Elizabethton is a city in, and the

county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US st ...

of

Carter County,

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, United States.

Elizabethton is the historical site of the first independent American government (known as the

Watauga Association

The Watauga Association (sometimes referred to as the Republic of Watauga) was a semi-autonomous government created in 1772 by frontier settlers living along the Watauga River in what is now Elizabethton, Tennessee. Although it lasted only a few ...

, created in 1772) located west of both the

Eastern Continental Divide

The Eastern Continental Divide, Eastern Divide or Appalachian Divide is a hydrographic divide in eastern North America that separates the easterly Atlantic Seaboard watershed from the westerly Gulf of Mexico watershed. The divide nearly span ...

and the original

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

.

The city is also the historical site of the

Transylvania Purchase

The Transylvania Colony, also referred to as the Transylvania Purchase, was a short-lived, extra-legal colony founded in early 1775 by North Carolina land speculator Richard Henderson, who formed and controlled the Transylvania Company. Henders ...

(1775), a major muster site during the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

for both the

Battle of Musgrove Mill

The Battle of Musgrove Mill, August 19, 1780, occurred near a ford of the Enoree River, near the present-day border between Spartanburg, Laurens and Union Counties in South Carolina. During the course of the battle, 200 Patriot militiamen defeate ...

(1780) and the

Battle of Kings Mountain

The Battle of Kings Mountain was a military engagement between Patriot and Loyalist militias in South Carolina during the Southern Campaign of the American Revolutionary War, resulting in a decisive victory for the Patriots. The battle took plac ...

(1780). It was within the

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

ist

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

"

State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin or the State of Frankland)Landrum, refers to the proposed state as "the proposed republic of Franklin; while Wheeler has it as ''Frankland''." In ''That's Not in My American History Boo ...

" territory (1784–1788).

The population of Elizabethton was enumerated at 14,176 during the

2010 census.

Geography

Northeast Tennessee location

Elizabethton is located within the "Tri-Cities" area (encompassed by

Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

,

Johnson City, and

Kingsport) of northeast Tennessee.

Time offset from

Coordinated Universal Time

Coordinated Universal Time or UTC is the primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time. It is within about one second of mean solar time (such as UT1) at 0° longitude (at the IERS Reference Meridian as the currently used ...

(UTC):

UTC-5 (

Eastern Time

The Eastern Time Zone (ET) is a time zone encompassing part or all of 23 states in the eastern part of the United States, parts of eastern Canada, the state of Quintana Roo in Mexico, Panama, Colombia, mainland Ecuador, Peru, and a small port ...

).

According to the

United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of the ...

, the city has a total area of , of which is land and , or 1.62%, is water.

The elevation at

Elizabethton Municipal Airport

Elizabethton Municipal Airport is three miles east of Elizabethton, in Carter County, Tennessee. The National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems for 2011–2015 categorized it as a general aviation airport.

Facilities

The airport covers 96 ...

is ASL (the highest point of elevation in Carter County is at

Roan Mountain with an elevation of ASL), and the airport is located on the eastern side of the city along State Highway 91 Stoney Creek Exit. Elizabethton is also connected to larger commercial, shuttle, and cargo flights out of

Tri-Cities Regional Airport

Tri-Cities Airport (also known as Tri-Cities Airport, TN/VA), is in Blountville, Tennessee, United States. It serves the Tri-Cities, Tennessee, Tri-Cities area (Bristol, Tennessee, Bristol, Kingsport, Tennessee, Kingsport, Johnson City, Tennesse ...

northwest of Johnson City.

Lynn Mountain reaches ASL at the summit (36.350°N, 82.191°W) and is located directly across the

U.S. Highway 19E from the downtown Elizabethton business district.

Elizabethton is bordered on the west by

Johnson City.

Water resources and renewable energy

Spring Water

While most of the Tennessee public water-supply systems withdrawing spring water for their supplies are found in East Tennessee, the Elizabethton municipal water system during 2010 extracted and distributed 5.39 Mgal/d of clean spring water from three springs owned by the city --- a unique local supply of flowing spring water that greatly exceeds the volume of spring water extracted and distributed than any other local water resource system across the entire state of Tennessee.

Doe River

The

Doe River

The Doe River is a tributary of the Watauga River in northeast Tennessee in the United States. The river forms in Carter County near the North Carolina line, just south of Roan Mountain State Park, and flows to Elizabethton.

Hydrography

The D ...

forms in

Carter County, Tennessee

Carter County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2010 census, the population was 57,424. Its county seat is Elizabethton. The county is named in honor of Landon Carter (1760-1800), an early settler active in the "Lo ...

, near the

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

line, just south of

Roan Mountain State Park

Roan Mountain State Park is a Tennessee state park in Carter County, in Northeast Tennessee. It is close to the Tennessee-North Carolina border and near the community of Roan Mountain, Tennessee. Situated in the Blue Ridge of the Appalachian ...

. The river initially flows north and is first paralleled by State Route 143; at the community of

Roan Mountain, Tennessee

Roan Mountain is a census-designated place (CDP) in Carter County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 1,360 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Johnson City Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is a component of the Johnson City&nd ...

, it then turns west and is at this point paralleled by

U.S. Route 19E. The Doe River flows to the east of Fork Mountain; the

Little Doe River

The Little Doe River is a river located in Carter County, Tennessee. It forms from the confluence of Simerly Creek and Tiger Creek near the community of Tiger Valley, and runs in a northerly direction alongside U.S. Route 19E until its termination ...

flows by Fork Mountain to the west.

Below the confluence of the Doe River and the Little Doe River at

Hampton

Hampton may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hampton bioregion, an IBRA biogeographic region in Western Australia

*Hampton, New South Wales

*Hampton, Queensland, a town in the Toowoomba Region

*Hampton, Victoria

Canada

*Hampton, New Brunswick

*Hamp ...

, the Doe River then travels roughly in a northern downstream direction through the Valley Forge community, and is rejoined by U.S. Route 19E. Pushing through a mountain gap just north of Hampton, the volume of the river is amplified by the waters flowing from McCathern Spring.

