Epítome De La Conquista Del Nuevo Reino De Granada on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' (English: ''Summary of the conquest of the New Kingdom of Granada'') is a document of uncertain authorship, possibly (partly) written by

''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' (English: ''Summary of the conquest of the New Kingdom of Granada'') is a document of uncertain authorship, possibly (partly) written by

From ''La Tora'', Jiménez de Quesada sent the ships further upriver, for another 20 ''leguas'', until it became impossible to continue. The indigenous (''yndios'') here didn't live on the river banks, but on small islands. Because of the impossible trajectory along the river, Jiménez de Quesada agreed to ascend over land "on his left hand", climbing a mountain range that later became known as the Sierras del Opón. The consumption of salt is described as coming from Santa Marta along the river for "70 leguas" and so far from the coast the grainy salt was expensive and only available to the highest social classes. The rest of the salt came from urine or palm trees. Higher up, the salt was different; came in loafs, much like sugar loafs.

The salt of this type was less expensive and the conquistadors concluded that the grainy salt went up the river, while the better salt came from higher altitudes down the river. The indigenous people who carried the salt, told the conquistadors that it was coming from a land of richness. This led the Spanish uphill, on the ''Camino de la Sal'' ("The Salt Route") to search for its source. At this point, the Sierras del Opón were crossed and the brigantines returned to the coast, leaving the majority of the soldiers with De Quesada because many of his troops had died already during the expedition. The route over the Sierras del Opón is described as rugged and little populated by natives, a journey of various days and 50 ''leguas'' long. In the sparse settlements, the conquistadors found great quantities of the high quality salts and after a while they had crossed the difficult mountainous area, reaching a flatter terrain, described as "what would become the New Kingdom of Granada". It is described that the people of this area were different and also spoke a different language from the people along the Magdalena River and of the Sierras del Opón, making it impossible to understand them at first. Over time, it became possible to communicate and the people in the flatter area, called ''San Gregorio'' provided the conquistadors with

From ''La Tora'', Jiménez de Quesada sent the ships further upriver, for another 20 ''leguas'', until it became impossible to continue. The indigenous (''yndios'') here didn't live on the river banks, but on small islands. Because of the impossible trajectory along the river, Jiménez de Quesada agreed to ascend over land "on his left hand", climbing a mountain range that later became known as the Sierras del Opón. The consumption of salt is described as coming from Santa Marta along the river for "70 leguas" and so far from the coast the grainy salt was expensive and only available to the highest social classes. The rest of the salt came from urine or palm trees. Higher up, the salt was different; came in loafs, much like sugar loafs.

The salt of this type was less expensive and the conquistadors concluded that the grainy salt went up the river, while the better salt came from higher altitudes down the river. The indigenous people who carried the salt, told the conquistadors that it was coming from a land of richness. This led the Spanish uphill, on the ''Camino de la Sal'' ("The Salt Route") to search for its source. At this point, the Sierras del Opón were crossed and the brigantines returned to the coast, leaving the majority of the soldiers with De Quesada because many of his troops had died already during the expedition. The route over the Sierras del Opón is described as rugged and little populated by natives, a journey of various days and 50 ''leguas'' long. In the sparse settlements, the conquistadors found great quantities of the high quality salts and after a while they had crossed the difficult mountainous area, reaching a flatter terrain, described as "what would become the New Kingdom of Granada". It is described that the people of this area were different and also spoke a different language from the people along the Magdalena River and of the Sierras del Opón, making it impossible to understand them at first. Over time, it became possible to communicate and the people in the flatter area, called ''San Gregorio'' provided the conquistadors with

The lands crossing the Sierras del Opón consisted of valleys (on the

The lands crossing the Sierras del Opón consisted of valleys (on the

Jiménez de Quesada left Bogotá and went to ''Coçontá'' (

Jiménez de Quesada left Bogotá and went to ''Coçontá'' (

The people, and especially the women, from the New Kingdom are described as highly religious and beautiful in faces and body shapes; less brown than "the other indigenous that we have seen". The women wore white, black and colourful dresses that covered their bodies from breast to feet instead of the capes and mantles seen with other natives (''Yndias''). On their heads they wore

The people, and especially the women, from the New Kingdom are described as highly religious and beautiful in faces and body shapes; less brown than "the other indigenous that we have seen". The women wore white, black and colourful dresses that covered their bodies from breast to feet instead of the capes and mantles seen with other natives (''Yndias''). On their heads they wore

The

The

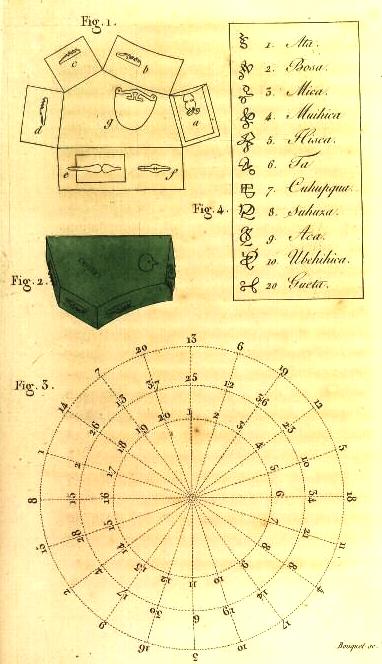

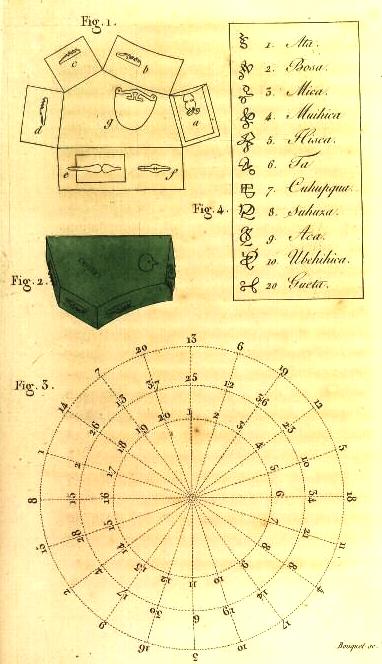

The conscience of time is specified as years and months well divided, with during the first ten days of the months a habit of eating

