Eppa Hunton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

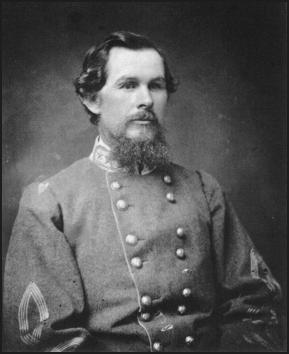

Eppa Hunton II (September 24, 1822October 11, 1908) was a Virginia lawyer and soldier who rose to become a brigadier general in the

In February 1861, Prince William County voters elected Hunton, an avowed

In February 1861, Prince William County voters elected Hunton, an avowed

After the war Hunton resumed his former law practice in northern Virginia, initially in Prince William County as well as Fauquier and Loudoun, but by year's end moved his family to Warrenton, where he bought a house in 1867. He later noted that two servant girls (one of whom he had bought so she would not be sold away from her family) had accompanied his wife and family to and from Lynchburg, so that after returning from prison, he told them they were free, and paid their stage fare from Clarke County to their family in Alexandria.

As Hunton's career restarted, he also returned to politics, opposing

After the war Hunton resumed his former law practice in northern Virginia, initially in Prince William County as well as Fauquier and Loudoun, but by year's end moved his family to Warrenton, where he bought a house in 1867. He later noted that two servant girls (one of whom he had bought so she would not be sold away from her family) had accompanied his wife and family to and from Lynchburg, so that after returning from prison, he told them they were free, and paid their stage fare from Clarke County to their family in Alexandria.

As Hunton's career restarted, he also returned to politics, opposing

Afterward, Hunton again resumed his law practice in

Afterward, Hunton again resumed his law practice in

The Political Graveyard

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20050213210032/http://www.pwcgov.org/docLibrary/PDF/002509.pdf Prince William County, Virginia Reliquary

Detailed biography taken from ''Confederate Military History'', Vol. III''Civil Rights–"The world is governed too much"''

- speech given on February 3, 1875, House of Representatives, 43rd Congress, 2nd Session

- speech given on December 13, 1894, on the Bill (S. No. 1708) to Establish the University of the United States

Hunton & Williams law firm

listing the dates of birth and death. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hunton, Eppa 2 1822 births 1908 deaths Confederate States Army brigadier generals People of Virginia in the American Civil War Fauquier County, Virginia, in the American Civil War Prince William County, Virginia, in the American Civil War Burials at Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, Virginia) People from Warrenton, Virginia Democratic Party United States senators from Virginia Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia Virginia Secession Delegates of 1861 American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law People from Brentsville, Virginia Southern Historical Society members United States senators who owned slaves Members of the United States House of Representatives who owned slaves Eppa 2 19th-century members of the United States House of Representatives 19th-century United States senators

Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fi ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. After the war, he served as a Democrat in both the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

and then the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

.

Early years

Hunton was born on September 24, 1822 nearWarrenton, Virginia

Warrenton is a town in Fauquier County, Virginia, United States. It is the county seat. The population was 10,057 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, an increase from 9,611 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census and 6,670 at ...

, to Eppa Hunton I

Eppa Hunton (January 30, 1789 – April 8, 1830) was an American planter, military officer, and politician.

Early life and family Childhood

Hunton was born on January 30, 1789, at "Fairview" in Fauquier County, Virginia, the second of eight ch ...

(1789–1830) and the former Elizabeth Marye Brent (1789–1866), who had married on June 22, 1811, in Fauquier County

Fauquier County is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 72,972. The county seat is Warrenton.

Fauquier County is in Northern Virginia and is a part of the Washington metropolitan area.

History ...

. He was their third son, after the twins John Heath Hunton and George William Hunton, who were born in 1826. Both families had emigrated from England in the 17th century. The Brent family had moved across the Potomac River from Maryland before Bacon's Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion by Virginia settlers that took place from 1676 to 1677. It was led by Nathaniel Bacon against Colonial Governor William Berkeley, after Berkeley refused Bacon's request to drive Native American India ...

and by the time of the Revolutionary War were important planters and lawyers in Stafford County, Virginia

Stafford County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is approximately south of Washington, D.C. It is part of the Northern Virginia region, and the D.C area. It is one of the fastest-growing and highest-income counties in ...

and western area's of the Northern Neck proprietary (and the only prominent somewhat Catholic family in Virginia, with Robert Brent becoming the first mayor of the District of Columbia

The mayor of the District of Columbia is the head of the executive branch of the government of the District of Columbia. The mayor has the duty to enforce district laws, and the power to either approve or veto bills passed by the D.C. Council. ...

