An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

's

lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust (geology), crust and the portion of the upper mantle (geology), mantle that behaves elastically on time sca ...

that creates

seismic wave

A seismic wave is a wave of acoustic energy that travels through the Earth. It can result from an earthquake, volcanic eruption, magma movement, a large landslide, and a large man-made explosion that produces low-frequency acoustic energy. S ...

s. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from those that are so weak that they cannot be felt, to those violent enough to propel objects and people into the air, damage critical infrastructure, and wreak destruction across entire cities. The seismic activity of an area is the frequency, type, and size of earthquakes experienced over a particular time period. The

seismicity

Seismicity is a measure encompassing earthquake occurrences, mechanisms, and magnitude at a given geographical location. As such, it summarizes a region's seismic activity. The term was coined by Beno Gutenberg and Charles Francis Richter in 19 ...

at a particular location in the Earth is the average rate of seismic energy release per unit volume. The word ''tremor'' is also used for

non-earthquake seismic rumbling.

At the Earth's surface, earthquakes manifest themselves by shaking and displacing or disrupting the ground. When the

epicenter

The epicenter, epicentre () or epicentrum in seismology is the point on the Earth's surface directly above a hypocenter or focus, the point where an earthquake or an underground explosion originates.

Surface damage

Before the instrumental pe ...

of a large earthquake is located offshore, the seabed may be displaced sufficiently to cause a

tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater explo ...

. Earthquakes can also trigger

landslide

Landslides, also known as landslips, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, deep-seated grade (slope), slope failures, mudflows, and debris flows. Landslides occur in a variety of ...

s.

In its most general sense, the word ''earthquake'' is used to describe any seismic event—whether natural or caused by humans—that generates seismic waves. Earthquakes are caused mostly by rupture of geological

faults but also by other events such as volcanic activity, landslides, mine blasts, and

nuclear tests

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

. An earthquake's point of initial rupture is called its

hypocenter

In seismology, a hypocenter or hypocentre () is the point of origin of an earthquake or a subsurface nuclear explosion. A synonym is the focus of an earthquake.

Earthquakes

An earthquake's hypocenter is the position where the strain energy s ...

or focus. The

epicenter

The epicenter, epicentre () or epicentrum in seismology is the point on the Earth's surface directly above a hypocenter or focus, the point where an earthquake or an underground explosion originates.

Surface damage

Before the instrumental pe ...

is the point at ground level directly above the hypocenter.

Naturally occurring earthquakes

Tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents k ...

earthquakes occur anywhere in the earth where there is sufficient stored elastic strain energy to drive fracture propagation along a

fault plane

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectonic ...

. The sides of a fault move past each other smoothly and

aseismically only if there are no irregularities or

asperities

In materials science, asperity, defined as "unevenness of surface, roughness, ruggedness" (from the Latin ''asper''—"rough"), has implications (for example) in physics and seismology. Smooth surfaces, even those polished to a mirror finish, ar ...

along the fault surface that increase the frictional resistance. Most fault surfaces do have such asperities, which leads to a form of

stick-slip behavior. Once the fault has locked, continued relative motion between the plates leads to increasing stress and, therefore, stored strain energy in the volume around the fault surface. This continues until the stress has risen sufficiently to break through the asperity, suddenly allowing sliding over the locked portion of the fault, releasing the

stored energy.

This energy is released as a combination of radiated elastic

strain

Strain may refer to:

Science and technology

* Strain (biology), variants of plants, viruses or bacteria; or an inbred animal used for experimental purposes

* Strain (chemistry), a chemical stress of a molecule

* Strain (injury), an injury to a mu ...

seismic waves

A seismic wave is a wave of acoustic energy that travels through the Earth. It can result from an earthquake, volcanic eruption, magma movement, a large landslide, and a large man-made explosion that produces low-frequency acoustic energy. S ...

, frictional heating of the fault surface, and cracking of the rock, thus causing an earthquake. This process of gradual build-up of strain and stress punctuated by occasional sudden earthquake failure is referred to as the

elastic-rebound theory

__NOTOC__

In geology, the elastic-rebound theory is an explanation for how energy is released during an earthquake.

As the Earth's crust deforms, the rocks which span the opposing sides of a fault are subjected to shear stress. Slowly they def ...

. It is estimated that only 10 percent or less of an earthquake's total energy is radiated as seismic energy. Most of the earthquake's energy is used to power the earthquake

fracture

Fracture is the separation of an object or material into two or more pieces under the action of stress. The fracture of a solid usually occurs due to the development of certain displacement discontinuity surfaces within the solid. If a displa ...

growth or is converted into heat generated by friction. Therefore, earthquakes lower the Earth's available

elastic potential energy

Elastic energy is the mechanical potential energy stored in the configuration of a material or physical system as it is subjected to elastic deformation by work performed upon it. Elastic energy occurs when objects are impermanently compressed, s ...

and raise its temperature, though these changes are negligible compared to the conductive and convective flow of heat out from the

Earth's deep interior.

Earthquake fault types

There are three main types of fault, all of which may cause an

interplate earthquake

An interplate earthquake is an earthquake that occurs at the boundary between two tectonic plates. Earthquakes of this type account for more than 90 percent of the total seismic energy released around the world. If one plate is trying to move past ...

: normal, reverse (thrust), and strike-slip. Normal and reverse faulting are examples of dip-slip, where the displacement along the fault is in the direction of

dip and where movement on them involves a vertical component. Many earthquakes are caused by movement on faults that have components of both dip-slip and strike-slip; this is known as oblique slip. The topmost, brittle part of the Earth's crust, and the cool slabs of the tectonic plates that are descending into the hot mantle, are the only parts of our planet that can store elastic energy and release it in fault ruptures. Rocks hotter than about flow in response to stress; they do not rupture in earthquakes. The maximum observed lengths of ruptures and mapped faults (which may break in a single rupture) are approximately . Examples are the earthquakes in

Alaska (1957),

Chile (1960), and

Sumatra (2004), all in subduction zones. The longest earthquake ruptures on strike-slip faults, like the

San Andreas Fault

The San Andreas Fault is a continental transform fault that extends roughly through California. It forms the tectonics, tectonic boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, and its motion is Fault (geology)#Strike-slip fau ...

(

1857

Events January–March

* January 1 – The biggest Estonian newspaper, ''Postimees'', is established by Johann Voldemar Jannsen.

* January 7 – The partly French-owned London General Omnibus Company begins operating.

* Janua ...

,

1906

Events

January–February

* January 12 – Persian Constitutional Revolution: A nationalistic coalition of merchants, religious leaders and intellectuals in Persia forces the shah Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar to grant a constitution, ...

), the

North Anatolian Fault

The North Anatolian Fault (NAF) ( tr, Kuzey Anadolu Fay Hattı) is an active right-lateral strike-slip fault in northern Anatolia, and is the transform boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the Anatolian Plate. The fault extends westward fro ...

in Turkey (

1939

This year also marks the start of the Second World War, the largest and deadliest conflict in human history.

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* January 1

** Third Reich

*** Jews are forbidden to ...

), and the

Denali Fault

The Denali Fault is a major intracontinental dextral (right lateral) strike-slip fault in western North America, extending from northwestern British Columbia, Canada to the central region of the U.S. state of Alaska.

