Emery, Utah on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Emery is a town in

Two significant Fremont culture sites are located north and south of the town. Artifacts such as pottery, manos and

Two significant Fremont culture sites are located north and south of the town. Artifacts such as pottery, manos and  A sizable herd of

A sizable herd of

The first settlers to Emery came from

The first settlers to Emery came from  1883 was a red-letter year for Casper Christensen. On 15 April, he was set apart as the Presiding Elder of the Muddy Creek Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. On the 26th of August, his daughter, Bellette, was born, the first baby girl to be born on the Muddy Creek. On 2 September, the Emery Ward was organized with Casper Christensen as bishop. Then on 19 November, he was officially appointed postmaster at Muddy, in the County of Emery in the Utah Territory. His daughter, Hannah, was appointed as his assistant.

When Casper Christensen was first appointed postmaster and bishop, a postal inspector found him working in the field and tried to make him understand that he wanted to inspect his postal records. Finally, in desperation, he said, "You don't seem to know who I am. I am a postal inspector." Brother Casper indignantly replied, "And YOU don't know who I am. I'm the Bishop on the Creek!" Town residents have continued to use this phrase when dealing with someone who was self-important.

1883 was a red-letter year for Casper Christensen. On 15 April, he was set apart as the Presiding Elder of the Muddy Creek Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. On the 26th of August, his daughter, Bellette, was born, the first baby girl to be born on the Muddy Creek. On 2 September, the Emery Ward was organized with Casper Christensen as bishop. Then on 19 November, he was officially appointed postmaster at Muddy, in the County of Emery in the Utah Territory. His daughter, Hannah, was appointed as his assistant.

When Casper Christensen was first appointed postmaster and bishop, a postal inspector found him working in the field and tried to make him understand that he wanted to inspect his postal records. Finally, in desperation, he said, "You don't seem to know who I am. I am a postal inspector." Brother Casper indignantly replied, "And YOU don't know who I am. I'm the Bishop on the Creek!" Town residents have continued to use this phrase when dealing with someone who was self-important.