Further downstream, the Doe River flows by the East Side neighborhood parallel with

Tennessee State Route 67

State Route 67 (SR 67) is a state-maintained highway in northeastern Tennessee, including a four-lane divided highway segments in both Washington County and Carter County, and part of a significant two-lane segment passing over the Butler Brid ...

and then underneath the historic

Elizabethton Covered Bridge, built in 1882 and located within the Elizabethton downtown business district. Connecting 3rd Street and Hattie Avenue, the covered bridge is adjacent to a city park and spans the Doe River. The covered bridge, although now closed to motor traffic, is still open for bicycles and pedestrians.

Most of Elizabethton's downtown is listed on the

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

for its historical and architectural merits. The Elizabethton Historic District contains a variety of properties ranging in age from the late 18th century through the 1930s. The Elizabethton Covered Bridge is an important focal point and a well-known landmark in the state. In addition to the covered bridge, the downtown historic district contains the 1928 Elk Avenue concrete arch bridge, and just a little further downstream on the Doe River, Tennessee State Route 67 passes another similar concrete arch bridge locally known as the Broad Street Bridge.

Elizabethton celebrates in the downtown business area for one week each June with the Elizabethton Covered Bridge Days featuring country and gospel music performances, activities for children, Elk Avenue car club show, and many food and crafts vendors.

Watauga River

Two

Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolina ...

(TVA) reservoirs in Carter County—impounded behind the

Watauga Dam

Watauga Dam is a hydroelectric and flood control dam on the Watauga River in Carter County, in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is owned and operated by the Tennessee Valley Authority, which built the dam in the 1940s as part of efforts to contro ...

(forming

Watauga Lake

Watauga Lake, located east of Elizabethton, Tennessee, is the local name of the Watauga Reservoir created by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) with the 1948 completion of the TVA Watauga Dam.

The Cherokee National Forest surrounds both the Ten ...

)

and the immediately downstream

Wilbur Dam

Wilbur Dam is a hydroelectric dam on the Watauga River in Carter County, in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is one of two dams on the river owned and operated by the Tennessee Valley Authority. The dam impounds Wilbur Lake, which extends for abou ...

[Tennessee Valley Authority – Wilbur Reservoir.](_blank)

/ref>—are located southeast and upstream of Elizabethton on the Watauga River

The Watauga River () is a large stream of western North Carolina and East Tennessee. It is long with its headwaters in Linville Gap to the South Fork Holston River at Boone Lake.

Course

The Watauga River rises from a spring near the base ...

. The Appalachian Trail

The Appalachian Trail (also called the A.T.), is a hiking trail in the Eastern United States, extending almost between Springer Mountain in Georgia and Mount Katahdin in Maine, and passing through 14 states.Gailey, Chris (2006)"Appalachian Tr ...

crosses the Watauga River and the TVA reservation in Carter County to the southeast of Elizabethton.confluence

In geography, a confluence (also: ''conflux'') occurs where two or more flowing bodies of water join to form a single channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main stem); o ...

of the Doe River and the Watauga River. The Doe River flows underneath the historic wooden covered bridge that is located within the Elizabethton downtown business district.

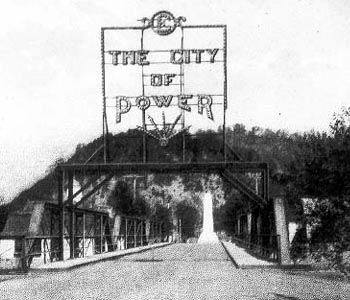

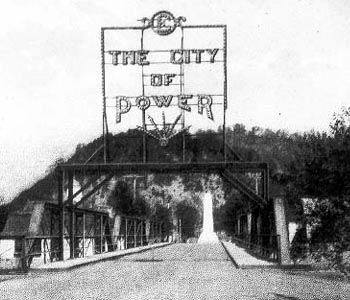

The city of Elizabethton was at one time promoted as "The City of Power", as the town is located just southeast of the Wilbur Dam hydrogeneration site spanning the Watauga River. Construction of Wilbur Dam first began during 1909, and two hydroelectric generating units were online with power production at Wilbur Dam when it was completed in 1912.

Holston Mountain communication towers

Elizabethton lies within a river valley basin mostly surrounded by mountain ridges and significant hills, such as

Elizabethton lies within a river valley basin mostly surrounded by mountain ridges and significant hills, such as Holston Mountain

Holston Mountain is a mountain ridge in Upper East Tennessee and southwest Virginia, in the United States. It is in the Blue Ridge Mountains part of the Appalachian Mountains. Holston Mountain is a very prominent ridge-type mountain in Tennessee ...

, the southern end of which lies just to the northeast. Panhandle Road is located off State Highway 91 in Carter County and ascends Holston Mountain for from the eastern side and ends along the ridge southwest of Holston High Point. During periods of heavy snow and ice, the National Forest Service

The United States Forest Service (USFS) is an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 154 national forests and 20 national grasslands. The Forest Service manages of land. Major divisions of the agency in ...

closes Panhandle Road.

Located near the Cherokee National Forest

The Cherokee National Forest is a United States National Forest located in the U.S. states of Tennessee and North Carolina that was created on June 14, 1920. The forest is maintained and managed by the United States Forest Service. It encompasses ...

boundary and to the left of Panhandle Road is a parking area and foot trail that leads down the slope to the Blue Hole Falls (approximately high). The last of Panhandle Road are filled with washouts, steep drop-offs, and no turnarounds. Vehicle travel on this last section is at the driver's risk.

Early broadcasters in the 1950s and 1960s quickly realized Holston Mountain would be a prime radio-television transmission location because it is the highest visible point that faces most of the major cities in Northeast Tennessee. As a result, the Holston Mountain ridge is the transmitter site for three television stations in the

Early broadcasters in the 1950s and 1960s quickly realized Holston Mountain would be a prime radio-television transmission location because it is the highest visible point that faces most of the major cities in Northeast Tennessee. As a result, the Holston Mountain ridge is the transmitter site for three television stations in the Tri-Cities, Tennessee

The Tri-Cities is the region comprising the cities of Kingsport, Johnson City, and Bristol and the surrounding smaller towns and communities in Northeast Tennessee and Southwest Virginia. All three cities are located in Northeast Tennessee, ...