Location

The Denali Fault i ...

in Alaska (

2002

File:2002 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The 2002 Winter Olympics are held in Salt Lake City; Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother and her daughter Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon die; East Timor gains East Timor independence, indepe ...

), are about half to one third as long as the lengths along subducting plate margins, and those along normal faults are even shorter.

Normal faults

Normal faults occur mainly in areas where the crust is being

extended

Extension, extend or extended may refer to:

Mathematics

Logic or set theory

* Axiom of extensionality

* Extensible cardinal

* Extension (model theory)

* Extension (predicate logic), the set of tuples of values that satisfy the predicate

* Exte ...

such as a

divergent boundary

In plate tectonics, a divergent boundary or divergent plate boundary (also known as a constructive boundary or an extensional boundary) is a linear feature that exists between two tectonic plates that are moving away from each other. Divergent b ...

. Earthquakes associated with normal faults are generally less than magnitude 7. Maximum magnitudes along many normal faults are even more limited because many of them are located along spreading centers, as in Iceland, where the thickness of the brittle layer is only about .

Reverse faults

Reverse faults occur in areas where the crust is being

shortened such as at a convergent boundary. Reverse faults, particularly those along

convergent plate boundaries

A convergent boundary (also known as a destructive boundary) is an area on Earth where two or more lithospheric plates collide. One plate eventually slides beneath the other, a process known as subduction. The subduction zone can be defined by a ...

, are associated with the most powerful earthquakes,

megathrust earthquake

Megathrust earthquakes occur at convergent plate boundaries, where one tectonic plate is forced underneath another. The earthquakes are caused by slip along the thrust fault that forms the contact between the two plates. These interplate earthqua ...

s, including almost all of those of magnitude 8 or more. Megathrust earthquakes are responsible for about 90% of the total seismic moment released worldwide.

Strike-slip faults

Strike-slip fault

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectonic ...

s are steep structures where the two sides of the fault slip horizontally past each other; transform boundaries are a particular type of strike-slip fault. Strike-slip faults, particularly continental

transforms

Transform may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*Transform (scratch), a type of scratch used by turntablists

* ''Transform'' (Alva Noto album), 2001

* ''Transform'' (Howard Jones album) or the title song, 2019

* ''Transform'' (Powerman 5000 album) ...

, can produce major earthquakes up to about magnitude 8. Strike-slip faults tend to be oriented near vertically, resulting in an approximate width of within the brittle crust. Thus, earthquakes with magnitudes much larger than 8 are not possible.

In addition, there exists a hierarchy of stress levels in the three fault types. Thrust faults are generated by the highest, strike-slip by intermediate, and normal faults by the lowest stress levels. This can easily be understood by considering the direction of the greatest principal stress, the direction of the force that "pushes" the rock mass during the faulting. In the case of normal faults, the rock mass is pushed down in a vertical direction, thus the pushing force (''greatest'' principal stress) equals the weight of the rock mass itself. In the case of thrusting, the rock mass "escapes" in the direction of the least principal stress, namely upward, lifting the rock mass, and thus, the overburden equals the ''least'' principal stress. Strike-slip faulting is intermediate between the other two types described above. This difference in stress regime in the three faulting environments can contribute to differences in stress drop during faulting, which contributes to differences in the radiated energy, regardless of fault dimensions.

Energy released

For every unit increase in magnitude, there is a roughly thirtyfold increase in the energy released. For instance, an earthquake of magnitude 6.0 releases approximately 32 times more energy than a 5.0 magnitude earthquake and a 7.0 magnitude earthquake releases 1,000 times more energy than a 5.0 magnitude earthquake. An 8.6 magnitude earthquake releases the same amount of energy as 10,000 atomic bombs of the size used in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

This is so because the energy released in an earthquake, and thus its magnitude, is proportional to the area of the fault that ruptures and the stress drop. Therefore, the longer the length and the wider the width of the faulted area, the larger the resulting magnitude. The most important parameter controlling the maximum earthquake magnitude on a fault, however, is not the maximum available length, but the available width because the latter varies by a factor of 20. Along converging plate margins, the dip angle of the rupture plane is very shallow, typically about 10 degrees. Thus, the width of the plane within the top brittle crust of the Earth can become (

Japan, 2011;

Alaska, 1964), making the most powerful earthquakes possible.

Shallow-focus and deep-focus earthquakes

The majority of tectonic earthquakes originate in the ring of fire at depths not exceeding tens of kilometers. Earthquakes occurring at a depth of less than are classified as "shallow-focus" earthquakes, while those with a focal-depth between are commonly termed "mid-focus" or "intermediate-depth" earthquakes. In

subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

zones, where older and colder

oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafic cumu ...

descends beneath another tectonic plate,

deep-focus earthquake A deep-focus earthquake in seismology (also called a plutonic earthquake) is an earthquake with a hypocenter depth exceeding 300 km. They occur almost exclusively at convergent boundary, convergent boundaries in association with subducted ocean ...

s may occur at much greater depths (ranging from ). These seismically active areas of subduction are known as

Wadati–Benioff zone

A Wadati–Benioff zone (also Benioff–Wadati zone or Benioff zone or Benioff seismic zone) is a planar zone of seismicity corresponding with the down-going slab in a subduction zone. Differential motion along the zone produces numerous earthqu ...

s. Deep-focus earthquakes occur at a depth where the subducted

lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust (geology), crust and the portion of the upper mantle (geology), mantle that behaves elastically on time sca ...

should no longer be brittle, due to the high temperature and pressure. A possible mechanism for the generation of deep-focus earthquakes is faulting caused by

olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle, it is a common mineral in Earth's subsurface, but weathers quickl ...

undergoing a

phase transition

In chemistry, thermodynamics, and other related fields, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic states of ...

into a

spinel

Spinel () is the magnesium/aluminium member of the larger spinel group of minerals. It has the formula in the cubic crystal system. Its name comes from the Latin word , which means ''spine'' in reference to its pointed crystals.

Properties

S ...

structure.

Earthquakes and volcanic activity

Earthquakes often occur in volcanic regions and are caused there, both by

tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents k ...

faults and the movement of

magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

in

volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates are ...

es. Such earthquakes can serve as an early warning of volcanic eruptions, as during the

1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens

On March 27, 1980, a series of volcanic explosions and pyroclastic flows began at Mount St. Helens in Skamania County, Washington, United States. A series of phreatic blasts occurred from the summit and escalated until a major explosive eru ...

. Earthquake swarms can serve as markers for the location of the flowing magma throughout the volcanoes. These swarms can be recorded by

seismometers

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground noises and shaking such as caused by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The output ...

and

tiltmeter

A tiltmeter is a sensitive inclinometer designed to measure very small changes from the vertical level, either on the ground or in structures. Tiltmeters are used extensively for monitoring volcanoes, the response of dams to filling, the small m ...

s (a device that measures ground slope) and used as sensors to predict imminent or upcoming eruptions.

