Epicureanism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Epicureanism is a system of

''Berenice II and the Golden Age of Ptolemaic Egypt''

Oxford University Press, p.33 Some modern Epicureans have argued that Epicureanism is a type of religious identity, arguing that it fulfils Ninian Smart's "seven dimensions of religion", and that the Epicurean practices of feasting on the twentieth and declaring an oath to follow Epicurus, insistence on doctrinal adherence, and the sacredness of Epicurean friendship, make Epicureanism more similar to some non-theistic religions than to other philosophies.

Tetrapharmakos, or "The four-part cure", is Philodemus of Gadara's basic guideline as to how to live the happiest possible life, based on the first four of

Tetrapharmakos, or "The four-part cure", is Philodemus of Gadara's basic guideline as to how to live the happiest possible life, based on the first four of

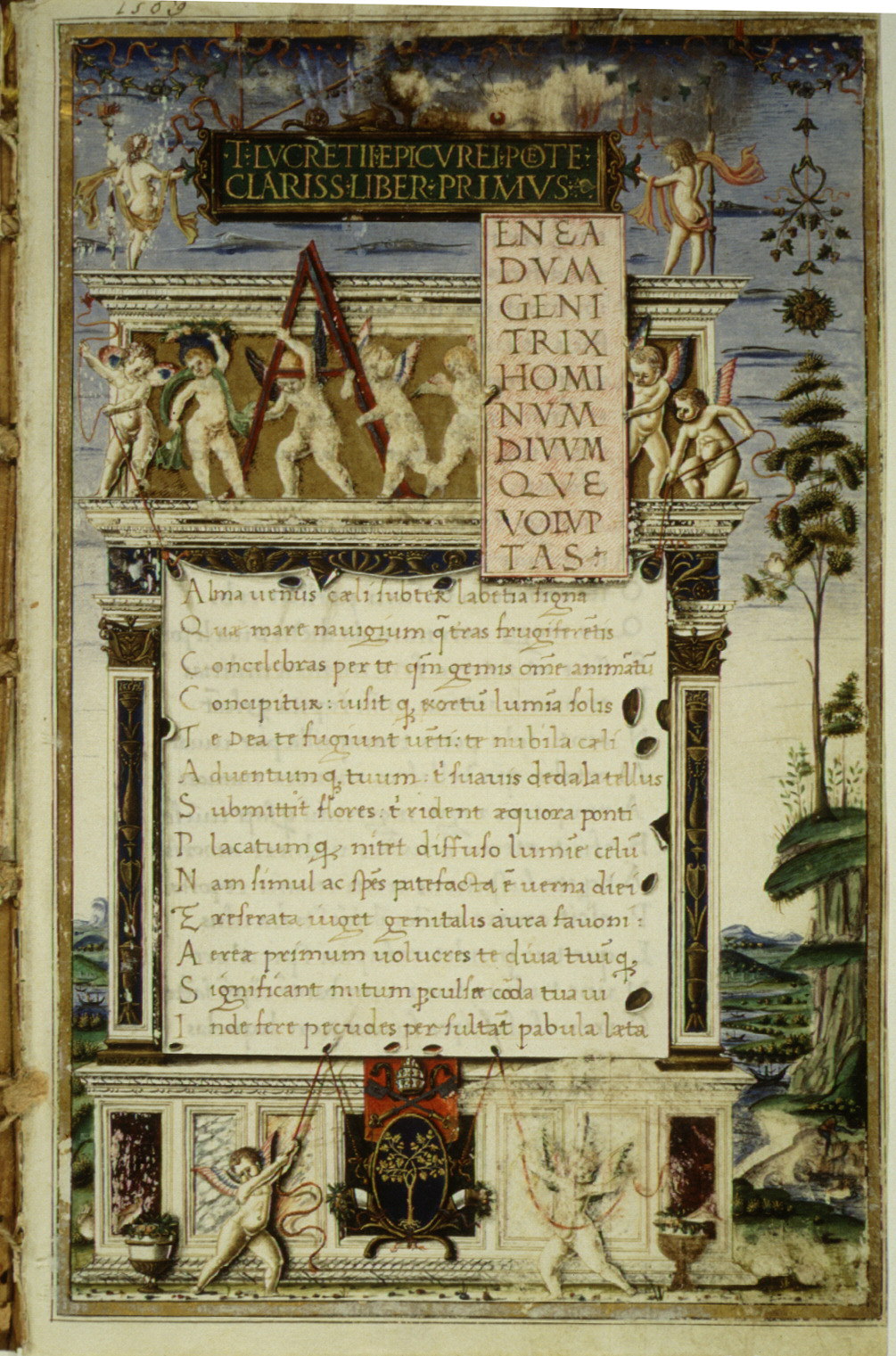

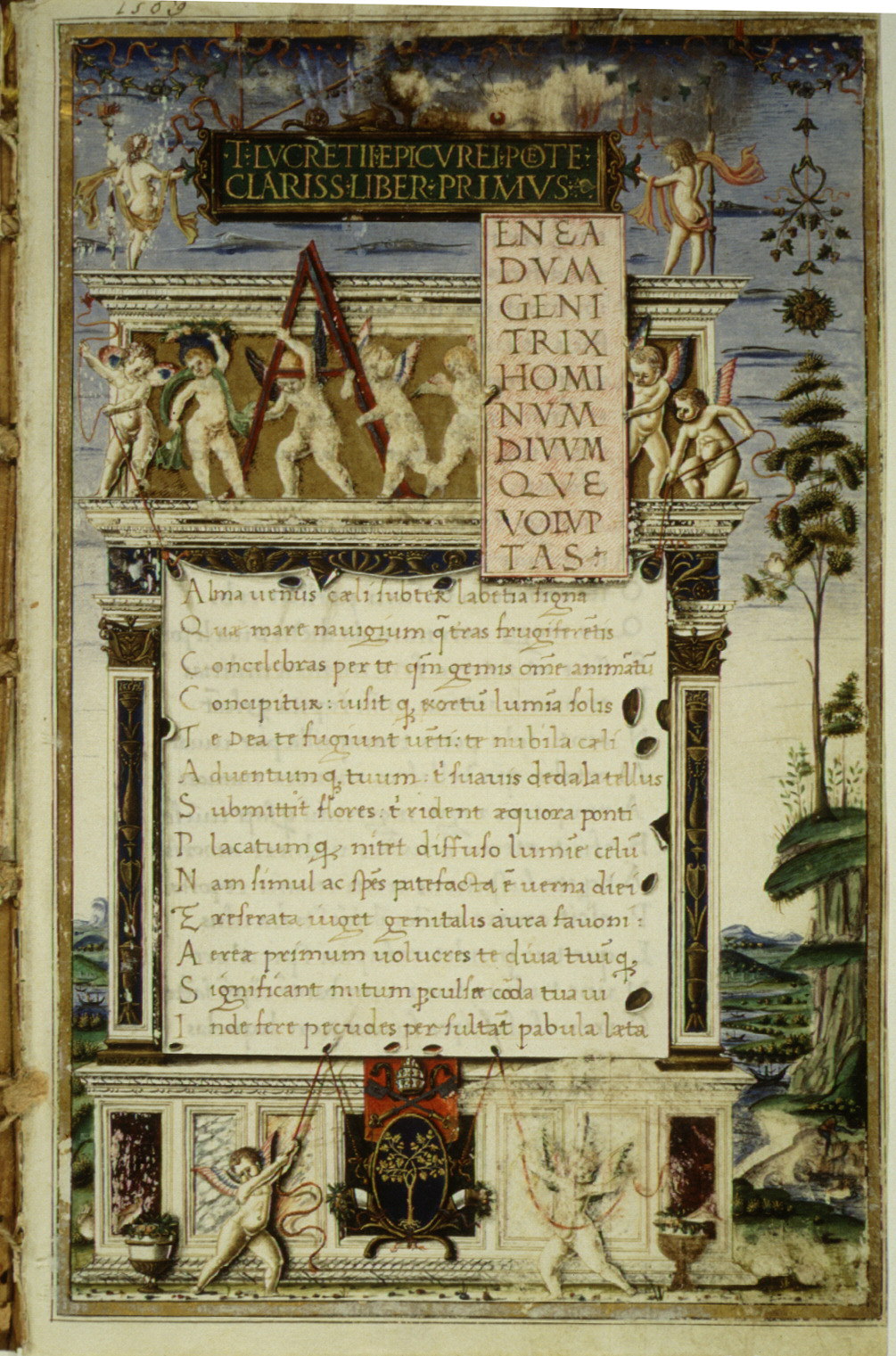

One of the earliest Roman writers espousing Epicureanism was Amafinius. Other adherents to the teachings of Epicurus included the poet

One of the earliest Roman writers espousing Epicureanism was Amafinius. Other adherents to the teachings of Epicurus included the poet

''The Stoics, Epicureans and Sceptics''

Longmans, Green, and Co., 1892 * Vassallo, Christian, ''The Presocratics at Herculaneum: A Study of Early Greek Philosophy in the Epicurean Tradition'', Berlin-Boston: De Gruyter, 2021.

Society of Friends of Epicurus

Epicureans on PhilPapers

Epicurus.info – Epicurean Philosophy Online

Epicurus.net – Epicurus and Epicurean Philosophy

Karl Marx's Notebooks on Epicurean Philosophy

{{Authority control Philosophical schools and traditions Philosophy of life Naturalism (philosophy) Ancient Greek philosophy

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influenced ...

. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century Common Era, BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asser ...

.

Few writings by Epicurus have survived. However, there are independent attestations of his ideas from his later disciples. Some scholars consider the epic poem ''De rerum natura

''De rerum natura'' (; ''On the Nature of Things'') is a first-century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius ( – c. 55 BC) with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some 7 ...

'' (Latin for ''On the Nature of Things'') by Lucretius to present in one unified work the core arguments and theories of Epicureanism. Many of the scrolls unearthed at the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the nea ...

are Epicurean texts. At least some are thought to have belonged to the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus

Philodemus of Gadara ( grc-gre, Φιλόδημος ὁ Γαδαρεύς, ''Philodēmos'', "love of the people"; c. 110 – prob. c. 40 or 35 BC) was an Arabic Epicurean philosopher and poet. He studied under Zeno of Sidon in Athens, before moving ...

