusstva'' ( the World of Art).Scholl, Tim. "From Petipa to Balanchine: Classical Revival and the Modernization of Ballet", page 144. London: Routledge, 1994.

Early life and education

Lanceray was born in Pavlovsk, Russia, a suburb ofSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. He came from a prominent Russian artistic family of French origin.Chilvers, Ian. "A Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Art", p. 560. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. His fatherEugeny Alexandrovich Lanceray

was a sculptor. His grandfather

Nicholas Benois

Nicholas Benois (russian: link=no, Никола́й Лео́нтьевич Бенуа́; 13 July 1813 – 23 December 1898) was an Imperial Russian architect who worked in Petergof, Peterhof and other suburbs of St Petersburg.

Biography

Benois w ...

, and his uncle Leon Benois

Leon Benois (russian: Леонтий Николаевич Бенуа; 1856 in Peterhof – 1928 in Leningrad) was a Russian architect from the Benois family.

Biography

He was the son of architect Nicholas Benois, the brother of artists Alexandr ...

, were celebrated architects. Another uncle, Alexandre Benois

Alexandre Nikolayevich Benois (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Бенуа́, also spelled Alexander Benois; ,Salmina-Haskell, Larissa. ''Russian Paintings and Drawings in the Ashmolean Museum''. pp. 15, 23-24. Published by ...

, was a respected artist, art critic, historian and preservationist. His great-grandfather was Venetian-born Russian composer Catterino Cavos

Catterino Albertovich Cavos (: Catarino Camillo Cavos; russian: Катери́но Альбе́ртович Ка́вос) (October 30, 1775 – May 10 ( OS April 28), 1840), born Catarino Camillo Cavos, was an Italian composer, organist and co ...

. Lanceray's siblings were also heirs to this artistic tradition. His sister, Zinaida Serebriakova

Zinaida Yevgenyevna Serebriakova (russian: Зинаида Евгеньевна Серебрякова; – 20 September 1967) was a Russian and later French painter.

Family

Zinaida Serebryakova was born on the estate of Neskuchnoye near Kh ...

, was a painter, while his brother Nikolay was an architect. His cousin, Nadia Benois

Nadezhda Leontievna Ustinova (russian: Надежда Леонтьевна Устинова; 27 April 18968 December 1975), née ''Benois'' (Бенуа), better known as Nadia Benois, was a Russian-born painter of still lifes and landscapes, and ...

, was mother of Peter Ustinov

Sir Peter Alexander Ustinov (born Peter Alexander Freiherr von Ustinov ; 16 April 192128 March 2004) was a British actor, filmmaker and writer. An internationally known raconteur, he was a fixture on television talk shows and lecture circuits ...

.

His father Eugene Lanceray, who was also an artist, died early, aged forty; when the boy was eleven years old. However, his father's example, memories of everything that was connected with his life and work affected the formation of the personality of the future artist. Already a mature and experienced master, Eugene Lanceray noted that “his search for the right everyday gesture, interest in the ethnographic characterization of characters”, and, finally, “attraction to the Caucasus” were received from his father “as a heredity” characteristic of his work.

The artist spent his childhood in Ukraine, in a small estate of his father Neskuchnoe.

After the death of Eugene Lanceray, the artist's father, mother moved with her children to St. Petersburg, to his father's house, known in art circles as “the house of Benois near Nikola Morskoy” (russian: Дом Бенуа у Николы Морского).

Lanceray took his first lessons at the Drawing School of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts

The Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts (Russian: Императорское общество поощрения художеств (ОПХ)) was an organization devoted to promoting the arts that existed in Saint Petersburg from 182 ...

in St. Petersburg from 1892 to 1896.Bown, Matthew Cullerne. "Art Under Stalin", p. 243. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1991. under Jan Ciągliński and Ernst Friedrich von Liphart

Baron Ernst Friedrich von Liphart (1847–1932), Russified as Ernst Karlovich Lipgart and also referred to in English as Earnest Lipgart, was a painter, a noted art expert and art collector from what is now Tartu in Estonia. After living for a t ...

