Edward Littleton, 1st Baron Hatherton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

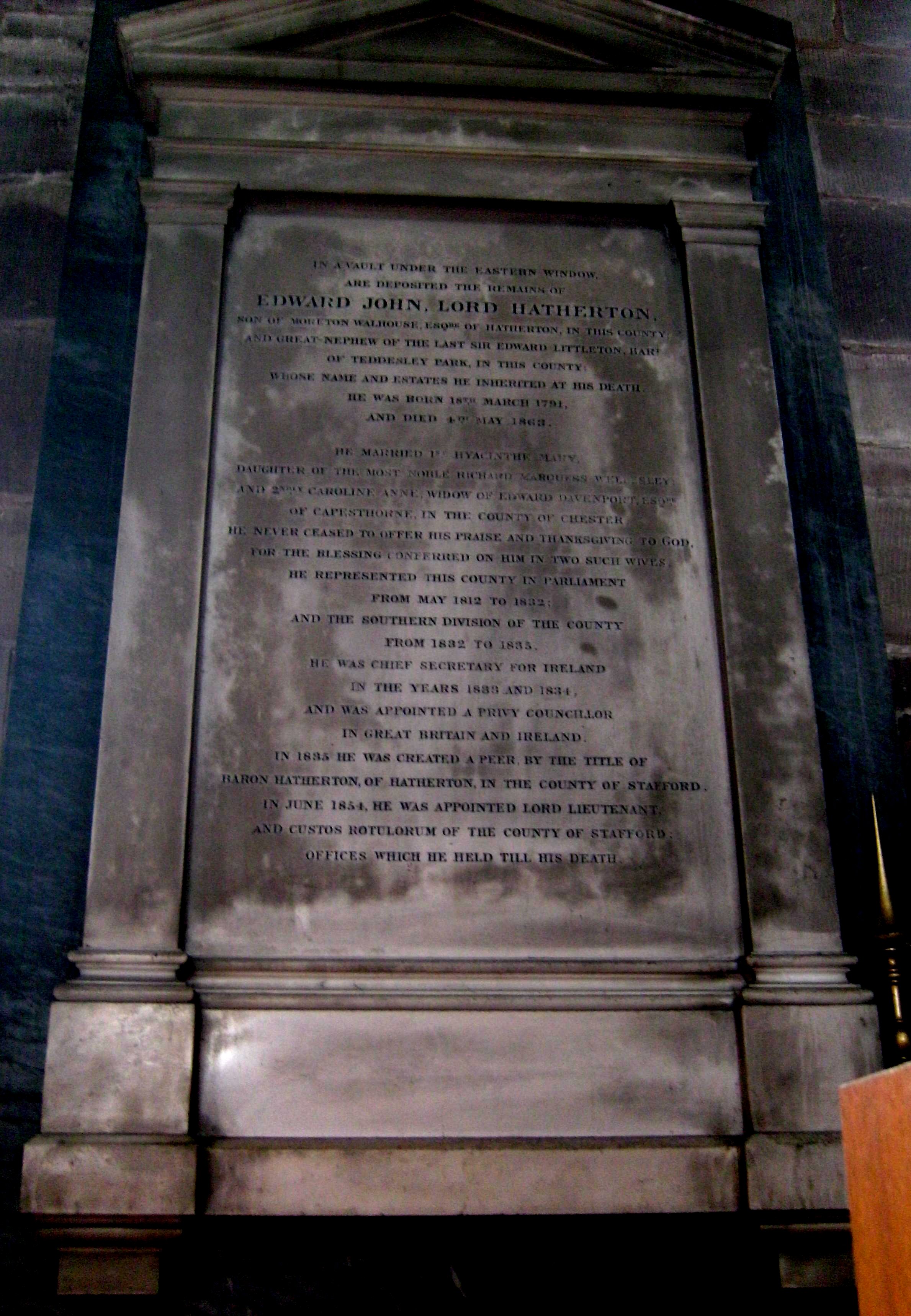

Edward John Littleton, 1st Baron Hatherton PC, FRS (18 March 17914 May 1863), was a British politician from the extended Littleton/Lyttelton family, of first the

Littleton was born Edward Walhouse, and was educated at

Littleton was born Edward Walhouse, and was educated at

Baron Hatherton at Cracrofts peerage

He died at his Staffordshire residence, Teddesley Hall, in May 1863, aged 72, and was buried, with his first wife and daughter, at

Canningite

Canningites were a faction of British Tories in the first decade of the 19th century through the 1820s who were led by George Canning. The Canningites were distinct within the Tory party because they favoured Catholic emancipation and free trad ...

Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

and later the Whigs. He had a long political career, active in each of the Houses of Parliament in turn over a period of forty years. He was closely involved in a number of major reforms, particularly Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

, the Truck Act of 1831, the Parliamentary Boundaries Act 1832

The Parliamentary Boundaries Act 1832 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which defined the parliamentary divisions (constituencies) in England and Wales required by the Reform Act 1832. The boundaries were largely those recommen ...

and the Municipal Corporations Act 1835

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 (5 & 6 Will 4 c 76), sometimes known as the Municipal Reform Act, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in the incorporated boroughs of England and Wales. The legisl ...

. Throughout his career he was actively concerned with the Irish question

The Irish question was the issue debated primarily among the British government from the early 19th century until the 1920s of how to respond to Irish nationalism and the calls for Irish independence.

The phrase came to prominence as a result ...

and he was Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant", from the early 19th century un ...

between 1833 and 1834.

