Emperor Ferdinand I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ferdinand I ( es, Fernando I; 10 March 1503 – 25 July 1564) was

The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001. Ferdinand also served as his brother's deputy in the Holy Roman Empire during his brother's many absences, and in 1531 was elected

According to the terms set at the First Congress of Vienna in 1515, Ferdinand married Anne Jagiellonica, daughter of King Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary on 22 July 1515. Both Hungary and Bohemia were

According to the terms set at the First Congress of Vienna in 1515, Ferdinand married Anne Jagiellonica, daughter of King Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary on 22 July 1515. Both Hungary and Bohemia were  In 1538, in the Treaty of Nagyvárad, Ferdinand induced the childless Zápolya to name him as his successor. But in 1540, just before his death, Zápolya had a son,

In 1538, in the Treaty of Nagyvárad, Ferdinand induced the childless Zápolya to name him as his successor. But in 1540, just before his death, Zápolya had a son,

entry in the

After 1555, the Peace of Augsburg became the legitimating legal document governing the co-existence of the Lutheran and Catholic faiths in the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, and it served to ameliorate many of the tensions between followers of the "Old Faith" (

After 1555, the Peace of Augsburg became the legitimating legal document governing the co-existence of the Lutheran and Catholic faiths in the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, and it served to ameliorate many of the tensions between followers of the "Old Faith" (