Rupture dynamics

A tectonic earthquake begins as an area of initial slip on the fault surface that forms the focus. Once the rupture has initiated, it begins to propagate away from the focus, spreading out along the fault surface. Lateral propagation will continue until either the rupture reaches a barrier, such as the end of a fault segment, or a region on the fault where there is insufficient stress to allow continued rupture. For larger earthquakes, the depth extent of rupture will be constrained downwards by the

brittle-ductile transition zone and upwards by the ground surface. The mechanics of this process are poorly understood, because it is difficult either to recreate such rapid movements in a laboratory or to record seismic waves close to a nucleation zone due to strong ground motion.

In most cases the rupture speed approaches, but does not exceed, the

shear wave

__NOTOC__

In seismology and other areas involving elastic waves, S waves, secondary waves, or shear waves (sometimes called elastic S waves) are a type of elastic wave and are one of the two main types of elastic body waves, so named because th ...

(S-wave) velocity of the surrounding rock. There are a few exceptions to this:

Supershear earthquakes

Supershear earthquake

In seismology, a supershear earthquake is an earthquake in which the propagation of the rupture along the fault surface occurs at speeds in excess of the seismic shear wave (S-wave) velocity. This causes an effect analogous to a sonic boom.

Rup ...

ruptures are known to have propagated at speeds greater than the S-wave velocity. These have so far all been observed during large strike-slip events. The unusually wide zone of damage caused by the

2001 Kunlun earthquake

The 2001 Kunlun earthquake also known as the 2001 Kokoxili earthquake, occurred on 14 November 2001 at 09:26 UTC (17:26 local time), with an epicenter near Kokoxili, close to the border between Qinghai and Xinjiang in a remote mountainous regi ...

has been attributed to the effects of the

sonic boom

A sonic boom is a sound associated with shock waves created when an object travels through the air faster than the speed of sound. Sonic booms generate enormous amounts of sound energy, sounding similar to an explosion or a thunderclap to t ...

developed in such earthquakes.

Slow earthquakes

Slow earthquake

A slow earthquake is a discontinuous, earthquake-like event that releases energy over a period of hours to months, rather than the seconds to minutes characteristic of a typical earthquake. First detected using long term strain measurements, most ...

ruptures travel at unusually low velocities. A particularly dangerous form of slow earthquake is the

tsunami earthquake

In seismology, a tsunami earthquake is an earthquake which triggers a tsunami of significantly greater magnitude, as measured by shorter-period seismic waves. The term was introduced by Japanese seismologist Hiroo Kanamori in 1972. Such events a ...

, observed where the relatively low felt intensities, caused by the slow propagation speed of some great earthquakes, fail to alert the population of the neighboring coast, as in the

1896 Sanriku earthquake

The was one of the most destructive seismic events in Japanese history. The 8.5 Moment magnitude scale, magnitude earthquake occurred at 19:32 (local time) on June 15, 1896, approximately off the coast of Iwate Prefecture, Honshu. It resulted i ...

.

Co-seismic overpressuring and effect of pore pressure

During an earthquake, high temperatures can develop at the fault plane so increasing pore pressure consequently to vaporization of the ground water already contained within rock.

In the coseismic phase, such increase can significantly affect slip evolution and speed and, furthermore, in the post-seismic phase it can control the

Aftershock

In seismology, an aftershock is a smaller earthquake that follows a larger earthquake, in the same area of the main shock, caused as the displaced crust adjusts to the effects of the main shock. Large earthquakes can have hundreds to thousand ...

sequence because, after the main event, pore pressure increase slowly propagates into the surrounding fracture network.

From the point of view of the

Mohr-Coulomb strength theory, an increase in fluid pressure reduces the normal stress acting on the fault plane that holds it in place, and fluids can exert a lubricating effect.

As thermal overpressurization may provide positive feedback between slip and strength fall at the fault plane, a common opinion is that it may enhance the faulting process instability. After the mainshock, the pressure gradient between the fault plane and the neighboring rock causes a fluid flow which increases pore pressure in the surrounding fracture networks; such increase may trigger new faulting processes by reactivating adjacent faults, giving rise to aftershocks.

Analogously, artificial pore pressure increase, by fluid injection in Earth's crust, may

induce seismicity.

Tidal forces

Tides

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables can ...

may induce some

seismicity

Seismicity is a measure encompassing earthquake occurrences, mechanisms, and magnitude at a given geographical location. As such, it summarizes a region's seismic activity. The term was coined by Beno Gutenberg and Charles Francis Richter in 19 ...

.

Earthquake clusters

Most earthquakes form part of a sequence, related to each other in terms of location and time.

Most earthquake clusters consist of small tremors that cause little to no damage, but there is a theory that earthquakes can recur in a regular pattern. Earthquake clustering has been observed, for example, in Parkfield, California where a long term research study is being conducted around the

Parkfield earthquake

Parkfield earthquake is a name given to various large earthquakes that occurred in the vicinity of the town of Parkfield, California, United States. The San Andreas fault runs through this town, and six successive magnitude 6 earthquakes occurred ...

cluster.

Aftershocks

An aftershock is an earthquake that occurs after a previous earthquake, the mainshock. Rapid changes of stress between rocks, and the stress from the original earthquake are the main causes of these aftershocks,

along with the crust around the ruptured

fault plane

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectonic ...

as it adjusts to the effects of the mainshock.

An aftershock is in the same region of the main shock but always of a smaller magnitude, however they can still be powerful enough to cause even more damage to buildings that were already previously damaged from the mainshock.

[ If an aftershock is larger than the mainshock, the aftershock is redesignated as the mainshock and the originalmain shock is redesignated as a ]foreshock

A foreshock is an earthquake that occurs before a larger seismic event (the mainshock) and is related to it in both time and space. The designation of an earthquake as ''foreshock'', ''mainshock'' or aftershock is only possible after the full sequ ...

. Aftershocks are formed as the crust around the displaced fault plane

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectonic ...

adjusts to the effects of the mainshock.[

]

Earthquake swarms

Earthquake swarms are sequences of earthquakes striking in a specific area within a short period. They are different from earthquakes followed by a series of aftershock

In seismology, an aftershock is a smaller earthquake that follows a larger earthquake, in the same area of the main shock, caused as the displaced crust adjusts to the effects of the main shock. Large earthquakes can have hundreds to thousand ...

s by the fact that no single earthquake in the sequence is obviously the main shock, so none has a notable higher magnitude than another. An example of an earthquake swarm is the 2004 activity at Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

. In August 2012, a swarm of earthquakes shook Southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most po ...

's Imperial Valley

, photo = Salton Sea from Space.jpg

, photo_caption = The Imperial Valley below the Salton Sea. The US-Mexican border runs diagonally across the lower left of the image.

, map_image = Newriverwatershed-1-.jpg

, map_caption = Map of Imperial ...

, showing the most recorded activity in the area since the 1970s.

Sometimes a series of earthquakes occur in what has been called an ''earthquake storm'', where the earthquakes strike a fault in clusters, each triggered by the shaking or stress redistribution of the previous earthquakes. Similar to aftershock

In seismology, an aftershock is a smaller earthquake that follows a larger earthquake, in the same area of the main shock, caused as the displaced crust adjusts to the effects of the main shock. Large earthquakes can have hundreds to thousand ...

s but on adjacent segments of fault, these storms occur over the course of years, and with some of the later earthquakes as damaging as the early ones. Such a pattern was observed in the sequence of about a dozen earthquakes that struck the North Anatolian Fault

The North Anatolian Fault (NAF) ( tr, Kuzey Anadolu Fay Hattı) is an active right-lateral strike-slip fault in northern Anatolia, and is the transform boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the Anatolian Plate. The fault extends westward fro ...

in Turkey in the 20th century and has been inferred for older anomalous clusters of large earthquakes in the Middle East.

