Edward A. Burke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Austin Burke or Burk (September 13, 1839 – September 24, 1928), was the Democratic State Treasurer of Louisiana following

Burke, by his own account, was of

Burke, by his own account, was of

In his newly adopted city Burke developed a friendship with

In his newly adopted city Burke developed a friendship with

In 1882, the National Cotton Planters Association proposed the idea of a "

In 1882, the National Cotton Planters Association proposed the idea of a "

Burke's financial fortunes did not appear to fare well in Honduras. Burke had to contend with a number of financial panics in both

Burke's financial fortunes did not appear to fare well in Honduras. Burke had to contend with a number of financial panics in both

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. Burke later fled to Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

after it was discovered that there were misappropriations of state treasury funds. While in Honduras Burke became a major land owner and held government positions within Honduras' nationalized railway systems. He remained an exile until his death nearly four decades later.

Early life and career

Burke, by his own account, was of

Burke, by his own account, was of Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

descent and born in Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

. He used the name "Burk" until after the Civil War. Burk's initial career started with the railroads. At the age of thirteen he was employed as a railroad telegraph operator in Urbana __NOTOC__

Urbana can refer to:

Places Italy

*Urbana, Italy

United States

*Urbana, Illinois

**Urbana (conference), a Christian conference formerly held in Urbana, Illinois

*Urbana, Indiana

* Urbana, Iowa

*Urbana, Kansas

* Urbana, Maryland

*Urbana, ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

. By the age of seventeen, he had been promoted to a division superintendent. The outbreak of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

found Burke working for a railroad in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