The conscience of time is specified as years and months well divided, with during the first ten days of the months a habit of eating

The

The

The dead, as reported in ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'', are buried in two ways; in Tunja the main members of society are not buried, yet their intestines taken out, wrapped in cloths, and adorned with gold and emeralds placed on slightly elevated beds in special dedicated ''bohíos'' and left there forever. The other way of treating the deceased Muisca is in Bogotá, where they are buried or thrown into the deepest lakes after putting them in coffins filled with gold and emeralds.''Epítome'', p.95

The ideas about the

The dead, as reported in ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'', are buried in two ways; in Tunja the main members of society are not buried, yet their intestines taken out, wrapped in cloths, and adorned with gold and emeralds placed on slightly elevated beds in special dedicated ''bohíos'' and left there forever. The other way of treating the deceased Muisca is in Bogotá, where they are buried or thrown into the deepest lakes after putting them in coffins filled with gold and emeralds.''Epítome'', p.95

The ideas about the

The ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' contains a number of words transcribed or taken from Muysccubun.''Epítome''

The ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' contains a number of words transcribed or taken from Muysccubun.''Epítome''

- Muysccubun Dictionary Online Examples are ''moscas'' ( muysca),''muysca''

- Muysccubun ''Bogotá'' ( Muyquyta),''Muyquyta''

- Muysccubun ''

- Muysccubun '' Sumindoco'', ''uchíes''; combination of ''u-'' (

- Muysccubun''chíe''

- Muysccubun ''fucos'' ( fuquy),''fuquy''

- Muysccubun ''

- Muysccubun and ''yomas'' ( iome; ''Solanum tuberosum'').''iome''

- Muysccubun The word written as ''hayo'' probably refers to the Ika word ''

Colombian-Jewish-Ukrainian

Colombian-Jewish-Ukrainian

-

- Colciencias She concludes the work is written by

''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' (English: ''Summary of the conquest of the New Kingdom of Granada'') is a document of uncertain authorship, possibly (partly) written by

''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' (English: ''Summary of the conquest of the New Kingdom of Granada'') is a document of uncertain authorship, possibly (partly) written by Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada y Rivera, also spelled as Ximénez and De Quezada, (;1496 16 February 1579) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador in northern South America, territories currently known as Colombia. He explored the territory named ...

between 1548 and 1559. The book was not published until 1889 by anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

Marcos Jiménez de la Espada

Marcos Jiménez de la Espada (1831–1898) was a Spanish zoologist, herpetologist, explorer and writer, born in Cartagena, Spain, although he spent most of his life in Madrid, where he died. He is known for participating in the Pacific Scientif ...

in his work ''Juan de Castellanos y su Historia del Nuevo Reino de Granada''.

''Epítome'' narrates about the Spanish conquest of the Muisca

The Spanish conquest of the Muisca took place from 1537 to 1540. The Muisca were the inhabitants of the central Andean highlands of Colombia before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors. They were organised in a loose confederation of differe ...

, from the start from Santa Marta in April 1536 to the leave of main conquistador Jiménez de Quesada in April 1539 from Bogotá, arriving to Spain, about "The Salt People" (Muisca

The Muisca (also called Chibcha) are an indigenous people and culture of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia, that formed the Muisca Confederation before the Spanish conquest. The people spoke Muysccubun, a language of the Chibchan langu ...

) encountered in the conquest expedition in the heart of the Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

n Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

, their society, rules, religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

, handling of the dead, warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

and neighbouring "cannibalistic" Panche.

The text has been studied by various authors over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, mainly by Juan Friede

Juan Friede Alter (Wlava, Russian Empire, 17 February 1901 - Bogotá, Colombia, 28 June 1990) was a Ukrainian-Colombian historian of Jewish descent who is recognised as one of the most important writers about Colombian history, the Spanish conq ...

and modern scholars

A scholar is a person who pursues academic and intellectual activities, particularly academics who apply their intellectualism into expertise in an area of study. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher ...

and various theories about authorship and temporal setting have been proposed. The document is held by the National Historical Archive

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, Spain.

Contents

The document is written in old Spanish in the present tense and first person with descriptions of Jiménez de Quesada, written as Ximénez de Quesada, in the third person. The margins of the main texts are notes with sometimes difficult to discern text, vagued in time.Ramos Pérez, 1972, p.283The route from the coast to ''La Tora''

''Epítome'' starts with a description of the Caribbean coastal area where the expeditionSpanish conquest of the Muisca

The Spanish conquest of the Muisca took place from 1537 to 1540. The Muisca were the inhabitants of the central Andean highlands of Colombia before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors. They were organised in a loose confederation of differe ...

started. The author speaks of the Magdalena River

The Magdalena River ( es, Río Magdalena, ; less commonly ) is the main river of Colombia, flowing northward about through the western half of the country. It takes its name from the biblical figure Mary Magdalene. It is navigable through much of ...

, dividing the Spanish provinces of Cartagena to the west and Santa Marta

Santa Marta (), officially Distrito Turístico, Cultural e Histórico de Santa Marta ("Touristic, Cultural and Historic District of Santa Marta"), is a city on the coast of the Caribbean Sea in northern Colombia. It is the capital of Magdalena ...

to the east. In the document, the Magdalena River is also called ''Río Grande'', thanks to the great width of the river close to Santa Marta. A description of the journey over the river is given where the heavy and frequent rains made it impossible to disembark the ships (brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Older ...

s). According to the ''Epítome'', the Spanish could not ascend further than Sompallón. The distance unit used, is the ''legua'' (league

League or The League may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Leagues'' (band), an American rock band

* ''The League'', an American sitcom broadcast on FX and FXX about fantasy football

Sports

* Sports league

* Rugby league, full contact footba ...

