Eastern Atakapa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Atakapa Sturtevant, 659 or Atacapa were an

Atakapa-speaking peoples are called Atakapan, while Atakapa refers to a specific tribe. Atakapa-speaking peoples were divided into bands which were represented by

Atakapa-speaking peoples are called Atakapan, while Atakapa refers to a specific tribe. Atakapa-speaking peoples were divided into bands which were represented by

"Iberia Parish was once part of Attakapas District"

, ''Daily Advertiser,'' 25 November 1997 (retrieved 8 June 2009). They are named for the

Atakapa

Atakapa

Louis LeClerc Milfort, a Frenchman who spent 20 years living with and traveling among the

Louis LeClerc Milfort, a Frenchman who spent 20 years living with and traveling among the

indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the nor ...

, who spoke the Atakapa language

Atakapa (,Sturtevant, 659 natively ''Yukhiti'') is an extinct language isolate native to southwestern Louisiana and nearby coastal eastern Texas. It was spoken by the Atakapa people (also known as ''Ishak'', after their word for "the people"). Th ...

and historically lived along the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

in what is now Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

and Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

. They included several distinct bands.

Choctaw people

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

used the term ''Atakapa'', which was adopted by European settlers adopted the term. The Atakapa called themselves the Ishak , which translates as "the people."

Within the Ishak there were two moieties which the Ishak identified as "The Sunrise People" and "The Sunset People".

After 1762, when Louisiana was transferred to Spain following French defeat in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, little was written about the Atakapa as a people. Due to a high rate of deaths from infectious epidemics of the late 18th century, they ceased to function as a people. Survivors generally joined the Caddo

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, wh ...

, Koasati

The Coushatta ( cku, Koasati, Kowassaati or Kowassa:ti) are a Muskogean-speaking Native American people now living primarily in the U.S. states of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas.

When first encountered by Europeans, they lived in the territor ...

, and other neighboring nations, although they kept some traditions. Some culturally distinct Atakapan descendants survived into the early 20th century.