). The Huntons had initially settled in Lancaster County, Virginia

Lancaster County is a county located on the Northern Neck in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population sits at 10,919. Its county seat is Lancaster.

Located on the Northern Neck near the mouth of the Rappahanno ...

before moving to what became eastern Fauquier County, Virginia near its border with Prince William County

Prince William County lies beside the Potomac River in the Commonwealth of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 482,204, making it Virginia's second most populous county. The county seat is the independent city of Manassas. A part ...

, Virginia (now the Buckland Historic District). His man's father taught school and operated three plantations: "Springfield" and " Mount Hope" in Fauquier County (whose seat was Warrenton, though the plantations were near New Baltimore, which became the family graveyard) and another in nearby Prince William County

Prince William County lies beside the Potomac River in the Commonwealth of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 482,204, making it Virginia's second most populous county. The county seat is the independent city of Manassas. A part ...

. The senior Eppa Hunton had fought in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

under his cousin Thomas Hunton, who led a Fauquier County cavalry troop of the 5th Brigade, 2nd Regiment before rising to the rank of Brigadier General of that brigade in 1819, as well as winning election to the Virginia House of Delegates 1803-1808 and 1813-1814, but who died in 1826. The elder Eppa Hunton appeared likely to have a similar career, becoming the brigade inspector and twice won election to the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two houses of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-numbe ...

, but died unexpectedly young in Lancaster

Lancaster may refer to:

Lands and titles

*The County Palatine of Lancaster, a synonym for Lancashire

*Duchy of Lancaster, one of only two British royal duchies

*Duke of Lancaster

*Earl of Lancaster

*House of Lancaster, a British royal dynasty

...

in 1830. This left his widow to raise nine young children (two others having died as infants), and the Prince William plantation was sold to pay debts. His mother's father, William Brent, was a lawyer who had fought in the American Revolutionary War, and had moved his family from the port of Dumfries

Dumfries ( ; ; from ) is a market town and former royal burgh in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, near the mouth of the River Nith on the Solway Firth, from the Anglo-Scottish border. Dumfries is the county town of the Counties of Scotland, ...

in Prince William County to Bealeton in Fauquier County for safekeeping during that war. The Prince William county seat, Brentsville (near the county's center), was named for that family. This Eppa Hunton was educated at the private New Baltimore Academy by Rev. John Ogilvie, although family circumstances forced him to borrow money to finish his final year in 1839.

Early career

After graduating from that school, this Eppa Hunton taught for three years, first in a log schoolhouse near The Plains in Fauquier County. Then he opened his own school in Buckland in Prince William County, where he lived with his brotherSilas

Silas or Silvanus (; Greek: Σίλας/Σιλουανός; fl. 1st century AD) was a leading member of the Early Christian community, who according to the New Testament accompanied Paul the Apostle on his second missionary journey.

Name and ...

and his wife. Hunton taught the five sons of John Webb Tyler, who in turn helped him to study law and become admitted to the Virginia bar in 1843. Hunton thus began his legal practice

Legal practice is sometimes used to distinguish the body of judicial or administrative precedents, rules, policies, customs, and doctrines from legislative enactments such as statutes and constitutions which might be called "laws" in the strict ...

in Brentsville, the Prince William County seat. He also became prominent in the local community, winning election as colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

, and later brigadier general, in the Virginia militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

.

After Virginia's legislature elected J.W. Tyler as circuit judge, Hunton was elected his successor as Commonwealth's attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, county prosecutor, state attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or solicitor is the chief prosecutor or chief law enforcement officer represen ...

