equestrian (Roman) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The (; , though sometimes referred to as " knights" in English) constituted the second of the property/social-based classes of

Under Augustus, the senatorial elite was given formal status (as the ) with a higher wealth threshold (250,000 , or the pay of 1,100 legionaries) and superior rank and privileges to ordinary . During the Principate, filled the senior administrative and military posts of the imperial government. There was a clear division between jobs reserved for senators (the most senior) and those reserved for non-senatorial . But the career structure of both groups was broadly similar: a period of junior administrative posts in Rome or Roman Italy, followed by a period (normally a decade) of military service as a senior army officer, followed by senior administrative or military posts in the provinces. Senators and formed a tiny elite of under 10,000 members who monopolised political, military and economic power in an empire of about 60 million inhabitants.

During the 3rd century AD, power shifted from the Italian aristocracy to a class of who had earned their membership by distinguished military service, often rising from the ranks: career military officers from the provinces (especially the Balkan provinces) who displaced the Italian aristocrats in the top military posts, and under Diocletian (ruled 284–305) from the top civilian positions also. This effectively reduced the Italian aristocracy to an idle, but immensely wealthy, group of landowners. During the 4th century, the status of was debased to insignificance by excessive grants of the rank. At the same time the ranks of senators were swollen to over 4,000 by the establishment of the Byzantine Senate (a second senate in

Under Augustus, the senatorial elite was given formal status (as the ) with a higher wealth threshold (250,000 , or the pay of 1,100 legionaries) and superior rank and privileges to ordinary . During the Principate, filled the senior administrative and military posts of the imperial government. There was a clear division between jobs reserved for senators (the most senior) and those reserved for non-senatorial . But the career structure of both groups was broadly similar: a period of junior administrative posts in Rome or Roman Italy, followed by a period (normally a decade) of military service as a senior army officer, followed by senior administrative or military posts in the provinces. Senators and formed a tiny elite of under 10,000 members who monopolised political, military and economic power in an empire of about 60 million inhabitants.

During the 3rd century AD, power shifted from the Italian aristocracy to a class of who had earned their membership by distinguished military service, often rising from the ranks: career military officers from the provinces (especially the Balkan provinces) who displaced the Italian aristocrats in the top military posts, and under Diocletian (ruled 284–305) from the top civilian positions also. This effectively reduced the Italian aristocracy to an idle, but immensely wealthy, group of landowners. During the 4th century, the status of was debased to insignificance by excessive grants of the rank. At the same time the ranks of senators were swollen to over 4,000 by the establishment of the Byzantine Senate (a second senate in

ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian order was known as an ().

Description

During the Roman Kingdom and the first century of theRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

, legionary cavalry was recruited exclusively from the ranks of the patricians, who were expected to provide six (hundreds) of cavalry (300 horses for each consular legion). Around 400BC, 12 more of cavalry were established and these included non-patricians (plebeians

In ancient Rome, the plebeians or plebs were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not Patrician (ancient Rome), patricians, as determined by the Capite censi, census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Et ...

). Around 300 BC the Samnite Wars obliged Rome to double the normal annual military levy from two to four legions, doubling the cavalry levy from 600 to 1,200 horses. Legionary cavalry started to recruit wealthier citizens from outside the 18 . These new recruits came from the first class of commoners in the Centuriate Assembly organisation, and were not granted the same privileges.

By the time of the Second Punic War (218–202 BC), all the members of the first class of commoners were required to serve as cavalrymen. The presence of in the Roman cavalry diminished steadily in the period 200–88 BC as only could serve as the army's senior officers; as the number of legions proliferated fewer were available for ordinary cavalry service. After 88 BC, were no longer drafted into the legionary cavalry, although they remained technically liable to such service throughout the Principate era (to 284 AD). They continued to supply the senior officers of the army throughout the Principate.

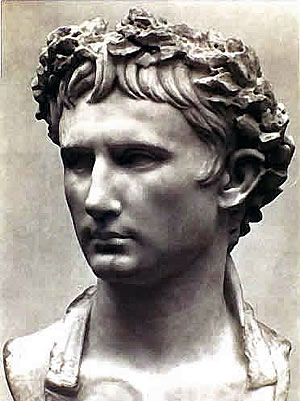

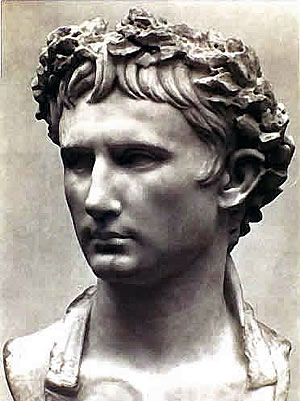

With the exception of the purely hereditary patricians, the were originally defined by a property threshold. The rank was passed from father to son, although members of the order who at the regular quinquennial (every five years) census no longer met the property requirement were usually removed from the order's rolls by the Roman censors. In the late republic, the property threshold stood at 50,000 and was doubled to 100,000 by the emperor Augustus (sole rule 30 BC – 14 AD) – roughly the equivalent to the annual salaries of 450 contemporary legionaries. In the later republican period, Roman senators and their offspring became an unofficial elite within the equestrian order.

