eremitic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A hermit, also known as an eremite ( adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in

A hermit, also known as an eremite ( adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in

In the common Christian tradition the first known Christian hermit in Egypt was Paul of Thebes (

In the common Christian tradition the first known Christian hermit in Egypt was Paul of Thebes (

In the

In the

From a religious point of view, the solitary life is a form of

From a religious point of view, the solitary life is a form of

*

*

* In medieval

* In medieval

Rotha Mary Clay, Full Text + Illustrations, The Hermits and Anchorites of England.

The tradition of the Lersi Hermits

Resources and reflections on hermits and solitude

{{Authority control Asceticism Religious occupations Types of saints

A hermit, also known as an eremite ( adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in

A hermit, also known as an eremite ( adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion

Seclusion is the act of secluding (i.e. isolating from society), the state of being secluded, or a place that facilitates it (a secluded place). A person, couple, or larger group may go to a secluded place for privacy or peace and quiet. The se ...

. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

InChristianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

, the term was originally applied to a Christian who lives the eremitic life out of a religious conviction, namely the Desert Theology of the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

(i.e., the 40 years wandering in the desert that was meant to bring about a change of heart).

In the Christian tradition the eremitic life is an early form of monastic living

''Monastic Living'' is an EP by the American indie rock band Parquet Courts, released on November 27, 2015, on Rough Trade Records. The release features mostly improvised instrumental and experimental recordings.

Background and recording

Compari ...

that preceded the monastic life in the cenobium. In chapter 1, the Rule of St Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's R ...

lists hermits among four kinds of monks. In the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, in addition to hermits who are members of religious institute

A religious institute is a type of institute of consecrated life in the Catholic Church whose members take religious vows and lead a life in community with fellow members. Religious institutes are one of the two types of institutes of consecra ...

s, the Canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

(canon 603) recognizes also diocesan hermits under the direction of their bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

as members of the consecrated life. The same is true in many parts of the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and oth ...

, including the Episcopal Church in the United States, although in the canon law of the Episcopal Church they are referred to as "solitaries" rather than "hermits".

Often, both in religious and secular literature, the term "hermit" is used loosely for any Christian living a secluded prayer-focused life, and sometimes interchangeably with anchorite/anchoress, recluse

A recluse is a person who lives in voluntary seclusion from the public and society. The word is from the Latin ''recludere'', which means "shut up" or "sequester". Historically, the word referred to a Christian hermit's total isolation from t ...

and "solitary". Other religions, including Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or ''dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global po ...

, Islam (Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

), and Taoism

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the '' Ta ...

, afford examples of hermits in the form of adherents living an ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

way of life.

In modern colloquial usage, "hermit" denotes anyone living apart from the rest of society, or having entirely or in part withdrawn from society, for any reason.

Etymology

The word ''hermit'' comes from theLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

''ĕrēmīta'', the latinisation of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

ἐρημίτης (''erēmitēs''), "of the desert", which in turn comes from ἔρημος (''erēmos''), signifying "desert", "uninhabited", hence "desert-dweller"; adjective: "eremitic".

History

Tradition

In the common Christian tradition the first known Christian hermit in Egypt was Paul of Thebes (

In the common Christian tradition the first known Christian hermit in Egypt was Paul of Thebes (fl.

''Floruit'' (; abbreviated fl. or occasionally flor.; from Latin for "they flourished") denotes a date or period during which a person was known to have been alive or active. In English, the unabbreviated word may also be used as a noun indicatin ...

3rd century), hence also called "St. Paul the first hermit". Antony of Egypt (fl. 4th century), often referred to as "Antony the Great", is perhaps the most renowned of all the early Christian hermits owing to the biography by Athanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

. An antecedent for Egyptian eremiticism may have been the Syrian solitary or "son of the covenant" (Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

''bar qəyāmā'') who undertook special disciplines as a Christian.

Christian hermits in the past have often lived in isolated cells or hermitages, whether a natural cave or a constructed dwelling, situated in the desert or the forest. People sometimes sought them out for spiritual advice and counsel. Some eventually acquired so many disciples

A disciple is a follower and student of a mentor, teacher, or other figure. It can refer to:

Religion

* Disciple (Christianity), a student of Jesus Christ

* Twelve Apostles of Jesus, sometimes called the Twelve Disciples

* Seventy disciples in ...

that they no longer enjoyed physical solitude. Some early Christian Desert Fathers wove baskets to exchange for bread.

In medieval times hermits were also found within or near cities where they might earn a living as a gate keeper or ferryman. In the 10th century, a rule for hermits living in a monastic community was written by Grimlaicus Grimlaicus or Grimlaic was a cleric who lived in ninth- or tenth-century Francia, probably around Metz.

He is known only for the book he wrote on how to lead a solitary life within a monastic community, the ''Regula Solitariorum''. This was the firs ...

. In the 11th century, the life of the hermit gained recognition as a legitimate independent pathway to salvation. Many hermits in that century and the next came to be regarded as saints. From the Middle Ages and down to modern times, eremitic monasticism has also been practiced within the context of religious institutes in the Christian West.

In the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

the Carthusians

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has i ...

and Camaldolese

The Camaldolese Hermits of Mount Corona ( la, Congregatio Eremitarum Camaldulensium Montis Coronae), commonly called Camaldolese is a monastic order of Pontifical Right for men founded by Saint Romuald. Their name is derived from the Holy Hermit ...

arrange their monasteries as clusters of hermitages where the monks live most of their day and most of their lives in solitary prayer and work, gathering only briefly for communal prayer and only occasionally for community meals and recreation. The Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Sain ...

, Trappist

The Trappists, officially known as the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance ( la, Ordo Cisterciensis Strictioris Observantiae, abbreviated as OCSO) and originally named the Order of Reformed Cistercians of Our Lady of La Trappe, are a ...

and Carmelite

, image =

, caption = Coat of arms of the Carmelites

, abbreviation = OCarm

, formation = Late 12th century

, founder = Early hermits of Mount Carmel

, founding_location = Mount Car ...

orders, which are essentially communal in nature, allow members who feel a calling to the eremitic life, after years living in the cenobium or community of the monastery, to move to a cell suitable as a hermitage on monastery grounds. There have also been many hermits who chose that vocation as an alternative to other forms of monastic life.