Hatherton was also a major Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

landowner, farmer and businessman. As heir to two family fortunes, he had large holdings in agricultural and residential property, coal mines, quarries and brick works, mainly concentrated around Penkridge

Penkridge ( ) is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in South Staffordshire, South Staffordshire District in Staffordshire, England. It is to the south of Stafford, north of Wolverhampton, west of Cannock and east of Telford. ...

, Cannock

Cannock () is a town in the Cannock Chase district in the county of Staffordshire, England. It had a population of 29,018. Cannock is not far from the nearby towns of Walsall, Burntwood, Stafford and Telford. The cities of Lichfield and Wolverh ...

and Walsall

Walsall (, or ; locally ) is a market town and administrative centre in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands County, England. Historic counties of England, Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located north-west of Birmingham, east ...

.

Background and education

Littleton was born Edward Walhouse, and was educated at

Littleton was born Edward Walhouse, and was educated at Rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

and at Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the mi ...

. In 1812, he took the name of Littleton to inherit the large landed estates of his great-uncle Sir Edward Littleton, 4th and last of the Littleton Baronets

Three baronetcies have been created in the Baronetage of England for members of the Littleton or Lyttelton family. All three lines are descended from Thomas de Littleton, a noted 15th-century jurist. Despite differences in the spelling of the ...

, of Teddesley Hall

Teddesley Hall was a large Georgian English country house located close to Penkridge in Staffordshire, now demolished. It was the main seat firstly of the Littleton Baronets and then of the Barons Hatherton. The site today retains considerable ...

, near Penkridge

Penkridge ( ) is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in South Staffordshire, South Staffordshire District in Staffordshire, England. It is to the south of Stafford, north of Wolverhampton, west of Cannock and east of Telford. ...

, Staffordshire. In 1835, he also inherited large mineral and manufacturing interests in Walsall

Walsall (, or ; locally ) is a market town and administrative centre in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands County, England. Historic counties of England, Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located north-west of Birmingham, east ...

and Cannock

Cannock () is a town in the Cannock Chase district in the county of Staffordshire, England. It had a population of 29,018. Cannock is not far from the nearby towns of Walsall, Burntwood, Stafford and Telford. The cities of Lichfield and Wolverh ...

from his uncle, Edward Walhouse.

Political career

Political career, 1812–1833

Littleton also took over his great-uncle's parliamentary seat. From 1812 to 1832, he was Member of Parliament forStaffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

and then was the MP for the southern division of that county until 1835. He spent most of that time as a Canningite

Canningites were a faction of British Tories in the first decade of the 19th century through the 1820s who were led by George Canning. The Canningites were distinct within the Tory party because they favoured Catholic emancipation and free trad ...

Tory, but moved over to the Whigs after George Canning

George Canning (11 April 17708 August 1827) was a British Tory statesman. He held various senior cabinet positions under numerous prime ministers, including two important terms as Foreign Secretary, finally becoming Prime Minister of the Unit ...

's death in 1827.

In the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, Littleton was especially prominent as an advocate of Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

emancipation. In 1825, as a preliminary to a Catholic Relief Bill promoted by Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

, he introduced an Elective Franchise in Ireland Bill. The objective of this was, paradoxically, to raise the property qualification for Irish voters. However, its underlying aim was to end abuse of a distinctively Irish form of freehold, which had to be renewed by payment to the original landlord, and so allowed large landowners to create large numbers of compliant voters. Both the Relief and the Franchise Bills failed. After crossing the floor of the House to join the Whigs in 1827, Littleton voted for the Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

Bill that finally became law in 1829.

From this point, the style and content of his contributions changed completely. For almost twenty years he had been content generally to make short contributions, usually delivering himself of his considered opinions or changed notions (for he sometimes altered his initial stance during debate) in the chamber of the house in a few unmemorable phrases. From 1830 he became closely involved in committee work on important reforms. As his opinions became more radical, he adopted an increasingly trenchant and discursive style, speaking frequently in long, argued statements, laden with factual detail. On one day in September 1831, for example, he made eight speeches of varying length in the House. One of the important factors in this change of style and focus seems to have been his increasingly close contact with middle and working class opinion in the growing Staffordshire towns – Stoke on Trent

Stoke-on-Trent (often abbreviated to Stoke) is a city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Staffordshire, England, with an area of . In 2019, the city had an estimated population of 256,375. It is the largest settlement ...

, Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunian ...

and Walsall

Walsall (, or ; locally ) is a market town and administrative centre in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands County, England. Historic counties of England, Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located north-west of Birmingham, east ...

. He frequently presented petitions and deployed arguments and reports drawn directly from these disfranchised towns and people. As he became more combative and forensic in his contributions, he was increasingly regarded as a Radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

rather than merely a Whig.

After the 1830 General Election ended Tory domination, and brought in a minority Whig government under Earl Grey

Earl Grey is a title in the peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1806 for General Charles Grey, 1st Baron Grey. In 1801, he was given the title Baron Grey of Howick in the County of Northumberland, and in 1806 he was created Viscou ...

, Littleton took up the campaign against the truck system

Truck wages are wages paid not in conventional money but instead in the form of payment in kind (i.e. commodities, including goods and/or services); credit with retailers; or a money substitute, such as scrip, chits, vouchers or tokens. Truck ...