. Epicurus also had a wealthy 2nd-century AD disciple, Diogenes of Oenoanda, who had a portico wall inscribed with tenets of the philosophy erected in Oenoanda, Lycia (present day Turkey).

Epicurus was an atomic materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

, following in the steps of Democritus. His materialism led him to a general attack on superstition and divine intervention. Following the Cyrenaic philosopher Aristippus

Aristippus of Cyrene, Libya, Cyrene (; grc, Ἀρίστιππος ὁ Κυρηναῖος; c. 435 – c. 356 BCE) was a Hedonism, hedonistic Ancient Greece, Greek philosopher and the founder of the Cyrenaics, Cyrenaic school of philosophy. He w ...

, Epicurus believed that the greatest good was to seek modest, sustainable pleasure in the form of a state of '' ataraxia'' (tranquility and freedom from fear) and '' aponia'' (the absence of bodily pain) through knowledge of the workings of the world and limiting desires. Correspondingly, Epicurus and his followers generally withdrew from politics because it could lead to frustrations and ambitions, which can directly conflict with the Epicurean pursuit for peace of mind and virtues.

Although Epicureanism is a form of hedonism

Hedonism refers to a family of theories, all of which have in common that pleasure plays a central role in them. ''Psychological'' or ''motivational hedonism'' claims that human behavior is determined by desires to increase pleasure and to decr ...

insofar as it declares pleasure to be its sole intrinsic goal, the concept that the absence of pain and fear constitutes the greatest pleasure, and its advocacy of a simple life, make it very different from "hedonism" as colloquially understood.

Epicureanism flourished in the Late Hellenistic era and during the Roman era, and many Epicurean communities were established, such as those in Antiochia, Alexandria, Rhodes, and Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the nea ...

. By the late 3rd century AD Epicureanism all but died out, being opposed by other philosophies (mainly Neoplatonism) that were now in the ascendant. Interest in Epicureanism was resurrected in the Age of Enlightenment and continues in the modern era.

History

In Mytilene, the capital of the island Lesbos, and then in Lampsacus,Epicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influenced ...

taught and gained followers. In Athens, Epicurus bought a property for his school called "Garden", later the name of Epicurus' school. Its members included Hermarchus, Idomeneus, Colotes, Polyaenus, and Metrodorus. Epicurus emphasized friendship as an important ingredient of happiness, and the school seems to have been a moderately ascetic community which rejected the political limelight of Athenian philosophy. They were fairly cosmopolitan by Athenian standards, including women and slaves. Community activities held some importance, particularly the observance of Eikas

Eikas (Greek εἰκάς from εἴκοσῐ ''eíkosi'', "twenty"), Eikadenfest (also simply referred to as The Twentieth) is a holiday celebrated among Epicureans in commemoration of Epicurus and Metrodorus. It is a monthly celebration taking pl ...

, a monthly social gathering. Some members were also vegetarians as, from slender evidence, Epicurus did not eat meat, although no prohibition against eating meat was made.

The school's popularity grew and it became, along with Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century Common Era, BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asser ...

, Platonism, Peripateticism, and Pyrrhonism

Pyrrhonism is a school of philosophical skepticism founded by Pyrrho in the fourth century BCE. It is best known through the surviving works of Sextus Empiricus, writing in the late second century or early third century CE.

History

Pyrrho of E ...

, one of the dominant schools of Hellenistic philosophy

Hellenistic philosophy is a time-frame for Western philosophy and Ancient Greek philosophy corresponding to the Hellenistic period. It is purely external and encompasses disparate intellectual content. There is no single philosophical school or cu ...

, lasting strongly through the later Roman Empire. Another major source of information is the Roman politician and philosopher Cicero, although he was highly critical, denouncing the Epicureans as unbridled hedonists, devoid of a sense of virtue and duty, and guilty of withdrawing from public life. Another ancient source is Diogenes of Oenoanda, who composed a large inscription at Oenoanda in Lycia.

Deciphered carbonized scroll

A scroll (from the Old French ''escroe'' or ''escroue''), also known as a roll, is a roll of papyrus, parchment, or paper containing writing.

Structure

A scroll is usually partitioned into pages, which are sometimes separate sheets of papyrus ...

s obtained from the library at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the nea ...

contain a large number of works by Philodemus

Philodemus of Gadara ( grc-gre, Φιλόδημος ὁ Γαδαρεύς, ''Philodēmos'', "love of the people"; c. 110 – prob. c. 40 or 35 BC) was an Arabic Epicurean philosopher and poet. He studied under Zeno of Sidon in Athens, before moving ...