Television Designated Market Area

A media market, broadcast market, media region, designated market area (DMA), television market area, or simply market is a region where the population can receive the same (or similar) television and radio station offerings, and may also incl ...

. The broadcasting antenna for WCYB-TV

WCYB-TV (channel 5) is a television station licensed to Bristol, Virginia, United States, serving the Tri-Cities area as an affiliate of NBC and The CW. It is one of two commercial television stations in the market that are licensed in Virgin ...

, Channel 5, Bristol, Virginia

Bristol is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,219. It is the twin city of Bristol, Tennessee, just across the state line, which runs down the middle of its main street, State S ...

, is on Rye Patch Knob, with the top of the antenna above ground, above the surrounding valley floor, and above sea level. The single tower the antenna sits on is the highest and tallest man-made structure on the mountain. The television towers for WJHL-TV

WJHL-TV (channel 11) is a television station licensed to Johnson City, Tennessee, United States, serving the Tri-Cities area as an affiliate of CBS and ABC. The station is owned by Nexstar Media Group, and maintains studios on East Main Street ...

, Channel 11, Johnson City, and WKPT-TV

WKPT-TV (channel 19) is a television station licensed to Kingsport, Tennessee, United States, serving the Tri-Cities, Tennessee, Tri-Cities area as an affiliate of Cozi TV. It is owned by Glenwood Communications Corporation alongside low-power ...

, Channel 19, Kingsport, are standing side by side in a common broadcasting antenna farm on the southwest slope of Holston High Point, southwest of Rye Patch Knob. The antenna for WJHL-TV

WJHL-TV (channel 11) is a television station licensed to Johnson City, Tennessee, United States, serving the Tri-Cities area as an affiliate of CBS and ABC. The station is owned by Nexstar Media Group, and maintains studios on East Main Street ...

stands above ground, above the surrounding valley floor, and above sea level. The antenna for WKPT-TV

WKPT-TV (channel 19) is a television station licensed to Kingsport, Tennessee, United States, serving the Tri-Cities, Tennessee, Tri-Cities area as an affiliate of Cozi TV. It is owned by Glenwood Communications Corporation alongside low-power ...

next door stands above ground, also above the valley floor, and above sea level. The stations' digital antennas are also on their respective towers.

Holston Mountain is also the transmitting site for three FM Class C radio stations: WTFM-FM 98.5, Kingsport, Tennessee; WXBQ-FM 96.9, Bristol, Virginia, and WETS-FM 89.5, Johnson City, Tennessee. All three antennas and the backup antennas are located at the antenna farm on the southwest slope of Holston High Point. Also located on the ridge are the antenna for one FM Class C1 radio station, WHCB-FM 91.5, Bristol, Tennessee, located at Rye Patch Knob; one FM Class C2 antenna for radio station WCQR-FM 88.3, Kingsport, Tennessee, and one FM Class D antenna for radio station W214AP-FM 90.7, Johnson City, Tennessee, both transmitting from the antenna farm on the southwest slope of Holston High Point. Various U.S. federal, Tennessee state, Sullivan, Washington and Carter County governmental agencies, along with utility microwave relay

Microwave transmission is the transmission of information by electromagnetic waves with wavelengths in the microwave frequency range of 300MHz to 300GHz(1 m - 1 mm wavelength) of the electromagnetic spectrum. Microwave signals are normally limi ...

stations, also transmit base-to-mobile communications from the Holston High Point antenna farm and Rye Patch Knob.

The Federal Aviation Administration

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the largest transportation agency of the U.S. government and regulates all aspects of civil aviation in the country as well as over surrounding international waters. Its powers include air traffic m ...

maintains a navigational beacon at the Holston Mountain summit.

East Tennessee PBS

WETP-TV (channel 2) is a non-commercial educational television station licensed to Sneedville, Tennessee, United States. It is simulcast full-time over satellite station WKOP-TV (channel 15) in Knoxville. Both are member stations of PBS and joi ...

(or "ETPtv"), while not having a television repeater station serving the immediate area, broadcasts programming on two different over-the-air digital channels that can be received and viewed at higher hilltop elevations in Elizabethton. In early 2009, ETPtv became one of the first stations in East Tennessee to broadcast a digital high definition signal 24 hours a day.

Climate

Connection with Interstate Highway System

The closest Interstate Highway is I-26 in Johnson City. To reach Elizabethton, drivers take Exit 24 and head east on U.S. Route 321 and Tennessee State Route 67

State Route 67 (SR 67) is a state-maintained highway in northeastern Tennessee, including a four-lane divided highway segments in both Washington County and Carter County, and part of a significant two-lane segment passing over the Butler Brid ...

.

Demographics

2020 census

As of the 2020 United States census

The United States census of 2020 was the twenty-fourth decennial United States census. Census Day, the reference day used for the census, was April 1, 2020. Other than a pilot study during the 2000 census, this was the first U.S. census to of ...

, there were 14,546 people, 5,448 households, and 3,301 families residing in the city.

2000 census

As of the census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses incl ...

of 2000, there were 13,372 people, 5,454 households, and 3,512 families residing in the city. The population density

Population density (in agriculture: standing stock or plant density) is a measurement of population per unit land area. It is mostly applied to humans, but sometimes to other living organisms too. It is a key geographical term.Matt RosenberPopul ...

was 1,459.3 people per square mile (563.6/km2). There were 5,964 housing units at an average density of 650.9 per square mile (251.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 95.30% White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

, 2.47% African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

, 0.16% Native American, 0.55% Asian

Asian may refer to:

* Items from or related to the continent of Asia:

** Asian people, people in or descending from Asia

** Asian culture, the culture of the people from Asia

** Asian cuisine, food based on the style of food of the people from Asi ...

, 0.01% Pacific Islander

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the list of islands in the Pacific Ocean, Pacific Islands. As an ethnic group, ethnic/race (human categorization), racial term, it is used to describe the original p ...

, 0.49% from other races

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* ''The Other'' (1930 film), a ...

