Edward Hallett Carr on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Hallett Carr (28 June 1892 – 3 November 1982) was a British historian, diplomat, journalist and

In 1937, Carr visited the Soviet Union for a second time, and was impressed by what he saw. During his visit, Carr may have inadvertently caused the death of his friend, Prince

In 1937, Carr visited the Soviet Union for a second time, and was impressed by what he saw. During his visit, Carr may have inadvertently caused the death of his friend, Prince  In ''The Twenty Year's Crisis'', Carr divided thinkers on international relations into two schools, which he labelled the utopians and the realists. Reflecting his own disillusion with the League of Nations, Carr attacked as "utopians" those like

In ''The Twenty Year's Crisis'', Carr divided thinkers on international relations into two schools, which he labelled the utopians and the realists. Reflecting his own disillusion with the League of Nations, Carr attacked as "utopians" those like

''The Vices of Integrity''

p. 151 In May–June 1951, Carr delivered a series of speeches on British radio entitled ''The New Society'', that advocated a commitment to mass democracy, egalitarian democracy, and "public control and planning" of the economy. Carr was a reclusive man whom few knew well, but his circle of close friends included

After the war, Carr was a fellow and tutor in politics at

After the war, Carr was a fellow and tutor in politics at

online

* St. Clair-Sobell, James Review of ''A History of Soviet Russia: The Bolshevik Revolution 1917–1923'' pages 128–129 from ''International Journal'', Volume 8, Issue # 2, Spring 1953. * St. Clair-Sobell, James Review of ''A History of Soviet Russia: The Bolshevik Revolution 1917–1923'' pages 59–60 from ''International Journal'', Volume 9, Issue # 1, Winter 1954. * Struve, Gleb Review of ''Michael Bakunin'' pp. 726–728 from ''The Slavonic and East European Review'', Volume 16, Issue # 48, April 1938 *

The Vices of Integrity: E H Carr

E. H. Carr: historian of the future

by

E.H. Carr Studies in Revolutions

E. H. Carr and Isaac Deutscher: A Very Special Relationship

E.H. Carr The Historian As A Marxist Partisan

Review of The Vices of Integrity

by Alun Munslow

E.H. Carr vs. Idealism: The Battle Rages On

by

Papers of E. H. Carr

held at the

international relations

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such as ...

theorist, and an opponent of empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

within historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians ha ...

. Carr was best known for ''A History of Soviet Russia

''A History of Soviet Russia'' is a 14-volume work by E. H. Carr, covering the first twelve years of the history of the Soviet Union. It was first published from 1950 onward and re-issued from 1978 onward.

* ''The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917-1923'' ...

'', a 14-volume history of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

from 1917 to 1929, for his writings on international relations, particularly ''The Twenty Years' Crisis

''The Twenty Years' Crisis: 1919–1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations'' is a book on international relations written by E. H. Carr. The book was written in the 1930s shortly before the outbreak of World War&nbs ...

'', and for his book ''What Is History?

''What Is History?'' is a 1961 non-fiction book by historian E. H. Carr on historiography. It discusses history, facts, the bias of historians, science, morality, individuals and society, and moral judgements in history.

The book originated in a ...

'' in which he laid out historiographical principles rejecting traditional historical methods and practices.

Educated at the Merchant Taylors' School, London, and then at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

, Carr began his career as a diplomat in 1916; three years later, he participated at the Paris Peace Conference as a member of the British delegation. Becoming increasingly preoccupied with the study of international relations and of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, he resigned from the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

in 1936 to begin an academic career. From 1941 to 1946, Carr worked as an assistant editor at ''The Times'', where he was noted for his leaders (editorials) urging a socialist system and an Anglo-Soviet alliance as the basis of a post-war order.

Early life

Carr was born in London to a middle-class family, and was educated at the Merchant Taylors' School in London andTrinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

, where he was awarded a First Class Degree in Classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

in 1916.Hughes-Warrington, p. 24 Carr's family had originated in northern England, and the first mention of his ancestors was a George Carr who served as the Sheriff of Newcastle in 1450. Carr's parents were Francis Parker and Jesse (née Hallet) Carr.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 475 They were initially Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, but went over to supporting the Liberals in 1903 over the issue of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

. When Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

proclaimed his opposition to free trade and announced in favour of Imperial Preference

Imperial Preference was a system of mutual tariff reduction enacted throughout the British Empire following the Ottawa Conference of 1932. As Commonwealth Preference, the proposal was later revived in regard to the members of the Commonwealth of N ...

, Carr's father, to whom all tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s were abhorrent, switched his political loyalties.

Carr described the atmosphere at the Merchant Taylors School: "95% of my school fellows came from orthodox Conservative homes, and regarded Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

as an incarnation of the devil. We Liberals were a tiny despised minority."Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 476 From his parents, Carr inherited a strong belief in progress as an unstoppable force in world affairs, and throughout his life a recurring theme in Carr's thinking was that the world was progressively becoming a better place.Haslam, "We Need a Faith", p. 36 In 1911, Carr won the Craven Scholarship to attend Trinity College at Cambridge. At Cambridge, Carr was much impressed by hearing one of his professors lecture on how the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

influenced Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

in the writing of the ''Histories''.Haslam, "We Need a Faith", p. 39 Carr found this to be a great discovery—the subjectivity of the historian's craft. This discovery was later to influence his 1961 book ''What Is History?''

Diplomatic career

Like many of his generation, Carr found World War I to be a shattering experience as it destroyed the world he had known before 1914. He joined the BritishForeign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

in 1916, resigning in 1936. Carr was excused from military service for medical reasons. He was at first assigned to the Contraband Department of the Foreign Office, which sought to enforce the blockade on Germany, and then in 1917 was assigned to the Northern Department, which amongst other areas dealt with relations with Russia. As a diplomat, Carr was later praised by the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 19 ...

as someone who had "distinguished himself not only by sound learning and political understanding, but also in administrative ability".

At first, Carr knew nothing about the Bolsheviks. He later recalled of having some "vague impression of the revolutionary views of Lenin and Trotsky" but of knowing nothing of Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 477 By 1919, Carr had become convinced that the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s were destined to win the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, and approved of the Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

's opposition to the anti-Bolshevik ideas of the War Secretary Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

on the grounds of ''realpolitik

''Realpolitik'' (; ) refers to enacting or engaging in diplomatic or political policies based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than strictly binding itself to explicit ideological notions or moral and ethical ...

