Escherichia Coli (MCC) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Escherichia coli'' ()Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a

A common subdivision system of ''E. coli'', but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface

A common subdivision system of ''E. coli'', but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface

Like all lifeforms, new strains of ''E. coli'' evolve through the natural biological processes of

Like all lifeforms, new strains of ''E. coli'' evolve through the natural biological processes of  In the microbial world, a relationship of predation can be established similar to that observed in the animal world. Considered, it has been seen that ''E. coli'' is the prey of multiple generalist predators, such as ''

In the microbial world, a relationship of predation can be established similar to that observed in the animal world. Considered, it has been seen that ''E. coli'' is the prey of multiple generalist predators, such as ''

Gram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall ...

, facultative anaerobic

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are '' Staphylococc ...

, rod-shaped

A bacillus (), also called a bacilliform bacterium or often just a rod (when the context makes the sense clear), is a rod-shaped bacterium or archaeon. Bacilli are found in many different taxonomic groups of bacteria. However, the name ''Bacillu ...

, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escherichia

''Escherichia'' () is a genus of Gram-negative, non- spore-forming, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria from the family Enterobacteriaceae. In those species which are inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tracts of warm-blooded animals, ...

'' that is commonly found in the lower intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

of warm-blooded

Warm-blooded is an informal term referring to animal species which can maintain a body temperature higher than their environment. In particular, homeothermic species maintain a stable body temperature by regulating metabolic processes. The onl ...

organisms. Most ''E. coli'' strains are harmless, but some serotype

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or cells are classified together based on their surface antigens, allowing the epi ...

s such as EPEC, and ETEC are pathogenic and can cause serious food poisoning

Foodborne illness (also foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the spoilage of contaminated food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites that contaminate food,

as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disease) ...

in their hosts, and are occasionally responsible for food contamination

Food contamination refers to the presence of harmful chemicals and microorganisms in food, which can cause consumer illness. This article addresses the chemical contamination of foods, as opposed to microbiological contamination, which can be found ...

incidents that prompt product recalls. Most strains are part of the normal microbiota of the gut and are harmless or even beneficial to humans (although these strains tend to be less studied than the pathogenic ones). For example, some strains of ''E. coli'' benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K2 or by preventing the colonization of the intestine by pathogenic bacteria

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and are often Probiotic, beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The n ...

. These mutually beneficial relationships between ''E. coli'' and humans are a type of mutualistic biological relationship — where both the humans and the ''E. coli'' are benefitting each other. ''E. coli'' is expelled into the environment within fecal matter. The bacterium grows massively in fresh fecal matter under aerobic conditions for three days, but its numbers decline slowly afterwards.

''E. coli'' and other facultative anaerobes

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

constitute about 0.1% of gut microbiota

Gut microbiota, gut microbiome, or gut flora, are the microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses that live in the digestive tracts of animals. The gastrointestinal metagenome is the aggregate of all the genomes of the gut m ...

, and fecal–oral transmission is the major route through which pathogenic strains of the bacterium cause disease. Cells are able to survive outside the body for a limited amount of time, which makes them potential indicator organism

Indicator organisms are used as a proxy to monitor conditions in a particular environment, ecosystem, area, habitat, or consumer product. Certain bacteria, fungi and helminth eggs are being used for various purposes.

Types Indicator bacteria

...

s to test environmental samples for fecal contamination. A growing body of research, though, has examined environmentally persistent ''E. coli'' which can survive for many days and grow outside a host.

The bacterium can be grown and cultured easily and inexpensively in a laboratory setting, and has been intensively investigated for over 60 years. ''E. coli'' is a chemoheterotroph

A Chemotroph is an organism that obtains energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments. These molecules can be organic molecule, organic (chemoorganotrophs) or inorganic compound, inorganic (chemolithotrophs). The chemotroph de ...

whose chemically defined medium must include a source of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

and energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of heat a ...

. ''E. coli'' is the most widely studied prokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a Unicellular organism, single-celled organism that lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:πρό#Ancient Greek, πρό (, 'before') a ...

model organism

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workin ...

, and an important species in the fields of biotechnology

Biotechnology is the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services. The term ''biotechnology'' was first used b ...

and microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

, where it has served as the host organism

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasite, parasitic, a mutualism (biology), mutualistic, or a commensalism, commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with ...

for the majority of work with recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be foun ...

. Under favourable conditions, it takes as little as 20 minutes to reproduce.

Biology and biochemistry

Type and morphology

''E. coli'' is aGram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall ...

, facultative anaerobe

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

, nonsporulating coliform bacterium. Cells are typically rod-shaped, and are about 2.0 μm long and 0.25–1.0 μm in diameter, with a cell volume of 0.6–0.7 μm3.

''E. coli'' stains Gram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall ...

because its cell wall is composed of a thin peptidoglycan layer

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like peptidoglycan layer outside the plasma membrane, the rigid cell wall (murein sacculus) characteristic of most ba ...

and an outer membrane. During the staining process, ''E. coli'' picks up the color of the counterstain safranin

Safranin (Safranin O or basic red 2) is a biological stain used in histology and cytology. Safranin is used as a counterstain in some staining protocols, colouring cell nuclei red. This is the classic counterstain in both Gram stains and endospo ...

and stains pink. The outer membrane surrounding the cell wall provides a barrier to certain antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention o ...

such that ''E. coli'' is not damaged by penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' moulds, principally '' P. chrysogenum'' and '' P. rubens''. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum using ...

.