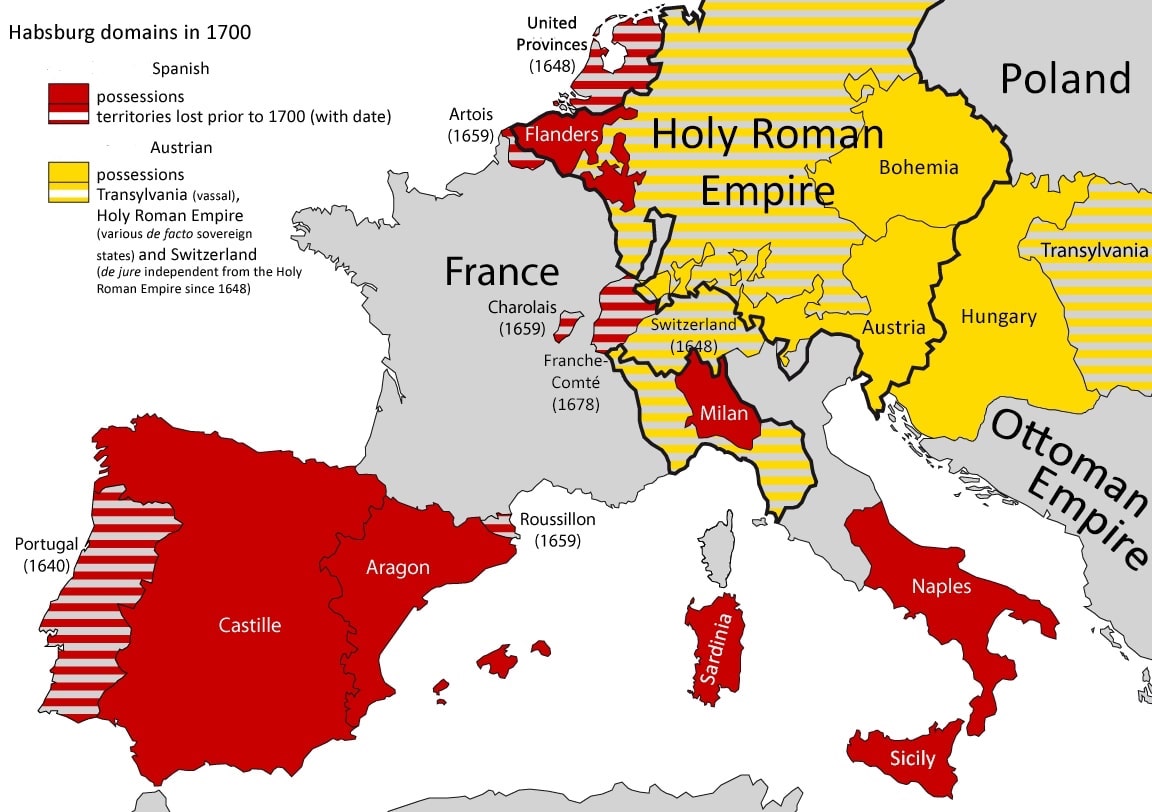

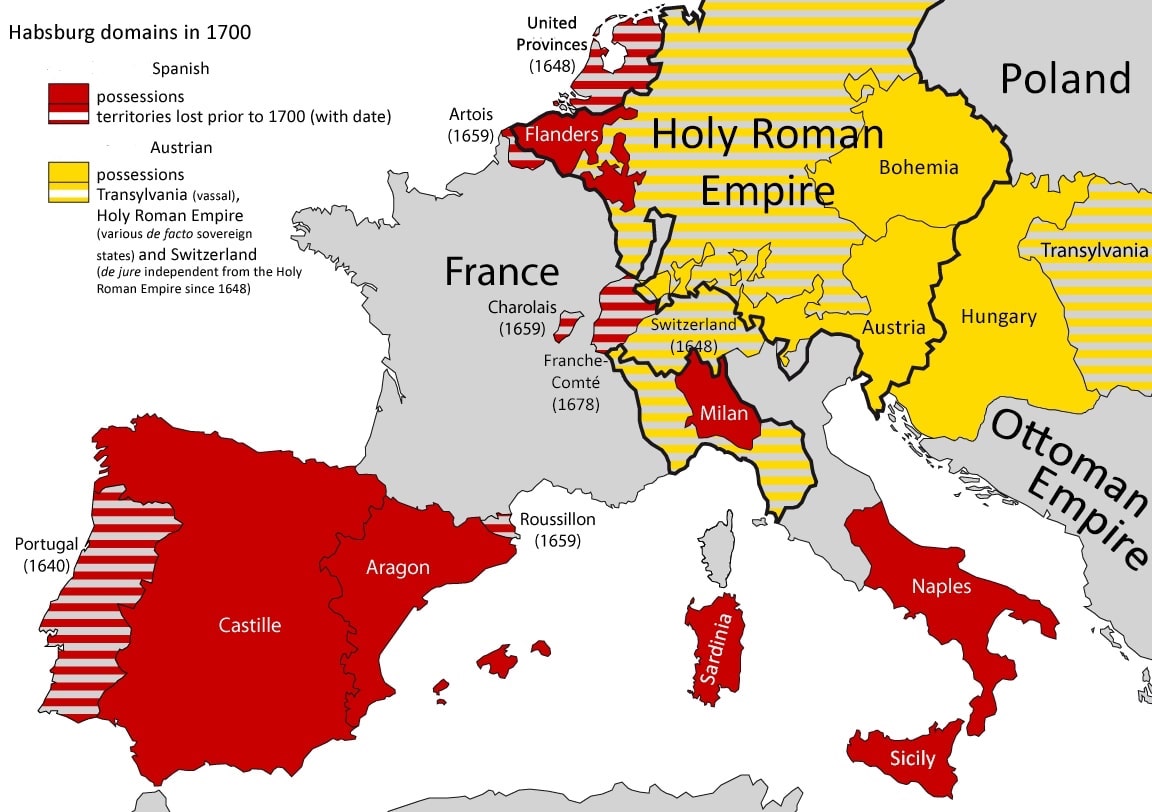

Charles's choices were appropriate. Philip was culturally Spanish: he was born in

Charles's choices were appropriate. Philip was culturally Spanish: he was born in

Charles abdicated as Emperor in August 1556 in favor of his brother Ferdinand. Given the settlement of 1521 and the election of 1531, Ferdinand became Holy Roman Emperor and '' suo jure'' Archduke of Austria. Due to lengthy debate and bureaucratic procedure, the Imperial Diet did not accept the Imperial succession until 3 May 1558. The Pope refused to recognize Ferdinand as Emperor until 1559, when peace was reached between France and the Habsburgs. During his Emperorship, the

Charles abdicated as Emperor in August 1556 in favor of his brother Ferdinand. Given the settlement of 1521 and the election of 1531, Ferdinand became Holy Roman Emperor and '' suo jure'' Archduke of Austria. Due to lengthy debate and bureaucratic procedure, the Imperial Diet did not accept the Imperial succession until 3 May 1558. The Pope refused to recognize Ferdinand as Emperor until 1559, when peace was reached between France and the Habsburgs. During his Emperorship, the

Since 1542, Charles V and Ferdinand had been able to collect the Common Penny tax, or ''Türkenhilfe'' (Turkish aid), designed to protect the Empire against the Ottomans or France. But as Hungary, unlike Bohemia, was not part of the Reich, the imperial aid for Hungary depended on political factors. The obligation was only in effect if Vienna or the Empire was threatened.

The western part of Hungary over which Ferdinand had dominion became known as

Since 1542, Charles V and Ferdinand had been able to collect the Common Penny tax, or ''Türkenhilfe'' (Turkish aid), designed to protect the Empire against the Ottomans or France. But as Hungary, unlike Bohemia, was not part of the Reich, the imperial aid for Hungary depended on political factors. The obligation was only in effect if Vienna or the Empire was threatened.

The western part of Hungary over which Ferdinand had dominion became known as

In December 1562, Ferdinand had Maximilian, his eldest son elected King of the Romans. This was followed with succession in Bohemia, and in 1563, the crown of Hungary.

Ferdinand died in

In December 1562, Ferdinand had Maximilian, his eldest son elected King of the Romans. This was followed with succession in Bohemia, and in 1563, the crown of Hungary.

Ferdinand died in

Ferdinand's legacy ultimately proved enduring. Though lacking resources, he managed to defend his land against the Ottomans with limited support from his brother, and even secured a part of Hungary that would later provide the basis for the conquest of the whole kingdom by the Habsburgs. In his own possessions, he built a tax system that, though imperfect, would continue to be used by his successors. His handling of the Protestant Reformation proved more flexible and more effective than that of his brother and he played a key part in the settlement of 1555, which started an era of peace in Germany. His statesmanship, overall, was cautious and effective. On the other hand, when he engaged in more audacious endeavours, like his offensives against Buda and Pest, it often ended in failure.

Fichtner remarks that Ferdinand was a mediocre military commander (thus the many difficulties in dealing with the Ottomans in Hungary) but an energetic and very imaginative administrator, who produced a framework for his empire that would endured into the eighteenth century. The core included a court council, privy council, central treasury and a body for military affairs, with the written business conducted by a common chancery. In his time and in practice, Bohemia and Hungary resisted cooperating with the structure but the German territories widely imitated it.

Ferdinand was also a patron of the arts. He embellished Vienna and Prague. The

Ferdinand's legacy ultimately proved enduring. Though lacking resources, he managed to defend his land against the Ottomans with limited support from his brother, and even secured a part of Hungary that would later provide the basis for the conquest of the whole kingdom by the Habsburgs. In his own possessions, he built a tax system that, though imperfect, would continue to be used by his successors. His handling of the Protestant Reformation proved more flexible and more effective than that of his brother and he played a key part in the settlement of 1555, which started an era of peace in Germany. His statesmanship, overall, was cautious and effective. On the other hand, when he engaged in more audacious endeavours, like his offensives against Buda and Pest, it often ended in failure.

Fichtner remarks that Ferdinand was a mediocre military commander (thus the many difficulties in dealing with the Ottomans in Hungary) but an energetic and very imaginative administrator, who produced a framework for his empire that would endured into the eighteenth century. The core included a court council, privy council, central treasury and a body for military affairs, with the written business conducted by a common chancery. In his time and in practice, Bohemia and Hungary resisted cooperating with the structure but the German territories widely imitated it.