. This was the practice by which employees were forced to accept payment or advances in kind, often becoming effectively enslaved to the company store. First he presented numerous petitions against the system from workers in Staffordshire and Gloucestershire. He asked and obtained leave to introduce a bill against the truck system at the end of the year. The 1831 general election completely changed the electoral landscape, ushering in a reforming Whig ministry under Grey, and allowing Littleton to proceed with his bill with a fair certainty of success. Moving the vote on the bill in September 1831, he pointed out that "it was notorious that the universal feeling of the working classes was in favour of some attempt to put down this odious system." He summarised its main purpose simply as that "the workmen must be paid in money." Consolidating and extending numerous earlier acts on the subject, the Truck Act of 1831 (actually the Money Payment of Wages Act) was a landmark piece of social legislation, which was invoked as still relevant in Parliament as recently as 2003.

The campaign for the Truck Act had revealed an important weakness in Littleton's character that was to have major consequences for his career. To get the reform through, he had made the concession that Ireland be excluded from it for the time being. At one point he had let slip the unguarded comment that he did not care about Ireland. This was overheard by one of the members for Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

– presumably Lord George Beresford

Lord George Thomas Beresford GCH, PC (12 February 1781 – 26 October 1839) was an Anglo-Irish soldier, courtier and Tory politician. He served as Comptroller of the Household from 1812 to 1830.

Background

Beresford was the fourth son of Geo ...

, who was hated by the Radicals and Irish Repealers, and who proceeded to broadcast the remark. Littleton took up the challenge in Parliament and, accepting that the report of his comment was accurate, pointed out that it was reported entirely out of context. In fact, it was well known that he had been a strong proponent of Emancipation. However, the damage was done.

As the Truck Act passed into Law, Littleton was drafted into detailed work on the Great Reform Bill

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

, intended to create an entirely new system of parliamentary representation. The reform had two main thrusts: a simplification of the Franchise

Franchise may refer to:

Business and law

* Franchising, a business method that involves licensing of trademarks and methods of doing business to franchisees

* Franchise, a privilege to operate a type of business such as a cable television p ...

qualification and a complete redrawing of the Constituency

An electoral district, also known as an election district, legislative district, voting district, constituency, riding, ward, division, or (election) precinct is a subdivision of a larger State (polity), state (a country, administrative region, ...

boundaries to abolish the rotten boroughs

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electora ...

and pocket borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electorat ...

s. Littleton was appointed as an unpaid Commissioner on the latter task. Here his command of detail and forensic skills found a perfect outlet, as the reform involved careful research, the establishment of principles and their application to hundreds of varying local situations. He was determined that the reform should be based on the latest data about population sizes, not on the traditional status of settlements. He was formidably well informed and often sarcastic in debate, often tangling with John Wilson Croker

John Wilson Croker (20 December 178010 August 1857) was an Anglo-Irish statesman and author.

Life

He was born in Galway, the only son of John Croker, the surveyor-general of customs and excise in Ireland. He was educated at Trinity College Dubl ...

, a bitterly anti-Reform Irish Tory who sat for the rotten borough of Aldeburgh

Aldeburgh ( ) is a coastal town in the English county, county of Suffolk, England. Located to the north of the River Alde. Its estimated population was 2,276 in 2019. It was home to the composer Benjamin Britten and remains the centre of the int ...

. In his first major contribution in Committee, he said in reply to an ill-informed remark by Croker that: "his right hon. friend had displayed his want of acquaintance with the county of Stafford when he spoke of the village of Bilston. The village of Bilston, as his right hon. friend was facetiously pleased to style it, contained a population of not less than 14,000 or 15,000 souls.". He made similar contributions to uphold the importance of Wolverhampton, Walsall and Stoke, continually insisting on the principle that constituencies should represent communities and populations, not political or economic interests. He consistently appealed simultaneously to principles and facts, showing a ferocious interest in every region of the country, for example: "as one of the Commissioners upon whom was devolved the duty of fixing the limits of the new borough of Huddersfield, he felt himself called upon to state that, in performing that duty, he did not conceive himself bound to consider the extent of property which any individual might possess within the borough, or his political opinions." Ultimately, the Reform Bill as originally conceived proved unwieldy, and the boundary reform, with its mass of detail and numerous schedules was divided off into a second bill. Hence the "Reform Act of 1832" is really two separate acts: a Representation of the People Act and the Parliamentary Boundaries Act 1832

The Parliamentary Boundaries Act 1832 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which defined the parliamentary divisions (constituencies) in England and Wales required by the Reform Act 1832. The boundaries were largely those recommen ...

, which owed much of its effectiveness

Effectiveness is the capability of producing a desired result or the ability to produce desired output. When something is deemed effective, it means it has an intended or expected outcome, or produces a deep, vivid impression.

Etymology

The ori ...

to Littleton's work.

It is some measure of the regard in which he was held by parliamentary Radicals that in the Speaker election of January 1833, against his own wish, he was nominated by the Scottish MP Joseph Hume

Joseph Hume FRS (22 January 1777 – 20 February 1855) was a Scottish surgeon and Radical MP.Ronald K. Huch, Paul R. Ziegler 1985 Joseph Hume, the People's M.P.: DIANE Publishing.

Early life

He was born the son of a shipmaster James Hume ...

to become Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** I ...

of the first reformed House of Commons. He was seconded by Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

himself. Littleton spoke against his own nomination, expressing his confidence in the existing Speaker, Charles Manners-Sutton

Charles Manners-Sutton (17 February 1755 – 21 July 1828; called Charles Manners before 1762) was a bishop in the Church of England who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1805 to 1828.

Life

Manners-Sutton was the fourth son of Lord G ...