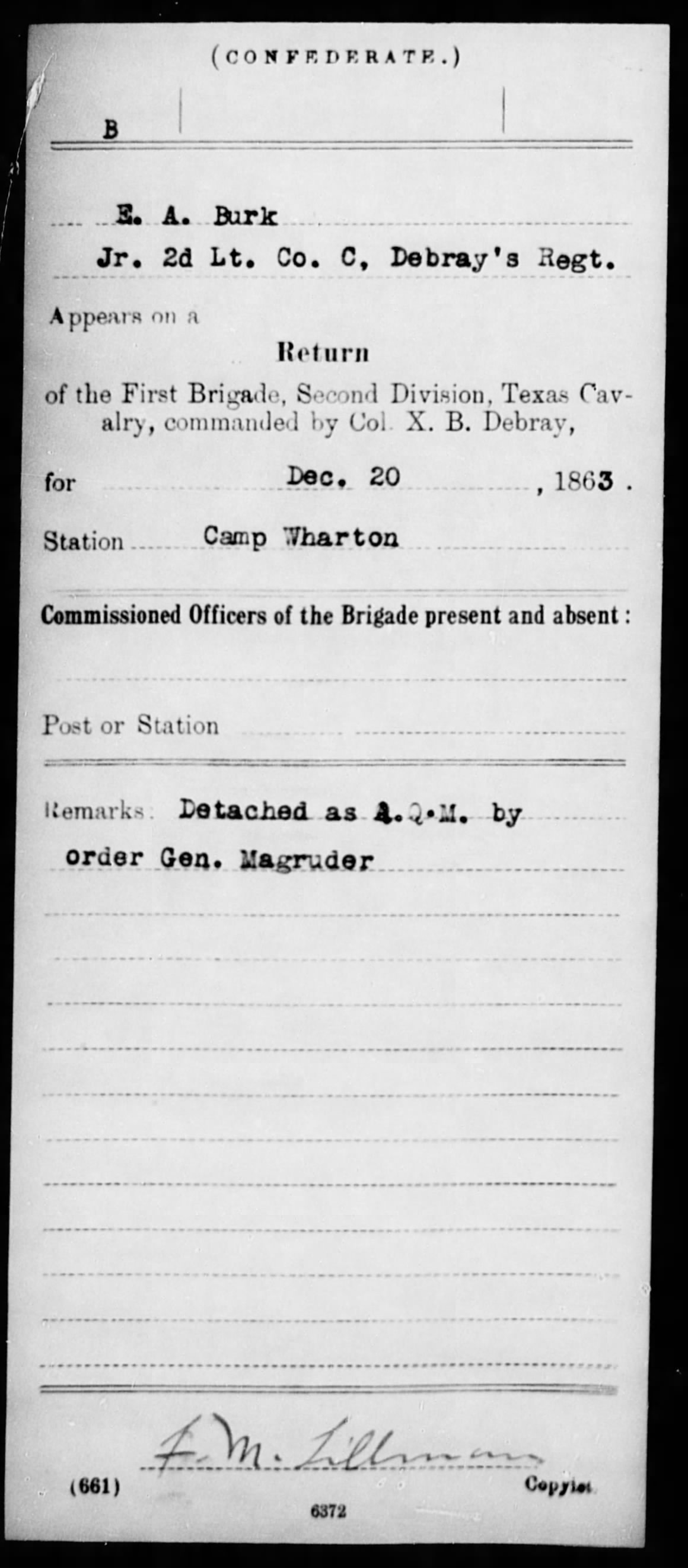

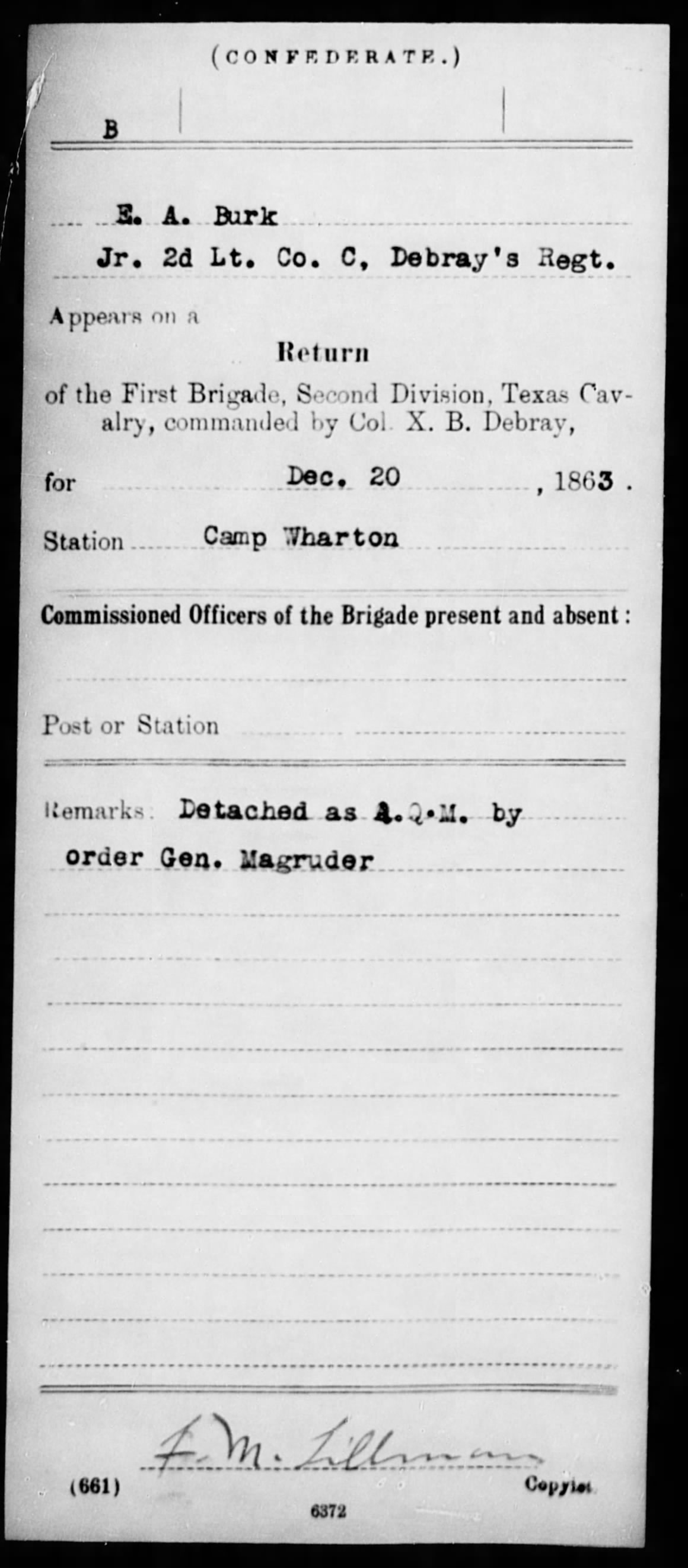

. On October 7, 1861 he was commissioned as a Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

officer into Debray's Mounted Battalion. His knowledge of transportation logistics gained through his years of railroad experience resulted in his temporary transfer to Texas' Office of Field Transportation in March 1863. By December of that year the transfer was permanent. Major E.A. Burk commanded the Houston Battalion, Texas Infantry of 145 men. By war's end Burke had reached the rank of major with a duty assignment as Quartermaster and Chief Inspector of Field Transportation, District of Texas. After the war Burke's business career wavered. In Galveston