, and 1.02% from two or more races. Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to Vic ...

or Latino

Latino or Latinos most often refers to:

* Latino (demonym), a term used in the United States for people with cultural ties to Latin America

* Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States

* The people or cultures of Latin America;

** Latin A ...

of any race were 1.18% of the population.

There were 5,454 households, out of which 26.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.6% were married couples

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between t ...

living together, 14.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.6% were non-families. 32.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.24 and the average family size was 2.82.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 20.5% under the age of 18, 10.8% from 18 to 24, 24.5% from 25 to 44, 23.1% from 45 to 64, and 21.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 76.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $25,909, and the median income for a family was $33,333. Males had a median income of $26,890 versus $20,190 for females. The per capita income

Per capita income (PCI) or total income measures the average income earned per person in a given area (city, region, country, etc.) in a specified year. It is calculated by dividing the area's total income by its total population.

Per capita i ...

for the city was $14,578. About 15.2% of families and 19.4% of the population were below the poverty line

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for t ...

, including 29.8% of those under age 18 and 16.1% of those age 65 or over.

History

Native American inhabitants

The area that is now Tennessee was first settled by Paleo-Indians nearly 11,000 years ago. The names of the cultural groups that inhabited the area between first settlement and the time of European contact are unknown, but several distinct cultural phases have been named by archaeologists, including Archaic, Woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

, and Mississippian. Chiefdoms of the Mississippian culture preceded the historic Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands[Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...]

migration into the river's headwaters and lower areas in the eastern part of what became the state.

When Spanish explorers

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

first visited Tennessee, led by Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

in 1539–43, it was inhabited by tribes of Muscogee and Yuchi

The Yuchi people, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native American tribe based in Oklahoma.

In the 16th century, Yuchi people lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee. In the late 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, G ...

people. Possibly because of European diseases devastating the Native tribes, which would have left a population vacuum, and also from expanding European settlement in the north, the Cherokee migrated south through the mountains from the area that is now Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. They occupied a homeland incorporating also western North and South Carolina, northeastern Georgia and Alabama.

As European-American

European Americans (also referred to as Euro-Americans) are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent Eu ...

settler

A settler is a person who has human migration, migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a ...

s expanded through the Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

, they came into armed conflict and forcibly displaced native populations over time to the south and west. The rising states kept up the pressure against Native Americans, as they were eager for their lands. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

in 1830, and the United States military enforced the removal of nearly all Muscogee and Yuchi peoples, the Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as ...

, Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

and Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

. The latter were the last holdouts but, from 1838 to 1839, nearly 17,000 Cherokee were forced to walk overland from "emigration depots" in Alabama and Eastern Tennessee, such as Fort Cass

Fort Cass was a fort located on the Hiwassee River in present-day Charleston, Tennessee, that served as the military operational headquarters for the entire Cherokee removal, an forced migration of the Cherokee known as the Trail of Tears from the ...

, to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

west of Arkansas. (They were transported by boat across the Mississippi River.) This came to be known as the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

, as an estimated 4,000 Cherokees died along the way.

Colonial settlement

In 1769, a young James Robertson accompanied explorer

In 1769, a young James Robertson accompanied explorer Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

on his third expedition to lands beyond the Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range (; also spelled Alleghany or Allegany), informally the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada and posed a significant barrier to land travel in less devel ...

. The party discovered the "Watauga Old Fields" (lands previously cultivated by generations of Native Americans) along the Watauga River

The Watauga River () is a large stream of western North Carolina and East Tennessee. It is long with its headwaters in Linville Gap to the South Fork Holston River at Boone Lake.

Course

The Watauga River rises from a spring near the base ...

valley at present-day Elizabethton, which Robertson planted with corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

while Boone continued on to Kentucky. By 1769 Boone had formed an association with North Carolina promoter and judge Richard Henderson with a goal to purchase and settle a vast tract of Cherokee lands in present-day Middle Tennessee and Kentucky, and Boone later relocated his family to the Watauga Settlement sometime during the spring of 1771.

After the Battle of Alamance

The Battle of Alamance, which took place on May 16, 1771, was the final battle of the Regulator Movement, a rebellion in Province of North Carolina, colonial North Carolina over issues of taxation and local control, considered by some to be the ...

in 1771, many North Carolinians refused to take the new oath of allegiance to the Royal Crown and withdrew from the province. Instead of taking their new oath of allegiance, James Robertson led a group of some twelve or thirteen families involved with the Regulator movement

The Regulator Movement, also known as the Regulator Insurrection, War of Regulation, and War of the Regulation, was an uprising in Province of North Carolina, Provincial North Carolina from 1766 to 1771 in which citizens took up arms against colo ...

from near where present-day Raleigh, North Carolina

Raleigh (; ) is the capital city of the state of North Carolina and the List of North Carolina county seats, seat of Wake County, North Carolina, Wake County in the United States. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, second-most ...

, now stands. In 1772, Robertson and the pioneers who had settled in Northeast Tennessee (along the Watauga River, the Doe River

The Doe River is a tributary of the Watauga River in northeast Tennessee in the United States. The river forms in Carter County near the North Carolina line, just south of Roan Mountain State Park, and flows to Elizabethton.

Hydrography

The D ...

, the Holston River

The Holston River is a river that flows from Kingsport, Tennessee, to Knoxville, Tennessee. Along with its three major forks (North Fork, Middle Fork and South Fork), it comprises a major river system that drains much of northeastern Tennessee ...

, and the Nolichucky River

The Nolichucky River is a river that flows through Western North Carolina and East Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Traversing the Pisgah National Forest and the Cherokee National Forest in the Blue Ridge Mountains, the river's wate ...

) met at Sycamore Shoals

The Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River, usually shortened to Sycamore Shoals, is a rocky stretch of river rapids along the Watauga River in Elizabethton, Tennessee. Archeological excavations have found Native Americans lived near the shoals s ...

to establish an independent regional government known as the Watauga Association

The Watauga Association (sometimes referred to as the Republic of Watauga) was a semi-autonomous government created in 1772 by frontier settlers living along the Watauga River in what is now Elizabethton, Tennessee. Although it lasted only a few ...

.