Intensity and magnitude of earthquakes

Shaking of the earth is a common phenomenon that has been experienced by humans from the earliest of times. Before the development of strong-motion accelerometers, the intensity of a seismic event was estimated based on the observed effects. Magnitude and intensity are not directly related and calculated using different methods. The magnitude of an earthquake is a single value that describes the size of the earthquake at its source. Intensity is the measure of shaking at different locations around the earthquake. Intensity values vary from place to place, depending on distance from the earthquake and underlying rock or soil makeup.

The first scale for measuring earthquake magnitudes was developed by Charles F. Richter

Charles Francis Richter (; April 26, 1900 – September 30, 1985) was an American seismologist and physicist.

Richter is most famous as the creator of the Richter magnitude scale, which, until the development of the moment magnitude scale in 1 ...

in 1935. Subsequent scales (see seismic magnitude scales

Seismic magnitude scales are used to describe the overall strength or "size" of an earthquake. These are distinguished from seismic intensity scales that categorize the intensity or severity of ground shaking (quaking) caused by an earthquake at ...

) have retained a key feature, where each unit represents a ten-fold difference in the amplitude of the ground shaking and a 32-fold difference in energy. Subsequent scales are also adjusted to have approximately the same numeric value within the limits of the scale.

Although the mass media commonly reports earthquake magnitudes as "Richter magnitude" or "Richter scale", standard practice by most seismological authorities is to express an earthquake's strength on the moment magnitude

The moment magnitude scale (MMS; denoted explicitly with or Mw, and generally implied with use of a single M for magnitude) is a measure of an earthquake's magnitude ("size" or strength) based on its seismic moment. It was defined in a 1979 pape ...

scale, which is based on the actual energy released by an earthquake.

Frequency of occurrence

It is estimated that around 500,000 earthquakes occur each year, detectable with current instrumentation. About 100,000 of these can be felt.

It is estimated that around 500,000 earthquakes occur each year, detectable with current instrumentation. About 100,000 of these can be felt.Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

in Portugal, Turkey, New Zealand, Greece, Italy, India, Nepal and Japan. Larger earthquakes occur less frequently, the relationship being exponential

Exponential may refer to any of several mathematical topics related to exponentiation, including:

*Exponential function, also:

**Matrix exponential, the matrix analogue to the above

* Exponential decay, decrease at a rate proportional to value

*Exp ...

; for example, roughly ten times as many earthquakes larger than magnitude 4 occur in a particular time period than earthquakes larger than magnitude 5. In the (low seismicity) United Kingdom, for example, it has been calculated that the average recurrences are:

an earthquake of 3.7–4.6 every year, an earthquake of 4.7–5.5 every 10 years, and an earthquake of 5.6 or larger every 100 years. This is an example of the Gutenberg–Richter law

In seismology, the Gutenberg–Richter law (GR law) expresses the relationship between the magnitude and total number of earthquakes in any given region and time period of ''at least'' that magnitude.

: \!\,\log_ N = a - b M

or

: \!\,N = 10^

wher ...

.

The number of seismic stations has increased from about 350 in 1931 to many thousands today. As a result, many more earthquakes are reported than in the past, but this is because of the vast improvement in instrumentation, rather than an increase in the number of earthquakes. The United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

(USGS) estimates that, since 1900, there have been an average of 18 major earthquakes (magnitude 7.0–7.9) and one great earthquake (magnitude 8.0 or greater) per year, and that this average has been relatively stable. In recent years, the number of major earthquakes per year has decreased, though this is probably a statistical fluctuation rather than a systematic trend. More detailed statistics on the size and frequency of earthquakes is available from the United States Geological Survey.

A recent increase in the number of major earthquakes has been noted, which could be explained by a cyclical pattern of periods of intense tectonic activity, interspersed with longer periods of low intensity. However, accurate recordings of earthquakes only began in the early 1900s, so it is too early to categorically state that this is the case.

Most of the world's earthquakes (90%, and 81% of the largest) take place in the , horseshoe-shaped zone called the circum-Pacific seismic belt, known as the Pacific Ring of Fire

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt) is a region around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean where many Types of volcanic eruptions, volcanic eruptions and ...

, which for the most part bounds the Pacific Plate

The Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At , it is the largest tectonic plate.

The plate first came into existence 190 million years ago, at the triple junction between the Farallon, Phoenix, and Iza ...

. Massive earthquakes tend to occur along other plate boundaries too, such as along the Himalayan Mountains

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

.

With the rapid growth of mega-cities

A megacity is a very large city, typically with a population of more than 10 million people. Precise definitions vary: the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs in its 2018 "World Urbanization Prospects" report counted urban ...

such as Mexico City, Tokyo and Tehran in areas of high seismic risk

Seismic risk refers to the risk of damage from earthquake to a building, system, or other entity. Seismic risk has been defined, for most management purposes, as the potential economic, social and environmental consequences of hazardous events th ...

, some seismologists are warning that a single earthquake may claim the lives of up to three million people.

Induced seismicity

While most earthquakes are caused by movement of the Earth's tectonic plate

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

s, human activity can also produce earthquakes. Activities both above ground and below may change the stresses and strains on the crust, including building reservoirs, extracting resources such as coal or oil, and injecting fluids underground for waste disposal or fracking

Fracking (also known as hydraulic fracturing, hydrofracturing, or hydrofracking) is a well stimulation technique involving the fracturing of bedrock formations by a pressurized liquid. The process involves the high-pressure injection of "frack ...

. Most of these earthquakes have small magnitudes. The 5.7 magnitude 2011 Oklahoma earthquake

The 2011 Oklahoma earthquake was a 5.7 magnitude intraplate earthquake which occurred near Prague, Oklahoma on November 5 at 10:53 p.m. CDT (03:53 UTC November 6) in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The epicenter of the ear ...

is thought to have been caused by disposing wastewater from oil production into injection wells

An injection well is a device that places fluid deep underground into porous rock formations, such as sandstone or limestone, or into or below the shallow soil layer. The fluid may be water, wastewater, brine (salt water), or water mixed with indu ...

, and studies point to the state's oil industry as the cause of other earthquakes in the past century. A Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

paper suggested that the 8.0 magnitude 2008 Sichuan earthquake was induced by loading from the Zipingpu Dam

Zipingpu Dam (紫坪铺水利枢纽) is an embankment dam on the Min River (Sichuan), Min River near the city of Dujiangyan City, Dujiangyan, Sichuan Province in southwest China. It consists of four Electrical generator, generators with a total ge ...

, though the link has not been conclusively proved.