The flagella

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

which allow the bacteria to swim have a peritrichous arrangement. It also attaches and effaces to the microvilli of the intestines via an adhesion molecule

Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) are a subset of cell surface proteins that are involved in the binding of cells with other cells or with the extracellular matrix (ECM), in a process called cell adhesion. In essence, CAMs help cells stick to each ...

known as intimin

Intimin is a virulence factor ( adhesin) of EPEC (''e.g.'' ''E. coli'' O127:H6) and EHEC (''e.g. E. coli'' O157:H7) ''E. coli'' strains. It is an attaching and effacing (A/E) protein, which with other virulence factors is necessary and responsi ...

.

Metabolism

''E. coli'' can live on a wide variety of substrates and usesmixed acid fermentation

In biochemistry, mixed acid fermentation is the metabolic process by which a six-carbon sugar (e.g. glucose, ) is converted into a complex and variable mixture of acids. It is an anaerobic (non-oxygen-requiring) fermentation reaction that is ...

in anaerobic conditions, producing lactate, succinate

Succinic acid () is a dicarboxylic acid with the chemical formula (CH2)2(CO2H)2. The name derives from Latin ''succinum'', meaning amber. In living organisms, succinic acid takes the form of an anion, succinate, which has multiple biological ro ...

, ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl ...

, acetate

An acetate is a salt (chemistry), salt formed by the combination of acetic acid with a base (e.g. Alkali metal, alkaline, Alkaline earth metal, earthy, Transition metal, metallic, nonmetallic or radical Radical (chemistry), base). "Acetate" als ...

, and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

. Since many pathways in mixed-acid fermentation produce hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

gas, these pathways require the levels of hydrogen to be low, as is the case when ''E. coli'' lives together with hydrogen-consuming organisms, such as methanogen

Methanogens are microorganisms that produce methane as a metabolic byproduct in hypoxic conditions. They are prokaryotic and belong to the domain Archaea. All known methanogens are members of the archaeal phylum Euryarchaeota. Methanogens are com ...

s or sulphate-reducing bacteria.

In addition, ''E. coli''s metabolism can be rewired to solely use CO2 as the source of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

for biomass production. In other words, this obligate heterotroph's metabolism can be altered to display autotrophic capabilities by heterologously expressing carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation or сarbon assimilation is the process by which inorganic carbon (particularly in the form of carbon dioxide) is converted to organic compounds by living organisms. The compounds are then used to store energy and as ...

genes as well as formate dehydrogenase

Formate dehydrogenases are a set of enzymes that catalyse the oxidation of formate to carbon dioxide, donating the electrons to a second substrate, such as NAD+ in formate:NAD+ oxidoreductase () or to a cytochrome in formate:ferricytochrome-b1 o ...

and conducting laboratory evolution experiments. This may be done by using formate

Formate (IUPAC name: methanoate) is the conjugate base of formic acid. Formate is an anion () or its derivatives such as ester of formic acid. The salts and esters are generally colorless.Werner Reutemann and Heinz Kieczka "Formic Acid" in ''Ull ...

to reduce electron carriers and supply the ATP required in anabolic pathways inside of these synthetic autotrophs.

''E. coli'' has three native glycolytic pathways: EMPP, EDP, and OPPP. The EMPP employs ten enzymatic steps to yield two pyruvates, two ATP, and two NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an aden ...

per glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

molecule while OPPP serves as an oxidation route for NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, abbreviated NADP or, in older notation, TPN (triphosphopyridine nucleotide), is a cofactor used in anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses, which require NAD ...

synthesis. Although the EDP is the more thermodynamically favourable of the three pathways, ''E. coli'' do not use the EDP for glucose metabolism

Carbohydrate metabolism is the whole of the biochemical processes responsible for the metabolic formation, breakdown, and interconversion of carbohydrates in living organisms.

Carbohydrates are central to many essential metabolic pathways. Plants ...

, relying mainly on the EMPP and the OPPP. The EDP mainly remains inactive except for during growth with gluconate

Gluconic acid is an organic compound with molecular formula C6H12O7 and condensed structural formula HOCH2(CHOH)4COOH. It is one of the 16 stereoisomers of 2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxyhexanoic acid.

In aqueous solution at neutral pH, gluconic acid fo ...

.

Catabolite repression

When growing in the presence of a mixture of sugars, bacteria will often consume the sugars sequentially through a process known as catabolite repression. By repressing the expression of the genes involved in metabolizing the less preferred sugars, cells will usually first consume the sugar yielding the highest growth rate, followed by the sugar yielding the next highest growth rate, and so on. In doing so the cells ensure that their limited metabolic resources are being used to maximize the rate of growth. The well-used example of this with ''E. coli'' involves the growth of the bacterium onglucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

and lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide sugar synthesized by galactose and glucose subunits and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from ' (gen. '), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix '' - ...

, where ''E. coli'' will consume glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

before lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide sugar synthesized by galactose and glucose subunits and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from ' (gen. '), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix '' - ...

. Catabolite repression has also been observed in ''E. coli'' in the presence of other non-glucose sugars, such as arabinose

Arabinose is an aldopentose – a monosaccharide containing five carbon atoms, and including an aldehyde (CHO) functional group.

For biosynthetic reasons, most saccharides are almost always more abundant in nature as the "D"-form, or structurally ...

and xylose

Xylose ( grc, ξύλον, , "wood") is a sugar first isolated from wood, and named for it. Xylose is classified as a monosaccharide of the aldopentose type, which means that it contains five carbon atoms and includes an aldehyde functional gro ...