. He then traveled to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, where he continued his studies at the Académie Colarossi

The Académie Colarossi (1870–1930) was an art school in Paris founded in 1870 by the Italian model and sculptor Filippo Colarossi. It was originally located on the Île de la Cité, and it moved in 1879 to 10 rue de la Grande-Chaumière in the ...

and Académie Julian

The Académie Julian () was a private art school for painting and sculpture founded in Paris, France, in 1867 by French painter and teacher Rodolphe Julian (1839–1907) that was active from 1868 through 1968. It remained famous for the number a ...

between 1896 and 1899.

Career before the revolution

After returning from France to Russia, Lanceray joined ''Mir iskusstva

''Mir iskusstva'' ( rus, «Мир искусства», p=ˈmʲir ɪˈskustvə, ''World of Art'') was a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it inspired and embodied, which was a major influence on the Russians who helped revolutionize Eur ...

'', an influential Russian art movement inspired by an artistic journal

A journal, from the Old French ''journal'' (meaning "daily"), may refer to:

*Bullet journal, a method of personal organization

*Diary, a record of what happened over the course of a day or other period

*Daybook, also known as a general journal, a ...

of the same name, founded in 1899, in Saint Petersburg. Other prominent members of ''Mir iskusstva

''Mir iskusstva'' ( rus, «Мир искусства», p=ˈmʲir ɪˈskustvə, ''World of Art'') was a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it inspired and embodied, which was a major influence on the Russians who helped revolutionize Eur ...

included Lanceray's uncle Alexandre Benois

Alexandre Nikolayevich Benois (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Бенуа́, also spelled Alexander Benois; ,Salmina-Haskell, Larissa. ''Russian Paintings and Drawings in the Ashmolean Museum''. pp. 15, 23-24. Published by ...

, Konstantin Somov

Konstantin Andreyevich Somov (russian: Константин Андреевич Сомов; November 30, 1869 – May 6, 1939) was a Russian artist associated with the ''Mir iskusstva''.

Biography Early life

Konstantin Somov was born on ...

, Walter Nouvel

Walter Feodorovich Nouvel (russian: Вальтер Федорович Нувель) (1871–1949) was a Russian émigré art-lover and writer. He co-wrote with Arnold Haskell a biography of Sergei Pavlovitch Diaghilev (''Diaghileff. His Artisti ...

, Léon Bakst

Léon Bakst (russian: Леон (Лев) Николаевич Бакст, Leon (Lev) Nikolaevich Bakst) – born as Leyb-Khaim Izrailevich (later Samoylovich) Rosenberg, Лейб-Хаим Израилевич (Самойлович) Розенбе ...

, and Dmitry Filosofov.