Anchorites

The term "anchorite" (from theGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''anachōreō'', signifying "to withdraw", "to depart into the country outside the circumvallate city") is often used as a synonym for hermit, not only in the earliest written sources but throughout the centuries. Yet the anchoritic life, while similar to the eremitic life, can also be distinct from it. Anchorites lived the religious life in the solitude of an "anchorhold" (or "anchorage"), usually a small hut or "cell", typically built against a church. The door of an anchorage tended to be bricked up in a special ceremony conducted by the local bishop after the anchorite had moved in. Medieval churches survive that have a tiny window ("squint") built into the shared wall near the sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred place, such as a shrine. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This secondary use can be categorized into human sanctuary, a s ...

to allow the anchorite to participate in the liturgy by listening to the service and to receive Holy Communion

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in others. According to the New Testame ...

. Another window looked out into the street or cemetery, enabling charitable neighbors to deliver food and other necessities. Clients seeking the anchorite's advice might also use this window to consult them.

Contemporary Christian life

Catholicism

Catholics who wish to live in eremitic monasticism may live thatvocation

A vocation () is an occupation to which a person is especially drawn or for which they are suited, trained or qualified. People can be given information about a new occupation through student orientation. Though now often used in non-religious ...

as a hermit:

* in an eremitic order, for example Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has ...

or Camaldolese

The Camaldolese Hermits of Mount Corona ( la, Congregatio Eremitarum Camaldulensium Montis Coronae), commonly called Camaldolese is a monastic order of Pontifical Right for men founded by Saint Romuald. Their name is derived from the Holy Hermit ...

(in the latter one affiliate oblate

In Christianity (especially in the Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican and Methodist traditions), an oblate is a person who is specifically dedicated to God or to God's service.

Oblates are individuals, either laypersons or clergy, normally li ...

s may also live as hermits)

* as a diocesan hermit under the canonical direction of their bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

(canon 603, see below)

There are also lay people who informally follow an eremitic lifestyle and live mostly as solitaries. Not all the Catholic lay members that feel that it is their vocation to dedicate themselves to God in a prayerful solitary life perceive it as a vocation to some form of consecrated life. An example of this is life as a Poustinik

A hermitage most authentically refers to a place where a hermit lives in seclusion from the world, or a building or settlement where a person or a group of people lived religiously, in seclusion. Particularly as a name or part of the name of pro ...

, an Eastern Catholic expression of eremitic living that is finding adherents also in the West.

Eremitic members of religious institutes

In the

In the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the institutes of consecrated life have their own regulations concerning those of their members who feel called by God to move from the life in community to the eremitic life, and have the permission of their religious superior to do so. The Code of Canon Law contains no special provisions for them. They technically remain a member of their institute of consecrated life

An institute of consecrated life is an association of faithful in the Catholic Church erected by canon law whose members profess the evangelical counsels of chastity, poverty, and obedience by vows or other sacred bonds. They are defined in the ...

and thus under obedience to their religious superior.

The Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has ...

and Camaldolese

The Camaldolese Hermits of Mount Corona ( la, Congregatio Eremitarum Camaldulensium Montis Coronae), commonly called Camaldolese is a monastic order of Pontifical Right for men founded by Saint Romuald. Their name is derived from the Holy Hermit ...

orders of monks and nuns preserve their original way of life as essentially eremitic within a cenobitical context, that is, the monasteries of these orders are in fact clusters of individual hermitages where monks and nuns spend their days alone with relatively short periods of prayer in common.

Other orders that are essentially cenobitical, notably the Trappists

The Trappists, officially known as the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance ( la, Ordo Cisterciensis Strictioris Observantiae, abbreviated as OCSO) and originally named the Order of Reformed Cistercians of Our Lady of La Trappe, are a ...

, maintain a tradition under which individual monks or nuns who have reached a certain level of maturity within the community may pursue a hermit lifestyle on monastery grounds under the supervision of the abbot or abbess. Thomas Merton

Thomas Merton (January 31, 1915 – December 10, 1968) was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist and scholar of comparative religion. On May 26, 1949, he was ordained to the Catholic priesthood and g ...

was among the Trappists who undertook this way of life.

Diocesan hermits

The earliest form of Christian eremitic or anchoritic living preceded that as a member of a religious institute, since monastic communities and religious institutes are later developments of the monastic life. Bearing in mind that the meaning of the eremitic vocation is the Desert Theology of the Old Testament, it may be said that the desert of the urban hermit is that of their heart, purged throughkenosis

In Christian theology, ''kenosis'' () is the 'self-emptying' of Jesus. The word () is used in Philippians 2:7: " made himself nothing" ( NIV), or " eemptied himself" (NRSV), using the verb form (), meaning "to empty".

The exact meaning var ...

to be the dwelling place of God alone.

So as to provide for men and women who feel a vocation

A vocation () is an occupation to which a person is especially drawn or for which they are suited, trained or qualified. People can be given information about a new occupation through student orientation. Though now often used in non-religious ...

to the eremitic or anchoritic life without being or becoming a member of an institute of consecrated life, but desire its recognition by the Roman Catholic Church as a form of consecrated life nonetheless, the 1983 Code of Canon Law legislates in the Section on Consecrated Life (canon 603) as follows:

Canon 603 §2 lays down the requirements for diocesan hermits.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church

The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' ( la, Catechismus Catholicae Ecclesiae; commonly called the ''Catechism'' or the ''CCC'') is a catechism promulgated for the Catholic Church by Pope John Paul II in 1992. It aims to summarize, in book ...

of 11 October 1992 (§§918–921) comments on the eremitic life as follows:

Catholic Church norms for the consecrated eremitic and anchoritic life do not include corporal works of mercy. Nevertheless, every hermit, like every Christian, is bound by the law of charity and therefore ought to respond generously, as his or her own circumstances permit, when faced with a specific need for corporal works of mercy. Hermits are also bound by the law of work. If they are not financially independent, they may engage in cottage industries or be employed part-time in jobs that respect the call for them to live in solitude and silence with extremely limited or no contact with other persons. Such outside jobs may not keep them from observing their obligations of the eremitic vocation of stricter separation from the world and the silence of solitude in accordance with canon 603, under which they have made their vow. Although canon 603 makes no provision for associations of hermits, these do exist (for example the Hermits of Bethlehem in Chester NJ and the Hermits of Saint Bruno in the United States; see also lavra

A lavra or laura ( el, Λαύρα; Cyrillic: Ла́вра) is a type of monastery consisting of a cluster of cells or caves for hermits, with a church and sometimes a refectory at the center. It is erected within the Orthodox and other Easte ...