John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

, the future first governor of the State of Tennessee, first visited the Holston settlement and surrounding areas in present-day northeast Tennessee during 1771, bringing items to trade with settlers from his merchandising business in Middletown, Virginia

Middletown is a town in Frederick County, Virginia, United States, in the northern Shenandoah Valley. The population was 1,265 at the 2010 census, up from 1,015 at the 2000 census.

History

Middletown was chartered on May 4, 1796. Some of the f ...

. Sevier later returned to the area in 1772, where he witnessed a horse race at "the Watauga Old Fields, on Doe River; near its junction with the Watauga."

However, in 1772, surveyors placed the land officially within the domain of the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

tribe, who required negotiation of a lease with the settlers. Tragedy struck as the lease was being celebrated, when a Cherokee warrior was murdered by a white man. James Robertson's skillful diplomacy made peace with the irate Native Americans, who threatened to expel the settlers by force if necessary.

All of present-day Tennessee was once recognized as one single North Carolina county: Washington County, North Carolina

Washington County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 11,003. Its county seat is Plymouth. The county was formed in 1799 from the western third of Tyrrell County. It was named fo ...

. Created in 1777 from the western areas of Burke

Burke is an Anglo-Norman Irish surname, deriving from the ancient Anglo-Norman and Hiberno-Norman noble dynasty, the House of Burgh. In Ireland, the descendants of William de Burgh (–1206) had the surname ''de Burgh'' which was gaelicised ...

and Wilkes counties in North Carolina, Washington County had as its precursor the Washington District of 1775–76, which was the first political entity named for the Commander-in-Chief of American forces in the Revolution.[ "Lost Counties of Tennessee.]

American Revolutionary War

Transylvania Purchase at Sycamore Shoals

Elizabethton (at

Elizabethton (at Sycamore Shoals

The Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River, usually shortened to Sycamore Shoals, is a rocky stretch of river rapids along the Watauga River in Elizabethton, Tennessee. Archeological excavations have found Native Americans lived near the shoals s ...

) was the Fort Watauga

Fort Watauga, more properly Fort Caswell, was an American Revolutionary War fort that once stood at the Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River in what is now Elizabethton, Tennessee. The fort was originally built in 1775–1776 by the area's front ...

site of the Transylvania Purchase

The Transylvania Colony, also referred to as the Transylvania Purchase, was a short-lived, extra-legal colony founded in early 1775 by North Carolina land speculator Richard Henderson, who formed and controlled the Transylvania Company. Henders ...

. In March 1775, land speculator and North Carolina judge Richard Henderson met with more than 1,200 Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

s at Sycamore Shoals, including Cherokee leaders such as Attacullaculla

Attakullakulla (Cherokee”Tsalagi”, (ᎠᏔᎫᎧᎷ) ''Atagukalu''; also spelled Attacullaculla and often called Little Carpenter by the English) (c. 1715 – c. 1777) was an influential Cherokee leader and the tribe's First Belove ...

, Oconostota

Oconostota (c. 1710–1783) was a Cherokee ''skiagusta'' (war chief) of Chota, which was for nearly four decades the primary town in the Overhill territory, and within what is now Monroe County, Tennessee. He served as the First Beloved Man of Ch ...

, and Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe (ᏥᏳ ᎦᏅᏏᏂ, pronounced ''Tsiyu Gansini'', "he is dragging his canoe") (c. 1738 – February 29, 1792) was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee warriors who resisted colonists and United States settlers in the ...

. In the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

(also known as the Treaty of Watauga), Henderson purchased all the land lying between the Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a major waterway of the Southern United States. The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 8, 2011 river drains almost of southern Kentucky and ...

, the Cumberland Mountains

The Cumberland Mountains are a mountain range in the southeastern section of the Appalachian Mountains. They are located in western Virginia, southwestern West Virginia, the eastern edges of Kentucky, and eastern middle Tennessee, including the ...

, and the Kentucky River

The Kentucky River is a tributary of the Ohio River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 13, 2011 in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. Commonwealth of Kentuc ...

, and situated south of the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

. The land thus delineated, 20 million acres (81,000 km2), encompassed an area half as large as the present state of Kentucky. Henderson's purchase was in violation of North Carolina and Virginia law, as well as the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

, which prohibited private purchase of American Indian land. Henderson may have mistakenly believed that a newer British legal opinion had made such land purchases legal.

Before the Sycamore Shoals treaty, Henderson had hired Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

, an experienced hunter who had explored Kentucky, to travel to the Cherokee towns and inform them of the upcoming negotiations. Afterwards, Boone was hired to blaze what became known as the Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was one of two principal routes used by colonial and early national era settlers to reach Kentucky from the East. Although this road goes through the Cumberland Gap into southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, the other (mo ...

, which went through the Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its rol ...

and into central Kentucky. Along with a party of about thirty workers, Boone marked a path to the Kentucky River

The Kentucky River is a tributary of the Ohio River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 13, 2011 in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. Commonwealth of Kentuc ...

, where he established Boonesborough Boonesborough or Boonesboro may refer to a place in the United States:

* Boonesboro, Iowa, now part of Boone, Iowa

*Boonesborough, Kentucky

*Boonesboro, Missouri

Boonesboro is a community in Howard County, Missouri, United States. It is located o ...

(near present-day Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, Fayette County. By population, it is the List of cities in Kentucky, second-largest city in Kentucky and List of United States cities by popul ...

), which was intended to be the capital of Transylvania. Other settlements, notably Harrodsburg

Harrodsburg is a home rule-class city in Mercer County, Kentucky, United States. It is the seat of its county. The population was 9,064 at the 2020 census.

Although Harrodsburg was formally established by the House of Burgesses after Boonesbo ...

, were also established at this time. Many of these settlers had come to Kentucky on their own initiative, and did not recognize Transylvania's authority. A Daniel Boone Trail historical marker is found just outside the downtown Elizabethton business district.