''. He later wrote that in the spring of 1919 he "was disappointed when he loyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

gave way (in part) on the Russian question in order to buy French consent to concessions to Germany". In 1919, Carr was part of the British delegation at the Paris Peace Conference and was involved in the drafting of parts of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

relating to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. During the conference, Carr was much offended at the Allied, especially French, treatment of the Germans, writing that the German delegation at the peace conference were "cheated over the 'Fourteen Points', and subjected to every petty humiliation". Beside working on the sections of the Versailles treaty relating to the League of Nations, Carr was also involved in working out the borders between Germany and Poland. Initially, Carr favoured Poland, urging in a memo in February 1919 that Britain recognise Poland at once, and that the German city of Danzig (modern Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

, Poland) be ceded to Poland. In March 1919, Carr fought against the idea of a Minorities Treaty for Poland, arguing that the rights of ethnic and religious minorities in Poland would be best guaranteed by not involving the international community in Polish internal affairs. By the spring of 1919, Carr's relations with the Polish delegation had declined to a state of mutual hostility.Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'', p. 29 Carr's tendency to favour the claims of the Germans at the expense of the Poles led Adam Zamoyski

Adam Zamoyski (born 11 January 1949) is a British historian and author.

Personal life

Born in New York City in 1949, Adam Stefan Zamoyski was brought up in England and educated at St Philip's Preparatory School, The Queen's College, Oxford, ...

to note that Carr "held views of the most extraordinary racial arrogance on all of the nations of Eastern Europe". Carr's biographer, Jonathan Haslam, wrote that Carr grew up in a place where German culture was deeply appreciated, which in turn always coloured his views towards Germany throughout his life. As a result, Carr supported the territorial claims of the ''Reich'' against Poland. In a letter written in 1954 to his friend Isaac Deutscher

Isaac; grc, Ἰσαάκ, Isaák; ar, إسحٰق/إسحاق, Isḥāq; am, ይስሐቅ is one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He was th ...

, Carr described his attitude to Poland at the time: "The picture of Poland that was universal in Eastern Europe right down to 1925 was of a strong and potentially predatory power."

After the peace conference, Carr was stationed at the British Embassy in Paris until 1921, and in 1920 was awarded a CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

. At first, Carr had great faith in the League, which he believed would prevent both another world war and ensure a better post-war world. In the 1920s, Carr was assigned to the branch of the British Foreign Office that dealt with the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

before being sent to the British Embassy in Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the Ba ...

, Latvia, where he served as Second Secretary between 1925 and 1929. In 1925, Carr married Anne Ward Howe, by whom he had one son.Cobb, Adam "Carr, E.H." pp. 180–181 from ''The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing'', Volume 1, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1999 p. 180 During his time in Riga (which at that time possessed a substantial Russian émigré community), Carr became increasingly fascinated with Russian literature and culture and wrote several works on various aspects of Russian life. Carr learnt Russian during his time in Riga, to read Russian writers in the original. In 1927, Carr paid his first visit to Moscow. He was later to write that reading Alexander Herzen

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Ге́рцен, translit=Alexándr Ivánovich Gértsen; ) was a Russian writer and thinker known as the "father of Russian socialism" and one of the main fathers of agra ...

, Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

and the work of other 19th-century Russian intellectuals caused him to re-think his liberal views. Starting in 1929, Carr began to review books relating to all things Russian and Soviet and to international relations in several British literary journals and, towards the end of his life, in the ''London Review of Books

The ''London Review of Books'' (''LRB'') is a British literary magazine published twice monthly that features articles and essays on fiction and non-fiction subjects, which are usually structured as book reviews.

History

The ''London Review of ...

''. In particular, Carr emerged as the ''Times Literary Supplements Soviet expert in the early 1930s, a position he still held at the time of his death in 1982. Because of his status as a diplomat (until 1936), most of Carr's reviews in the period 1929–36 were published either anonymously or under the pseudonym "John Hallett". In the summer of 1929, Carr began work on a biography of Fyodor Dostoyevsky and, in the course of researching Dostoevsky's life, Carr befriended Prince D. S. Mirsky

D. S. Mirsky is the English pen-name of Dmitry Petrovich Svyatopolk-Mirsky (russian: Дми́трий Петро́вич Святопо́лк-Ми́рский), often known as Prince Mirsky ( – c. 7 June 1939), a Russian political and lit ...

, a Russian émigré scholar living at that time in Britain. Beside studies on international relations

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such as ...

, Carr's writings in the 1930s included biographies of Dostoyevsky (1931), Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

(1934), and Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

(1937). An early sign of Carr's increasing admiration of the Soviet Union was a 1929 review of Baron Pyotr Wrangel

Baron Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel (russian: Пётр Никола́евич барон Вра́нгель, translit=Pëtr Nikoláevič Vrángel', p=ˈvranɡʲɪlʲ, german: Freiherr Peter Nikolaus von Wrangel; April 25, 1928), also known by his ni ...

's memoirs.

In an article entitled "Age of Reason" published in the ''Spectator'' on 26 April 1930, Carr attacked what he regarded as the prevailing culture of pessimism within the West, which he blamed on the French writer Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, critic, and essayist who wrote the monumental novel ''In Search of Lost Time'' (''À la recherche du temps perdu''; with the previous Eng ...

.Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'', p. 47 In the early 1930s, Carr found the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

to be almost as profoundly shocking as the First World War.Haslam, "We Need a Faith", p. 37 Further increasing Carr's interest in a replacement ideology for liberalism was his reaction to hearing the debates in January 1931 at the General Assembly of the League of Nations in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, Switzerland, and especially the speeches on the merits of free trade between the Yugoslav Foreign Minister Vojislav Marinkovich and the British Foreign Secretary Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of th ...

.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 481 It was at this time that Carr started to admire the Soviet Union. In a 1932 book review of Lancelot Lawton

Lancelot Francis Lawton (28 December 1880 – September 1947) was a British historian, military officer, scholar of Ukrainian studies, activist, and international political journalist who reported from Japan and the Soviet Union. He authore ...