, a late Hellenistic Epicurean, and Epicurus himself, attesting to the school's enduring popularity. Diogenes reports slanderous stories, circulated by Epicurus' opponents. With growing dominance of Neoplatonism and Peripateticism, and later, Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

, Epicureanism declined. By the late third century AD, there was little trace of its existence. The early Christian writer Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor, Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Cr ...

criticizes Epicurus at several points throughout his ''Divine Institutes''. In Dante Alighieri's '' Divine Comedy'', the Epicureans are depicted as heretics suffering in the sixth circle of hell. In fact, Epicurus appears to represent the ultimate heresy.

In the 17th century, the French Franciscan priest, scientist and philosopher Pierre Gassendi wrote two books forcefully reviving Epicureanism. Shortly thereafter, and clearly influenced by Gassendi, Walter Charleton published several works on Epicureanism in English. Attacks by Christians continued, most forcefully by the Cambridge Platonists.

Philosophy

Epicureanism argued thatpleasure

Pleasure refers to experience that feels good, that involves the enjoyment of something. It contrasts with pain or suffering, which are forms of feeling bad. It is closely related to value, desire and action: humans and other conscious anima ...

was the chief good in life. Hence, Epicurus advocated living in such a way as to derive the greatest amount of pleasure possible during one's lifetime, yet doing so moderately in order to avoid the suffering incurred by overindulgence in such pleasure. Emphasis was placed on pleasures of the mind rather than on physical pleasures. Unnecessary and, especially, artificially produced desires were to be suppressed. Since the political life could give rise to desires that could disturb virtue and one's peace of mind, such as a lust for power or a desire for fame, participation in politics was discouraged. Further, Epicurus sought to eliminate the fear of the gods and of death, seeing those two fears as chief causes of strife in life. Epicurus actively recommended against passionate love, and believed it best to avoid marriage altogether. He viewed recreational sex as a natural, but not necessary, desire that should be generally avoided.

The Epicurean understanding of justice was inherently self-interested. Justice was deemed good because it was seen as mutually beneficial. Individuals would not act unjustly even if the act was initially unnoticed because of possibly being caught and punished. Both punishment and fear of punishment would cause a person disturbance and prevent them from being happy.

Epicurus laid great emphasis on developing friendships as the basis of a satisfying life.

While the pursuit of pleasure formed the focal point of the philosophy, this was largely directed to the "static pleasures" of minimizing pain, anxiety and suffering.

Epicureanism rejects immortality. It believes in the soul, but suggests that the soul is mortal and material, just like the body. Epicurus rejected any possibility of an afterlife, while still contending that one need not fear death: "Death is nothing to us; for that which is dissolved, is without sensation, and that which lacks sensation is nothing to us." From this doctrine arose the Epicurean Epitaph: ''Non fui, fui, non sum, non curo'' ("I was not; I have been; I am not; I do not mind."), which is inscribed on the gravestones of his followers and seen on many ancient gravestones of the Roman Empire. This quotation is often used today at humanist funerals.

Ethics

Epicureanism bases its ethics on a hedonistic set of values. In the most basic sense, Epicureans see pleasure as the purpose of life. As evidence for this, Epicureans say that nature seems to command us to avoid pain, and they point out that all animals try to avoid pain as much as possible. Epicureans had a very specific understanding of what the greatest pleasure was, and the focus of their ethics was on the avoidance of pain rather than seeking out pleasure. Epicureanism divided pleasure into two broad categories: ''pleasures of the body'' and ''pleasures of the mind''. *''Pleasures of the body'': These pleasures involve sensations of the body, such as the act of eating delicious food or of being in a state of comfort free from pain, and exist only in the present. One can only experience pleasures of the body in the moment, meaning they only exist as a person is experiencing them. *''Pleasures of the mind'': These pleasures involve mental processes and states; feelings of joy, the lack of fear, and pleasant memories are all examples of pleasures of the mind. These pleasures of the mind do not only exist in the present, but also in the past and future, since memory of a past pleasant experience or the expectation of some potentially pleasing future can both be pleasurable experiences. Because of this, the pleasures of the mind are considered to be greater than those of the body. The Epicureans further divided each of these types of pleasures into two categories: ''kinetic pleasure'' and '' katastematic pleasure''. *''Kinetic pleasure'': Kinetic pleasure describes the physical or mental pleasures that involve action or change. Eating delicious food, as well as fulfilling desires and removing pain, which is itself considered a pleasurable act, are all examples of kinetic pleasure in the physical sense. According to Epicurus, feelings of joy would be an example of mental kinetic pleasure. *''Katastematic pleasure'': Katastematic pleasure describes the pleasure one feels while in a state without pain. Like kinetic pleasures, katastematic pleasures can also be physical, such as the state of not being thirsty, or mental, such as freedom from a state of fear. Complete physical katastematic pleasure is called '' aponia'', and complete mental katastematic pleasure is called '' ataraxia''. From this understanding, Epicureans concluded that the greatest pleasure a person could reach was the complete removal of all pain, both physical and mental. The ultimate goal then of Epicurean ethics was to reach a state of ''aponia'' and ''ataraxia''. In order to do this an Epicurean had to control their desires, because desire itself was seen as painful. Not only will controlling one's desires bring about ''aponia'', as one will rarely suffer from not being physically satisfied, but controlling one's desires will also help to bring about ''ataraxia'' because one will not be anxious about becoming discomforted since one would have so few desires anyway. The Epicureans divide desires into three classes: natural and necessary, natural but not necessary, and vain and empty. *''Natural and necessary'': These desires are limited desires that are innately present in all humans; it is part of human nature to have them. They are necessary for one of three reasons: necessary for happiness, necessary for freedom from bodily discomfort, and necessary for life. Clothing and shelter would belong to the first two categories, while something like food would belong to the third. *''Natural but not necessary'': These desires are innate to humans, but they do not need to be fulfilled for their happiness or their survival. Wanting to eat delicious food when one is hungry is an example of a natural but not necessary desire. The main problem with these desires is that they fail to substantially increase a person's happiness, and at the same time require effort to obtain and are desired by people due to false beliefs that they are actually necessary. It is for this reason that they should be avoided. *''Vain and empty'': These desires are neither innate to humans nor required for happiness or health; indeed, they are also limitless and can never be fulfilled. Desires of wealth or fame would fall in this class, and such desires are to be avoided because they will ultimately only bring about discomfort. If one follows only natural and necessary desires, then, according to Epicurus, one would be able to reach ''aponia'' and ''ataraxia'' and thereby the highest form of happiness. Epicurus was also an early thinker to develop the notion of justice as asocial contract