, sorbitol

Sorbitol (), less commonly known as glucitol (), is a sugar alcohol with a sweet taste which the human body metabolizes slowly. It can be obtained by reduction of glucose, which changes the converted aldehyde group (−CHO) to a primary alcohol g ...

, rhamnose

Rhamnose (Rha, Rham) is a naturally occurring deoxy sugar. It can be classified as either a methyl-pentose or a 6-deoxy-hexose. Rhamnose predominantly occurs in nature in its L-form as L-rhamnose (6-deoxy-L-mannose). This is unusual, since most o ...

, and ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally-occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this compo ...

. In ''E. coli'', glucose catabolite repression is regulated by the phosphotransferase system PEP group translocation, also known as the phosphotransferase system or PTS, is a distinct method used by bacteria for sugar uptake where the source of energy is from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP). It is known to be a multicomponent system that always i ...

, a multi-protein phosphorylation

In chemistry, phosphorylation is the attachment of a phosphate group to a molecule or an ion. This process and its inverse, dephosphorylation, are common in biology and could be driven by natural selection. Text was copied from this source, wh ...

cascade that couples glucose uptake

Method of glucose uptake differs throughout tissues depending on two factors; the metabolic needs of the tissue and availability of glucose. The two ways in which glucose uptake can take place are facilitated diffusion (a passive process) and seco ...

and metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

.