, a Tory member, and praising his "unexampled patience and urbanity". Littleton had voted for Manners-Sutton consistently since 1817. He correctly diagnosed his own nomination as a political protest and he did not consider the Speakership a party matter. O'Connell countered with a long speech denouncing Toryism, demanding a triumphal vindication of the Reform Act and refusing to withdraw the nomination. He regarded the nomination of Manners-Sutton "as another instance of that paltry truckling on the part of the present Administration towards their ancient enemies, which had already afforded such frequent subjects of complaint." Lord Althorp

John Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl Spencer, (30 May 1782 – 1 October 1845), styled Viscount Althorp from 1783 to 1834, was a British statesman

A statesman or stateswoman typically is a politician who has had a long and respected political care ...

, a fellow Radical, supported Littleton's non-partisan view but William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restrain foreign ...

gave a bitterly partisan speech, claiming that the election of Manners-Sutton would be "an open declaration of war against the people of England." Much of the venom derived from an accompanying proposal to pay the Speaker a large pension. However, Manners-Sutton himself rose to reject the idea of a pension. A division was held on the proposal install Littleton in the Chair and it was defeated by 241 votes to 31: Littleton did not vote for himself. Littleton's nomination, though rejected by himself, had initiated an important constitutional debate, which established permanently in the reformed parliament the non-partisan character of the Speaker.

Chief Secretary for Ireland, 1833–1834

In May 1833 Littleton became chief secretary to theLord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the Kingdo ...

in the ministry of Earl Grey

Earl Grey is a title in the peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1806 for General Charles Grey, 1st Baron Grey. In 1801, he was given the title Baron Grey of Howick in the County of Northumberland, and in 1806 he was created Viscou ...

, with Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley

Richard Colley Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, (20 June 1760 – 26 September 1842) was an Anglo-Irish politician and colonial administrator. He was styled as Viscount Wellesley until 1781, when he succeeded his father as 2nd Earl of M ...

, Littleton's father-in-law, as Lord Lieutenant. The appointments met with the approval of Daniel O'Connell. However, Littleton was part of a shaky coalition of Whigs and Radicals. The Whigs were much more concerned with defending property rights and the position of the established church than the Radicals, who were prepared to sacrifice both if they perceived injustice. He was often forced to take positions which might normally have gone against his political instincts, and he also allowed his loose tongue to get him into further trouble.

The main point of conflict was the issue of Irish Tithes

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

. Incensed by the legal requirement to pay tithes to the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

, the Repealers had launched a campaign of refusal to pay among the mainly Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

(otherwise Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

) peasantry. This sporadically flared into violence in the Tithe War

The Tithe War ( ga, Cogadh na nDeachúna) was a campaign of mainly nonviolent civil disobedience, punctuated by sporadic violent episodes, in Ireland between 1830 and 1836 in reaction to the enforcement of tithes on the Roman Catholic majority ...

. Littleton was compelled by the alliance with Whigs to bring in a Tithe Arrears (Ireland) Bill, which set out some concessions in the payment terms but reaffirmed the government's determination to impose tithes on Ireland for the foreseeable future. It was accompanied by one of the many Irish Coercion bills which partially suspended civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

in Ireland to suppress rural violence.

Initially, Littleton seemed to be steering a compromise course fairly successfully. On the one hand he portrayed the recovery of tithes as a painful necessity, while denouncing unwarranted and sometimes illegal police violence. However, this could not last. As early as 10 July, Littleton upset the Irish Repealers in the Commons. Feargus O'Connor

Feargus Edward O'Connor (18 July 1796 – 30 August 1855) was an Irish Chartist leader and advocate of the Land Plan, which sought to provide smallholdings for the labouring classes. A highly charismatic figure, O'Connor was admired for his ...

, one of the most radical of the Irish party, brought forward a petition demanding the repeal of the Acts of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 (sometimes incorrectly referred to as a single 'Act of Union 1801') were parallel acts of the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Irela ...

. Littleton responded that: "That was a proposition so utterly devoid of commonsense, that it was scarcely necessary for him to say, that when it was brought forward, it would be met by the most strenuous opposition. He need scarcely use such strong language, for the proposition was so extremely absurd — so opposed to the feelings and interests of both Englishmen and Irishmen, that any strenuous exertion would be totally unnecessary, in order to ensure it a signal defeat." This was clearly far beyond what was necessary to dissociate himself from O'Connor.

However, there was no real chance of repeal going through at that point. Rather hastily he made a compact with O'Connell on the assumption that the new coercion act could not contain certain repressive clauses which were part of the old act. The clauses, however, were inserted; O'Connell charged Littleton with deception; and in July 1834 Grey, Viscount Althorp and the Irish secretary resigned. The two latter were induced to serve under the new premier, Lord Melbourne

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, (15 March 177924 November 1848), in some sources called Henry William Lamb, was a British Whig politician who served as Home Secretary (1830–1834) and Prime Minister (1834 and 1835–1841). His first pre ...

, and they remained in office until Melbourne was dismissed in November 1834.

Career in House of Lords, 1835–1863

In February 1835, Littleton won re-election to the House of Commons as member for Staffordshire Southern – part of a Whig victory that returnedMelbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

to power. Shortly afterwards, the new administration raised Littleton to the peerage as Baron Hatherton, of Hatherton in the County of Stafford. Hatherton took his title from a Staffordshire village which at that time was an exclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

of Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunian ...

, where Littleton owned Hatherton Hall Hatherton may refer to:

* Hatherton, Cheshire, England

* Hatherton, Staffordshire, England

** The derelict Hatherton Canal

** Baron Hatherton

* Hatherton Glacier

Hatherton Glacier is a large glacier flowing from the Antarctic polar plateau gene ...