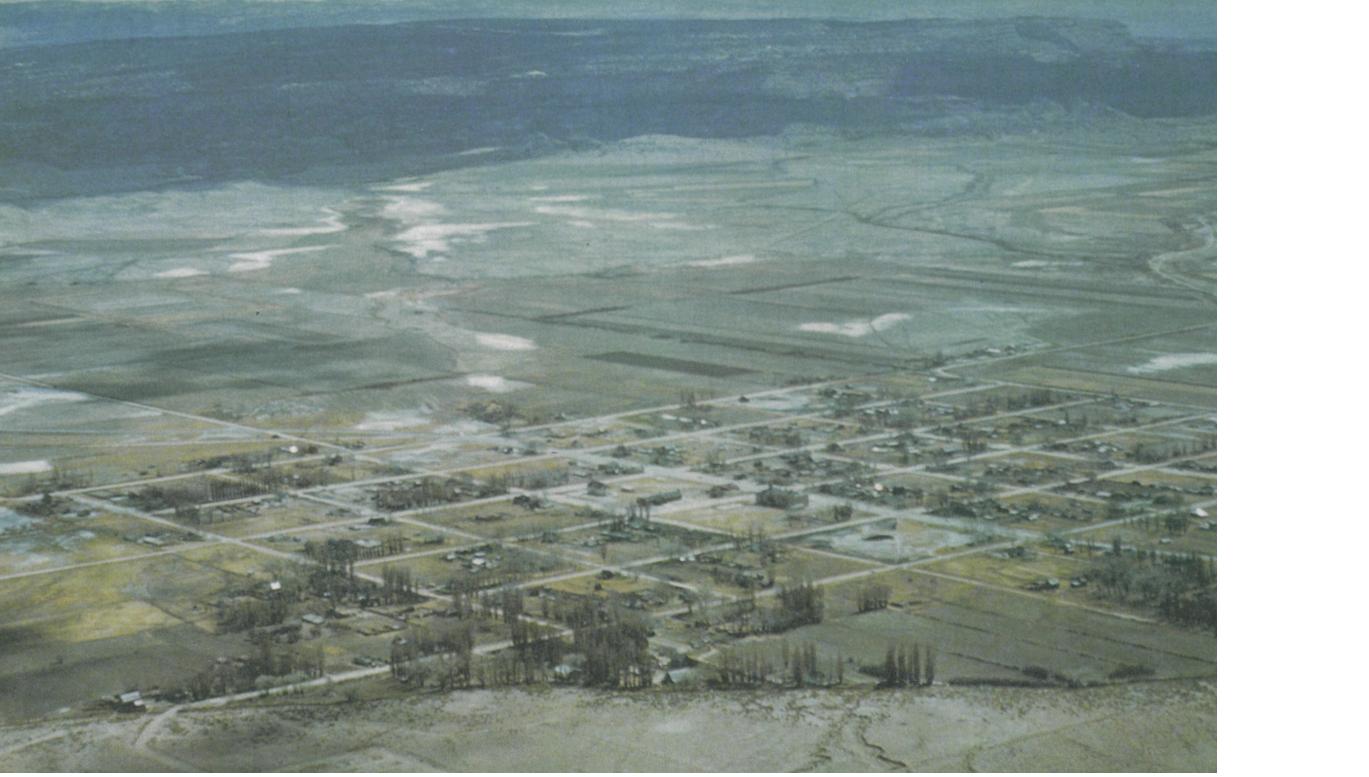

Muddy Creek and Quitchupah residents consolidated on this new townsite.

Muddy Creek and Quitchupah residents consolidated on this new townsite.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 28.9% under 18, 5.8% from 18 to 24, 19.2% from 25 to 44, 24.4% from 45 to 64, and 21.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.7 males. For every 100 females aged 18 and over, there were 97.3 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $40,469, and the median income for a family was $51,875. Males had a median income of $40,104 versus $31,250 for females. The

In the town, the population was spread out, with 28.9% under 18, 5.8% from 18 to 24, 19.2% from 25 to 44, 24.4% from 45 to 64, and 21.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.7 males. For every 100 females aged 18 and over, there were 97.3 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $40,469, and the median income for a family was $51,875. Males had a median income of $40,104 versus $31,250 for females. The

Emery Town

at Emery County's official website {{authority control Towns in Emery County, Utah Towns in Utah Populated places established in 1882

Emery County

Emery County is a county in east-central Utah, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population was 10,976. Its county seat is Castle Dale, and the largest city is Huntington.

History Prehistory

Occupation of the San Rafael ...

, Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, United States. The population was 288 at the 2010 census.

History

Prehistoric

Emery sits at the base of the mountains that contain the North Horn Formation. Named after North Horn Mountain, near Castle Dale, this formation in Emery County contain numerousCretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

- and Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

-era fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s, microfossils

A microfossil is a fossil that is generally between 0.001 mm and 1 mm in size, the visual study of which requires the use of light or electron microscopy. A fossil which can be studied with the naked eye or low-powered magnification, ...

and palynomorph

Palynology is the "study of dust" (from grc-gre, παλύνω, palynō, "strew, sprinkle" and '' -logy'') or of "particles that are strewn". A classic palynologist analyses particulate samples collected from the air, from water, or from deposit ...

s. Flagstaff Peak, north of Emery, has abundant dinosaur bone material, prehistoric mammal remains, and petrified dinosaur footprints. The elevation is around 7000

Fremont people, the Old Spanish Trail, and exploration

TheFremont culture

The Fremont culture or Fremont people is a pre-Columbian archaeological culture which received its name from the Fremont River in the U.S. state of Utah, where the culture's sites were discovered by local indigenous peoples like the Navajo and Ute ...

or Fremont people is a pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, th ...

archeological culture

An archaeological culture is a recurring assemblage of types of artifacts, buildings and monuments from a specific period and region that may constitute the material culture remains of a particular past human society. The connection between thes ...

who existed in the area from AD 700 to 1300. It was adjacent to, roughly contemporaneous with, but distinctly different from the Ancestral Pueblo peoples

The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi, were an ancient Native American culture that spanned the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, an ...

. The culture received its name from the Fremont River

The Fremont River is a long river in southeastern Utah, United States that flows from the Johnson Valley Reservoir, which is located on the Wasatch Plateau near Fish Lake, southeast through Capitol Reef National Park to the Muddy Creek near Ha ...