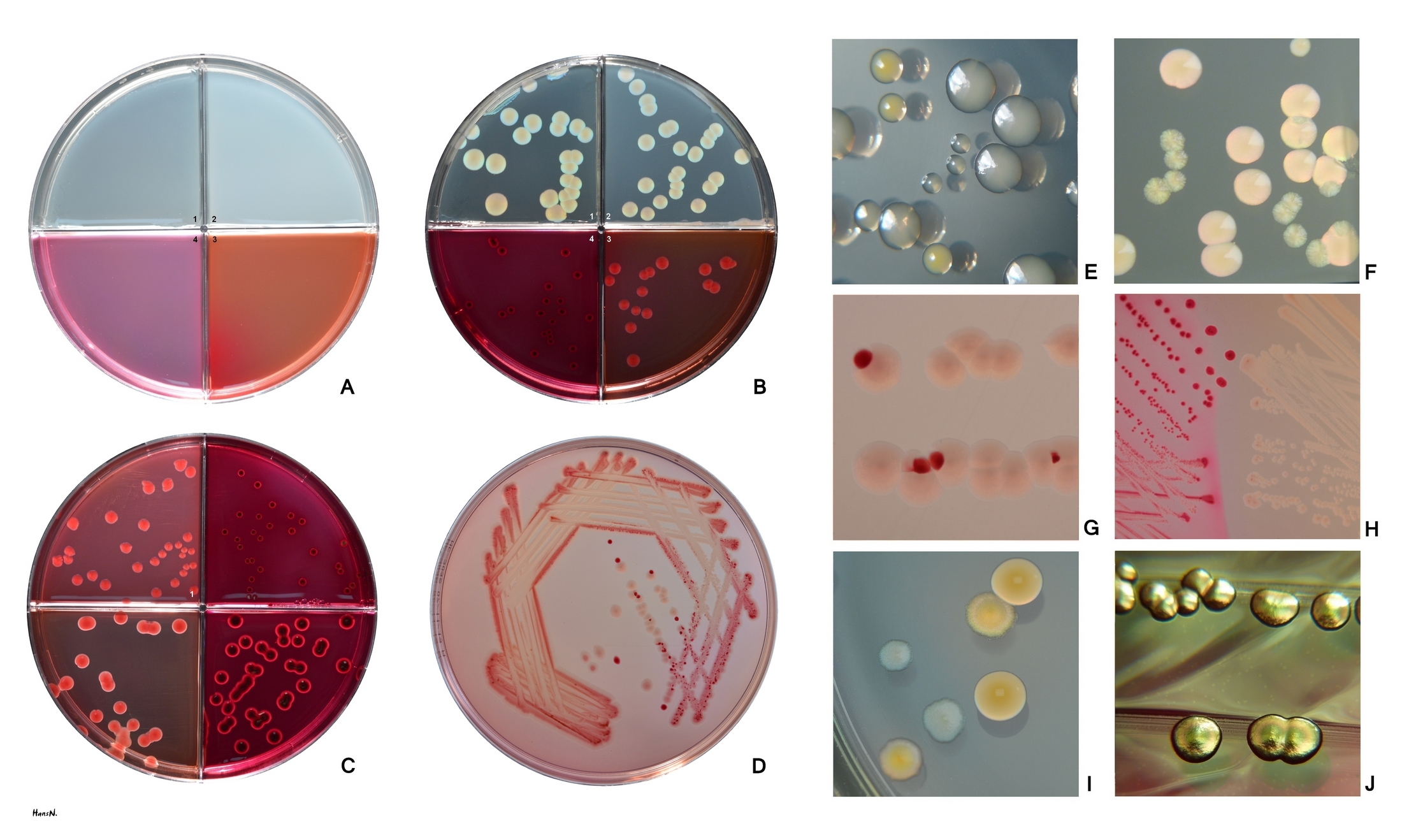

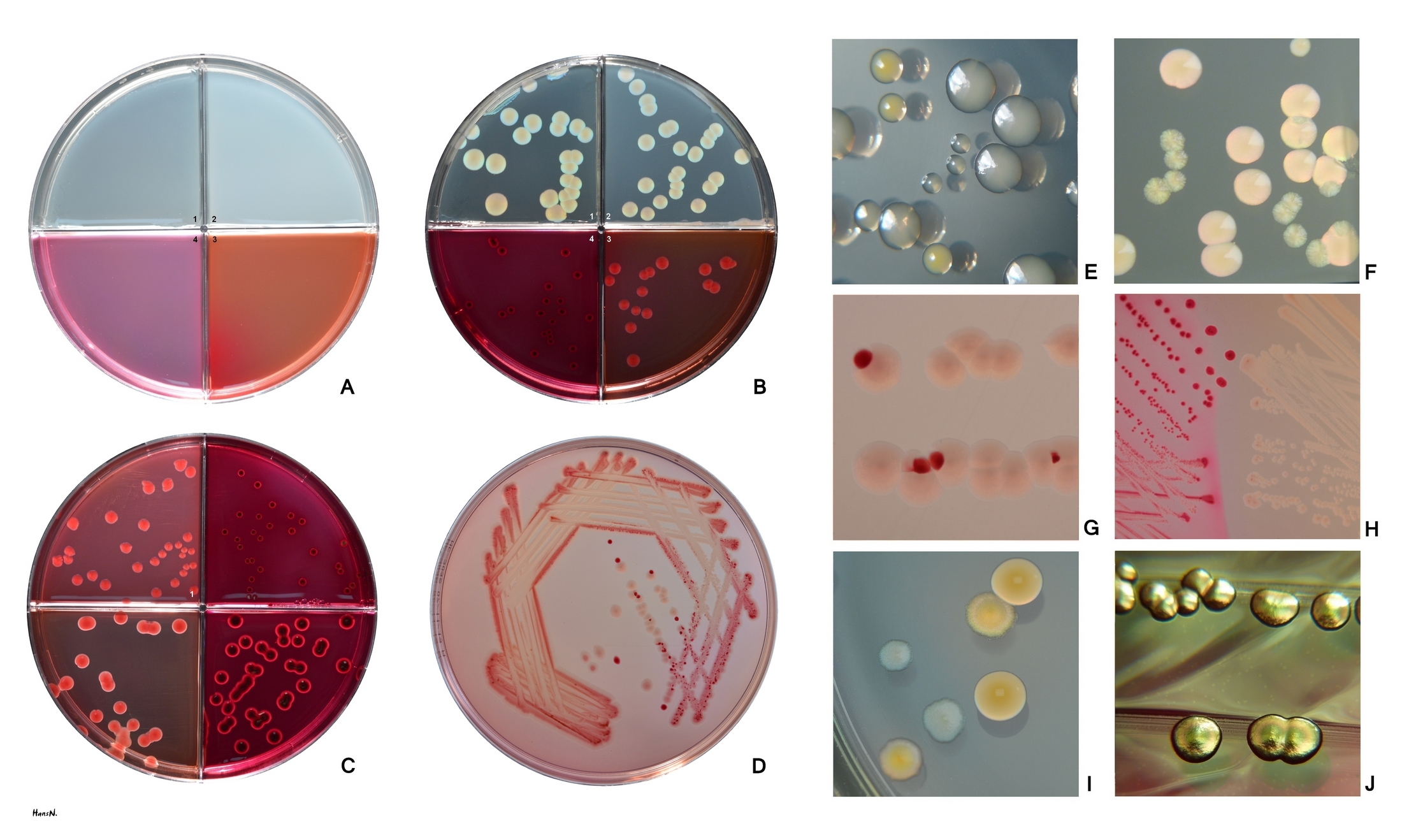

Culture growth

Optimum growth of ''E. coli'' occurs at , but some laboratory strains can multiply at temperatures up to . ''E. coli'' grows in a variety of defined laboratory media, such aslysogeny broth

Lysogeny broth (LB) is a nutritionally rich medium primarily used for the growth of bacteria. Its creator, Giuseppe Bertani, intended LB to stand for lysogeny broth, but LB has also come to colloquially mean Luria broth, Lennox broth, life broth ...

, or any medium that contains glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

, ammonium phosphate monobasic, sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as salt (although sea salt also contains other chemical salts), is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. With molar masses of 22.99 and 35.45 g ...

, magnesium sulfate

Magnesium sulfate or magnesium sulphate (in English-speaking countries other than the US) is a chemical compound, a salt with the formula , consisting of magnesium cations (20.19% by mass) and sulfate anions . It is a white crystalline solid, ...

, potassium phosphate dibasic, and water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

. Growth can be driven by aerobic

Aerobic means "requiring air," in which "air" usually means oxygen.

Aerobic may also refer to

* Aerobic exercise, prolonged exercise of moderate intensity

* Aerobics, a form of aerobic exercise

* Aerobic respiration, the aerobic process of cellu ...

or anaerobic respiration

Anaerobic respiration is respiration using electron acceptors other than molecular oxygen (O2). Although oxygen is not the final electron acceptor, the process still uses a respiratory electron transport chain.

In aerobic organisms undergoing re ...

, using a large variety of redox pairs, including the oxidation of pyruvic acid

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic aci ...

, formic acid

Formic acid (), systematically named methanoic acid, is the simplest carboxylic acid, and has the chemical formula HCOOH and structure . It is an important intermediate in chemical synthesis and occurs naturally, most notably in some ants. Es ...

, hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

, and amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s, and the reduction of substrates such as oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

, nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion

A polyatomic ion, also known as a molecular ion, is a covalent bonded set of two or more atoms, or of a metal complex, that can be considered to behave as a single unit and that has a net charge that is not zer ...

, fumarate

Fumaric acid is an organic compound with the formula HO2CCH=CHCO2H. A white solid, fumaric acid occurs widely in nature. It has a fruit-like taste and has been used as a food additive. Its E number is E297.

The salts and esters are known as f ...