Ferdinand was also a patron of the arts. He embellished Vienna and Prague. The

A pedigree of the Habsburg

* *

Biography of the website of the ''Residenzen-Kommission''

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Ferdinand 1, Holy Roman Emperor 1503 births 1564 deaths 16th-century Holy Roman Emperors 16th-century archdukes of Austria Burials at St. Vitus Cathedral Knights of the Garter Knights of the Golden Fleece Spanish infantes Aragonese infantes Castilian infantes Nobility from Madrid People from Alcalá de Henares 16th-century Spanish people Dukes of Carniola

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

from 1556, King of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia was established in 870 and raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1198. Several Bohemian monarchs ruled as non-hereditary kings beforehand, first gaining the title in 1085. From 1004 to 1806, Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, and Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

from 1526, and Archduke of Austria from 1521 until his death in 1564.Milan Kruhek: Cetin, grad izbornog sabora Kraljevine Hrvatske 1527, Karlovačka Županija, 1997, Karslovac Before his accession as Emperor, he ruled the Austrian hereditary lands of the Habsburgs in the name of his elder brother, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (Crown of Castile, Castil ...

. Also, he often served as Charles' representative in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

and developed encouraging relationships with German princes. In addition, Ferdinand also developed valuable relationships with the German banking house of Jakob Fugger and the Catalan bank, Banca Palenzuela Levi Kahana.

The key events during his reign were the conflict with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, which in the 1520s began a great advance into Central Europe, and the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, which resulted in several wars of religion. Although not a military leader, Ferdinand was a capable organizer with institutional imagination who focused on building a centralized government for Austria, Hungary, and Czechia instead of striving for universal monarchy. He reintroduced major innovations of his grandfather Maximilian I Maximilian I may refer to:

*Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, reigned 1486/93–1519

*Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, reigned 1597–1651

*Maximilian I, Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (1636-1689)

*Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria, reigned 1795� ...

such as the ''Hofrat'' (court council) with a chancellery and a treasury attached to it (this time, the structure would last until the reform of Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

) and added innovations of his own such as the ''Raitkammer'' (collections office) and the War Council, conceived to counter the threat from the Ottoman Empire, while also successfully subduing the most radical of his rebellious Austrian subjects and turning the political class in Bohemia and Hungary into Habsburg partners. While he was able to introduce uniform models of administration, the governments of Austria, Bohemia and Hungary remained distinct though. His approach to Imperial problems, including governance, human relations and religious matters was generally flexible, moderate and tolerant. Ferdinand's motto was : "Let justice be done, though the world perish".

Biography

Overview

Ferdinand was born in 1503 inAlcalá de Henares

Alcalá de Henares () is a Spanish city in the Community of Madrid. Straddling the Henares River, it is located to the northeast of the centre of Madrid. , it has a population of 193,751, making it the region's third-most populated Municipalities ...

, Castile, the second son of Philip I of Castile and Joanna of Castile. He shared the same name, birthday and customs with his maternal grandfather Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

. He was born, raised, and educated in Castile, and did not learn German until he was a young adult.

In the summer of 1518 Ferdinand was sent to Flanders following his brother Charles's arrival in Castile as newly appointed King Charles I the previous autumn. Ferdinand returned in command of his brother's fleet but en route was blown off-course and spent four days in Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a population of 5,281 (a ...

in Ireland before reaching his destination. With the death of his grandfather Maximilian I and the accession of his now 19-year-old brother, Charles V, to the title of the Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, Ferdinand was entrusted with the government of the Austrian hereditary lands, roughly modern-day Austria and Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

. He was Archduke of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

from 1521 to 1564. Though he supported his brother, Ferdinand also managed to strengthen his own realm. By adopting the German language and culture later in his life, he also grew close to the German territorial princes.

After the death of his brother-in-law Louis II, Ferdinand ruled as King of Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

and Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

(1526–1564).Ferdinand I, Holy Roman emperorThe Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001. Ferdinand also served as his brother's deputy in the Holy Roman Empire during his brother's many absences, and in 1531 was elected

King of the Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: König der Römer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

, making him Charles's designated heir in the empire. Charles abdicated in 1556 and Ferdinand adopted the title "Emperor elect", with the ratification of the Imperial diet taking place in 1558, while the kingdoms in the Iberian peninsula, the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, and Franche-Comté

Franche-Comté (, ; ; Frainc-Comtou: ''Fraintche-Comtè''; frp, Franche-Comtât; also german: Freigrafschaft; es, Franco Condado; all ) is a cultural and historical region of eastern France. It is composed of the modern departments of Doubs, ...

went to Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

, son of Charles.

Hungary and the Ottomans

According to the terms set at the First Congress of Vienna in 1515, Ferdinand married Anne Jagiellonica, daughter of King Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary on 22 July 1515. Both Hungary and Bohemia were

According to the terms set at the First Congress of Vienna in 1515, Ferdinand married Anne Jagiellonica, daughter of King Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary on 22 July 1515. Both Hungary and Bohemia were elective monarchies

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by an elected monarch, in contrast to a hereditary monarchy in which the office is automatically passed down as a family inheritance. The manner of election, the nature of candidate qualifications, and th ...

, where the parliaments had the sovereign right to decide about the person of the king. Therefore, after the death of his brother-in-law Louis II, King of Bohemia and of Hungary, at the battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and those ...

on 29 August 1526, Ferdinand immediately applied to the parliaments of Hungary and Bohemia to participate as a candidate in the king elections. On 24 October 1526 the Bohemian Diet

The Bohemian Diet ( cs, Český zemský sněm, german: Böhmischer Landtag) was the parliament of the Kingdom of Bohemia within the Austro-Hungarian Empire between 1861 and Czechoslovak independence in 1918.

The Diet during the Absolutist Per ...

, acting under the influence of chancellor Adam of Hradce

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

, elected Ferdinand King of Bohemia under conditions of confirming traditional privileges of the estates and also moving the Habsburg court to Prague. The success was only partial, as the Diet refused to recognise Ferdinand as hereditary lord of the Kingdom.

The throne of Hungary became the subject of a dynastic dispute between Ferdinand and John Zápolya, Voivode of Transylvania. They were supported by different factions of the nobility in the Hungarian kingdom. Ferdinand also had the support of his brother, the Emperor Charles V.

On 10 November 1526, John Zápolya was proclaimed king by a Diet at Székesfehérvár, elected in the parliament by the untitled lesser nobility (gentry).

