Elizabeth Browning on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (née Moulton-Barrett; 6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was an English poet of the

She was educated at home and tutored by Daniel McSwiney with her oldest brother. She began writing verses at the age of four."Browning, Elizabeth Barrett: Introduction." Jessica Bomarito and Jeffrey W. Hunter (eds). ''Feminism in Literature: A Gale Critical Companion''. Vol. 2: 19th Century, Topics & Authors (A-B). Detroit: Gale, 2005. 467–469. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 December 2014. During the Hope End period, she was an intensely studious, precocious child.Taplin, Gardner B. ''The Life of Elizabeth Browning'' New Haven: Yale University Press (1957). She claimed that at the age of six, she was reading novels, at eight entranced by

She was educated at home and tutored by Daniel McSwiney with her oldest brother. She began writing verses at the age of four."Browning, Elizabeth Barrett: Introduction." Jessica Bomarito and Jeffrey W. Hunter (eds). ''Feminism in Literature: A Gale Critical Companion''. Vol. 2: 19th Century, Topics & Authors (A-B). Detroit: Gale, 2005. 467–469. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 December 2014. During the Hope End period, she was an intensely studious, precocious child.Taplin, Gardner B. ''The Life of Elizabeth Browning'' New Haven: Yale University Press (1957). She claimed that at the age of six, she was reading novels, at eight entranced by  Elizabeth's mother died in 1828, and is buried at St Michael's Church, Ledbury, next to her daughter Mary. Sarah Graham-Clarke, Elizabeth's aunt, helped to care for the children, and she had clashes with Elizabeth's strong will. In 1831, Elizabeth's grandmother, Elizabeth Moulton, died. Following lawsuits and the abolition of slavery, Mr Barrett incurred great financial and investment losses that forced him to sell Hope End. Although the family was never poor, the place was seized, and put up for sale to satisfy creditors. Always secret in his financial dealings, he would not discuss his situation and the family was haunted by the idea that they might have to move to Jamaica.

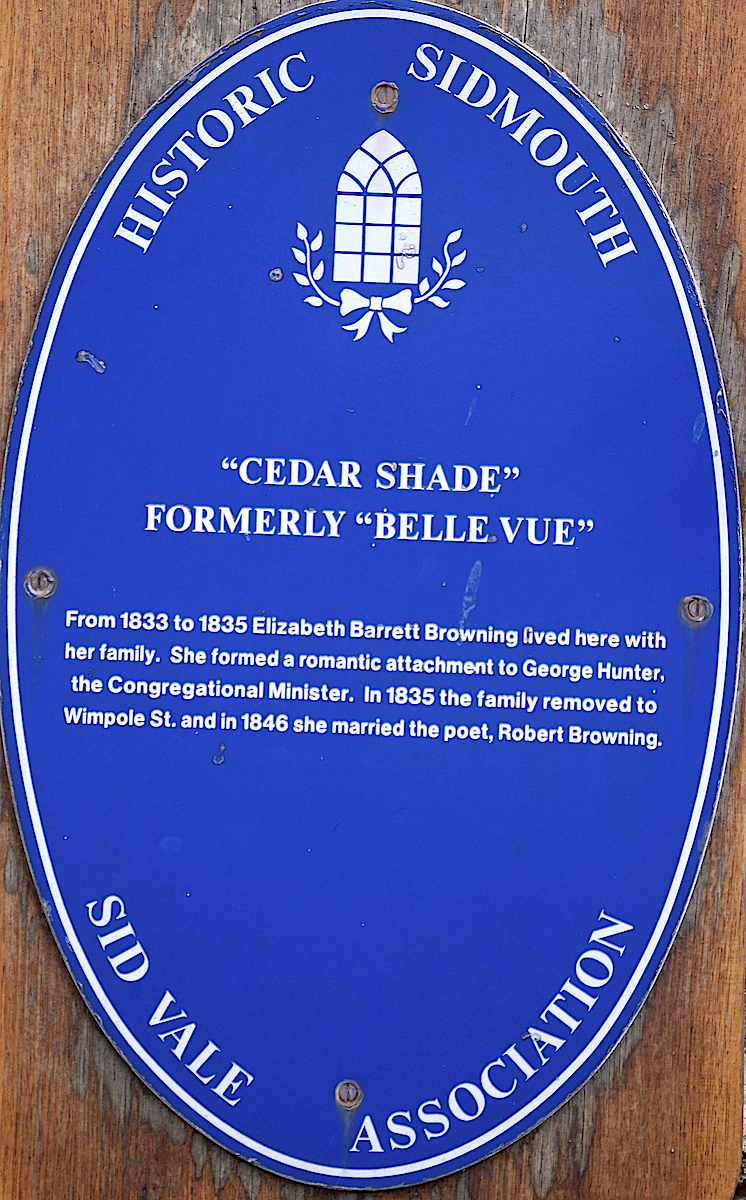

Between 1833 and 1835, she was living with her family at Belle Vue in Sidmouth. The site has now been renamed Cedar Shade and redeveloped. A blue plaque at the entrance to the site attests to this. In 1838, some years after the sale of Hope End, the family settled at 50 Wimpole Street.

During 1837–38, the poet was struck with illness again, with symptoms today suggesting

Elizabeth's mother died in 1828, and is buried at St Michael's Church, Ledbury, next to her daughter Mary. Sarah Graham-Clarke, Elizabeth's aunt, helped to care for the children, and she had clashes with Elizabeth's strong will. In 1831, Elizabeth's grandmother, Elizabeth Moulton, died. Following lawsuits and the abolition of slavery, Mr Barrett incurred great financial and investment losses that forced him to sell Hope End. Although the family was never poor, the place was seized, and put up for sale to satisfy creditors. Always secret in his financial dealings, he would not discuss his situation and the family was haunted by the idea that they might have to move to Jamaica.

Between 1833 and 1835, she was living with her family at Belle Vue in Sidmouth. The site has now been renamed Cedar Shade and redeveloped. A blue plaque at the entrance to the site attests to this. In 1838, some years after the sale of Hope End, the family settled at 50 Wimpole Street.