, dimethyl sulfoxide

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is an organosulfur compound with the formula ( CH3)2. This colorless liquid is the sulfoxide most widely used commercially. It is an important polar aprotic solvent that dissolves both polar and nonpolar compounds a ...

, and trimethylamine N-oxide

Trimethylamine ''N''-oxide (TMAO) is an organic compound with the formula (CH3)3NO. It is in the class of amine oxides. Although the anhydrous compound is known, trimethylamine ''N''-oxide is usually encountered as the dihydrate. Both the anhydro ...

. ''E. coli'' is classified as a facultative anaerobe

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

. It uses oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

when it is present and available. It can, however, continue to grow in the absence of oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

using fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food ...

or anaerobic respiration

Anaerobic respiration is respiration using electron acceptors other than molecular oxygen (O2). Although oxygen is not the final electron acceptor, the process still uses a respiratory electron transport chain.

In aerobic organisms undergoing re ...

. Respiration type is managed in part by the arc system

The Arc system is a two-component system found in some bacteria that regulates gene expression in faculatative anaerobes such as ''Escheria coli''. Two-component system means that it has a sensor molecule and a response regulator. Arc is an abb ...

. The ability to continue growing in the absence of oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

is an advantage to bacteria because their survival is increased in environments where water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

predominates.

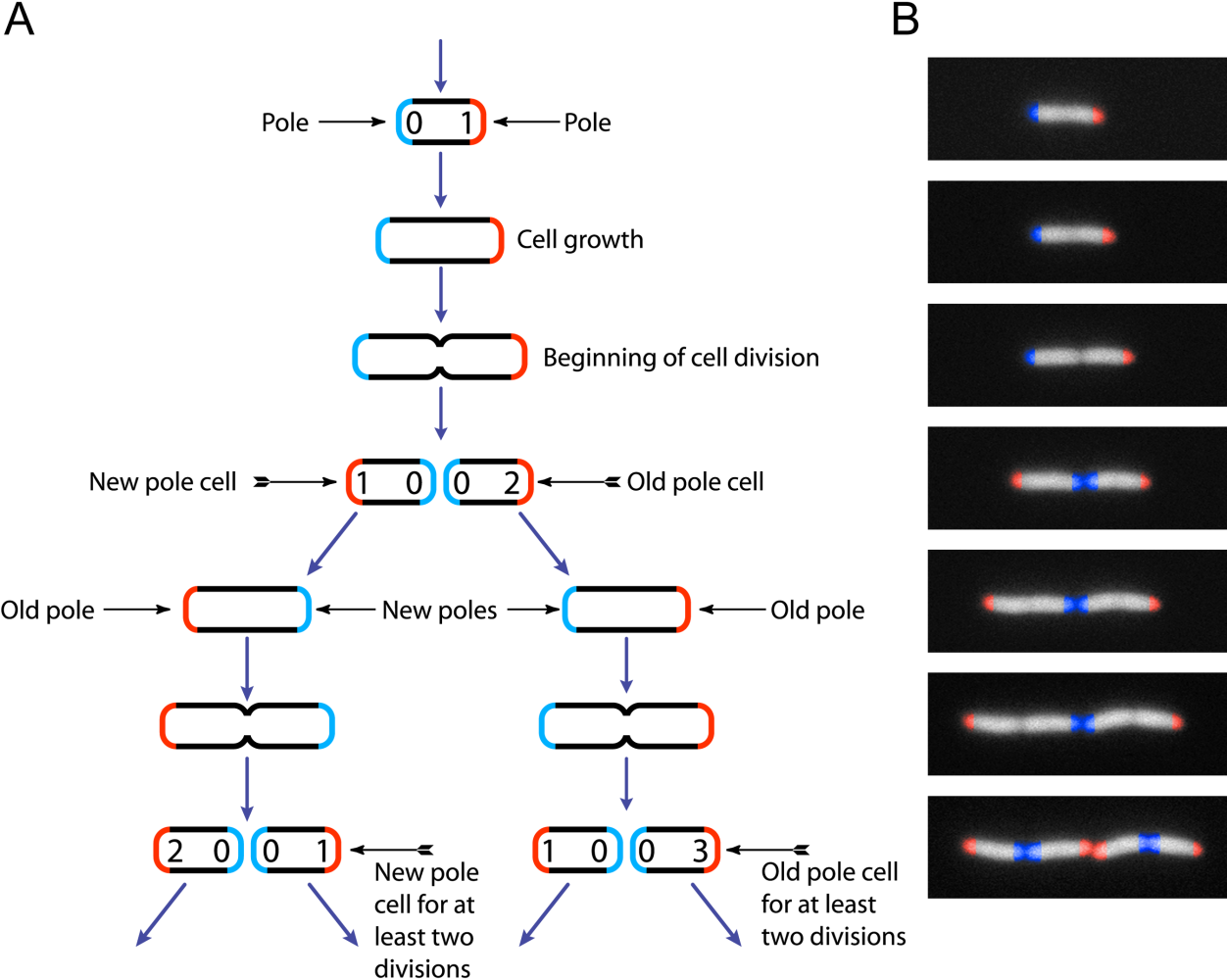

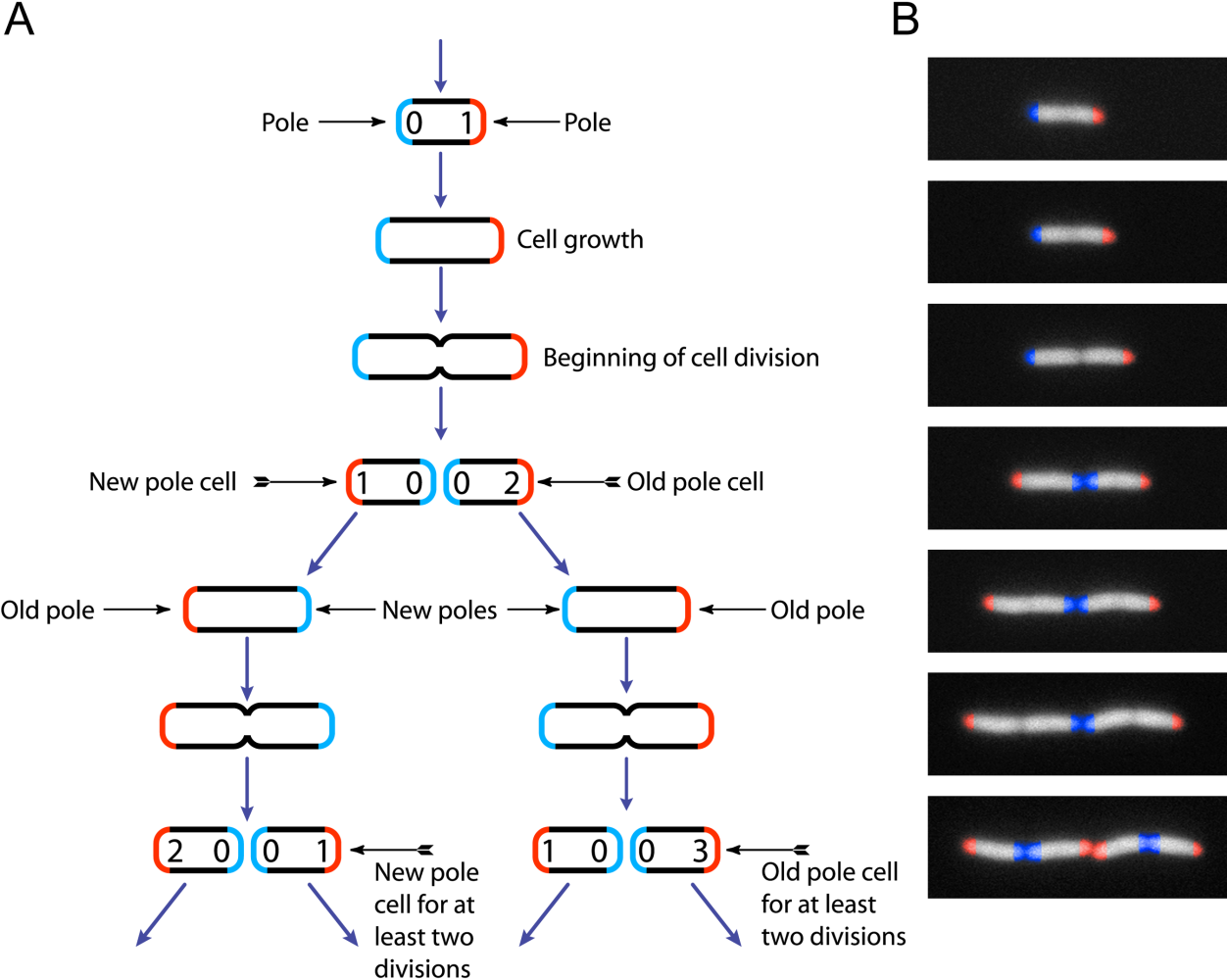

Cell cycle

The bacterial cell cycle is divided into three stages. The B period occurs between the completion of cell division and the beginning ofDNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

. The C period encompasses the time it takes to replicate the chromosomal DNA. The D period refers to the stage between the conclusion of DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

and the end of cell division. The doubling rate of ''E. coli'' is higher when more nutrients are available. However, the length of the C and D periods do not change, even when the doubling time becomes less than the sum of the C and D periods. At the fastest growth rates, replication begins before the previous round of replication has completed, resulting in multiple replication forks along the DNA and overlapping cell cycles.