), an old and poorly defined unit of distance varying from to .''Epítome'', p.81

On the second page, the rich gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

en burial sites

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

of the Zenú

The ''Zenú'' or ''Sinú'' is a pre-Columbian culture in Colombia, whose ancestral territory comprises the valleys of the Sinú and San Jorge rivers as well as the coast of the Caribbean around the Gulf of Morrosquillo. These lands lie within t ...

are described, as well as the routes inland from later Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, that was conquered by German conquistadors. The next paragraph narrates about the start of the main expedition inland from Santa Marta, leaving the city in the month of April 1536. It is said Gonzalo Ximénez de Quesada left with 600 men, divided into 8 groups of infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

, 10 groups of cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

and a number of brigs on the Magdalena River. De Quesada and his troops marched over land on the bank of the river. Names of the captains in the army of De Quesada are given as ''San Martín'', ''Céspedes'', ''Valençuela'', ''Lázaro Fonte'', ''Librixa'', ''de Junco'' and ''Suarex''. The captains heading the brigs are named as (Francisco Gómez del) ''Corral'', ''Cardosso'' and ''Albarracín''. The troops went out of free will and consent of the governor of Santa Marta, Pedro de Lugo. The troops went under command of Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada.''Epítome'', p.82 The third page describes that the troops spent more than a year and more than 100 ''leguas'' on their journey. They reached ''La Tora'' resent-day Barrancabermeja">Barrancabermeja.html" ;"title="resent-day Barrancabermeja">resent-day Barrancabermeja farther than any soldier had gone before, after 150 ''leguas''. The expedition took so long because of the waters and the narrow passages of the surrounding area.''Epítome'', p.83

''El Camino de la Sal''

From ''La Tora'', Jiménez de Quesada sent the ships further upriver, for another 20 ''leguas'', until it became impossible to continue. The indigenous (''yndios'') here didn't live on the river banks, but on small islands. Because of the impossible trajectory along the river, Jiménez de Quesada agreed to ascend over land "on his left hand", climbing a mountain range that later became known as the Sierras del Opón. The consumption of salt is described as coming from Santa Marta along the river for "70 leguas" and so far from the coast the grainy salt was expensive and only available to the highest social classes. The rest of the salt came from urine or palm trees. Higher up, the salt was different; came in loafs, much like sugar loafs.

The salt of this type was less expensive and the conquistadors concluded that the grainy salt went up the river, while the better salt came from higher altitudes down the river. The indigenous people who carried the salt, told the conquistadors that it was coming from a land of richness. This led the Spanish uphill, on the ''Camino de la Sal'' ("The Salt Route") to search for its source. At this point, the Sierras del Opón were crossed and the brigantines returned to the coast, leaving the majority of the soldiers with De Quesada because many of his troops had died already during the expedition. The route over the Sierras del Opón is described as rugged and little populated by natives, a journey of various days and 50 ''leguas'' long. In the sparse settlements, the conquistadors found great quantities of the high quality salts and after a while they had crossed the difficult mountainous area, reaching a flatter terrain, described as "what would become the New Kingdom of Granada". It is described that the people of this area were different and also spoke a different language from the people along the Magdalena River and of the Sierras del Opón, making it impossible to understand them at first. Over time, it became possible to communicate and the people in the flatter area, called ''San Gregorio'' provided the conquistadors with

From ''La Tora'', Jiménez de Quesada sent the ships further upriver, for another 20 ''leguas'', until it became impossible to continue. The indigenous (''yndios'') here didn't live on the river banks, but on small islands. Because of the impossible trajectory along the river, Jiménez de Quesada agreed to ascend over land "on his left hand", climbing a mountain range that later became known as the Sierras del Opón. The consumption of salt is described as coming from Santa Marta along the river for "70 leguas" and so far from the coast the grainy salt was expensive and only available to the highest social classes. The rest of the salt came from urine or palm trees. Higher up, the salt was different; came in loafs, much like sugar loafs.

The salt of this type was less expensive and the conquistadors concluded that the grainy salt went up the river, while the better salt came from higher altitudes down the river. The indigenous people who carried the salt, told the conquistadors that it was coming from a land of richness. This led the Spanish uphill, on the ''Camino de la Sal'' ("The Salt Route") to search for its source. At this point, the Sierras del Opón were crossed and the brigantines returned to the coast, leaving the majority of the soldiers with De Quesada because many of his troops had died already during the expedition. The route over the Sierras del Opón is described as rugged and little populated by natives, a journey of various days and 50 ''leguas'' long. In the sparse settlements, the conquistadors found great quantities of the high quality salts and after a while they had crossed the difficult mountainous area, reaching a flatter terrain, described as "what would become the New Kingdom of Granada". It is described that the people of this area were different and also spoke a different language from the people along the Magdalena River and of the Sierras del Opón, making it impossible to understand them at first. Over time, it became possible to communicate and the people in the flatter area, called ''San Gregorio'' provided the conquistadors with emerald

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium.Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr. and Kammerling, Robert C. (1991) ''Gemology'', John Wiley & Sons, New York, p ...

s.''Epítome'', p.84 Jiménez de Quesada asked the people where they were coming from and the natives pointed him to the ''Valle de los Alcázares'' (Bogotá savanna

The Bogotá savanna is a montane savanna, located in the southwestern part of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the center of Colombia. The Bogotá savanna has an extent of and an average altitude of . The savanna is situated in the Eastern Range ...

), upon which the troops headed that way. They encountered a "king" they called ''Bogothá'' who gave the conquistadors many golden objects to expel the Spanish from his lands and the indigenous people told the Spanish the emeralds were coming from lands belonging to the "king" of Tunja

Tunja () is a city on the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes, in the region known as the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, 130 km northeast of Bogotá. In 2018 it had a population of 172,548 inhabitants. It is the capital of Boyacá department an ...

.''Epítome'', p.85

Entering Muisca territory

The lands crossing the Sierras del Opón consisted of valleys (on the

The lands crossing the Sierras del Opón consisted of valleys (on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense () is a high plateau located in the Eastern Cordillera of the Colombian Andes covering parts of the departments of Cundinamarca and Boyacá. The altiplano corresponds to the ancient territory of the Muisca. The Alti ...