July 1776 Dragging Canoe Attacks

Early during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, Fort Watauga at Sycamore Shoals

The Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River, usually shortened to Sycamore Shoals, is a rocky stretch of river rapids along the Watauga River in Elizabethton, Tennessee. Archeological excavations have found Native Americans lived near the shoals s ...

was attacked in 1776 by Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe (ᏥᏳ ᎦᏅᏏᏂ, pronounced ''Tsiyu Gansini'', "he is dragging his canoe") (c. 1738 – February 29, 1792) was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee warriors who resisted colonists and United States settlers in the ...

and his warring faction of Cherokees opposed to the Transylvania Purchase (warring Cherokees also referred to by settlers as the Chickamauga Chickamauga may refer to:

Entertainment

* "Chickamauga", an 1889 short story by American author Ambrose Bierce

* "Chickamauga", a 1937 short story by Thomas Wolfe

* "Chickamauga", a song by Uncle Tupelo from their 1993 album ''Anodyne (album), Ano ...

), Cols. John Sevier and James Robertson are named as being among the defenders of the stockade fort along the Watauga River.

Wataugans' Settlement of Middle Tennessee

During the spring of 1779, James Robertson and a small group of Watauga settlers, acting upon the survey of Henderson's Transylvania Purchase, traveled west overland to select a site for a new settlement along the Cumberland River known as the French Lick

French Lick is a town in French Lick Township, Orange County, Indiana. The population was 1,807 at the time of the 2010 census. In November 2006, the French Lick Resort Casino, the state's tenth casino in the modern legalized era, opened, drawing ...

(at present day Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and the ...

). Later that same year, Robertson would return to the French Lick with a group of men to construct temporary shelters for their friends and relatives from the Watauga Settlement, who would eventually arrive at their new French Lick settlement on Christmas Day and drive their cattle across a frozen Cumberland River. A fort built by James Robertson and other settlers from the Watauga Settlement atop a bluff along the Cumberland River was named Fort Nashborough in honor of Francis Nash, who had fought alongside Robertson during the 1771 Battle of Alamance.

Overmountain Men Muster for the Battle of Kings Mountain

The Overmountain Men serving under Col. Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic an ...

(who years earlier had worked as a surveyor for the Transylvania Company) and other patriot forces engaged and defeated a larger force of British Loyalists on August 19, 1780 at the Battle of Musgrove Mill

The Battle of Musgrove Mill, August 19, 1780, occurred near a ford of the Enoree River, near the present-day border between Spartanburg, Laurens and Union Counties in South Carolina. During the course of the battle, 200 Patriot militiamen defeate ...

near present-day Clinton, South Carolina

Clinton is a city in Laurens County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 8,490 as of the 2010 census. It is part of the Greenville– Mauldin– Easley Metropolitan Statistical Area. Clinton is the home of Presbyterian Col ...

. Fort Watauga later served as the September 26, 1780,[U.S. National Park Service.](_blank)

/ref> staging area for a much larger contingent of some 1,100 Overmountain Men

The Overmountain Men were American frontiersmen from west of the Blue Ridge Mountains which are the leading edge of the Appalachian Mountains, who took part in the American Revolutionary War. While they were present at multiple engagements in th ...

who were preparing to trek over the Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States, and extends 550 miles southwest from southern Pennsylvania through Maryland, West Virgin ...

at Roan Mountain to engage, and subsequently defeat, the British Army Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

forces at the Battle of Kings Mountain

The Battle of Kings Mountain was a military engagement between Patriot and Loyalist militias in South Carolina during the Southern Campaign of the American Revolutionary War, resulting in a decisive victory for the Patriots. The battle took plac ...

in rural York County, South Carolina

York County is a County (United States), county in the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2010 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 282,090, making it the seventh most populous county in the state. Its county seat is the cit ...

, south of the present-day town of Kings Mountain, North Carolina

Kings Mountain is a small suburban city within the Charlotte metropolitan area in Cleveland and Gaston counties, North Carolina, United States. Most of the city is in Cleveland County, with a small eastern portion in Gaston County. The popul ...

.

Prior to the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

very little gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). ...

had been made in the colonies, and most was imported from Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

.[Brown, ''The Big Bang: A History of Explosives'', p?] In October 1777, the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremacy ...

banned the importation of gunpowder into the American colonies. In preparation for the overmountain march, five hundred pounds of black powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

was manufactured for the Overmountain Men by Mary Patton and her husband at their Gap Creek powder mill. The Overmountain Men stored the Patton black powder on the rainy first night of their march in a dry cave known as the Shelving Rock that is located near Roan Mountain State Park

Roan Mountain State Park is a Tennessee state park in Carter County, in Northeast Tennessee. It is close to the Tennessee-North Carolina border and near the community of Roan Mountain, Tennessee. Situated in the Blue Ridge of the Appalachian ...

at present-day Roan Mountain, Tennessee

Roan Mountain is a census-designated place (CDP) in Carter County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 1,360 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Johnson City Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is a component of the Johnson City&nd ...

.Battle of Cowpens

The Battle of Cowpens was an engagement during the American Revolutionary War fought on January 17, 1781 near the town of Cowpens, South Carolina, between U.S. forces under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan and British forces under Lieutenant Colo ...

in South Carolina.

John Carter, Landon Carter, and the Carter Mansion

Landon Carter was the son of early Carter County settler John Carter. John Carter's circa 1780 white frame home, known as the Carter Mansion, now serves as a tourist attraction and is part of Sycamore Shoals State Park

Sycamore Shoals State Historic Area is a state park located in Elizabethton, in the U.S. state of Tennessee. The park consists of situated along the Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River, a National Historic Landmark where a series of events crit ...

, although it is not at the park's main location. The oldest frame house in Tennessee, this former frontier plantation home is located on Broad Street Extension on the eastern side of town above the banks of the Watauga River. The property also contains a small Carter family cemetery. A landscape painting of a Virginia plantation that was discovered beneath layers of ancient paint covering the wall surface above a fireplace mantle suggests that John Carter may have been an illegitimate son of the wealthy Virginia plantation owner Robert "King" Carter

Robert "King" Carter (4 August 1663 – 4 August 1732) was a merchant, planter and powerful politician in colonial Virginia. Born in Lancaster County, Carter eventually became one of the richest men in the Thirteen Colonies. As President of t ...

and half-brother to Virginia plantation owner Landon Carter

Col. Landon Carter, I (August 18, 1710 – December 22, 1778) was an American planter and burgess for Richmond County, Virginia. Although one of the most popular patriotic writers and pamphleters of pre-Revolutionary and Revolutionary-era Vir ...