Nicolaus Olahus

Nicolaus Olahus (Latin for ''Nicholas, the Vlach''; hu, Oláh Miklós; ro, Nicolae Valahul); 10 January 1493 – 15 January 1568) was the Archdiocese of Esztergom, Archbishop of Esztergom, Prince primate, Primate of Kingdom of Hungary, Hungary, ...

, secretary of Louis, attached himself to the party of Ferdinand but retained his position with his sister, Queen Dowager Mary. Ferdinand was also elected King of Hungary, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, etc. by the higher aristocracy (the magnates or barons) and the Hungarian Catholic clergy in a rump Diet in Pozsony (''Bratislava'' in Slovak) on 17 December 1526. Accordingly, Ferdinand was crowned as King of Hungary in the Székesfehérvár Basilica on 3 November, 1527.

The Croatian nobles unanimously accepted the Pozsony election of Ferdinand I, receiving him as their king in the 1527 election in Cetin

The 1527 election in Cetin ( hr, Cetinski / Cetingradski sabor, meaning Parliament on Cetin(grad) or Parliament of Cetin(grad), or ) was an assembly of the Croatian Parliament in the Cetin Castle in 1527. It followed a succession crisis in the Kin ...

, and confirming the succession to him and his heirs. In return for the throne, Archduke Ferdinand promised to respect the historic rights, freedoms, laws and customs of the Croats when they united with the Hungarian kingdom and to defend Croatia from Ottoman invasion.

Brendan Simms notes that the reason Ferdinand was able to gain this sphere of power was Charles V's difficulties in coordinating between the Austrian, Hungarian fronts and his Mediterranean fronts in the face of the Ottoman threat, as well as in his German, Burgundian and Italian theatres of war against German Protestant Princes and France. Thus the defense of central Europe was subcontracted to Ferdinand as well as many responsibilities involving the management of the Empire. Charles V abdicated as archduke of Austriain 1522, and nine years after that he had the German princes elect Ferdinand as King of the Romans, who thus became his designated successor. "This had profound implications for state formation in south-eastern Europe. Ferdinand rescued Bohemia and Silesia from the Hungarian wreckage, making his north-eastern flank more secure. He told the Landtag, the

assembled representatives of the nobility, at Linz in 1530 that 'the Turks cannot be resisted unless the Kingdom of Hungary was in the hands of an Archduke of Austria or another German prince'. After some hesitation, Croatia and the Hungarian rump joined the Habsburgs. In both cases, the link was essentially a contractual one, directly linked to Ferdinand’s ability to provide protection against the Turks."

The Austrian lands were in miserable economic and financial conditions, but Ferdinand was forced to introduce the so-called Turkish Tax (Türken Steuer) in view of the Ottoman threat. In spite of the huge Austrian sacrifices, he was not able to collect enough money to pay for the expenses of the defence costs of Austrian lands. His annual revenues only allowed him to hire 5,000 mercenaries for two months, thus Ferdinand asked for help from his brother, Emperor Charles V, and started to borrow money from rich bankers like the Fugger family.

Ferdinand defeated Zápolya at the Battle of Tarcal

The Battle of Tarcal or Battle of Tokaj ( hu, Tarcali csata) was a battle fought on 27 September 1527 near Tokaj between the Habsburg-German-Hungarian forces of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria and an opposing Hungarian army under the command of J ...

in September 1527 and again in the Battle of Szina

The Battle of Szina or Seňa took place near Szina in the Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Seňa, in Slovakia). The battle was fought on 20 March 1528 between two rival kings of Hungary John Zápolya and Ferdinand I. The latter's forces under c ...

in March 1528. Zápolya fled the country and applied to Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent for support, making Hungary an Ottoman vassal state.

This led to the most dangerous moment of Ferdinand's career, in 1529, when Suleiman took advantage of this Hungarian support for a massive but ultimately unsuccessful assault on Ferdinand's capital: the Siege of Vienna Sieges of Vienna may refer to:

* Siege of Vienna (1239)

* Siege of Vienna (1276)

* Siege of Vienna (1287)

* Siege of Vienna (1477), unsuccessful Hungarian attempt during the Austro–Hungarian War.

*Siege of Vienna (1485), Hungarian victory during ...

, which sent Ferdinand to refuge in Bohemia. A further Ottoman invasion was repelled in 1532 (see Siege of Güns

The siege of Kőszeg ( hu, Kőszeg ostroma) or siege of Güns ( tr, Güns Kuşatması), also known as German Campaign ( tr, Alman Seferi) was a siege of Kőszeg (german: Güns)During the Ottoman–Habsburg wars, the small border fort was called G ...

). In that year Ferdinand made peace with the Ottomans, splitting Hungary into a Habsburg sector in the west and John Zápolya's domain in the east, the latter effectively a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire.

Together with the formation of the Schmalkaldic League in 1531, this struggle with the Ottomans caused Ferdinand to grant the Nuremberg Religious Peace

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century.

Although created for religious motives soon after the start of the Reformation, its members later came to ...

. As long as he hoped for a favorable response from his humiliating overtures to Suleiman, Ferdinand was not inclined to grant the peace which the Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

demanded at the Diet of Regensburg Diet of Regensburg may refer any of the sessions of the Imperial Diet, Imperial States, or the prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire which took place in the Imperial City of Regensburg (Ratisbon), now in Germany.

An incomplete lists of Diets o ...

which met in April 1532. But as the army of Suleiman drew nearer he yielded and on 23 July 1532 the peace was concluded at Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

where the final deliberations took place. Those who had up to this time joined the Reformation obtained religious liberty until the meeting of a council and in a separate compact all proceedings in matters of religion pending before the imperial chamber court were temporarily paused.

In 1538, in the Treaty of Nagyvárad, Ferdinand induced the childless Zápolya to name him as his successor. But in 1540, just before his death, Zápolya had a son,

In 1538, in the Treaty of Nagyvárad, Ferdinand induced the childless Zápolya to name him as his successor. But in 1540, just before his death, Zápolya had a son, John II Sigismund

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, who was promptly elected King by the Diet. Ferdinand invaded Hungary, but the regent, Frater George Martinuzzi, Bishop of Várad, called on the Ottomans for protection. Suleiman marched into Hungary (see Siege of Buda (1541)

The siege of Buda (4 May – 21 August 1541) ended with the capture of the city of Buda, Hungary by the Ottoman Empire, leading to 150 years of Ottoman control of Hungary. The siege, part of the Little War in Hungary, was one of the most importa ...