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

he initially found work as telegraph operator and then as a manager of a cotton factorage. He later teamed up with another former Confederate officer, H. B. Stoddart, and formed the import export firm, Stoddart & Burk. The firm primarily exported cotton and imported liquor. In January 1869, the firm faced tax evasion

Tax evasion is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to reduce the taxp ...

charges from failure to pay federal taxes due on the imported alcohol. The charges against Burke were eventually dismissed, but the litigation left the firm and Burke in bankruptcy. Burke tried to revitalize his fortunes by being elected the Chief Engineer of Galveston's volunteer fire department.

New Orleans

Burke next appears inNew Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

in May 1869. At this point Burke added an "e" to his last name; prior to his arrival in New Orleans, Burke signed his name without an "e". Burke may have been trying to establish a new life in New Orleans and the minor name change may have helped him avoid Galveston creditors and distance himself from the alcohol tax scandal. Throughout his life, Burke also quoted different years of birth. Burke arrived in New Orleans during a commercial convention. He informed local New Orleanians, that he was in town to attend the convention and he was from the engineering firm of Stoddart & Burke. Burke, at first, found odd jobs in New Orleans, but eventually landed a position as a freight agent with the New Orleans, Jackson & Great Northern Railroad. In December 1869, Burke cut all his ties with Galveston, by tendering his resignation as chief engineer of the Galveston Fire Department. In 1874 the New Orleans, Jackson & Great Northern Railroad was reorganized as the New Orleans, St. Louis & Chicago Railroad.

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

In his newly adopted city Burke developed a friendship with

In his newly adopted city Burke developed a friendship with Louis A. Wiltz

Louis Alfred Wiltz (January 21, 1843 – October 16, 1881) was an American politician from the state of Louisiana. He served as 29th Governor of Louisiana from 1880 to 1881 and before that time was mayor of New Orleans, lieutenant governor of L ...

, at the time, a politically ambitious banker. Burke became deeply involved within Democratic Conservative and white supremacist political circles in New Orleans. In 1872, Burke ran as the Democratic nominee for the city council position of Administrator of Improvements. The nomination of an independent candidate split the conservative vote allowing a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

to win the post. The 1872 election was not a total loss for Burke, his political mentor, Wiltz, was elected mayor of New Orleans

The post of Mayor of the City of New Orleans (french: Maire de La Nouvelle-Orléans) has been held by the following individuals since New Orleans came under American administration following the Louisiana Purchase — the acquisition by the U.S. ...

. Over the next decade Burke would become a crucial operative in the rise of the New Orleans Democratic machine. In September 1874 Burke was one of the key figures in the uprising and attempted coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

against the racially integrated elected government, known as the Battle of Liberty Place

The Battle of Liberty Place, or Battle of Canal Street, was an attempted insurrection and coup d'etat by the Crescent City White League against the Reconstruction Era Louisiana Republican state government on September 14, 1874, in New Orleans ...

. During the coup, organized by the Crescent City White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party political organizing. Its f ...

, armed men shot firearms and cannons throughout the city in an attempt to terrorize the Republican state leaders from office. Burke was appointed State Registrar of Voters by the insurgency leadership. The insurgency lasted three days, with approximately 13 deaths and at least 70 injuries incurred. The arrival of federal troops restored the previous administration. Nevertheless, tensions within the city of New Orleans remained high for weeks. In October, at a New Orleans intersection, Burke attempted to assault the then Governor William Pitt Kellogg

William Pitt Kellogg (December 8, 1830 – August 10, 1918) was an American lawyer and Republican Party politician who served as a United States Senator from 1868 to 1872 and from 1877 to 1883 and as the Governor of Louisiana from 1873 to 1877 du ...