, skete

A skete ( ) is a monastic community in Eastern Christianity that allows relative isolation for monks, but also allows for communal services and the safety of shared resources and protection. It is one of four types of early monastic orders, al ...

).

Anglicanism

Many of the recognised religious communities and orders in theAnglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and oth ...

make provision for certain members to live as hermits, more commonly referred to as solitaries. One Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

community, the Society of St. John the Evangelist

The Society of St John the Evangelist (SSJE) is an Anglican religious order for men. The members live under a rule of life and, at profession, make monastic vows of poverty, celibacy and obedience.

SSJE was founded in 1866 at Cowley, Oxford, Eng ...

, now has only solitaries in its British congregation. Anglicanism also makes provision for men and women who seek to live a single consecrated life, after taking vows before their local bishop; many who do so live as solitaries. The ''Handbook of Religious Life'', published by the Advisory Council of Relations between Bishops and Religious Communities, contains an appendix governing the selection, consecration, and management of solitaries living outside recognised religious communities.

In the Canon Law of the Episcopal Church (United States)

The Episcopal Church, based in the United States with additional dioceses elsewhere, is a member church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. It is a mainline Protestant denomination and is divided into nine provinces. The presiding bishop o ...

, those who make application to their diocesan bishop and who persevere in whatever preparatory program the bishop requires, take vows that include lifelong celibacy. They are referred to as solitaries rather than hermits. Each selects a bishop other than their diocesan as an additional spiritual resource and, if necessary, an intermediary. At the start of the twenty-first century the Church of England reported a notable increase in the number of applications from people seeking to live the single consecrated life as Anglican hermits or solitaries. A religious community known as the Solitaries of DeKoven, who make Anglican prayer beads and Pater Noster cord

The Pater Noster cord (also spelled Paternoster Cord and called Paternoster beads) is a set of prayer beads used in Christianity to recite the 150 Psalms, as well as the Lord's Prayer. As such, Paternoster cords traditionally consist of 150 bead ...

s to support themselves, are an example of an Anglican hermitage.

Eastern Orthodoxy

In the Orthodox Church andEastern Rite Catholic Church

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of th ...

es, hermits live a life of prayer as well as service to their community in the traditional Eastern Christian manner of the poustinik. The poustinik is a hermit available to all in need and at all times. In the Eastern Christian churches one traditional variation of the Christian eremitic life is the semi-eremitic life in a lavra

A lavra or laura ( el, Λαύρα; Cyrillic: Ла́вра) is a type of monastery consisting of a cluster of cells or caves for hermits, with a church and sometimes a refectory at the center. It is erected within the Orthodox and other Easte ...

or skete

A skete ( ) is a monastic community in Eastern Christianity that allows relative isolation for monks, but also allows for communal services and the safety of shared resources and protection. It is one of four types of early monastic orders, al ...

, exemplified historically in Scetes, a place in the Egyptian desert, and continued in various sketes today including several regions on Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; el, Ἄθως, ) is a mountain in the distal part of the eponymous Athos peninsula and site of an important centre of Eastern Orthodox monasticism in northeastern Greece. The mountain along with the respective part of the peni ...

.

Notable Christian hermits

Early and Medieval Church

* Paul of Thebes, 4th century, Egypt, regarded by St. Jerome as the first hermit * Abba Or of Nitria, 4th century, Egypt. * Anthony of Egypt, 4th century, Egypt, a Desert Father, regarded as the founder of Christian Monasticism * Macarius of Egypt, 4th century, founder of theMonastery of Saint Macarius the Great

The Monastery of Saint Macarius The Great also known as Dayr Aba Maqār ( ar, دير الأنبا مقار) is a Coptic Orthodox monastery located in Wadi El Natrun, Beheira Governorate, about north-west of Cairo, and off the highway betwee ...

, presumed author of "Spiritual Homilies"