Measuring and locating earthquakes

The instrumental scales used to describe the size of an earthquake began with the Richter magnitude scale

The Richter scale —also called the Richter magnitude scale, Richter's magnitude scale, and the Gutenberg–Richter scale—is a measure of the strength of earthquakes, developed by Charles Francis Richter and presented in his landmark 1935 ...

in the 1930s. It is a relatively simple measurement of an event's amplitude, and its use has become minimal in the 21st century. Seismic waves

A seismic wave is a wave of acoustic energy that travels through the Earth. It can result from an earthquake, volcanic eruption, magma movement, a large landslide, and a large man-made explosion that produces low-frequency acoustic energy. S ...

travel through the Earth's interior

The internal structure of Earth is the solid portion of the Earth, excluding its atmosphere and hydrosphere. The structure consists of an outer silicate solid crust, a highly viscous asthenosphere and solid mantle, a liquid outer core whose ...

and can be recorded by seismometer

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground noises and shaking such as caused by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The outpu ...

s at great distances. The surface wave magnitude

The surface wave magnitude (M_s) scale is one of the magnitude scales used in seismology to describe the size of an earthquake. It is based on measurements of Rayleigh surface waves that travel along the uppermost layers of the Earth. This ma ...

was developed in the 1950s as a means to measure remote earthquakes and to improve the accuracy for larger events. The moment magnitude scale

The moment magnitude scale (MMS; denoted explicitly with or Mw, and generally implied with use of a single M for magnitude) is a measure of an earthquake's magnitude ("size" or strength) based on its seismic moment. It was defined in a 1979 pape ...

not only measures the amplitude of the shock but also takes into account the seismic moment Seismic moment is a quantity used by seismologists to measure the size of an earthquake. The scalar seismic moment M_0 is defined by the equation

M_0=\mu AD, where

*\mu is the shear modulus of the rocks involved in the earthquake (in pascals (Pa) ...

(total rupture area, average slip of the fault, and rigidity of the rock). The Japan Meteorological Agency seismic intensity scale

The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) Seismic Intensity Scale (known in Japan as the Shindo seismic scale) is a seismic intensity scale used in Japan to categorize the intensity of local ground shaking caused by earthquakes.

The JMA intensi ...

, the Medvedev–Sponheuer–Karnik scale

The Medvedev–Sponheuer–Karnik scale, also known as the MSK or MSK-64, is a macroseismic intensity scale used to evaluate the severity of ground shaking on the basis of observed effects in an area where an earthquake transpires.

The scale was f ...

, and the Mercalli intensity scale

The Modified Mercalli intensity scale (MM, MMI, or MCS), developed from Giuseppe Mercalli's Mercalli intensity scale of 1902, is a seismic intensity scale used for measuring the intensity of shaking produced by an earthquake. It measures the eff ...

are based on the observed effects and are related to the intensity of shaking.

Seismic waves

Every earthquake produces different types of seismic waves, which travel through rock with different velocities:

* Longitudinal P-waves

A P wave (primary wave or pressure wave) is one of the two main types of elastic body waves, called seismic waves in seismology. P waves travel faster than other seismic waves and hence are the first signal from an earthquake to arrive at any ...

(shock- or pressure waves)

* Transverse S-waves

__NOTOC__

In seismology and other areas involving elastic waves, S waves, secondary waves, or shear waves (sometimes called elastic S waves) are a type of elastic wave and are one of the two main types of elastic body waves, so named because th ...

(both body waves)

* Surface wave

In physics, a surface wave is a mechanical wave that propagates along the Interface (chemistry), interface between differing media. A common example is gravity waves along the surface of liquids, such as ocean waves. Gravity waves can also occu ...

s – ( Rayleigh and Love

Love encompasses a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most sublime virtue or good habit, the deepest Interpersonal relationship, interpersonal affection, to the simplest pleasure. An example of this range of ...

waves)

Speed of seismic waves

Propagation velocity

The phase velocity of a wave is the rate at which the wave propagates in any medium. This is the velocity at which the phase of any one frequency component of the wave travels. For such a component, any given phase of the wave (for example, ...

of the seismic waves through solid rock ranges from approx. up to , depending on the density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematical ...

and elasticity

Elasticity often refers to:

*Elasticity (physics), continuum mechanics of bodies that deform reversibly under stress

Elasticity may also refer to:

Information technology

* Elasticity (data store), the flexibility of the data model and the cl ...

of the medium. In the Earth's interior, the shock- or P-waves travel much faster than the S-waves (approx. relation 1.7:1). The differences in travel time from the epicenter

The epicenter, epicentre () or epicentrum in seismology is the point on the Earth's surface directly above a hypocenter or focus, the point where an earthquake or an underground explosion originates.

Surface damage

Before the instrumental pe ...

to the observatory are a measure of the distance and can be used to image both sources of earthquakes and structures within the Earth. Also, the depth of the hypocenter

In seismology, a hypocenter or hypocentre () is the point of origin of an earthquake or a subsurface nuclear explosion. A synonym is the focus of an earthquake.

Earthquakes

An earthquake's hypocenter is the position where the strain energy s ...

can be computed roughly.

P-wave speed

Upper crust soils and unconsolidated sediments: per second

Upper crust solid rock: per second

Lower crust: per second

Deep mantle: per second.

S-waves speed

Light sediments: per second in

Earths crust: per second

Deep mantle: per second

Seismic wave arrival

As a consequence, the first waves of a distant earthquake arrive at an observatory via the Earth's mantle.

On average, the kilometer distance to the earthquake is the number of seconds between the P- and S-wave times 8. Slight deviations are caused by inhomogeneities of subsurface structure. By such analysis of seismograms, the Earth's core was located in 1913 by Beno Gutenberg

Beno Gutenberg (; June 4, 1889 – January 25, 1960) was a German-American seismologist who made several important contributions to the science. He was a colleague and mentor of Charles Francis Richter at the California Institute of Technol ...

.

S-waves and later arriving surface waves do most of the damage compared to P-waves. P-waves squeeze and expand the material in the same direction they are traveling, whereas S-waves shake the ground up and down and back and forth.

Earthquake location and reporting

Earthquakes are not only categorized by their magnitude but also by the place where they occur. The world is divided into 754 Flinn–Engdahl regions

The Flinn-Engdahl regions (or F-E regions) comprise a set of contiguous seismic zones which cover the Earth's surface. In seismology, they are the standard for localizing earthquakes. The scheme was proposed in 1965 by Edward A. Flinn and E. R. E ...

(F-E regions), which are based on political and geographical boundaries as well as seismic activity. More active zones are divided into smaller F-E regions whereas less active zones belong to larger F-E regions.

Standard reporting of earthquakes includes its magnitude

Magnitude may refer to:

Mathematics

*Euclidean vector, a quantity defined by both its magnitude and its direction

*Magnitude (mathematics), the relative size of an object

*Norm (mathematics), a term for the size or length of a vector

*Order of ...

, date and time of occurrence, geographic coordinates

The geographic coordinate system (GCS) is a spherical or ellipsoidal coordinate system for measuring and communicating positions directly on the Earth as latitude and longitude. It is the simplest, oldest and most widely used of the various ...

of its epicenter

The epicenter, epicentre () or epicentrum in seismology is the point on the Earth's surface directly above a hypocenter or focus, the point where an earthquake or an underground explosion originates.

Surface damage

Before the instrumental pe ...

, depth of the epicenter, geographical region, distances to population centers, location uncertainty, several parameters that are included in USGS earthquake reports (number of stations reporting, number of observations, etc.), and a unique event ID.

Although relatively slow seismic waves have traditionally been used to detect earthquakes, scientists realized in 2016 that gravitational measurements could provide instantaneous detection of earthquakes, and confirmed this by analyzing gravitational records associated with the 2011 Tohoku-Oki ("Fukushima") earthquake.