During 1837–38, the poet was struck with illness again, with symptoms today suggesting

At Wimpole Street, Elizabeth spent most of her time in her upstairs room. Her health began to improve, though she saw few people other than her immediate family. One of those was John Kenyon, a wealthy friend and distant cousin of the family and patron of the arts. She received comfort from a spaniel named Flush, a gift from Mary Mitford. (

At Wimpole Street, Elizabeth spent most of her time in her upstairs room. Her health began to improve, though she saw few people other than her immediate family. One of those was John Kenyon, a wealthy friend and distant cousin of the family and patron of the arts. She received comfort from a spaniel named Flush, a gift from Mary Mitford. (

Her 1844 volume ''Poems'' made her one of the most popular writers in the country, and inspired

Her 1844 volume ''Poems'' made her one of the most popular writers in the country, and inspired  The courtship and marriage between Robert Browning and Elizabeth were carried out secretly, as she knew her father would disapprove. After a private marriage at St Marylebone Parish Church, they honeymooned in Paris before moving, in September 1846, to Italy, which became their home almost continuously until her death. Elizabeth's loyal lady's maid, Elizabeth Wilson, witnessed the marriage and accompanied the couple to Italy.

Mr Barrett disinherited Elizabeth, as he did each of his children who married. Elizabeth had foreseen her father's anger but had not anticipated her brothers' rejection. As Elizabeth had some money of her own, the couple were reasonably comfortable in Italy. The Brownings were well respected, and even famous. Elizabeth grew stronger and in 1849, at the age of 43, between four miscarriages, she gave birth to a son, Robert Wiedeman Barrett Browning, whom they called Pen. Their son later married, but had no legitimate children.

At her husband's insistence, Elizabeth's second edition of ''Poems'' included her love sonnets; as a result, her popularity increased (as did critical regard), and her artistic position was confirmed.

The couple came to know a wide circle of artists and writers including William Makepeace Thackeray, sculptor

The courtship and marriage between Robert Browning and Elizabeth were carried out secretly, as she knew her father would disapprove. After a private marriage at St Marylebone Parish Church, they honeymooned in Paris before moving, in September 1846, to Italy, which became their home almost continuously until her death. Elizabeth's loyal lady's maid, Elizabeth Wilson, witnessed the marriage and accompanied the couple to Italy.

Mr Barrett disinherited Elizabeth, as he did each of his children who married. Elizabeth had foreseen her father's anger but had not anticipated her brothers' rejection. As Elizabeth had some money of her own, the couple were reasonably comfortable in Italy. The Brownings were well respected, and even famous. Elizabeth grew stronger and in 1849, at the age of 43, between four miscarriages, she gave birth to a son, Robert Wiedeman Barrett Browning, whom they called Pen. Their son later married, but had no legitimate children.

At her husband's insistence, Elizabeth's second edition of ''Poems'' included her love sonnets; as a result, her popularity increased (as did critical regard), and her artistic position was confirmed.

The couple came to know a wide circle of artists and writers including William Makepeace Thackeray, sculptor

After the death of an old friend, G. B. Hunter, and then of her father, Barrett Browning's health started to deteriorate. The Brownings moved from

After the death of an old friend, G. B. Hunter, and then of her father, Barrett Browning's health started to deteriorate. The Brownings moved from

Barrett Browning's first known poem was written at the age of six or eight, "On the Cruelty of Forcement to Man". The manuscript, which protests against

Barrett Browning's first known poem was written at the age of six or eight, "On the Cruelty of Forcement to Man". The manuscript, which protests against

''The Brownings' Correspondence''

ed. Phillip Kelley, Ronald Hudson, and Scott Lewis. Winfield, Kansas: Wedgestone Press

Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning

at

Selected poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

;Physical collections *

Browning Family Collection

at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin

Digitized Browning love letters

at Baylor University

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

at the British Library * Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. ;Other resources *

Profile of Elizabeth Barrett Browning at PoetryFoundation.orgElizabeth Barrett Browning profile and poems at Poets.orgThe Brownings: A Research Guide (Baylor University)

www.florin.ms, website on Florence's 'English' Cemetery, with Elizabeth Barrett Browning's tomb by Frederick, Lord Leighton.

Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

at English Poetry {{DEFAULTSORT:Browning, Elizabeth Barrett 1806 births 1861 deaths 19th-century Congregationalists 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis 19th-century English poets 19th-century English women writers 19th-century translators Congregationalist abolitionists English abolitionists English Congregationalists English expatriates in Italy English women poets Epic poets Greek–English translators Infectious disease deaths in Tuscany People from Coxhoe People from Kelloe Sonneteers Tuberculosis deaths in Italy Victorian poets Victorian women writers

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

, popular in Britain and the United States during her lifetime.

Born in County Durham

County Durham ( ), officially simply Durham,UK General Acts 1997 c. 23Lieutenancies Act 1997 Schedule 1(3). From legislation.gov.uk, retrieved 6 April 2022. is a ceremonial county in North East England.North East Assembly �About North East E ...

, the eldest of 12 children, Elizabeth Barrett wrote poetry from the age of eleven. Her mother's collection of her poems forms one of the largest extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

collections of juvenilia

Juvenilia are literary, musical or artistic works produced by authors during their youth. Written juvenilia, if published at all, usually appears as a retrospective publication, some time after the author has become well known for later works.

...

by any English writer. At 15, she became ill, suffering intense head and spinal pain for the rest of her life. Later in life, she also developed lung problems, possibly tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

. She took laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum Linnaeus'') in alcohol (ethanol).

Red ...

for the pain from an early age, which is likely to have contributed to her frail health.

In the 1840s, Elizabeth was introduced to literary society through her distant cousin and patron John Kenyon. Her first adult collection of poems was published in 1838, and she wrote prolifically between 1841 and 1844, producing poetry, translation, and prose. She campaigned for the abolition of slavery, and her work helped influence reform in the child labour legislation. Her prolific output made her a rival to Tennyson as a candidate for poet laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) ...

on the death of Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

.