(local prosecutor) in 1848. Voters re-elected him twice, so he served from 1849–1861. In 1850, this Eppa Hunton, at age 30, owned six slaves: a 30-year-old black woman and five children (a 14-year-old mulatto girl, five- and ten-year-old black boys, and three-year-old and five-month-old black girls).

Hunton later described himself as a Democrat from his "earliest youth" like his father, and he was one of Virginia's delegates to the Democratic National Convention in 1856, and was a Breckenridge elector in 1860, later describing the multiple conventions that year that divided the Democratic party.

Family life

In 1848, Eppa Hunton married Lucy Caroline Weir (February 20, 1825 – September 4, 1899), daughter of Robert and Clara Boothe Weir. Her family could trace their ancestry to Judge Benjamin Waller ofWilliamsburg

Williamsburg may refer to:

Places

*Colonial Williamsburg, a living-history museum and private foundation in Virginia

*Williamsburg, Brooklyn, neighborhood in New York City

*Williamsburg, former name of Kernville (former town), California

*Williams ...

, and her father had been a successful merchant in Tappahannock before moving to Prince William County and running a plantation called "Hartford" until he died in 1840, leaving his widow with young children. During the April after Lucy's marriage to Eppa Hunton, Mrs. Weir sold "Hartford" and moved with her daughters Betty and Martha to the new home Hunton had purchased in Brentsville. There she lived with the young family until Union soldiers destroyed the home in 1862. Mrs. Weir would continue to live with the Huntons until her death in Warrenville in 1870, and Martha until her death in 1882, although Betty would move in with relatives in Clarke County after Lucy's death.

The Huntons had two children:

:*Elizabeth Boothe Hunton (June 20, 1853 – September 30, 1854)

:* Eppa Hunton III (commonly known as "Eppa Hunton Jr.;" April 14, 1855 – March 5, 1932), who became his father's law partner, and went on to co-found the notable Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

law firm Hunton & Williams

Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP, formerly known as Hunton & Williams LLP and commonly known as Hunton, is an American law firm. The firm adopted its current name on April 2, 2018, when it merged with Andrews Kurth Kenyon LLP.

Andrews Kurth Kenyon p ...

in 1901.

Considerably after the Civil War described below, Hunton's brother James died, and Eppa Hunton provided for his children, especially Bessie Marye Hunton (named after their mother), paying for her education and ultimately blessing her marriage.

Civil War

In February 1861, Prince William County voters elected Hunton, an avowed

In February 1861, Prince William County voters elected Hunton, an avowed secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

ist, as their delegate to the Virginia Secession Convention, as he handily defeated a Unionist candidate, Allen Howison. At the Convention Hunton made many contacts which proved important later in his career, from former U.S. President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

, to Governor John Letcher

John Letcher (March 29, 1813January 26, 1884) was an American lawyer, journalist, and politician. He served as a Representative in the United States Congress, was the 34th Governor of Virginia during the American Civil War, and later served in ...

, Lt. Gov. Montague, and former Navy Secretary Ballard Preston.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Hunton relinquished his militia commission and secured a commission

In-Commission or commissioning may refer to:

Business and contracting

* Commission (remuneration), a form of payment to an agent for services rendered

** Commission (art), the purchase or the creation of a piece of art most often on behalf of anot ...

as colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

of the 8th Virginia Infantry, Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the Military forces of the Confederate States, military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) duri ...

, composed of seven companies from Loudoun County

Loudoun County () is in the northern part of the Virginia, Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. In 2020, the census returned a population of 420,959, making it Virginia's third-most populous county. The county seat is Leesburg, Virgi ...

, two from Fauquier County and one each from Fairfax County and Prince William County. Initially, Charles B. Tebbs was his lieutenant colonel and Norborne Berkeley as the regimental major. The regiment (then of eight companies) was assigned to guard the Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

in Loudoun County, along with the Loudoun Cavalry and a Loudoun artillery regiment. During the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run, called the Battle of First Manassas

. by Confederate States ...

on July 21, 1861, Gen. . by Confederate States ...

P.G.T. Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 – February 20, 1893) was an American military officer known as being the Confederate general who started the American Civil War at the battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is comm ...

cited its gallantry coming off reserve status in his summary of the Confederate victory. It was then again assigned to protect Leesburg, Virginia

Leesburg is a town in and the county seat of Loudoun County, Virginia, United States. It is part of both the Northern Virginia region of the state and the Washington metropolitan area, including Washington, D.C., the nation's capital.