), where each valley was ruled by a different person. The valleys were densely populated and around the valleys (to the west) lived indigenous people who were called ''Panches

The Panche or Tolima is an indigenous group of people in what is now Colombia. Their language is unclassified – and possibly unclassifiable – but may have been Cariban. They inhabited the southwestern parts of the department of Cundinamarca a ...

''. They consumed human flesh, while the people from the New Kingdom of Granada (i.e. Muisca

The Muisca (also called Chibcha) are an indigenous people and culture of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia, that formed the Muisca Confederation before the Spanish conquest. The people spoke Muysccubun, a language of the Chibchan langu ...

, called ''moxcas'') did not perform cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

. Also the difference in climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorologic ...

is reported; the Panche lived in warm climates while the Muisca lived in cold or temperate climates. ''Epítome'' describes the extent of the New Kingdom as "130 leguas, more or less, long" and "30 leguas, in some parts 20 wide". The Kingdom is divided into two provinces; that of Tunja and of Bogotá (modern names are used). The document describes that the rulers

A ruler, sometimes called a rule, line gauge, or scale, is a device used in geometry and technical drawing, as well as the engineering and construction industries, to measure distances or draw straight lines.

Variants

Rulers have long ...

have surnames referring to the terrain and are "very powerful" and have ''cacique

A ''cacique'' (Latin American ; ; feminine form: ''cacica'') was a tribal chieftain of the Taíno people, the indigenous inhabitants at European contact of the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles, and the northern Lesser Antilles. The term is a Spa ...

s'' who are subject to their reign. The population is described as approximately "70,000 in the Bogotá area, that is larger" and about "40,000 in the smaller and less powerful Tunja province". The relation between Tunja and Bogotá is described as filled with many and ancient wars

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

. According to the ''Epítome'', the people from the Bogotá area had long-standing wars with the Panche, that lived closer to them than to the people from the Tunja province.

From Funza to Hunza

Jiménez de Quesada left Bogotá and went to ''Coçontá'' (

Jiménez de Quesada left Bogotá and went to ''Coçontá'' (Chocontá

Chocontá is a municipality and town of Colombia in the Almeidas Province, part of the department of Cundinamarca. It is located on the Pan-American Highway. In 1938 Chocontá had a population of 2,041.

Etymology

In the Chibcha language of the ...

), that he called ''Valle del Spiritusancto''. From there he went to Turmequé

Turmequé is a town and municipality in the Colombian Department of Boyacá, part of the subregion of the Márquez Province. Turmequé is located at northeast from the capital Bogotá. The municipality borders Ventaquemada in the west, in the ...

in a valley he named ''Valle de la Trompeta'', the first of the Tunja lands. From Turmequé he send his men to discover the emerald mines and after that leaving for another valley, of San Juan, in Muysccubun called ''Tenesucha'' and from there to the valley of Somondoco

Somondoco is a town and municipality in the Colombian Department of Boyacá. This town and larger municipal area are located in the Valle de Tenza. The Valle de Tenza is the ancient route connecting the Altiplano Cundiboyacense and the Llanos ...

where he spoke to the ''cacique Sumindoco'', who governed the mines or quarries of emeralds and was subject to the ''gran cacique'' of Tunja. Many emeralds were extracted. He decided to continue to search for the ''cacique'' of Tunja, who was at war with the Christians. The document describes the lands of Tunja as richer than those of Bogotá, although those were already rich, but gold and precious emeralds are more abundant in Tunja. In total 1800 emeralds, large and small were found and De Quesada had never seen so many and precious ones in his life. The rich resources of Peru are described in relation to the mines of Tunja, where the emeralds were more numerous than in Peru. ''Epítome'' describes the process of extracting the emeralds with wooden sticks from the veins in the rocks.''Epítome'', p.87 From the emerald mines of Tunja, he returned to Bogotá.''Epítome'', p.86

Reception of the conquistadors by the Muisca

''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' continues with a description of how the indigenous people received and saw the conquistadors. The people experienced great fears seeing the Spanish, and saw them as children of the deities Sun (Sué

Sué, Xué, Sua, Zuhe or Suhé was the deity, god of the Sun in the Muisca religion and mythology, religion of the Muisca. He was married to Moon goddess Chía (goddess), Chía.Ocampo López, 2013, Ch.4, p.33 The Muisca people, Muisca and their Mu ...

) and Moon ( Chía). The people believed, according to ''Epítome'', they were sent to punish the people for their sins. Hence they named the Spanish ''usachíes''; a combination of ''Usa'', referring to the Sun and ''Chíe'' to the Moon as "children of the Sun and the Moon". The document narrates that the Muisca women climbed the hills surrounding the valleys and threw their infants to the Spanish, some from their breasts, to stop the fury of the gods. It is described that the people very much feared the horses, and only bit by bit got used to them. ''Epítome'' says that the people started to attack the Spanish, but were easily beaten because they feared the horses so much and fled. The text describes this as the common practice in the battles of the indigenous people (''bárbaros'') against the conquistadors during all of 1537 and part of 1538, until they finally bowed to the reign of his Majesty, the King of Spain.''Epítome'', p.88

The Panche

The description of the Panche is different in ''Epítome'' than the Muisca; the Panche are described as a much more war-like people, their rugged terrain worse for the cavalry and the style of warfare different. While the Muisca "fought" using screams and shouting, the Panche are described as fighting silently withslingshot

A slingshot is a small hand-powered projectile weapon. The classic form consists of a Y-shaped frame, with two natural rubber strips or tubes attached to the upper two ends. The other ends of the strips lead back to a pocket that holds the pro ...

s, poisoned arrows and large heavy poles made of palm trees (''macanas'') swinging them with both hands to hit their enemies. The practice, later described from the Muisca as well, of tieing mummies

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay furth ...

on their backs is reported from the Panche. The habit is described as showing what will happen to their opponents; fighting like they fought and to instigate fear in the enemy. Of the Panche is described that when they won their battles, they celebrated their victory with festivities, took the children of their enemies to sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exi ...

