Edward Osborne Wilson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

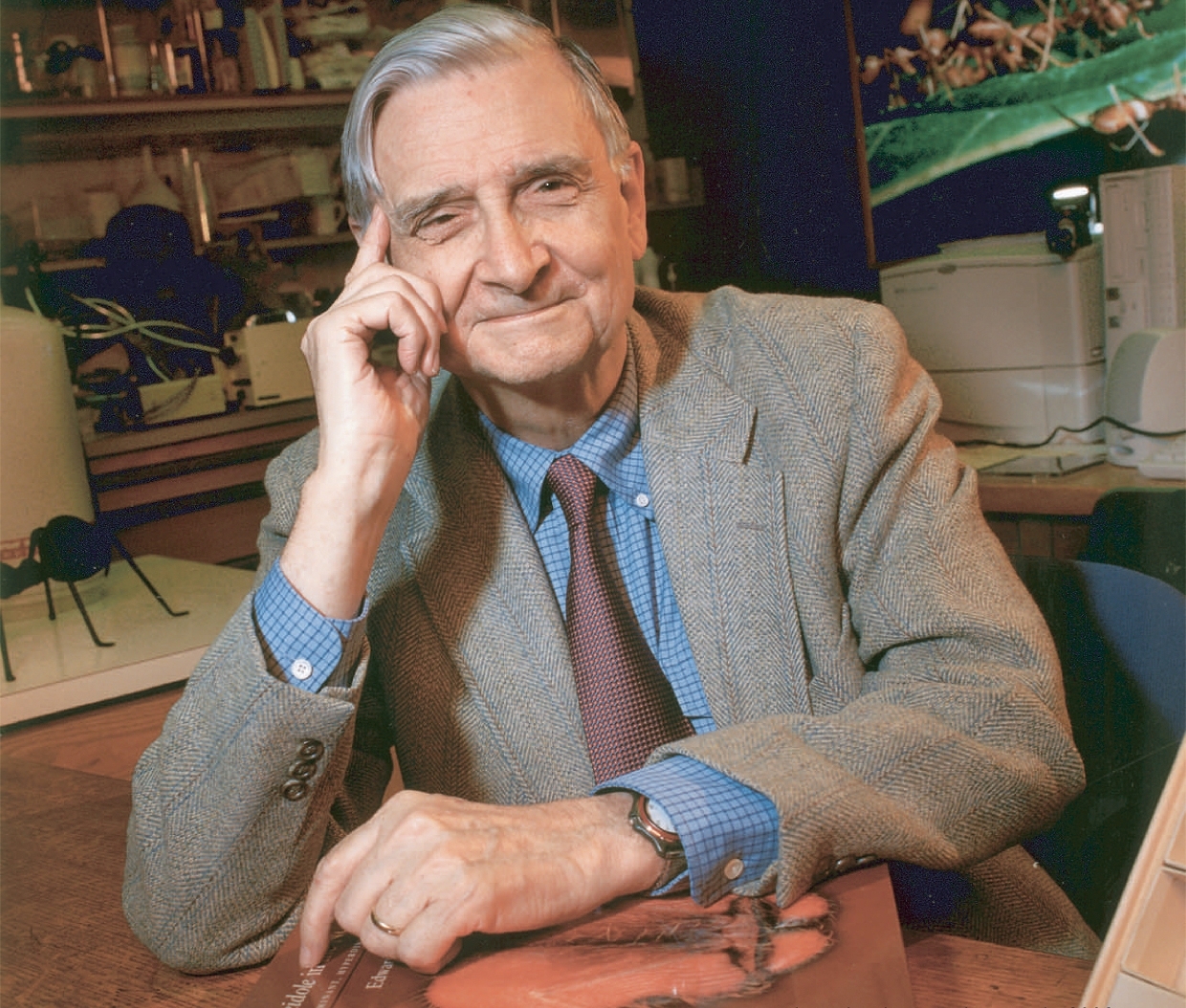

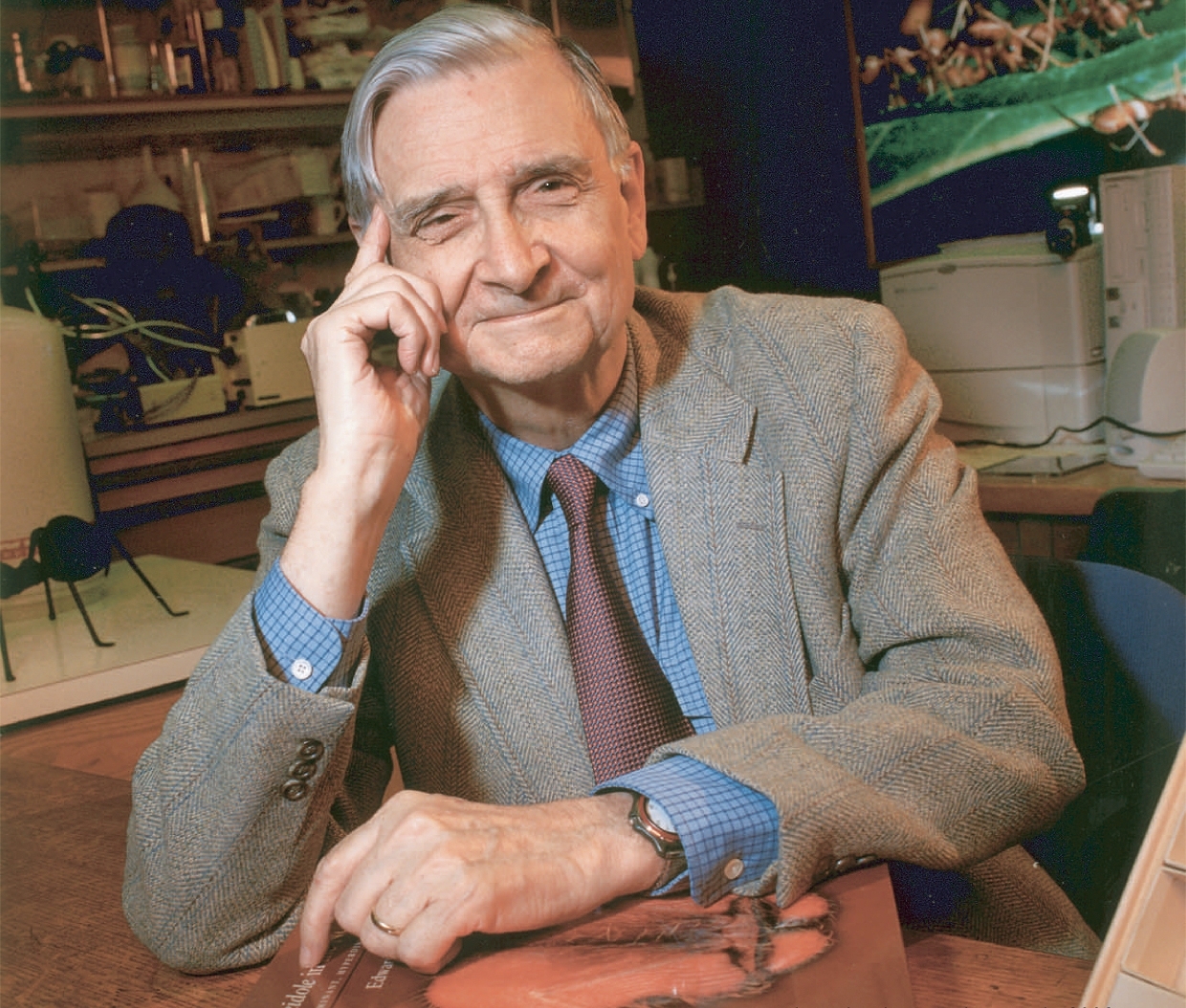

Edward Osborne Wilson (June 10, 1929 – December 26, 2021) was an American

From 1956 until 1996, Wilson was part of the faculty of Harvard. He began as an ant

From 1956 until 1996, Wilson was part of the faculty of Harvard. He began as an ant

biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

, naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

, ecologist

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere levels. Ecology overlaps with the closely re ...