European se ...

, the seat of Loudoun County and an important crossroads for trade across the Potomac River as well as across the Blue Ridge Mountains. Although General Beauregard refused to let Col. Hunton take leave to visit his sick wife five miles from that battlefield, Hunton received several leaves from duty during the war due to a fistula which failed to heal, despite various surgeries, until he became a prisoner of war during the war's final days. In October his regiment was part of Nathan G. Evans' brigade near Leesburg, where the temporarily recovered Hunton led his command against a Union force at Ball's Bluff, driving it into the Potomac River. Captains William N. Berkeley and Edmond Berkeley were also cited for their enthusiasm, and for his initiative in capturing about 325 Union prisoners local farmer E.V. White (a/k/a Lige White) would soon be promoted to captain (and ultimately to colonel).

In 1862 the regiment left the Centreville area to oppose the Union's Peninsular Campaign. With the confederate evacuation of Northern Virginia Huntons hometown got under union occupation and he had to evacuate his family through Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in Virginia, United States. It is the seat of government of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Quee ...

to Lynchburg. Despite still suffering from fistula Hunton returned from sick leave to command his regiment from the withdrawal under Yorktown to defend Richmond. Hunton missed both the Battle of Williamsburg

The Battle of Williamsburg, also known as the Battle of Fort Magruder, took place on May 5, 1862, in York County, James City County, and Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the first pitc ...

and the Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War.

The Union's Army of the Po ...

due to sickness. Anticipating the Seven Days Battles he disregarded his physician's advise and returned to the army to fight at the Battle of Frazier's Farm and Battle of Gaines' Mill

The Battle of Gaines' Mill, sometimes known as the Battle of Chickahominy River, took place on June 27, 1862, in Hanover County, Virginia, as the third of the Seven Days Battles which together decided the outcome of the Union's

Peninsula Campaig ...

(which Hunton later cited as the unit's most gallant charge). On August 21, 1862, the regiment fought at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

. Hunton's regiment then crossed the Potomac River and as he again returned to duty fought at the South Mountain and the bloody Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgin ...

. After retreating to Virginia, it returned to fight on December 13 at the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat between the Union Army, Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Major general ( ...

and again the following month, under the command of General Richard B. Garnett

Richard Brooke Garnett (November 21, 1817 – July 3, 1863) was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He was court-martialed by Stonewall Jackson for his actions in command of the Stonewall Brig ...

, although it would miss the Battle of Chancellorville because it was assigned to secure supplies in North Carolina.

Promoted to brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

command late because of his ongoing health issues, Hunton was assigned to Lt. Gen. James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War and was the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Ho ...

's corps, Maj. Gen. George Pickett

George Edward Pickett (January 16,Military records cited by Eicher, p. 428, and Warner, p. 239, list January 28. The memorial that marks his gravesite in Hollywood Cemetery lists his birthday as January 25. Thclaims to have accessed the baptis ...

's division, and the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

. In August 1863, Hunton formally received a promotion to brigadier general, based on his valor during the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was a three-day battle in the American Civil War, which was fought between the Union and Confederate armies between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle, won by the Union, ...

, particularly during Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge was an infantry assault on July 3, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg. It was ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee as part of his plan to break through Union lines and achieve a decisive victory in the North. T ...

in which Hunton received a leg wound. Because of his promotion, Norborne Berkeley was promoted to command the 8th Virginia, and his brother Edmund became the Lieut. Colonel, his brother William Berkeley, Major, and Charles Berkeley became the senior Captain of what then became known as the "Berkeley Regiment." After service in the defenses of Richmond in 1864 including the Battle of Malvern Hill

The Battle of Malvern Hill, also known as the Battle of Poindexter's Farm, was fought on July 1, 1862, between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, led by Gen. Robert E. Lee, and the Union Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. ...

, Gen. Hunton rejoined Pickett's division and fought at Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Army, Union Lieuten ...

and once again defended Richmond and Petersburg siege lines. In March 1865 his command (by then reduced to 1500 men) fought a delaying action at Five Forks, which turned into a rout.