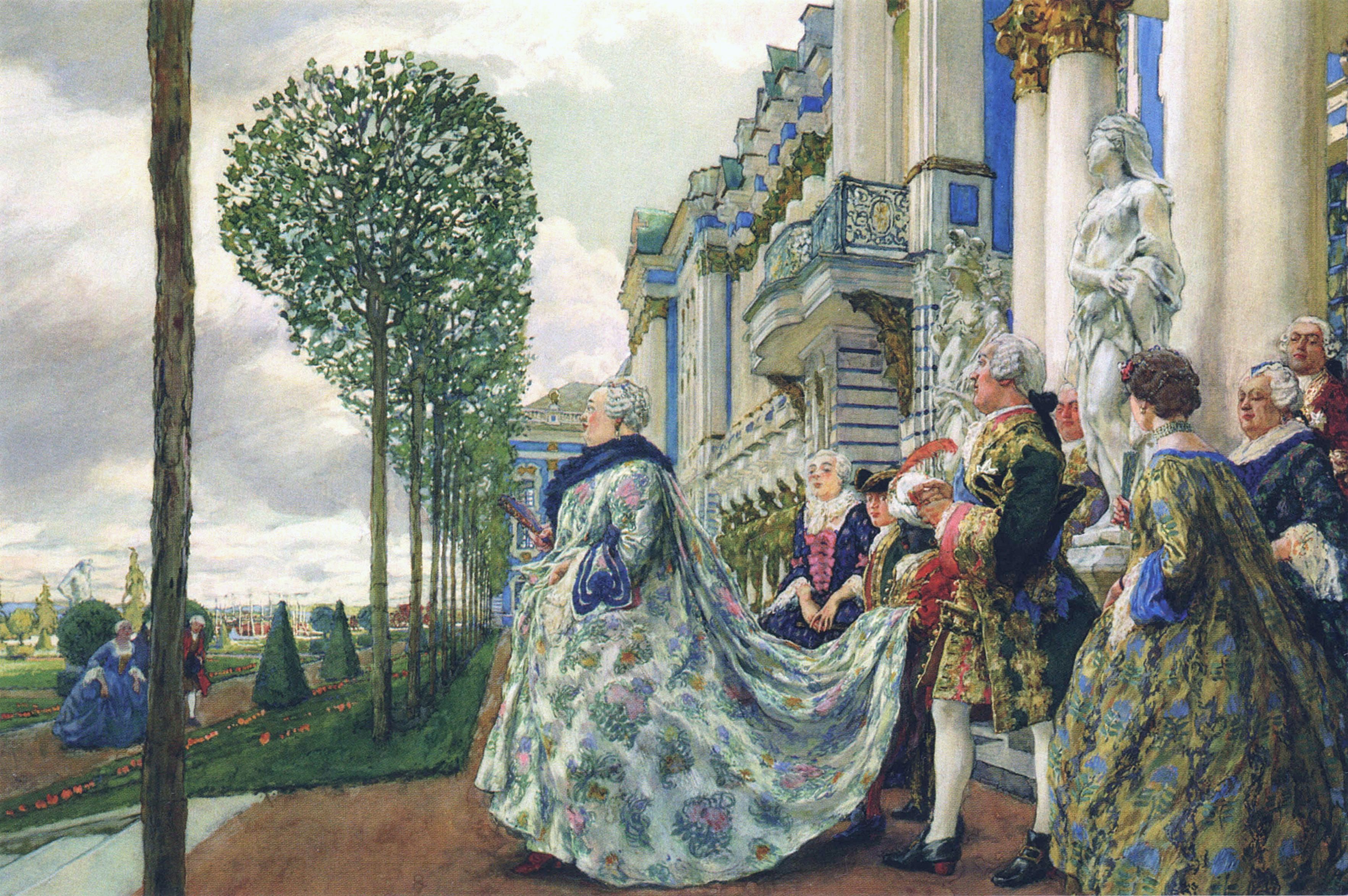

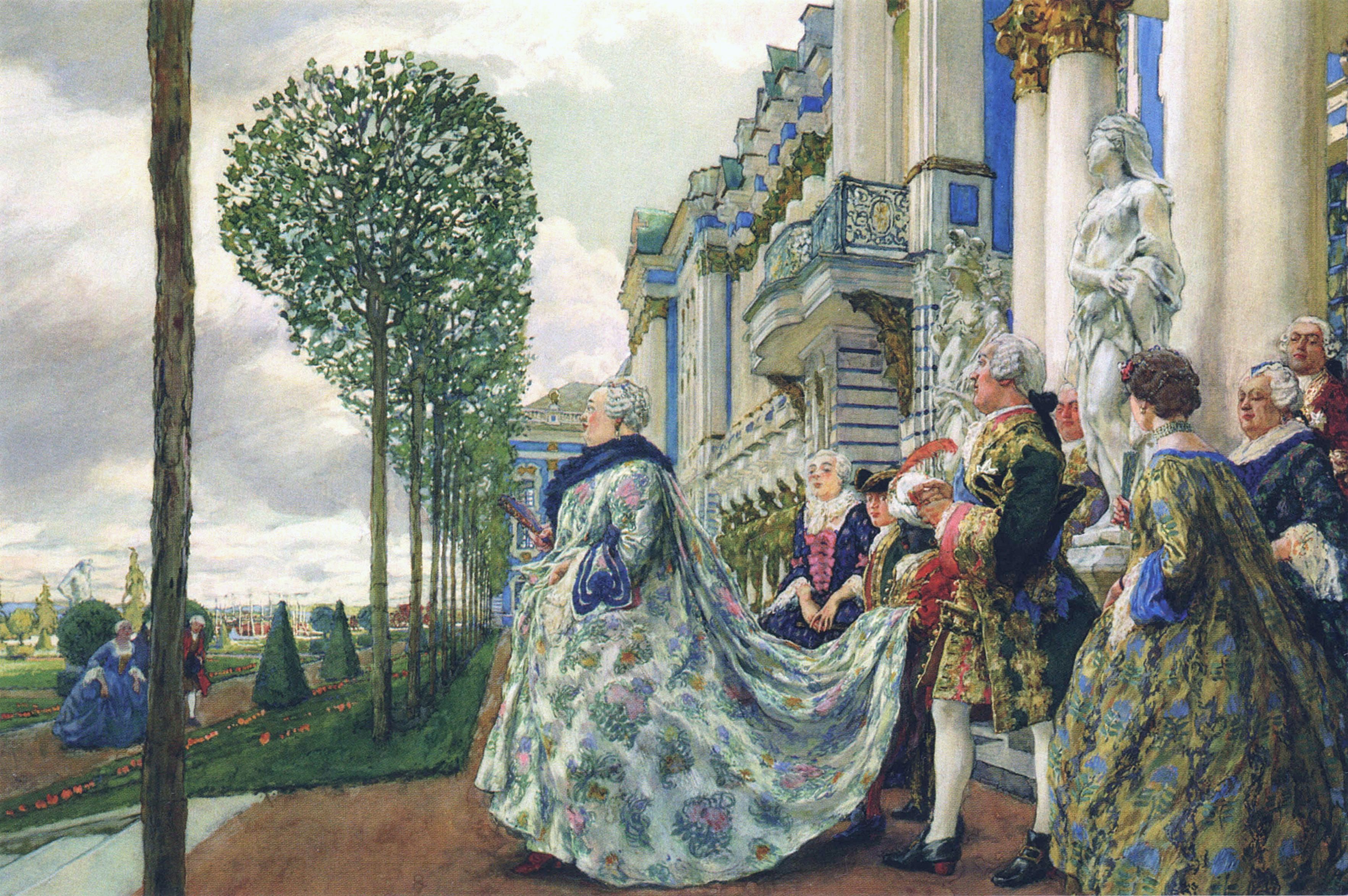

Like other members of ''Mir iskusstva

''Mir iskusstva'' ( rus, «Мир искусства», p=ˈmʲir ɪˈskustvə, ''World of Art'') was a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it inspired and embodied, which was a major influence on the Russians who helped revolutionize Eur ...

'', he was fascinated with the "sparkling dust" of Rococo

Rococo (, also ), less commonly Roccoco or Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and theatrical style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpted moulding, ...

art, and often turned to the 18th-century Russian history and art for inspiration.

Eugene Lanceray was younger than the masters of ''Mir iskusstva

''Mir iskusstva'' ( rus, «Мир искусства», p=ˈmʲir ɪˈskustvə, ''World of Art'') was a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it inspired and embodied, which was a major influence on the Russians who helped revolutionize Eur ...

'' and initially acted as their student. His creative method and aesthetic views evolved under the influence and guidance of Benois, although, by some aspects of his talent, Lanceray may have exceeded his teacher. His first significant works in the field of easel painting and graphics were created in the late 1890 - early 1900s. The main creative interests of the artist were turned at that time to the "historical", mainly architectural landscape.

Lanceray's most celebrated mural painting is located at the ceiling of Moscow Kazansky railway station

Kazansky railway terminal (russian: Каза́нский вокза́л, ''Kazansky vokzal'') also known as Moscow Kazansky railway station (russian: Москва́-Каза́нская, ''Moskva-Kazanskaya'') is one of nine railway terminals in ...