. The altercation escalated into an exchange of pistol fire between the two. Although no one was injured, the attack resulted in the arrest of Burke. At the governor's request, as a sign of peace, Burke was eventually released. In November of that same year Burke again ran for Administrator of Improvements. This time he won. Two years later Burke guided Francis T. Nicholls

Francis Redding Tillou Nicholls (August 20, 1834January 4, 1912) was an American attorney, politician, judge, and a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He served two terms as the 28th Governor of L ...

in his election campaign for governor. The results of this election were in dispute, with both sides claiming victory and accusing the other side of voter fraud. Overshadowing this election was the disputed presidential election of 1876. Burke then went to Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

to take part in the so-called Compromise of 1877; which confirmed a win for the Republican presidential candidate, a win for Louisiana's Democratic governor candidate, and guaranteed removal of federal troops from Louisiana. The Compromise also ratified Burke's friend, Wiltz, as the Lieutenant Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

. This accomplishment earned Burke much political clout. As a reward Burke was appointed State Tax Collector, considered one of the most lucrative offices within the state government.

In 1878, Burke ran for the office of state treasurer and had an easy victory. It became apparent to both Burke and Wiltz that Governor Nicholls aims did not coincide with theirs. The two then began to influence party delegates towards their goals. Because of the rift, Nicholls decided not to seek a second term. Delegates were also persuaded to extend the current term of the state treasurer's office from four to six years and to give the Louisiana Lottery a state charter for 25 years. The Democratic convention ended with Wiltz being the nominee for governor. In the election of 1879 voters elected Wiltz governor, ratified the extended term of the state treasurer's office, and confirmed the 25-year state charter for the Louisiana Lottery. The Louisiana Lottery would prove to be a lightning rod for controversy in the coming years.

Politics, journalism, and defending honor

One of the major critics of the Louisiana Lottery was Henry J. Hearsey, the editor of the ''New Orleans Democrat''. Burke and Charles T. Howard, spokesperson and the ''ipso facto'' power within the Louisiana Lottery, conspired to financially undermine the ''Democrat''. At the time the ''Democrat'' had an abundance of state scrip, earned through state printing contracts. For the most part, the ''Democrat'' used this scrip as cash to pay its bills and suppliers. In 1879 Howard brought suit in federal court questioning the use of state scrip in payment of state debts. The court ruled that the scrip had no legal value. The ''Democrat'', unable to satisfy its creditors and facing bankruptcy, was sold to a consortium, consisting of Burke, Howard, and others. Hearsey left the ''Democrat'' to become the editor-publisher of the New Orleans ''Daily States''. After the purchase was finalized a second judicial ruling reversed the first decision restoring the value of state scrip. Burke resumed control of the ''Democrat'' as its managing editor. Bad blood between both Burke and Hearsey resulted in a challenge to a duel from Hearsey. On January 25, 1880 both men faced off and exchanged pistol fire. At the conclusion of the duel, neither man was wounded and both considered their honor to be intact. In 1881, Burke bought out his partners and became the sole owner of the ''Democrat''. On December 4 of that same year, Burke bought the New Orleans ''Times''. He then combined the two newspapers into the '' Times-Democrat''. Burke's newspaper was used to advocate his view of the New South. The '' Daily Picayune'' was also highly critical of Burke and his cronies. One stinging article in 1882 accused Burke of improprieties with the treasury funds. Incensed, Burke challenged the editor of the ''Daily Picayune'', C. Harrison Parker, to a duel. Since Parker was challenged, dueling etiquette allowed Parker to select the dueling weapon of choice; Parker chose rifles, but on the actual day of the duel he rethought his decision and chose pistols. Parker was a better shot than Burke's previous opponent and succeeded in seriously wounding Burke in his right thigh.Cotton Centennial

In 1882, the National Cotton Planters Association proposed the idea of a "

In 1882, the National Cotton Planters Association proposed the idea of a "World Cotton Centennial

The World Cotton Centennial (also known as the World's Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition) was a World's Fair held in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States in 1884. At a time when nearly one third of all cotton produced in the United Sta ...