) and not only drove Ferdinand out of central Hungary, he forced Ferdinand to agree to pay tribute for his lands in western Hungary.

John II Sigismund was also supported by King Sigismund I of Poland, his mother's father, but in 1543 Sigismund made a treaty with the Habsburgs and Poland became neutral. Prince Sigismund Augustus married Elisabeth of Austria, Ferdinand's daughter.

Suleiman had allocated Transylvania and eastern Royal Hungary

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

to John II Sigismund, which became the "Eastern Hungarian Kingdom

The Eastern Hungarian Kingdom ( hu, keleti Magyar Királyság) is a modern term coined by some historians to designate the realm of John Zápolya and his son John Sigismund Zápolya, who contested the claims of the House of Habsburg to rule the ...

", reigned over by his mother, Isabella Jagiellon, with Martinuzzi as the real power. But Isabella's hostile intrigues and threats from the Ottomans led Martinuzzi to switch round. In 1549, he agreed to support Ferdinand's claim, and Imperial armies marched into Transylvania. In the Treaty of Weissenburg

The Treaty of Weissenburg (german: Vertrag von Weißenburg or ''Weißenburger Vertrag'') declared Archduke Ferdinand of Austria the ruler of Royal Hungary and Transylvania. It was signed in Weissenburg (Gyulafehérvár) on 19 July 1551. The territ ...

(1551), Isabella agreed on behalf of John II Sigismund to abdicate as King of Hungary and to hand over the royal crown and regalia. Thus Royal Hungary and Transylvania went to Ferdinand, who agreed to recognise John II Sigismund as vassal Prince of Transylvania and betrothed one of his daughters to him. Meanwhile, Martinuzzi attempted to keep the Ottomans happy even after they responded by sending troops. Ferdinand's general Castaldo suspected Martinuzzi of treason and with Ferdinand's approval had him killed.

Since Martinuzzi was by this time an archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

and Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

, this was a shocking act, and Pope Julius III

Pope Julius III ( la, Iulius PP. III; it, Giulio III; 10 September 1487 – 23 March 1555), born Giovanni Maria Ciocchi del Monte, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 February 1550 to his death in March 155 ...

excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

Castaldo and Ferdinand. Ferdinand sent the Pope a long accusation of treason against Martinuzzi in 87 articles, supported by 116 witnesses. The Pope exonerated Ferdinand and lifted the excommunications in 1555.George Martinuzzientry in the

Catholic Encyclopedia

The ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'' (also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedia'') i ...

The war in Hungary continued. Ferdinand was unable to keep the Ottomans out of Hungary. In 1554, Ferdinand sent Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq

Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq (1522 in Comines – 29 October 1592 in Saint-Germain-sous-Cailly; la, Augerius Gislenius Busbequius), sometimes Augier Ghislain de Busbecq, was a 16th-century Flemish writer, herbalist and diplomat in the employ ...

to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

to discuss a border treaty with Suleiman, but he could achieve nothing. In 1556 the Diet returned John II Sigismund to the eastern Hungarian throne, where he remained until 1570. De Busbecq returned to Constantinople in 1556, and succeeded on his second try.

The Austrian branch of Habsburg monarchs needed the economic power of Hungary for the Ottoman wars. During the Ottoman wars the territory of the former Kingdom of Hungary shrunk by around 70%. Despite these enormous territorial and demographic losses, the smaller, heavily war-torn Royal Hungary

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

had remained economically more important to the Habsburg rulers than Austria or Kingdom of Bohemia even at the end of the 16th century. Out of all his countries, the depleted Kingdom of Hungary was, at that time, Ferdinand's largest source of revenue.

Consolidation of power in Bohemia

When he took control of the Bohemian lands in the 1520s, their religious situation was complex. Its German population was composed of Catholics and Lutherans. Some Czechs were receptive to Lutheranism, but most of them adhered to Utraquist Hussitism, while a minority of them adhered toRoman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. A significant number of Utraquists favoured an alliance with the Protestants.''Between Lipany and White Mountain'', Palmitessa At first, Ferdinand accepted this situation and he gave considerable freedom to the Bohemian estates. In the 1540s, the situation changed. In Germany, while most Protestant princes had hitherto favored negotiation with the Emperor and while many had supported him in his wars, they became increasingly confrontational during this decade. Some of them even went to war against the Empire, and many Bohemian (German or Czech) Protestants or Utraquists sympathized with them.

Ferdinand and his son Maximilian participated in the victorious campaign of Charles V against the German Protestants in 1547. The same year, he also defeated a Protestant revolt in Bohemia, where the estates and a large part of the nobility had denied him support in the German campaign. This allowed him to increase his power in this realm. He centralized his administration, revoked many urban privileges and confiscated properties. Ferdinand also sought to strengthen the position of the Catholic church in the Bohemian lands, and favoured the installation of the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

there.