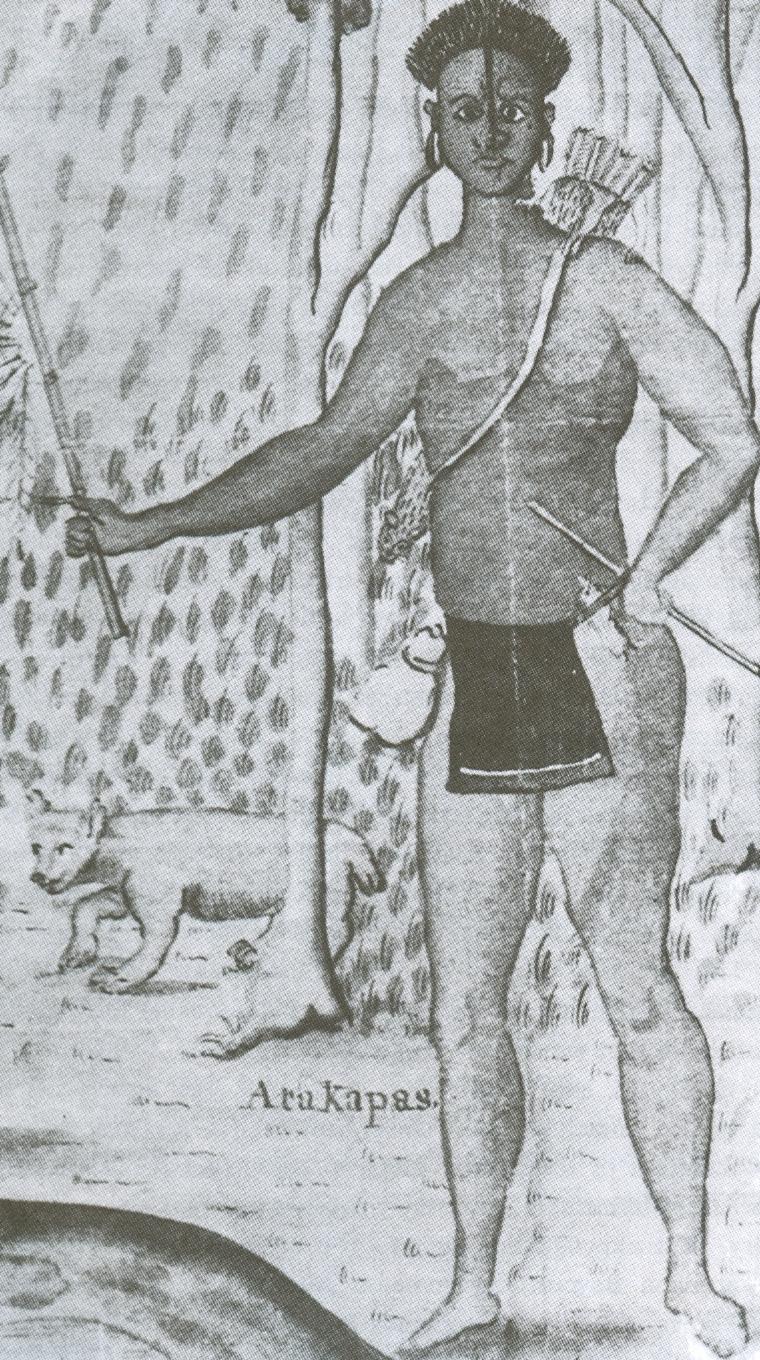

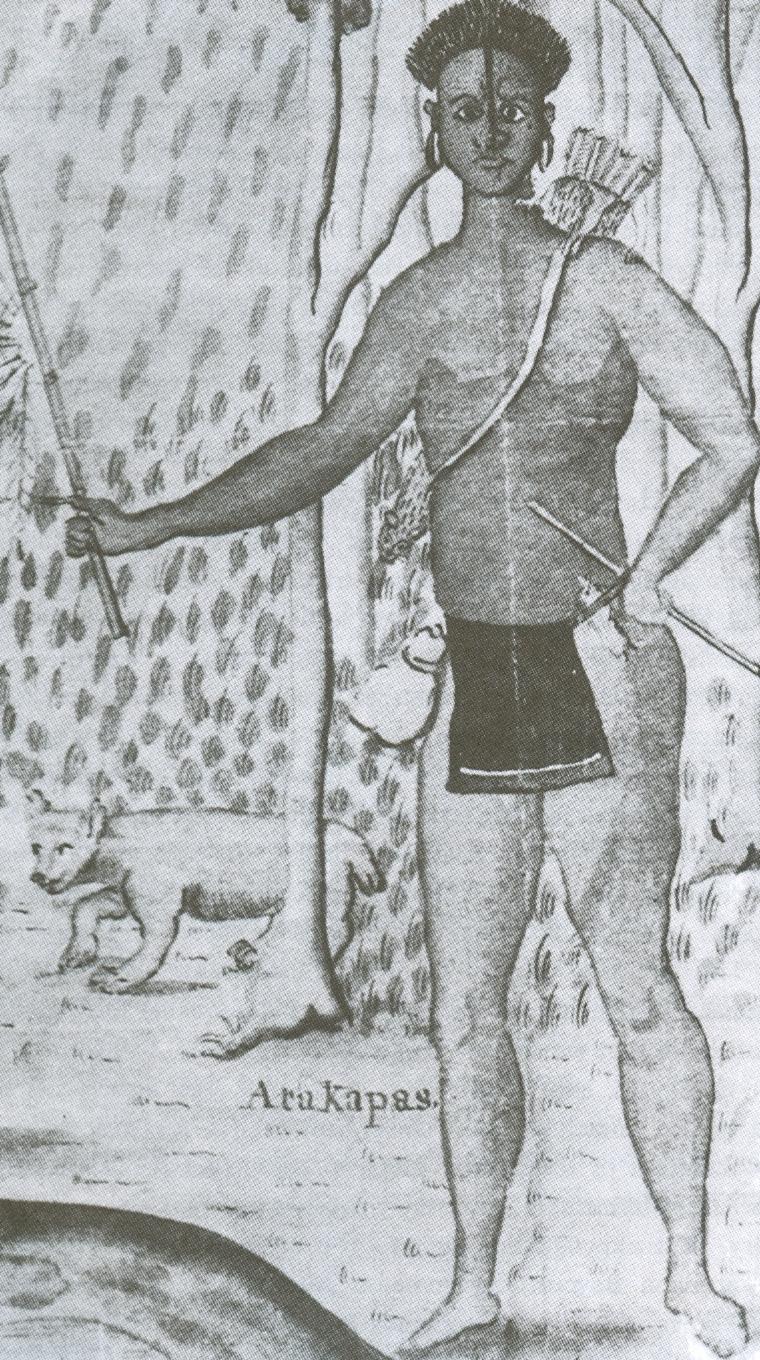

Name

Their name was also spelled ''Attakapa'', ''Attakapas'', or ''Attacapa''. The Choctaw used this term, meaning "man-eater", for their practice of ritual cannibalism. Europeans encountered the Choctaw first during their exploration, and adopted their name for this people to the west. The peoples lived in river valleys, along lake shores, and coasts from present-day Vermilion Bay,Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

to Galveston Bay, Texas

Galveston Bay ( ) is a bay in the western Gulf of Mexico along the upper coast of Texas. It is the seventh-largest estuary in the United States, and the largest of seven major estuaries along the Texas Gulf Coast. It is connected to the Gulf of ...

.

Subdivisions or bands

totem

A totem (from oj, ᑑᑌᒼ, italics=no or ''doodem'') is a spirit being, sacred object, or symbol that serves as an emblem of a group of people, such as a family, clan, lineage, or tribe, such as in the Anishinaabe clan system.

While ''the wo ...

s, such as snake, alligator, and other natural life.