Elizabeth's volume ''Poems'' (1844) brought her great success, attracting the admiration of the writer Robert Browning

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose dramatic monologues put him high among the Victorian poets. He was noted for irony, characterization, dark humour, social commentary, historical settings ...

. Their correspondence, courtship, and marriage were carried out in secret, for fear of her father's disapproval. Following the wedding, she was indeed disinherited by her father. In 1846, the couple moved to Italy, where she would live for the rest of her life. They had a son, known as "Pen" ( Robert Wiedeman Barrett Browning) (1849–1912). Pen devoted himself to painting until his eyesight began to fail later in life; he also built up a large collection of manuscripts and memorabilia of his parents; however, since he died intestate, it was sold by public auction to various bidders, and scattered upon his death. The Armstrong Browning Library

The Armstrong Browning Library is located on the campus of Baylor University in Waco, Texas, USA and is the home of the largest collections of English poets Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Additionally it is thought to house the ...

has tried to recover some of his collection, and now houses the world's largest collection of Browning memorabilia. Elizabeth died in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

in 1861. A collection of her last poems was published by her husband shortly after her death.

Elizabeth's work had a major influence on prominent writers of the day, including the American poets Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

and Emily Dickinson. She is remembered for such poems as "How Do I Love Thee?

''How Do I Love Thee?'' is a 1970 American comedy-drama film directed by Michael Gordon. It stars Jackie Gleason and Maureen O'Hara and is based on Peter De Vries's 1965 novel ''Let Me Count the Ways''.

Plot

Tom Waltz, a college professor, ...

" (Sonnet 43, 1845) and '' Aurora Leigh ''(1856).

Life and career

Family background

Some of Elizabeth Barrett's family had lived inJamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

since 1655. Their wealth derived mainly from exploiting and extracting labour from slaves on their plantations in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

. Edward Barrett (1734–1798) was owner of in the estates of Cinnamon Hill, Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, and Oxford in northern Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

. Elizabeth's maternal grandfather owned sugar plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

farmed by slaves they bought from Africa, mills, glassworks, and ships that traded between Jamaica and Newcastle in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

.Marjorie Stone, "Browning, Elizabeth Barrett (1806–1861)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, October 2008.

The family wished to hand down their name, stipulating that Barrett should always be held as a surname. In some cases inheritance was given on condition that the name was used by the beneficiary; the English gentry and "squirearchy" had long encouraged this sort of name changing. Given this strong tradition, Elizabeth used "Elizabeth Barrett Moulton Barrett" on legal documents, and before she was married often signed herself "Elizabeth Barrett Barrett" or "EBB" (initials which she was able to keep after her wedding). Elizabeth's father chose to raise his family in England, while his business enterprises remained in Jamaica. Elizabeth's mother, Mary Graham Clarke, also owned several plantations also farmed by slaves in the British West Indies. The families built their wealth off buying and selling African people as slaves and using their free labour to build their massive fortunes.

Early life

Elizabeth Barrett Moulton-Barrett was born on (it is supposed) 6 March 1806, in Coxhoe Hall, between the villages of Coxhoe andKelloe

Kelloe is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in County Durham, England. The population of the civil parish as taken at the 2011 Census was 1,502. It is situated to the south-east of Durham, England, Durham.

History

The villag ...

in County Durham, England. Her parents were Edward Barrett Moulton-Barrett and Mary Graham Clarke. However, it has been suggested that, when she was christened on 9 March, she was already three or four months old, and that this was concealed because her parents had married only on 14 May 1805. Although she had already been baptised by a family friend in that first week of her life, she was baptised again, more publicly, on 10 February 1808 at Kelloe parish church, at the same time as her younger brother, Edward (known as "Bro"). He had been born in June 1807, only fifteen months after Elizabeth's stated date of birth. A private christening might seem unlikely for a family of standing and, while Bro's birth was celebrated with a holiday on the family's Caribbean plantations, Elizabeth's was not.

Elizabeth was the eldest of 12 children (eight boys and four girls). Eleven lived to adulthood; one daughter died at the age of three, when Elizabeth was eight. The children all had nicknames: Elizabeth was "Ba". She rode her pony, went for family walks and picnics, socialised with other county families, and participated in home theatrical productions. But unlike her siblings, she immersed herself in books as often as she could get away from the social rituals of her family.

In 1809, the family moved to Hope End, a estate near the Malvern Hills in Ledbury

Ledbury is a market town and civil parish in the county of Herefordshire, England, lying east of Hereford, and west of the Malvern Hills.

It has a significant number of timber-framed structures, in particular along Church Lane and High Street ...

, Herefordshire. Her father converted the Georgian house into stables and built a new mansion of opulent Turkish design, which his wife described as something from the ''Arabian Nights Entertainments''.

The interior's brass balustrades, mahogany doors inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and finely carved fireplaces were eventually complemented by lavish landscaping: ponds, grottos, kiosks, an ice house, a hothouse, and a subterranean passage from house to gardens.Taylor, Beverly. "Elizabeth Barrett Browning." Victorian Women Poets. Ed. William B. Thesing. Detroit: Gale Research, 1999. ''Dictionary of Literary Biography'' Vol. 199. Literature Resource Center. Web. 5 December 2014. Her time at Hope End would inspire her in later life to write her most ambitious work, '' Aurora Leigh'' (1856), which went through more than 20 editions by 1900, but none between 1905 and 1978.