, where the first Fremont sites were discovered. The Fremont River in Utah flows from the Johnson Valley Reservoir near Fish Lake east through Capitol Reef National Park

Capitol Reef National Park is an American national park in south-central Utah. The park is approximately long on its northsouth axis and just wide on average. The park was established in 1971 to preserve of desert landscape and is open all ye ...

to Muddy Creek, whose headwaters begin just north of Emery.

metate

A metate (or mealing stone) is a type or variety of quern, a ground stone tool used for processing grain and seeds. In traditional Mesoamerican cultures, metates are typically used by women who would grind nixtamalized maize and other organic ma ...

s (millingstones), and weaponry have been found along Muddy and Ivie creeks. Coil pottery, which is most often used to identify archaeological sites as Fremont, is not very different from that made by other Southwestern groups, nor are its vessel forms and designs distinct. What distinguishes Fremont pottery from other ceramic types is the material from which it is constructed. Variations in temper, the granular rock or sand added to wet clay to ensure even drying and to prevent cracking, have been used to identify five major Fremont ceramic types. They include Snake Valley gray in the southwestern part of the Fremont region, Sevier gray in the central area, the Great Salt Lake gray in the northwestern area, and Uinta and Emery gray in the northeast and southwestern regions. Sevier, Snake Valley, and Emery gray also occur in painted varieties. A unique and beautiful painted bowl form, Ivie Creek black-on-white, is found along either side of the southern Wasatch Plateau

The Wasatch Plateau is a plateau located southeast of the southernmost part of the Wasatch Range in central Utah. It is a part of the Colorado Plateau.

Geography

The plateau has an elevation of and includes an area of . Its highest point in the ...

. In addition to these five major types found at Fremont villages, a variety of locally made pottery wares are found on the fringes of the Fremont region in areas occupied by people who seem to have been principally hunters and gatherers

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

rather than farmers. The Rochester Rock Art Panel west of Emery is a significant rock art panel left by the Fremont People and has been the target of vandalism and relic thieves.

The earliest known entrance into the region known as Castle Valley by Europeans dates back to the Spanish explorers. The oldest names in Emery County are Spanish, not Native American — San Rafael, Sinbad, and probably Castle Valley itself are landmarks of that era when Spanish padres, Spanish American explorers, fur traders, trappers, and frontiersmen followed the Old Spanish Trail through Emery. From about 1776 to the mid-1850s, the Old Spanish Trail came up from Santa Fe, New Mexico

Santa Fe ( ; , Spanish for 'Holy Faith'; tew, Oghá P'o'oge, Tewa for 'white shell water place'; tiw, Hulp'ó'ona, label=Tiwa language, Northern Tiwa; nv, Yootó, Navajo for 'bead + water place') is the capital of the U.S. state of New Mexico. ...

, crossed the Colorado River

The Colorado River ( es, Río Colorado) is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The river drains an expansive, arid drainage basin, watershed that encompasses parts of ...

at Moab

Moab ''Mōáb''; Assyrian: 𒈬𒀪𒁀𒀀𒀀 ''Mu'abâ'', 𒈠𒀪𒁀𒀀𒀀

''Ma'bâ'', 𒈠𒀪𒀊 ''Ma'ab''; Egyptian: 𓈗𓇋𓃀𓅱𓈉 ''Mū'ībū'', name=, group= () is the name of an ancient Levantine kingdom whose territo ...

, then the Green River Green River may refer to:

Rivers

Canada

* Green River (British Columbia), a tributary of the Lillooet River

*Green River, a tributary of the Saint John River, also known by its French name of Rivière Verte

*Green River (Ontario), a tributary of ...

where the city of Green River Green River may refer to:

Rivers

Canada

* Green River (British Columbia), a tributary of the Lillooet River

*Green River, a tributary of the Saint John River, also known by its French name of Rivière Verte

*Green River (Ontario), a tributary of ...

now stands, across the San Rafael desert into Castle Valley, then crossed along the eastern part of the town. This became the established route of the Spanish slave traders who captured indigenous people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

along the route and were selling them as slaves.