.

Tiptonville and the Battle of Franklin feud

Carter County was previously named "Wayne County" while briefly within the defeated State of Franklin (along with present-day

Carter County was previously named "Wayne County" while briefly within the defeated State of Franklin (along with present-day Johnson County, Tennessee

Johnson County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2010 census, the population was 18,244. Its county seat is Mountain City. It is the state's northeasternmost county, sharing borders with Virginia and North Carolina. ...

, 1784–88).John Tipton

John Tipton (August 14, 1786 – April 5, 1839) was from Tennessee and became a farmer in Indiana; an officer in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, and veteran officer of the War of 1812, in which he reached the rank of Brigadier General; and pol ...

, had deeded the land on which the town Tiptonville was established on the banks of the Doe River near its confluence with the Watauga River then within Wayne County.

The February 1788 Battle of Franklin was fought between those aligned with Col. John Tipton and loyal to the area remaining within the authority of the State of North Carolina and the United States and the opposition aligned with Col. John Sevier who were seeking secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

from the State of North Carolina as an independent State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin or the State of Frankland)Landrum, refers to the proposed state as "the proposed republic of Franklin; while Wheeler has it as ''Frankland''." In ''That's Not in My American History Boo ...

under Spanish rule. The Battle of Franklin took place on a farm owned by Col. John Tipton (now known as the Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site

Tipton-Haynes State Historic Site, known also as Tipton-Haynes House, is a Tennessee State Historic Site located at 2620 South Roan Street in Johnson City, Tennessee. It includes a house originally built in 1784 by Colonel John Tipton, and 10 oth ...

) within the southern section of present-day Johnson City, Tennessee

Johnson City is a city in Washington, Carter, and Sullivan counties in the U.S. state of Tennessee, mostly in Washington County. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 71,046, making it the eighth largest city in Tennessee. John ...

.

Col. John Tipton would also later help to lead the effort of toward having Tennessee being admitted as the sixteenth state into the United States of America during 1796.

Following the 1796 admittance of the State of Tennessee into the United States of America, Wayne County was renamed named as Carter County by the losers of the Battle of Franklin in honor of Landon Carter, who served both as Chairman of the Court of the Watauga Settlement (as defined by the articles of the Watauga Petition) and as Speaker of the defunct State of Franklin Senate.

Previously named "Tiptonville" in honor of Samuel Tipton while within the State of Franklin, the town was as the county seat of the newly minted Tennessee county of Carter was, likewise, renamed as "Elizabethton" by Landon Carter and David McNabb (who were members of a state committee to officially name the area that was appointed by the Tennessee General Assembly in 1796 to locate and name the county seat of Carter County) after their wives, Elizabeth MacLin Carter and Elizabeth McNabb.

The gravesite of Samuel Tipton, "Founder of Elizabethton", is located at the Green Hill Cemetery, found on the crest of West Mill Street and overlooking northeast by north

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

toward the historic site of Fort Caswell (this location as recorded in the unpublished John Sevier notes of Wisconsin historian Lyman C. Draper, and now more popularly known as Fort Watauga) and the Watauga River.

American Civil War

On the recommendation of Military Governor of Tennessee

On the recommendation of Military Governor of Tennessee Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, U.S. naval officer Samuel Powhattan (S.P.) Carter was promoted to the brevet rank

In many of the world's military establishments, a brevet ( or ) was a warrant giving a commissioned officer a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct but may not confer the authority, precedence, or pay of real rank. ...

of brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

and assigned by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

to engage cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

based in Kentucky against Confederate-held railroad lines and bridges in East Tennessee during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

.

In early 1861, after receiving a letter from Carter assuring his loyalty to the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

should a civil war break out, Tennessee Governor Andrew Johnson used his influence in the United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army, a ...

for Carter to organize and train militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

within East Tennessee. After leading successful cavalry operations at the Battle of Mill Springs

The Battle of Mill Springs, also known as the Battle of Fishing Creek in Confederate terminology, and the Battle of Logan's Cross Roads in Union terminology, was fought in Wayne and Pulaski counties, near current Nancy, Kentucky, on January 1 ...

on January 19, 1862, Carter accepted a commission as Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

of volunteers in May and later continued leading operations at the Battle of Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its rol ...

in June as well as raids against Holston, Carter's Station, and Jonesville in December, in support of General William S. Rosecrans

William Starke Rosecrans (September 6, 1819March 11, 1898) was an American inventor, coal-oil company executive, diplomat, politician, and U.S. Army officer. He gained fame for his role as a Union general during the American Civil War. He was t ...

' attack on Murfreesboro.

Carter's younger brother, William B. Carter (1820−1902), planned and coordinated the so-called East Tennessee bridge burnings in 1861. On the night of November 8 of that year, Carter's pro-Union conspirators destroyed five railroad bridges across Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

-occupied East Tennessee. Daniel Stover, a son-in-law of Andrew Johnson who lived near Elizabethton in the Siam community, led the party that destroyed the bridge at Union Depot (modern Bluff City). Confederate authorities placed much of East Tennessee under martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

as a result of the bridge-burning incident.

In July 1863, Carter was placed in command of the XXIII Corps cavalry division and would continue campaigning across Tennessee throughout the year. By 1865, Carter was in North Carolina and commanding the left wing of the Union forces at the Battle of Kingston

The Battle of Kingston (November 24, 1863) saw Major General Joseph Wheeler with two divisions of Confederate States Army, Confederate cavalry attempt to overcome the Union (American Civil War), Union garrison of Kingston, Tennessee, led by Colone ...

. He was promoted to Brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

of Volunteers, briefly commanding the XXIII Corps before being mustered out of volunteer service in January 1866.

While Carter was serving in the Union Army, the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

promoted him to lieutenant commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

in 1863, then to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

in 1865. A Tennessee Historical Marker located on West Elk Avenue in front of the S.P. Carter Mansion in downtown Elizabethton commemorates his life and naval career.