Ferdinand and the Augsburg Peace of 1555

In the 1550s, Ferdinand managed to win some key victories on the imperial scene. Unlike his brother, he opposed Albrecht of Brandenburg-Kulmbach and participated in his defeat. This defeat, along with his German ways, made Ferdinand more popular than the Emperor among Protestant princes. This allowed him to play a critical role in the settlement of the religious issue in the Empire. After decades of religious and political unrest in the German states, Charles V ordered a general Diet in Augsburg at which the various states would discuss the religious problem and its solution. Charles himself did not attend, and delegated authority to his brother, Ferdinand, to "act and settle" disputes of territory, religion and local power.Holborn, p. 241. At the conference, which opened on 5 February, Ferdinand cajoled, persuaded and threatened the various representatives into agreement on three important principles promulgated on 25 September: # The principle of ' ("Whose realm, his religion") provided for internal religious unity within a state: the religion of the prince became the religion of the state and all its inhabitants. Those inhabitants who could not conform to the prince's religion were allowed to leave, an innovative idea in the sixteenth century. This principle was discussed at length by the various delegates, who finally reached agreement on the specifics of its wording after examining the problem and the proposed solution from every possible angle. # The second principle, called the ' (ecclesiastical reservation), covered the special status of the ecclesiastical state. If the prelate of an ecclesiastic state changed his religion, the men and women living in that state did not have to do so. Instead, the prelate was expected to resign from his post, although this was not spelled out in the agreement. # The third principle, known as ' (Ferdinand's Declaration), exempted knights and some of the cities from the requirement of religious uniformity, if the reformed religion had been practised there since the mid-1520s, allowing for a few mixed cities and towns where Catholics and Lutherans had lived together. It also protected the authority of the princely families, the knights and some of the cities to determine what religious uniformity meant in their territories. Ferdinand inserted this at the last minute, on his own authority.Problems with the Augsburg settlement

After 1555, the Peace of Augsburg became the legitimating legal document governing the co-existence of the Lutheran and Catholic faiths in the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, and it served to ameliorate many of the tensions between followers of the "Old Faith" (

After 1555, the Peace of Augsburg became the legitimating legal document governing the co-existence of the Lutheran and Catholic faiths in the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, and it served to ameliorate many of the tensions between followers of the "Old Faith" (Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

) and the followers of Luther, but it had two fundamental flaws. First, Ferdinand had rushed the article on ' through the debate; it had not undergone the scrutiny and discussion that attended the widespread acceptance and support of '. Consequently, its wording did not cover all, or even most, potential legal scenarios. The ' was not debated in plenary session at all; using his authority to "act and settle," Ferdinand had added it at the last minute, responding to lobbying by princely families and knights.

While these specific failings came back to haunt the Empire in subsequent decades, perhaps the greatest weakness of the Peace of Augsburg was its failure to take into account the growing diversity of religious expression emerging in the so-called evangelical and reformed traditions. Other confessions had acquired popular, if not legal, legitimacy in the intervening decades and by 1555, the reforms proposed by Luther were no longer the only possibilities of religious expression: Anabaptists, such as the Frisian Menno Simons (1492–1559) and his followers; the followers of John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

, who were particularly strong in the southwest and the northwest; and the followers of Huldrych Zwingli were excluded from considerations and protections under the Peace of Augsburg. According to the Augsburg agreement, their religious beliefs remained heretical.Holborn, pp. 243–246.

Charles V's abdication

In 1556, amid great pomp, and leaning on the shoulder of one of his favourites (the 24-year-old William, Count of Nassau and Orange), Charles gave away his lands and his offices. TheSpanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, which included Spain, the Netherlands, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Milan and Spain's possessions in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

, went to his son, Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

. Ferdinand became suo jure monarch in Austria and succeeded Charles as Holy Roman Emperor. This course of events had been guaranteed already on 5 January 1531 when Ferdinand had been elected the King of the Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: König der Römer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

and so the legitimate successor of the reigning Emperor.

Charles's choices were appropriate. Philip was culturally Spanish: he was born in

Charles's choices were appropriate. Philip was culturally Spanish: he was born in Valladolid

Valladolid () is a Municipalities of Spain, municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province o ...

and raised in the Spanish court, his native tongue was Spanish, and he preferred to live in Spain. Ferdinand was familiar with, and to, the other princes of the Holy Roman Empire. Although he too had been born in Spain, he had administered his brother's affairs in the Empire since 1531. Some historians maintain Ferdinand had also been touched by the reformed philosophies, and was probably the closest the Holy Roman Empire ever came to a Protestant emperor; he remained nominally a Catholic throughout his life, although reportedly he refused last rites on his deathbed. Other historians maintain he was as Catholic as his brother, but tended to see religion as outside the political sphere.

Charles' abdication had far-reaching consequences in imperial diplomatic relations with France and the Netherlands, particularly in his allotment of the Spanish kingdom to Philip. In France, the kings and their ministers grew increasingly uneasy about Habsburg encirclement and sought allies against Habsburg hegemony from among the border German territories, and even from some of the Protestant kings. In the Netherlands, Philip's ascension in Spain raised particular problems; for the sake of harmony, order, and prosperity Charles had not blocked the Reformation, and had tolerated a high level of local autonomy. An ardent Catholic and rigidly autocratic prince, Philip pursued an aggressive political, economic and religious policy toward the Dutch, resulting in a Dutch rebellion shortly after he became king. Philip's militant response meant the occupation of much of the upper provinces by troops of, or hired by, Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain is a contemporary historiographical term referring to the huge extent of territories (including modern-day Spain, a piece of south-east France, eventually Portugal, and many other lands outside of the Iberian Peninsula) ruled be ...

and the constant ebb and flow of Spanish men and provisions on the so-called Spanish road from northern Italy, through the Burgundian Burgundian can refer to any of the following:

*Someone or something from Burgundy.

*Burgundians, an East Germanic tribe, who first appear in history in South East Europe. Later Burgundians colonised the area of Gaul that is now known as Burgundy (F ...

lands, to and from Flanders.

Holy Roman Emperor (1556–1564)

Charles abdicated as Emperor in August 1556 in favor of his brother Ferdinand. Given the settlement of 1521 and the election of 1531, Ferdinand became Holy Roman Emperor and '' suo jure'' Archduke of Austria. Due to lengthy debate and bureaucratic procedure, the Imperial Diet did not accept the Imperial succession until 3 May 1558. The Pope refused to recognize Ferdinand as Emperor until 1559, when peace was reached between France and the Habsburgs. During his Emperorship, the

Charles abdicated as Emperor in August 1556 in favor of his brother Ferdinand. Given the settlement of 1521 and the election of 1531, Ferdinand became Holy Roman Emperor and '' suo jure'' Archduke of Austria. Due to lengthy debate and bureaucratic procedure, the Imperial Diet did not accept the Imperial succession until 3 May 1558. The Pope refused to recognize Ferdinand as Emperor until 1559, when peace was reached between France and the Habsburgs. During his Emperorship, the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trento, Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italian Peninsula, Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation ...

came to an end. Ferdinand organized an Imperial election in 1562 in order to secure the succession of his son Maximilian II. Venetian ambassadors to Ferdinand recall in their Relazioni the Emperor's pragmatism and his ability to speak multiple languages. Several issues of the Council of Trent were solved after a compromise was personally reached between Emperor Ferdinand and Morone, the papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

.