Eastern Atakapa

The Eastern Atakapa (Hiyekiti Ishak, "Sunrise People") groups lived in present-dayAcadiana

Acadiana ( French and Louisiana French: ''L'Acadiane''), also known as the Cajun Country (Louisiana French: ''Le Pays Cadjin'', es, País Cajún), is the official name given to the French Louisiana region that has historically contained mu ...

parishes in southwestern Louisiana and are organized as three major regional bands:

* The Ciwāt or Alligator Band lived along the Vermilion River and near Vermilion Bay in southwestern Iberia Parish

Iberia Parish (french: Paroisse de l'Ibérie, es, Parroquia de Iberia) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. At the 2020 census, it had a population of 69,929; the parish seat is New Iberia.

The parish was formed in 1868 during ...

and southeastern Vermilion Parish

Vermilion Parish (french: Paroisse de Vermillion) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana, created in 1844. The parish seat is Abbeville. Vermilion Parish is part of the Lafayette metropolitan statistical area, and located in southern ...

in south central Louisiana. This inlet

An inlet is a (usually long and narrow) indentation of a shoreline, such as a small arm, bay, sound, fjord, lagoon or marsh, that leads to an enclosed larger body of water such as a lake, estuary, gulf or marginal sea.

Overview

In marine geogra ...

of the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

is separated from it by Marsh Island; they also occupied a portion of the Louisiana mainland in southeastern Vermilion Parish. The alligator

An alligator is a large reptile in the Crocodilia order in the genus ''Alligator'' of the family Alligatoridae. The two extant species are the American alligator (''A. mississippiensis'') and the Chinese alligator (''A. sinensis''). Additiona ...

was very important to this band. In addition to consuming its meat as food, they used its oil for cooking and to treat minor arthritis

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In som ...

and eczema

Dermatitis is inflammation of the Human skin, skin, typically characterized by itchiness, erythema, redness and a rash. In cases of short duration, there may be small blisters, while in long-term cases the skin may become lichenification, thick ...

symptoms. They used its scales as arrowheads.

* The Otse, Teche Band, or Snake Band lived on the prairies and coastal marshes in the Mermentau River

The Mermentau River (french: Rivière Mermentau) is a river in southern Louisiana in the United States. It enters the Gulf of Mexico between Calcasieu Lake and Vermilion Bay on the Chenier Coastal Plain.

The Mermentau River supplies freshwater ...

watershed, along the Bayou Nezpique Nezpique River (locally pronounced , translated to ''"tattooed nose bayou"'') is a small river located in the Mermentau River basin of south Louisiana, USA. The river is long and is navigable by small shallow-draft boats for of lower course.

T ...

, Bayou des Cannes

Bayou des Cannes (pronounced "DAI KAIN", translated to ''"bayou of the reeds"'' or ''"bayou of the stalks"'' ) is a waterway in the Mermentau River basin of southern Louisiana. The bayou is longU.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset ...

, and Bayou Plaquemine Brule

Bayou Plaquemine Brulé (; historically spelled ''Plakemine''; translated to ''"burnt persimmon bayou"'') is a waterway in the Mermentau River basin of south Louisiana. The bayou is longU.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-res ...

, containing the freshwater Grand

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

* Grand Mixer DXT, American turntablist

* Grand Puba (born 1966), American rapper

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma

* Grand, Vosges, village and commu ...

and White lakes, and around St. Martinville

St. Martinville (french: Saint-Martin)Jack A. Reynolds. "St. Martinville" entry i"Louisiana Placenames of Romance Origin."LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses #7852. 1942. p. 480. is a city in and the parish seat of St. Martin Parish, Louisiana ...

on Bayou Teche in present-day St. Martin, Lafayette

Lafayette or La Fayette may refer to:

People

* Lafayette (name), a list of people with the surname Lafayette or La Fayette or the given name Lafayette

* House of La Fayette, a French noble family

** Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757� ...

, St. Landry, St. Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

, Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

and Evangeline

''Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie'' is an epic poem by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, written in English and published in 1847. The poem follows an Acadian girl named Evangeline and her search for her lost love Gabriel, set during t ...

parishes in southern Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

.Bradshaw, Jim"Iberia Parish was once part of Attakapas District"

, ''Daily Advertiser,'' 25 November 1997 (retrieved 8 June 2009). They are named for the

snake

Snakes are elongated, Limbless vertebrate, limbless, carnivore, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales. Ma ...

, which symbolizes the winding and twisting course of Bayou Teche

Bayou Teche (Louisiana French: ''Bayou Têche'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 20, 2011 waterway of great cultural significance in south central Louisiana in t ...

.

* The Tsikip, Appalousa (Opelousa), Opelousas Band ("Blackleg") or Heron Band, painted their lower legs and feet black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

during mourning ceremonies, mimicking the long black legs of the heron

The herons are long-legged, long-necked, freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae, with 72 recognised species, some of which are referred to as egrets or bitterns rather than herons. Members of the genera ''Botaurus'' and ''Ixobrychus ...

. Before European contact in the 18th century, they lived between the Atchafalaya River

The Atchafalaya River ( french: La Rivière Atchafalaya, es, Río Atchafalaya) is a distributary of the Mississippi River and Red River in south central Louisiana in the United States. It flows south, just west of the Mississippi River, and ...

and Sabine River (at the present-day border of Texas-Louisiana) to the west of the lower Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. Later they were centered in the area around present-day Opelousas, Louisiana :''Opelousas is also a common name of the flathead catfish.''