them, captured the women and killed the men by poking out the eyes of the combat leaders. The combat of the Panche is described as fiercer as of the Muisca and the combatants walked naked. They had tubes made of animal skins where they held the lances and bow and arrows to shoot. The Panche warriors are described as eating the flesh of their enemies at the battlefield or later at home with their wives and children. The process of treaties is described as performed not by the men, but by the women, as "they cannot be refused".''Epítome'', p.89

Descriptions of society

The people, and especially the women, from the New Kingdom are described as highly religious and beautiful in faces and body shapes; less brown than "the other indigenous that we have seen". The women wore white, black and colourful dresses that covered their bodies from breast to feet instead of the capes and mantles seen with other natives (''Yndias''). On their heads they wore

The people, and especially the women, from the New Kingdom are described as highly religious and beautiful in faces and body shapes; less brown than "the other indigenous that we have seen". The women wore white, black and colourful dresses that covered their bodies from breast to feet instead of the capes and mantles seen with other natives (''Yndias''). On their heads they wore garland

A garland is a decorative braid, knot or wreath of flowers, leaves, or other material. Garlands can be worn on the head or around the neck, hung on an inanimate object, or laid in a place of cultural or religious importance.

Etymology

From the ...

s (''guirnaldas'') of cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

, decorated with flowers. The ''caciques'' wore hats ('' bonetes'') made of cotton. The wives of the ''caciques'' wore a type of kofia

KOFIA or kofia may refer to:

*Korea Financial Investment Association, a self-regulatory body in South Korea

*Kofia (hat), a brimless hat similar to a fez

{{disambiguation ...

on their heads. The climate and daytime is described as roughly the same all year round and the architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

of the houses as made of wood. The houses of the ''caciques'' are located behind various circular posts, described in ''Epítome'' as "a labyrinth of Troy". The houses were surrounded by large patios and painted walls.''Epítome'', p.90

Cuisine

The

The cuisine

A cuisine is a style of cooking characterized by distinctive ingredients, techniques and dishes, and usually associated with a specific culture or geographic region. Regional food preparation techniques, customs, and ingredients combine to ...

of the Muisca is described as mainly consisting of maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

and yuca

''Manihot esculenta'', commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated a ...

, with other food coming from farther away. Plantation of the various tubers

Tubers are a type of enlarged structure used as storage organs for nutrients in some plants. They are used for the plant's perennation (survival of the winter or dry months), to provide energy and nutrients for regrowth during the next growing s ...

was arranged in multiple ways. The infinite supply of salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quantitie ...

is described in ''Epítome'', extracted from wells on the Bogotá savanna n Zipaquirá, Nemocón">Zipaquirá.html" ;"title="n Zipaquirá">n Zipaquirá, Nemocón and other places] and made into loafs of salt. The salt was traded up until the north, the Sierras del Opón and until the Magdalena River, as earlier described. The meat of the people consisted of white-tailed deer, deer, that is described to have been in great quantities, "like livestock in Spain". Other meat were eastern cottontail, rabbits, also in large quantities, and named ''fucos''. ''Epítome'' names those "rabbits" also existed in Santa Marta and other parts, where they were called ''curíes'' (guinea pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy (), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus ''Cavia'' in the family Caviidae. Breeders tend to use the word ''cavy'' to describe the ani ...

s). Poultry is named as pigeon

Columbidae () is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with short necks and short slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. They primarily ...

s and ducks, that are raised in the many lakes. The diet is supplied further with fish, described as only one species and small, "only one or two handpalms long", but of a good taste.

Penalties, position of ''caciques'' and marriage

The penal system of the Muisca is described as "moral" and of "medium reason", because the offenses are punished "very well". ''Epítome'' describes "there are more gallows than in Spain" with people hanging between two posts with arms, feet and hair attached to them. The Muisca are described as cutting hands, noses and ears for "not so serious crimes". Shaming happened to the higher social classes, where hair and pieces of the clothing were cut. The respect for the ''caciques'' is told to have been "enormous", as the people didn't look them in the face and when a ''cacique'' enters, the people turned and inclined showing him their backs. When the "Bogothá" (''zipa

When the Spanish arrived in the central Colombian highlands, the region was organized into the Muisca Confederation, which had two rulers; the ''zipa'' was the ruler of the southern part and based in Muyquytá. The ''hoa'' was the ruler of the n ...

'') spit, the people caught his saliva in cotton bowls, to prevent it from hitting the ground.''Epítome'', p.91

When the people were marrying, the men are reported to not organise festivities, but simply take the women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or Adolescence, adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female hum ...

home. Polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

is noted; "the men could marry as many women as they wanted, given that they could maintain them"; so some had ten wives and others twenty. Of the "Bogothá" is stated that "he had more than 400 wives". Marrying first degree relatives was forbidden and in some parts second degree marriages too. Heritage of rule was not the sons of the former ''cacique'', but the siblings and if they didn't have or lived, the sons of the brother or sister of the deceased ''cacique''.

Time-keeping and preparation for young ''caciques''

The conscience of time is specified as years and months well divided, with during the first ten days of the months a habit of eating

The conscience of time is specified as years and months well divided, with during the first ten days of the months a habit of eating coca

Coca is any of the four cultivated plants in the family Erythroxylaceae, native to western South America. Coca is known worldwide for its psychoactive alkaloid, cocaine.

The plant is grown as a cash crop in the Argentine Northwest, Bolivia, Al ...

(''hayo''). The next ten days are for working the farmfields and houses

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

. The last ten days are described as time when people rest and the women live separately from the men; all the women together in one ''bohío'' and every man in his own. It is reported that in other parts of the New Kingdom of Granada, the division of time is different; the described ten day periods are longer and two months of the year are reserved for fasting

Fasting is the abstention from eating and sometimes drinking. From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see " Breakfast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after ...