's ''Economic History of Soviet Russia'', Carr dismissed Lawton's claim that the Soviet economy was a failure, and praised the British Marxist economist Maurice Dobb

Maurice Herbert Dobb (24 July 1900 – 17 August 1976) was an English economist at Cambridge University and a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. He is remembered as one of the pre-eminent Marxist economists of the 20th century.

Dobb was bo ...

's extremely favourable assessment of the Soviet economy. Davies, R.W. "Carr's Changing Views of the Soviet Union" pp. 91–108 from ''E.H. Carr: A Critical Appraisal'' ed. Michael Cox, London: Palgrave, 2000 p. 98

Carr's early political outlook was anti-Marxist and liberal. In his 1934 biography of Marx, Carr presented his subject as a highly intelligent man and a gifted writer, but one whose talents were devoted entirely to destruction.Laqueur, p. 113 Carr argued that Marx's sole and only motivation was a mindless class hatred. Carr labelled dialectical materialism

Dialectical materialism is a philosophy of science, history, and nature developed in Europe and based on the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxist dialectics, as a materialist philosophy, emphasizes the importance of real-world con ...

gibberish, and the labour theory of value doctrinal and derivative. He praised Marx for emphasising the importance of the collective over the individual. In view of his later conversion to a sort of quasi-Marxism, Carr was to find the passages in ''Karl Marx: A Study in Fanaticism'' criticising Marx to be highly embarrassing, and refused to allow the book to be republished. Carr was to later call it his worst book, and complained that he had written it only because his publisher had made a Marx biography a precondition for publishing the biography of Bakunin that he was writing. In his books such as ''The Romantic Exiles'' and ''Dostoevsky'', Carr was noted for his highly ironical treatment of his subjects, implying that their lives were of interest but not of great importance. In the mid-1930s, Carr was especially preoccupied with the life and ideas of Bakunin.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 479 During this period, Carr started writing a novel about the visit of a Bakunin-type Russian radical to Victorian Britain who proceeded to expose all of what Carr regarded as the pretensions and hypocrisies of British bourgeois society. The novel was never finished or published.

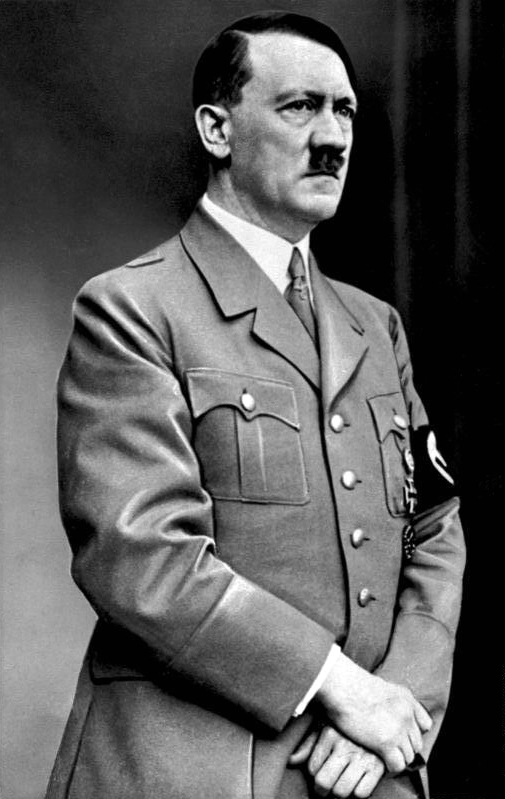

As a diplomat in the 1930s, Carr took the view that great division of the world into rival trading blocs caused by the American Smoot–Hawley Act of 1930 was the principal cause of German belligerence in foreign policy, as Germany was now unable to export finished goods or import raw materials cheaply. In Carr's opinion, if Germany could be given its own economic zone to dominate in Eastern Europecomparable to the British Imperial preference economic zone, the US dollar zone in the Americas, the French gold bloc zone, and the Japanese economic zonethen the peace of the world could be assured. In an essay published in February 1933 in the ''Fortnightly Review'', Carr blamed what he regarded as a punitive Versailles treaty for the recent accession to power of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

.Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'', p. 59 Carr's views on appeasement caused much tension with his superior, the Permanent Undersecretary Sir Robert Vansittart, and played a role in Carr's resignation from the Foreign Office later in 1936. In an article entitled "An English Nationalist Abroad" published in May 1936 in the ''Spectator'', Carr wrote: "The methods of the Tudor sovereigns, when they were making the English nation, invite many comparisons with those of the Nazi regime in Germany".Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'', p. 79 In this way, Carr argued that it was hypocritical for people in Britain to criticise the Nazi regime's human rights record. Because of Carr's strong antagonism to the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, which he viewed as unjust to Germany, Carr was very supportive of the Nazi regime's efforts to destroy Versailles through moves such as the remilitarisation of the Rhineland

The remilitarization of the Rhineland () began on 7 March 1936, when German military forces entered the Rhineland, which directly contravened the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Treaties. Neither France nor Britain was prepared for a milita ...

in 1936.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 483 Of his views in the 1930s, Carr later wrote: "No doubt, I was very blind."

International relations scholar

In 1936, Carr became the Woodrow Wilson Professor of International Politics at theUniversity College of Wales, Aberystwyth

, mottoeng = A world without knowledge is no world at all

, established = 1872 (as ''The University College of Wales'')

, former_names = University of Wales, Aberystwyth

, type = Public

, endowment = ...

, and is particularly known for his contribution on international relations theory

International relations theory is the study of international relations (IR) from a theoretical perspective. It seeks to explain causal and constitutive effects in international politics. Ole Holsti describes international relations theories as a ...

. Carr's last words of advice as a diplomat were a memo urging that Britain accept the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

as an exclusive zone of influence for Germany. Additionally, in articles published in ''The Christian Science Monitor

''The Christian Science Monitor'' (''CSM''), commonly known as ''The Monitor'', is a nonprofit news organization that publishes daily articles in electronic format as well as a weekly print edition. It was founded in 1908 as a daily newspaper ...