The Veterans' Monument in downtown Elizabethton was originally constructed and dedicated in 1912 to "the memory of the old soldiers of Carter County since the days of the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

." It is in the form of an obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by Anc ...

, constructed primarily from river rock collected from the nearby Doe River, guarded by two short Civil War field cannon.

Railroad history

During the early 20th century, Elizabethton became a rail hub, served by three different railroad companies.

Beginning in the 1880s, the narrow-gauge

A narrow-gauge railway (narrow-gauge railroad in the US) is a railway with a track gauge narrower than standard . Most narrow-gauge railways are between and .

Since narrow-gauge railways are usually built with tighter curves, smaller structur ...

engine known as the "Tweetsie" ran on the East Tennessee and Western North Carolina Railroad

The East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad , affectionately called the "Tweetsie" as a verbal acronym of its initials (ET&WNC) but also in reference to the sound of its steam whistles, was a primarily narrow gauge railroad established ...

(ET&WNC) from Johnson City, passing through Elizabethton before climbing into the Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States, and extends 550 miles southwest from southern Pennsylvania through Maryland, West Virgin ...

, eventually connecting to Boone, North Carolina

Boone is a town in and the county seat of Watauga County, North Carolina, United States. Located in the Blue Ridge Mountains of western North Carolina, Boone is the home of Appalachian State University and the headquarters for the disaster a ...

, in 1916.

In 1927, the portion of the ET&WNC railroad from Johnson City to Elizabethton was converted to standard gauge

A standard-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge of . The standard gauge is also called Stephenson gauge (after George Stephenson), International gauge, UIC gauge, uniform gauge, normal gauge and European gauge in Europe, and SGR in Ea ...

in order to more efficiently serve the NARC and Bemberg Rayon Plants.

The narrow-gauge portion of the ET&WNC ceased operations in 1950 and was subsequently abandoned, though the standard-gauge portion of the line from Johnson City to Elizabethton continued to operate until 2003 as the East Tennessee Railway

The East Tennessee Railway, L.P. is a short line railroad connecting CSX Transportation and the Norfolk Southern Railway in Johnson City, Tennessee. Since 2005, the railroad has been owned by Genesee and Wyoming, an international operator of s ...

. The railroad's dormant track has been removed, pending negotiations between Elizabethton and Johnson City to establish a walking and bike path.

One of the ET&WNC's narrow-gauge steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, oil or, rarely, wood) to heat water in the locomot ...

s (Engine #12) is still in existence, operating at the "Tweetsie Railroad

Tweetsie Railroad is a family-oriented heritage railroad and Wild West amusement park located between Boone and Blowing Rock, North Carolina, United States. The centerpiece of the park is a ride on a train pulled by one of Tweetsie Railroad's t ...

" theme park

An amusement park is a park that features various attractions, such as rides and games, as well as other events for entertainment purposes. A theme park is a type of amusement park that bases its structures and attractions around a central ...

at nearby Blowing Rock, North Carolina

Blowing Rock is a town in Watauga and Caldwell counties in the U.S. state of North Carolina. The population was 1,397 at the 2021 census.

The Caldwell County portion of Blowing Rock is part of the Hickory–Lenoir– Morganton Metropolita ...

.

The Southern Railway operated a branch line

A branch line is a phrase used in railway terminology to denote a secondary railway line which branches off a more important through route, usually a main line. A very short branch line may be called a spur line.

Industrial spur

An industri ...

into Elizabethton until the flood of 1940. It connected with the ET&WNC at a small railroad yard

A rail yard, railway yard, railroad yard (US) or simply yard, is a series of tracks in a rail network for storing, sorting, or loading and unloading rail vehicles and locomotives. Yards have many tracks in parallel for keeping rolling stock or u ...

near the confluence of the Watauga River

The Watauga River () is a large stream of western North Carolina and East Tennessee. It is long with its headwaters in Linville Gap to the South Fork Holston River at Boone Lake.

Course

The Watauga River rises from a spring near the base ...

and the Doe River

The Doe River is a tributary of the Watauga River in northeast Tennessee in the United States. The river forms in Carter County near the North Carolina line, just south of Roan Mountain State Park, and flows to Elizabethton.

Hydrography

The D ...

.

In the 1910s and 1920s, another small railroad, the Laurel Fork Railway The Laurel Fork Railway was a small, standard-gauge logging railroad that operated entirely in Carter County, Tennessee from 1912 to 1927. Built by the Pittsburgh Lumber Company to serve a double-band sawmill at Braemar, in present-day Hampton, Ten ...

, operated out of Elizabethton paralleling the ET&WNC and Doe River to Hampton

Hampton may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hampton bioregion, an IBRA biogeographic region in Western Australia

*Hampton, New South Wales

*Hampton, Queensland, a town in the Toowoomba Region

*Hampton, Victoria

Canada

*Hampton, New Brunswick

*Hamp ...

, where the line split off and ran to a sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes (dimensi ...

near present-day Watauga Lake

Watauga Lake, located east of Elizabethton, Tennessee, is the local name of the Watauga Reservoir created by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) with the 1948 completion of the TVA Watauga Dam.

The Cherokee National Forest surrounds both the Ten ...

.

North American Rayon Corp., American Bemberg Corp., and the 1929 Rayon Plants strikes

Beginning in the late 1920s, German and Dutch business investors established two major rayon

Rayon is a semi-synthetic fiber, made from natural sources of regenerated cellulose, such as wood and related agricultural products. It has the same molecular structure as cellulose. It is also called viscose. Many types and grades of viscose f ...

manufacturing plants (Bemberg and the North American Rayon Corporation) in Elizabethton along the banks of the Watauga River, producing rayon material for both U.S. domestic and export markets.

The Rayon factories were controlled by the German-Dutch Algemene Kunstzijde Unie

Vereinigte Glanzstoff-Fabriken (VGF, United Rayon Factories) was a German manufacturer of artificial fiber founded in 1899 that became one of the leading European producers of rayon.

During the first thirty years VGF cooperated closely with the Br ...

(AKU).

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...