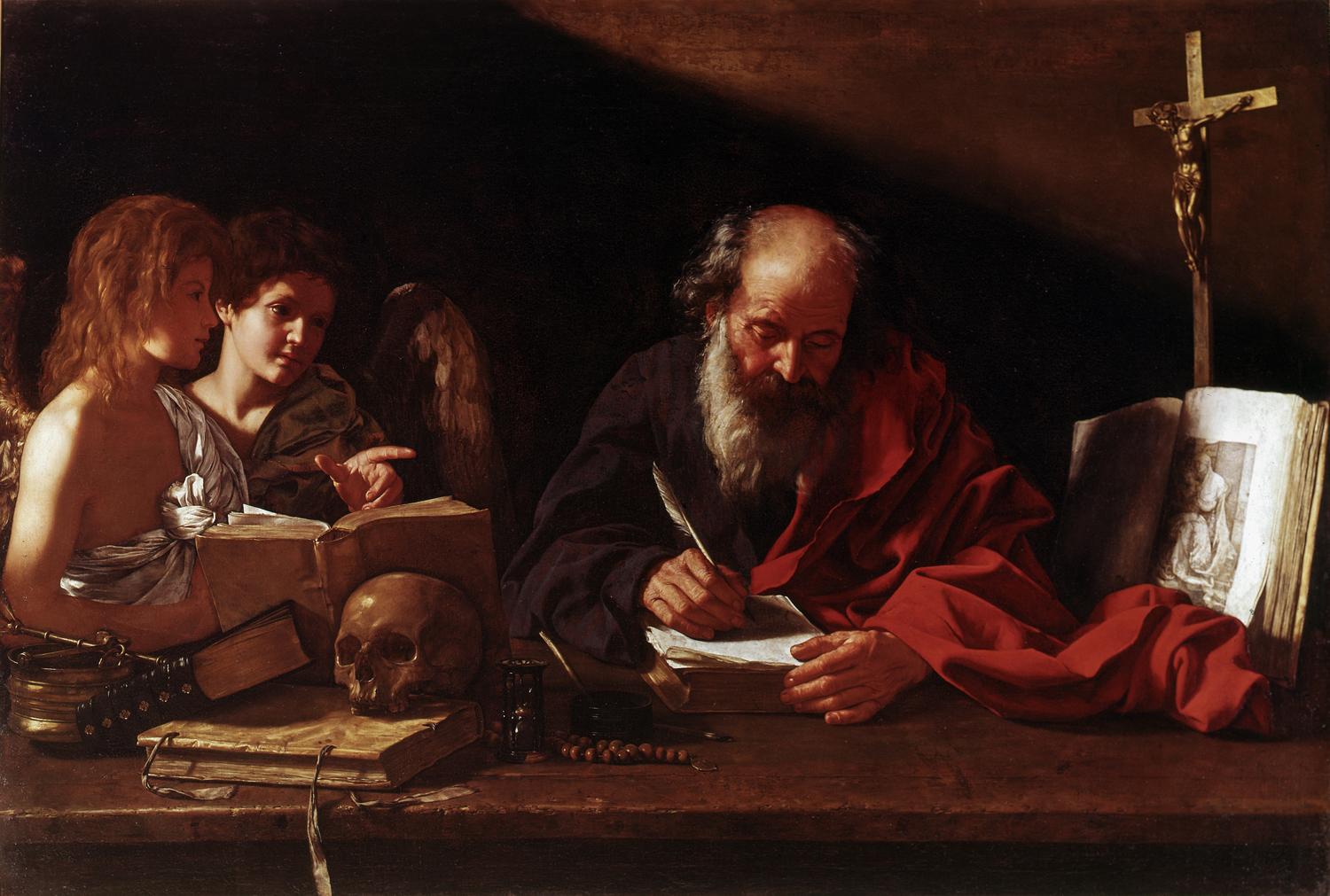

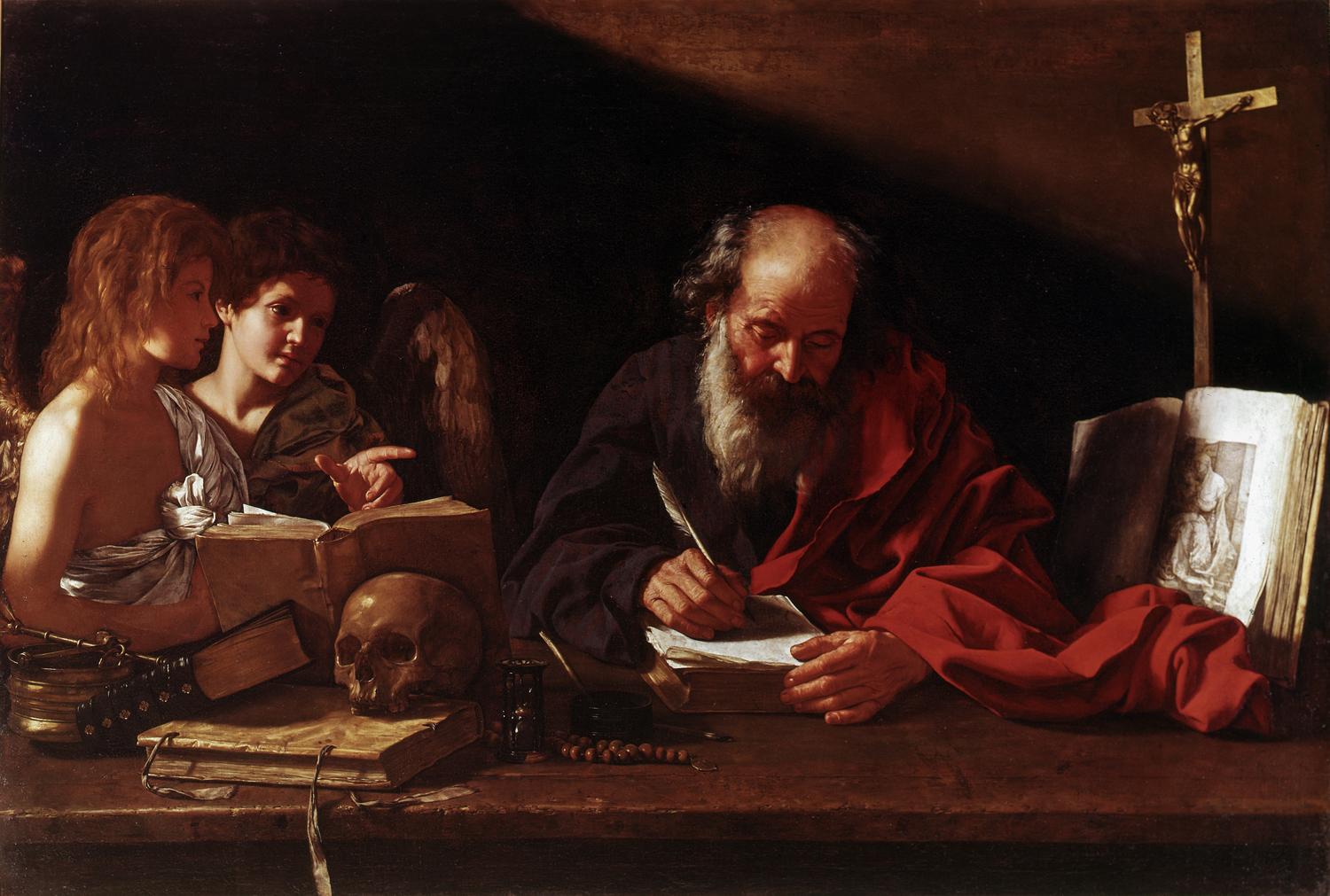

* St. Jerome, 4th century, Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

region, Doctor of the Church

Doctor of the Church (Latin: ''doctor'' "teacher"), also referred to as Doctor of the Universal Church (Latin: ''Doctor Ecclesiae Universalis''), is a title given by the Catholic Church to saints recognized as having made a significant contribu ...