'' on 2 December 1936 and in the January 1937 edition of ''Fortnightly Review

''The Fortnightly Review'' was one of the most prominent and influential magazines in nineteenth-century England. It was founded in 1865 by Anthony Trollope, Frederic Harrison, Edward Spencer Beesly, and six others with an investment of £9,000; ...

'', Carr argued that the Soviet Union and France were not working for collective security

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, political, regional, or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats t ...

but rather "a division of the Great Powers into two armored camps", supported non-intervention in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

, and asserted that King Leopold III of Belgium

Leopold III (3 November 1901 – 25 September 1983) was King of the Belgians from 23 February 1934 until his abdication on 16 July 1951. At the outbreak of World War II, Leopold tried to maintain Belgian neutrality, but after the German invasi ...

had made a major step towards peace with his declaration of neutrality of 14 October 1936.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 484 Two major intellectual influences on Carr in the mid-1930s were Karl Mannheim

Karl Mannheim (born Károly Manheim, 27 March 1893 – 9 January 1947) was an influential Hungarian sociologist during the first half of the 20th century. He is a key figure in classical sociology, as well as one of the founders of the sociolo ...

's 1936 book ''Ideology and Utopia'', and the work of Reinhold Niebuhr

Karl Paul Reinhold Niebuhr (June 21, 1892 – June 1, 1971) was an American Reformed theologian, ethicist, commentator on politics and public affairs, and professor at Union Theological Seminary for more than 30 years. Niebuhr was one of America ...

on the need to combine morality with realism.

Carr's appointment as the Woodrow Wilson Professor of International Politics caused a stir when he started to use his position to criticise the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, a viewpoint which caused much tension with his benefactor, Lord Davies, who was a strong supporter of the League.Porter, pp. 50–51 Lord Davies had established the Wilson Chair in 1924 with the intention of increasing public support for his beloved League, which helps to explain his chagrin at Carr's anti-League lectures. In his first lecture on 14 October 1936 Carr stated that the League was ineffective.Porter, p. 51

In 1936, Carr began to work for Chatham House

Chatham House, also known as the Royal Institute of International Affairs, is an independent policy institute headquartered in London. Its stated mission is to provide commentary on world events and offer solutions to global challenges. It is ...

, where he chaired a study group tasked with producing a report on nationalism. The report was published in 1939.

In 1937, Carr visited the Soviet Union for a second time, and was impressed by what he saw. During his visit, Carr may have inadvertently caused the death of his friend, Prince

In 1937, Carr visited the Soviet Union for a second time, and was impressed by what he saw. During his visit, Carr may have inadvertently caused the death of his friend, Prince D. S. Mirsky

D. S. Mirsky is the English pen-name of Dmitry Petrovich Svyatopolk-Mirsky (russian: Дми́трий Петро́вич Святопо́лк-Ми́рский), often known as Prince Mirsky ( – c. 7 June 1939), a Russian political and lit ...

.Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'', p. 76 Carr stumbled into Prince Mirsky on the streets of Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(modern Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

), and despite Prince Mirsky's best efforts to pretend not to know him, Carr persuaded his old friend to have lunch with him. Since this was at the height of the ''Yezhovshchina'', and any Soviet citizen who had any unauthorised contact with a foreigner was likely to be regarded as a spy, the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

arrested Prince Mirsky as a British spy; he died two years later in a Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

camp near Magadan

Magadan ( rus, Магадан, p=məɡɐˈdan) is a port town and the administrative center of Magadan Oblast, Russia, located on the Sea of Okhotsk in Nagayev Bay (within Taui Bay) and serving as a gateway to the Kolyma region.

History

Maga ...

. As part of the same trip that took Carr to the Soviet Union in 1937 was a visit to Germany. In a speech given on 12 October 1937 at Chatham House summarising his impressions of those two countries, Carr reported that Germany was "almost a free country".Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'', p. 78 Apparently unaware of the fate of Prince Mirsky, Carr spoke of the "strange behaviour" of his old friend, who had at first gone to great lengths to try to pretend that he did not know Carr during their accidental meeting.

In the 1930s, Carr was a leading supporter of appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governm ...

.Laqueur, pp. 113–114 In his writings on international affairs in British newspapers, Carr criticised the Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1945 to 1948. He also led the Czechoslovak government-in-exile 1939 to 1945 ...

for clinging to the alliance with France, rather than accepting that it was his country's destiny to be in the German sphere of influence. At the same time, Carr strongly praised the Polish Foreign Minister Colonel Józef Beck

Józef Beck (; 4 October 1894 – 5 June 1944) was a Poles, Polish statesman who served the Second Republic of Poland as a diplomat and military officer. A close associate of Józef Piłsudski, Beck is most famous for being Polish foreign minist ...

for his balancing act between France, Germany, and the Soviet Union. In the late 1930s, Carr started to become even more sympathetic toward the Soviet Union, as he was much impressed by the achievements of the Five-Year Plans Five-year plan may refer to:

Nation plans

*Five-year plans of the Soviet Union, a series of nationwide centralized economic plans in the Soviet Union

*Five-Year Plans of Argentina

*Five-Year Plans of Bhutan, a series of national economic developm ...

, which stood in marked contrast to the failures of capitalism during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

.

His famous work ''The Twenty Years' Crisis

''The Twenty Years' Crisis: 1919–1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations'' is a book on international relations written by E. H. Carr. The book was written in the 1930s shortly before the outbreak of World War&nbs ...

'' was published in July 1939, which dealt with the subject of international relations between 1919 and 1939. In that book, Carr defended appeasement on the ground that it was the only realistic policy option.Laqueur, p. 114 At the time the book was published in the summer of 1939, Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

had adopted his "containment" policy towards Germany, leading Carr to later ruefully comment that his book was dated even before it was published. In the spring and summer of 1939, Carr was very dubious about Chamberlain's "guarantee" of Polish independence issued on 31 March 1939.

In ''The Twenty Year's Crisis'', Carr divided thinkers on international relations into two schools, which he labelled the utopians and the realists. Reflecting his own disillusion with the League of Nations, Carr attacked as "utopians" those like

In ''The Twenty Year's Crisis'', Carr divided thinkers on international relations into two schools, which he labelled the utopians and the realists. Reflecting his own disillusion with the League of Nations, Carr attacked as "utopians" those like Norman Angell

Sir Ralph Norman Angell (26 December 1872 – 7 October 1967) was an English Nobel Peace Prize winner. He was a lecturer, journalist, author and Member of Parliament for the Labour Party.