, and entomologist

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

known for developing the field of sociobiology

Sociobiology is a field of biology that aims to explain social behavior in terms of evolution. It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics. Within the study of ...

.

Born in Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, Wilson found an early interest in nature and frequented the outdoors. At age seven, he was partially blinded in a fishing accident; due to his reduced sight, Wilson resolved to study entomology

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

. After graduating from the University of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, the Capstone, or Bama) is a Public university, public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, United States. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of ...

, Wilson transferred to complete his dissertation at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, where he distinguished himself in multiple fields. In 1956, he co-authored a paper defining the theory of character displacement

Character or Characters may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''Character'' (novel), a 1936 Dutch novel by Ferdinand Bordewijk

* ''Characters'' (Theophrastus), a classical Greek set of character sketches attributed to Theoph ...

. In 1967, he developed the theory of island biogeography

Insular biogeography or island biogeography is a field within biogeography that examines the factors that affect the species richness and diversification of isolated natural communities. The theory was originally developed to explain the pattern ...

with Robert MacArthur

Robert Helmer MacArthur (April 7, 1930 – November 1, 1972) was a Canadian-born American ecologist who made a major impact on many areas of community and population ecology. He is considered to be one of the founders of ecology.

Early life ...

.

Wilson was the Pellegrino University Research Professor Emeritus in Entomology for the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, a lecturer at Duke University

Duke University is a Private university, private research university in Durham, North Carolina, United States. Founded by Methodists and Quakers in the present-day city of Trinity, North Carolina, Trinity in 1838, the school moved to Durham in 1 ...

, and a fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry

The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI), formerly known as the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), is a program within the U.S. non-profit organization Center for Inquiry (CFI), which seeks to " ...

. The Royal Swedish Academy awarded Wilson the Crafoord Prize

The Crafoord Prize () is an annual science prize established in 1980 by Holger Crafoord, a Swedish industrialist, and his wife Anna-Greta Crafoord following a donation to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. It is awarded jointly by the Acade ...

. He was a humanist laureate of the International Academy of Humanism

The International Academy of Humanism, established in 1983, is a programme of the Council for Secular Humanism. It was established to recognize great humanists and disseminate humanist thinking. According to its declared mission, members of the ...

. He was a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction

The Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are awarded annually for the "Letters, Drama, and Music" category. The award is given to a nonfiction book written by an American author and published du ...

(for '' On Human Nature'' in 1979

Events

January

* January 1

** United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim heralds the start of the ''International Year of the Child''. Many musicians donate to the ''Music for UNICEF Concert'' fund, among them ABBA, who write the song ...

, and ''The Ants

''The Ants'' is a zoology textbook by the German entomologist Bert Hölldobler and the American entomologist E. O. Wilson, first published in 1990. It won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 1991.

Contents

This book is primarily aimed a ...

'' in 1991

It was the final year of the Cold War, which had begun in 1947. During the year, the Soviet Union Dissolution of the Soviet Union, collapsed, leaving Post-soviet states, fifteen sovereign republics and the Commonwealth of Independent State ...

) and a ''New York Times'' bestselling author for '' The Social Conquest of Earth'', '' Letters to a Young Scientist'', and ''The Meaning of Human Existence''.

Wilson's work received both praise and criticism during his lifetime. His 1975 book '' Sociobiology: The New Synthesis'' was a particular flashpoint for controversy, and drew criticism from the Sociobiology Study Group The Sociobiology Study Group was an academic organization formed to specifically counter sociobiological explanations of human behavior, particularly those expounded by the Harvard entomologist E. O. Wilson in '' Sociobiology: The New Synthesis'' ( ...