(1933-1934). Besides its place and its scale, the distinctive feature of this work is that it was made using tempera paint, so beloved by the artist. But he worked with various media, and the area of his activity included not only mural art but also fine art, graphics, illustration and theatrical scenery. For the first time, Lanceray took to the work in the theater in early 1900s, paying tribute to the passion for theater painting, which was characteristic of almost all the representatives of the older generation of the ''Mir iskusstva

''Mir iskusstva'' ( rus, «Мир искусства», p=ˈmʲir ɪˈskustvə, ''World of Art'') was a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it inspired and embodied, which was a major influence on the Russians who helped revolutionize Eur ...

'' group.

Life after the revolution

Lanceray was the only prominent member of ''Mir iskusstva

''Mir iskusstva'' ( rus, «Мир искусства», p=ˈmʲir ɪˈskustvə, ''World of Art'') was a Russian magazine and the artistic movement it inspired and embodied, which was a major influence on the Russians who helped revolutionize Eur ...

'' to remain in Russia after the Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

. Being a representative of traditional painting (not avant-garde movement) and the bourgeoisie, he was not in great demand with the new Soviet government for a long time. Even his sister found the revolutionary milieu alien to her art and, in 1924, she fled to Paris.

Lanceray himself hated the new Soviet regime that he had to exist in after 1917. It referred to his own understanding of the historical way of Russia and the massive oppressions towards his relatives and close friends (some of them immigrated and some of them were killed). In February 1932 he left a note in his diaries: ‘There is incredible impoverishment. Of course, this is the government’s goal to bring everyone and everything to poverty, since it is easier to manage the poor and the hungry’.

Lanceray left Saint Petersburg in 1917, and spent three years living in Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; rus, Дагеста́н, , dəɡʲɪˈstan, links=yes), officially the Republic of Dagestan (russian: Респу́блика Дагеста́н, Respúblika Dagestán, links=no), is a republic of Russia situated in the North C ...

, where he became infatuated with Oriental

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of ''Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the ...

themes. His interest increased during journeys made in the early 1920s to Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

and Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, maki ...

, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

. In 1920, he moved to Tiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million pe ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. During his stay in Georgia, he lectured at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts

The Tbilisi State Academy of Arts ( ka, თბილისის სახელმწიფო სამხატვრო აკადემია) is one of the oldest universities in Georgia and Caucasus. It is located in central Tbilisi near ...

(1922–1934) and illustrated the Caucasian novellas of Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

. Amongst his students was Apollon Kutateladze

Apollon Karamanovich Kutateladze (in Georgian language, Georgian: , in Khoni – in Tbilisi) was a Soviet and Georgian Painting, painter.

Early life

Apollon Kutateladze started to study in Poti, Georgia (country), Georgia. He continued to st ...

.

Lanceray left Georgia in 1934, settling in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, where he became engaged in the decoration of the Moscow Kazansky railway station

Kazansky railway terminal (russian: Каза́нский вокза́л, ''Kazansky vokzal'') also known as Moscow Kazansky railway station (russian: Москва́-Каза́нская, ''Moskva-Kazanskaya'') is one of nine railway terminals in ...

and the Hotel Moskva. During the same period, Lanceray also worked as a theatrical designer.

Three years before his death, he was honored with the Stalin Prize Stalin Prize may refer to:

* The State Stalin Prize in science and engineering and in arts, awarded 1941 to 1954, later known as the USSR State Prize

The USSR State Prize (russian: links=no, Государственная премия СССР, ...

, and in 1945 he was awarded the title of the People's Artist of the RSFSR. He died in Moscow at the age of 71.

Moscow Kazansky Railway Station

One of the most well-known works of Lanceray is the mural of Kazanskiy Railway Station (1932-1934 and 1944-1946).

Schusev, the famous Russian architect and a frequent character of Lanceray's diaries, was responsible for the whole process from the very beginning. In 1916, Schusev, Benois,

One of the most well-known works of Lanceray is the mural of Kazanskiy Railway Station (1932-1934 and 1944-1946).