She was educated at home and tutored by Daniel McSwiney with her oldest brother. She began writing verses at the age of four."Browning, Elizabeth Barrett: Introduction." Jessica Bomarito and Jeffrey W. Hunter (eds). ''Feminism in Literature: A Gale Critical Companion''. Vol. 2: 19th Century, Topics & Authors (A-B). Detroit: Gale, 2005. 467–469. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 December 2014. During the Hope End period, she was an intensely studious, precocious child.Taplin, Gardner B. ''The Life of Elizabeth Browning'' New Haven: Yale University Press (1957). She claimed that at the age of six, she was reading novels, at eight entranced by

She was educated at home and tutored by Daniel McSwiney with her oldest brother. She began writing verses at the age of four."Browning, Elizabeth Barrett: Introduction." Jessica Bomarito and Jeffrey W. Hunter (eds). ''Feminism in Literature: A Gale Critical Companion''. Vol. 2: 19th Century, Topics & Authors (A-B). Detroit: Gale, 2005. 467–469. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 December 2014. During the Hope End period, she was an intensely studious, precocious child.Taplin, Gardner B. ''The Life of Elizabeth Browning'' New Haven: Yale University Press (1957). She claimed that at the age of six, she was reading novels, at eight entranced by Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

's translations of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, studying Greek at ten, and at eleven, writing her own Homeric epic

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, '' The Battle of Marathon: A Poem''.

In 1820, Mr Barrett privately published ''The Battle of Marathon'', an epic-style poem, though all copies remained within the family. Her mother compiled the child's poetry into collections of "Poems by Elizabeth B. Barrett". Her father called her the "Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) ...

of Hope End" and encouraged her work. The result is one of the largest collections of juvenilia of any English writer. Mary Russell Mitford described the young Elizabeth at this time, as having "a slight, delicate figure, with a shower of dark curls falling on each side of a most expressive face; large, tender eyes, richly fringed by dark eyelashes, and a smile like a sunbeam."

At about this time, Elizabeth began to battle with illness, which the medical science of the time was unable to diagnose. All three sisters came down with the syndrome although it lasted only with Elizabeth. She had intense head and spinal pain with loss of mobility. Various biographies link this to a riding accident at the time (she fell while trying to dismount a horse), but there is no evidence to support the link. Sent to recover at the Gloucester spa, she was treated – in the absence of symptoms supporting another diagnosis – for a spinal problem. Though this illness continued for the rest of her life, it is believed to be unrelated to the lung disease which she developed in 1837.

She began to take opiates for the pain, laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum Linnaeus'') in alcohol (ethanol).

Red ...

(an opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

concoction) followed by morphine, then commonly prescribed. She would become dependent on them for much of her adulthood; the use from an early age may well have contributed to her frail health. Biographers such as Alethea Hayter have suggested this may also have contributed to the wild vividness of her imagination and the poetry that it produced.

By 1821, she had read Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

's '' A Vindication of the Rights of Woman'' (1792), and become a passionate supporter of Wollstonecraft's ideas. The child's intellectual fascination with the classics and metaphysics was reflected in a religious intensity which she later described as "not the deep persuasion of the mild Christian but the wild visions of an enthusiast." The Barretts attended services at the nearest Dissenting chapel, and Edward was active in Bible and missionary societies

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

.

tuberculous

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

ulceration of the lungs. That same year, at her physician's insistence, she moved from London to Torquay

Torquay ( ) is a seaside town in Devon, England, part of the unitary authority area of Torbay. It lies south of the county town of Exeter and east-north-east of Plymouth, on the north of Tor Bay, adjoining the neighbouring town of Paignton ...

, on the Devonshire coast. Her former home now forms part of the Regina Hotel. Two tragedies then struck. In February 1840, her brother Samuel died of a fever in Jamaica. Then her favourite brother Edward ("Bro") was drowned in a sailing accident in Torquay in July. This had a serious effect on her already fragile health. She felt guilty as her father had disapproved of Edward's trip to Torquay. She wrote to Mitford, "That was a very near escape from madness, absolute hopeless madness". The family returned to Wimpole Street in 1841.

Success

At Wimpole Street, Elizabeth spent most of her time in her upstairs room. Her health began to improve, though she saw few people other than her immediate family. One of those was John Kenyon, a wealthy friend and distant cousin of the family and patron of the arts. She received comfort from a spaniel named Flush, a gift from Mary Mitford. (

At Wimpole Street, Elizabeth spent most of her time in her upstairs room. Her health began to improve, though she saw few people other than her immediate family. One of those was John Kenyon, a wealthy friend and distant cousin of the family and patron of the arts. She received comfort from a spaniel named Flush, a gift from Mary Mitford. (Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

later fictionalised the life of the dog, making him the protagonist of her 1933 novel '' Flush: A Biography'').

Between 1841 and 1844, Elizabeth was prolific in poetry, translation, and prose. The poem ''The Cry of the Children

''The Cry of the Children'' is a 1912 American silent short drama film directed by George Nichols for the Thanhouser Company. The production, based on the poem by Elizabeth Barrett Browning about child labor, stars Marie Eline, Ethel Wright, a ...

'', published in 1842 in '' Blackwood's'', condemned child labour and helped bring about child-labour reforms by raising support for Lord Shaftesbury

Earl of Shaftesbury is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1672 for Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley, a prominent politician in the Cabal then dominating the policies of King Charles II. He had already succeeded his fa ...

's Ten Hours Bill

The Factories Act 1847, also known as the Ten Hours Act was a United Kingdom Act of Parliament which restricted the working hours of women and young persons (13-18) in textile mills to 10 hours per day. The practicalities of running a textile mi ...

(1844). At about the same time, she contributed critical prose pieces to Richard Henry Horne's ''A New Spirit of the Age'', including a laudatory essay on Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

.

In 1844, she published the two-volume ''Poems'', which included "A Drama of Exile", "A Vision of Poets", and "Lady Geraldine's Courtship", and two substantial critical essays for 1842 issues of '' The Athenaeum''. A self-proclaimed "adorer of Carlyle", she sent a copy to him as "a tribute of admiration & respect", which began a correspondence between them. "Since she was not burdened with any domestic duties expected of her sisters, Barrett Browning could now devote herself entirely to the life of the mind, cultivating an enormous correspondence, reading widely". Her prolific output made her a rival to Tennyson as a candidate for poet laureate in 1850 on the death of Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

.

A Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), also known as the Royal Society of Arts, is a London-based organisation committed to finding practical solutions to social challenges. The RSA acronym is used m ...

blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

now commemorates Elizabeth at 50 Wimpole Street.