Under Augustus, the senatorial elite was given formal status (as the ) with a higher wealth threshold (250,000 , or the pay of 1,100 legionaries) and superior rank and privileges to ordinary . During the Principate, filled the senior administrative and military posts of the imperial government. There was a clear division between jobs reserved for senators (the most senior) and those reserved for non-senatorial . But the career structure of both groups was broadly similar: a period of junior administrative posts in Rome or Roman Italy, followed by a period (normally a decade) of military service as a senior army officer, followed by senior administrative or military posts in the provinces. Senators and formed a tiny elite of under 10,000 members who monopolised political, military and economic power in an empire of about 60 million inhabitants.

During the 3rd century AD, power shifted from the Italian aristocracy to a class of who had earned their membership by distinguished military service, often rising from the ranks: career military officers from the provinces (especially the Balkan provinces) who displaced the Italian aristocrats in the top military posts, and under Diocletian (ruled 284–305) from the top civilian positions also. This effectively reduced the Italian aristocracy to an idle, but immensely wealthy, group of landowners. During the 4th century, the status of was debased to insignificance by excessive grants of the rank. At the same time the ranks of senators were swollen to over 4,000 by the establishment of the Byzantine Senate (a second senate in

Under Augustus, the senatorial elite was given formal status (as the ) with a higher wealth threshold (250,000 , or the pay of 1,100 legionaries) and superior rank and privileges to ordinary . During the Principate, filled the senior administrative and military posts of the imperial government. There was a clear division between jobs reserved for senators (the most senior) and those reserved for non-senatorial . But the career structure of both groups was broadly similar: a period of junior administrative posts in Rome or Roman Italy, followed by a period (normally a decade) of military service as a senior army officer, followed by senior administrative or military posts in the provinces. Senators and formed a tiny elite of under 10,000 members who monopolised political, military and economic power in an empire of about 60 million inhabitants.

During the 3rd century AD, power shifted from the Italian aristocracy to a class of who had earned their membership by distinguished military service, often rising from the ranks: career military officers from the provinces (especially the Balkan provinces) who displaced the Italian aristocrats in the top military posts, and under Diocletian (ruled 284–305) from the top civilian positions also. This effectively reduced the Italian aristocracy to an idle, but immensely wealthy, group of landowners. During the 4th century, the status of was debased to insignificance by excessive grants of the rank. At the same time the ranks of senators were swollen to over 4,000 by the establishment of the Byzantine Senate (a second senate in Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

) and the tripling of the membership of both senates. The senatorial order of the 4th century was thus the equivalent of the equestrian order of the Principate.

Regal era (753–509 BC)

According to Roman legend, Rome was founded by its first king, Romulus, in 753 BC. However, archaeological evidence suggests that Rome did not acquire the character of a unified city-state (as opposed to a number of separate hilltop settlements) until . Roman tradition relates that the Order of Knights was founded by Romulus, who supposedly established a cavalry regiment of 300 men called the ("Swift Squadron") to act as his personal escort, with each of the three Roman "tribes" (actually voting constituencies) supplying 100 horses. This cavalry regiment was supposedly doubled in size to 600 men by King Lucius Tarquinius Priscus (traditional dates 616–578 BC). That the cavalry was increased to 600 during the regal era is plausible, as in the early republic the cavalry fielded remained 600-strong (two legions with 300 horses each). However, according to Livy, King Servius Tullius (traditional reign-dates 578–535 BC) established a further 12 ''centuriae'' of ''equites'', a further tripling of the cavalry. Yet this was probably anachronistic, as it would have resulted in a contingent of 1,800 horse, incongruously large, compared to the heavy infantry, which was probably only 6,000 strong in the late regal period. Instead, the additional 12 ''centuriae'' were probably created at a later stage, perhaps around 400 BC, but these new units were political not military, most likely designed to admit plebeians to the Order of Knights. Apparently, ''equites'' were originally provided with a sum of money by the state to purchase a horse for military service and for its fodder. This was known as an ''equus publicus''. Theodor Mommsen argues that the royal cavalry was drawn exclusively from the ranks of the patricians (''patricii''), the aristocracy of early Rome, which was purely hereditary. Apart from the traditional association of the aristocracy with horsemanship, the evidence for this view is the fact that, during the republic, six ''centuriae'' (voting constituencies) of ''equites'' in the '' comitia centuriata'' (electoral assembly) retained the names of the original six royal cavalry ''centuriae''. These are very likely the "''centuriae'' of patrician nobles" in the ''comitia'' mentioned by the lexicologist Sextus Pompeius Festus. If this view is correct, it implies that the cavalry was exclusively patrician (and therefore hereditary) in the regal period. (However, Cornell considers the evidence tenuous).Early Republic (509–338 BC)

It is widely accepted that the Roman monarchy was overthrown by a patrician coup, probably provoked by the Tarquin dynasty's populist policies in favour of the plebeian class. The position and powers of a Roman king were thus similar to those ofJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

when he was appointed dictator-for-life in 44 BC. That was why Caesar's assassin, Marcus Junius Brutus, felt a moral obligation to emulate his claimed ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, "the Liberator", the man who, Roman tradition averred, in 509 BC, led the coup that overthrew the last king, Tarquin the Proud, and established the republic. Alfoldi suggests that the coup was carried out by the ''celeres'' themselves. According to the Fraccaro interpretation, when the Roman monarchy was replaced with two annually elected ''praetores'' (later called "consuls"), the royal army was divided equally between them for campaigning purposes, which, if true, explains why Polybius later said that a legion's cavalry contingent was 300 strong.

