Eastern Approaches on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Eastern Approaches'' (1949) is a memoir of the early career of Fitzroy Maclean. It is divided into three parts: his life as a junior diplomat in Moscow and his travels in the Soviet Union, especially the forbidden zones of Central Asia; his exploits in the British Army and SAS in the North Africa theatre of war; and his time with

In September 1942 Maclean was ordered to

In September 1942 Maclean was ordered to

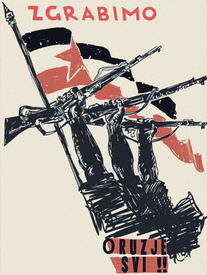

The final and longest section of the book covers Maclean's time in and around Yugoslavia, from the late summer of 1943 to the formation of the united government in March 1945. The Yugoslav front, also known as the Yugoslav People's Liberation War, had become important to the Allies by 1943, although the Partisans had been fighting for two years without any help. He lived closely with Tito and his troops and had the ear of Churchill, and as such his recommendations shaped the Allies' policy towards Yugoslavia.

The final and longest section of the book covers Maclean's time in and around Yugoslavia, from the late summer of 1943 to the formation of the united government in March 1945. The Yugoslav front, also known as the Yugoslav People's Liberation War, had become important to the Allies by 1943, although the Partisans had been fighting for two years without any help. He lived closely with Tito and his troops and had the ear of Churchill, and as such his recommendations shaped the Allies' policy towards Yugoslavia.

admiral's barge

dodging around them. Maclean was assigned a little

From Bari, he calculated that Tito would want to be directing the recapture of Belgrade, so he headed towards there himself, landing at

From Bari, he calculated that Tito would want to be directing the recapture of Belgrade, so he headed towards there himself, landing at

Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

and the Partisans in Yugoslavia.

Maclean was considered to be one of the inspirations for James Bond

A number of real-life inspirations have been suggested for James Bond (literary character), James Bond, the fictional character created in 1953 by British author, journalist and British Naval Intelligence, Naval Intelligence officer Ian Fleming (1 ...

, and this book contains many of the elements: remote travel, the sybaritic

Sybaris ( grc, Σύβαρις; it, Sibari) was an important city of Magna Graecia. It was situated in modern Calabria, in southern Italy, between two rivers, the Crathis (Crati) and the Sybaris (Coscile).

The city was founded in 720 BC ...

delights of diplomatic life, violence and adventure. The American edition was titled ''Escape To Adventure'', and was published a year later. All place names in this article use the spelling in the book.

Golden Road: the Soviet Union

Fresh out ofCambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, Maclean joined the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

and spent a couple of years at the Paris embassy. He loved the pleasures of life in the French capital, but eventually longed for adventure. Against the advice of his friends (and to the delight of his London bosses), he requested a posting to Moscow, which he received right away; once there, he began to learn Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

. Travelling within the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

was frowned upon by the authorities, but Maclean managed to take several trips anyway.

The Caucasus

In the spring of 1937, he took a trial trip, heading south from Moscow toBaku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world a ...

on the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia ...

. The Intourist

Intourist (russian: Интурист, a contraction of , "foreign tourist") was a Russian tour operator, headquartered in Moscow. It was founded on April 12, 1929, and served as the primary travel agency for foreign tourists in the Soviet Uni ...

official tried to dissuade him, but he found a ship to take him to Lenkoran (Lankaran

Lankaran ( az, Lənkəran, ) is a city in Azerbaijan, on the coast of the Caspian Sea, near the southern border with Iran. As of 2021, the city had a population of 89,300. It is next to, but independent of, Lankaran District. The city forms a dis ...

, Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

), where he witnessed the deportation of several hundred Turko-Tartar peasants to Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

. Stuck there for a few days, he bargained for horses with which to explore the countryside, and was arrested by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

cavalry near to the Persian border. He explained that he held diplomatic immunity

Diplomatic immunity is a principle of international law by which certain foreign government officials are recognized as having legal immunity from the jurisdiction of another country.

, but his captors could not read his Soviet diplomatic pass. Eventually, as the only person literate in Russian, Maclean "read out, with considerable expression, and such improvements as occurred to me" the contents of his pass, and was set free. He took an 1856 paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

back to Baku, and then a train on to Tiflis (Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the Capital city, capital and the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia, lying on the ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

). British troops had supported the Democratic Republic

A democratic republic is a form of government operating on principles adopted from a republic and a democracy. As a cross between two exceedingly similar systems, democratic republics may function on principles shared by both republics and democrac ...

after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and Maclean sought out the British war cemetery

A war grave is a burial place for members of the armed forces or civilians who died during military campaigns or operations.

Definition

The term "war grave" does not only apply to graves: ships sunk during wartime are often considered to b ...

, in the process discovering an English governess who had lived in the town since 1912. He caught a truck through the Caucasus mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

, via Mtzkhet (Mtskheta

Mtskheta ( ka, მცხეთა, tr ) is a city in Mtskheta-Mtianeti province of Georgia. It is one of the oldest cities in Georgia as well as one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the World. Itis located approximately north of T ...

), the former capital of Georgia but by then merely a village, to Vladikavkaz

Vladikavkaz (russian: Владикавка́з, , os, Дзæуджыхъæу, translit=Dzæwdžyqæw, ;), formerly known as Ordzhonikidze () and Dzaudzhikau (), is the capital city of the North Ossetia-Alania, Republic of North Ossetia-Alania, Ru ...

(capital of North Ossetia

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

), and then a train to Moscow.

To Samarkand

His second trip, in the autumn of the same year, took him east along theTrans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

. Although he disembarked without warning at Novosibirsk

Novosibirsk (, also ; rus, Новосиби́рск, p=nəvəsʲɪˈbʲirsk, a=ru-Новосибирск.ogg) is the largest city and administrative centre of Novosibirsk Oblast and Siberian Federal District in Russia. As of the Russian Census ...

, he acquired an NKVD escort. He travelled on the Turksib Railway south to Biisk (Biysk

Biysk ( rus, Бийск, p=bʲijsk) is a city in Altai Krai, Russia, located on the Biya River not far from its confluence with the Katun River. It is the second largest city of the krai (after Barnaul, the administrative center of the krai). Popu ...