In moral and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships betw ...

. He defined justice as an agreement made by people not to harm each other. The point of living in a society with laws and punishments is to be protected from harm so that one is free to pursue happiness. Because of this, laws that do not contribute to promoting human happiness are not just. He gave his own unique version of the ethic of reciprocity, which differs from other formulations by emphasizing minimizing harm and maximizing happiness for oneself and others:

("Justly" here means to prevent a "person from harming or being harmed by another".)

Epicureanism incorporated a relatively full account of the social contract theory, and in part attempts to address issues with the society described in Plato's ''Republic''. The social contract theory established by Epicureanism is based on mutual agreement, not divine decree.

Politics

Epicurean ideas on politics disagree with other philosophical traditions, namely the Stoic, Platonist and Aristotelian traditions. To Epicureans all our social relations are a matter of how we perceive each other, of customs and traditions. No one is inherently of higher value or meant to dominate another. That is because there is no metaphysical basis for the superiority of one kind of person, all people are made of the same atomic material and are thus naturally equal. Epicureans also discourage political participation and other involvement in politics. However Epicureans are not apolitical, it is possible that some political association could be seen as beneficial by some Epicureans. Some political associations could lead to certain benefits to the individual that would help to maximize pleasure and avoid physical or mental distress. The avoidance or freedom from hardship and fear is ideal to the Epicureans. While this avoidance or freedom could conceivably be achieved through political means it was insisted by Epicurus that involvement in politics would not release one from fear and he advised against a life of politics. Epicurus also discouraged contributing to political society by starting a family, as the benefits of a wife and children are outweighed by the trouble brought about by having a family. Instead Epicurus encouraged a formation of a community of friends outside the traditional political state. This community of virtuous friends would focus on internal affairs and justice. However, Epicureanism is adaptable to circumstance as is the Epicurean approach to politics. The same approaches will not always work in protection from pain and fear. In some situations it will be more beneficial to have a family and in other situations it will be more beneficial to participate in politics. It is ultimately up to the Epicurean to analyse their circumstance and take whatever action befits the situation.Religion

Epicureanism does not deny the existence of the gods; rather it denies their involvement in the world. According to Epicureanism, the gods do not interfere with human lives or the rest of the universe in any way – thus, it shuns the idea that frightening weather events are divine retribution. One of the fears the Epicurean ought to be freed from is fear relating to the actions of the gods. The manner in which the Epicurean gods exist is still disputed. Some scholars say that Epicureanism believes that the gods exist outside the mind as material objects (the realist position), while others assert that the gods only exist in our minds as ideals (the idealist position). The realist position holds that Epicureans understand the gods as existing as physical and immortal beings made of atoms that reside somewhere in reality. However, the gods are completely separate from the rest of reality; they are uninterested in it, play no role in it, and remain completely undisturbed by it. Instead, the gods live in what is called the ''metakosmia

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the Hellenistic philosophy, ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoici ...

'', or the space between worlds. Contrarily, the idealist (sometimes called the “non-realist position” to avoid confusion) position holds that the gods are just idealized forms of the best human life, and it is thought that the gods were emblematic of the life one should aspire towards. The debate between these two positions was revived by A. A. Long and David Sedley in their 1987 book, ''The Hellenistic Philosophers'', in which the two argued in favour of the idealist position. While a scholarly consensus has yet to be reached, the realist position remains the prevailing viewpoint at this time.

Epicureanism also offered arguments against the existence of the gods in the manner proposed by other belief systems. The ''Riddle of Epicurus'', or '' Problem of evil'', is a famous argument against the existence of an all-powerful and providential God or gods. As recorded by Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor, Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Cr ...