. Wilson's interpretation of the theory of evolution resulted in a widely reported dispute with Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, zoologist, science communicator and author. He is an Oxford fellow, emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford, and was Simonyi Professor for the Publ ...

about multilevel selection theory

Group selection is a proposed mechanism of evolution in which natural selection acts at the level of the group, instead of at the level of the individual or gene.

Early authors such as V. C. Wynne-Edwards and Konrad Lorenz argued that the behav ...

. Examinations of his letters after his death revealed that he had supported the psychologist J. Philippe Rushton, whose work on race and intelligence

Discussions of race and intelligence—specifically regarding claims of differences in intelligence along racial lines—have appeared in both popular science and academic research since the modern concept of race was first introduced. With th ...

is widely regarded by the scientific community as deeply flawed and racist.

Early life

Edward Osborne Wilson was born on June 10, 1929, inBirmingham, Alabama

Birmingham ( ) is a city in the north central region of Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Jefferson County, Alabama, Jefferson County. The population was 200,733 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List ...

. He was the only child of Inez Linnette Freeman and Edward Osborne Wilson Sr. According to his autobiography, ''Naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

'', he grew up in various towns in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

which included Mobile, Decatur, and Pensacola

Pensacola ( ) is a city in the Florida panhandle in the United States. It is the county seat and only city in Escambia County. The population was 54,312 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Pensacola metropolitan area, which ha ...

. From an early age, he was interested in natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. His father was an alcoholic who eventually committed suicide. His parents allowed him to bring home black widow spiders and keep them on the porch. They divorced when he was seven years old.

In the same year that his parents divorced, Wilson blinded himself in his right eye in a fishing accident. Despite the prolonged pain, he did not stop fishing. He did not complain because he was anxious to stay outdoors, and never sought medical treatment. Several months later, his right pupil clouded over with a cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens (anatomy), lens of the eye that leads to a visual impairment, decrease in vision of the eye. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colours, blurry or ...

. He was admitted to Pensacola Hospital to have the lens removed. Wilson writes, in his autobiography, that the "surgery was a terrifying 9thcentury ordeal". Wilson retained full sight in his left eye, with a vision of 20/10. The 20/10 vision prompted him to focus on "little things": "I noticed butterflies and ants more than other kids did, and took an interest in them automatically." Although he had lost his stereoscopic vision

Binocular vision is seeing with two eyes, which increases the size of the visual field. If the visual fields of the two eyes overlap, binocular depth can be seen. This allows objects to be recognized more quickly, camouflage to be detected, spa ...

, he could still see fine print and the hairs on the bodies of small insects. His reduced ability to observe mammals and birds led him to concentrate on insects.

At the age of nine, Wilson undertook his first expeditions at Rock Creek Park

Rock Creek Park is a large urban park that bisects the Northwest, Washington, D.C., Northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C. Created by Act of Congress in 1890, the park comprises 1,754 acres (2.74 mi2, 7.10 km2), generally along Rock Cr ...

in Washington, D.C. He began to collect insects and he gained a passion for butterflies. He would capture them using nets made with brooms, coat hangers, and cheesecloth bags. Going on these expeditions led to Wilson's fascination with ants. He describes in his autobiography how one day he pulled the bark of a rotting tree away and discovered citronella ants underneath. The worker ants he found were "short, fat, brilliant yellow, and emitted a strong lemony odor". Wilson said the event left a "vivid and lasting impression". He also earned the Eagle Scout

Eagle Scout is the highest rank attainable in the Scouts BSA program of Scouting America. Since its inception in 1911, only four percent of Scouts have earned this rank after a lengthy review process. The Eagle Scout rank has been earned by over ...

award and served as Nature Director of his Boy Scouts

Boy Scouts or Boy Scout may refer to:

* Members, sections or organisations in the Scouting Movement

** Scout (Scouting), a boy or a girl participating in the worldwide Scouting movement

** Scouting America, formerly known as Boy Scouts of America ...

summer camp. At age 18, intent on becoming an entomologist

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

, he began by collecting flies

Flies are insects of the Order (biology), order Diptera, the name being derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwin ...