), at the foot of the Altai Mountains

The Altai Mountains (), also spelled Altay Mountains, are a mountain range in Central Asia, Central and East Asia, where Russia, China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan converge, and where the rivers Irtysh and Ob River, Ob have their headwaters. The m ...

, and then to Altaisk and Barnaul

Barnaul ( rus, Барнау́л, p=bərnɐˈul) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative centre of Altai Krai, Russia, located at the confluence of the Barnaulka and Ob Rivers in the West Siberian Plain. As ...

. On the trains he heard the complaints of the Siberian ''kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz., a contraction of советское хозяйство, soviet ownership or ...

niks'' (workers on collective farms) and witnessed another mass movement, this time of Koreans to Central Asia. His first main destination was Alma Ata (Almaty

Almaty (; kk, Алматы; ), formerly known as Alma-Ata ( kk, Алма-Ата), is the List of most populous cities in Kazakhstan, largest city in Kazakhstan, with a population of about 2 million. It was the capital of Kazakhstan from 1929 to ...

), the capital of the Kazakh republic, which lies near to the Tien Shan

The Tian Shan,, , otk, 𐰴𐰣 𐱅𐰭𐰼𐰃, , tr, Tanrı Dağı, mn, Тэнгэр уул, , ug, تەڭرىتاغ, , , kk, Тәңіртауы / Алатау, , , ky, Теңир-Тоо / Ала-Тоо, , , uz, Tyan-Shan / Tangritog‘ ...

Mountains. He characterised it as "one of the pleasantest provincial towns in the Soviet Union" and particularly appreciated the apples for which it is famous. From there he took a truck to a hill village called Talgar

Talgar ( kk, Талғар, translit=Talğar, ; russian: Талгар) is a town in Almaty Region, southeastern Kazakhstan. It is the administrative center of Talgar District. The town is located between Almaty and Esik, 25 km from Almaty an ...

and went walking with one of his NKVD escorts; Maclean availed himself of peasant hospitality and commented on the general prosperity. He managed to hire a car and made it to Issyk-kul

Issyk-Kul (also Ysyk-Köl, ky, Ысык-Көл, lit=warm lake, translit=Ysyk-Köl, , zh, 伊塞克湖) is an endorheic lake (i.e., without outflow) in the Northern Tian Shan mountains in Eastern Kyrgyzstan. It is the seventh-deepest lake in th ...

, the lake that never freezes, but had to turn back because of the season. From Alma Ata Maclean took the train for Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of ...

, passing through villages where "nothing seemed to have changed since the time when the country was ruled over by the Emir of Bokhara

The Emirate of Bukhara ( fa, , Amārat-e Bokhārā, chg, , Bukhārā Amirligi) was a Muslims, Muslim polity in Central Asia that existed from 1785 to 1920 in what is modern-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. It occupied ...

"; men still rode bulls and women still wore veils made of black horsehair. From Tashkent, which then had a reputation for wickedness, he made the final leg to the fabled city of Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top:Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zinda, ...

. He returned to Moscow with plans for a further trip.

Maclean spent the winter working in Moscow and amusing himself at the ''dacha

A dacha ( rus, дача, p=ˈdatɕə, a=ru-dacha.ogg) is a seasonal or year-round second home, often located in the exurbs of post-Soviet countries, including Russia. A cottage (, ') or shack serving as a family's main or only home, or an outbu ...

'' (country cottage) of American friends, including Chip Bohlen. In March 1938 a show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt or innocence of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal the presentation of both the accusation and the verdict to the public so th ...

was announced, the first such public event in over a year; he attended every day of what became known as the Trial of the Twenty-One

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, ...

. The book goes into great detail, spending 40 pages on description and analysis of the trial, its prominent figures and its twists and turns.

To Chinese Turkestan

When the weather became more conducive to travel, Maclean began his third and longest trip, aiming forChinese Turkestan

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; Chinese postal romanization, formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autono ...

, immediately east of the Soviet Central Asian republics he had reached in 1937. This journey, unlike the previous two, was at the request of the British government. They wished him to investigate the conditions in Urumchi (Ürümqi

Ürümqi ( ; also spelled Ürümchi or without umlauts), formerly known as Dihua (also spelled Tihwa), is the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the far northwest of the People's Republic of China. Ürümqi developed its ...

), the capital of the province of Sinkiang (Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

), which had fallen under Soviet influence. He was commissioned to talk to the ''tupan'' (provincial governor) there about the situation of both the consul-general

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

and the British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

n traders. The first stage was retracing his steps on a five-day train journey to Alma Ata; the train ran via Orenburg

Orenburg (russian: Оренбу́рг, ), formerly known as Chkalov (1938–1957), is the administrative center of Orenburg Oblast, Russia. It lies on the Ural River, southeast of Moscow. Orenburg is also very close to the Kazakhstan-Russia bor ...

and the Aral Sea

The Aral Sea ( ; kk, Арал теңізі, Aral teñızı; uz, Орол денгизи, Orol dengizi; kaa, Арал теңизи, Aral teńizi; russian: Аральское море, Aral'skoye more) was an endorheic basin, endorheic lake lyi ...

, then parallel to the Syr Darya

The Syr Darya (, ),, , ; rus, Сырдарья́, Syrdarjja, p=sɨrdɐˈrʲja; fa, سيردريا, Sirdaryâ; tg, Сирдарё, Sirdaryo; tr, Seyhun, Siri Derya; ar, سيحون, Seyḥūn; uz, Sirdaryo, script-Latn/. historically known ...

and the mountains of Kirghizia (Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the east. ...

). From Alma Aty he travelled four hundred miles north through the Hungry Steppe to Ayaguz (Ayagoz

Ayagoz or Ayakoz ( kk, Аягөз, ''Aiagöz''), formerly Sergiopol (russian: Сергиополь), is a city of regional significance in Kazakhstan, the administrative centre of Ayagoz District, Ayagoz district of East Kazakhstan Region. Popul ...

), where "a road which had been made, and was being kept up, for a very definite purpose" led to the frontier town of Bakhti (Bakhty or Bakhtu, about 17 km from Tacheng

TachengThe official spelling according to (), as the official romanized name, also transliterated from Mongolian as Qoqak, is a county-level city (1994 est. pop. 56,400) and the administrative seat of Tacheng Prefecture, in northern Ili Kazakh A ...