, a country house that formed part of the Walhouse inheritance. Since he was now constitutionally barred from serving as a member of the House of Commons, his seat had to be contested again in a by-election in May, won by a fellow Whig, Sir Francis Goodricke.

As a peer, Hatherton was automatically a member of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

and able to make a contribution to parliamentary debate and processes. This he did until the year before his death, although his contributions tailed off considerably after his Address in Answer to the Speech from the Throne

A speech from the throne, or throne speech, is an event in certain monarchies in which the reigning sovereign, or a representative thereof, reads a prepared speech to members of the nation's legislature when a session is opened, outlining th ...

in 1847, perhaps for family reasons.

For several years after his elevation to the peerage, Hatherton was closely involved in campaigns to extend the political reforms of the Whig administration. Most important of these initially was municipal reform. Hatherton presented numerous petitions, and took up the cause of several small towns, in the campaign preceding the Municipal Corporations Act 1835

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 (5 & 6 Will 4 c 76), sometimes known as the Municipal Reform Act, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in the incorporated boroughs of England and Wales. The legisl ...

. He served on the Lords committee on the bill and was often acerbic in debate, much as he had been on earlier reforms. Key to the measure was the enfranchisement of ratepayers

Rates are a type of property tax system in the United Kingdom, and in places with systems deriving from the British one, the proceeds of which are used to fund local government. Some other countries have taxes with a more or less comparable role ...

. When the Tory peers rallied to the cause of the freemen, a rather flexible class who dominated the electorate in many towns and cities, Hatherton observed caustically that:

When a similar measure was proposed for Ireland in 1838, Hatherton defended it trenchantly in the Lords, taking particular exception to attempts to tamper with the franchise. In a substantial, detailed speech he used his old tactic of marshalling demographic and financial detail to swamp rhetorical argument. Everywhere he perceived possible corruption, he entered his name in the lists against it. So in 1837, for example, we find his name among the six radical Lords wanting to pursue an urgent enquiry into the statutes of the Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of Oxford and Cambridge, the two oldest, wealthiest, and most famous universities in the United Kingdom. The term is used to refer to them collectively, in contrast to other British universities, and more broadly to de ...

colleges, on the grounds, among others, that the colleges were "of very ancient foundation, and many of their statutes, contemplating a state of society very different from the present, and a religion other than that now established, are totally inapplicable to the present times, and impossible to be observed."

Another cause was the struggle against the Church Rate

The church rate was a tax formerly levied in each parish in England and Ireland for the benefit of the Church of England parish church, parish church. The rates were used to meet the costs of carrying on divine service, repairing the fabric of the ...

, the compulsory levy for maintenance of Anglican parish churches that so offended both Catholic and Protestant Dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, and ...

s. The Church Rate agitation was part of a wider campaign for reforms of position of the established Church, which broke its monopoly over the recording of births, marriages and deaths in 1837, but poor rates were not made voluntary until 1868, five years after Hatherton's death. In fact, after this disappointment, and especially in the early 1840s, a period of Tory dominance that brought Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

to power, Hatherton's contributions slackened for a time in number and in focus. Without a clear programme of government reforms to promote, he tended to moralise or equivocate.

Hatherton was always a zealous promoter of Lord's Day

The Lord's Day in Christianity is generally Sunday, the principal day of communal worship. It is observed by most Christians as the weekly memorial of the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who is said in the canonical Gospels to have been witnessed al ...

observance, a cause which united almost all the churches. Both Hatherton and his ecclesiastical allies were at least as concerned with the hours and conditions of the workers as with due decorum on a day of worship. Hatherton presented many petitions on the subject in the 1830s and in 1840 he focussed his attention on the demand for a law to stop Sunday traffic on the canals and railways. Hatherton had a major economic interest in canals, and the Hatherton Canal

The Hatherton Canal is a derelict branch of the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal in south Staffordshire, England. It was constructed in two phases, the first section opening in 1841 and connecting the main line to Churchbridge, from where ...

was only part of the network that served his mines and quarries in Staffordshire. He sought legislation to impose a solution on the canal owners, who would not agree among themselves to a holiday for their workers. This issue preoccupied him for the next two years, gradually shading into arguments about working conditions more generally.

Hatherton made a number of important speeches in the period leading up to Mines and Collieries Act 1842

The Mines and Collieries Act 1842 (c. 99), commonly known as the Mines Act 1842, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act forbade women and girls of any age to work underground and introduced a minimum age of ten for boys e ...

. As a coal-owner, his economic interests were even more closely involved than in the case of the canals. His economic liberalism was thus brought into conflict with his zeal for social reform. A Commission, headed by Lord Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (28 April 1801 – 1 October 1885), styled Lord Ashley from 1811 to 1851, was a British Tory politician, philanthropist, and social reformer. He was the eldest son of The 6th Earl of Shaftesbury ...

, had investigated conditions in the mines and its proposals for reform included prohibitions on female and child labour

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such e ...

underground. Hatherton found himself in the unusual and uncomfortable position of defending the status quo alongside Charles Vane, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, a Tory grandee hated in the mining areas of Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

and Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

. However, Hatherton claimed that conditions in the Midland coal mining areas were much better than in the north and portrayed the miners as an aristocracy of labour, with the child labourers as "apprentices". Partly through his intransigence, the age lower limit for boys to work underground was set at ten. On the other hand, Hatherton welcomed a ban on women working in the mines and defended against all attempts to dilute it.