The 12 additional ''centuriae'' ascribed by Livy to Servius Tullius were, in reality, probably formed around 400 BC. In 403 BC, according to Livy, in a crisis during the siege of Veii, the army urgently needed to deploy more cavalry, and "those who possessed equestrian rating but had not yet been assigned public horses" volunteered to pay for their horses out of their own pockets. By way of compensation, pay was introduced for cavalry service, as it had already been for the infantry (in 406 BC).

The persons referred to in this passage were probably members of the 12 new ''centuriae'' who were entitled to public horses, but temporarily waived that privilege. Mommsen, however, argues that the passage refers to members of the first class of commoners being admitted to cavalry service in 403 BC for the first time as an emergency measure. If so, this group may be the original so-called ''equites'' ''equo privato'', a rank that is attested throughout the history of the republic (in contrast to ''equites'' ''equo publico''). However, due to a lack of evidence, the origins and definition of ''equo privato'' ''equites'' remain obscure.

It is widely agreed that the twelve new ''centuriae'' were open to non-patricians. Thus, from this date if not earlier, not all ''equites'' were patricians. The patricians, as a closed hereditary caste, steadily diminished in numbers over the centuries, as families died out. Around 450 BC, there are some 50 patrician '' gentes'' (clans) recorded, whereas just 14 remained at the time of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

(dictator of Rome 48–44 BC), whose own Iulii clan was patrician.

In contrast, the ranks of ''equites'', although also hereditary (in the male line), were open to new entrants who met the property requirement and who satisfied the Roman censors that they were suitable for membership. As a consequence, patricians rapidly became only a small minority of the equestrian order. However, patricians retained political influence greatly out of proportion with their numbers. Until 172 BC, one of the two consuls elected each year had to be a patrician.

In addition, patricians may have retained their original six ''centuriae'', which gave them a third of the total voting-power of the ''equites'', even though they constituted only a tiny minority of the order by 200 BC. Patricians also enjoyed official precedence, such as the right to speak first in senatorial debates, which were initiated by the ''princeps senatus'' (Leader of the Senate), a position reserved for patricians. In addition, patricians monopolized certain priesthoods and continued to enjoy enormous prestige.

Later Republic (338–30 BC)

Transformation of state and army (338–290)

The period following the end of the Latin War (340–338 BC) and of the Samnite Wars (343–290) saw the transformation of theRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

from a powerful but beleaguered city-state into the hegemonic power of the Italian peninsula. This was accompanied by profound changes in its constitution and army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

. Internally, the critical development was the emergence of the Senate as the all-powerful organ of state.

By 280 BC, the Senate had assumed total control of state taxation, expenditure, declarations of war, treaties, raising of legions, establishing colonies and religious affairs, in other words, of virtually all political power. From an ''ad hoc'' group of advisors appointed by the consuls, the Senate had become a permanent body of around 300 life peers who, as largely former Roman magistrates, boasted enormous experience and influence. At the same time, the political unification of the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

nation, under Roman rule after 338 BC, gave Rome a populous regional base from which to launch its wars of aggression against its neighbours.

The gruelling contest for Italian hegemony that Rome fought against the Samnite League led to the transformation of the Roman army from the Greek-style '' hoplite'' phalanx that it was in the early period, to the Italian-style manipular army described by Polybius. It is believed that the Romans copied the manipular structure from their enemies the Samnites, learning through hard experience its greater flexibility and effectiveness in the mountainous terrain of central Italy.

It is also from this period that every Roman army that took the field was regularly accompanied by at least as many troops supplied by the '' socii'' (Rome's Italian military confederates, often referred to as "Latin allies"). Each legion would be matched by a confederate ''ala'' (literally: "wing"), a formation that contained roughly the same number of infantry as a legion, but three times the number of horses (900).

Legionary cavalry also probably underwent a transformation during this period, from the light, unarmoured horsemen of the early period to the Greek-style armoured cuirassiers described by Polybius. As a result of the demands of the Samnite hostilities, a normal consular army was doubled in size to two legions, making four legions raised annually overall. Roman cavalry in the field thus increased to approximately 1,200 horses.

This now represented only 25% of the army's total cavalry contingent, the rest being supplied by the Italian confederates. A legion's modest cavalry share of 7% of its 4,500 total strength was thus increased to 12% in a confederate army, comparable with (or higher than) any other forces in Italy except the Gauls and also similar to those in Greek armies such as Pyrrhus's.

Political role

Despite an ostensibly democratic constitution based on the sovereignty of the people, the Roman Republic was in reality a classicoligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

, in which political power was monopolised by the richest social echelon. Probably by 300 BC, the ''centuriate'' organisation of the Roman citizen body for political purposes achieved the evolved form described by Polybius and Livy. The ''comitia centuriata'' was the most powerful people's assembly, as it promulgated Roman laws and annually elected the Roman magistrates, the executive officers of the state: consuls, '' praetors'', '' aediles'' and '' quaestors''.

In the assembly, the citizen body was divided into 193 ''centuriae'', or voting constituencies. Of these, 18 were allocated to ''equites'' (including patricians) and a further 80 to the first class of commoners, securing an absolute majority of the votes (98 out of 193) for the wealthiest echelon of society, although it constituted only a small minority of the citizenry. (The lowest class, the ''proletarii'', rated at under 400 ''drachmae'', had just one vote, despite being the most numerous).