Angell was one of the principal founders of the Union o ...

who believed that a new and better international structure could be built around the League. In Carr's opinion, the entire international order constructed at Versailles was flawed and the League was a hopeless dream that could never do anything practical. Carr described the opposition of utopianism and realism in international relations as a dialectic progress.Laqueur, p. 115 He argued that in realism there is no moral dimension, so that for a realist what is successful is right and what is unsuccessful is wrong.

Carr contended that international relations was an incessant struggle between the economically privileged "have" powers and the economically disadvantaged "have not" powers. In this economic understanding of international relations, "have" powers like the United States, Britain and France were inclined to avoid war because of their contented status whereas "have not" powers like Germany, Italy and Japan were inclined towards war as they had nothing to lose.Jones, Charles ''E.H. Carr and International Relations: A Duty to Lie'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998 p. 29 Carr defended the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

as the overdue recognition of changes in the balance of power. In ''The Twenty Years' Crisis'', he was highly critical of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, whom Carr described as a mere opportunist interested only in power for himself.

Carr immediately followed up ''The Twenty Year's Crisis'' with ''Britain: A Study of Foreign Policy From The Versailles Treaty to the Outbreak of War'', a study of British foreign policy in the inter-war period that featured a preface by the Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 19 ...

. Carr ended his support for appeasement, which he had so vociferously expressed in ''The Twenty Year's Crisis'', with a favourable review of a book containing a collection of Churchill's speeches from 1936 to 1938, which Carr wrote were "justifiably" alarmist about Germany. After 1939, Carr largely abandoned writing about international relations in favour of contemporary events and Soviet history

The history of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union (USSR) reflects a period of change for both Russia and the world. Though the terms "Soviet Russia" and "Soviet Union" often are synonymous in everyday speech (either acknowledging the dominance ...

. Carr was to write only three more books about international relations after 1939, namely ''The Future of Nations; Independence Or Interdependence?'' (1941), ''German-Soviet Relations Between the Two World Wars, 1919–1939'' (1951) and ''International Relations Between the Two World Wars, 1919–1939'' (1955). After the outbreak of World War II, Carr stated that he had been somewhat mistaken in his prewar views on Nazi Germany. In the 1946 revised edition of ''The Twenty Years' Crisis'', Carr was more hostile in his appraisal of German foreign policy than he had been in the first edition in 1939.

Some of the major themes of Carr's writings were change and the relationship between ideational and material forces in society. He saw as a major theme of history the growth of reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

as a social force. He argued that all major social changes had been caused by revolutions or wars, both of which Carr regarded as necessary but unpleasant means of accomplishing social change.

World War II

During World War II, Carr's political views took a sharp turn towards the left. He spent thePhoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germ ...

working as a clerk with the propaganda department of the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

. As Carr did not believe that Britain could defeat Germany, the declaration of war on Germany on 3 September 1939 left him highly depressed.

In March 1940, Carr resigned from the Foreign Office to serve as the writer of leaders (editorials) for ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

''.Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'', p. 84 In his second leader, published on 21 June 1940 and entitled "The German Dream", Carr wrote that Hitler was offering a "Europe united by conquest". In a leader during the summer of 1940, Carr supported the Soviet annexation of the Baltic States

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

.

Carr served as the assistant editor of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' from 1941 to 1946, during which time he was well known for the pro-Soviet attitudes that he expressed in his leaders. After June 1941, Carr' s already strong admiration for the Soviet Union was much increased by the Soviet Union's role in defeating Germany.

In a leader of 5 December 1940 entitled "The Two Scourges", Carr wrote that only by removing the "scourge" of unemployment could one also remove the "scourge" of war.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 487 Such was the popularity of "The Two Scourges" that it was published as a pamphlet in December 1940, during which its first print run of 10,000 completely sold out. Carr's left-wing leaders caused some tension with the editor of the ''Times'', Geoffrey Dawson

George Geoffrey Dawson (25 October 1874 – 7 November 1944) was editor of ''The Times'' from 1912 to 1919 and again from 1923 until 1941. His original last name was Robinson, but he changed it in 1917. He married Hon. Margaret Cecilia Lawley, ...

, who felt that Carr was taking the ''Times'' in too radical a direction, which led to Carr being restricted for a time to writing only on foreign policy. After Dawson was ousted in May 1941 and replacemed with Robert M'Gowan Barrington-Ward, Carr was given a free rein to write on whatever he wished. In turn, Barrington-Ward was to find many of Carr's leaders on foreign affairs to be too radical for his liking.

Carr's leaders were noted for their advocacy of a socialist European economy under the control of an international planning board, and for his support for the idea of an Anglo-Soviet alliance as the basis of the post-war international order. Unlike many of his contemporaries in war-time Britain, Carr was against a Carthaginian peace

A Carthaginian peace is the imposition of a very brutal "peace" intended to permanently cripple the losing side. The term derives from the peace terms imposed on the Carthaginian Empire by the Roman Republic following the Punic Wars. After the Seco ...

with Germany, and argued for a post-war reconstruction of Germany along socialist lines.Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'', p. 100 In his leaders on foreign affairs, Carr was very consistent in arguing after 1941 that, once the war ended, it was the fate of Eastern Europe to come into the Soviet sphere of influence, and claimed that any effort to the contrary was both vain and immoral.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 488

Between 1942 and 1945, Carr was the Chairman of a study group at the Royal Institute of International Affairs

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

concerned with Anglo-Soviet relations. Carr's study group concluded that Stalin had largely abandoned Communist ideology in favour of Russian nationalism, that the Soviet economy would provide a higher standard of living in the Soviet Union after the war, and that it was both possible and desirable for Britain to reach a friendly understanding with the Soviets once the war had ended. In 1942, Carr published '' Conditions of Peace'', followed by '' Nationalism and After'' in 1945, in which he outlined his ideas about how the post-war world should look. In his books, and his ''Times'' leaders, Carr urged for the creation of a socialist European federation anchored by an Anglo-German partnership that would be aligned with the Soviet Union against the United States.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 489

In his 1942 book ''Conditions of Peace'', Carr argued that it was a flawed economic system that had caused World War II and that the only way of preventing another world war was for the Western powers to adopt socialism. One of the main sources for ideas in ''Conditions of Peace'' was the 1940 book ''Dynamics of War and Revolution'' by the American Lawrence Dennis

Lawrence Dennis (December 25, 1893 – August 20, 1977) was a mixed-race American diplomat, consultant and author. He advocated fascism in America after the Great Depression, arguing that liberal capitalism was doomed and one-party planning of ...