The Railway Mania

Railway Mania was an instance of a stock market bubble in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in the 1840s. It followed a common pattern: as the price of railway shares increased, speculators invested more money, which further incre ...

of the 1840s saw Littleton trying to get to grips with the pace of modernisation. Early in 1845 he spoke at length in support of a petition from the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal

The Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal is a navigable narrow canal in Staffordshire and Worcestershire in the English Midlands. It is long, linking the River Severn at Stourport in Worcestershire with the Trent and Mersey Canal at Haywoo ...

Company, attacking predatory pricing by railways. A little later he encouraged people affected by railway development to group together in corporate bodies to defend their joint interests. and speaking in defence of the coastal trade in coal. The following year, however, he was showing a very positive attitude and was advocating a streamlined system for dealing with railway development. In fact, he had informed himself sufficiently to hazard the opinion that broad gauge

A broad-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge (the distance between the rails) broader than the used by standard-gauge railways.

Broad gauge of , commonly known as Russian gauge, is the dominant track gauge in former Soviet Union (CIS ...

was the future.

Proposed changes to the Game Act 1831

The Game Act 1831 (1 & 2 Will 4 c 32) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which was passed to protect game birds by establishing a close season when they could not be legally taken. The Act also established the need for game licenc ...

also gave him a chance to advertise himself as a modern and improving landlord. He proposed removing hares from the status of game, so that tenants might eliminate them from their land and boasted of his near-extermination of hares and rabbits on his own estates: "he could scarcely exaggerate the satisfaction which had resulted from that course, both to himself and to his tenants."

However, the Irish Question was again coming to dominated debate and it had never ceased to be one of Hatherton's major concerns. During the 1830s he had spoken often on Irish matters, steering a tortuous path. On the one hand he supported most of the causes of equality and social reform dear to Irish nationalists. In 1836, for example, we find him defending the suppression of Orange lodges and denouncing the poor representation of Catholics on public bodies. However, he also supported coercive Government measures to suppress disorder, often taking a hardline position. In 1844 Hatherton promoted a reform popular with Irish Catholics: the Charitable Bequests (Ireland) Act, which created a corporate body to accept bequests in favour of the Irish clergy. In so doing, he seized the opportunity to attack the poor provision for Catholic clerical education. This helped stoke the agitation that led to the Maynooth Grant

The Maynooth Grant was a cash grant from the British government to a Catholic seminary in Ireland. In 1845, the Conservative Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, sought to improve the relationship between Catholic Ireland and Protestant Britain by in ...

of 1845, with its disastrously divisive consequences for the Tory party.

However, the disaster of the Great Famine soon pushed even these important issues to the periphery. Peel recognised that the famine could not be ended while the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They were ...

, major protective tariffs on food imports, continued in force. Although it had never dominated Hatherton's radicalism, he had long been loyal to the anti-Corn Law cause and had spoken most effectively on the subject when he presented no less than six petitions from Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunian ...

in 1839 There was never any doubt of his support for the repeal of the laws in 1846, a volte-face for the Tory party that split it more disastrously and more permanently than Maynooth and brought down Peel's government. The minority Whig government of John Russell, 1st Earl Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

dealt with the famine, as closely as possible according to laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. ...

principles, through the administrator Charles Trevelyan. He was so preoccupied with a market solution that he restricted relief through public works and forced millions to starve or emigrate.

From August 1846, Parliament was continuously prorogued and the government avoided facing its critics. As 1847 began, the government was forced to think again, and decided to bring in soup kitchen

A soup kitchen, food kitchen, or meal center, is a place where food is offered to the Hunger, hungry usually for free or sometimes at a below-market price (such as via coin donations upon visiting). Frequently located in lower-income neighborhoo ...

s and outdoor relief

Outdoor relief, an obsolete term originating with the Elizabethan Poor Law (1601), was a program of social welfare and poor relief. Assistance was given in the form of money, food, clothing or goods to alleviate poverty without the requirement t ...

. Parliament was reconvened on 19 January and the government's revised strategy sketchily outlined to in Speech from the Throne

A speech from the throne, or throne speech, is an event in certain monarchies in which the reigning sovereign, or a representative thereof, reads a prepared speech to members of the nation's legislature when a session is opened, outlining th ...

that gave Ireland prominence but wandered across such topics as the marriage of the Spanish Infanta

''Infante'' (, ; f. ''infanta''), also anglicised as Infant or translated as Prince, is the title and rank given in the Iberian kingdoms of Spain (including the predecessor kingdoms of Aragon, Castile, Navarre, and León) and Portugal to th ...

, and problems in Poland and Argentina. As a senior Whig peer, Hatherton rose to make a formal Address in Answer. He immediately stated that the condition of Ireland was topic of "all-absorbing importance" and went on to give a long speech in which all other matters were relegated to a formal mention at the end. He stressed the vast scale of famine and the inadequacy of government attempts to tackle it. He welcomed public works programmes but declared that if they were now pointless or impractical, other means of relieving the famine had to be found. Hatherton stated that his purpose was to "implore their Lordships, in considering this question, to make the case of Ireland their own" and demanded the government treat it exactly as if it had happened in England. He asked the peers to consider what would have been their response if some pest had destroyed England's cotton imports: would they leave Manchester to its own devices? He demanded abolition of all residual restrictions on food imports. The government was proposing to finance relief from future taxes on Ireland. Hatherton rejected this explicitly. What would be the response to a famine in England: would Parliament really expect English landlords to pay thee entire cost of relief. Hatherton made clear that he was not speaking on the government's behalf:

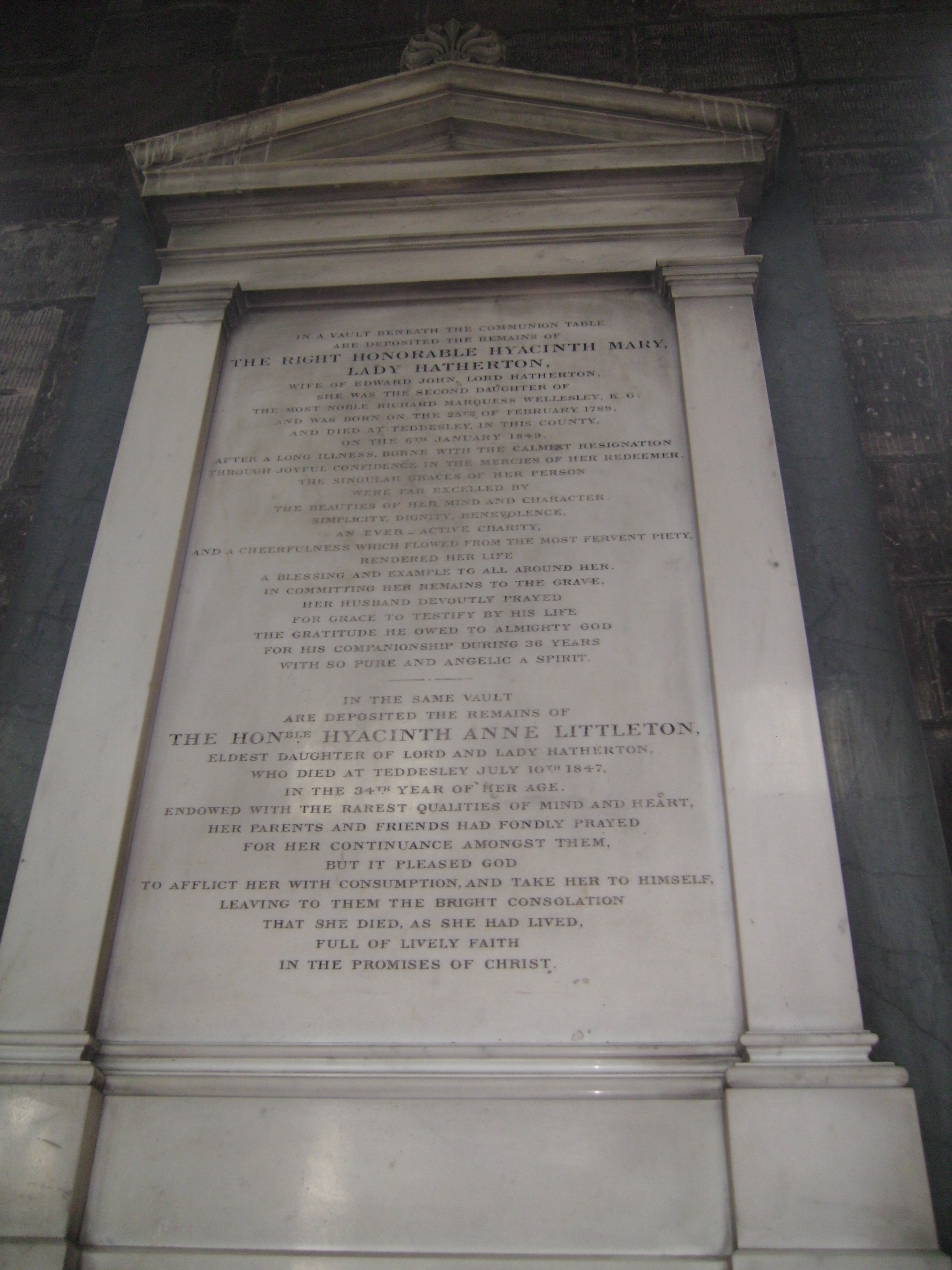

His speech, which had departed far from the usual formal paean to the monarch's words and criticised the central pillar of government policy, elicited considerable outrage. It was the peak of his career as a working peer. From this point, his contributions became briefer and less frequent. This roughly corresponds to the onset of important family bereavements. Hyacinth Anne, his daughter had died in July 1847 after a long struggle against tuberculosis. His wife, Hyacinthe Mary, too became seriously ill, dying at the beginning of 1849. Hatherton served as Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire between 1854 and 1863an honorific local post with considerable ceremonial duties that perhaps filled his time as he himself became less able to travel. His last contribution to debate, in 1852, was characteristically trenchant attack on the arrogance of the telegraph companies who inconvenienced residents without notice, and a demand that they pay compensation.

Business and property interests

Hatherton was a very wealthy man, partly because of his inherited interests, and partly because of his own business activities. The Littleton inheritance brought almost the whole of the manor ofPenkridge

Penkridge ( ) is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in South Staffordshire, South Staffordshire District in Staffordshire, England. It is to the south of Stafford, north of Wolverhampton, west of Cannock and east of Telford. ...

, as well as the former Penkridge deanery manor, and other estates in that area – land accruing in the hands of the Littletons since 1502. The Walhouse inheritance brought large coal mines in Cannock

Cannock () is a town in the Cannock Chase district in the county of Staffordshire, England. It had a population of 29,018. Cannock is not far from the nearby towns of Walsall, Burntwood, Stafford and Telford. The cities of Lichfield and Wolverh ...

and Walsall

Walsall (, or ; locally ) is a market town and administrative centre in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands County, England. Historic counties of England, Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located north-west of Birmingham, east ...