As a result, the wealthiest echelon could ensure that the elected magistrates were always their own members. In turn, this ensured that the senate was dominated by the wealthy classes, as its membership was composed almost entirely of current and former magistrates.

Military officer role

In the Polybian army of the middle republic (338 – 88 BC), ''equites'' held the exclusive right to serve as senior officers of the army. These were the six ''tribuni militum'' in each legion who were elected by the ''comitia'' at the start of each campaigning season and took turns to command the legion in pairs; the ''praefecti sociorum'', commanders of the Italian confederate ''alae'', who were appointed by the consuls; and the three '' decurions'' that led each squadron ('' turma'') of legionary cavalry (a total of 30 ''decurions'' per legion).Cavalry role

As their name implies, ''equites'' were liable to cavalry service in the legion of the mid-republic. They originally provided a legion's entire cavalry contingent, although from an early stage (probably from c. 400 and not later than c. 300 BC), when equestrian numbers had become insufficient, large numbers of young men from the first class of commoners were regularly volunteering for the service, which was considered more glamorous than the infantry. The cavalry role of ''equites'' dwindled after the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), as the number of equestrians became insufficient to provide the senior officers of the army and general cavalrymen as well. ''Equites'' became exclusively an officer-class, with the first class of commoners providing the legionary cavalry.Ethos

From the earliest times and throughout the Republican period, Roman ''equites'' subscribed, in their role as Roman cavalrymen, to an ethos of personal heroism and glory. This was motivated by the desire to justify their privileged status to the lower classes that provided the infantry ranks, to enhance the renown of their family name, and to augment their chances of subsequent political advancement in a martial society. For ''equites'', a focus of the heroic ethos was the quest for '' spolia opima'', the stripped armour and weapons of a foe whom they had killed in single combat. There are many recorded instances. For example, Servilius Geminus Pulex, who went on to become Consul in 202 BC, was reputed to have gained ''spolia'' 23 times. The higher the rank of the opponent killed in combat, the more prestigious the ''spolia'', and none more so than ''spolia duci hostium detracta'', spoils taken from an enemy leader himself. Many ''equites'' attempted to gain such an honour, but very few succeeded for the reason that enemy leaders were always surrounded by large numbers of elite bodyguards. One successful attempt, but with a tragic twist, was that of the decurion Titus Manlius Torquatus in 340 BC during the Latin War. Despite strict orders from the consuls (one of whom was his own father) not to engage the enemy, Manlius could not resist accepting a personal challenge from the commander of the Tusculan cavalry, which his squadron encountered while on reconnaissance. There ensued a fiercely contested joust with the opposing squadrons as spectators. Manlius won, spearing his adversary after the latter was thrown by his horse. But when the triumphant young man presented the spoils to his father, the latter ordered his son's immediate execution for disobeying orders. "Orders of Manlius" (''Manliana imperia'') became a proverbial army term for orders that must on no account be disregarded.Business activities

In 218 BC, the '' lex Claudia'' restricted the commercial activity of senators and their sons, on the grounds that it was incompatible with their status. Senators were prohibited from owning ships of greater capacity than 300 amphorae (about seven tonnes) – this being judged sufficient to carry the produce of their own landed estates but too small to conduct large-scale sea transportation. From this time onwards, senatorial families mostly invested their capital in land. All other equestrians remained free to invest their wealth, greatly increased by the growth of Rome's overseas empire after the Second Punic War, in large-scale commercial enterprises including mining and industry, as well as land. Equestrians became especially prominent in tax farming and, by 100 BC, owned virtually all tax-farming companies ('' publicani''). During the late Republican era, the collection of most taxes was contracted out to private individuals or companies by competitive tender, with the contract for each province awarded to the ''publicanus'' who bid the highest advance to the state treasury on the estimated tax-take of the province. The ''publicanus'' would then attempt to recoup his advance, with the right to retain any surplus collected as his profit. This system frequently resulted in extortion from the common people of the provinces, as unscrupulous ''publicani'' often sought to maximise their profit by demanding a much higher rates of tax than originally set by the government. The provincial governors whose duty it was to curb illegal demands were often bribed into acquiescence by the ''publicani''. The system also led to political conflict between ''equites publicani'' and the majority of their fellow-''equites'', especially senators, who as large landowners wanted to minimise the tax on land outside Italy (''tributum solis''), which was the main source of state revenue. This system was terminated by the first Roman emperor, Augustus (sole rule 30 BC – 14 AD), who transferred responsibility for tax collection from the ''publicani'' to provincial local authorities (''civitates peregrinae''). Although the latter also frequently employed private companies to collect their tax quotas, it was in their own interests to curb extortion. During the imperial era, tax collectors were generally paid an agreed percentage of the amount collected. ''equites publicani'' became prominent in banking activities such as money-lending and money-changing.Privileges

The official dress of equestrians was the ''tunica angusticlavia'' (narrow-striped tunic), worn underneath the toga, in such a manner that the stripe over the right shoulder was visible (as opposed to the broad stripe worn by senators.) ''equites'' bore the title ''eques Romanus'', were entitled to wear an ''anulus aureus'' (gold ring) on their left hand, and, from 67 BC, enjoyed privileged seats at games and public functions (just behind those reserved for senators).Augustan equestrian order (Principate era)