, known in Maclean's time as Chuguchak). The Soviet officials were, at first, willing to assist him but the Chinese ones were not, and in the course of the negotiations that surrounded his passage, Maclean discovered that the Soviets exercised some influence over at least the consul if not the provincial government of their neighbours. He crossed the border into China, where he was refused permission to continue; he was forced to return to Alma Aty, whence he was expelled. Soon he found himself back in Moscow.

To Bokhara and Kabul

His fourth and final Soviet trip was once more to Central Asia, spurred by the desire to reach Bokhara (Bukhara

Bukhara (Uzbek language, Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara ...

, Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked cou ...

), the capital of the emirate which had been closed to Europeans until recent times. Maclean recounts how Charles Stoddart and Arthur Conolly

Arthur Conolly (2 July 1807, London – 17 June 1842, Bukhara) was a British intelligence officer, explorer and writer. He was a captain of the 6th Bengal Light Cavalry in the service of the British East India Company. He participated in many re ...

were executed there in the context of The Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

, and how Joseph Wolff

Joseph Wolff (1795 – 2 May 1862) was a Jewish Christian missionary born in Weilersbach, near Bamberg, Germany, named Wolff after his paternal grandfather. He travelled widely, and was known as "the missionary to the world". He published sev ...

, known as the Eccentric Missionary, barely escaped their fate when he came looking for them in 1845. In early October 1938 Maclean set out again, first for Ashkhabad (Ashgabat

Ashgabat or Asgabat ( tk, Aşgabat, ; fa, عشقآباد, translit='Ešqābād, formerly named Poltoratsk ( rus, Полтора́цк, p=pəltɐˈratsk) between 1919 and 1927), is the capital and the largest city of Turkmenistan. It lies ...

, capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic

The Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic (, ; russian: Туркменская Советская Социалистическая Республика, ''Turkmenskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika''), also commonly known as Turkmenistan o ...

), then through the Kara Kum (Black Desert), not breaking his journey at either Tashkent or Samarkand, but pushing on to Kagan, the nearest point on the railway to Bokhara. After trying to smuggle himself aboard a lorry transporting cotton, he ended up walking to the city, and spent several days sight-seeing "in the steps of the Eccentric Missionary" and sleeping in parks, much to the frustration of the NKVD spies who were shadowing him. He judged it an "enchanted city", with buildings that rivalled "the finest architecture of the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

". Aware of his limited time, he cut short his wanderings and took the train towards Stalinabad (Dushanbe

Dushanbe ( tg, Душанбе, ; ; russian: Душанбе) is the capital and largest city of Tajikistan. , Dushanbe had a population of 863,400 and that population was largely Tajik. Until 1929, the city was known in Russian as Dyushambe (r ...

, the capital of Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

), disembarking at Termez

Termez ( uz, Termiz/Термиз; fa, ترمذ ''Termez, Tirmiz''; ar, ترمذ ''Tirmidh''; russian: Термез; Ancient Greek: ''Tàrmita'', ''Thàrmis'', ) is the capital of Surxondaryo Region in southern Uzbekistan. Administratively, it is ...

. This town sits on the Amu Darya

The Amu Darya, tk, Amyderýa/ uz, Amudaryo// tg, Амударё, Amudaryo ps, , tr, Ceyhun / Amu Derya grc, Ὦξος, Ôxos (also called the Amu, Amo River and historically known by its Latin language, Latin name or Greek ) is a major rive ...

(the Oxus), and the other side of the river lies in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

. Maclean claimed that "very few Europeans except Soviet frontier guards have ever seen it at this or any other point of its course". After more negotiations, he managed to cross the river and thus leave the USSR, and from that point his only guide seems to have been the narrative of "the Russian Burnaby

Burnaby is a city in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia, Canada. Located in the centre of the Burrard Peninsula, it neighbours the City of Vancouver to the west, the District of North Vancouver across the confluence of the Burrard I ...

", a colonel Nikolai Ivanovich Grodekov, who rode from Samarkand to Mazar-i-Sharif

, official_name =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, pushpin_map = Afghanistan#Bactria#West Asia

, pushpin_label = Mazar-i-Sharif

, pushpin ...

and Herat

Herāt (; Persian: ) is an oasis city and the third-largest city of Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains (''Selseleh-ye Safēd ...

in 1878. The following day he and a guide set out on horseback, riding through jungle and desert, and detained on the way by dubious characters who may or may not have been brigands. (Maclean, a proficient linguist, was hamstrung on entering Afghanistan by the lack of any ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

''.) They rode past the ruins of Balkh

), named for its green-tiled ''Gonbad'' ( prs, گُنبَد, dome), in July 2001

, pushpin_map=Afghanistan#Bactria#West Asia

, pushpin_relief=yes

, pushpin_label_position=bottom

, pushpin_mapsize=300

, pushpin_map_caption=Location in Afghanistan ...

, a civilization founded by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

and destroyed by Genghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr />Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent)Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin

, ...

. After a night in Mazar, Maclean managed to get a car and driver, and progressed as rapidly as he could to Doaba, a village half-way to Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

, where he had arranged to meet the British minister (i.e., ambassador), Colonel Frazer-Tytler. Together, they returned to the capital via Bamyan

Bamyan or Bamyan Valley (); ( prs, بامیان) also spelled Bamiyan or Bamian is the capital of Bamyan Province in central Afghanistan. Its population of approximately 70,000 people makes it the largest city in Hazarajat. Bamyan is at an al ...

and its famous statues. Maclean circled back to Moscow via Peshawar

Peshawar (; ps, پېښور ; hnd, ; ; ur, ) is the sixth most populous city in Pakistan, with a population of over 2.3 million. It is situated in the north-west of the country, close to the International border with Afghanistan. It is ...

, Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

, Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

.

Orient Sand: the Western Desert Campaign

The middle section of the book details Maclean's first set of experiences inWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. He was invited to join the newly formed Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling and in 1950, it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-terro ...

(SAS), where, as part of the Western Desert Campaign, he planned and executed raids on Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

-held Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη (''Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghazi ...

, on the coast of Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

(Operation Bigamy

Operation Bigamy ''a.k.a. Operation Snowdrop'' was a raid during the Second World War by the Special Air Service in September 1942 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel David Stirling and supported by the Long Range Desert Group. The plan was ...