. In a review of ''Conditions of Peace'', the British writer Rebecca West

Dame Cicily Isabel Fairfield (21 December 1892 – 15 March 1983), known as Rebecca West, or Dame Rebecca West, was a British author, journalist, literary critic and travel writer. An author who wrote in many genres, West reviewed books ...

criticised Carr for using Dennis as a source, commenting: "It is as odd for a serious English writer to quote Sir Oswald Mosley". In a speech on 2 June 1942 in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, Viscount Elibank

Lord Elibank, of Ettrick Forest in the County of Selkirk, is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1643 for Sir Patrick Murray, 1st Baronet, with remainder to his heirs male whatsoever. He had already been created a Baronet, of E ...

attacked Carr as an "active danger" for his views in ''Conditions of Peace'' about a magnanimous peace with Germany and for suggesting that Britain turn over all of her colonies to an international commission after the war.

The next month, Carr's relations with the Polish government were further worsened by the storm caused by the discovery of the Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, "Katyń crime"; russian: link=yes, Катынская резня ''Katynskaya reznya'', "Katyn massacre", or russian: link=no, Катынский расстрел, ''Katynsky rasstrel'', "Katyn execution" was a series of m ...

committed by the Russian NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

in 1940. In a leader entitled "Russia and Poland" on 28 April 1943, Carr blasted the Polish government for accusing the Soviets of committing the Katyn massacre and for asking the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

to investigate.Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'', p. 104

Lord Davies, who had been extremely unhappy with Carr almost from the moment that Carr had assumed the Wilson Chair in 1936, launched a major campaign in 1943 to have Carr fired, being particularly upset that, although Carr had not taught since 1939, he was still drawing his professor's salary. Lord Davies's efforts to have Carr fired failed when a majority of the Aberystwyth staff, supported by the powerful Welsh political fixer Thomas Jones, sided with Carr.

In December 1944, when fighting broke out in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

between the Greek Communist front organisation ELAS

The Greek People's Liberation Army ( el, Ελληνικός Λαϊκός Απελευθερωτικός Στρατός (ΕΛΑΣ), ''Ellinikós Laïkós Apeleftherotikós Stratós'' (ELAS) was the military arm of the left-wing National Liberat ...

and the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, Carr in a ''Times'' leader sided with the Greek Communists, leading to Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

to condemn him in a speech to the House of Commons. Carr claimed that the Greek EAM was the "largest organised party or group of parties in Greece", which "appeared to exercise almost unchallengeable authority", and called for Britain to recognise the EAM as the legal Greek government.Conquest, Robert "Agit-Prof" pp. 32–38 from ''The New Republic'', Volume 424, Issue # 4, 1 November 1999 p. 33

In contrast to his support for EAM/ELAS, Carr was strongly critical of the legitimate Polish government in exile and its Armia Krajowa

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) esta ...

(Home Army) resistance organisation. In his leaders of 1944 on Poland, Carr urged that Britain break diplomatic relations with the London government and recognise the Soviet-sponsored Lublin government

The Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polish: ''Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego'', ''PKWN''), also known as the Lublin Committee, was an executive governing authority established by the Soviet-backed communists in Poland at the lat ...

as the lawful government of Poland.

In a May 1945 leader, Carr blasted those who felt that an Anglo-American "special relationship' would be the principal bulwark of peace. As a result of Carr's leaders, the ''Times'' became popularly known during World War II as the three-pence ''Daily Worker'' (the price of the ''Daily Worker'' being one penny). Commenting on Carr's pro-Soviet leaders, the British writer George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

wrote in 1942 that "all the appeasers, e.g. Professor E. H. Carr, have switched their allegiance from Hitler to Stalin".

Reflecting his disgust with Carr's leaders in the ''Times'', the British civil servant Sir Alexander Cadogan

Sir Alexander Montagu George Cadogan (25 November 1884 – 9 July 1968) was a British diplomat and civil servant. He was Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs from 1938 to 1946. His long tenure of the Permanent Secretary's office makes ...

, the Permanent Undersecretary at the Foreign Office, wrote in his diary: "I hope someone will tie Barrington-Ward and Ted Carr together and throw them into the Thames."

During a 1945 lecture series entitled ''The Soviet Impact on the Western World'', which was published as a book in 1946, Carr argued that "The trend away from individualism and towards totalitarianism is everywhere unmistakable", that Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

was the by far the most successful type of totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

as proved by Soviet industrial growth and the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

's role in defeating Germany, and that only the "blind and incurable ignored these trends".Laqueur, p. 131 During the same lectures, Carr called democracy in the Western world a sham, which permitted a capitalist ruling class to exploit the majority, and praised the Soviet Union as offering real democracy. One of Carr's leading associates, the British historian R. W. Davies

Robert William Davies (23 April 1925 – 13 April 2021), better known as R. W. Davies or Bob Davies, was a British historian, writer and professor of Soviet Economic Studies at the University of Birmingham.

Obtaining his PhD in 1954, Davies w ...

, was later to write that Carr's view of the Soviet Union as expressed in ''The Soviet Impact on the Western World'' was a rather glossy and idealised picture.

Cold War

In 1946, Carr started living with Joyce Marion Stock Forde, who was to remain his common law wife until 1964. In 1947, Carr was forced to resign from his position at Aberystwyth.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 491 In the late 1940s, Carr started to become increasingly influenced byMarxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

. His name was on Orwell's list

In 1949, shortly before he died, the English author George Orwell prepared a list of notable writers and other people he considered to be unsuitable as possible writers for the anti-communist propaganda activities of the Information Research D ...