A sizable herd of

A sizable herd of wild horse

The wild horse (''Equus ferus'') is a species of the genus ''Equus'', which includes as subspecies the modern domesticated horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') as well as the endangered Przewalski's horse (''Equus ferus przewalskii''). The Europea ...

s is managed east of Emery. These wild horses and burro

The domestic donkey is a hoofed mammal in the family Equidae, the same family as the horse. It derives from the African wild ass, ''Equus africanus'', and may be classified either as a subspecies thereof, ''Equus africanus asinus'', or as a ...

s have occupied the San Rafael Swell

The San Rafael Swell is a large geologic feature located in south-central Utah, United States about west of Green River. The San Rafael Swell, measuring approximately , consists of a giant dome-shaped anticline of sandstone, shale, and limeston ...

area since the beginning of the Old Spanish Trail in the early 19th century. Early travelers would lose animals or have them run off by Indians or rustlers. Many of these animals were headed for California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

to be traded and sold and were of good stock. The herd was also augmented by releasing domestic horses from local ranches. By the early 20th century, wild horse and burro numbers had soared and were captured and sold by local mustang

The mustang is a free-roaming horse of the Western United States, descended from horses brought to the Americas by the Spanish. Mustangs are often referred to as wild horses, but because they are descended from once-domesticated animals, they ...

ers. This continued until the passage of the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971

The Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 (WFRHBA), is an Act of Congress (), signed into law by President Richard M. Nixon on December 18, 1971. The act covered the management, protection and study of "unbranded and unclaimed hors ...

. Since the passage of this act, the horses and burros have been managed under federal law and Bureau of Land Management

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is an agency within the United States Department of the Interior responsible for administering federal lands. Headquartered in Washington DC, and with oversight over , it governs one eighth of the country's la ...

regulation.

In the summer of 1853, Captain John W. Gunnison

John Williams Gunnison (November 11, 1812 – October 26, 1853) was an American military officer and explorer.

Biography

Gunnison was born in Goshen, New Hampshire, in 1812 and attended Hopkinton Academy in Hopkinton, New Hampshire. He grad ...

was sent by the War Department of the United States to explore a railroad route to the Pacific coast. Lt. E. G. Beckwith assisted him. They entered Castle Valley and passed near the town in October 1853. Gunnison described the area as follows: "Except three or four small cottonwood trees, there is not a tree to be seen by the unassisted eye on any part of the horizon. The plain lying between us and the Wasatch Range, one hundred miles to the west, is a series of rocky, parallel chasms, and fantastic sandstone ridges. On the north, Roan Cliffs, ten miles from us, present bare masses miles back, a few scattering cedars may be distinguished with the glass. The surface around is whitened with fields of alkali resembling fields of snow. Unless this interior country possesses undiscovered minerals of great value, it can contribute but the merest trifle towards the maintenance of a railroad through it after it has been constructed."Emery Town Historical Committee, Emery Town (1981)

Settlement

The first settlers to Emery came from

The first settlers to Emery came from Sanpete County, Utah

Sanpete County ( ) is a county in the U.S. state of Utah. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population was 27,822. Its county seat is Manti, and its largest city is Ephraim. The county was created in 1850.

History

The Sanpete Valley may ...

. This is unusually notable as the settlers headed east instead of the west (like most settlers at the time), even if it was over a mountain range. The first attempt at settlement was made at Muddy Creek, a stream following down a wide canyon and eventually emptying into the Dirty Devil River

The Dirty Devil River is an tributary of the Colorado River, located in the U.S. state of Utah. It flows through southern Utah from the confluence of the Fremont River and Muddy Creek before emptying into the Colorado River at Lake Powell.

Cours ...

. The Muddy Creek vegetation included tall grass, sage, greasewood, rabbit brush, tender shad scale or Castle Valley clover, prickly pear cacti, and yucca. Along the creek banks were giant cottonwood trees and patches of huge thorny bushes with long needle-sharp spines called bull berry bushes. These berries, when beaten off onto a canvas, could be dried, made into jams, jellies, or even eaten raw.