, as well as extractive works supplying the construction industry, including sandstone and limestone quarries, brickyards, gravel pits and sand pits. This made him immensely influential as a landlord and employer across a large tract of south and central Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

.

A listing of his economic interests in 1862, the year before his death, includes:

* Teddesley Hall

Teddesley Hall was a large Georgian English country house located close to Penkridge in Staffordshire, now demolished. It was the main seat firstly of the Littleton Baronets and then of the Barons Hatherton. The site today retains considerable ...

, Woods and Farm; Hatherton Hall, Pillaton Gardens, Teddesley and Hatherton Estate Rentals – all in his own occupation

* 288 holdings in the following townships: Abbots Bromley, Acton Trussell, Bednall, Beaudesert and Longdon, Bosoomoor, Congreve, Coppenhall, Cannock, Drayton, Dunston, Huntington, Hatherton, Linell, Levedale, Longridge, Otherton, Pipe Ridware, Penkridge, Pillaton, Preston, Stretton, Saredon and Shareshill, Teddesley, Water Eaton, Wolgarston

* Walsall Estate Rental

* 236 holdings, in Walsall

* Royalties from mineral extraction at Hatherton Colliery, Bloxwich; Hatherton Colliery, Great Wyrley; Serjeants Hill Colliery, Walsall; Hatherton Lime Works, Walsall; Walsall Old Lime Works; Paddock Brickyard, Walsall; Sutton Road Brickyard, Walsall; Serjeants Hill Brickyard, Walsall; Butts Brickyard, Walsall; Old Brooks Brickyard, Walsall; Long House Brickyard, Cannock; Rumer Hill Brickyard, Cannock; Penkridge Brickyard; Wolgarstone Stone Quarry, Teddesley; Wood Bank and Quarry Heath Stone Quarries, Teddesley; Gravel Pit, Huntington; Sand Pit at Hungry Hill, Teddesley. Also land rentals from some of the mine properties.

* Tithes from 579 occupiers in Hatherton, Cannock, Leacroft, Hednesford, Cannock Wood, Wyrley, Saredon, Shareshill, Penkridge, Congreve, Mitton, Whiston, Rodbaston, Coppenhall, Dunston, Bloxwich, Walsall Wood.

Although most of Hatherton's income from agriculture came in the form of rents and tithes, he was also a considerable farmer on his own account. He drained and developed a large area of land to expand the Home farm (agriculture), home farm at Teddesley into a holding of some 1700 acres. Here he had 200 head of cattle and 2000 sheep. 700 acres were under cultivation, using a four-course crop rotation. By 1860, he had established a free agricultural college at Teddesley for 30 boys, many the sons of tenants. The boys worked for part of each day on the estate as well as receiving practical and formal instruction.

New Zealand Company

In 1825 Littleton was a director of the New Zealand Company, a venture chaired by the wealthy John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, John George Lambton, Whigs (British political party), Whig MP (and later 1st Earl of Durham), that made the first attempt to colonise New Zealand.Family

Lord Hatherton married Hyacinthe Mary Wellesley, eldest illegitimate daughter ofRichard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley

Richard Colley Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, (20 June 1760 – 26 September 1842) was an Anglo-Irish politician and colonial administrator. He was styled as Viscount Wellesley until 1781, when he succeeded his father as 2nd Earl of M ...

and Hyacinthe-Gabrielle Roland, in October 1812. One of the governesses to their children (1821-1825) was Anna Brownell Jameson, later an author and art historian.

Lady Hatherton died after a long illness on 6 January 1849. A daughter, Hyacinth Anne, had already died in 1847. In 1852 Hatherton married Caroline Davenport, née Hurt, (1810–1897) of Wirksworth, Derbyshire.He died at his Staffordshire residence, Teddesley Hall, in May 1863, aged 72, and was buried, with his first wife and daughter, at

Penkridge

Penkridge ( ) is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in South Staffordshire, South Staffordshire District in Staffordshire, England. It is to the south of Stafford, north of Wolverhampton, west of Cannock and east of Telford. ...

parish church. He was succeeded in the barony by his son Edward Littleton, 2nd Baron Hatherton, Edward.

References

Further reading

* Reeve, H. (ed.) ''Memoirs and Correspondence relating to Political Occurrences, June–July 1834''. London : 1872. * Spencer Walpole, Walpole, Sir Spencer. ''History of England'', vol. iii. (1890). *Kidd, Charles, Williamson, David (editors). ''Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage'' (1990 edition). New York: St Martin's Press, 1990. * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hatherton, Edward Littleton, 1st Baron People educated at Rugby School Alumni of Brasenose College, Oxford Tory MPs (pre-1834), Littleton, Edward Whig (British political party) MPs, Littleton, Edward UK MPs 1818–1820, Littleton, Edward UK MPs 1820–1826, Littleton, Edward UK MPs 1826–1830, Littleton, Edward UK MPs 1830–1831, Littleton, Edward UK MPs 1831–1832, Littleton, Edward UK MPs 1832–1835, Littleton, Edward UK MPs who were granted peerages, Littleton, Edward Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies, Littleton, Edward Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Lord-Lieutenants of Staffordshire 1791 births 1863 deaths Fellows of the Royal Society Members of the Privy Council of Ireland Chief Secretaries for Ireland Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Lyttelton family, Edward Peers of the United Kingdom created by William IV