:

This type of '' trilemma'' argument (God is omnipotent, God is good, but Evil exists) was one favoured by the ancient Greek skeptics, and this argument may have been wrongly attributed to Epicurus by Lactantius, who, from his Christian perspective, regarded Epicurus as an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

.Mark Joseph Larrimore, (2001), ''The Problem of Evil'', pp. xix–xxi. Wiley-Blackwell According to Reinhold F. Glei

Reinhold F. Glei (; born 11 June 1959 in Remscheid) is a German philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguisti ...

, it is settled that the argument of theodicy is from an academical source which is not only not Epicurean, but even anti-Epicurean. The earliest extant version of this ''trilemma'' appears in the writings of the Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, ; ) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Pyrrhonism, Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and ...

.

Parallels may be drawn to Jainism and Buddhism, which similarly emphasize a lack of divine interference and aspects of its atomism. Epicureanism also resembles Buddhism in its temperateness, including the belief that great excess leads to great dissatisfaction.Dee L. Clayman (2014)''Berenice II and the Golden Age of Ptolemaic Egypt''

Oxford University Press, p.33 Some modern Epicureans have argued that Epicureanism is a type of religious identity, arguing that it fulfils Ninian Smart's "seven dimensions of religion", and that the Epicurean practices of feasting on the twentieth and declaring an oath to follow Epicurus, insistence on doctrinal adherence, and the sacredness of Epicurean friendship, make Epicureanism more similar to some non-theistic religions than to other philosophies.

Epicurean physics

Epicurean physics held that the entire universe consisted of two things: matter and void. Matter is made up of atoms, which are tiny bodies that have only the unchanging qualities of shape, size, and weight. Atoms were felt to be unchanging because the Epicureans believed that the world was ordered and that changes had to have specific and consistent sources, e.g. a plant species only grows from a seed of the same species. Epicurus holds that there must be an infinite supply of atoms, although only a finite number of types of atoms, as well as an infinite amount of void. Epicurus explains this position in his letter to Herodotus:Moreover, the sum of things is unlimited both by reason of the multitude of the atoms and the extent of the void. For if the void were infinite and bodies finite, the bodies would not have stayed anywhere but would have been dispersed in their course through the infinite void, not having any supports or counterchecks to send them back on their upward rebound. Again, if the void were finite, the infinity of bodies would not have anywhere to be.Because of the infinite supply of atoms, there are an infinite amount of worlds, or ''cosmoi''. Some of these worlds could be vastly different than our own, some quite similar, and all of the worlds were separated from each other by vast areas of void (''

metakosmia

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the Hellenistic philosophy, ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoici ...

'').

Epicureanism states that atoms are unable to be broken down into any smaller parts, and Epicureans offered multiple arguments to support this position. Epicureans argue that because void is necessary for matter to move, anything which consists of both void and matter can be broken down, while if something contains no void then it has no way to break apart because no part of the substance could be broken down into a smaller subsection of the substance. They also argued that in order for the universe to persist, what it is ultimately made up of must not be able to be changed or else the universe would be essentially destroyed.

Atoms are constantly moving in one of four different ways. Atoms can simply collide with each other and then bounce off of each other. When joined with each other and forming a larger object, atoms can vibrate as they collide into each other while still maintaining the overall shape of the larger object. When not prevented by other atoms, all atoms move at the same speed naturally downwards in relation to the rest of the world. This downwards motion is natural for atoms; however, as their fourth means of motion, atoms can at times randomly swerve out of their usual downwards path. This swerving motion is what allowed for the creation of the universe, since as more and more atoms swerved and collided with each other, objects were able to take shape as the atoms joined together. Without the swerve, the atoms would never have interacted with each other, and simply continued to move downwards at the same speed.

Epicurus also felt that the swerve was what accounted for humanity's free will. If it were not for the swerve, humans would be subject to a never-ending chain of cause and effect. This was a point which Epicureans often used to criticize Democritus' atomic theory.

Epicureans believed that senses also relied on atoms. Every object was continually emitting particles from itself that would then interact with the observer. All sensations, such as sight, smell, or sound, relied on these particles. While the atoms that were emitted did not have the qualities that the senses were perceiving, the manner in which they were emitted caused the observer to experience those sensations, e.g. red particles were not themselves red but were emitted in a manner that caused the viewer to experience the color red. The atoms are not perceived individually, but rather as a continuous sensation because of how quickly they move.

Epistemology

Epicurean philosophy employs anempirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

epistemology. The Epicureans believed that all sense perceptions were true, and that errors arise in how we judge those perceptions. When we form judgments about things (''hupolepsis''), they can be verified and corrected through further sensory information. For example, if someone sees a tower from far away that appears to be round, and upon approaching the tower they see that it is actually square, they would come to realize that their original judgement was wrong and correct their wrong opinion.

Epicurus is said to have proposed three criteria of truth: sensations (''aisthêsis''), preconceptions (''prolepsis''), and feelings (''pathê''). A fourth criterion called "presentational applications of the mind" (''phantastikai epibolai tês dianoias'') was said to have been added by later Epicureans. These criteria formed the method through which Epicureans thought we gained knowledge.