Opelousas (french: Les Opélousas; Spanish: ''Los Opeluzás'') is a small city and the parish seat of St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, United States. Interstate 49 and U.S. Route 190 were ...

and the prairies around St. Landry Parish

St. Landry Parish (french: Paroisse de Saint-Landry) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2010 Census, the population was 83,384. The parish seat is Opelousas. The parish was established in 1807.

St. Landry Parish co ...

. They were at times associated with the neighboring Eastern Atakapa and Chitimacha

The Chitimacha ( ; or ) are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans who live in the U.S. state of Louisiana, mainly on their reservation in St. Mary Parish near Charenton on Bayou Teche. They are the only Indigenous people in the s ...

peoples. They were warlike and preyed on neighbors to defend their own territory. In 1760 Chief ''Kinemo'' of the Eastern Atakapa sold the tribal lands between the Vermilion River and Bayou Teche to Frenchman Gabriel Fuselier de la Claire; the angry Appalousa exterminated the Eastern Atakapa bands for selling off communal lands. The Opelousa Band reportedly spoke the Eastern Atakapan dialect.

Western Atakapa

The Western Atakapa (Hikike Ishak, "Sunset People") resided in southeastern Texas. They were organized as follows. *Atakapa (proper) groups, divided into major regional bands: ** The Katkoc or Eagle Band (named after theeagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just ...

s in the area), were also known as Calcasieu Band, because they were living along Calcasieu River

The Calcasieu River ( ; french: Rivière Calcasieu) is a river on the Gulf Coast in southwestern Louisiana. Approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 20, ...

between the Calcasieu Lake

Calcasieu Lake is a brackish lake located in southwest Louisiana, United States, located mostly within Cameron Parish. The Lake, also known as Big Lake to the local population, is paralleled on its west shore by Louisiana Highway 27, and is loc ...

in southwest Louisiana and Sabine Lake

Sabine Lake is a bay on the Gulf coasts of Texas and Louisiana, located approximately east of Houston and west of Baton Rouge, adjoining the city of Port Arthur. The lake is formed by the confluence of the Neches and Sabine Rivers and conne ...

on the Louisiana-Texas border.

** The Red Bird Band, lived on the prairies and coastal areas of what is now Cameron Parish, in South Western Louisiana; they were represented by the cardinal or red bird

Red Bird (–16 February 1828) was a leader of the Winnebago (or Ho-Chunk) Native American tribe. He was a leader in the Winnebago War of 1827 against Americans in the United States making intrusions into tribal lands for mining. He was f ...

.

** The Niāl or Panther Band, lived in the areas around the Sabine River of South East Texas, they took the panther

Panther may refer to:

Large cats

*Pantherinae, the cat subfamily that contains the genera ''Panthera'' and ''Neofelis''

**'' Panthera'', the cat genus that contains tigers, lions, jaguars and leopards.

*** Jaguar (''Panthera onca''), found in So ...

as their totem.

* The Akokisa

The Akokisa were the indigenous tribe that lived on Galveston Bay and the lower Trinity and San Jacinto rivers in Texas, primarily in the present-day Greater Houston area.Campbell, Thomas N. "Akokisa Indians.''The Handbook of Texas Online.''(re ...

, Arkokisa, or Orcoquiza ("river people"), westernmost Atakapa tribe, lived in the mid-18th century in five villages along the lower course of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

and San Jacinto rivers and the northern and eastern shores of Galveston Bay

Galveston Bay ( ) is a bay in the western Gulf of Mexico along the upper coast of Texas. It is the seventh-largest estuary in the United States, and the largest of seven major estuaries along the Texas Gulf Coast. It is connected to the Gulf of ...

in present-day Texas. In 1805, their surviving people were reported to be living in villages on the lower Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

and Neches rivers.

*The Quasmigdo, better known as Bidai

The Bidai were a tribe of Atakapa Indians from eastern Texas.Sturtevant, 659

History

Their oral history says that the Bidai were the original people in their region.Caddo language

Caddo is a Native American language, the traditional language of the Caddo Nation. It is critically endangered, with no exclusively Caddo-speaking community and only 25 speakers as of 1997 who acquired the language as children outside school ins ...

name meaning "brushwood"), were based around Bedias Creek

Bedias Creek is a creek in Texas. The creek rises in Madison County and flows east into Houston County, where it empties into the Trinity River.

See also

*List of rivers of Texas

The list of rivers of Texas is a list of all named waterways, ...

, ranging from the Brazos River

The Brazos River ( , ), called the ''Río de los Brazos de Dios'' (translated as "The River of the Arms of God") by early Spanish explorers, is the 11th-longest river in the United States at from its headwater source at the head of Blackwater Dr ...

to Neches River

The Neches River () begins in Van Zandt County west of Rhine Lake and flows for through the piney woods of east Texas, defining the boundaries of 14 counties on its way to its mouth on Sabine Lake near the Rainbow Bridge. Two major reservoirs, ...

, Texas.

*The Deadose

The Deadose were a Native American Tribe in present-day Texas closely associated with the Jumano, Yojuane, Bidai and other groups living in the Rancheria Grande of the Brazos River in eastern Texas in the early 18th century.