, considered the spiritual father of the Hieronymite eremitic order

* Syncletica of Alexandria, 4th century, Egypt, one of the early Desert Mothers, her maxims are included in the sayings of the Desert Fathers

* Gregory the Illuminator

Gregory the Illuminator ( Classical hy, Գրիգոր Լուսաւորիչ, reformed: Գրիգոր Լուսավորիչ, ''Grigor Lusavorich'';, ''Gregorios Phoster'' or , ''Gregorios Photistes''; la, Gregorius Armeniae Illuminator, cu, Svyas ...

, 4th century, brought the Christian faith to Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ...

* Mary of Egypt, 4th/5th century, Egypt and Transjordan, penitent

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of Repentance (theology), repentance for Christian views on sin, sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic Church, Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox s ...

* Simeon Stylites

Simeon Stylites or Symeon the Stylite syc, ܫܡܥܘܢ ܕܐܣܛܘܢܐ ', Koine Greek ', ar, سمعان العمودي ' (c. 390 – 2 September 459) was a Syrian Christian ascetic, who achieved notability by living 37 years on a smal ...

, 4th/5th century, Syria, pillar saint

* Sarah of the Desert, 5th century, Egypt, one of the Desert Mothers, her maxims are recorded in the sayings of the Desert Fathers

* St Benedict of Nursia, 6th century, Italy, author of the so-called Rule of St Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's R ...

, regarded as the founder of western monasticism

* Kevin of Glendalough, 6th Century, Ireland

* St. Gall

Gall ( la, Gallus; 550 646) according to hagiographic tradition was a disciple and one of the traditional twelve companions of Columbanus on his mission from Ireland to the continent. Deicolus was the elder brother of Gall.

Biography

The ...

, 7th century, Switzerland, namesake of the city

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be de ...

and canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ent ...

of St. Gallen.

* Herbert of Derwentwater, 7th century, England.

* St. Romuald, 10th/11th century, Italy, founder of the Camaldolese

The Camaldolese Hermits of Mount Corona ( la, Congregatio Eremitarum Camaldulensium Montis Coronae), commonly called Camaldolese is a monastic order of Pontifical Right for men founded by Saint Romuald. Their name is derived from the Holy Hermit ...

order

* Guðríðr Þorbjarnardóttir, 10th/11th century, Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

.

* St. Bruno of Cologne

Bruno of Cologne, O.Cart. (german: Bruno von Köln, it, Bruno di Colonia;c. 1030 – 6 October 1101), venerated as Saint Bruno, was the founder of the Carthusian Order. He personally founded the order's first two communities. He was a celebrate ...

, 11th century, France, the founder of the Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has ...

order

* Peter the Hermit, 11th century, France, leader of the People's Crusade

* Blessed Eusebius of Esztergom, 13th century, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

, the founder of the Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit

* Bl. Gonçalo de Amarante

Gundisalvus of Amarante ( pt, Gonçalo de Amarante; 1187 - 10 January 1259) was a Portuguese Catholic priest and a professed member from the Order of Preachers. He became a Dominican friar and hermit after his return from a long pilgrimage that ...

, 13th century, Portugal, Dominican friar

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of Cal ...

* Richard Rolle de Hampole

Richard Rolle ( – 30 September 1349) was an English hermit, mystic, and religious writer. He is also known as Richard Rolle of Hampole or de Hampole, since at the end of his life he lived near a Cistercian nunnery in Hampole, now in Sout ...

, 13th century, England, religious writer

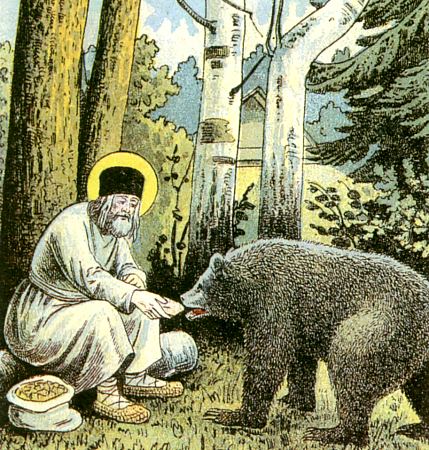

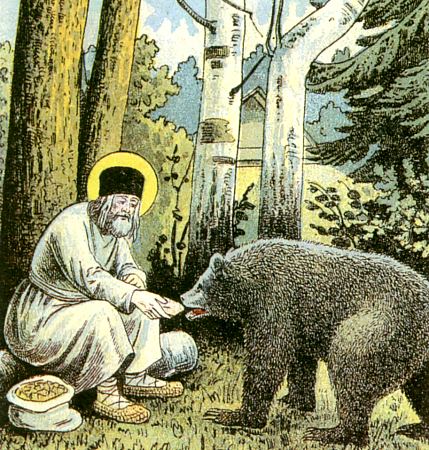

* Sergius of Radonezh

Sergius of Radonezh (russian: Се́ргий Ра́донежский, ''Sergii Radonezhsky''; 14 May 1314 – 25 September 1392), also known as Sergiy Radonezhsky, Serge of Radonezh and Sergius of Moscow, was a spiritual leader and monastic re ...

, 14th century

* Nicholas of Flüe

Nicholas of Flüe (german: Niklaus von Flüe; 1417 – 21 March 1487) was a Swiss hermit and ascetic who is the patron saint of Switzerland. He is sometimes invoked as Brother Klaus. A farmer, military leader, member of the assembly, councillo ...

, 15th century, patron saint of Switzerland

* Julian of Norwich

Julian of Norwich (1343 – after 1416), also known as Juliana of Norwich, Dame Julian or Mother Julian, was an English mystic and anchoress of the Middle Ages. Her writings, now known as ''Revelations of Divine Love'', are the earlies ...