Differentiation of the senatorial order

The Senate as a body was formed of sitting senators, whose number was held at around 600 by the founder of the Principate, Augustus (sole rule 30 BC – 14 AD) and his successors until 312. Senators' sons and further descendants technically retained equestrian rank unless and until they won a seat in the Senate. But Talbert argues that Augustus established the existing senatorial elite as a separate and superior order (''ordo senatorius'') to the ''equites'' for the first time. The evidence for this includes: * Augustus, for the first time, set a minimum property requirement for admission to the Senate, of 250,000 ''denarii'', two and a half times the 100,000 ''denarii'' that he set for admission to the equestrian order. * Augustus, for the first time, allowed the sons of senators to wear the ''tunica laticlavia'' (tunic with broad purple stripes that was the official dress of senators) on reaching their majority even though they were not yet members of the Senate. * Senators' sons followed a separate '' cursus honorum'' (career-path) to other ''equites'' before entering the Senate: first an appointment as one of the ''vigintiviri'' ("Committee of Twenty", a body that included officials with a variety of minor administrative functions), or as an ''augur'' (priest), followed by at least a year in the military as ''tribunus militum laticlavius'' (deputy commander) of a legion. This post was normally held before the tribune had become a member of the Senate. * A marriage law of 18 BC (the '' lex Julia'') seems to define not only senators but also their descendants unto the third generation (in the male line) as a distinct group. There was thus established a group of men with senatorial rank (''senatorii'') wider than just sitting senators (''senatores''). A family's senatorial status depended not only on continuing to match the higher wealth qualification, but on their leading member holding a seat in the Senate. Failing either condition, the family would revert to ordinary knightly status. Although sons of sitting senators frequently won seats in the Senate, this was by no means guaranteed, as candidates often outnumbered the 20 seats available each year, leading to intense competition.''Ordo equester'' under Augustus

As regards the equestrian order, Augustus apparently abolished the rank of ''equo privato'', according all its members ''equo publico'' status. In addition, Augustus organised the order in a quasi-military fashion, with members enrolled into six '' turmae'' (notional cavalry squadrons). The order's governing body were the ''seviri'' ("Committee of Six"), composed of the "commanders" of the ''turmae''. In an attempt to foster an ''esprit de corps'' amongst the ''equites'', Augustus revived a defunct republican ceremony, the ''recognitio equitum'' (inspection of the ''equites''), in which ''equites'' paraded every five years with their horses before the consuls. At some stage during the early Principate, ''equites'' acquired the right to the title "egregius" ("distinguished gentleman"), while senators were styled "''clarissimus''" ("most distinguished"). Beyond ''equites'' with ''equus publicus'', Augustus' legislation permitted any Roman citizen who was assessed in an official census as meeting the property requirement of 100,000 ''denarii'' to use the title of ''eques'' and wear the narrow-striped tunic and gold ring. But such "property-qualified ''equites''" were not apparently admitted to the ''ordo equester'' itself, but simply enjoyed equestrian status. Only those granted an ''equus publicus'' by the emperor (or who inherited the status from their fathers) were enrolled in the order. Imperial ''equites'' were thus divided into two tiers: a few thousand mainly Italian ''equites equo publico'', members of the order eligible to hold the public offices reserved for the ''equites''; and a much larger group of wealthy Italians and provincials (estimated at 25,000 in the 2nd century) of equestrian status but outside the order. Equestrians could in turn be elevated to senatorial rank (e.g., Pliny the Younger), but in practice this was much more difficult than elevation from commoner to equestrian rank. To join the upper order, not only was the candidate required to meet the minimum property requirement of 250,000 ''denarii'', but also had to be elected a member of the Senate. There were two routes for this, both controlled by the emperor: * The normal route was election to the post of '' quaestor'', the most junior magistracy (for which the minimum eligible age was 27 years), which carried automatic membership of the Senate. Twenty ''quaestors'' were appointed each year, a number that evidently broadly matched the average annual vacancies (caused by death or expulsion for misdemeanours or insufficient wealth) so that the 600-member limit was preserved. Under Augustus, senators' sons had the right to stand for election, while equestrians could only do so with the emperor's permission. Later in the Julio-Claudian period, the rule became established that all candidates required imperial leave. Previously conducted by the people's assembly (''comitia centuriata''), the election was in the hands, from the time of Tiberius onwards, of the Senate itself, whose sitting members inevitably favoured the sons of their colleagues. Since the latter alone often outnumbered the number of available places, equestrian candidates stood little chance unless they enjoyed the special support of the emperor. * The exceptional route was direct appointment to a Senate seat by the emperor ('' adlectio''), technically using the powers of Roman censor (which also entitled him to expel members). ''Adlectio'' was, however, generally used sparingly in order not to breach the 600-member ceiling. It was chiefly resorted to in periods when Senate numbers became severely depleted, e.g. during the Civil War of 68–69, following which the emperor Vespasian made large-scale ''adlectiones''.Equestrian public careers