The number of replication forks in fast growing ''E. coli'' typically follows 2n (n = 1, 2 or 3). This only happens if replication is initiated simultaneously from all origins of replications, and is referred to as synchronous replication. However, not all cells in a culture replicate synchronously. In this case cells do not have multiples of two replication fork

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

s. Replication initiation is then referred to being asynchronous. However, asynchrony can be caused by mutations to for instance DnaA

Introduction

Based on the Replicon Model, a positively active initiator molecule contacts with a particular spot on a circular chromosome called the replicator to start DNA replication. DnaA is a protein that activates initiation of DNA replica ...

or DnaA

Introduction

Based on the Replicon Model, a positively active initiator molecule contacts with a particular spot on a circular chromosome called the replicator to start DNA replication. DnaA is a protein that activates initiation of DNA replica ...

initiator-associating protein DiaA Diaa ( ar, ضياء) is an Egyptian male given name.

Notable people with this name include:

* Ahmed Diaa Eddine (1912–1976), Egyptian film director

* Diaa al-Din Dawoud (1926–2011), Egyptian politician

* Diaa Raofat (born 1988), Egyptian footba ...

.

Although ''E. coli'' reproduces by binary fission

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two digits (0 and 1)

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical operation that t ...

the two supposedly identical cells produced by cell division are functionally asymmetric with the old pole cell acting as an aging parent that repeatedly produces rejuvenated offspring. When exposed to an elevated stress level, damage accumulation in an old ''E. coli'' lineage may surpass its immortality threshold so that it arrests division and becomes mortal. Cellular aging

Programmed cell death (PCD; sometimes referred to as cellular suicide) is the death of a cell (biology), cell as a result of events inside of a cell, such as apoptosis or autophagy. PCD is carried out in a biological process, which usually confers ...

is a general process, affecting prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s and eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s alike.