). When it became clear that the North African Campaign was drawing to a close towards the end of 1942 and it became too quiet for his taste, he travelled east to arrest General Fazlollah Zahedi

Fazlollah Zahedi ( fa, فضلالله زاهدی, Fazlollāh Zāhedi, pronounced ; 17 May 1892 – 2 September 1963) was an Iranian lieutenant general and statesman who replaced the Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh through a coup d'� ...

, at the time the head of the Persian armed forces in the south.

Joining up

The first challenge Maclean faced was getting into military service at all. His Foreign Office job was areserved occupation

A reserved occupation (also known as essential services) is an occupation considered important enough to a country that those serving in such occupations are exempt or forbidden from military service.

In a total war, such as the Second World War, w ...

, so he was not allowed to enlist. The only way around this was to go into politics, and on this stated ground Maclean tendered his resignation in 1941 to Alexander Cadogan

Sir Alexander Montagu George Cadogan (25 November 1884 – 9 July 1968) was a British diplomat and civil servant. He was Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs from 1938 to 1946. His long tenure of the Permanent Secretary's office makes ...

, an FO mandarin

Mandarin or The Mandarin may refer to:

Language

* Mandarin Chinese, branch of Chinese originally spoken in northern parts of the country

** Standard Chinese or Modern Standard Mandarin, the official language of China

** Taiwanese Mandarin, Stand ...

. Maclean immediately enlisted, taking a taxi from Sir Alexander's office to a nearby recruiting station, where he joined the Cameron Highlanders, his father's regiment, as a private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

. Later, his erstwhile employers discovered that his resignation had been merely a ruse or legal fiction

A legal fiction is a fact assumed or created by courts, which is then used in order to help reach a decision or to apply a legal rule. The concept is used almost exclusively in common law jurisdictions, particularly in England and Wales.

Deve ...

along the lines of taking the Chiltern Hundreds

The Chiltern Hundreds is an ancient administrative area in Buckinghamshire, England, composed of three " hundreds" and lying partially within the Chiltern Hills. "Taking the Chiltern Hundreds" refers to one of the legal fictions used to effect r ...

. Maclean was thus forced to run for office and, despite his self-confessed inexperience, was chosen as a Conservative candidate, and eventually elected MP. Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

jocularly accused him of using "the Mother of Parliaments as a public convenience"."Back to Benghazi" in ''Eastern Approaches''

Benghazi and the desert retreat

After basic training, Maclean was sent toCairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

, where David Stirling

Sir Archibald David Stirling (15 November 1915 – 4 November 1990) was a Scottish officer in the British army, a mountaineer, and the founder and creator of the Special Air Service (SAS). He saw active service during the Second World War.

...

invited him to join the newly formed Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling and in 1950, it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-terro ...

(SAS), which he did. They worked closely with the Long Range Desert Group

)Gross, O'Carroll and Chiarvetto 2009, p.20

, patron =

, motto = ''Non Vi Sed Arte'' (Latin: ''Not by Strength, but by Guile'') (unofficial)

, colours =

, colours_label ...

(LRDG), a mechanised reconnaissance unit, to travel far behind enemy lines and attack targets such as aerodromes. Maclean's first operation with the SAS, once his training was completed, was to Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη (''Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghazi ...

, Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

's second largest city, in late May 1942. He was joined on this operation by Randolph Churchill

Randolph Frederick Edward Spencer-Churchill (28 May 1911 – 6 June 1968) was an English journalist, writer, soldier, and politician. He served as Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Preston from 1940 to 1945.

The only son of British ...

, son of the prime minister. They drove from Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

via the seaport of Mersa Matruh

Mersa Matruh ( ar, مرسى مطروح, translit=Marsā Maṭrūḥ, ), also transliterated as ''Marsa Matruh'', is a port in Egypt and the capital of Matrouh Governorate. It is located west of Alexandria and east of Sallum on the main highway ...

and the inland Siwa Oasis

The Siwa Oasis ( ar, واحة سيوة, ''Wāḥat Sīwah,'' ) is an urban oasis in Egypt; between the Qattara Depression and the Great Sand Sea in the Western Desert (Egypt), Western Desert, 50 km (30 mi) east of the Libyan Egypt–Li ...

. They crossed the ancient caravan route known as the Trigh-el-Abd, which the enemy had laced with little bombs, and camped in the Gebel Akhdar, the Green Mountain just inland from the coastal plain. Once inside the occupied city, their patrol came face to face with Italian soldiers several times; Maclean, with his excellent Italian, managed to bluff his way out of all of these encounters by pretending to be a staff officer

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

. They spent two nights and a day in the city. They had hoped to sabotage ships, but both the rubber boats they had brought with them failed to inflate, so they treated the visit as a reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

mission. The drive back was uneventful, but nearing Cairo, Maclean, along with most of his party, was seriously injured in a crash and spent months out of action.

Once he had recovered, Stirling involved him in preparations for a larger SAS attack on Benghazi. They attended a dinner with Churchill, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff

The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board. Prior to 1964, the title was Chief of the Imperial G ...

General Alan Brooke

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke, (23 July 1883 – 17 June 1963), was a senior officer of the British Army. He was Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, during the Sec ...

, and General Harold Alexander, who was about to assume control of Middle East Command

Middle East Command, later Middle East Land Forces, was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to ...

, the post responsible for the overall conduct of the campaign in the North African desert. Four operations were designed to create a diversion from Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

's attempt on El Alamein

El Alamein ( ar, العلمين, translit=al-ʿAlamayn, lit=the two flags, ) is a town in the northern Matrouh Governorate of Egypt. Located on the Arab's Gulf, Mediterranean Sea, it lies west of Alexandria and northwest of Cairo. , it had ...

: attacks on Benghazi (Operation Bigamy

Operation Bigamy ''a.k.a. Operation Snowdrop'' was a raid during the Second World War by the Special Air Service in September 1942 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel David Stirling and supported by the Long Range Desert Group. The plan was ...

), Tobruk

Tobruk or Tobruck (; grc, Ἀντίπυργος, ''Antipyrgos''; la, Antipyrgus; it, Tobruch; ar, طبرق, Tubruq ''Ṭubruq''; also transliterated as ''Tobruch'' and ''Tubruk'') is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near th ...