(''quaresma'').''Epítome'', p.92

To prepare for the ''cacicazgo'', the young boys and girls are held solitary in houses for some years, depending on the role they will fulfill in society. They are incarcerated for seven years in small spaces without a view of the Sun and given delicacies at certain times. Only the people caring for the children are allowed access to the space and they torture them. After their imprisonment, the children are allowed to wear golden jewels; nosepieces and earrings. The people are also described as wearing breast plates, golden mitre

The mitre (Commonwealth English) (; Greek: μίτρα, "headband" or "turban") or miter (American English; see spelling differences), is a type of headgear now known as the traditional, ceremonial headdress of bishops and certain abbots in ...

s (''mitras'') and bracelets. ''Epítome'' reports the people lost themselves in music, singing and dances, one of their greatest pleasures. The author calls the people "lying very much, they never tell the truth". The goldworking

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Nowadays they mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, goldsmiths have also made silverware, platters, goblets, decorative and serviceabl ...

and weaving

Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal th ...

by the Muisca is described as "the first not as well as the people from New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

and the second not as well as the people from Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

".

Religion, sacrifice and warfare

The

The religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

of the Muisca is reported as very important and they constructed in each settlement a temple, with many others scattered across the area

Area is the quantity that expresses the extent of a region on the plane or on a curved surface. The area of a plane region or ''plane area'' refers to the area of a shape

A shape or figure is a graphics, graphical representation of an obje ...

, accessible by roads

A road is a linear way for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles (motorized and non-motorized) and pedestrians. Unlike streets, the main function of roads is transportation.

There are many types of ...

and isolated. The sacred places are lavishly adorned with gold and emeralds

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium.Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr. and Kammerling, Robert C. (1991) ''Gemology'', John Wiley & Sons, New York, p. ...

. The process of sacrifices

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

is described as happening with blood, water and fire. Birds are killed and their blood runs over the temples, their heads hanging from the sides of the holy places. Water running through pipes also is used as a sacrifice. Fire and aromatic smoke is used in the temples, too. The religious rituals are reported to be accompanied with singing.

It is described the Muisca did not sacrifice humans for religious purposes, yet in two other ways. When the Panche were beaten, the boys who were presumed still being virgin were taken and sacrificed. The ritual passed with screams and the heads of the victims were hanged on the posts of their ''bohíos''. The other way would be to sacrifice the young boys by priests 'chyquy''near the temples.''Epítome'', p.93

''Epítome'' reports the young boys called ''moxas'', taken from a place called ''Casa del Sol'' at thirty ''leguas'' from the New Kingdom. They are carried on the shoulders and stay seven to eight years in the temples to be sacrificed afterwards. The process is described as cutting their heads off and letting the blood flow over the sacred sites. The boys have to be virgins, as if they are not, their blood is not considered pure enough to serve as sacrifice. Before going to war, the guecha warriors are described to stay one month in a temple, with people outside singing and dancing and the Muisca honouring Sué and Chía. The warriors sleep and eat little during this time. After the battles, the people perform the same ritual for various days and when the warriors are defeated, they also do this to lament the losses.

During these rituals, the people are described to burn certain herbs, called ''Jop'' (yopo

''Anadenanthera peregrina'', also known as yopo, jopo, cohoba, parica or calcium tree, is a perennial tree of the genus ''Anadenanthera'' native to the Caribbean and South America. It grows up to tall, and has a horny bark. Its flowers grow ...

) and ''Osca'' (''hosca''; tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

) in ''Epítome'', inhaling the smoke and putting those herbs on the joints of their bodies. When certain joints are moving it would be a sign of luck in warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

and when others move, it means bad luck.

The sacred sites of the Muisca consist of forests and lakes, according to ''Epítome'', where the people bury gold and emeralds and throw those precious resources in the lakes. The people do not cut the trees of the sacred woods but bury their dead

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

there. The Sun and Moon are considered husband and wife and are celebrated as the creators of things. Apart from that, the people have various other gods, "much like our panishsaints", honoured in temples throughout the area. On top of that, the people all have personal idols, called in ''Epítome'' ''Lares'' (''tunjo

A ''tunjo'' (from Muysccubun: ''chunso'') is a small anthropomorh or zoomorph figure elaborated by the Muisca as part of their art. ''Tunjos'' were made of gold or ''tumbaga''; a gold-silver-copper alloy. The Muisca used their ''tunjos'' ...

s''). They are described as small figures made of fine gold with emeralds in their bellies. It is described the people wore those on their arms and when going to battle, having them in one hand and the weapons in the other, "especially in the province of Tunja where the people are more religious."''Epítome'', p.94

The dead and afterlife

The dead, as reported in ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'', are buried in two ways; in Tunja the main members of society are not buried, yet their intestines taken out, wrapped in cloths, and adorned with gold and emeralds placed on slightly elevated beds in special dedicated ''bohíos'' and left there forever. The other way of treating the deceased Muisca is in Bogotá, where they are buried or thrown into the deepest lakes after putting them in coffins filled with gold and emeralds.''Epítome'', p.95

The ideas about the

The dead, as reported in ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'', are buried in two ways; in Tunja the main members of society are not buried, yet their intestines taken out, wrapped in cloths, and adorned with gold and emeralds placed on slightly elevated beds in special dedicated ''bohíos'' and left there forever. The other way of treating the deceased Muisca is in Bogotá, where they are buried or thrown into the deepest lakes after putting them in coffins filled with gold and emeralds.''Epítome'', p.95

The ideas about the afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving ess ...

of the Muisca is described as "barbaric" and "confused" in terms of the immortality of the soul. The people who have been good in life would have great pleasures and rest after their death, while those who were bad during their lifetime would have a lot of work and be punished with lashes. The guecha who died in warfare and the women dying when giving birth would have access to the same right of rest and pleasures, "although they were bad in life".

In contrast to the spiritual life of the Muisca, the Panche are described as immoral, as they only care about their crimes and vices. ''Epítome'' narrates they do not care about gold or other precious things of life, yet only about war, pleasure and eating human flesh, the only reason to invade the New Kingdom. In other parts of the Panche territories, "close to Tunja across two fast flowing rivers", it is noted that the people eat ants

Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cretaceous period. More than 13,800 of an estimated total of 22,00 ...

and make bread of the insects. The ants (''hormiga culona'', still a delicacy in Santander

Santander may refer to:

Places

* Santander, Spain, a port city and capital of the autonomous community of Cantabria, Spain

* Santander Department, a department of Colombia

* Santander State, former state of Colombia

* Santander de Quilichao, a m ...