Genetic adaptation

''E. coli'' and related bacteria possess the ability to transfer DNA viabacterial conjugation

Bacterial conjugation is the transfer of genetic material between bacterial cells by direct cell-to-cell contact or by a bridge-like connection between two cells. This takes place through a pilus. It is a parasexual mode of reproduction in bacteri ...

or transduction, which allows genetic material to spread horizontally through an existing population. The process of transduction, which uses the bacterial virus called a bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

, is where the spread of the gene encoding for the Shiga toxin

Shiga toxins are a family of related toxins with two major groups, Stx1 and Stx2, expressed by genes considered to be part of the genome of lambdoid prophages. The toxins are named after Kiyoshi Shiga, who first described the bacterial orig ...

from the ''Shigella

''Shigella'' is a genus of bacteria that is Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, non-spore-forming, nonmotile, rod-shaped, and genetically closely related to ''E. coli''. The genus is named after Kiyoshi Shiga, who first discovered it in 1897. ...

'' bacteria to ''E. coli'' helped produce ''E. coli'' O157:H7, the Shiga toxin-producing strain of ''E. coli.''

Diversity

''E. coli'' encompasses an enormous population of bacteria that exhibit a very high degree of both genetic and phenotypic diversity. Genome sequencing of many isolates of ''E. coli'' and related bacteria shows that a taxonomic reclassification would be desirable. However, this has not been done, largely due to its medical importance, and ''E. coli'' remains one of the most diverse bacterial species: only 20% of the genes in a typical ''E. coli'' genome is shared among all strains. In fact, from the more constructive point of view, the members of genus ''Shigella'' (''S. dysenteriae'', ''S. flexneri'', ''S. boydii'', and ''S. sonnei'') should be classified as ''E. coli'' strains, a phenomenon termedtaxa in disguise

In bacteriology, a taxon in disguise is a species, genus or higher unit of biological classification whose evolutionary history reveals has evolved from another unit of a similar or lower rank, making the parent unit paraphyletic. That happens whe ...

. Similarly, other strains of ''E. coli'' (e.g. the K-12

K-1 is a professional kickboxing promotion established in 1993, well known worldwide mainly for its heavyweight division fights and Grand Prix tournaments. In January 2012, K-1 Global Holdings Limited, a company registered in Hong Kong, acquired ...

strain commonly used in recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be foun ...

work) are sufficiently different that they would merit reclassification.

A strain

Strain may refer to:

Science and technology

* Strain (biology), variants of plants, viruses or bacteria; or an inbred animal used for experimental purposes

* Strain (chemistry), a chemical stress of a molecule

* Strain (injury), an injury to a mu ...

is a subgroup

In group theory, a branch of mathematics, given a group ''G'' under a binary operation ∗, a subset ''H'' of ''G'' is called a subgroup of ''G'' if ''H'' also forms a group under the operation ∗. More precisely, ''H'' is a subgroup ...

within the species that has unique characteristics that distinguish it from other strains. These differences are often detectable only at the molecular level; however, they may result in changes to the physiology or lifecycle of the bacterium. For example, a strain may gain pathogenic capacity, the ability to use a unique carbon source

The molecules that an organism uses as its carbon source for generating biomass are referred to as "carbon sources" in biology. It's possible for a organic or inorganic sources of carbon. Heterotrophs must use organic molecules as both a source of ...

, the ability to take upon a particular ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

, or the ability to resist antimicrobial agents

An antimicrobial is an agent that kills microorganisms or stops their growth. Antimicrobial medicines can be grouped according to the microorganisms they act primarily against. For example, antibiotics are used against bacteria, and antifungals ar ...

. Different strains of ''E. coli'' are often host-specific, making it possible to determine the source of fecal contamination in environmental samples. For example, knowing which ''E. coli'' strains are present in a water sample allows researchers to make assumptions about whether the contamination originated from a human, another mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

, or a bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

.

Serotypes

A common subdivision system of ''E. coli'', but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface

A common subdivision system of ''E. coli'', but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

s (O antigen: part of lipopolysaccharide

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are large molecules consisting of a lipid and a polysaccharide that are bacterial toxins. They are composed of an O-antigen, an outer core, and an inner core all joined by a covalent bond, and are found in the outer m ...

layer; H: flagellin

Flagellin is a globular protein that arranges itself in a hollow cylinder to form the filament in a bacterial flagellum. It has a mass of about 30,000 to 60,000 daltons. Flagellin is the principal component of bacterial flagella, and is present ...

; K antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

: capsule), e.g. O157:H7). It is, however, common to cite only the serogroup, i.e. the O-antigen. At present, about 190 serogroups are known. The common laboratory strain has a mutation that prevents the formation of an O-antigen and is thus not typeable.

Genome plasticity and evolution

Like all lifeforms, new strains of ''E. coli'' evolve through the natural biological processes of

Like all lifeforms, new strains of ''E. coli'' evolve through the natural biological processes of mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

, gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene. ...

, and horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

; in particular, 18% of the genome of the laboratory strain MG1655 was horizontally acquired since the divergence from ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of rod-shaped (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' is the type species and is fur ...