Effects of earthquakes

The effects of earthquakes include, but are not limited to, the following:

The effects of earthquakes include, but are not limited to, the following:

Shaking and ground rupture

Shaking and

Shaking and ground rupture

In seismology, surface rupture (or ground rupture, or ground displacement) is the visible offset of the ground surface when an earthquake rupture along a fault affects the Earth's surface. Surface rupture is opposed by buried rupture, where the ...

are the main effects created by earthquakes, principally resulting in more or less severe damage to buildings and other rigid structures. The severity of the local effects depends on the complex combination of the earthquake magnitude

Magnitude may refer to:

Mathematics

*Euclidean vector, a quantity defined by both its magnitude and its direction

*Magnitude (mathematics), the relative size of an object

*Norm (mathematics), a term for the size or length of a vector

*Order of ...

, the distance from the epicenter

The epicenter, epicentre () or epicentrum in seismology is the point on the Earth's surface directly above a hypocenter or focus, the point where an earthquake or an underground explosion originates.

Surface damage

Before the instrumental pe ...

, and the local geological and geomorphological conditions, which may amplify or reduce wave propagation

Wave propagation is any of the ways in which waves travel. Single wave propagation can be calculated by 2nd order wave equation ( standing wavefield) or 1st order one-way wave equation.

With respect to the direction of the oscillation relative to ...

. The ground-shaking is measured by ground acceleration

Peak ground acceleration (PGA) is equal to the maximum ground acceleration that occurred during earthquake shaking at a location. PGA is equal to the amplitude of the largest absolute acceleration recorded on an wikt:accelerogram, accelerogram at a ...

.

Specific local geological, geomorphological, and geostructural features can induce high levels of shaking on the ground surface even from low-intensity earthquakes. This effect is called site or local amplification. It is principally due to the transfer of the seismic

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

motion from hard deep soils to soft superficial soils and the effects of seismic energy focalization owing to the typical geometrical setting of such deposits.

Ground rupture is a visible breaking and displacement of the Earth's surface along the trace of the fault, which may be of the order of several meters in the case of major earthquakes. Ground rupture is a major risk for large engineering structures such as dams

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use, ...

, bridges, and nuclear power stations

A nuclear power plant (NPP) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power stations, heat is used to generate steam that drives a steam turbine connected to a generator that produces elec ...

and requires careful mapping of existing faults to identify any that are likely to break the ground surface within the life of the structure.

Soil liquefaction

Soil liquefaction occurs when, because of the shaking, water-saturated granular

Granularity (also called graininess), the condition of existing in granules or grains, refers to the extent to which a material or system is composed of distinguishable pieces. It can either refer to the extent to which a larger entity is subd ...

material (such as sand) temporarily loses its strength and transforms from a solid to a liquid. Soil liquefaction may cause rigid structures, like buildings and bridges, to tilt or sink into the liquefied deposits. For example, in the 1964 Alaska earthquake

The 1964 Alaskan earthquake, also known as the Great Alaskan earthquake and Good Friday earthquake, occurred at 5:36 PM AKST on Good Friday, March 27. , soil liquefaction caused many buildings to sink into the ground, eventually collapsing upon themselves.

Human impacts

Physical damage from an earthquake will vary depending on the intensity of shaking in a given area and they type of population. Undeserved and developing communities frequently experience more severe impacts (and longer lasting) from a seismic event compared to well developed communities. Impacts may include:

* Injuries and loss of life

* Damage to critical infrastructure (short and long term)

** Roads, bridges and public transportation networks

** Water, power, swear and gas interruption

** Communication systems

* Loss of critical community services including hospitals, police and fire

* General

Physical damage from an earthquake will vary depending on the intensity of shaking in a given area and they type of population. Undeserved and developing communities frequently experience more severe impacts (and longer lasting) from a seismic event compared to well developed communities. Impacts may include:

* Injuries and loss of life

* Damage to critical infrastructure (short and long term)

** Roads, bridges and public transportation networks

** Water, power, swear and gas interruption

** Communication systems

* Loss of critical community services including hospitals, police and fire

* General property damage

Property damage (or cf. criminal damage in England and Wales) is damage or destruction of real or tangible personal property, caused by negligence, willful destruction, or act of nature.

It is similar to vandalism and arson (destroying propert ...

* Collapse or destabilization (potentially leading to future collapse) of buildings

With these impacts and others, the aftermath may bring disease, lack of basic necessities, mental consequences such as panic attacks, depression to survivors, and higher insurance premiums. Recovery times will vary based off the level of damage along with the socioeconomic status of the impacted community.

Landslides

Earthquakes can produce slope instability leading to landslides, a major geological hazard. Landslide danger may persist while emergency personnel are attempting rescue work.

Fires

Earthquakes can cause fires by damaging

Earthquakes can cause fires by damaging electrical power

Electric power is the rate at which electrical energy is transferred by an electric circuit. The SI unit of power is the watt, one joule per second. Standard prefixes apply to watts as with other SI units: thousands, millions and billions of ...

or gas lines. In the event of water mains rupturing and a loss of pressure, it may also become difficult to stop the spread of a fire once it has started. For example, more deaths in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity sha ...

were caused by fire than by the earthquake itself.

Tsunami

Tsunamis are long-wavelength, long-period sea waves produced by the sudden or abrupt movement of large volumes of water—including when an earthquake occurs at sea. In the open ocean, the distance between wave crests can surpass , and the wave periods can vary from five minutes to one hour. Such tsunamis travel 600–800 kilometers per hour (373–497 miles per hour), depending on water depth. Large waves produced by an earthquake or a submarine landslide can overrun nearby coastal areas in a matter of minutes. Tsunamis can also travel thousands of kilometers across open ocean and wreak destruction on far shores hours after the earthquake that generated them.

Tsunamis are long-wavelength, long-period sea waves produced by the sudden or abrupt movement of large volumes of water—including when an earthquake occurs at sea. In the open ocean, the distance between wave crests can surpass , and the wave periods can vary from five minutes to one hour. Such tsunamis travel 600–800 kilometers per hour (373–497 miles per hour), depending on water depth. Large waves produced by an earthquake or a submarine landslide can overrun nearby coastal areas in a matter of minutes. Tsunamis can also travel thousands of kilometers across open ocean and wreak destruction on far shores hours after the earthquake that generated them.[

]

Floods

Floods may be secondary effects of earthquakes, if dams are damaged. Earthquakes may cause landslips to dam rivers, which collapse and cause floods.

The terrain below the Sarez Lake

Sarez Lake (russian: Сарезское озеро; tg, Сарез кӯл, Sarez Kūl) is a lake in Rushon District of Gorno-Badakhshan province, Tajikistan. Length about , depth few hundred meters, water surface elevation about above sea leve ...

in Tajikistan is in danger of catastrophic flooding if the landslide dam

A landslide dam or barrier lake is the natural damming of a river by some kind of landslide, such as a debris flow, rock avalanche or volcanic eruption. If the damming landslide is caused by an earthquake, it may also be called a quake lake. Some ...

formed by the earthquake, known as the Usoi Dam

The Usoi Dam is a natural landslide dam along the Murghab River (Tajikistan), Murghab River in Tajikistan. At high, it is the tallest dam in the world, either natural or man-made. The dam was created on February 18, 1911, when the 7.4-Surface wav ...