In the Empire

An important invention of Ferdinand was the '' Hofkriegsrat'' (Aulic War Council), officially established in 1556 to coordinate military affairs in all Habsburg lands (inside and outside the Holy Roman Empire). Together with the (established in 1559, merging the Imperial and Austrian Chancelleries, thus also dealing with affairs of both Imperial and Habsburg lands) and the (the Finance Chamber, which received imperial taxes from the ''Reichspfennig meister''), it formed the core of the Habsburg government in Vienna. The ''Reichshofrat

The Aulic Council ( la, Consilium Aulicum, german: Reichshofrat, literally meaning Court Council of the Empire) was one of the two supreme courts of the Holy Roman Empire, the other being the Imperial Chamber Court. It had not only concurrent juris ...

'' was revived to deal with affairs concerning imperial prerogatives. In 1556, an ordinance was issued to ensure imperial and dynastic affairs were managed separately (by two groups of officials from the same institution) though. In his time, the influence of the Estates in these institutions were limited. For each ''Länder'' group, regiments (or governments) and treasury offices were created.

Unlike Maximilian I and Charles V, Ferdinand I was not a nomadic ruler. In 1533, he moved his residence to Vienna and spent most of his time there. After experiencing the Turkish siege of 1529, Ferdinand worked hard to make Vienna an impregnable fortress. After his 1558 accession, Vienna became the imperial capital.

Administration of Royal Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia

Since 1542, Charles V and Ferdinand had been able to collect the Common Penny tax, or ''Türkenhilfe'' (Turkish aid), designed to protect the Empire against the Ottomans or France. But as Hungary, unlike Bohemia, was not part of the Reich, the imperial aid for Hungary depended on political factors. The obligation was only in effect if Vienna or the Empire was threatened.

The western part of Hungary over which Ferdinand had dominion became known as

Since 1542, Charles V and Ferdinand had been able to collect the Common Penny tax, or ''Türkenhilfe'' (Turkish aid), designed to protect the Empire against the Ottomans or France. But as Hungary, unlike Bohemia, was not part of the Reich, the imperial aid for Hungary depended on political factors. The obligation was only in effect if Vienna or the Empire was threatened.

The western part of Hungary over which Ferdinand had dominion became known as Royal Hungary

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

. As the ruler of Austria, Bohemia and Royal Hungary, Ferdinand adopted a policy of centralisation and, in common with other monarchs of the time, the construction of an absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

. In 1527, soon after ascending the throne, he published a constitution for his hereditary domains (') and established Austrian-style institutions in Pressburg

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

for Hungary, in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

for Bohemia, and in Breslau for Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

.

Ferdinand was able to introduce more uniform governments for his realms and also strengthen his control over finance in Bohemia, which provided him with half of his revenue. The governments basically remained independent of each other though. An Austrian could make a career in Bohemian administration but usually only after naturalization, except for some royal protégés such as Florian Griespeck, while it was virtually unheard of (in contrast with the future) for a Bohemian to gain advancement in the Austrian government. An elected king himself, he gradually nudged the monarchy towards becoming hereditary, which would finally succeed under Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor

Ferdinand II (9 July 1578 – 15 February 1637) was Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia, King of Hungary, Hungary, and List of Croatian monarchs, Croatia from 1619 until his death in 1637. He was the son of Charles II, Archduke of Austria, Archd ...

.

In 1547 the Bohemian Estates

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

rebelled against Ferdinand after he had ordered the Bohemian army to move against the German Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

. After suppressing the revolt, he retaliated by limiting the privileges of Bohemian cities and inserting a new bureaucracy of royal officials to control urban authorities.

Ferdinand was a supporter of the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

and helped lead the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

response against what he saw as the heretical tide of Protestantism. For example, in 1551 he invited the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

to Vienna and in 1556 to Prague. Finally, in 1561 Ferdinand revived the Archdiocese of Prague, which had been previously liquidated due to the success of the Protestants.

After the Ottoman invasion of Hungary the traditional Hungarian coronation city Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár (; german: Stuhlweißenburg ), known colloquially as Fehérvár ("white castle"), is a city in central Hungary, and the country's ninth-largest city. It is the regional capital of Central Transdanubia, and the centre of Fejér ...

came under Turkish occupation. Thus, in 1536 the Hungarian Diet decided that a new place for coronation of the king as well as a meeting place for the Diet itself would be set in Pressburg

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

. Ferdinand proposed that the Hungarian and Bohemian diets should convene and hold debates together with the Austrian estates, but all parties refused such an innovation.

In Hungary, the monarchy remained elective until 1627 (with Habsburgs' female inheritance rights being acknowledged in 1723), although the kings that followed Ferdinand would almost always be Habsburgs.

A rudimentary union between Austria, Hungary and Bohemia was formed though, on the basis of common legal status. Ferdinand had an interest in keeping Bohemia separate from imperial jurisdiction and making the connection between Bohemia and the Empire looser (Bohemia did not have to pay taxes to the Empire). As he refused the rights of an Imperial Elector as King of Bohemia, he was able to give Bohemia (as well as associated territories such as Upper and Lower Alsatia, Silesia and Moravia) the same privileged status as Austria, therefore affirming his superior position in the Empire.

Death and succession

Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

in 1564 and is buried in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague. After his death, Maximilian ascended unchallenged.

Legacy

Ferdinand's legacy ultimately proved enduring. Though lacking resources, he managed to defend his land against the Ottomans with limited support from his brother, and even secured a part of Hungary that would later provide the basis for the conquest of the whole kingdom by the Habsburgs. In his own possessions, he built a tax system that, though imperfect, would continue to be used by his successors. His handling of the Protestant Reformation proved more flexible and more effective than that of his brother and he played a key part in the settlement of 1555, which started an era of peace in Germany. His statesmanship, overall, was cautious and effective. On the other hand, when he engaged in more audacious endeavours, like his offensives against Buda and Pest, it often ended in failure.