, Barce, and the Jalo oasis

Jalo Oasis (or Jalu, or Gialo) is an oasis in Cyrenaica, Libya, located west of the Great Sand Sea and about 250 km south-east of the Gulf of Sidra. Quite large, long and up to wide, it supports a number of settlements, the largest of whic ...

. These all started out from Kufra

Kufra () is a basinBertarelli (1929), p. 514. and oasis group in the Kufra District of southeastern Cyrenaica in Libya. At the end of nineteenth century Kufra became the centre and holy place of the Senussi order. It also played a minor role in ...

, an oasis 800 miles inland. Maclean's convoy drove to the Gebel across the Sand Sea

An erg (also sand sea or dune sea, or sand sheet if it lacks dunes) is a broad, flat area of desert covered with wind-swept sand with little or no vegetative cover. The word is derived from the Arabic word ''ʿarq'' (), meaning "dune field". St ...

at its narrowest point, Zighen, and made it there undetected, although "bazaar gossip" from an Arab spy indicated that the enemy expected an imminent attack. When Maclean's group reached the outskirts of Benghazi, they were ambushed and had to retreat. Axis planes repeatedly bombed them, destroying many of the vehicles and most of their supplies. Thus began a painful limp of days and nights over the desert towards Jalo, without even knowing whether that oasis was in Allied hands. They existed on rations of "a cup of water and a tablespoon of bully beef

Bully beef (also known as corned beef in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Indonesia and other Commonwealth countries as well as the United States) is a variety of meat made from finely minced corned beef in a small amount of ge ...

a day.... We found ourselves looking forward to the evening meal with painful fixity". When they got to that oasis, they found a battle going on between the Italian defenders and the Sudan Defence Force, and despite their offers to help, they received orders from GHQ to abandon the assault. Some days later they made it back to Kufra.

The arrest of the Persian general

In September 1942 Maclean was ordered to

In September 1942 Maclean was ordered to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, where General Wilson, the new head of Persia and Iraq Command

The Persia and Iraq Command was a command of the British Army established during the Second World War in September 1942 in Baghdad. Its primary role was to secure from land and air attack the oilfields and oil installations in Persia (officially ...

, wanted his advice about starting something like the SAS in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, should that country fall to the Germans. He proceeded there to recruit volunteers, passing through many of the places he had seen in peacetime four years earlier: Kermanshah

Kermanshah ( fa, کرمانشاه, Kermânšâh ), also known as Kermashan (; romanized: Kirmaşan), is the capital of Kermanshah Province, located from Tehran in the western part of Iran. According to the 2016 census, its population is 946,68 ...

, Hamadan

Hamadan () or Hamedan ( fa, همدان, ''Hamedān'') ( Old Persian: Haŋgmetana, Ecbatana) is the capital city of Hamadan Province of Iran. At the 2019 census, its population was 783,300 in 230,775 families. The majority of people living in Ha ...

, Kazvin

Qazvin (; fa, قزوین, , also Romanized as ''Qazvīn'', ''Qazwin'', ''Kazvin'', ''Kasvin'', ''Caspin'', ''Casbin'', ''Casbeen'', or ''Ghazvin'') is the largest city and capital of the Province of Qazvin in Iran. Qazvin was a capital of the ...

, Teheran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

. He was soon diverted to a more urgent task. General Joseph Baillon, the Chief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

, and Reader Bullard

Sir Reader William Bullard (5 December 1885 – 24 May 1976) was a British diplomat and author.

Education

Reader Bullard was born in Walthamstow, the son of Charles, a dock labourer, and Mary Bullard. He was educated at the Monoux School th ...

, the minister (i.e., ambassador, as above), summoned him to Teheran. They were concerned about the influence of Fazlollah Zahedi

Fazlollah Zahedi ( fa, فضلالله زاهدی, Fazlollāh Zāhedi, pronounced ; 17 May 1892 – 2 September 1963) was an Iranian lieutenant general and statesman who replaced the Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh through a coup d'� ...

, the general in charge of the Persian forces in the Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

area, who, their intelligence told them, was stockpiling grain, liaising with German agents, and preparing an uprising. Baillon and Bullard asked Maclean to remove Zahidi alive and without creating a fuss. He devised a Trojan horse

The Trojan Horse was a wooden horse said to have been used by the Greeks during the Trojan War to enter the city of Troy and win the war. The Trojan Horse is not mentioned in Homer's ''Iliad'', with the poem ending before the war is concluded, ...

plan: he and a senior officer would call on Zahidi to pay their respects, and then arrest him "at the point of a pistol" within his walled and guarded residence. He would be whisked out in the British staff car

A staff car is a vehicle used by a senior military officer, and is part of their country's white fleet. The term is most often used in relation to the United Kingdom where they were first used in quantity during World War I, examples being the ...

, driven a waiting plane, and flown into internment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

and exile. Maclean obtained and trained a platoon of Seaforth Highlanders

The Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs, The Duke of Albany's) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, mainly associated with large areas of the northern Highlands of Scotland. The regiment existed from 1881 to 1961, and saw servic ...

to cover his retreat, and the plan went like clockwork. (Zahidi spent the rest of the war in British Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 i ...

; five years later he was back in charge of the military of southern Persia, by 1953 he was prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

.)

By the end of the year, the war had developed in such a way that the new SAS detachment would not be needed in Persia. General Wilson was being transferred to Middle East Command

Middle East Command, later Middle East Land Forces, was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to ...

, and Maclean extracted a promise that the newly trained troops would go with him, as their style of commando raids were ideal for southern and eastern Europe. Frustrated by the abandoning of plans for an assault on Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

, Maclean went to see Reginald Leeper

Sir Reginald "Rex" Wilding Allen Leeper (25 March 1888 – 2 February 1968) was a British civil servant and diplomat. He was the founder of the British Council.

Born in Sydney, Australia, Leeper was educated at Melbourne Grammar School, Melb ...

, "an old friend from Foreign Office days, and now His Majesty's Ambassador to the Greek Government then in exile in Cairo". Leeper put in a word for him, and very soon Maclean was told to go to London to get his instructions directly from the prime minister. Churchill told him to parachute into Jugoslavia (now spelled Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

) as head of a military mission accredited to Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

(a shadowy figure at that point) or whoever was in charge of the Partisans, the Communist-led resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objective ...