Like other groups ...

, a band of Bidai that separated in the early 18th century, lived north of the other Bidai between the confluence of the Angelina River

The Angelina River is formed by the junction of Barnhardt and Shawnee creeks northwest of Laneville in southwest central Rusk County, Texas.

The river flows southeast for and forms the boundaries between Cherokee and Nacogdoches, Angelina and ...

and Neches River and the upper end of Galveston Bay in east-central Texas. Around 1720 they moved westward between the Brazos and Trinity rivers; later they settled near missions on the San Gabriel River (with the Bidai and Akokisa) in the Texas Hill Country

The Texas Hill Country is a geographic region of Central and South Texas, forming the southeast part of the Edwards Plateau. Given its location, climate, terrain, and vegetation, the Hill Country can be considered the border between the Ameri ...

. Between 1749 and 1751 they gathered (with the Akokisa, Orcoquiza, Bidai, and Patiri) at the short-lived San Ildefonso Mission near the mouth of Brushy Creek; some settled near the Alamo Mission in San Antonio

The Battle of the Alamo (February 23 – March 6, 1836) was a pivotal event in the Texas Revolution. Following a 13-day siege, Mexican troops under President General Antonio López de Santa Anna reclaimed the Alamo Mission near San Ant ...

. In the second half of the 18th century, the Deadose were closely associated with Tonkawa

The Tonkawa are a Native American tribe indigenous to present-day Oklahoma. Their Tonkawa language, now extinct, is a linguistic isolate.

Today, Tonkawa people are enrolled in the federally recognized Tonkawa Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma.

...

n groups (Ervipiame The Ervipiame or Hierbipiame were a Native people of modern Coahuila and Texas.

Beginning in the 16th century Spanish settlement in what is today Northern Mexico and the accompanying diseases and slave raiding to supply ranches and mines with Nativ ...

(?), Mayeye

The Mayeye were a Tonkawa language–speaking Native American people, who once lived in southeastern Texas. Coastal Mayeyes likely were absorbed into Karankawa communities. Inland Mayeyes likely joined larger Tonkawa communities.

Name

Their nam ...

, and Yojuane

The Yojuane were a people who lived in Texas in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. They were closely associated with the Jumano and may have also been related to the Tonkawa. They have no connection to the Yowani in Texas, a Choctaw band.

Etym ...

). Suffering high mortality from epidemics of measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, survivors joined kindred Bidai, Akokisa and Tonkawa. They lost their distinctive tribal identity in the latter part of the 18th century.

* The Patiri or Petaros lived north of the San Jacinto River valley between the Bidai to the north and the Akokisa in the south of Texas. This places them in the Piney Woods

The Piney Woods is a temperate coniferous forest terrestrial ecoregion in the Southern United States covering of East Texas, southern Arkansas, western Louisiana, and southeastern Oklahoma. These coniferous forests are dominated by several spec ...

of East Texas

East Texas is a broadly defined cultural, geographic, and ecological region in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Texas that comprises most of 41 counties. It is primarily divided into Northeast and Southeast Texas. Most of the region consi ...

, west of the Trinity River in the area between Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 in ...

and Huntsville

Huntsville is a city in Madison County, Limestone County, and Morgan County, Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Madison County. Located in the Appalachian region of northern Alabama, Huntsville is the most populous city in th ...

. Little is known about them; perhaps they were a southern Bidai band.

* The Tlacopsel, Acopsel, or Lacopspel — it is believed that they lived in the same general area as the kindred Bidai and Deadose. The location of their settlements in southeast Texas are unknown. They are known only from Spanish documents of the eighteenth century, when they were referred to for requesting missions from the Spanish in east central Texas.

Atakapa language

TheAtakapa language

Atakapa (,Sturtevant, 659 natively ''Yukhiti'') is an extinct language isolate native to southwestern Louisiana and nearby coastal eastern Texas. It was spoken by the Atakapa people (also known as ''Ishak'', after their word for "the people"). Th ...

was a language isolate

Language isolates are languages that cannot be classified into larger language families. Korean and Basque are two of the most common examples. Other language isolates include Ainu in Asia, Sandawe in Africa, and Haida in North America. The num ...

, once spoken along the Louisiana and East Texas coast and believed extinct since the mid-20th century. John R. Swanton

John Reed Swanton (February 19, 1873 – May 2, 1958) was an American anthropologist, folklorist, and linguist who worked with Native American peoples throughout the United States. Swanton achieved recognition in the fields of ethnology and et ...

in 1919 proposed a Tunican language family that would include Atakapa, Tunica, and Chitimacha

The Chitimacha ( ; or ) are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans who live in the U.S. state of Louisiana, mainly on their reservation in St. Mary Parish near Charenton on Bayou Teche. They are the only Indigenous people in the s ...

. Mary Haas

Mary Rosamond Haas (January 23, 1910 – May 17, 1996) was an American linguist who specialized in North American Indian languages, Thai, and historical linguistics. She served as president of the Linguistic Society of America. She was elected a ...

later expanded this into the Gulf language family with the addition of the Muskogean languages

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

. As of 2001, linguists generally do not consider these proposed families as proven.