) are described as available in great quantities, some small, but mostly large. The people of the region kept them as livestock enclosed by large leaves.

Return to Spain of the conquest leaders

The period of conquest of the New Kingdom of Granada is reported in ''Epítome'' to have taken most of 1538. This period resulted in the creation of three main cities; the province of Bogotá in the city of " Santa Fee", the province of Tunja in the city with the same name and the later founded city of Vélez, where the conquistadors entered afterwards. The conquest is said to have been completed in the year 1539, when Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada ("El Licenciado") returned to Spain to report to the King and claim his rewards. ''Epítome'' describes that Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada left the reign of the New Kingdom in the hands of his brother,Hernán Pérez de Quesada

Hernán Pérez de Quesada, sometimes spelled as Quezada, (c. 1515 – 1544) was a Spanish conquistador. Second in command of the army of his elder brother, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, Hernán was part of the first European expedition towar ...

, and traveled along the Magdalena River

The Magdalena River ( es, Río Magdalena, ; less commonly ) is the main river of Colombia, flowing northward about through the western half of the country. It takes its name from the biblical figure Mary Magdalene. It is navigable through much of ...

(''Río Grande'') using brigs to not have to cross the strenuous Sierras del Opón again, the way he reached Bogotá.''Epítome'', p.96

It is described that "one month before this leave" from Venezuela came Nicolás Fedreman ic captain under Jorge Espira, governor of the province of Venezuela for the Germans, with news about natives from very rich lands. He brought 150 men with him. During the same period, some fifteen days later, came from Peru Sebastián de Venalcázar, captain under Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

, and brought 100 soldiers and the same news. The three commanders laughed about their three years so close to each other. ''Epítome'' describes that Jiménez de Quesada took all of the soldiers of De Federman and half of those of De Benalcázar to refresh his troops and sent them to the settlements of the New Kingdom to populate the area. The other half of De Benalcázar's men he sent (back) to the province between the New Kingdom and Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

, called Popayán

Popayán () is the capital of the Colombian departments of Colombia, department of Cauca Department, Cauca. It is located in southwestern Colombia between the Cordillera Occidental (Colombia), Western Mountain Range and Cordillera Central (Colo ...

, of which De Benalcázar was governor. Federmann and some of his men accompanied De Quesada in his journey along the Magdalena River to the coast and back to Spain. ''Epítome'' reports they arrived there in November 1539, when the Spanish King was crossing France to reach Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

.

On the last page of ''Epítome'' it is said that the ''Licenciado'' had differences of opinion with Alonso de Lugo, married to Beatriz de Noroña, sister of María de Mendoza, wife of the great commander De Léon. The disagreements were about the reign over the New Kingdom, because De Lugo and his son had the governance over Santa Marta

Santa Marta (), officially Distrito Turístico, Cultural e Histórico de Santa Marta ("Touristic, Cultural and Historic District of Santa Marta"), is a city on the coast of the Caribbean Sea in northern Colombia. It is the capital of Magdalena ...

. It is described that his icMajesty created a Royal Chancillery in the year 1547 icwith ''oídores'' in charge of the New Kingdom. The name of the New Kingdom of Granada was given by Jiménez de Quesada based on the Kingdom of Granada

)

, common_languages = Official language:Classical ArabicOther languages: Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic, Berber, Ladino

, capital = Granada

, religion = Majority religion:Sunni IslamMinority religions:Roman C ...

"here" (in Spain), that showed similiraties in size, topography and climate.''Epítome'', p.97

The text notes that Jiménez de Quesada received for his efforts of conquering and populating the New Kingdom the title ''Mariscal'' and 2000 ducats for him and his descendants for the reign of the New Kingdom. For the natives of the New Kingdom another 8000 ducats were provided as well as an annual fee of 400 ducats for the mayor of Bogotá

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well as ...

.

The closing paragraph of ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' concludes with the description of the family of Jiménez de Quesada as son of Gonçalo Ximénez and Ysabel de Quesada, living in the city of Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

and originating from Córdoba.

Source for Muysccubun

The ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' contains a number of words transcribed or taken from Muysccubun.''Epítome''

The ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' contains a number of words transcribed or taken from Muysccubun.''Epítome''- Muysccubun Dictionary Online Examples are ''moscas'' ( muysca),''muysca''

- Muysccubun ''Bogotá'' ( Muyquyta),''Muyquyta''

- Muysccubun ''

Tunja

Tunja () is a city on the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes, in the region known as the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, 130 km northeast of Bogotá. In 2018 it had a population of 172,548 inhabitants. It is the capital of Boyacá department an ...

'' (Chunsa),''Chunsa''- Muysccubun '' Sumindoco'', ''uchíes''; combination of ''u-'' (

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

) and ''chíe'' (Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

),''sua''- Muysccubun''chíe''

- Muysccubun ''fucos'' ( fuquy),''fuquy''

- Muysccubun ''

yopo

''Anadenanthera peregrina'', also known as yopo, jopo, cohoba, parica or calcium tree, is a perennial tree of the genus ''Anadenanthera'' native to the Caribbean and South America. It grows up to tall, and has a horny bark. Its flowers grow ...

'', ''Osca'' ('' hosca''),''hosca''- Muysccubun and ''yomas'' ( iome; ''Solanum tuberosum'').''iome''

- Muysccubun The word written as ''hayo'' probably refers to the Ika word ''

hayu

The Hayus ( ne, हायु) are a member of the Kirat tribe speaking their own language, Wayu or Hayu. Little is known about them. They are Animist by religion. According to the 2001 Nepal census, there are 1821 Hayu in the country, of whi ...

''.

Inconsistencies

Colombian-Jewish-Ukrainian

Colombian-Jewish-Ukrainian scholar

A scholar is a person who pursues academic and intellectual activities, particularly academics who apply their intellectualism into expertise in an area of study. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researche ...

Juan Friede

Juan Friede Alter (Wlava, Russian Empire, 17 February 1901 - Bogotá, Colombia, 28 June 1990) was a Ukrainian-Colombian historian of Jewish descent who is recognised as one of the most important writers about Colombian history, the Spanish conq ...