Schusev, the famous Russian architect and a frequent character of Lanceray's diaries, was responsible for the whole process from the very beginning. In 1916, Schusev, Benois, Serebryakova Serebryakov or Serebriakov (russian: Серебряков) is a Russian masculine surname originating from the word ''serebryak'', meaning ''silversmith''; its feminine counterpart is Serebryakova or Serebriakova. Notable persons with the surname in ...

, Lanceray were hired to plan the decorations and paintings for the Kazanskiy railway station, but the revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

broke off the plans.

1932 was the year when the state reform of architecture was carried out in the USSR, and ‘Stalinist’ architecture with its monumental style became canonical. Lanceray, an experienced monumental painter with conservative views, was invited from

1932 was the year when the state reform of architecture was carried out in the USSR, and ‘Stalinist’ architecture with its monumental style became canonical. Lanceray, an experienced monumental painter with conservative views, was invited from Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the Capital city, capital and the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia, lying on the ...

to Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

to continue working at The Central Railway Station decorations. He was in charge of the restaurant located inside.

In the 1932-1934 paintings, Lanceray tried to show specific features of every painted region. For instance, ''Murmansk'' displays a busy crew ship, while ''Crimea'' is depicted by a smiling Tatar woman against the background of a clear sky, exotic trees and a working carpenter.

In the thirties, he managed to complete such murals as ''Moscow Construction, Murmansk, Crimea,'' and others. In January 1934, after gluing the first canvas to the plafond Lanceray writes:

''″A turning, formidable day: today they glued the first picture, Crimea. Of course, I am shocked by the effect. It is small, puny, completely not picturesque, completely not monumental. <..> At this distance, there is no other volumetric effect <..> That's when you learn the experience and mastery of Byzantium!″Boris (byk). E.E.Lanceray. Kazanskiy vokzal. E.E.Lanceray. Kazanskiy Railway Station(accessed: 28.02.2020) (in Russ.).'']

Mural artworks in Kharkiv

In 1932, Lanceray completed two of his monumental works at the ZheleznodorozhnikPalace of Culture

Palace of Culture (russian: Дворец культуры, dvorets kultury, , ''wénhuà gōng'', german: Kulturpalast) or House of Culture (Polish: ''dom kultury'') is a common name (generic term) for major Club (organization), club-houses (comm ...

(now "the Central House of Culture and Technology of the South Railway") in Kharkiv. One of them is called ''Partisans of the Caucasus salute the Red Army'' and the other one ''Meeting of Komsomol members with the peasants of Crimea''.

Over time, the paintings deteriorated and were often hidden behind a cloth. In connection with the Euro-2012, they were restored. These two murals are the only monumental works of Eugene Lanceray preserved in Ukraine and the only examples of murals of the 1930s that exist in Kharkiv. Although there were a lot of wall paintings in Kharkiv in the pre-war period, almost all of them either died during the war or disappeared during repairs, or were deliberately destroyed.

After the adoption of the Law of Decommunization in Ukraine in 2015, these murals painted by Lanceray in Kharkiv were at risk of destruction. A public discussion was held on the conservation of them. Since the work could not be visually construed as direct communist propaganda, officials asked the state to give it the status of cultural heritage.

If approved, these artworks of Lanceray would be the first examples of monumental painting, which the Ukrainian state will protect.

See also

*List of Russian artists

This is a list of Russians artists. In this context, the term "Russian" covers the Russian Federation, Soviet Union, Russian Empire, Tsardom of Russia and Grand Duchy of Moscow, including ethnic Russians and people of other ethnicities living in Ru ...

* Kasli iron sculpture

Kasli cast-iron sculpture was produced in Kasli (Southern Ural), from the mid-19th century. A large collection, including an elaborate pavilion from the 1900 Paris World Fair, is displayed in the Yekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts. There is also a ...

References

External links

*Biography

The Grove Dictionary of Art

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lanceray, Eugene 19th-century painters from the Russian Empire Russian male painters 20th-century Russian painters 1875 births 1946 deaths Painters from Saint Petersburg Stalin Prize winners Académie Julian alumni Académie Colarossi alumni Benois family Tbilisi State Academy of Arts faculty Russian people of French descent