. Mihajlovic's royalist Cetniks (now spelled Chetniks), which the Allies had been supporting, did not appear to be fighting the Germans very hard, and indeed were said to be collaborating with the enemy. Maclean famously paraphrased Churchill: "My task was simply to help find out who was killing the most Germans and suggest means by which we could help them to kill more." The prime minister saw Maclean as "a daring Ambassador-leader to these hardy and hunted guerillas".

Balkan War: With Tito in Yugoslavia

The final and longest section of the book covers Maclean's time in and around Yugoslavia, from the late summer of 1943 to the formation of the united government in March 1945. The Yugoslav front, also known as the Yugoslav People's Liberation War, had become important to the Allies by 1943, although the Partisans had been fighting for two years without any help. He lived closely with Tito and his troops and had the ear of Churchill, and as such his recommendations shaped the Allies' policy towards Yugoslavia.

The final and longest section of the book covers Maclean's time in and around Yugoslavia, from the late summer of 1943 to the formation of the united government in March 1945. The Yugoslav front, also known as the Yugoslav People's Liberation War, had become important to the Allies by 1943, although the Partisans had been fighting for two years without any help. He lived closely with Tito and his troops and had the ear of Churchill, and as such his recommendations shaped the Allies' policy towards Yugoslavia.

The list of characters

In the late summer of 1943, Maclean parachuted intoBosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and He ...

with Vivian Street and Slim Farish (whom he called his British and American Chiefs of Staff, respectively) and Sergeant Duncan, his bodyguard. They were attached to Tito's headquarters, then in the ruined castle of Jajce

Jajce (Јајце) is a town and municipality located in the Central Bosnia Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. According to the 2013 census, the town has a population of 7,172 inhabitants, with ...

. Here and elsewhere, Maclean lived in proximity to the Partisan leader for a year and a half, on and off. Maclean gives much of this section of the book to his personal assessment of the Partisan position and of Tito as a man and as a leader. Their talks, in German and Russian (while Maclean learned Serbo-Croat), were wide-ranging, and from them Maclean gained hope that a future Communist Yugoslavia might not be the fear-wracked place the USSR was. The Partisans were extremely proud of their movement, dedicated to it, and prepared to live a life of austerity in its cause. All of this won his admiration.

Some of the characters close to Tito whom Maclean met in his first months in Bosnia were Vlatko Velebit, an urbane young man about town, who later went with Maclean to Allied HQ as a liaison officer; Father Vlado (Vlada Zečević

Vladimir "Vlada" Zečević ( Serbian- Cyrillic: Владимир Влада Зечевић; 21 March 1903 ( OS), in Loznica – 26 October 1970, in Belgrade) was a Serbian Orthodox priest and later a member of the League of Communists of Yugos ...

), a Serbian Orthodox priest, "raconteur and trencherman"; Arso Jovanović

Arsenije "Arso" Jovanović ( sr-cyr, Арсо Јовановић; 24 March 1907 – 12 August 1948) was a Yugoslav partisan general and one of the country's foremost military commanders during World War II in Yugoslavia.

Educated through the ...

, the Chief of Staff; Edo Kardelj, the Marxist theoretician who ended up vice-premier; Aleksandar Ranković

Aleksandar Ranković ( nom de guerre Marko; sr-Cyrl, Александар Ранковић Лека; 28 November 1909 – 19 August 1983) was a Yugoslav communist politician, considered to be the third most powerful man in Yugoslavia after Jo ...

, a professional revolutionary and Party organiser; Milovan Đilas

Milovan Djilas (; , ; 12 June 1911 – 30 April 1995) was a Yugoslav communist politician, theorist and author. He was a key figure in the Partisan movement during World War II, as well as in the post-war government. A self-identified democrat ...

(Dzilas), who became vice-president; Moša Pijade

Moša Pijade ( sr-Cyrl, Мoшa Пијаде; he, משה פיאדה; alternate English transliteration Moshe Piade; 4 January 1890 – 15 March 1957), nicknamed Čiča Janko (, lit. "Old Man Janko") was a Serbian and Yugoslav communist of J ...

, one of the highest-ranking Jews; and a young woman named Olga whose father Momčilo Ninčić

Momčilo Ninčić ( – 23 December 1949) was a Serbian and Yugoslav politician and economist, president of the League of Nations from 1926 to 1927.

Early life and education

Momčilo Ninčić was born in Jagodina on to Aaron and Paula Nin� ...

had been a minister in the Royalist government and who spoke English like a debutante.

Other Yugoslavs of note whom he met later included Koča Popović

Konstantin "Koča" Popović ( sr-cyrl, Константин "Коча" Поповић; 14 March 1908 – 20 October 1992) was a Yugoslav politician and communist volunteer in the Spanish Civil War, 1937–1939 and Divisional Commander of the Fir ...

, later Chief of the General Staff of Yugoslav People's Army, whom Maclean judged "one of the outstanding figures of the Partisan Movement"; Ivo Lola Ribar

Ivan Ribar (23 April 1916 – 27 November 1943), known as Ivo Lola or Ivo Lolo, was a Yugoslav communist politician and military leader of Croatian descent. In the 1930s, he became one of the closest associates of Josip Broz Tito, leader of the ...

, son of Dr Ivan Ribar

Ivan Ribar (; 21 January 1881 – 2 February 1968) was a Croatian politician who served in several governments of various forms in Yugoslavia. Ideologically a Pan-Slavist and communist, he was a prominent member of the Yugoslav Partisans, who r ...

, who seemed destined for great things; Miloje Milojević

Miloje Milojević (Serbian Cyrillic: Милоје Милојевић; 27 October 1884, Belgrade – 16 June 1946, Belgrade) was a Serbian composer, musicologist, music critic, folklorist, music pedagogue, and music promoter.

Biography ...

; Slavko Rodić

Slavko Rodić ( sr, Славко Родић; Sredice near Ključ, 7 July 1914 - Belgrade, 29 April 1949), was a Yugoslav partisan, general of Yugoslav People's Army and People's Hero of Yugoslavia.

Prior to April War, Rodić worked as sur ...

; Sreten Žujović

Sreten Žujović ( sr-cyr, Сретен Жујовић; 24 June 1899 – 11 June 1976) was a Serbian and Yugoslav politician and veteran of World War I and long-time communist.