, 15th century, England, anchoress

In Christianity, an anchorite or anchoret (female: anchoress) is someone who, for religious reasons, withdraws from secular society so as to be able to lead an intensely prayer-oriented, ascetic, or Eucharist-focused life. While anchorites are ...

* St. Juan Diego

Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, also known as Juan Diego (; 1474–1548), was a Chichimec peasant and Marian visionary. He is said to have been granted apparitions of the Virgin Mary on four occasions in December 1531: three at the hill of Tepeyac an ...

, 1474–1548, Mexico, visionary of the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe

Our Lady of Guadalupe ( es, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe ( es, Virgen de Guadalupe), is a Catholic title of Mary, mother of Jesus associated with a series of five Marian apparitions, which are believed t ...

Modern times

Members of religious orders: *Thomas Merton

Thomas Merton (January 31, 1915 – December 10, 1968) was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist and scholar of comparative religion. On May 26, 1949, he was ordained to the Catholic priesthood and g ...

, 20th-century Trappist monk, spiritual writer

* Herman of Alaska

Herman of Alaska ( rus, Преподобный Ге́рман Аляскинский, r=Prepodobny German Alaskinsky; 1756 – November 15, 1837) was a Russian Orthodox monk and missionary to Alaska, which was then part of Russian America. His g ...

, 18th century

* Seraphim of Sarov, 18th/19th century

Diocesan hermits according to canon 603:

* Sr Scholastica Egan, writer on the eremitic vocation

* Sr Laurel M O'Neal, Er Dio, spiritual director, writer on eremitic life

* Hermits of Bethlehem, Chester, NJ (modern lavra)

Others:

* Japan's Naked Hermit lived on the island of Sotobanari

is one of the Yaeyama Islands, within the Sakishima Islands, at the southern end of the Ryukyu Islands. It is to the west of Iriomote Island, its nearest large neighbour. It is administered as part of the town of Taketomi, Okinawa, Taketomi, Ok ...

until he got sick and was forced to leave the island.

* Jeanne Le Ber, 17th/18th-century Canadian Catholic recluse, inspired the founding of the Order of female religious the Recluse Sisters / ''Les Recluses Missionaires''.

* Sister Wendy Beckett

Wendy Mary Beckett (25 February 1930 – 26 December 2018), better known as Sister Wendy, was a British religious sister and art historian who became known internationally during the 1990s when she presented a series of BBC television document ...

, formerly of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur

The Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur (Congregationis Sororum a Domina Nostra Namurcensi) are a Catholic institute of religious sisters, founded to provide education to the poor.

The institute was founded in Amiens, France, in 1804, but the oppos ...

, was also a consecrated virgin

In the Catholic Church, a consecrated virgin is a woman who has been consecrated by the church to a life of perpetual virginity as a bride of Christ. Consecrated virgins are consecrated by the diocesan bishop according to the approved liturgical ...

, lived in "monastic solitude"; art historian

* Catherine de Hueck Doherty, poustinik

A hermitage most authentically refers to a place where a hermit lives in seclusion from the world, or a building or settlement where a person or a group of people lived religiously, in seclusion. Particularly as a name or part of the name of pro ...

, foundress of the Madonna House Apostolate

* Charles de Foucauld, 19th/20th century, formerly Trappist monk, inspired the founding of the Little Brothers of Jesus

The Little Brothers of Jesus (; ; abbreviated PFJ) is a male religious congregation within the Catholic Church of pontifical right inspired by Charles de Foucauld. Founded in 1933 in France, the congregation first established itself in French ...

* Jan Tyranowski, spiritual mentor to the young Karol Wojtyla, who would eventually become Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

* Order of Watchers, a contemporary French Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

eremitic fraternity.

Other religions

From a religious point of view, the solitary life is a form of

From a religious point of view, the solitary life is a form of asceticism

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

, wherein the hermit renounces worldly concerns and pleasures. This can be done for many reasons, including: to come closer to the deity or deities they worship or revere, to devote one's energies to self-liberation from saṃsāra

''Saṃsāra'' (Devanagari: संसार) is a Pali/Sanskrit word that means "world". It is also the concept of rebirth and "cyclicality of all life, matter, existence", a fundamental belief of most Indian religions. Popularly, it is the c ...

, etc. This practice appears also in ancient Śramaṇa traditions, Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

, Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or ''dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global po ...

, Kejawèn and Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

. Taoism

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the '' Ta ...

also has a long history of ascetic and eremitic figures. In the ascetic eremitic life, the hermit seeks solitude for meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

, contemplation

In a religious context, the practice of contemplation seeks a direct awareness of the divine which transcends the intellect, often in accordance with prayer or meditation.

Etymology

The word ''contemplation'' is derived from the Latin word ' ...

, prayer

Prayer is an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication. In the narrow sense, the term refers to an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deifi ...

, self-awareness and personal development on physical and mental levels; without the distractions of contact with human society, sex, or the need to maintain socially acceptable standards of cleanliness, dress or communication. The ascetic discipline can also include a simplified diet and/or manual labor as a means of support.

Notable hermits in other religions

*

* Laozi

Laozi (), also known by numerous other names, was a semilegendary ancient Chinese Taoist philosopher. Laozi ( zh, ) is a Chinese honorific, generally translated as "the Old Master". Traditional accounts say he was born as in the state of ...

, the author of renowned Tao Te Ching

The ''Tao Te Ching'' (, ; ) is a Chinese classic text written around 400 BC and traditionally credited to the sage Laozi, though the text's authorship, date of composition and date of compilation are debated. The oldest excavated portion d ...

and founder of philosophical Taoism, who is known by some traditions that he spent his final days as a hermit.

* Zhang Daoling

Zhang Ling (; traditionally 34–156), courtesy name Fuhan (), was a Chinese religious leader who lived during the Eastern Han Dynasty credited with founding the Way of the Celestial Masters sect of Taoism, which is also known as the Way of the ...

, founder of Tianshi Dao

The Way of the Celestial Masters is a Chinese Daoist movement that was founded by Zhang Daoling in 142 AD. Its followers rebelled against the Han Dynasty, and won their independence in 194. At its height, the movement controlled a theocratic state ...