Among these early settlers were Charles Johnson, Marenus, and Joseph Lund families. Casper Christensen and Fred Acord also brought their families and began to build cabins and plant crops. Joseph Lund, the first to build a small one-room log cabin with a lean-to, became discouraged and left it for Casper Christensen (this building still survives and has been restored and relocated to This Is the Place Heritage Park

This is the Place Heritage Park is a Utah State Park that is located on the east side of Salt Lake City, Utah, United States, at the foot of the Wasatch Range and near the mouth of Emigration Canyon. A non-profit foundation manages the park. ...

in Salt Lake City). Most travels came by way of Salina Canyon and Spring Canyon, which weren't much more than deer trails. Roads were bad at best and almost impassable most of the time. The modes of travel were by horseback, team, and wagon or on snowshoes in wintertime.

Another company settled farther up the canyon around this same date—families who came from Beaver, Mayfield, and Sterling. They called themselves "The Beaver Brothers". Among these were Dan, Miles, and Samuel Miller, George Collier, Samuel Babbett and others. Some of these became discouraged and left the first year. The Millers moved farther down the lower part of the Muddy Creek canyon. This part has been called Miller's Canyon ever since that time.

Several miles south, on Quitchupah Creek, several families were trying to homestead on land that was more barren than Muddy Creek. In the 1870s, Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

called on several families from Sanpete County to settle on Muddy Creek. Most of the first homes on Muddy Creek were called a dugout. It was a room dug in the side of a hill or the bank of a wash. The front was very crude, sometimes the only door being a blanket hung over the opening, or a rough wooden door, hung with leather hinges. The windows were small openings made in the front wall and covered with heavy greased paper or white canvas. Each had a fireplace in one end, which served for heat, cooking and light. The heat from the fire made the dugout unbearably hot in summer, so then the cooking was done on an open fire outside. The roof of the dugout was made of poles, covered with willows and dirt. These roofs served well in dry weather, as they were warm and kept out the wind. However, they leaked badly in stormy weather. Another great inconvenience of these roofs was the fact that they were a home for snakes, rats, mice and spiders. The floors were usually dirt or sometimes rock.

During the years from 1882 to 1885 quite a number of families moved into the Muddy Creek area. A few of them were Jedediah Knight, Joseph Nielson, Pleasant Minchey, Frank Foote, Charley and Ammon Foote, George Merrick, Oscar Beebe, Orson Davis, Heber C. K. Petty, Sr., Joseph Evans, Rasmus Johnson, Carl Magnus Olsen, Peter Nielson, Peter Hansen, Heber Broderick, Peter Christensen, George A. Whitlock, Peter Victor Bunderson, Rasmus Albrechtsen, Christian A. Larsen, Lafe Allred, Hyrum Strong, Peter Jensen, Isaac Kimball, William George Petty, Niels Jensen, Wiley Payne Allred, Andrew C. Anderson, Stephen Williams and David Pratt. Most of these families were Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

immigrants. By 1885, it was determined that the canyon itself was not wide enough for many farms and that more fertile land lay to the south of the Muddy.

The settling of this land required bringing the waters of Muddy Creek through a tunnel that took nearly three years to dig. With no trained engineering assistance, the settlers made their calculations, started from opposite sides of the hill, dodged numerous cave-ins of the treacherous Mancos shale, maintained the correct level inside the tunnel, and connected both tunnels nearly perfectly.

Log cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a less finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first generation home building by settlers.

Eur ...

s were built as soon as logs could be hauled from the nearby mountains. The logs were smoothed on one side with grooves chopped in each end. They were then placed on top of each other with the smooth side facing inward. Chinks between the logs were filled with mud or clay. Willows were used for lath, nailed to the logs, and plastered with mud. This mud was then rubbed smooth and painted with a whitewash

Whitewash, or calcimine, kalsomine, calsomine, or lime paint is a type of paint made from slaked lime ( calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2) or chalk calcium carbonate, (CaCO3), sometimes known as "whiting". Various other additives are sometimes used ...

of lime. The roofs were made of rough lumber and covered with a layer of straw or brush and then a top layer of dirt. Later the roofs were greatly improved when cedar shingles became available.