Biography

He was born into a wealthy family, and was a Serb by nation ...

(Crni the Black).

Officers and soldiers under Maclean's command included Peter Moore of the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

; Mike Parker, Deputy Assistant Quartermaster general; Gordon Alston; John Henniker-Major, a career diplomat; Donald Knight, and Robin Whetherly.

Maclean arranged for an Allied officer, under his command, to be attached to each of the main Partisan bases, bringing with him a radio transmitting set. Maclean was not in fact the first Allied officer in Yugoslavia, but the few who had been dropped before him had not been able to get much of their information out. Maclean made contact with Bill Deakin, an Oxford history don who had served as a research assistant to Churchill; Anthony Hunter, a Scots Fusilier, and Major William Jones, an enthusiastic but unorthodox one-eyed Canadian.

First journey across Bosnia and Dalmatia

Maclean saw his task as arranging supplies and air support for the Partisan fight, to tie up the Axis forces for as long as possible. TheRoyal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

was reluctant to risk landing on what they saw as an amateur airstrip at Glamoj (Glamoč

Glamoč ( sr-cyrl, Гламоч) is a town and municipality located in Canton 10 of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is situated in southwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina, at the foothills of Staretin ...

), although Slim Farish was in fact an airfield designer, and night air drops were sporadic. The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

was approached, and they offered to bring supplies to an outlying island off the Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

n coast. Maclean and a couple of companions set off on foot for Korčula

Korčula (, it, Curzola) is a Croatian island in the Adriatic Sea. It has an area of , is long and on average wide, and lies just off the Dalmatian coast. Its 15,522 inhabitants (2011) make it the second most populous Adriatic island after K ...

, being passed from guerilla group to guerilla group. They passed through battle-scarred villages and towns that had changed hands many times, some so recently that corpses still lay on the ground: Bugojno

Bugojno ( sr-cyrl, Бугојно) is a town and municipality located in Central Bosnia Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is situated on river Vrbas, to the northwest from Sarajevo. Acco ...

and Livno

Livno ( sr-cyrl, Ливно, ) is a city and the administrative center of Canton 10 of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is situated on the river Bistrica in the southeastern edge of the Livno Field ...

and Aržano

Aržano is a small village in Zagora, Croatia, situated near the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina at an altitude of 650 m. The population is 478 (2011 census). There is an influx of descendants that arrive during the holiday periods, mainly fro ...

. Once, they were billeted with a landlady whose sympathies clearly did not lie with the Partisans; she would not sell them food, but there was no question of simply commandeering it. Eventually, after an all-night march across noisy stony ground, dodging German patrols as they crossed a major road, the little group reached Zadvarje

Zadvarje is a village and a municipality in the Split-Dalmatia County, Croatia. It has a population of 289 (2011 census), 99.3% of which are Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian a ...

, where they were greeted with astonishment as creatures from another world "as indeed in a sense we were". After a few hours' sleep, they continued over the final range of hills to the coast, and down to Baška Voda

Baška Voda () is a municipality in Croatia in the Split-Dalmatia County. It has a population of 2,775 (2011 census), 96.2% of which are Croats. It is located on the Adriatic coastline of Dalmatia 10 km northwest of Makarska.

Climate

Ba ...

, where a fishing boat took them circuitously to Korčula. There, all seemed in order for a Navy supply drop, but the wireless set developed problems. Maclean was on the point of returning to Jajce when the motor launch

A Motor Launch (ML) is a small military vessel in Royal Navy service. It was designed for harbour defence and submarine chasing or for armed high-speed air-sea rescue. Some vessels for water police service are also known as motor launches.

...

arrived, with a crew that included Sandy Glen

Sir Alexander Richard Glen KBE DSC (18 April 1912 – 6 March 2004) was a Scottish explorer of the Arctic, and wartime intelligence officer. He later invested in the shipping industry, employed Tom Gullick who was a pioneer of package holidays, ...

(also, like Maclean, thought to be one of the inspirations for James Bond

A number of real-life inspirations have been suggested for James Bond (literary character), James Bond, the fictional character created in 1953 by British author, journalist and British Naval Intelligence, Naval Intelligence officer Ian Fleming (1 ...

) and David Satow. By this point the enemy were closing in to take the remaining access points to the coast, which would throttle the Partisan supply route before it had even begun. He sent top priority requests, asking for air and sea support from Allied bases in Italy, and these took effect. Maclean decided he needed to discuss matters with Tito and then with Allied superiors in Cairo to argue for more resources to push the project forward, and accordingly made his way back to Partisan HQ in Jajce. He returned to the islands, first on Hvar

Hvar (; Chakavian: ''Hvor'' or ''For'', el, Φάρος, Pharos, la, Pharia, it, Lesina) is a Croatian island in the Adriatic Sea, located off the Dalmatian coast, lying between the islands of Brač, Vis and Korčula. Approximately long,

wi ...

and then on Vis, to wait for the response to his strongly worded signals. On Vis he discovered an overgrown British war cemetery dating from a naval victory over the French in 1811.

Gaining support

In Cairo Maclean dined with Alexander Cadogan, his FO superior, and the next day reported toAnthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

, the Foreign Secretary. He stated his conclusions straightforwardly: that the Partisans were important militarily and politically and would influence the future of Yugoslavia whether the Allies helped them or not; their impact on the Germans could be greatly increased by Allied support; they were Communist and oriented towards the USSR. He says that his report created "something of a stir". He was sent back to collect two Yugoslav liaison officers who had not been allowed to come out with him on the first Navy pick-up. From Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy a ...

on the Italian Adriatic coast

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

, now a centre of operations for the Tactical Air Force

The term Tactical Air Force was used by the air forces of the British Commonwealth during the later stages of World War II, for formations of more than one fighter group. A tactical air force was intended to achieve air supremacy and perform grou ...

, he saw that this would prove difficult, as the German offensive had captured the whole Dalmatian coast. Fortunately, he had asked Air Marshal Sholto Douglas

Sholto Douglas was the mythical progenitor of Clan Douglas, a powerful and warlike family in medieval Scotland.

A mythical battle took place: "in 767, between King '' Solvathius'' rightful king of Scotland and a pretender ''Donald Bane''. The vic ...

to assign him a liaison officer

A Liaison officer is a person who liaises between two or more organizations to communicate and coordinate their activities on a matter of mutual concern. Generally, liaison officers are used for achieving the best utilization of resources, or empl ...