Robert Browning and Italy

Her 1844 volume ''Poems'' made her one of the most popular writers in the country, and inspired

Her 1844 volume ''Poems'' made her one of the most popular writers in the country, and inspired Robert Browning

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose dramatic monologues put him high among the Victorian poets. He was noted for irony, characterization, dark humour, social commentary, historical settings ...

to write to her. He wrote, "I love your verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett," praising their "fresh strange music, the affluent language, the exquisite pathos and true new brave thought."

Kenyon arranged for Browning to meet Elizabeth on 20 May 1845, in her rooms, and so began one of the most famous courtships in literature. Elizabeth had already produced a large amount of work, but Browning had a great influence on her subsequent writing, as did she on his: two of Barrett's most famous pieces were written after she met Browning, ''Sonnets from the Portuguese

''Sonnets from the Portuguese'', written ca. 1845–1846 and published first in 1850, is a collection of 44 love sonnets written by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The collection was acclaimed and popular during the poet's lifetime and it remain ...

'' and ''Aurora Leigh''. Robert's '' Men and Women'' is also a product of that time.

Some critics state that her activity was, in some ways, in decay before she met Browning: "Until her relationship with Robert Browning

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose dramatic monologues put him high among the Victorian poets. He was noted for irony, characterization, dark humour, social commentary, historical settings ...

began in 1845, Barrett's willingness to engage in public discourse about social issues and about aesthetic issues in poetry, which had been so strong in her youth, gradually diminished, as did her physical health. As an intellectual presence and a physical being, she was becoming a shadow of herself."

The courtship and marriage between Robert Browning and Elizabeth were carried out secretly, as she knew her father would disapprove. After a private marriage at St Marylebone Parish Church, they honeymooned in Paris before moving, in September 1846, to Italy, which became their home almost continuously until her death. Elizabeth's loyal lady's maid, Elizabeth Wilson, witnessed the marriage and accompanied the couple to Italy.

Mr Barrett disinherited Elizabeth, as he did each of his children who married. Elizabeth had foreseen her father's anger but had not anticipated her brothers' rejection. As Elizabeth had some money of her own, the couple were reasonably comfortable in Italy. The Brownings were well respected, and even famous. Elizabeth grew stronger and in 1849, at the age of 43, between four miscarriages, she gave birth to a son, Robert Wiedeman Barrett Browning, whom they called Pen. Their son later married, but had no legitimate children.

At her husband's insistence, Elizabeth's second edition of ''Poems'' included her love sonnets; as a result, her popularity increased (as did critical regard), and her artistic position was confirmed.

The couple came to know a wide circle of artists and writers including William Makepeace Thackeray, sculptor

The courtship and marriage between Robert Browning and Elizabeth were carried out secretly, as she knew her father would disapprove. After a private marriage at St Marylebone Parish Church, they honeymooned in Paris before moving, in September 1846, to Italy, which became their home almost continuously until her death. Elizabeth's loyal lady's maid, Elizabeth Wilson, witnessed the marriage and accompanied the couple to Italy.

Mr Barrett disinherited Elizabeth, as he did each of his children who married. Elizabeth had foreseen her father's anger but had not anticipated her brothers' rejection. As Elizabeth had some money of her own, the couple were reasonably comfortable in Italy. The Brownings were well respected, and even famous. Elizabeth grew stronger and in 1849, at the age of 43, between four miscarriages, she gave birth to a son, Robert Wiedeman Barrett Browning, whom they called Pen. Their son later married, but had no legitimate children.

At her husband's insistence, Elizabeth's second edition of ''Poems'' included her love sonnets; as a result, her popularity increased (as did critical regard), and her artistic position was confirmed.

The couple came to know a wide circle of artists and writers including William Makepeace Thackeray, sculptor Harriet Hosmer

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (October 9, 1830 – February 21, 1908) was a neoclassical sculptor, considered the most distinguished female sculptor in America during the 19th century. She is known as the first female professional sculptor. Among other ...

(who, she wrote, seemed to be the "perfectly emancipated female") and Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the harsh ...

. In 1849, she met Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

; Carlyle, in 1851; in 1852, French novelist George Sand, whom she had long admired. Among her intimate friends in Florence was the writer Isa Blagden

Isa or Isabella Jane Blagden (30 June 1816 or 1817 – 20 January 1873) was an English-language novelist, speaker, and poet born in the East Indies or India, who spent much of her life among the English community in Florence. She was notably frie ...

, whom she encouraged to write novels. They met Alfred Tennyson in Paris, and John Forster, Samuel Rogers

Samuel Rogers (30 July 1763 – 18 December 1855) was an English poet, during his lifetime one of the most celebrated, although his fame has long since been eclipsed by his Romantic colleagues and friends Wordsworth, Coleridge and Byron. His ...

and the Carlyles in London, later befriending Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the working ...

and John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and politi ...

.

Decline and death

After the death of an old friend, G. B. Hunter, and then of her father, Barrett Browning's health started to deteriorate. The Brownings moved from

After the death of an old friend, G. B. Hunter, and then of her father, Barrett Browning's health started to deteriorate. The Brownings moved from Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

to Siena

Siena ( , ; lat, Sena Iulia) is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.

The city is historically linked to commercial and banking activities, having been a major banking center until the 13th and 14th centuri ...

, residing at the ''Villa Alberti''. Engrossed in Italian politics, she issued a small volume of political poems titled ''Poems before Congress'' (1860) "most of which were written to express her sympathy with the Italian cause after the outbreak of fighting in 1859". They caused a furore in England, and the conservative magazines '' Blackwood's'' and the '' Saturday Review'' labelled her a fanatic. She dedicated this book to her husband. Her last work was ''A Musical Instrument'', published posthumously.

Barrett Browning's sister Henrietta died in November 1860. The couple spent the winter of 1860–61 in Rome where Barrett Browning's health further deteriorated and they returned to Florence in early June 1861. She became gradually weaker, using morphine to ease her pain. She died on 29 June 1861 in her husband's arms. Browning said that she died "smilingly, happily, and with a face like a girl's.... Her last word was... 'Beautiful' ". She was buried in the Protestant English Cemetery of Florence

The English Cemetery in Florence, Italy (Italian, ''Cimitero degli inglesi'', ''Cimitero Porta a' Pinti'' and ''Cimitero Protestante'') is an Evangelical cemetery located at Piazzale Donatello. Although its origins date to its foundation in 1827 ...