Equestrians exclusively provided the ''praefecti'' (commanders) of the imperial army's auxiliary regiments and five of the six ''tribuni militum'' (senior staff officers) in each legion. The standard equestrian officer progression was known as the "'' tres militiae''" ("three services"): ''praefectus'' of a '' cohors'' (auxiliary infantry regiment), followed by ''tribunus militum'' in a legion, and finally ''praefectus'' of an '' ala'' (auxiliary cavalry regiment). From the time of Hadrian, a fourth militia was added for exceptionally gifted officers, commander of an ''ala milliaria'' (double-strength ''ala''). Each post was held for three to four years. Most of the top posts in the imperial administration were reserved for senators, who provided the governors of the larger provinces (except Egypt), the ''legati legionis'' (legion commanders) of all legions outside Egypt, and the '' praefectus urbi'' (prefect of the city of Rome), who controlled the '' cohortes urbanae'' (public order battalions), the only fully armed force in the city apart from the Praetorian Guard. Nevertheless, a wide range of senior administrative and military posts were created and reserved for equestrians by Augustus, though most ranked below the senatorial posts. In the imperial administration, equestrian posts included that of the governorship (''praefectus Augusti'') of the province of Egypt, which was considered the most prestigious of all the posts open to ''equites'', often the culmination of a long and distinguished career serving the state. In addition, ''equites'' were appointed to the governorship (''procurator Augusti'') of some smaller provinces and sub-provinces e.g. Judaea, whose governor was subordinate to the governor ofSyria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

.

Equestrians were also the chief financial officers (also called '' procuratores Augusti'') of the imperial provinces, and the deputy financial officers of senatorial provinces. At Rome, equestrians filled numerous senior administrative posts such as the emperor's secretaries of state (from the time of Claudius, e.g. correspondence and treasury) and the '' praefecti annonae'' (director of grain supplies).

In the military, equestrians provided the '' praefecti praetorio'' (commanders of the Praetorian Guard) who also acted as the emperor's chiefs of military staff. There were normally two of these, but at times irregular appointments resulted in just a single incumbent or even three at the same time. Equestrians also provided the '' praefecti classis'' (admirals commanding) of the two main imperial fleets at Misenum in the bay of Naples and at Ravenna on the Italian Adriatic coast. The command of Rome's fire brigade and minor constabulary, the '' vigiles'', was likewise reserved for ''equites''.

Not all ''equites'' followed the conventional career-path. Those equestrians who specialised in a legal or administrative career, providing judges (''iudices'') in Rome's law courts and state secretaries in the imperial government, were granted dispensation from military service by Emperor Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

(r. AD 117–138). At the same time, many ''equites'' became career military officers, remaining in the army for much longer than 10 years. After completing their ''tres militiae'', some would continue to command auxiliary regiments, moving across units and provinces.

Already wealthy to start with, ''equites equo publico'' accumulated even greater riches through holding their reserved senior posts in the administration, which carried enormous salaries (although they were generally smaller than senatorial salaries). For example, the salaries of equestrian ''procuratores'' (fiscal and gubernatorial) ranged from 15,000 to a maximum of 75,000 ''denarii'' (for the governor of Egypt) per annum, whilst an equestrian ''praefectus'' of an auxiliary cohort was paid about 50 times as much as a common foot soldier (about 10,000 ''denarii''). A ''praefectus'' could thus earn in one year the same as two of his auxiliary rankers combined earned during their entire 25-year service terms.

Relations with the emperor

It was suggested by ancient writers, and accepted by many modern historians, that Roman emperors trusted equestrians more than men of senatorial rank, and used the former as a political counterweight to the senators. According to this view, senators were often regarded as potentially less loyal and honest by the emperor, as they could become powerful enough, through the command of provincial legions, to launch coups. They also had greater opportunities for peculation as provincial governors. Hence the appointment of equestrians to the most sensitive military commands. In Egypt, which supplied much of Italy's grain needs, the governor and the commanders of both provincial legions were drawn from the equestrian order, since placing a senator in a position to starve Italy was considered too risky. The commanders of the Praetorian Guard, the principal military force close to the emperor at Rome, were also usually drawn from the equestrian order. Also cited in support of this view is the appointment of equestrian fiscal ''procuratores'', reporting direct to the emperor, alongside senatorial provincial governors. These would supervise the collection of taxes and act as watchdogs to limit opportunities for corruption by the governors (as well as managing the imperial estates in the province). According to Talbert, however, the evidence suggests that ''equites'' were no more loyal or less corrupt than senators. For example, c. 26 BC, the equestrian governor of Egypt, Cornelius Gallus, was recalled for politically suspect behaviour and sundry other misdemeanours. His conduct was deemed sufficiently serious by the Senate to warrant the maximum penalty of exile and confiscation of assets. Under Tiberius, both the senatorial governor and the equestrian fiscal procurator ofAsia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

province were convicted of corruption.

There is evidence that emperors were as wary of powerful ''equites'' as they were of senators. Augustus enforced a tacit rule that senators and prominent equestrians must obtain his express permission to enter the province of Egypt, a policy that was continued by his successors. Also, the command of the Praetorian Guard was normally split between two ''equites'', to reduce the potential for a successful ''coup d'état''. At the same time, command of the second military force in Rome, the ''cohortes urbanae'', was entrusted to a senator.

Oligarchical rule in the early Principate (to 197 AD)

Because the Senate was limited to 600 members, ''equites'' ''equo publico'', numbering several thousands, greatly outnumbered men of senatorial rank. Even so, senators and ''equites'' combined constituted a tiny elite in a citizen-body of about 6 million (in 47 AD) and an empire with a total population of 60–70 million. This immensely wealthy elite monopolised political, military and economic power in the empire. It controlled the major offices of state, command of all military units, ownership of a significant proportion of the empire's arable land (e.g., underNero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

(), half of all land in Africa Proconsularis province was owned by just six senators) and of most major commercial enterprises.