, but the shortage of insect pins during World War II caused him to switch to ant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

s, which could be stored in vials. With the encouragement of Marion R. Smith, a myrmecologist from the National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. With 4.4 ...

in Washington, Wilson began a survey of all the ants of Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

. This study led him to report the first colony of fire ants

Fire ants are several species of ants in the genus ''Solenopsis'', which includes over 200 species. ''Solenopsis'' are stinging ants, and most of their common names reflect this, for example, ginger ants and tropical fire ants. Many of the nam ...

in the U.S., near the port of Mobile.

Education

Wilson said he went to 15 or 16 schools during 11 years of schooling. He was concerned that he might not be able to afford to go to a university, and he tried to enlist in the United States Army, intending to earn U.S. government financial support for his education. He failed the Army medical examination due to his impaired eyesight, but was able to afford to enroll in theUniversity of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, the Capstone, or Bama) is a Public university, public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, United States. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of ...

, where he earned his Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, B.S., B.Sc., SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree that is awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Scienc ...

in 1949 and Master of Science

A Master of Science (; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree. In contrast to the Master of Arts degree, the Master of Science degree is typically granted for studies in sciences, engineering and medici ...

in biology in 1950. The next year, Wilson transferred to Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

.

Appointed to the Harvard Society of Fellows The Society of Fellows is a group of scholars selected at the beginnings of their careers by Harvard University for their potential to advance academic wisdom, upon whom are bestowed distinctive opportunities to foster their individual and intellect ...

, he traveled on overseas expeditions, collecting ant species from Cuba and Mexico and traveling the South Pacific, including Australia, New Guinea, Fiji, and New Caledonia, as well as to Sri Lanka. In 1955, he received his Ph.D. and married Irene Kelley.

In '' Letters to a Young Scientist'', Wilson stated his IQ was measured as 123.

Career

From 1956 until 1996, Wilson was part of the faculty of Harvard. He began as an ant

From 1956 until 1996, Wilson was part of the faculty of Harvard. He began as an ant taxonomist

In biology, taxonomy () is the science, scientific study of naming, defining (Circumscription (taxonomy), circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxon, taxa (si ...

and worked on understanding their microevolution

Microevolution is the change in allele frequencies that occurs over time within a population. This change is due to four different processes: mutation, selection ( natural and artificial), gene flow and genetic drift. This change happens over ...

, specifically how they developed into new species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

by escaping environmental disadvantages and moving into new habitats. He developed a theory of the "taxon cycle Taxon cycles refer to a biogeographical theory of how species evolve through range expansions and contractions over time associated with adaptive shifts in the ecology and morphology of species. The taxon cycle concept was explicitly formulated by ...

".

In collaboration with mathematician William H. Bossert, Wilson developed a classification of pheromones

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavi ...

based on insect communication patterns. In the 1960s, he collaborated with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur

Robert Helmer MacArthur (April 7, 1930 – November 1, 1972) was a Canadian-born American ecologist who made a major impact on many areas of community and population ecology. He is considered to be one of the founders of ecology.

Early life ...

in developing the theory of species equilibrium. In the 1970s he and biologist Daniel S. Simberloff tested this theory on tiny mangrove islets in the Florida Keys. They eradicated all insect species and observed the repopulation Repopulation is the phenomenon of increasing the numerical size of human inhabitants or organisms of a particular species after they had almost gone extinct.

Organisms

An example of an organism that has repopulated after being on the brink of extin ...

by new species. Wilson and MacArthur's book ''The Theory of Island Biogeography

''The Theory of Island Biogeography'' is a 1967 book by the ecologist Robert MacArthur and the biologist Edward O. Wilson. It is widely regarded as a seminal work in island biogeography and ecology. The Princeton University Press reprinted the b ...