, and Wing Commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr in the RAF, the IAF, and the PAF, WGCDR in the RNZAF and RAAF, formerly sometimes W/C in all services) is a senior commissioned rank in the British Royal Air Force and air forces of many countries which have historical ...

John B. Selby proved a godsend. Together they obtained the use of a Baltimore bomber and an escort of Lightnings. Twice they set out from Italy on a sunny day and twice the clouds blocked them from the Bosnian hills. On the third day the fighters were unavailable so the bomber set out alone, but again the weather made it impossible to land. On their return to Italy, they received a signal that the Partisans had captured a small German plane that they proposed to use. As they were loading up the plane, an enemy aircraft, alerted by a traitor, bombed the landing strip at Glamoc, killing Whetherly, Knight, and Ribar, and wounding Milojevic. This event, at the end of November, proved a spur to getting the mission higher priority, and soon Maclean got a large Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota, ...

and half a squadron of Lightnings to complete the landing operation. Milojevic and Velebit accompanied Maclean to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, where the Yugoslavs decompressed for a few days, while Maclean sought out the prime minister.

Churchill received him in trademark fashion: in bed, wearing an embroidered dressing gown, smoking a cigar. He, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, and Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

had discussed the matter of Yugoslavia at a recent conference in Teheran, and had decided to give all possible support to the Partisans. This was the turning point. The Chetniks were given a task (a bridge to blow up) and a deadline, to show whether they could still be effective allies; they failed this test and supplies were re-directed from them to the Partisans. The British government was left with the tricky political and moral problem of King Peter and his royalist government in exile. But the main issues were air supplies and air support, and to help co-ordinate this, Maclean's mission was expanded. Some of the new officers included Andrew Maxwell of the Scots Guards, John Clarke of the 2nd Scots Guards, Geoffrey Kup, a gunnery expert, Hilary King, a signals officer, Johnny Tregida, and, for a time, Randolph Churchill. Some of these were SAS or otherwise known from the Western Desert Campaign the previous year.

Marshal of Yugoslavia

Maclean returned to the islands and settled on Vis as being the best site for an airstrip and a naval base. He then needed to garrison it. He discussed the matter with General Alexander and his Chief of Staff General John Harding, who seemed to think it might be possible, and who gave him a lift toMarrakech

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

to put the matter to the prime minister. Churchill assured him on the point of troops, and wrote a personal letter to Tito which he commissioned Maclean to deliver. Maclean parachuted into Bosnia again, thinking it no longer an unknown, as it had been only six months before. Tito, since the end of November Marshal of Yugoslavia

Marshal of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Maršal Jugoslavije, Маршал Југославије; sl, Maršal Jugoslavije; mk, Маршал на Југославија, Maršal na Jugoslavija) was the Highest military ranks, hig ...

, was delighted with the recognition from Churchill, as from one statesman to another.

The Partisan headquarters moved to the village of Drvar

Drvar (, ) is a town and municipality located in Canton 10 of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The 2013 census registered the municipality as having a population of 7,036. It is situated in western Bos ...

, where Tito took up residence in a cave with a waterfall. Maclean spent months there with him, "talking, eating, and above all, arguing". He and Tito agreed a system of allocating the air drop supplies around the country, although there was some friction from officers wanting a bigger share. Air drops became much more frequent, as did air support for Partisan operations. At this point all support for the Cetniks was withdrawn, a fact Churchill announced in the House of Commons. Maclean decided to go to Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

to see for himself what this stronghold of Cetniks held for the Partisans. In early April, before this could be arranged, he was ordered to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

for further discussions. (A stop-over in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

meant a specially arranged radio phone call with Churchill. Maclean, who hated telephone conversations, managed to wring amusement from the mix-ups of codes and scrambling. Churchill's son was referred to as Pippin

Pippin or Pepin may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Pippin (comics), ''Pippin'' (comics), a children's comic produced from 1966 to 1986

* Pippin (musical), ''Pippin'' (musical), a Broadway musical by Stephen Schwartz loosely based on the life ...

.)

They arrived in England to find "the whole of the southern counties ereone immense armed camp". Despite the tension over the anticipated invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

, the press and officials were eager to hear the Yugoslav story, and Maclean and Velebit had a busy time; even U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

wanted to meet them. At Chequers

Chequers ( ), or Chequers Court, is the country house of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. A 16th-century manor house in origin, it is located near the village of Ellesborough, halfway between Princes Risborough and Wendover in Bucking ...

Maclean participated in attempts to build a possible compromise between the Royalist government in exile and the Partisans. As Maclean was preparing to go back to Bari and Bosnia, he received news that the enemy had made a fierce attack on Partisan headquarters at Drvar, later known as the Knight's Move. "It was the kind of communication that took your breath away." When he got the full story from Vivian Street, he heard how the German bombers had made a full and thorough attack, and, after Tito and the Partisans escaped, revenged themselves on the civilians, massacring almost everyone, men, women, and children. In the week that followed the attack on Drvar, Allied planes flew more than a thousand sorties in support of the Partisans. Tito, harassed and harried through the woods, reached the decision that he needed to leave and establish his headquarters in a place of security. Accordingly, he asked Vivian Street to arrange for the Allies to evacuate him and his staff, which they did. Maclean, on his way back from London, caught up with the Marshal at Bari, and found him proposing to establish his base on Vis. The Royal Navy took him across in fine style, with a memorable wardroom dinner, at which Tito recited, in English, "The Owl and the Pussycat

"The Owl and the Pussy-cat" is a nonsense poem by Edward Lear, first published in 1870 in the American magazine '' Our Young Folks: an Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls'' and again the following year in Lear's own book ''Nonsense Songs, S ...

".

Negotiating the future of Yugoslavia

Vis had been transformed in the intervening months, becoming a substantial base for aircraft, commandos, and navy boats "engaged in piratical activities against enemy shipping up and down the whole length of the Jugoslav coastline fromIstria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

to Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

". Meanwhile, other fronts of the war were progressing rapidly, and the Germans were hard-pressed. It was necessary to discuss the future shape of Yugoslavia at the highest possible level, and so Maclean was instructed to invite Tito and his entourage to Caserta