, a list of people which George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

prepared in March 1949 for the Information Research Department

The Information Research Department (IRD) was a secret Cold War propaganda department of the British Foreign Office, created to publish anti-communist propaganda, including black propaganda, provide support and information to anti-communist pol ...

, a propaganda unit set up at the Foreign Office by the Labour government. Orwell considered these people to have pro-communist leanings and therefore to be inappropriate to write for the IRD. In 1948, Carr condemned the British acceptance of an American loan in 1946 as marking the effective end of British independence.Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'' p. 152 Carr went on to write that the best course for Britain was to seek neutrality in the Cold War and that "peace at any price must be the foundation of British policy".Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'' p. 153 Carr took a great deal of hope from the Soviet–Yugoslav split of 1948.Haslam''The Vices of Integrity''

p. 151 In May–June 1951, Carr delivered a series of speeches on British radio entitled ''The New Society'', that advocated a commitment to mass democracy, egalitarian democracy, and "public control and planning" of the economy. Carr was a reclusive man whom few knew well, but his circle of close friends included

Isaac Deutscher

Isaac; grc, Ἰσαάκ, Isaák; ar, إسحٰق/إسحاق, Isḥāq; am, ይስሐቅ is one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He was th ...

, A. J. P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his televis ...

, Harold Laski

Harold Joseph Laski (30 June 1893 – 24 March 1950) was an English political theorist and economist. He was active in politics and served as the chairman of the British Labour Party from 1945 to 1946 and was a professor at the London School of ...

and Karl Mannheim

Karl Mannheim (born Károly Manheim, 27 March 1893 – 9 January 1947) was an influential Hungarian sociologist during the first half of the 20th century. He is a key figure in classical sociology, as well as one of the founders of the sociolo ...

. Carr was especially close to Deutscher. In the early 1950s, when Carr sat on the editorial board of Chatham House

Chatham House, also known as the Royal Institute of International Affairs, is an independent policy institute headquartered in London. Its stated mission is to provide commentary on world events and offer solutions to global challenges. It is ...

, he attempted to block the publication of the manuscript that eventually became ''The Origins of the Communist Autocracy'' by Leonard Schapiro

Leonard Bertram Naman Schapiro (22 April 1908 in Glasgow – 2 November 1983 in London) was the leading British scholar of the origins and development of the Soviet political system. He taught for many years at the London School of Economics ...

on the ground that the subject of repression in the Soviet Union {{Unreferenced, date=June 2019, bot=noref (GreenC bot)

There were many forms of repression in the Soviet Union carried out by the Soviet government and the ruling Communist Party.

*Political repression in the Soviet Union

*Ideological repression ...

was not a serious topic for a historian.Haslam, ''The Vices of Integrity'' pp. 158–164 As interest in the subject of Communism grew, Carr largely abandoned international relations

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such as ...

as a field of study. In 1956, Carr did not comment on the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Uprising, while at the same time condemning the Suez War

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

.

In 1966, Carr left Forde and married the historian Betty Behrens

Catherine Betty Abigail Behrens (24 April 1904 – 3 January 1989), known as Betty Behrens and published as C. B. A. Behrens, was a British historian and academic. Her early interests included Henry VIII, Charles II, and the early modern period ...

. That same year, Carr wrote in an essay that in India, where "liberalism is professed and to some extent practised, millions of people would die without American charity. In China, where liberalism is rejected, people somehow get fed. Which is the more cruel and oppressive regime?"Conquest, Robert "Agit-Prof" pp. 32–38 from ''The New Republic'', Volume 424, Issue # 4, 1 November 1999 p. 36 One of Carr's critics, the British historian Robert Conquest

George Robert Acworth Conquest (15 July 1917 – 3 August 2015) was a British historian and poet.

A long-time research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, Conquest was most notable for his work on the Soviet Union. His books ...

, commented that Carr did not appear to be familiar with recent Chinese history, because, judging from that remark, Carr seemed to be ignorant of the millions of Chinese who had starved to death during the Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward (Second Five Year Plan) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an economic and social campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1958 to 1962. CCP Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to reconstruc ...

. In 1961, Carr published an anonymous and very favourable review of his friend A. J. P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his televis ...

's contentious book ''The Origins of the Second World War

''The Origins of the Second World War'' is a non-fiction book by the English historian A. J. P. Taylor, examining the causes of World War II. It was first published in 1961 by Hamish Hamilton.

Origins

Taylor had previously written ''The Struggle ...

'', which caused much controversy. In the late 1960s, Carr was one of the few British professors to be supportive of the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights, g ...

student protestors, whom, he hoped, might bring about a socialist revolution in Britain.Haslam, "We Need a Faith", pp. 36–39 from ''History Today

''History Today'' is an illustrated history magazine. Published monthly in London since January 1951, it presents serious and authoritative history to as wide a public as possible. The magazine covers all periods and geographical regions and pub ...

'', Volume 33, August 1983 p. 39 Car was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1967. In 1970, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

.

Carr exercised wide influence in the field of Soviet studies and international relations. The extent of Carr's influence could be seen in the 1974 ''festschrift

In academia, a ''Festschrift'' (; plural, ''Festschriften'' ) is a book honoring a respected person, especially an academic, and presented during their lifetime. It generally takes the form of an edited volume, containing contributions from the h ...

'' in his honour, entitled ''Essays in Honour of E.H. Carr'' ed. Chimen Abramsky

Chimen Abramsky ( he, שמעון אברמסקי; 12 September 1916 – 14 March 2010) was emeritus professor of Jewish studies at University College London. His first name is pronounced ''Shimon''.

Biography

Abramsky was born in Minsk to a Li ...

and Beryl Williams. The contributors included Sir Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

, Arthur Lehning

Paul Arthur Müller-Lehning (23 October 1899, in Utrecht – 1 January 2000, in Lys-Saint-Georges) was a Dutch author, historian and anarchist.

Arthur Lehning wrote noted French translations of Mikhail Bakunin. In 1992 he won the Gouden Ganzenve ...

, G. A. Cohen

Gerald Allan Cohen, ( ; 14 April 1941 – 5 August 2009) was a Canadian political philosopher who held the positions of Quain Professor of Jurisprudence, University College London and Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory, All Sou ...