History

Atakapa

Atakapa oral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information about individuals, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people wh ...

says that they originated from the sea. An ancestral prophet laid out the rules of conduct.Sturtevant, 662.

The first European contact with the Atakapa may have been in 1528 by survivors of the Spanish Pánfilo de Narváez

Pánfilo de Narváez (; 147?–1528) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' and soldier in the Americas. Born in Spain, he first embarked to Jamaica in 1510 as a soldier. He came to participate in the conquest of Cuba and led an expedition to Camagüey ...

expedition. These men in Florida had made two barges, in an attempt to sail to Mexico, and these were blown ashore on the Gulf Coast. One group of survivors met the Karankawa

The Karankawa were an Indigenous people concentrated in southern Texas along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, largely in the lower Colorado River and Brazos River valleys."Karankawa." In ''Cassell's Peoples, Nations and Cultures,'' edited by John ...

, while the other probably landed on Galveston Island

Galveston Island ( ) is a barrier island on the Texas Gulf Coast in the United States, about southeast of Houston. The entire island, with the exception of Jamaica Beach, is within the city limits of the City of Galveston in Galveston County.

T ...

. The latter recorded meeting a group who called themselves the Han, who may have been the Akokisa

The Akokisa were the indigenous tribe that lived on Galveston Bay and the lower Trinity and San Jacinto rivers in Texas, primarily in the present-day Greater Houston area.Campbell, Thomas N. "Akokisa Indians.''The Handbook of Texas Online.''(re ...

.

18th century

In 1703,Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville (; ; February 23, 1680 – March 7, 1767), also known as Sieur de Bienville, was a French colonial administrator in New France. Born in Montreal, he was an early governor of French Louisiana, appointed four ...

, the French governor of ''La Louisiane

Louisiana (french: La Louisiane; ''La Louisiane Française'') or French Louisiana was an administrative district of New France. Under French control from 1682 to 1769 and 1801 (nominally) to 1803, the area was named in honor of King Louis XIV, ...

'', sent three men to explore the Gulf Coast west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. The seventh nation they encountered were the Atakapa, who captured, killed and cannibalized one member of their party. In 1714 this tribe was one of 14 that were recorded as coming to Jean-Michel de Lepinay, who was acting French governor of Louisiana between 1717 and 1718, while he was fortifying Dauphin Island, Alabama

Dauphin Island is an island town in Mobile County, Alabama, United States, on a barrier island of the same name, in the Gulf of Mexico. It incorporated in 1988. The population was 1,778 at the 2020 census, up from 1,238 at the 2010 census. The t ...

.

The Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

told the French settlers about the "People of the West," who represented subdivisions or tribes. The French referred to them as ''les sauvages''. The Choctaw used the name ''Atakapa,'' meaning "people eater" (''hattak'' 'person', ''apa'' 'to eat'), for them. It referred to their practice of ritual cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

related to warfare.

A French explorer, Francois Simars de Bellisle Francois Simars de Bellisle (1695-1763) was a Frenchman who was shipwrecked on the Bolivar Peninsula, near present-day Galveston, Texas, in 1722. He had been sailing for New Orleans. He was captured by Akokisa natives, and had to subsist for som ...

, lived among the Atakapa from 1719 to 1721. He described Atakapa feasts including consumption of human flesh, which he observed firsthand. The practice of cannibalism likely had a religious, ritualistic basis. French Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

missionaries urged the Atakapa to end this practice.

The French historian Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz

Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz (1695?–1775)

lived in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

from 1718 to 1734. He wrote:

Louis LeClerc Milfort, a Frenchman who spent 20 years living with and traveling among the

Louis LeClerc Milfort, a Frenchman who spent 20 years living with and traveling among the Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsVermilion River and

In 1908, nine known Atakapa descendants were identified. Armojean Reon (ca. 1873–1925) of

In 1908, nine known Atakapa descendants were identified. Armojean Reon (ca. 1873–1925) of

The Atakapan ate shellfish and fish. The women gathered bird eggs, the American lotus (''

The Atakapan ate shellfish and fish. The women gathered bird eggs, the American lotus (''

"Atakapa-Ishak Trail"

, Lafayette, Louisiana website

Tribes in Louisiana

Handbook of Texas OnlineAtakapa-Ishak Nation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Atakapa People Native American history of Louisiana Native American history of Texas Native American tribes in Louisiana Native American tribes in Texas Unrecognized tribes in the United States

Bayou Teche

Bayou Teche (Louisiana French: ''Bayou Têche'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 20, 2011 waterway of great cultural significance in south central Louisiana in t ...

from the Eastern Atakapa Chief Kinemo. Shortly after that a rival Indian tribe, the Appalousa

The Appalousa (also Opelousa) were an indigenous American people who occupied the area around present-day Opelousas, Louisiana, west of the lower Mississippi River, before European contact in the eighteenth century. At various times in their histo ...