'' became a standard ecology text.

In 1971, he published ''The Insect Societies'', which argued that insect behavior and the behavior of other animals are influenced by similar evolutionary pressures. In 1973, Wilson was appointed the curator of entomology at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology

The Museum of Comparative Zoology (formally the Agassiz Museum of Comparative Zoology and often abbreviated to MCZ) is a zoology museum located on the grounds of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It is one of three natural-history r ...

. In 1975, he published the book '' Sociobiology: The New Synthesis'' applying his theories of insect behavior to vertebrates, and in the last chapter, to humans. He speculated that evolved and inherited tendencies were responsible for hierarchical social organization among humans. In 1978 he published '' On Human Nature'', which dealt with the role of biology in the evolution of human culture and won a Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

for General Nonfiction.

Wilson was named the Frank B. Baird Jr., Professor of Science in 1976 and, after he retired from Harvard in 1996, he became the Pellegrino University Professor Emeritus.

In 1981 after collaborating with biologist Charles Lumsden, he published ''Genes, Mind and Culture'', a theory of gene-culture coevolution. In 1990 he published ''The Ants

''The Ants'' is a zoology textbook by the German entomologist Bert Hölldobler and the American entomologist E. O. Wilson, first published in 1990. It won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 1991.

Contents

This book is primarily aimed a ...

'', co-written with zoologist Bert Hölldobler

Berthold Karl Hölldobler BVO (born 25 June 1936) is a German zoologist, sociobiologist and evolutionary biologist who studies evolution and social organization in ants. He is the author of several books, including '' The Ants'', for which he ...

, winning his second Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

In the 1990s, he published ''The Diversity of Life'' (1992); an autobiography, ''Naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

'' (1994); and '' Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge'' (1998) about the unity of the natural and social sciences. Wilson was praised for his environmental advocacy, and his secular-humanist and deist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

ideas pertaining to religious and ethical matters.

Wilson was characterized by several titles during his career, including the "father of biodiversity", "ant man", and "Darwin's heir". In a PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

interview, David Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and writer. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Studios Natural History Unit, the nine nature d ...

described Wilson as "a magic name to many of us working in the natural world, for two reasons. First, he is a towering example of a specialist, a world authority. Nobody in the world has ever known as much as Ed Wilson about ants. But, in addition to that intense knowledge and understanding, he has the widest of pictures. He sees the planet and the natural world that it contains in amazing detail but extraordinary coherence".

Disagreement with Richard Dawkins

Althoughevolutionary biologist

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes such as natural selection, common descent, and speciation that produced the diversity of life on Earth. In the 1930s, the discipline of evolutionary biol ...

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, zoologist, science communicator and author. He is an Oxford fellow, emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford, and was Simonyi Professor for the Publ ...

defended Wilson during the so-called " sociobiology debate", a disagreement between them arose over the theory of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, resulting in certai ...

. The disagreement began in 2012 when Dawkins wrote a critical review of Wilson's book '' The Social Conquest of Earth'' in ''Prospect Magazine

''Prospect'' is a monthly British general-interest magazine, specialising in politics, economics and current affairs. Topics covered include British and other European, as well as US politics, social issues, art, literature, cinema, science, th ...

''. In the review, Dawkins criticized Wilson for rejecting kin selection and for supporting group selection

Group selection is a proposed mechanism of evolution in which natural selection acts at the level of the group, instead of at the level of the individual or gene.

Early authors such as V. C. Wynne-Edwards and Konrad Lorenz argued that the beha ...

, labeling it "bland" and "unfocused", and he wrote that the book's theoretical errors were "important, pervasive, and integral to its thesis in a way that renders it impossible to recommend". Wilson responded in the same magazine and wrote that Dawkins made "little connection to the part he criticizes" and accused him of engaging in rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

.