Fichtner remarks that Ferdinand was a mediocre military commander (thus the many difficulties in dealing with the Ottomans in Hungary) but an energetic and very imaginative administrator, who produced a framework for his empire that would endured into the eighteenth century. The core included a court council, privy council, central treasury and a body for military affairs, with the written business conducted by a common chancery. In his time and in practice, Bohemia and Hungary resisted cooperating with the structure but the German territories widely imitated it.

Ferdinand was also a patron of the arts. He embellished Vienna and Prague. The

Ferdinand's legacy ultimately proved enduring. Though lacking resources, he managed to defend his land against the Ottomans with limited support from his brother, and even secured a part of Hungary that would later provide the basis for the conquest of the whole kingdom by the Habsburgs. In his own possessions, he built a tax system that, though imperfect, would continue to be used by his successors. His handling of the Protestant Reformation proved more flexible and more effective than that of his brother and he played a key part in the settlement of 1555, which started an era of peace in Germany. His statesmanship, overall, was cautious and effective. On the other hand, when he engaged in more audacious endeavours, like his offensives against Buda and Pest, it often ended in failure.

Fichtner remarks that Ferdinand was a mediocre military commander (thus the many difficulties in dealing with the Ottomans in Hungary) but an energetic and very imaginative administrator, who produced a framework for his empire that would endured into the eighteenth century. The core included a court council, privy council, central treasury and a body for military affairs, with the written business conducted by a common chancery. In his time and in practice, Bohemia and Hungary resisted cooperating with the structure but the German territories widely imitated it.

Ferdinand was also a patron of the arts. He embellished Vienna and Prague. The University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich histor ...

was reorganized. He also called Jesuits to the capital city, attracted architects and scholars from Italy and the Low Countries to create an intellectual ''milieu'' surrounding the court. He promoted scholarly interest in Oriental languages. The humanists he invited had a major influence on his son Maximilian. He was particularly fond of music and hunting. While not a supremely gifted commander, he was interested in military matters and participated in several campaigns during his reign.

He was the last King of Germany crowned in Aachen.

Name in other languages

German, Czech,Slovenian

Slovene or Slovenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Slovenia, a country in Central Europe

* Slovene language, a South Slavic language mainly spoken in Slovenia

* Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( sl, Sloven ...

, Slovak, Serbian

Serbian may refer to:

* someone or something related to Serbia, a country in Southeastern Europe

* someone or something related to the Serbs, a South Slavic people

* Serbian language

* Serbian names

See also

*

*

* Old Serbian (disambiguat ...

, hr, Ferdinand I.; hu, I. Ferdinánd; es, link=no, Fernando I; tr, 1. Ferdinand; pl, Ferdynand I.

Marriage and children

On 26 May 1521 inLinz

Linz ( , ; cs, Linec) is the capital of Upper Austria and third-largest city in Austria. In the north of the country, it is on the Danube south of the Czech border. In 2018, the population was 204,846.

In 2009, it was a European Capital of ...

, Austria, Ferdinand married Anna of Bohemia and Hungary (1503–1547), daughter of Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary and his wife Anne of Foix-Candale. They had fifteen children, all but two of whom reached adulthood:

Heraldry

Ancestors

Coinage

Ferdinand I has been the main motif for many collector coins and medals. The most recent one is the Austrian silver 20-euro Renaissance coin issued on 12 June 2002. A portrait of Ferdinand I is shown on the reverse of the coin, while on the obverse a view of the Swiss Gate of the Hofburg Palace can be seen.See also

* Parade armor of Ferdinand I * Kings of Germany family tree * First Congress of Vienna in 1515 *Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and those ...

in 1526

* Louis II of Hungary

* John Zápolya, disputed king of Hungary 1526–40

* Ivan Karlović, Banus of Croatia 1521–24 and 1527–31

* Petar Keglević

Petar Keglević II of Bužim (died in 1554 or 1555) was the ban of Croatia and Slavonia from 1537 to 1542.

Career

Keglević was captain from 1521 to 1522 and later ban of Jajce. In 1526, some months before the Battle of Mohács, he got the '' ...

, Banus of Croatia 1537–42

* Pavle Bakic Pavle (Macedonian and sr-cyr, Павле; ka, პავლე) is a Serbian, Macedonian, Croatian and Georgian male given name corresponding to English Paul; the name is of biblical origin (cf. Saint Paul).

People known mononymously as Pavle incl ...

, last Despot of Serbia

The Serbian Despotate ( sr, / ) was a medieval Serbian state in the first half of the 15th century. Although the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 is generally considered the end of medieval Serbia, the Despotate, a successor of the Serbian Empire and ...

to be recognised by Ferdinand I and Holy Roman Empire in 1537

* Jovan Nenad

Jovan Nenad ( sr-cyr, Јован Ненад; hu, Fekete Iván or ; ca. 1492 – 26 July 1527), known as ''the Black'' was a Serb military commander in the service of the Kingdom of Hungary who took advantage of a Hungarian military defeat at Moh ...

, self-proclaimed Emperor of Vojvodina

* Balthasar Hubmaier, Anabaptist theologian, executed by burning

Notes

References

Sources

* * * *Further reading

* Fichtner, Paula S. ''Ferdinand I of Austria: The Politics of Dynasticism in the Age of the Reformation''. Boulder, CO: East European Monographs, 1982.External links

A pedigree of the Habsburg

* *

Biography of the website of the ''Residenzen-Kommission''

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Ferdinand 1, Holy Roman Emperor 1503 births 1564 deaths 16th-century Holy Roman Emperors 16th-century archdukes of Austria Burials at St. Vitus Cathedral Knights of the Garter Knights of the Golden Fleece Spanish infantes Aragonese infantes Castilian infantes Nobility from Madrid People from Alcalá de Henares 16th-century Spanish people Dukes of Carniola