(Opelousas), coming from the area between the Atchafalaya and Sabine

The Sabines (; lat, Sabini; it, Sabini, all exonyms) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

The Sabines divide ...

rivers, exterminated the Eastern Atakapa. They had occupied the area between Atchafalaya River and ''Bayou Nezpique'' (Attakapas Territory).

William Byrd Powell (1799–1867), a medical doctor and physiologist

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical a ...

, regarded the Atakapan as cannibals. He noted that they traditionally flattened their skulls frontally and not occipitally, a practice opposite to that of neighboring tribes, such as the Natchez Nation

The Natchez (; Natchez pronunciation ) are a Native American people who originally lived in the Natchez Bluffs area in the Lower Mississippi Valley, near the present-day city of Natchez, Mississippi in the United States. They spoke a language ...

.

The Atakapa traded with the Chitimacha

The Chitimacha ( ; or ) are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans who live in the U.S. state of Louisiana, mainly on their reservation in St. Mary Parish near Charenton on Bayou Teche. They are the only Indigenous people in the s ...

tribe. In the early 18th century, some Atakapa married into the Houma tribe of Louisiana. Members of the Tunica-Biloxi

The Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe, ( tun, Yoroniku-Halayihku) formerly known as the Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe of Louisiana, is a federally recognized tribe of primarily Tunica and Biloxi people, located in east central Louisiana. Descendants of ...

tribe joined the Atakapa tribe in the late 18th century.

19th century

John R. Swanton

John Reed Swanton (February 19, 1873 – May 2, 1958) was an American anthropologist, folklorist, and linguist who worked with Native American peoples throughout the United States. Swanton achieved recognition in the fields of ethnology and et ...

recorded that only 175 Atakapa lived in Louisiana in 1805.

It is believed that most Western Atakapa tribes or subdivisions were decimated by the 1850s, mainly from infectious disease and poverty.

20th century

In 1908, nine known Atakapa descendants were identified. Armojean Reon (ca. 1873–1925) of

In 1908, nine known Atakapa descendants were identified. Armojean Reon (ca. 1873–1925) of Lake Charles, Louisiana

Lake Charles (French: ''Lac Charles'') is the fifth-largest incorporated city in the U.S. state of Louisiana, and the parish seat of Calcasieu Parish, located on Lake Charles, Prien Lake, and the Calcasieu River. Founded in 1861 in Calcasieu ...

, was noted as a fluent Atakapa speaker. In the 1920s, ethnologists Albert Gatshet and John Swanton studied the language and published ''A Dictionary of the Atakapa Language'' in 1932.

Culture

The Atakapan ate shellfish and fish. The women gathered bird eggs, the American lotus (''

The Atakapan ate shellfish and fish. The women gathered bird eggs, the American lotus (''Nelumbo lutea

''Nelumbo lutea'' is a species of flowering plant in the family Nelumbonaceae. Common names include American lotus, yellow lotus, water-chinquapin, and volée. It is native to North America. The botanical name ''Nelumbo lutea'' Willd. is the c ...

'') for its roots and seeds, as well as other wild plants. The men hunted deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the reindeer ...

, bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family Ursidae. They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats throughout the Nor ...

, and bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North Ame ...

, which provided meat, fat

In nutrition science, nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such chemical compound, compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers spec ...

, and hides. The women cultivated varieties of maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

. They processed the meats, bones and skins to prepare food for storage, as well as to make clothing, tent covers, tools, sewing materials, arrow cases, bridles and rigging for horses, and other necessary items for their survival.Sturtevant, 661.

The men made their tools for hunting and fishing: bows and arrows, fish spears with bone-tipped points, and flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start fir ...

-tipped spears. They used poisons to catch fish, caught flounder

Flounders are a group of flatfish species. They are demersal fish, found at the bottom of oceans around the world; some species will also enter estuaries.

Taxonomy

The name "flounder" is used for several only distantly related species, thou ...

by torchlight, and speared alligators

An alligator is a large reptile in the Crocodilia order in the genus ''Alligator'' of the family Alligatoridae. The two extant species are the American alligator (''A. mississippiensis'') and the Chinese alligator (''A. sinensis''). Additionall ...

in the eye. The people put alligator oil on exposed skin to repel mosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning " gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "li ...

es. The Bidai snared game and trapped animals in cane

Cane or caning may refer to:

*Walking stick or walking cane, a device used primarily to aid walking

*Assistive cane, a walking stick used as a mobility aid for better balance

*White cane, a mobility or safety device used by many people who are b ...

pens. By 1719, the Atakapan had obtained horses and were hunting bison from horseback. They used dugout canoe

A dugout canoe or simply dugout is a boat made from a hollowed tree. Other names for this type of boat are logboat and monoxylon. ''Monoxylon'' (''μονόξυλον'') (pl: ''monoxyla'') is Greek – ''mono-'' (single) + '' ξύλον xylon'' (t ...

s to navigate the bayous and close to shore, but did not venture far into the ocean.

In the summer, families moved to the coast. In winters, they moved inland and lived in villages of houses made of pole and thatch. The Bidai lived in bearskin tents. The homes of chiefs and medicine men were erected on earthwork mounds

A mound is an artificial heap or pile, especially of earth, rocks, or sand.