". The organization called on New Orleans and other southern cities to bid for the honor of hosting the event. The proposal was not well received by southern cities still recovering from the aftermath of the Civil War. In order to stir up more publicity for the idea the National Cotton Planters Association in 1883 succeeded in having Senator Augustus Hill Garland

Augustus Hill Garland (June 11, 1832 – January 26, 1899) was an American lawyer and Democratic politician from Arkansas, who initially opposed Arkansas' secession from the United States, but later served in both houses of the Congres ...

of Arkansas introduce a bill in the US Senate to encourage the holding of a World's Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in 1884. This bill was approved by both houses of Congress. With public sentiment improving, a committee was formed. Commissioners and alternate commissioners from several states were to be appointed by the President. A governing body of thirteen directors was provided, six of whom were named by the President on the recommendation of the association and seven by him on that of a majority of the subscribers in the city in which the event was sponsored. With the future of the event becoming more of a reality, funding within the city of New Orleans started to grow. Burke's newspaper, the ''Times-Democrat'' was the first to pledge $5,000 towards the exposition. When $325,000 in pledges had been achieved the committee directors offered Burke the position of the exposition's director-general with a salary of $25,000. Burke initially refused, stating that his duties as both a newspaper editor and state treasurer would not allow enough time. Burke finally accepted when the committee directors appealed to his southern pride by hinting that they might have to include in their search — a Northerner. He refused the salary of $25,000, but accepted a salary of only $10,000 a year, which he directed should be invested in exhibition stock, to be later presented to the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Louisiana. Burke, once in command, proceeded to expand the idea of a merely local or even national exhibition into one which should embrace the entire world. With less than the needed funding, he began the erection of a building costing $325,000. While meeting much opposition to his plans, Burke, nevertheless forged ahead. Franklin C. Morehead, the perennial president of the National Cotton Planters Association and editor-publisher of its official chronicle, the ''Planters Journal'', was appointed to travel and interest state governments, manufacturing firms and foreign countries. Burke went to Washington in May, 1884, and succeeded in having a bill in Congress passed loaning $1,000,000, to be paid from the receipts of the exposition, if there were any surplus over expenses. The sum of $100,000 was also granted to the exposition fund by the Louisiana Legislature, for Congress had tied up its loan by a restrictive clause making the fund available only when $500,000 had been raised from other sources. Finally by August, 1884, a total of one million and a half was in sight. Of this amount $5,000 was to be given to each state and territory to be expended under the direction of its governor by a commission nominated by him and appointed by the President of the United States. These state exhibits thus came to be the strongest feature of the entire exhibition. The space allotted in advance for these state exhibits was soon found to be inadequate for the elaborate displays which resulted from the momentum given to this feature by the $5,000 appropriation, and it became necessary to erect a second building as large as the first. The publicity from the exposition propelled Burke into a second term as state treasurer in the election of 1884. With great fanfare the exposition opened on December 16, 1884. Despite the generous donation from Congress, cost overruns and an aura of funding misappropriations contributed to the financial failure of the exposition. Burke, foreseeing the inevitable, resigned his directorship three weeks before the enterprise was forced to an early closing on June 2, 1885.

Honduras and treasury scandal

Honduras was one of threeCentral America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

n countries to exhibit at the exposition. While their display was modest in comparison to others, their exhibit was highlighted by a personal visit to the exposition by Honduran President Luis Bográn

Luis Bográn Barahona (3 June 1849 – 9 July 1895) was a president of Honduras, who served two consecutive terms from 30 November 1883 to 30 November 1891. He was born in the northern Honduran department of Santa Bárbara on 3 June 1849 to S ...

. During this visit Bográn's host was Burke. Bográn was impressed by Burke's personality. The two became fast friends. Bográn was looking for someone to market the wealth of natural resources Honduras had to offer the world. Burke envisioned New Orleans as being the primary importing port for all of Central America's exports. In 1886 as an inducement to Burke, Bográn offered two large mining concessions along the Jalán and Guayape

Guayape is a municipality in the west of the Honduran department of Olancho, west of Salamá, south of Yocón and north of Concordia.

Guayape is divided into three huge territories. Some even covering the river.

The lands are divided by the ...

rivers in return for Burke's promise to help build an industrial school in Tegucigalpa

Tegucigalpa (, , ), formally Tegucigalpa, Municipality of the Central District ( es, Tegucigalpa, Municipio del Distrito Central or ''Tegucigalpa, M.D.C.''), and colloquially referred to as ''Tegus'' or ''Teguz'', is the capital and largest city ...

, Honduras' capital city. Burke accepted and visited Honduras at least twice between 1886 and 1888. In 1888 a reform-minded opposition succeeded in defeating Burke.