Overall, senators and ''equites'' cooperated smoothly in the running of the empire. In contrast to the chaotic civil wars of the late Republic, the rule of this tiny oligarchy achieved a remarkable degree of political stability. In the first 250 years of the Principate (30 BC – 218 AD), there was only a single episode of major internal strife: the civil war of 68–69.

Equestrian hierarchy

It seems that from the start the equestrians in the imperial service were organised on a hierarchical basis reflecting their pay-grades. According to Suetonius, writing in the early part of the second century AD, the equestrian procurators who "performed various administrative duties throughout the empire" were from the time of Emperor Claudius I organised into four pay-grades, the ''trecenarii'' the ''ducenarii'', the ''centenarii'', and the ''sexagenarii'', receiving 300,000, 200,000, 100,000, and 60,000 sesterces per annum respectively. Cassius Dio, writing a century later, attributed the beginnings of this process to the first emperor, Augustus, himself. There is almost no literary or epigraphic evidence for the use of these ranks until towards the end of the 2nd century. However, it would seem that the increasing employment of equestrians by the emperors in civil and military roles had had social ramifications for it is then that there begin to appear the first references to a more far-reaching hierarchy with three distinct classes covering the whole of the order: the ''Viri Egregii'' (Select Men); the ''Viri Perfectissimi'' ("Best of Men"); and the ''Viri Eminentissimi'' ("Most Eminent of Men"). The mechanisms by which the equestrians were organised into these classes and the distinctions enforced is not known. However, it is generally assumed that the highest class, the ''Viri Eminentissimi'', was confined to the '' Praetorian prefects'', while the ''Viri Perfectissimi'' were the heads of the main departments of state, and the great prefectures, including Egypt, the city watch (''vigiles''), the corn supply (''annona'') etc. and men commissioned to carry out specific tasks by the emperor himself such as the military '' duces''. The defining characteristic of the ''perfectissimate'' seems to have been that its members were of or associated socially (i.e. as ''clientes'' - see Patronage in ancient Rome of Great Men) with the imperial court circle and were office-holders known to the emperor and appointed by his favour. It is also possible that system was intended to indicate the hierarchy of office-holders in situations where this might be disputed. The ''Viri Egregii'' comprehended the rest of the Equestrian Order, in the service of the emperors. The ''Viri Egregii'' included officials of all four pay-grades. ''Ducenariate'' procurators governing provinces not reserved for senators were of this category, as were the ''praefecti legionum'', after Gallienus opened all legionary commands to equestrians. However, it seems that after 270 AD the ''procuratores ducenarii'' were elevated into the ranks of the ''Viri Perfectissimi''.Equestrians in the later Empire (AD 197–395)

Rise of the military equestrians (3rd century)

The 3rd century saw two major trends in the development of the Roman aristocracy: the progressive takeover of the top positions in the empire's administration and army by military equestrians and the concomitant exclusion of the Italian aristocracy, both senators and ''equites'' and the growth in hierarchy within the aristocratic orders. Augustus instituted a policy, followed by his successors, of elevating to the ''ordo equester'' the '' primus pilus'' (chief centurion) of each legion, at the end of his single year in the post. This resulted in about 30 career-soldiers, often risen from the ranks, joining the order every year. These ''equites primipilares'' and their descendants formed a section of the order that was quite distinct from the Italian aristocrats who had become nearly indistinguishable from their senatorial counterparts. They were almost entirely provincials, especially from the Danube provinces where about half the Roman army was deployed. These Danubians mostly came from Pannonia, Moesia, Thrace, Illyria and Dalmatia. They were generally far less wealthy than the landowning Italians (not benefiting from centuries of inherited wealth) and they rarely held non-military posts. Their professionalism led emperors to rely on them ever more heavily, especially in difficult conflicts such as theMarcomannic Wars

The Marcomannic Wars () were a series of wars lasting from about AD 166 until 180. These wars pitted the Roman Empire against principally the Germanic peoples, Germanic Marcomanni and Quadi and the Sarmatian Iazyges; there were related conflicts ...

(166–180). But because they were only equestrians, they could not be appointed to the top military commands, those of '' legatus Augusti pro praetore'' (governor of an imperial province, where virtually all military units were deployed) and '' legatus legionis'' (commander of a legion). In the later 2nd century, emperors tried to circumvent the problem by elevating large numbers of ''primipilares'' to senatorial rank by ''adlectio''.

This met resistance in the Senate, so that in the 3rd century, emperors simply appointed equestrians directly to the top commands, under the fiction that they were only temporary substitutes (''praeses pro legato''). Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

() appointed ''primipilares'' to command the three new legions that he raised in 197 for his Parthian War, Legio I, II & III Parthica Gallienus () completed the process by appointing ''equites'' to command all the legions. These appointees were mostly provincial soldier-equestrians, not Italian aristocrats.