. "On Monday July 1 the shops in the area around Casa Guidi were closed, while Elizabeth was mourned with unusual demonstrations." The nature of her illness is still unclear. Some modern scientists speculate her illness may have been hypokalemic periodic paralysis, a genetic disorder that causes weakness and many of the other symptoms she described.

Publications

Barrett Browning's first known poem was written at the age of six or eight, "On the Cruelty of Forcement to Man". The manuscript, which protests against

Barrett Browning's first known poem was written at the age of six or eight, "On the Cruelty of Forcement to Man". The manuscript, which protests against impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

, is currently in the Berg Collection

The Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, commonly known as the Main Branch, 42nd Street Library or the New York Public Library, is the flagship building in the New York Public Library system in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. ...

of the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

; the exact date is controversial because the "2" in the date 1812 is written over something else that is scratched out.

Her first independent publication was "Stanzas Excited by Reflections on the Present State of Greece" in '' The New Monthly Magazine'' of May 1821; followed two months later by "Thoughts Awakened by Contemplating a Piece of the Palm which Grows on the Summit of the Acropolis at Athens".

Her first collection of poems, ''An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems,'' was published in 1826 and reflected her passion for Byron and Greek politics. Its publication drew the attention of a blind scholar of the Greek language, Hugh Stuart Boyd, and of another Greek scholar, Uvedale Price, with whom she maintained sustained correspondence. Among other neighbours was Mrs James Martin from Colwall, with whom she also corresponded throughout her life. Later, at Boyd's suggestion, she translated Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek ...

' '' Prometheus Bound'' (published in 1833; retranslated in 1850). During their friendship Barrett studied Greek literature, including Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar is ...

and Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states ...

.

Elizabeth opposed slavery and published two poems highlighting the barbarity of the institution and her support for the abolitionist cause: "The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point" and "A Curse for a Nation". The first depicts an enslaved woman whipped, raped, and made pregnant cursing her enslavers. Elizabeth declared herself glad that the slaves were "virtually free" when the Slavery Abolition Act passed in the British Parliament, despite the fact that her father believed that abolition

Abolition refers to the act of putting an end to something by law, and may refer to:

* Abolitionism, abolition of slavery

* Abolition of the death penalty, also called capital punishment

* Abolition of monarchy

*Abolition of nuclear weapons

*Abol ...

would ruin his business.

The date of publication of these poems is in dispute, but her position on slavery in the poems is clear and may have led to a rift between Elizabeth and her father. She wrote to John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and politi ...

in 1855 "I belong to a family of West Indian slaveholders, and if I believed in curses, I should be afraid". Her father and uncle were unaffected by the Baptist War (1831–1832) and continued to own slaves until passage of the Slavery Abolition Act.

In London, John Kenyon introduced Elizabeth to literary figures including William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

, Mary Russell Mitford, Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poe ...

, Alfred Tennyson and Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

. Elizabeth continued to write, contributing "The Romaunt of Margaret", "The Romaunt of the Page", "The Poet's Vow" and other pieces to various periodicals. She corresponded with other writers, including Mary Russell Mitford, who would become a close friend and who would support Elizabeth's literary ambitions.

In 1838 ''The Seraphim and Other Poems'' appeared, the first volume of Elizabeth's mature poetry to appear under her own name.

''Sonnets from the Portuguese

''Sonnets from the Portuguese'', written ca. 1845–1846 and published first in 1850, is a collection of 44 love sonnets written by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The collection was acclaimed and popular during the poet's lifetime and it remain ...

'' was published in 1850. There is debate about the origin of the title. Some say it refers to the series of sonnets of the 16th-century Portuguese poet Luís de Camões. However, "my little Portuguese" was a pet name that Browning had adopted for Elizabeth and this may have some connection.

The verse-novel ''Aurora Leigh,'' her most ambitious and perhaps the most popular of her longer poems, appeared in 1856. It is the story of a female writer making her way in life, balancing work and love, and based on Elizabeth's own experiences. ''Aurora Leigh'' was an important influence on Susan B. Anthony's thinking about the traditional roles of women, with regard to marriage versus independent individuality. The '' North American Review'' praised Elizabeth's poem: "Mrs. Browning's poems are, in all respects, the utterance of a woman — of a woman of great learning, rich experience, and powerful genius, uniting to her woman's nature the strength which is sometimes thought peculiar to a man."

Spiritual influence

Much of Barrett Browning's work carries a religious theme. She had read and studied such works asMilton

Milton may refer to:

Names

* Milton (surname), a surname (and list of people with that surname)

** John Milton (1608–1674), English poet

* Milton (given name)

** Milton Friedman (1912–2006), Nobel laureate in Economics, author of '' Free t ...

's ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse (poetry), verse. A second edition fo ...

'' and Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

's ''Inferno

Inferno may refer to:

* Hell, an afterlife place of suffering

* Conflagration, a large uncontrolled fire

Film

* ''L'Inferno'', a 1911 Italian film

* Inferno (1953 film), ''Inferno'' (1953 film), a film noir by Roy Ward Baker

* Inferno (1973 fi ...

''. She says in her writing, "We want the sense of the saturation of Christ's blood upon the souls of our poets, that it may cry through them in answer to the ceaseless wail of the Sphinx of our humanity, expounding agony into renovation. Something of this has been perceived in art when its glory was at the fullest. Something of a yearning after this may be seen among the Greek Christian poets, something which would have been much with a stronger faculty". She believed that "Christ's religion is essentially poetry – poetry glorified". She explored the religious aspect in many of her poems, especially in her early work, such as the sonnets.