As April 1865 began, Hunton's brigade was again forced to retreat, and skirmished at the Battle of Sayler's Creek

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force c ...

. Hunton surrendered his troops to Union forces (a staff officer of future Gen. George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point ...

) after that skirmish, on April 6, 1865, so he missed General Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House three days later. He and other former Confederate officers alternately took ambulances and marched to City Point, then Petersburg, then Washington, D.C. He and a dozen other former senior officers were in New Jersey en route to Massachusetts when they learned of President Lincoln's assassination and noted the Union officers refused to succumb to mob cries of "hang them" at every station, although he also took umbrage at his companion General Ewell's proposed resolution of the prisoners denying any complicity in the assassination. Hunton recovered his health as a prisoner of war at Fort Warren (Massachusetts), especially noting the professionalism of its commanding officer, a career officer from North Carolina named Wilson, and two local families. He was paroled on July 24. While a prisoner of war, Hunton thought of his lawbooks, as well as worried that his wife and children were penniless in Lynchburg, especially since he had invested all his savings in now-worthless Virginia State Bonds. He learned they refused money offered them by a staff officer of Federal Major John W. Turner (against whom Hunton had fought for many months and found chivalrous), but managed to secure a $50 loan from family friend John H. Reid, then survived on that money until Hunton's brother Silas managed to get to Lynchburg and escorted them to Culpeper, where they stayed with the family of Hunton's sister Elizabeth and brother in law, Lt. Morehead (who had distinguished himself at the Battle of Ball's Bluff).

Post-war politics

After the war Hunton resumed his former law practice in northern Virginia, initially in Prince William County as well as Fauquier and Loudoun, but by year's end moved his family to Warrenton, where he bought a house in 1867. He later noted that two servant girls (one of whom he had bought so she would not be sold away from her family) had accompanied his wife and family to and from Lynchburg, so that after returning from prison, he told them they were free, and paid their stage fare from Clarke County to their family in Alexandria.

As Hunton's career restarted, he also returned to politics, opposing

After the war Hunton resumed his former law practice in northern Virginia, initially in Prince William County as well as Fauquier and Loudoun, but by year's end moved his family to Warrenton, where he bought a house in 1867. He later noted that two servant girls (one of whom he had bought so she would not be sold away from her family) had accompanied his wife and family to and from Lynchburg, so that after returning from prison, he told them they were free, and paid their stage fare from Clarke County to their family in Alexandria.

As Hunton's career restarted, he also returned to politics, opposing Congressional Reconstruction

The Reconstruction era was a period in US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the abolition of slavery and reintegration of the former Confederate Sta ...

and particularly disabilities which the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868

The Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868, was an assembly of delegates elected by the voters to establish the fundamental law of Virginia following the American Civil War and the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. The Convention, w ...

sought to place on former Confederates. The Constitutional Convention was necessary because Virginia's state constitution of 1850 explicitly endorsed slavery, and the constitutional convention during the American Civil War only had representatives from Union-occupied portions of the Commonwealth and was generally disregarded. Based on negotiations with the newly elected president, Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

and successive military governors responsible for Virginia, the election to ratify the new state constitution separately considered the document (which was overwhelmingly ratified by voters) and the disabilities on former Confederates (which were narrowly defeated). Hunton thought the Freedman's Bureau created problems, and that he got along well with Gen. John Schofield

John McAllister Schofield (; September 29, 1831 – March 4, 1906) was an American soldier who held major commands during the American Civil War. He was appointed U.S. Secretary of War (1868–1869) under President Andrew Johnson and later serve ...

, the governor of military district No. 1, as well as the local military judge Lysander Hill.

Hunton was also nominated for the state senate for Fauquier and Rappahannock counties after the war, and may have been elected after the war, but unable to take his seat.