, Monica Partridge

Prof. Monica Partridge born Monica Agnes McMain (25 May 1915 – 2008) was a British linguist and Russian and Serbo-Croatian scholar who was a benefactor to the University of Nottingham. She was the first woman to be a Professor at her university ...

, Beryl Williams, Eleonore Breuning, D. C. Watt, Mary Holdsworth, Roger Morgan, Alec Nove

Alexander Nove, FRSE, FBA (born Aleksandr Yakovlevich Novakovsky; russian: Алекса́ндр Я́ковлевич Новако́вский; also published under Alec Nove; 24 November 1915 – 15 May 1994) was a Professor of Economics at the ...

, John Erickson John Erickson may refer to:

* John E. Erickson (Montana politician) (1863–1946), American politician from Montana

* John E. Erickson (basketball) (1927–2020), American basketball coach and executive, Wisconsin politician

* John P. Erickson (1 ...

, Michael Kaser

Michael Kaser (2 May 1926 – 15 November 2021) was a British economist who specialised on Central and Eastern Europe and the USSR and its successor states. He was Reader Emeritus in Economics at the University of Oxford and Emeritus Fellow of ...

, R. W. Davies

Robert William Davies (23 April 1925 – 13 April 2021), better known as R. W. Davies or Bob Davies, was a British historian, writer and professor of Soviet Economic Studies at the University of Birmingham.

Obtaining his PhD in 1954, Davies w ...

, Moshe Lewin

Moshe "Misha" Lewin ( ; 7 November 1921 – 14 August 2010) was a scholar of Russian and Soviet history. He was a major figure in the school of Soviet studies which emerged in the 1960s.

Biography

Moshe Lewin was born in 1921 in Wilno, Poland (no ...

, Maurice Dobb

Maurice Herbert Dobb (24 July 1900 – 17 August 1976) was an English economist at Cambridge University and a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. He is remembered as one of the pre-eminent Marxist economists of the 20th century.

Dobb was bo ...

, and Lionel Kochan.Ambramsky, C. & Williams, Beryl ''Essays in Honour of E.H. Carr'' pp. v–vi

In a 1978 interview in ''New Left Review

The ''New Left Review'' is a British bimonthly journal covering world politics, economy, and culture, which was established in 1960.

History Background

As part of the British "New Left" a number of new journals emerged to carry commentary on m ...

'', Carr called Western economies "crazy" and doomed in the long run.Davies, "Edward Hallett Carr", p. 508 In a 1980 letter to his friend Tamara Deutscher

Tamara Deutscher (1 February 1913 – 7 August 1990) was a Polish-British writer and editor who researched the leaders of Soviet Communism, together with her husband Isaac Deutscher.

She was born Tamara Lebenhaft in Łódź, in what was then Congr ...

, Carr wrote that he felt that the government of Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

had forced "the forces of Socialism" in Britain into a "full retreat". In the same letter to Deutscher, Carr wrote that "Socialism cannot be obtained through reformism, i.e. through the machinery of bourgeois democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into di ...

". Carr went on to decry disunity on the left. Although Carr regarded the abandonment of Maoism

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Chi ...

in China in the late 1970s as a regressive development, he saw opportunities and wrote to his stockbroker in 1978 that "a lot of people, as well as the Japanese, are going to benefit from the opening up of trade with China. Have you any ideas?"

Controversy surrounds the question of whether Carr was an anti-Semite.Haslam, "E.H. Carr's Search for Meaning" pp. 21–35 from ''E.H. Carr A Critical Appraisal'' ed. Michael Cox, Palgrave: London, 2000 p. 27 Carr's critics point to his being champion of two anti-Semitic dictators (Hitler and Stalin) in succession, his opposition to Israel and to most of Carr's opponents, such as Sir Geoffrey Elton

Sir Geoffrey Rudolph Elton (born Gottfried Rudolf Otto Ehrenberg; 17 August 1921 – 4 December 1994) was a German-born British political and constitutional historian, specialising in the Tudor period. He taught at Clare College, Cambridge, and w ...

, Leonard Schapiro

Leonard Bertram Naman Schapiro (22 April 1908 in Glasgow – 2 November 1983 in London) was the leading British scholar of the origins and development of the Soviet political system. He taught for many years at the London School of Economics ...

, Sir Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the cl ...

, Bertram Wolfe

Bertram David Wolfe (January 19, 1896 – February 21, 1977) was an American scholar, leading communist, and later a leading anti-communist. He authored many works related to communism, including biographical studies of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Sta ...

, Richard Pipes

Richard Edgar Pipes ( yi, ריכארד פּיִפּעץ ''Rikhard Pipets'', the surname literally means 'beak'; pl, Ryszard Pipes; July 11, 1923 – May 17, 2018) was an American academic who specialized in Russian and Soviet history. He publish ...

, Adam Ulam

Adam Bruno Ulam (8 April 1922 – 28 March 2000) was a Polish-American historian of Jewish descent and political scientist at Harvard University. Ulam was one of the world's foremost authorities and top experts in Sovietology and Kremlinology ...

, Leopold Labedz, Sir Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

, and Walter Laqueur

Walter Ze'ev Laqueur (26 May 1921 – 30 September 2018) was a German-born American historian, journalist and political commentator. He was an influential scholar on the subjects of terrorism and political violence.

Biography

Walter Laqueur was ...

, being Jewish. Carr's defenders, such as Jonathan Haslam, have argued against the charge of anti-Semitism, noting that Carr had many Jewish friends (including such erstwhile intellectual sparring partners as Berlin and Namier), that his last wife Betty Behrens was Jewish and that his support for Nazi Germany in the 1930s and the Soviet Union in the 1940s–1950s was in spite of rather than because of anti-Semitism in those states.

''History of Soviet Russia''

After the war, Carr was a fellow and tutor in politics at

After the war, Carr was a fellow and tutor in politics at Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the f ...

, from 1953 to 1955, when he became a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

, where he remained until his death in 1982. During this period he published most of ''A History of Soviet Russia

''A History of Soviet Russia'' is a 14-volume work by E. H. Carr, covering the first twelve years of the history of the Soviet Union. It was first published from 1950 onward and re-issued from 1978 onward.

* ''The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917-1923'' ...