In 2014, Wilson said in an interview, "There is no dispute between me and Richard Dawkins and there never has been, because he's a journalist, and journalists are people that report what the scientists have found and the arguments I've had have actually been with scientists doing research". Dawkins responded in a tweet: "I greatly admire EO Wilson & his huge contributions to entomology, ecology, biogeography, conservation, etc. He's just wrong on kin selection" and later added, "Anybody who thinks I'm a journalist who reports what other scientists think is invited to read ''The Extended Phenotype

''The Extended Phenotype'' is a 1982 book by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, in which the author introduced a biological concept of the same name. The book's main idea is that phenotype should not be ''limited'' to biological proces ...

''". Biologist Jerry Coyne

Jerry Allen Coyne (born December 30, 1949) is an American biologist and skeptic known for his work on speciation and his commentary on intelligent design. A professor emeritus at the University of Chicago in the Department of Ecology and Evolu ...

wrote that Wilson's remarks were "unfair, inaccurate, and uncharitable". In 2021, in an obituary

An obituary (wikt:obit#Etymology 2, obit for short) is an Article (publishing), article about a recently death, deceased person. Newspapers often publish obituaries as Article (publishing), news articles. Although obituaries tend to focus on p ...

to Wilson, Dawkins stated that their dispute was "purely scientific". Dawkins wrote that he stands by his critical review and doesn't regret "its outspoken tone", but noted that he also stood by his "profound admiration for Professor Wilson and his life work".

Support of J. Philippe Rushton

Prior to Wilson's death, his personal correspondences were donated to theLibrary of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

at the library's request. Following his death, several articles were published discussing the discrepancy between Wilson's legacy as a champion of biogeography and conservation biology and his support of scientific racist pseudoscientist J. Philippe Rushton over several years. Rushton was a controversial psychologist at the University of Western Ontario

The University of Western Ontario (UWO; branded as Western University) is a Public university, public research university in London, Ontario, Canada. The main campus is located on of land, surrounded by residential neighbourhoods and the Thame ...

, who later headed the Pioneer Fund

The Pioneer Fund is an American non-profit foundation established in 1937 "to advance the scientific study of heredity and human differences". The organization has been described as racist and white supremacist in nature. The Southern Pover ...

.

From the late 1980s to the early 1990s, Wilson wrote several emails to Rushton's colleagues defending Rushton's work in the face of widespread criticism for scholarly misconduct, misrepresentation of data, and confirmation bias, all of which were allegedly used by Rushton to support his personal ideas on race. Wilson also sponsored an article written by Rushton in ''PNAS

''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America'' (often abbreviated ''PNAS'' or ''PNAS USA'') is a peer-reviewed multidisciplinary scientific journal. It is the official journal of the National Academy of S ...

'', and during the review process, Wilson intentionally sought out reviewers for the article who he believed would likely already agree with its premise. Wilson kept his support of Rushton's racist ideologies behind-the-scenes so as to not draw too much attention to himself or tarnish his own reputation. Wilson responded to another request from Rushton to sponsor a second PNAS article with the following: "You have my support in many ways, but for me to sponsor an article on racial differences in the PNAS would be counterproductive for both of us." Wilson also remarked that the reason Rushton's ideologies were not more widely supported is because of the "... fear of being called racist, which is virtually a death sentence in American academia if taken seriously. I admit that I myself have tended to avoid the subject of Rushton's work, out of fear."

In 2022, the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation issued a statement rejecting Wilson's support of Rushton and racism, on behalf of the board of directors and staff.

Work

''Sociobiology: The New Synthesis'', 1975

Wilson used sociobiology and evolutionary principles to explain the behavior of social insects and then to understand the social behavior of other animals, including humans, thus establishing sociobiology as a new scientific field. He argued that all animal behavior, including that of humans, is the product ofheredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

, environmental stimuli, and past experiences, and that free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

is an illusion. He referred to the biological basis of behavior as the "genetic leash".E. O. Wilson, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, New York, Knopf, 1998. The sociobiological view is that all animal social behavior is governed by epigenetic

In biology, epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that happen without changes to the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix ''epi-'' (ἐπι- "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "on top of" or "in ...

rules worked out by the laws of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. This theory and research proved to be seminal, controversial, and influential.