, retired and led a reclusive life at Mount Beimang, where he practiced Taoist methods to attain longevity.

* U Khandi, religious figure in Burma who lived as a hermit and meditated at the Mandalay Thakho hill and Shwe-myin-tin hill.

* Ajahn Mun Bhuridatta Thera

(หลวงปู่มั่น)Ajahn Mun ( th, อาจารย์มั่น)

, dharma_names = Bhuridatto

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Ban Khambong, Khong Chiam, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand

, death_date =

, death_place = Wat Pa Sutth ...

, who is credited for establishing the Thai Forest Tradition, spent his monastic life wandering through Thailand, Burma, and Laos, dwelling for the most part in the forest, engaged in the practice of meditation.

* Luang Pu Waen Suciṇṇo, highly respected monk of Thai Forest Tradition, who lived alone, practiced alone in forests and preferred seclusion.

* Nyanatiloka Mahathera, one of the earliest western Buddhist monks and founder of Island Hermitage.

* Ajahn Jayasāro, notable disciple of Ajahn Chah

Chah Subhaddo ( th, ชา สุภัทโท, known in English as Ajahn Chah, occasionally with honorific titles '' Luang Por'' and ''Phra'') also known by his honorific name "Phra Bodhiñāṇathera" ( th, พระโพธิญาณเ� ...

, living alone in Janamāra Hermitage.

* Yoshida Kenkō, Japanese author and Buddhist monk.

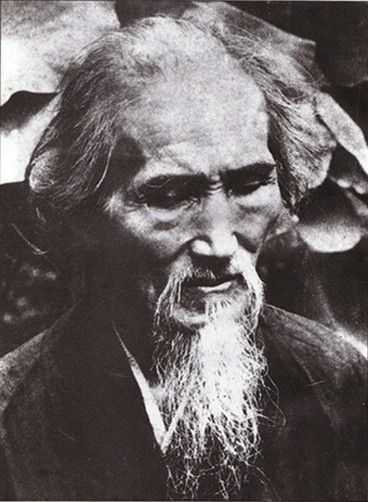

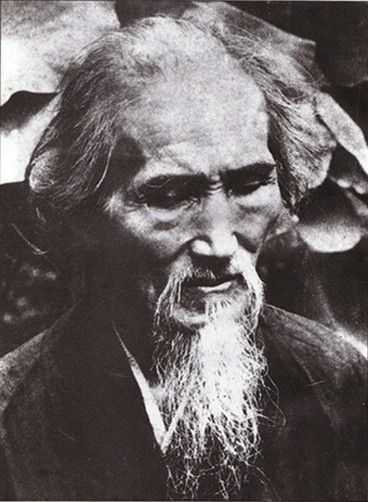

* Hsu Yun

Xuyun or Hsu Yun (; 5 September 1840? – 13 October 1959) was a renowned Chinese Chan Buddhist master and an influential Buddhist teacher of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Early life

Xuyun was purportedly born on 5 September 1840 in Fujian, Q ...

, renowned Ch'an Buddhist monk in modern China era.

* Hanshan, Buddhist/Taoist hermit and poet.

* Lin Bu

Lin Bu (; 967–1028) was a Chinese poet during the Northern Song dynasty. His courtesy name was Junfu (君復). One of the most famous verse masters of his time, Lin lived as a recluse by the West Lake in Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , ...

(林逋), a Song Dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

poet who spent much of his later life in solitude, while admiring plum blossoms, on a cottage by West Lake

West Lake (; ) is a freshwater lake in Hangzhou, China. It is divided into five sections by three causeways. There are numerous temples, pagodas, gardens, and natural/artificial islands within the lake. Gushan (孤山) is the largest natural ...

in Hangzhou.

* Ramana Maharshi

Ramana Maharshi (; 30 December 1879 – 14 April 1950) was an Indian Hindu sage and '' jivanmukta'' (liberated being). He was born Venkataraman Iyer, but is mostly known by the name Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi.

He was born in Tiruchuli, ...

, the renowned Hindu philosopher and saint who meditated for several years at and around the hillside temple of Thiruvannamalai in Southern India.

* The Baal Shem Tov

Israel ben Eliezer (1698 – 22 May 1760), known as the Baal Shem Tov ( he, בעל שם טוב, ) or as the Besht, was a Jewish mystic and healer who is regarded as the founder of Hasidic Judaism. "Besht" is the acronym for Baal Shem Tov, which ...

, founder of Hasidism

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism ( Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of cont ...

, lived for many years as a hermit in the Carpathian Mountains.

* Rabbi Nachman of Bratzlav, the Baal Shem Tov's great-grandson, also spent much time in seclusion and instructed his disciples to set aside at least one hour a day for secluded contemplation and prayer. Some followers of Rabbi Nachman devoted themselves to seclusion, such as Rabbi Shmuel of Dashev and two generations later, Rabbi Abraham Chazan.

* Rabbi Yosef Yozel Horowitz, known as the "Alter (Elder) of Novardok", succeeded his master Rabbi Yisrael Salanter in disseminating the pietistic teachings of the Lithuanian Mussar Movement. He too spent much time in seclusion, included one year during which he confined himself to a sealed room, attended by a few devoted followers.

* Ta Eisey

Ta Eisey also known as Lok Ta Maha Eisey is a foundational Khmer culture hero who is depicted as a hermit in Cambodia. It corresponds to the ''rishi'' of Vedic origin and represents the archetype of anachoretical life in Khmer culture. This h ...