Since Epicureans thought that sensations could not deceive, sensations are the first and main criterion of truth for Epicureans. Even in cases where sensory input seems to mislead, the input itself is true and the error arises from our judgments about the input. For example, when one places a straight oar in the water, it appears bent. The Epicurean would argue that image of the oar, that is the atoms travelling from the oar to the observer's eyes, have been shifted and thus really do arrive at the observer's eyes in the shape of a bent oar. The observer makes the error in assuming that the image he or she receives correctly represents the oar and has not been distorted in some way. In order to not make erroneous judgments about perceivable things and instead verify one's judgment, Epicureans believed that one needed to obtain "clear vision" (''enargeia'') of the perceivable thing by closer examination. This acted as a justification for one's judgements about the thing being perceived. ''Enargeia'' is characterized as sensation of an object that has been unchanged by judgments or opinions and is a clear and direct perception of that object.

An individual's preconceptions are his or her concepts of what things are, e.g. what someone's idea of a horse is, and these concepts are formed in a person's mind through sensory input over time. When the word that relates to the preconception is used, these preconceptions are summoned up by the mind into the person's thoughts. It is through our preconceptions that we are able to make judgments about the things that we perceive. Preconceptions were also used by Epicureans to avoid the paradox proposed by Plato in the '' Meno'' regarding learning. Plato argues that learning requires us to already have knowledge of what we are learning, or else we would be unable to recognize when we had successfully learned the information. Preconceptions, Epicureans argue, provide individuals with that pre-knowledge required for learning.

Our feelings or emotions (''pathê'') are how we perceive pleasure and pain. They are analogous to sensations in that they are a means of perception, but they perceive our internal state as opposed to external things. According to Diogenes Laertius, feelings are how we determine our actions. If something is pleasurable, we pursue that thing, and if something is painful, we avoid that thing.

The idea of "presentational applications of the mind" is an explanation for how we can discuss and inquire about things we cannot directly perceive. We receive impressions of such things directly in our minds, instead of perceiving them through other senses. The concept of "presentational applications of the mind" may have been introduced to explain how we learn about things that we cannot directly perceive, such as the gods.

Tetrapharmakos

Tetrapharmakos, or "The four-part cure", is Philodemus of Gadara's basic guideline as to how to live the happiest possible life, based on the first four of

Tetrapharmakos, or "The four-part cure", is Philodemus of Gadara's basic guideline as to how to live the happiest possible life, based on the first four of Epicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influenced ...

' Principal Doctrines

The Principal Doctrines are forty authoritative conclusions set up as official doctrines by the founders of Epicureanism: Epicurus of Samos, Metrodorus of Lampsacus, Hermarchus of Mitilene and Polyaenus of Lampsacus. The first four doctrines make ...

. This poetic doctrine was handed down by an anonymous Epicurean who summed up Epicurus' philosophy on happiness in four simple lines:

Notable Epicureans

One of the earliest Roman writers espousing Epicureanism was Amafinius. Other adherents to the teachings of Epicurus included the poet

One of the earliest Roman writers espousing Epicureanism was Amafinius. Other adherents to the teachings of Epicurus included the poet Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

, whose famous statement ''Carpe Diem'' ("Seize the Day") illustrates the philosophy, as well as Lucretius, who wrote the poem ''De rerum natura'' about the tenets of the philosophy. The poet Virgil was another prominent Epicurean (see Lucretius for further details). The Epicurean philosopher Philodemus of Gadara, until the 18th century only known as a poet of minor importance, rose to prominence as most of his work along with other Epicurean material was discovered in the Villa of the Papyri. In the 2nd century AD, comedian Lucian of Samosata and wealthy promoter of philosophy Diogenes of Oenoanda were prominent Epicureans.

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

leaned considerably toward Epicureanism, which led to his plea against the death sentence during the trial against Catiline, during the Catiline conspiracy

The Catilinarian conspiracy (sometimes Second Catilinarian conspiracy) was an attempted coup d'état by Lucius Sergius Catilina (Catiline) to overthrow the Roman consuls of 63 BC – Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida – an ...

where he spoke out against the Stoic Cato. His father-in-law, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, was also an adept of the school.

In modern times Thomas Jefferson referred to himself as an Epicurean:If I had time I would add to my little book the Greek, Latin and French texts, in columns side by side. And I wish I could subjoin a translation of Gassendi's Syntagma of the doctrines of Epicurus, which, notwithstanding the calumnies of the Stoics and caricatures of Cicero, is the most rational system remaining of the philosophy of the ancients, as frugal of vicious indulgence, and fruitful of virtue as the hyperbolical extravagances of his rival sects.Other modern-day Epicureans were Gassendi, Walter Charleton, François Bernier, Saint-Évremond,

Ninon de l'Enclos

Anne "Ninon" de l'Enclos, also spelled Ninon de Lenclos and Ninon de Lanclos (10 November 1620 – 17 October 1705), was a French author, courtesan and patron of the arts.

Early life

Born Anne de l'Enclos in Paris on 10 November 1620,Sources als ...

, Denis Diderot, Frances Wright and Jeremy Bentham.