Wilson argued that the unit of selection

A unit of selection is a biological entity within the hierarchy of biological organization (for example, an entity such as: a self-replicating molecule, a gene, a cell, an organism, a group, or a species) that is subject to natural selection. ...

is a gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

, the basic element of heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

. The ''target'' of selection is normally the individual who carries an ensemble of genes of certain kinds. With regard to the use of kin selection

Kin selection is a process whereby natural selection favours a trait due to its positive effects on the reproductive success of an organism's relatives, even when at a cost to the organism's own survival and reproduction. Kin selection can lead ...

in explaining the behavior of eusocial

Eusociality ( Greek 'good' and social) is the highest level of organization of sociality. It is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative brood care (including care of offspring from other individuals), overlapping generations wit ...

insects, the "new view that I'm proposing is that it was group selection

Group selection is a proposed mechanism of evolution in which natural selection acts at the level of the group, instead of at the level of the individual or gene.

Early authors such as V. C. Wynne-Edwards and Konrad Lorenz argued that the beha ...

all along, an idea first roughly formulated by Darwin."

Sociobiological research was at the time particularly controversial with regard to its application to humans. The theory established a scientific argument for rejecting the common doctrine of tabula rasa

''Tabula rasa'' (; Latin for "blank slate") is the idea of individuals being born empty of any built-in mental content, so that all knowledge comes from later perceptions or sensory experiences. Proponents typically form the extreme "nurture" ...

, which holds that human beings are born without any innate

{{Short pages monitor

Curriculum vitae

E.O. Wilson Foundation

* Review of '' The Social Conquest of Earth'' * *

E.O. Wilson Biophilia Center

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wilson, E. O. 1929 births 2021 deaths 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American zoologists 21st-century American male writers 21st-century American non-fiction writers 21st-century American novelists 21st-century American zoologists American autobiographers American conservationists American deists American ecologists American entomologists American humanists American male non-fiction writers American male novelists American naturalists American non-fiction environmental writers American science writers American skeptics Biogeographers American critics of religions Entomological writers American ethologists American evolutionary biologists Fellows of the Ecological Society of America Foreign members of the Royal Society Harvard University alumni Harvard University faculty Human evolution theorists Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Myrmecologists National Medal of Science laureates Neutral theory Novelists from Alabama Novelists from Massachusetts American philosophers of social science Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction winners People involved in race and intelligence controversies Secular humanists Sociobiologists American sustainability advocates University of Alabama alumni Writers about activism and social change Writers about religion and science Writers from Birmingham, Alabama Members of the American Philosophical Society

Books

* *Journals

* *Newspapers

*External links

Curriculum vitae

E.O. Wilson Foundation

* Review of '' The Social Conquest of Earth'' * *

E.O. Wilson Biophilia Center

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wilson, E. O. 1929 births 2021 deaths 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American zoologists 21st-century American male writers 21st-century American non-fiction writers 21st-century American novelists 21st-century American zoologists American autobiographers American conservationists American deists American ecologists American entomologists American humanists American male non-fiction writers American male novelists American naturalists American non-fiction environmental writers American science writers American skeptics Biogeographers American critics of religions Entomological writers American ethologists American evolutionary biologists Fellows of the Ecological Society of America Foreign members of the Royal Society Harvard University alumni Harvard University faculty Human evolution theorists Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Myrmecologists National Medal of Science laureates Neutral theory Novelists from Alabama Novelists from Massachusetts American philosophers of social science Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction winners People involved in race and intelligence controversies Secular humanists Sociobiologists American sustainability advocates University of Alabama alumni Writers about activism and social change Writers about religion and science Writers from Birmingham, Alabama Members of the American Philosophical Society