''. ''E. coli'' K-12 and ''E. coli'' B strains are the most frequently used varieties for laboratory purposes. Some strains develop traits that can be harmful to a host animal. These virulent

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ca ...

strains typically cause a bout of diarrhea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin wi ...

that is often self-limiting in healthy adults but is frequently lethal to children in the developing world. More virulent strains, such as O157:H7, cause serious illness or death in the elderly, the very young, or the immunocompromised

Immunodeficiency, also known as immunocompromisation, is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious diseases and cancer is compromised or entirely absent. Most cases are acquired ("secondary") due to extrinsic factors that a ...

.

The genera ''Escherichia

''Escherichia'' () is a genus of Gram-negative, non- spore-forming, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria from the family Enterobacteriaceae. In those species which are inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tracts of warm-blooded animals, ...

'' and ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of rod-shaped (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' is the type species and is fur ...

'' diverged around 102 million years ago (credibility interval: 57–176 mya), an event unrelated to the much earlier (see ''Synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

'') divergence of their hosts: the former being found in mammals and the latter in birds and reptiles. This was followed by a split of an ''Escherichia'' ancestor into five species ('' E. albertii'', ''E. coli'', '' E. fergusonii'', '' E. hermannii'', and '' E. vulneris''). The last ''E. coli'' ancestor split between 20 and 30 million years ago.

The long-term evolution experiments using ''E. coli'', begun by Richard Lenski

Richard Eimer Lenski (born August 13, 1956) is an American evolutionary biologist, a Hannah Distinguished Professor of Microbial Ecology at Michigan State University. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and a MacArthur fellow. ...

in 1988, have allowed direct observation of genome evolution over more than 65,000 generations in the laboratory. For instance, ''E. coli'' typically do not have the ability to grow aerobically with citrate

Citric acid is an organic compound with the chemical formula HOC(CO2H)(CH2CO2H)2. It is a colorless weak organic acid. It occurs naturally in citrus fruits. In biochemistry, it is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle, which occurs in t ...

as a carbon source

The molecules that an organism uses as its carbon source for generating biomass are referred to as "carbon sources" in biology. It's possible for a organic or inorganic sources of carbon. Heterotrophs must use organic molecules as both a source of ...

, which is used as a diagnostic criterion with which to differentiate ''E. coli'' from other, closely, related bacteria such as ''Salmonella''. In this experiment, one population of ''E. coli'' unexpectedly evolved the ability to aerobically metabolize citrate

Citric acid is an organic compound with the chemical formula HOC(CO2H)(CH2CO2H)2. It is a colorless weak organic acid. It occurs naturally in citrus fruits. In biochemistry, it is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle, which occurs in t ...

, a major evolutionary shift with some hallmarks of microbial speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

. In the microbial world, a relationship of predation can be established similar to that observed in the animal world. Considered, it has been seen that ''E. coli'' is the prey of multiple generalist predators, such as ''

In the microbial world, a relationship of predation can be established similar to that observed in the animal world. Considered, it has been seen that ''E. coli'' is the prey of multiple generalist predators, such as ''Myxococcus xanthus

''Myxococcus xanthus'' is a gram-negative, rod-shaped species of myxobacteria that exhibits various forms of self-organizing behavior in response to environmental cues. Under normal conditions with abundant food, it exists as a predatory, saproph ...

''. In this predator-prey relationship, a parallel evolution of both species is observed through genomic and phenotypic modifications, in the case of ''E. coli'' the modifications are modified in two aspects involved in their virulence such as mucoid production (excessive production of exoplasmic acid alginate ) and the suppression of the OmpT

OmpT is an aspartyl protease found on the outer membrane of ''Escherichia coli''. OmpT is a subtype of the family of omptin proteases, which are found on some gram-negative species of bacteria.

Structure

OmpT is a 33.5 kDa outer membrane protei ...

gene, producing in future generations a better adaptation of one of the species that is counteracted by the evolution of the other, following a co-evolutionary model demonstrated by the Red Queen hypothesis

The Red Queen hypothesis is a hypothesis in evolutionary biology proposed in 1973, that species must constantly adapt, evolve, and proliferate in order to survive while pitted against ever-evolving opposing species. The hypothesis was intended t ...

.

Neotype strain

''E. coli'' is the type species of the genus (''Escherichia'') and in turn ''Escherichia'' is the type genus of the familyEnterobacteriaceae

Enterobacteriaceae is a large family (biology), family of Gram-negative bacteria. It was first proposed by Rahn in 1936, and now includes over 30 genera and more than 100 species. Its classification above the level of family is still a subject ...

, where the family name does not stem from the genus ''Enterobacter

''Enterobacter'' is a genus of common Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped, non-spore-forming bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. It is the type genus of the order Enterobacterales. Several strains of these bacteria are pat ...

'' + "i" (sic.) + " aceae", but from "enterobacterium" + "aceae" (enterobacterium being not a genus, but an alternative trivial name to enteric bacterium).

The original strain described by Escherich is believed to be lost, consequently a new type strain (neotype) was chosen as a representative: the neotype strain is U5/41T, also known under the deposit names DSM 30083, ATCC 11775, and NCTC 9001, which is pathogenic to chickens and has an O1:K1:H7 serotype

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or cells are classified together based on their surface antigens, allowing the epi ...

. However, in most studies, either O157:H7, K-12 MG1655, or K-12 W3110 were used as a representative ''E. coli''. The genome of the type strain has only lately been sequenced.

Phylogeny of ''E. coli'' strains

Many strains belonging to this species have been isolated and characterised. In addition to serotype (''vide supra''), they can be classified according to theirphylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

, i.e. the inferred evolutionary history, as shown below where the species is divided into six groups as of 2014. Particularly the use of whole genome sequences yields highly supported phylogenies. The phylogroup

{{Short pages monitor