(1901-1990) has listed inconsistencies that were analysed by Enrique Otero D'Costa in the document:Descubrimiento del Nuevo Reino de Granada y Fundación de Bogotá - ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada''-

Juan Friede

Juan Friede Alter (Wlava, Russian Empire, 17 February 1901 - Bogotá, Colombia, 28 June 1990) was a Ukrainian-Colombian historian of Jewish descent who is recognised as one of the most important writers about Colombian history, the Spanish conq ...

- Banco de la República

The Bank of the Republic ( es, Banco de la República) is the central bank of Colombia. It was initially established under the regeneration era in 1880. Its main modern functions, under the new Colombian constitution were detailed by Congress a ...

* ''Epítome'' describes the death of Pedro Fernández de Lugo, governor of Santa Marta, during the preparation of the conquest expedition, while this happened months after De Quesada had left Santa MartaFriede, 1960, p.93

* Alonso Luis de Lugo is named as the acting governor, while he left the government in 1544

* The achievements of Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada are described as ''mariscal'', ''regidor'' and 2000 ducats in rent, events that didn't happen until 1547 and 1548

* The existence of the Royal Audience (''Audiencia Real'') is described, that took place in 1550

Friede compared the work ''Gran Cuaderno'' by Jiménez de Quesada and concluded the descriptions were identical. ''Gran Cuaderno'' was handed over to Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (August 14781557), commonly known as Oviedo, was a Spanish soldier, historian, writer, botanist and colonist. Oviedo participated in the Spanish colonization of the West Indies, arriving in the first few year ...

, who included the contents in his ''Historia general y natural de las Indias'' of 1535 (expanded, from his notes, in 1851).

Theories about authorship

''Epítome'' has produced a number of reviewing articles, books and other texts since the first publication by Jiménez de la Espada in 1889. Enrique Otero D'Costa has attributed parts of ''Epítome'' to Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, written in 1539, and other parts to other people, unrelated to the conquistador. Friede concludes these errors not definitive; he maintains the ''Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada'' is written in its totality in the years 1548 to 1549, when Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada was in Spain.Friede, 1960, p.94 Researcher Fernando Caro Molina concluded in 1967 that only minor parts were written by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada.Caro Molina, 1967, p.130 Carmen Millán de Benavides wrote an article in 2014, a book in 2001, and her PhD thesis about the document in 1997.''Curriculum Vitae'' Carmen Millán de Benavides- Colciencias She concludes the work is written by

Alonso de Santa Cruz

Alonzo de Santa Cruz (or Alonso, Alfonso) (1505 – 1567) was a Spanish cartographer, mapmaker, instrument maker, historian and teacher. He was born about 1505, and died in November 1567. His maps were inventoried in 1572.

Alonzo de Santa Cruz wa ...

(1505-1567), cosmographer

The term cosmography has two distinct meanings: traditionally it has been the protoscience of mapping the general features of the cosmos, heaven and Earth; more recently, it has been used to describe the ongoing effort to determine the large-scal ...

who worked for the kings Carlos II

Charles II of Spain (''Spanish: Carlos II,'' 6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700), known as the Bewitched (''Spanish: El Hechizado''), was the last Habsburg ruler of the Spanish Empire. Best remembered for his physical disabilities and the War of ...

and Felipe II.Millán de Benavides, 2014, p.11 She describes the ''Epítome'' as a fragmentary text, not a narrative.Millán de Benavides, 2014, p.14 The abbreviations used in the text, led her to conclude it was a scribble text, not meant for direct publication.Millán de Benavides, 2014, p.15

Manuel Lucena Salmoral wrote in an article in 1962 that the document was written by an unknown writer, none of the authors suggested by other researchers.Caro Molina, 1967, p.117 Also Javier Vergara y Velasco maintains the document is written entirely by someone else.Millán de Benavides, 2001, p.27

See also

*List of conquistadors in Colombia

This is a list of conquistadors who were active in the conquest of terrains that presently belong to Colombia. The nationalities listed refer to the state the conquistador was born into; Granada and Castile are currently part of Spain, but were s ...

*Spanish conquest of the Muisca

The Spanish conquest of the Muisca took place from 1537 to 1540. The Muisca were the inhabitants of the central Andean highlands of Colombia before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors. They were organised in a loose confederation of differe ...

*''El Dorado

El Dorado (, ; Spanish for "the golden"), originally ''El Hombre Dorado'' ("The Golden Man") or ''El Rey Dorado'' ("The Golden King"), was the term used by the Spanish in the 16th century to describe a mythical tribal chief (''zipa'') or king o ...

''

*Hernán Pérez de Quesada

Hernán Pérez de Quesada, sometimes spelled as Quezada, (c. 1515 – 1544) was a Spanish conquistador. Second in command of the army of his elder brother, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, Hernán was part of the first European expedition towar ...

, Baltasar Maldonado

Baltasar Maldonado, also written as Baltazar Maldonado,

– Bank of the Republic (Colombia), Banco ...

, Juan de Céspedes

*– Bank of the Republic (Colombia), Banco ...

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada y Rivera, also spelled as Ximénez and De Quezada, (;1496 16 February 1579) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador in northern South America, territories currently known as Colombia. He explored the territory named ...

, ''El Carnero

''El Carnero'' ( en, The Sheep) is the colloquial name of a Spanish language colonial chronicle whose title was ''Conquista i descubrimiento del nuevo reino de Granada de las Indias Occidentales del mar oceano, i fundacion de la ciudad de San ...

'', ''Elegías de varones ilustres de Indias

''Elegías de varones ilustres de Indias'' is an epic poem written in the late sixteenth century by Juan de Castellanos.

Description

The work gives a detailed account of the colonization of the Caribbean and the territories in present-day Colom ...

''

References

The work

*Bibliography

* * * * *Other works about the conquest

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Epitome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada 16th-century books 1889 books Colombian books Spanish-language books Books published posthumously Works of uncertain authorship History of the Muisca History of Colombia