Mound and Mounds may also refer to:

Places

* Mound, Louisiana, United States

* Mound, Minnesota, United States

* Mound, Texas, United States

* Mound, West Virginia

* Moun ...

made by several previous cultures including the Mississippian.

Cultural heritage groups

Different groups claiming to be descendants of the Atakapa have created several organizations, and some have unsuccessfully petitioned Louisiana, Texas, and the United States for status as a recognized tribe. A member of the "Atakapa Indian de Creole Nation," claiming to be trustee, monarch, and deity, filed a number of lawsuits in federal court claiming, among other things, that the governments of Louisiana and the United States seek to "monopolize intergalactic foreign trade." The suits were dismissed as frivolous. Another group, the Atakapa Ishak Tribe of Southeast Texas and Southwest Louisiana, also called the Atakapa Ishak Nation, based inLake Charles, Louisiana

Lake Charles (French: ''Lac Charles'') is the fifth-largest incorporated city in the U.S. state of Louisiana, and the parish seat of Calcasieu Parish, located on Lake Charles, Prien Lake, and the Calcasieu River. Founded in 1861 in Calcasieu ...

obtained nonprofit status in 2008 as an "ethnic awareness" organization. They also refer to themselves as the Atakapa-Ishak Nation and met en masse on October 28, 2006. The Atakapas Ishak Nation of Southeast Texas and Southwest Louisiana unsuccessfully petitioned the US federal government for recognition on February 2, 2007.

These organizations are not federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

or state-recognized

State-recognized tribes in the United States are organizations that identify as Native American tribes or heritage groups that do not meet the criteria for federally recognized Indian tribes but have been recognized by a process established under ...

as Native American tribes.

Legacy

The names of present-day towns in the region can be traced to the Ishak; they are derived both from their language and from French transliteration of the names of their prominent leaders and names of places. The town ofMermentau

Mermentau is a village in Acadia Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 661 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Crowley Micropolitan Statistical Area.

History

In the last quarter of the 18th century, there was an Atakapa chie ...

is a corrupted form of the local chief ''Nementou''. ''Plaquemine,'' as in Bayou Plaquemine Brûlée and Plaquemines Parish

Plaquemines Parish (; French: ''Paroisse de Plaquemine'', Louisiana French: ''Paroisse des Plaquemines'', es, Parroquia de Caquis) is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 23,515 at the 2020 census, the parish ...

, is derived from the Atakapa word ''pikamin'', meaning "persimmon

The persimmon is the edible fruit of a number of species of trees in the genus ''Diospyros''. The most widely cultivated of these is the Oriental persimmon, ''Diospyros kaki'' ''Diospyros'' is in the family Ebenaceae, and a number of non-pers ...

". Bayou Nezpiqué was named for an Atakapan who had a tattooed nose. Bayou Queue de Tortue

In usage in the Southern United States, a bayou () is a body of water typically found in a flat, low-lying area. It may refer to an extremely slow-moving stream, river (often with a poorly defined shoreline), marshy lake, wetland, or creek. They ...

was believed to have been named for Chief ''Celestine La Tortue'' of the Atakapas nation. The name '' Calcasieu'' is a French transliteration of an Atakapa name: ''katkosh'', for "eagle", and ''yok'', "to cry".

The city of Lafayette, Louisiana

Lafayette (, ) is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana, and the most populous city and parish seat of Lafayette Parish, located along the Vermilion River. It is Louisiana's fourth largest incorporated municipality by population and the 234th- ...

, is planning a series of trails, funded by the Federal Highway Administration

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is a division of the United States Department of Transportation that specializes in highway transportation. The agency's major activities are grouped into two programs, the Federal-aid Highway Program a ...

, to be called the "Atakapa-Ishak Trail". It will consist of a bike trail connecting downtown areas along the bayous Vermilion and Teche, which are now accessible only by foot or boat., Lafayette, Louisiana website

See also

*USS Atakapa (ATF-149)

USS ''Atakapa'' (ATF-149) was an of fleet ocean tug. It was named after the Atakapa Native American tribe that once inhabited territory which is now southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas.

Construction history

The fleet ocean tug (ATF- ...

* Attakapas Parish

Notes

References

* Newcomb, William Wilmon, Jr. ''The Indians of Texas: From Prehistoric to Modern Times.'' Austin: University of Texas Press, 1972. . * Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Raymond D. Fogelson, volume editor. ''Handbook of North American Indians

The ''Handbook of North American Indians'' is a series of edited scholarly and reference volumes in Native American studies, published by the Smithsonian Institution beginning in 1978. Planning for the handbook series began in the late 1960s and ...

: Southeast.'' Volume 14. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. .

* Nezat, Jack Claude. ''The Nezat and Allied Families 1630–2007'', and ''The Nezat and Allied Families 1630-2020''. .

* Pritzer, Barry M. ''A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000: 286-7. .

External links

Tribes in Louisiana

Handbook of Texas Online

{{DEFAULTSORT:Atakapa People Native American history of Louisiana Native American history of Texas Native American tribes in Louisiana Native American tribes in Texas Unrecognized tribes in the United States