, were to fail during a future earthquake. Impact projections suggest the flood could affect roughly 5 million people.

Major earthquakes

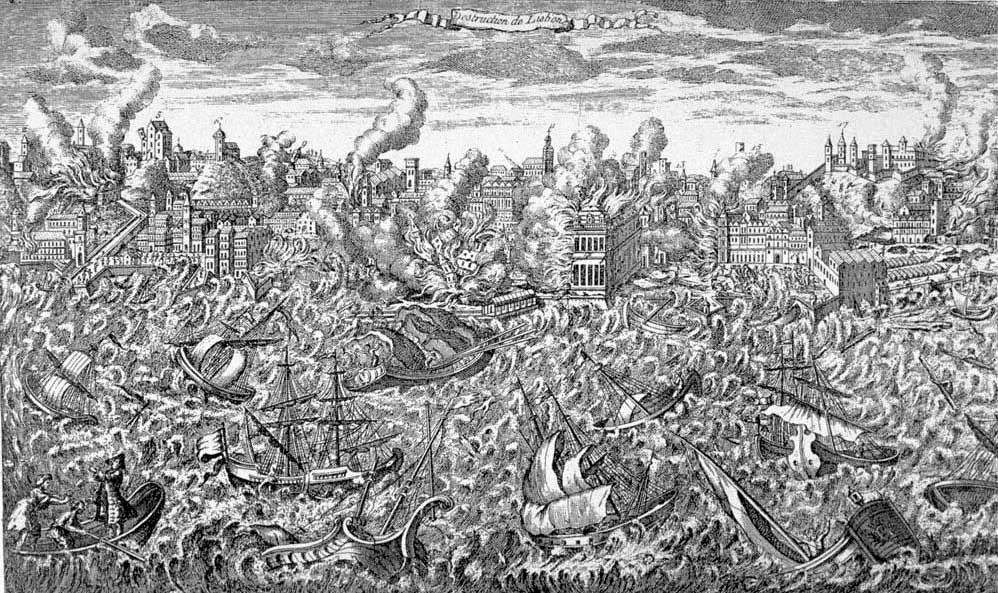

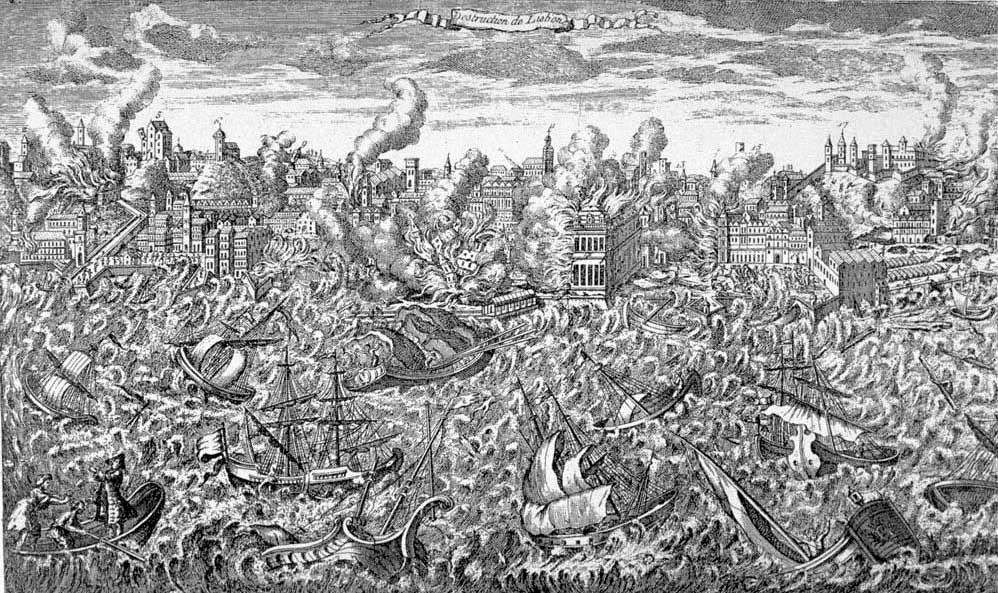

One of the most devastating earthquakes in recorded history was the

One of the most devastating earthquakes in recorded history was the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake

The 1556 Shaanxi earthquake (formerly romanized ''Shensi''), known in Chinese colloquially by its regnal year as "" ('' Jiājìng Dàdìzhèn'') or officially by its epicenter as "" ('' Huàxiàn Dìzhèn''), occurred in the early morning of 23 ...

, which occurred on 23 January 1556 in Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see #Name, § Name) is a landlocked Provinces of China, province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichu ...

, China. More than 830,000 people died. Most houses in the area were yaodong

A yaodong () or "house cave" is a particular form of earth shelter dwelling common in the Loess Plateau in China's north. They are generally carved out of a hillside or excavated horizontally from a central "sunken courtyard".

The earth that su ...

s—dwellings carved out of loess

Loess (, ; from german: Löss ) is a clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loess or similar deposits.

Loess is a periglacial or aeolian ...

hillsides—and many victims were killed when these structures collapsed. The 1976 Tangshan earthquake

The 1976 Tangshan earthquake () was a 7.6 earthquake that hit the region around Tangshan, Hebei, China, at 3:42 a.m. on 28 July 1976. The maximum intensity of the earthquake was XI (''Extreme'') on the Mercalli scale. In minutes, 85 percent ...

, which killed between 240,000 and 655,000 people, was the deadliest of the 20th century.

The 1960 Chilean earthquake

The 1960 Valdivia earthquake and tsunami ( es, link=no, Terremoto de Valdivia) or the Great Chilean earthquake (''Gran terremoto de Chile'') on 22 May 1960 was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded. Various studies have placed it at 9.4– ...

is the largest earthquake that has been measured on a seismograph, reaching 9.5 magnitude on 22 May 1960.Good Friday earthquake

The 1964 Alaskan earthquake, also known as the Great Alaskan earthquake and Good Friday earthquake, occurred at 5:36 PM AKST on Good Friday, March 27. (27 March 1964), which was centered in Prince William Sound

Prince William Sound (Sugpiaq: ''Suungaaciq'') is a sound of the Gulf of Alaska on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is located on the east side of the Kenai Peninsula. Its largest port is Valdez, at the southern terminus of the Tr ...

, Alaska. The ten largest recorded earthquakes have all been megathrust earthquake

Megathrust earthquakes occur at convergent plate boundaries, where one tectonic plate is forced underneath another. The earthquakes are caused by slip along the thrust fault that forms the contact between the two plates. These interplate earthqua ...

s; however, of these ten, only the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake

An earthquake and a tsunami, known as the Boxing Day Tsunami and, by the scientific community, the Sumatra–Andaman earthquake, occurred at 07:58:53 local time (UTC+7) on 26 December 2004, with an epicentre off the west coast of northern Suma ...

is simultaneously one of the deadliest earthquakes in history.