She was interested in theological debate, had learned Hebrew and read the Hebrew Bible. Her seminal ''Aurora Leigh'', for example, features religious imagery and allusion to the apocalypse. The critic Cynthia Scheinberg notes that female characters in ''Aurora Leigh'' and her earlier work "The Virgin Mary to the Child Jesus" allude to Miriam, sister and caregiver to Moses. These allusions to Miriam in both poems mirror the way in which Barrett Browning herself drew from Jewish history, while distancing herself from it, in order to maintain the cultural norms of a Christian woman poet of the Victorian Age.

In the correspondence Barrett Browning kept with the Reverend William Merry from 1843 to 1844 on predestination and salvation by works, she identifies herself as a Congregationalist: "I am not a Baptist — but a Congregational Christian, — in the holding of my private opinions."

Barrett Browning Institute

In 1892, Ledbury, Herefordshire, held a design competition to build an Institute in honour of Barrett Browning. Brightwen Binyon beat 44 other designs. It was based on the timber-framed Market House, which was opposite the site, and was completed in 1896. However,Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, ''The Buildings of England'' (1 ...

was not impressed by its style. It was used as a public library from 1938, until new library facilities were provided for the town, and is now the headquarters of the Ledbury Poetry Festival

Founded in 1996 by a group of local poetry enthusiasts, the Ledbury Poetry Festival is now the biggest poetry festival in the UK.

History

The first Ledbury Poetry Festival was held in 1997 in Ledbury, Herefordshire. It was opened by jazz singer ...

. It has been Grade II-listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

since 2007.

Critical reception

Barrett Browning was widely popular in the United Kingdom and the United States during her lifetime.Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

was inspired by her poem ''Lady Geraldine's Courtship'' and specifically borrowed the poem's metre for his poem '' The Raven''. Poe had reviewed Barrett Browning's work in the January 1845 issue of the '' Broadway Journal'', saying that "her poetic inspiration is the highest – we can conceive of nothing more august. Her sense of Art is pure in itself." In return, she praised '' The Raven'', and Poe dedicated his 1845 collection ''The Raven and Other Poems'' to her, referring to her as "the noblest of her sex".

Barrett Browning's poetry greatly influenced Emily Dickinson, who admired her as a woman of achievement. Her popularity in the United States and Britain was further advanced by her stands against social injustice, including slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Sl ...

, injustice toward Italians from their foreign rulers, and child labour.

Lilian Whiting

Lilian Whiting (October 3, 1847 – April 30, 1942) was an American journalist, editor, and author of poetry and short stories. Her father was Illinois State Senator Lorenzo D. Whiting. She served as literary editor of the ''Boston Evening Tr ...

published a biography of Barrett Browning (1899) which describes her as "the most philosophical poet" and depicts her life as "a Gospel of applied Christianity". To Whiting, the term "art for art's sake" did not apply to Barrett Browning's work, as each poem, distinctively purposeful, was borne of a more "honest vision". In this critical analysis, Whiting portrays Barrett Browning as a poet who uses knowledge of Classical literature with an "intuitive gift of spiritual divination".Whiting, Lilian. ''A study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning''. Little, Brown and Company (1899) In ''Elizabeth Barrett Browning'', Angela Leighton suggests that the portrayal of Barrett Browning as the "pious iconography of womanhood" has distracted us from her poetic achievements. Leighton cites the 1931 play by Rudolf Besier

Rudolf Wilhelm Besier (2 July 1878 – 16 June 1942) was a Dutch/English dramatist and translator best known for his play ''The Barretts of Wimpole Street'' (1930). He worked with H. G. Wells, Hugh Walpole and May Edginton on dramatisations.

Ear ...

''The Barretts of Wimpole Street

''The Barretts of Wimpole Street'' is a 1930 play by the Dutch/English dramatist Rudolf Besier, based on the romance between Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett, and her father's unwillingness to allow them to marry. The play gave actress Ka ...

'' as evidence that 20th-century literary criticism of Barrett Browning's work has suffered more as a result of her popularity than poetic ineptitude. The play was popularized by actress Katharine Cornell

Katharine Cornell (February 16, 1893June 9, 1974) was an American stage actress, writer, theater owner and producer. She was born in Berlin to American parents and raised in Buffalo, New York.

Dubbed "The First Lady of the Theatre" by critic A ...

, for whom it became a signature role. It was an enormous success, both artistically and commercially, and was revived several times and adapted twice into movies. Sampson, however, considers the play to have been the most damaging cause of false myths about Elizabeth, and particularly the relationship with her, allegedly 'tyrannical', father. Sampson, Fiona (2021). ''Two Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning''. Profile Books, pp 4-5

Throughout the 20th century, literary criticism of Barrett Browning's poetry remained sparse until her poems were discovered by the women's movement. She once described herself as being inclined to reject several women's rights principles, suggesting in letters to Mary Russell Mitford and her husband that she believed that there was an inferiority of intellect in women. In ''Aurora Leigh'', however, she created a strong and independent woman who embraces both work and love. Leighton writes that because Elizabeth participates in the literary world, where voice and diction are dominated by perceived masculine superiority, she "is defined only in mysterious opposition to everything that distinguishes the male subject who writes..." A five-volume scholarly edition of her works was published in 2010, the first in over a century.

Works (collections)

*1820: '' The Battle of Marathon: A Poem''. Privately printed *1826: ''An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems''. London: James Duncan *1833: ''Prometheus Bound, Translated from the Greek of Aeschylus, and Miscellaneous Poems''. London: A.J. Valpy *1838: ''The Seraphim, and Other Poems''. London: Saunders and Otley *1844: ''Poems'' (UK) / ''A Drama of Exile, and other Poems'' (US). London: Edward Moxon. New York: Henry G. Langley *1850: ''Poems'' ("New Edition", 2 vols.) Revision of 1844 edition adding ''Sonnets from the Portuguese'' and others. London: Chapman & Hall *1851: ''Casa Guidi Windows''. London: Chapman & Hall *1853: ''Poems'' (3d ed.). London: Chapman & Hall *1854: ''Two Poems'': "A Plea for the Ragged Schools of London" (by Elizabeth Barrett Browning) and "The Twins" (by Robert Browning). London: Chapman & Hall *1856: ''Poems'' (4th ed.). London: Chapman & Hall *1856: ''Aurora Leigh''. London: Chapman & Hall *1860: ''Poems Before Congress''. London: Chapman & Hall *1862: ''Last Poems''. London: Chapman & HallPosthumous publications