The time Burke had used in connection with his position as state treasurer was now applied to develop his mining ventures. In 1889 Burke undertook a trip to London to secure financing for a modern mining operation. While in London his successor, William Henry Pipes, discovered significant discrepancies in amount of funds available in the state treasury. Burke was considered a primary suspect of this embezzlement. From London, Burke denied these allegations and stated he intended to return to New Orleans to confront his accusers. After reviewing the evidence on hand, a grand jury handed down nineteen indictments against Burke. The evidence indicated that Burke had failed to destroy state bonds which had been redeemed and issued additional baby bonds without authorization. Sources place the amount of missing treasury funds anywhere from $64,000 to $2 million. In early December, Burke decided not to return to New Orleans and was later personally welcomed by President Bográn to Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Burke did not come empty-handed; he had succeeded in acquiring financing of $8 million for his mining venture. Arresting Burke was not an issue, because Honduras had not yet formalized a set of extradition treaties with the U.S. Burke's financial fortunes did not appear to fare well in Honduras. Burke had to contend with a number of financial panics in both

Burke's financial fortunes did not appear to fare well in Honduras. Burke had to contend with a number of financial panics in both London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

and Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

which caused investors to back out. He was also challenged with inclement weather and regime changes. In November 1893 Burke supported the losing side in a series of military skirmishes against Policarpo Bonilla

José Policarpo Bonilla Vasquez (1858–1926) was Dictator of Honduras between 22 February 1894 and 1 February 1895. Then elected as President for the period between 1 February 1895 and 1 February 1899.

Biography

He was born on 17 March 185 ...

. Burke and Domingo Vásquez

Domingo Vásquez (1846–1909) was President of Honduras 7 August 1893 – 22 February 1894. He lost power as a result of Honduras being defeated in a war with Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the large ...

had to flee to neighboring El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south b ...

. Eventually Burke came to terms with Bonilla and returned. During this same period of political upheaval, the opponents of the Louisiana Lottery succeeded in getting Congress to outlaw the interstate transportation of lottery tickets or lottery advertisements. The U.S. Supreme Court then affirmed that position. Instead of shutting down, the Louisiana Lottery decided to transfer its operations from New Orleans to Honduras. Very little is known, if Burke had any influence in steering the Louisiana Lottery to move to Honduras.

In June 1904, Burke accepted a position as the assistant superintendent and auditor of the Honduras Interoceanic Railway, one of the government's nationalized railroads. He held this position until August 1906. From 1912 to 1926, Burke held various positions within the National Railway of Honduras, also known as El Ferrocarril Nacional de Honduras, another nationalized railroad. In February 1926 Burke's associates back in New Orleans succeeded in nullifying all of his indictments. Even though Burke was vindicated, he decided to remain in Honduras. In 1928, Burke was on hand to greet Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

who was on a goodwill flight through Central America. This was not Burke's first encounter with a famous aviator. In 1919, Burke had unknowingly hired local Lisandro Garay as a driver. Garay would later become famous as an aviator in his own right, picking up the moniker — the "Honduran Lindbergh."

Death and division of estate

Burke died on September 24, 1928 at the Hotel Ritz in Tegucigalpa. He was predeceased by his wife Susan Elizabeth (Gaines) by more than a decade. She died July 21, 1916. Burke's only son, and only child, Lindsey, died in theCongo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leopo ...

more than two decades before Burke. In 1895, Lindsey had volunteered for service in the ''Force Publique

The ''Force Publique'' (, "Public Force"; nl, Openbare Weermacht) was a gendarmerie and military force in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1885 (when the territory was known as the Congo Free State), through the period of ...

'' in the Congo Free State, where he was commissioned as a lieutenant. About a year later, he was killed when he and three other officers were leading a contingent of fifty men to suppress an uprising of African natives. The men scattered, when natives ambushed their party; Lindsey, with the other three officers, fought until they were hacked down and slashed to pieces. Burke bequeathed half of his property to the government of Honduras, the remainder to relatives in the U.S. Because of measures taken by the Honduran government, Burke's heirs in the U.S. received nothing.

See also

* James "Honest Dick" Tate – aKentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

state Treasurer who also fled the country once his fraud was discovered.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Burke, Edward 1839 births 1928 deaths State treasurers of Louisiana Politicians from Louisville, Kentucky Louisiana Democrats People of Texas in the American Civil War American people of Irish descent American expatriates in Honduras Criminals from Louisiana Politicians convicted of embezzlement Fugitives wanted by the United States American duellists Louisiana politicians convicted of crimes