Earthquakes that caused the greatest loss of life, while powerful, were deadly because of their proximity to either heavily populated areas or the ocean, where earthquakes often create tsunamis

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater expl ...

that can devastate communities thousands of kilometers away. Regions most at risk for great loss of life include those where earthquakes are relatively rare but powerful, and poor regions with lax, unenforced, or nonexistent seismic building codes.

Prediction

Earthquake prediction

Earthquake prediction is a branch of the science of seismology concerned with the specification of the time, location, and magnitude of future earthquakes within stated limits, and particularly "the determination of parameters for the ''next'' s ...

is a branch of the science of seismology

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

concerned with the specification of the time, location, and magnitude

Magnitude may refer to:

Mathematics

*Euclidean vector, a quantity defined by both its magnitude and its direction

*Magnitude (mathematics), the relative size of an object

*Norm (mathematics), a term for the size or length of a vector

*Order of ...

of future earthquakes within stated limits. Many methods have been developed for predicting the time and place in which earthquakes will occur. Despite considerable research efforts by seismologist

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

s, scientifically reproducible predictions cannot yet be made to a specific day or month.[Earthquake Prediction](_blank)

Ruth Ludwin, U.S. Geological Survey.

Forecasting

While forecasting

Forecasting is the process of making predictions based on past and present data. Later these can be compared (resolved) against what happens. For example, a company might estimate their revenue in the next year, then compare it against the actual ...

is usually considered to be a type of prediction

A prediction (Latin ''præ-'', "before," and ''dicere'', "to say"), or forecast, is a statement about a future event or data. They are often, but not always, based upon experience or knowledge. There is no universal agreement about the exact ...

, earthquake forecasting

Earthquake forecasting is a branch of the science of seismology concerned with the probabilistic assessment of general earthquake seismic hazard, including the frequency and magnitude of damaging earthquakes in a given area over years or decades ...

is often differentiated from earthquake prediction

Earthquake prediction is a branch of the science of seismology concerned with the specification of the time, location, and magnitude of future earthquakes within stated limits, and particularly "the determination of parameters for the ''next'' s ...

. Earthquake forecasting is concerned with the probabilistic assessment of general earthquake hazard, including the frequency and magnitude of damaging earthquakes in a given area over years or decades. For well-understood faults the probability that a segment may rupture during the next few decades can be estimated.

Earthquake warning system

An earthquake warning system or earthquake early warning system is a system of accelerometers, seismometers, communication, computers, and alarms that is devised for notifying adjoining regions of a substantial earthquake while it is in progress ...

s have been developed that can provide regional notification of an earthquake in progress, but before the ground surface has begun to move, potentially allowing people within the system's range to seek shelter before the earthquake's impact is felt.

Preparedness

The objective of earthquake engineering

Earthquake engineering is an interdisciplinary branch of engineering that designs and analyzes structures, such as buildings and bridges, with earthquakes in mind. Its overall goal is to make such structures more resistant to earthquakes. An earth ...

is to foresee the impact of earthquakes on buildings and other structures and to design such structures to minimize the risk of damage. Existing structures can be modified by seismic retrofitting

Seismic retrofitting is the modification of existing built environment, structures to make them more resistant to seismology, seismic activity, ground motion, or soil failure due to earthquakes. With better understanding of seismic demand on stru ...

to improve their resistance to earthquakes. Earthquake insurance

Earthquake insurance is a form of property insurance that pays the policyholder in the event of an earthquake that causes damage to the property. Most ordinary homeowners insurance policies do not cover earthquake damage.

Most earthquake insuran ...

can provide building owners with financial protection against losses resulting from earthquakes. Emergency management

Emergency management or disaster management is the managerial function charged with creating the framework within which communities reduce vulnerability to hazards and cope with disasters. Emergency management, despite its name, does not actuall ...

strategies can be employed by a government or organization to mitigate risks and prepare for consequences.

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is intelligence—perceiving, synthesizing, and inferring information—demonstrated by machines, as opposed to intelligence displayed by animals and humans. Example tasks in which this is done include speech re ...

may help to assess buildings and plan precautionary operations: the Igor expert system

In artificial intelligence, an expert system is a computer system emulating the decision-making ability of a human expert.

Expert systems are designed to solve complex problems by reasoning through bodies of knowledge, represented mainly as if� ...

is part of a mobile laboratory that supports the procedures leading to the seismic assessment of masonry buildings and the planning of retrofitting operations on them. It has been successfully applied to assess buildings in Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

, Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

.

Individuals can also take preparedness steps like securing water heaters

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a s ...

and heavy items that could injure someone, locating shutoffs for utilities, and being educated about what to do when the shaking starts. For areas near large bodies of water, earthquake preparedness encompasses the possibility of a tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater explo ...

caused by a large earthquake.

Historical views

From the lifetime of the Greek philosopher

From the lifetime of the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀναξαγόρας, ''Anaxagóras'', "lord of the assembly"; 500 – 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, ...

in the 5th century BCE to the 14th century CE, earthquakes were usually attributed to "air (vapors) in the cavities of the Earth."Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded him ...

of Miletus (625–547 BCE) was the only documented person who believed that earthquakes were caused by tension between the earth and water.[ Other theories existed, including the Greek philosopher Anaxamines' (585–526 BCE) beliefs that short incline episodes of dryness and wetness caused seismic activity. The Greek philosopher Democritus (460–371 BCE) blamed water in general for earthquakes.][ ]Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

called earthquakes "underground thunderstorms".[

]

In culture

Mythology and religion

In Norse mythology

Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia, and into the Nordic folklore of the modern period ...

, earthquakes were explained as the violent struggling of the god Loki

Loki is a god in Norse mythology. According to some sources, Loki is the son of Fárbauti (a jötunn) and Laufey (mentioned as a goddess), and the brother of Helblindi and Býleistr. Loki is married to Sigyn and they have two sons, Narfi or Na ...

. When Loki, god

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

of mischief and strife, murdered Baldr

Baldr (also Balder, Baldur) is a god in Germanic mythology. In Norse mythology, Baldr (Old Norse: ) is a son of the god Odin and the goddess Frigg, and has numerous brothers, such as Thor and Váli. In wider Germanic mythology, the god was kno ...

, god of beauty and light, he was punished by being bound in a cave with a poisonous serpent placed above his head dripping venom. Loki's wife Sigyn

Sigyn (Old Norse: "(woman) friend of victory"Orchard (1997:146).) is a deity from Norse mythology. She is attested in the ''Poetic Edda'', compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the ''Prose Edda'', written in the 13t ...

stood by him with a bowl to catch the poison, but whenever she had to empty the bowl the poison dripped on Loki's face, forcing him to jerk his head away and thrash against his bonds, which caused the earth to tremble.

In Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the Cosmogony, origin and Cosmology#Metaphysical co ...

, Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

was the cause and god of earthquakes. When he was in a bad mood, he struck the ground with a trident

A trident is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm.

The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the God of the Sea in classical mythology. The trident may occasionally be held by other marine ...

, causing earthquakes and other calamities. He also used earthquakes to punish and inflict fear upon people as revenge.Japanese mythology

Japanese mythology is a collection of traditional stories, folktales, and beliefs that emerged in the islands of the Japanese archipelago. Shinto and Buddhist traditions are the cornerstones of Japanese mythology. The history of thousands of year ...

, Namazu

In Japanese mythology, the or is a giant underground catfish who causes earthquakes.