Under the reforming emperor Diocletian (), himself an Illyrian equestrian officer, the military equestrian "takeover" was brought a stage further, with the removal of hereditary senators from most administrative, as well as military posts. Hereditary senators were limited to administrative jobs in Italy and a few neighbouring provinces (Sicily, Africa, Achaea and Asia), despite the fact that senior administrative posts had been greatly multiplied by the tripling of the number of provinces and the establishment of dioceses (super-provinces). The exclusion of the old Italian aristocracy, both senatorial and equestrian, from the political and military power that they had monopolised for many centuries was thus complete. The senate became politically insignificant, although it retained great prestige.

The 3rd and 4th centuries saw the proliferation of hierarchical ranks within the aristocratic orders, in line with the greater stratification of society as a whole, which became divided into two broad classes, with discriminatory rights and privileges: the ''honestiores'' (more noble) and ''humiliores'' (more base). Among the ''honestiores'', equestrians were divided into five grades, depending on the salary-levels of the offices they held.

These ranged from ''egregii'' or ''sexagenarii'' (salary of 60,000 '' sesterces'' = 15,000 ''denarii'') to the ''eminentissimi'' (most exalted), limited to the two commanders of the Praetorian Guard and, with the establishment of Diocletian's Tetrarchy, the four ''praefecti praetorio'' (not to be confused with the commanders of the Praetorian Guard in Rome) that assisted the tetrarchs, each ruling over a quarter of the empire.

Idle aristocracy (4th century)

From the reign of Constantine the Great () onwards, there was an explosive increase in the membership of both aristocratic orders. Under Diocletian, the number of sitting members of the Senate remained at around 600, the level it had retained for the whole duration of the Principate. Constantine establishedConstantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

as a twin capital of the empire, with its own senate, initially of 300 members. By 387, their number had swollen to 2,000, while the Senate in Rome probably reached a comparable size, so that the upper order reached total numbers similar to the ''equo publico'' ''equites'' of the early Principate. By this time, even some commanders of military regiments were accorded senatorial status.

At the same time the order of ''equites'' was also expanded vastly by the proliferation of public posts in the late empire, most of which were now filled by equestrians. The Principate had been a remarkably slim-line administration, with about 250 senior officials running the vast empire, relying on local government and private contractors to deliver the necessary taxes and services. During the 3rd century the imperial bureaucracy, all officials and ranks expanded. By the time of the '' Notitia Dignitatum'', dated to 395 AD, comparable senior positions had grown to approximately 6,000, a 24-fold increase. The total number enrolled in the imperial civilian service, the ''militia inermata'' ('unarmed service') is estimated to have been 30–40,000: the service was professionalized with a staff made up almost entirely of free men on salary, and enrolled in a fictional legion, I Audiutrix.

In addition, large numbers of '' decuriones'' (local councillors) were granted equestrian rank, often obtaining it by bribery. Officials of ever lower rank were granted equestrian rank as reward for good service, e.g. in 365, the '' actuarii'' (accountants) of military regiments. This inflation in the number of ''equites'' inevitably led to the debasement of the order's prestige. By 400 AD, ''equites'' were no longer an echelon of nobility, but just a title associated with mid-level administrative posts.

Constantine established a third order of nobility, the ''comites'' (companions (of the emperor), singular form ''comes

''Comes'' (plural ''comites''), translated as count, was a Roman title, generally linked to a comitatus or comital office.

The word ''comes'' originally meant "companion" or "follower", deriving from "''com-''" ("with") and "''ire''" ("go"). Th ...

'', the origin of the medieval noble rank of count). This overlapped with senators and ''equites'', drawing members from both. Originally, the ''comites'' were a highly exclusive group, comprising the most senior administrative and military officers, such as the commanders of the ''comitatus'', or mobile field armies. But ''comites'' rapidly followed the same path as ''equites'', being devalued by excessive grants until the title became meaningless by 450.

In the late 4th and in the 5th century, therefore, the senatorial class at Rome and Constantinople became the closest equivalent to the ''equo publico'' equestrian class of the early Principate. It contained many ancient and illustrious families, some of whom claimed descent from the aristocracy of the Republic, but had, as described, lost almost all political and military power. Nevertheless, senators retained great influence due to their enormous inherited wealth and their role as the guardians of Roman tradition and culture.

Centuries of capital accumulation, in the form of vast landed estates (''latifundia'') across many provinces resulted in enormous wealth for most senators. Many received annual rents in cash and in kind of over 5,000 lbs of gold, equivalent to 360,000 '' solidi'' (or 5 million Augustan-era ''denarii''), at a time when a ''miles'' (common soldier) would earn no more than four ''solidi'' a year in cash. Even senators of middling wealth could expect an income 1,000–1,500 lbs of gold.

The 4th-century historian Ammianus Marcellinus, a former high-ranking military staff officer who spent his retirement years in Rome, bitterly attacked the Italian aristocracy, denouncing their extravagant palaces, clothes, games and banquets and above all their lives of total idleness and frivolity. In his words can be heard the contempt for the senatorial class of a career soldier who had spent his lifetime defending the empire, a view clearly shared by Diocletian and his Illyrian successors. But it was the latter who reduced the aristocracy to that state, by displacing them from their traditional role of governing the empire and leading the army.

Notes

See also

* Praetorian Guard * Publican * Hippeus * MedjayReferences

Bibliography

Ancient

* * * * * * } * * *Modern

* * ** ** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * *External links

* * {{Authority control Social classes in ancient Rome Types of cavalry unit in the army of ancient Rome Cavalry units and formations of ancient Rome Latin words and phrases