*1863: ''The Greek Christian Poets and the English Poets''. London: Chapman & Hall *1877: ''The Earlier Poems of Elizabeth Barrett Browning,'' 1826–1833, ed. Richard Herne Shepherd. London: Bartholomew Robson *1877: ''Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning Addressed to Richard Hengist Horne, with comments on contemporaries,'' 2 vols., ed. S.R.T. Mayer. London: Richard Bentley & Son *1897: ''Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning,'' 2 vols., ed. Frederic G. Kenyon. London:Smith, Elder,& Co. *1899: ''Letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Barrett 1845–1846,'' 2 vol., ed Robert W. Barrett Browning. London: Smith, Elder & Co. *1914: ''New Poems by Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning,'' ed. Frederic G Kenyon. London: Smith, Elder & Co. *1929: ''Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Letters to Her Sister, 1846–1859,'' ed. Leonard Huxley. London: John Murray *1935: ''Twenty-Two Unpublished Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning to Henrietta and Arabella Moulton Barrett''. New York: United Feature Syndicate *1939: ''Letters from Elizabeth Barrett to B.R. Haydon,'' ed. Martha Hale Shackford. New York: Oxford University Press *1954: ''Elizabeth Barrett to Miss Mitford,'' ed. Betty Miller. London: John Murray *1955: ''Unpublished Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Hugh Stuart Boyd,'' ed. Barbara P. McCarthy. New Heaven, Conn.: Yale University Press *1958: ''Letters of the Brownings to George Barrett,'' ed. Paul Landis with Ronald E. Freeman. Urbana: University of Illinois Press *1974: ''Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Letters to Mrs. David Ogilvy,'' 1849–1861, ed. P. Heydon and P. Kelley. New York: Quadrangle, New York Times Book Co., and Browning Institute *1984''The Brownings' Correspondence''

ed. Phillip Kelley, Ronald Hudson, and Scott Lewis. Winfield, Kansas: Wedgestone Press

Notes

References

Further reading

*Barrett, Robert Assheton. ''The Barretts of Jamaica – The family of Elizabeth Barrett Browning'' (1927). Armstrong Browning Library of Baylor University, Browning Society, Wedgestone Press in Winfield, Kan, 2000. *Elizabeth Barrett Browning. "Aurora Leigh and Other Poems", eds. John Robert Glorney Bolton and Julia Bolton Holloway. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1995. *Donaldson, Sandra, et al., eds. ''The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.'' 5 vols. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2010. *''The Complete Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning'', eds. Charlotte Porter and Helen A. Clarke. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1900. *Creston, Dormer. ''Andromeda in Wimpole Street: The Romance of Elizabeth Barrett Browning''. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1929. *Everett, Glenn. ''Life of Elizabeth Browning''. The Victorian Web 2002. * Forster, Margaret. ''Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (née Moulton-Barrett; 6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was an English poet of the Victorian era, popular in Britain and the United States during her lifetime.

Born in County Durham, the eldest of 12 children, Elizabet ...

''. New York: Random House, Vintage Classics, 2004.

*Hayter, Alethea. ''Elizabeth Barrett Browning'' (published for the British Council and the National Book League). London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1965.

*Kaplan, Cora. ''Aurora Leigh and Other Poems''. London: The Women's Press Limited, 1978.

*Kelley, Philip et al. (Eds.) ''The Brownings' Correspondence''. 27 vols. to date. (Wedgestone, 1984–) (Complete letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning, so far to 1860.)

*Lewis, Linda. ''Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Spiritual Progress''. Missouri: Missouri University Press. 1997.

*Mander, Rosalie. ''Mrs Browning: The Story of Elizabeth Barrett''. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980.

*Marks, Jeannette. ''The Family of the Barrett: A Colonial Romance''. London: Macmillan, 1938.

*Markus, Julia. ''Dared and Done: Marriage of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning''. Ohio University Press, 1995.

*Meyers, Jeffrey. ''Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy''. New York City: Cooper Square Press, 1992: 160.

*Peterson, William S. ''Sonnets from the Portuguese''. Massachusetts: Barre Publishing, 1977.

*Pollock, Mary Sanders. ''Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning: A Creative Partnership''. England: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2003.

* Sampson, Fiona. ''Two Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning''. Profile Books, 2021.

*Sova, Dawn B. ''Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z.'' New York City: Checkmark Books, 2001.

*Stephenson Glennis. ''Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the Poetry of Love''. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1989.

*Taplin, Gardner B. ''The Life of Elizabeth Browning''. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957.

*Thomas, Dwight and David K. Jackson. ''The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, 1809–1849''. New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1987: 591.

External links

;Digital collections * * * *Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning

at

Online Books Page

The Online Books Page is an index of e-text books available on the Internet. It is edited by John Mark Ockerbloom and is hosted by the library of the University of Pennsylvania. The Online Books Page lists over 2 million books and has several feat ...

Selected poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

;Physical collections *

Browning Family Collection

at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin

Digitized Browning love letters

at Baylor University

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

at the British Library * Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. ;Other resources *

Profile of Elizabeth Barrett Browning at PoetryFoundation.org

www.florin.ms, website on Florence's 'English' Cemetery, with Elizabeth Barrett Browning's tomb by Frederick, Lord Leighton.

Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

at English Poetry {{DEFAULTSORT:Browning, Elizabeth Barrett 1806 births 1861 deaths 19th-century Congregationalists 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis 19th-century English poets 19th-century English women writers 19th-century translators Congregationalist abolitionists English abolitionists English Congregationalists English expatriates in Italy English women poets Epic poets Greek–English translators Infectious disease deaths in Tuscany People from Coxhoe People from Kelloe Sonneteers Tuberculosis deaths in Italy Victorian poets Victorian women writers