The town of Muddy would later change to "Emery", after Governor George W. Emery. However, both names would be synonymously used. Emery has always been an agricultural community. Ranching and farming are their major livelihood. The town would swell in population to have its own school, but after World War II, the population decreased due to a lack of economic opportunities and generally hovered around 300 residents. The discovery of coal south of the town led to several mines being developed and the idea that the town could once again draw in new residents. However, with the decrease in coal prices, production has not required the initiation of new mining operations.

On November 2, 1967, the Last Chance Motel was destroyed by a cone-shaped F2 tornado

The Fujita scale (F-Scale; ), or Fujita–Pearson scale (FPP scale), is a scale for rating tornado intensity, based primarily on the damage tornadoes inflict on human-built structures and vegetation. The official Fujita scale category is determ ...

. Furniture and bedding were thrown hundreds of yards. The tornado occurred at the unusual time of 5:30 am, and no injuries were reported.

Geography and climate

Emery is in western Emery County alongUtah State Route 10

State Route 10 (SR-10) is a State Highway in the U.S. state of Utah. The highway follows a long valley in Eastern Utah between the Wasatch Plateau on the west and the San Rafael Swell on the east.

The highway serves the primary and most active co ...

, which leads northeast to Castle Dale, the county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US st ...

, and southwest to Interstate 70

Interstate 70 (I-70) is a major east–west Interstate Highway System, Interstate Highway in the United States that runs from Interstate 15, I-15 near Cove Fort, Utah, to a park and ride lot just east of Interstate 695 (Maryland), I-695 in ...

.

According to the United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of the ...

, the town has a total area of , all land.

Demographics

As of thecensus

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses incl ...

of 2000, there were 308 people, 123 households, and 89 families residing in the town. The population density

Population density (in agriculture: standing stock or plant density) is a measurement of population per unit land area. It is mostly applied to humans, but sometimes to other living organisms too. It is a key geographical term.Matt RosenberPopul ...

was 253.7 people per square mile (98.3/km2). There were 140 housing units at an average density of 115.3 per square mile (44.7/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.73% White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

, 0.97% Native American, and 1.30% from two or more races. Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to Vic ...

or Latino

Latino or Latinos most often refers to:

* Latino (demonym), a term used in the United States for people with cultural ties to Latin America

* Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States

* The people or cultures of Latin America;

** Latin A ...

of any race were 0.97% of the population.

There were 123 households, out of which 29.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.0% were married couples

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between t ...

living together, 6.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.6% were non-families. 26.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years or older. The average household size was 2.50, and the average family size was 3.03.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 28.9% under 18, 5.8% from 18 to 24, 19.2% from 25 to 44, 24.4% from 45 to 64, and 21.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.7 males. For every 100 females aged 18 and over, there were 97.3 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $40,469, and the median income for a family was $51,875. Males had a median income of $40,104 versus $31,250 for females. The

In the town, the population was spread out, with 28.9% under 18, 5.8% from 18 to 24, 19.2% from 25 to 44, 24.4% from 45 to 64, and 21.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.7 males. For every 100 females aged 18 and over, there were 97.3 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $40,469, and the median income for a family was $51,875. Males had a median income of $40,104 versus $31,250 for females. The per capita income

Per capita income (PCI) or total income measures the average income earned per person in a given area (city, region, country, etc.) in a specified year. It is calculated by dividing the area's total income by its total population.

Per capita i ...

was $17,195. About 12.1% of families and 13.1% of the population were below the poverty line

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for t ...

, including 14.3% of those under eighteen and 19.3% of those 65 or over.

Emery is also the county with the fewest people who believe in climate change (49%)

Notable person

*Clay Christiansen

Clay C. Christiansen (born June 28, 1958) is a retired Major League Baseball pitcher. He played during one season at the major league level for the New York Yankees. He was drafted by the Yankees in the 15th round of the 1980 amateur draft. Chri ...

, composer, famed organist for the Mormon Tabernacle Choir

The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square, formerly known as the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, is an American choir, acting as part of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). It has performed in the Salt Lake Tabernacle for ov ...

See also

*List of cities and towns in Utah

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby union ...

* Emery County Cabin

* Emery LDS Church

References

External links

Emery Town

at Emery County's official website {{authority control Towns in Emery County, Utah Towns in Utah Populated places established in 1882