In France, where perfumer/restaurateur Gérald Ghislain refers to himself as an Epicurean, Michel Onfray is developing a post-modern approach to Epicureanism. In his recent book titled '' The Swerve'', Stephen Greenblatt

Stephen Jay Greenblatt (born November 7, 1943) is an American Shakespearean, literary historian, and author. He has served as the John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University since 2000. Greenblatt is the general edit ...

identified himself as strongly sympathetic to Epicureanism and Lucretius. Humanistic Judaism

Humanistic Judaism ( ''Yahadut Humanistit'') is a Jewish movement that offers a nontheistic alternative to contemporary branches of Judaism. It defines Judaism as the cultural and historical experience of the Jewish people rather than a religio ...

as a denomination also claims the Epicurean label.

Modern usage and misconceptions

In modern popular usage, an Epicurean is a connoisseur of the arts of life and the refinements of sensual pleasures; ''Epicureanism'' implies a love or knowledgeable enjoyment especially of good food and drink. Because Epicureanism posits that pleasure is the ultimate good (''telos''), it has been commonly misunderstood since ancient times as a doctrine that advocates the partaking in fleeting pleasures such as sexual excess and decadent food. This is not the case. Epicurus regarded '' ataraxia'' (tranquility, freedom from fear) and '' aponia'' (absence of pain) as the height of happiness. He also considered prudence an important virtue and perceived excess and overindulgence to be contrary to the attainment of ataraxia and aponia. Epicurus preferred "the good", and "even wisdom and culture", to the "pleasure of the stomach". While 20th-century commentary has generally sought to diminish this and related quotations, the consistency of the lower-case epicureanism of meals with Epicurean materialism overall has more recently been explained. While Epicurus sought moderation at meals, he was also not averse to moderation in moderation, that is, to occasional luxury. Called "The Garden" for being based in what would have been a kitchen garden, his community also became known for its feasts of the twentieth (of the Greek month).Criticism

Francis Bacon wrote an apothegm related to Epicureanism:There was an Epicurean vaunted, that divers of other sects of philosophers did after turn Epicureans, but there was never any Epicurean that turned to any other sect. Whereupon a philosopher that was of another sect, said; The reason was plain, for that cocks may be made capons, but capons could never be made cocks.This echoed what the Academic skeptic philosopher Arcesilaus had said when asked "why it was that pupils from all the other schools went over to Epicurus, but converts were never made from the Epicureans?" to which he responded: "Because men may become eunuchs, but a eunuch never becomes a man." Diogenes Laertius, '' Lives of the Eminent Philosophers'' Book IV, Chapter 6, section 45 http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0258%3Abook%3D4%3Achapter%3D6

See also

*Charvaka

Charvaka ( sa, चार्वाक; IAST: ''Cārvāka''), also known as ''Lokāyata'', is an ancient school of Indian materialism. Charvaka holds direct perception, empiricism, and conditional inference as proper sources of knowledge, embrac ...

, a hedonic Indian school

* Cyrenaics, a sensual hedonist Greek school of philosophy founded in the 4th century BC

* '' Epicurea''

* Epikoros

* Hedonic treadmill

The hedonic treadmill, also known as hedonic adaptation, is the observed tendency of humans to quickly return to a relatively stable level of happiness despite major positive or negative events or life changes.

According to this theory, as a per ...

* List of English translations of ''De rerum natura''

* Philosophy of happiness

* Roman decadence

* Separation of church and state

* Zeno of Sidon

References

Further reading

* Dane R. Gordon and David B. Suits, ''Epicurus. His Continuing Influence and Contemporary Relevance'', Rochester, N.Y.: RIT Cary Graphic Arts Press, 2003. * Holmes, Brooke & Shearin, W. H. ''Dynamic Reading: Studies in the Reception of Epicureanism'', New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. * Jones, Howard. ''The Epicurean Tradition'', New York: Routledge, 1989. * Neven Leddy and Avi S. Lifschitz, ''Epicurus in the Enlightenment'', Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2009. * Long, A.A. & Sedley, D.N. The Hellenistic Philosophers Volume 1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987. () * * Martin Ferguson Smith (ed.), ''Diogenes of Oinoanda. The Epicurean inscription'', edited with introduction, translation, and notes, Naples: Bibliopolis, 1993. * Martin Ferguson Smith, ''Supplement to Diogenes of Oinoanda. The Epicurean Inscription'', Naples: Bibliopolis, 2003. * Warren, James (ed.) ''The Cambridge Companion to Epicureanism'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. * Wilson, Catherine. ''Epicureanism at the Origins of Modernity'', New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. * Zeller, Eduard; Reichel, Oswald J.''The Stoics, Epicureans and Sceptics''

Longmans, Green, and Co., 1892 * Vassallo, Christian, ''The Presocratics at Herculaneum: A Study of Early Greek Philosophy in the Epicurean Tradition'', Berlin-Boston: De Gruyter, 2021.

External links

Society of Friends of Epicurus

Epicureans on PhilPapers

Epicurus.info – Epicurean Philosophy Online

Epicurus.net – Epicurus and Epicurean Philosophy

Karl Marx's Notebooks on Epicurean Philosophy

{{Authority control Philosophical schools and traditions Philosophy of life Naturalism (philosophy) Ancient Greek philosophy