, the archetype of the hermit in Khmer civilization

In literature

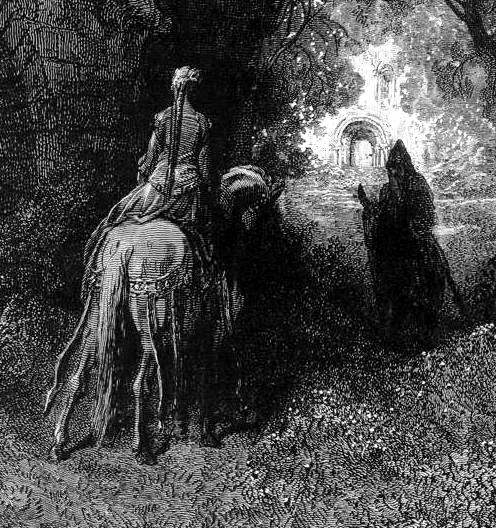

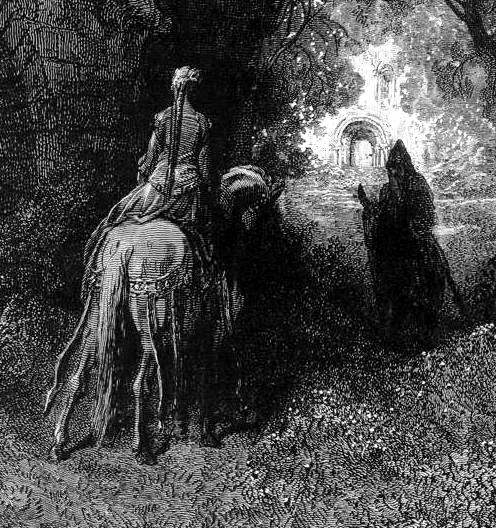

* In medieval

* In medieval romances

Romance (from Vulgar Latin , "in the Roman language", i.e., "Latin") may refer to:

Common meanings

* Romance (love), emotional attraction towards another person and the courtship behaviors undertaken to express the feelings

* Romance languages, ...

, the knight-errant frequently encounters hermits on his quest

A quest is a journey toward a specific mission or a goal. The word serves as a plot device in mythology and fiction: a difficult journey towards a goal, often symbolic or allegorical. Tales of quests figure prominently in the folklore of ev ...

. Such a figure, generally a wise old man, would advise him. Knights searching for the Holy Grail

The Holy Grail (french: Saint Graal, br, Graal Santel, cy, Greal Sanctaidd, kw, Gral) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miracu ...

, in particular, learn from a hermit the errors they must repent for, and the significance of their encounters, dreams, and visions. Evil wizards would sometimes pose as hermits, to explain their presence in the wilds, and to lure heroes into a false sense of security. In Edmund Spenser's ''The Faerie Queene

''The Faerie Queene'' is an English epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books IIII were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 together with books IVVI. ''The Faerie Queene'' is notable for its form: at over 36,000 lines and over 4,000 st ...

'', both occurred: the knight on a quest met a good hermit, and the sorcerer Archimago took on such a pose. These hermits are sometimes also vegetarians for ascetic reasons, as suggested in a passage from Sir Thomas Malory's '' Le Morte d'Arthur'': "Then departed Gawain and Ector as heavy (sad) as they might for their misadventure (mishap), and so rode till that they came to the rough mountain, and there they tied their horses and went on foot to the hermitage. And when they were (had) come up, they saw a poor house, and beside the chapel a little courtelage (courtyard), where Nacien the hermit gathered worts (vegetables), as he had tasted none other meat (food) of a great while." The practice of vegetarianism

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat ( red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetaria ...

may have also existed amongst actual medieval hermits outside of literature.

* Hermits appear in a few of the stories of Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was som ...

's ''The Decameron

''The Decameron'' (; it, label= Italian, Decameron or ''Decamerone'' ), subtitled ''Prince Galehaut'' (Old it, Prencipe Galeotto, links=no ) and sometimes nicknamed ''l'Umana commedia'' ("the Human comedy", as it was Boccaccio that dubbed Da ...

''. One of the most famous stories, the tenth story of the third day, involves the seduction of a young girl by a hermit in the desert near Gafsa

Gafsa ( aeb, ڨفصة '; ar, قفصة qafṣah), originally called Capsa in Latin, is the capital of Gafsa Governorate of Tunisia. It lends its Latin name to the Mesolithic Capsian culture. With a population of 111,170, Gafsa is the ninth- ...

; it was judged to be so obscene that it was not translated into English until the 20th century.

* The Three Hermits is a famous short story by Russian author Leo Tolstoy written in 1885 and first published in 1886, with its shock ending, featured the 3 hermits as the titular characters. The main character of Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

's short story " Father Sergius" is a Russian nobleman who turns to a solitary religious life and becomes a hermit after he learns that his fiancée was a discarded mistress of the czar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

.

* Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his c ...

, in his influential work ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra

''Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None'' (german: Also sprach Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen), also translated as ''Thus Spake Zarathustra'', is a work of philosophical fiction written by German philosopher Friedrich Niet ...

'', created the character of the hermit Zarathustra (named after the Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic ...

prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

Zarathushtra), who emerges from seclusion to extol his philosophy to the rest of humanity.

In media

* The 2021 BBC documentary ''The Hermit of Treig'' follows Ken Smith who has been a hermit for 40 yearsSee also

*Dhutanga

Dhutanga (Pali ''dhutaṅga,'' si, ධුතාඞ්ග) or dhūtaguṇa (Sanskrit) is a group of austerities or ascetic practices taught in Buddhism. The Theravada tradition teaches a set of thirteen dhutangas, while Mahayana Buddhist sources t ...

* Enclosed religious orders

Enclosed religious orders or ''cloistered clergy'' are religious orders whose members strictly separate themselves from the affairs of the external world. In the Catholic Church, enclosure is regulated by the code of canon law, either the Lat ...

* Garden hermit

Garden hermits or ornamental hermits were hermits (solitaries) encouraged to live in purpose-built hermitages, follies, grottoes, or rockeries on the estates of wealthy landowners, primarily during the 18th century. Such hermits would be encourag ...

* The Hermit (Tarot card)

* Sri Lankan Forest Tradition Sri Lankan Forest Monks' Tradition claims a long history. As the oldest Theravada Buddhist country in the world, several forest traditions and lineages had been existed, disappeared and re-emerged circularly in Sri Lanka. The current forest traditio ...

* Thai Forest Tradition

References

Citations

General and cited sources

* *External links

Rotha Mary Clay, Full Text + Illustrations, The Hermits and Anchorites of England.

The tradition of the Lersi Hermits

Resources and reflections on hermits and solitude

{{Authority control Asceticism Religious occupations Types of saints