With his disability removed by Presidential pardon, Hunton was elected as a Democrat from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

in November 1872, and served in the 43rd and the three succeeding Congresses (March 4, 1873 – March 4, 1881). He defeated Republican Edward Daniels, a former abolitionist from Massachusetts who had moved into Gunston Hall

Gunston Hall is an 18th-century Georgian architecture, Georgian Plantation house in the Southern United States, mansion near the Potomac River in Mason Neck, Virginia, Mason Neck, Virginia, United States. Built between 1755 and 1759 by George ...

and who later would become a Democrat. During his years as a Representative, Hunton served on the Committee on Military Affairs and voted to exonerate Gen. Custer, who had been kind to him. He noted the "Democratic wave" in the 1874 election, and that while Virginia only sent one other Democrat in 1872, he had seven democratic colleagues in the state delegation in 1874. Hunton became chairman of the Committee on Revolutionary Pensions (44th Congress). In the 46th Congress, he became chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia (although he was disappointed at his removal from the House Judiciary Committee by the new Speaker in the 45th Congress, whom he had supported), and worked across the aisle with Joseph C.S. Blackburn of Kentucky to improve governance of the federal city, both securing passage of a new 3-commissioner system as well as payment of tax arrearages by corporations and others seeking favors from his committee. Hunton was also appointed to lead a committee investigating allegations of corruption involving former Speaker James Blaine, but the controversial investigation ended after Blaine secured possession of some incriminating letters, and soon was elected to the U.S. Senate, thus giving up his House seat and removing the committee's jurisdiction, although the scandal probably lost Blaine his chance for his party's presidential nomination in 1876, which went to Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes served as Cincinnati's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. He was a staunch Abolitionism in the Un ...

instead. Meanwhile, Hunton was the only southerner appointed to the 15-member Electoral Commission created by an act of Congress in 1877 to decide the contests in various states in the presidential election of 1876.

In 1876, Hunton easily defeated Republican J.C. O'Neal, and after a primary challenge by S. Chapman Neale of Alexandria, handily defeated both Republican Mr. Cochran of Culpeper and Greenback Democrat Capt. John R. Carter (his former subordinate, from Loudoun) in 1878. However, he announced that would be his final term in Congress, and declined renomination in 1880, instead resuming his private legal practice, perhaps in part because he was supporting the family of his brother James, who had died in 1877 (including paying for the education of his niece Bessie Marye Hunton) and his son Eppa Hunton Jr. also graduated from the University of Virginia and his father brought him into the legal practice. In addition to practicing with his son in northern Virginia, he established a partnership with Jeff Chandler in Washington, which flourished until Chandler moved to St. Louis.

Railroad executive John S. Barbour Jr. (whose brother James Barbour

James C. Barbour (June 10, 1775 – June 7, 1842) was an American politician, planter, and lawyer. He served as a delegate from Orange County, Virginia, in the Virginia General Assembly and as speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates. He was t ...

of Culpeper had lost to Hunton in the 1874 election as an independent with Mosby's support) succeeded him. John Barbour Jr. served three terms, then won election as Virginia's U.S. Senator, but died after three years in office. On May 28, 1892, Hunton was appointed to fill Barbour's senate seat, and won the subsequently election to fill that vacancy, serving until March 4, 1895. During his term, he was chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee to Establish a University of the United States (1893–1895). However, he was deeply disappointed in President Grover Cleveland, who although a fellow Democrat, undercut and divided the party concerning the tariff, free silver, and other issues.

On or about April 1, 1894, Hunton became indirectly involved in voting bribery attempts. Charles W. Buttz, a lobbyist and claim agent originally from North Dakota

North Dakota ( ) is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota people, Dakota and Sioux peoples. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minneso ...

, but living in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

at the time, went to Hunton's house in Warrenton during the Senator's absence. Buttz told Hunton's son, Eppa III, that he would pay him a contingent fee of $25,000 if he would, by presenting arguments as to the pending tariff bill, induce his father to vote against it. Excerpts from the Senate investigating committee on this issue follow:

This offer was declined at once and peremptorily by Eppa Hunton II as set forth in his testimony, and the whole matter was communicated by him to his father. Senator Hunton availed himself of the first opportunity to disclose the matter to certain of his friends in the senate, as appears in the testimony, and was in no other way connected with the transaction.Buttz also attempted to bribe

South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

James Henderson Kyle to vote against the same bill. Hunton and Kyle were eventually exonerated from all blame.

Hunton remained active in the United Confederate Veterans in his later years. In 1895, the 8th Virginia Regiment held its first reunion at Ball's Bluff, site of one of their triumphs, and Hunton addressed them. In 1902, Virginia judge James Keith presented a portrait of Hunton to the Lee Camp of the UCV in Richmond.

Death and legacy

Afterward, Hunton again resumed his law practice in

Afterward, Hunton again resumed his law practice in Warrenton, Virginia

Warrenton is a town in Fauquier County, Virginia, United States. It is the county seat. The population was 10,057 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, an increase from 9,611 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census and 6,670 at ...

. However, after his wife's death, and his son's remarriage to his first wife's sister, Virginia Payne, he decided better opportunities awaited his son in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

, particularly after the younger Eppa Hunton's participation at the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1902. This Eppa Hunton sold his Warrenton house and gave his son the proceeds to buy a home in Richmond. Hunton wrapped up his final cases from Washington, D.C., wrote his autobiography and lived the rest of his days with the growing young family at 8 Franklin Street in Richmond, grateful that a Richmond doctor had cured his vertigo, unlike the smaller town's doctors. On October 11, 1908, blind and deaf though previously vigorous, Hunton died at his son's home. He was buried in the city's Hollywood Cemetery with his wife Clara and many fellow Confederate veterans.

His name continues to be used within the family, currently by Eppa Hunton VI, who practices law in Richmond. In 1977, Hunton & Williams established the ''Eppa Hunton IV Memorial Book Award'' at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

's School of Law

A law school (also known as a law centre/center, college of law, or faculty of law) is an institution, professional school, or department of a college or university specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for bec ...

, in honor of this Eppa Hunton's grandson (1904–1976), whose baptism the grandfather had witnessed at St. James Episcopal Church in Warrenton. According to the university, the award is "presented annually to a third-year student who has demonstrated unusual aptitude in litigation courses and shown a keen awareness and understanding of the lawyer's ethical and professional responsibility."

Some of his speeches are held at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

in Washington, D.C., among others in the papers of Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

. His home in Warrenton, Brentmoor is a historic site, although perhaps now better known for its links to its builder Judge Edward M. Spilman or for its postwar occupant (and Hunton's predecessor as owner) Confederate Colonel (and Virginia lawyer) John Singleton Mosby

John Singleton Mosby (December 6, 1833 – May 30, 1916), also known by his nickname "Gray Ghost", was an American military officer who was a Confederate cavalry commander in the American Civil War. His command, the 43rd Battalion, Virginia ...

.

His autobiography (which he finished in 1904), originally only for family use and 100 copies of which were printed by his son in 1929, is a perspective on Virginia life in the 19th century.

See also

* List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)References

Books and newspapers

*''The Trenton Times'', Trenton, New Jersey, May 26, 1894. ( Image of article) * Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, ''Civil War High Commands.'' Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. . * Hunton, Eppa. ''The Autobiography of Eppa Hunton.'' Richmond: William Byrd Press, 1933. * Sifakis, Stewart. ''Who Was Who in the Civil War.'' New York: Facts On File, 1988. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders.'' Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. .Websites

The Political Graveyard

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20050213210032/http://www.pwcgov.org/docLibrary/PDF/002509.pdf Prince William County, Virginia Reliquary

External links

Detailed biography taken from ''Confederate Military History'', Vol. III

- speech given on February 3, 1875, House of Representatives, 43rd Congress, 2nd Session

- speech given on December 13, 1894, on the Bill (S. No. 1708) to Establish the University of the United States

Hunton & Williams law firm

listing the dates of birth and death. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hunton, Eppa 2 1822 births 1908 deaths Confederate States Army brigadier generals People of Virginia in the American Civil War Fauquier County, Virginia, in the American Civil War Prince William County, Virginia, in the American Civil War Burials at Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, Virginia) People from Warrenton, Virginia Democratic Party United States senators from Virginia Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia Virginia Secession Delegates of 1861 American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law People from Brentsville, Virginia Southern Historical Society members United States senators who owned slaves Members of the United States House of Representatives who owned slaves Eppa 2 19th-century members of the United States House of Representatives 19th-century United States senators