Early world maps on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The earliest known

A Babylonian world map, known as the ''Imago Mundi'', is commonly dated to the 6th century BCE.British Museum Inv. No. 92687

A Babylonian world map, known as the ''Imago Mundi'', is commonly dated to the 6th century BCE.British Museum Inv. No. 92687

"6th C BC approx". see also: Siebold, Ji

via henry-davis.com - accessed 2008-02-04. First published 1899, formerly also dated to an earlier period, BCE. The map as reconstructed by Eckhard Unger shows Babylon on the Euphrates, surrounded by a circular landmass including

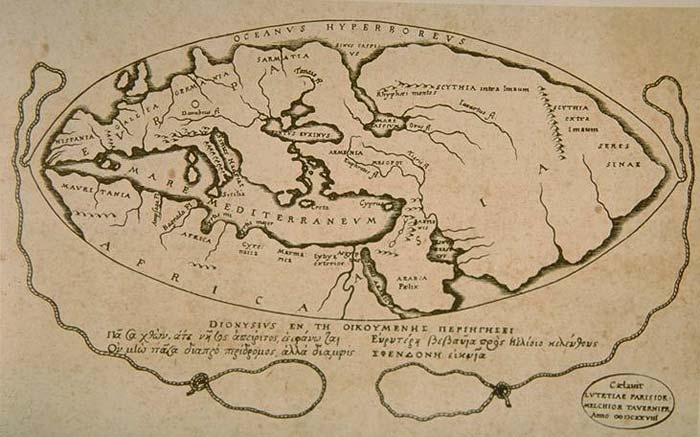

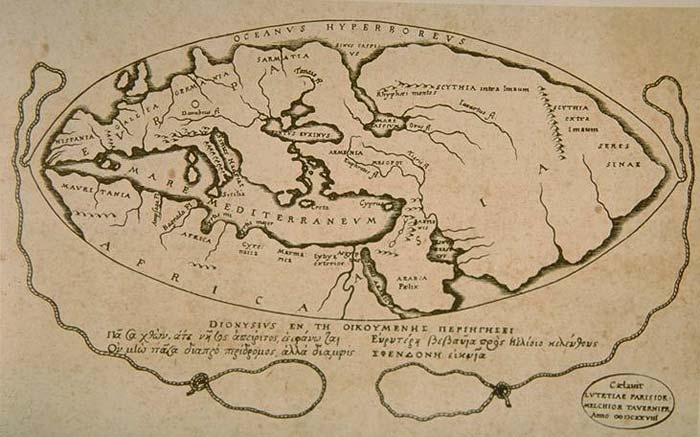

Anaximander (died c. 546 BCE) is credited with having created one of the first maps of the world, which was circular in form and showed the known lands of the world grouped around the

Anaximander (died c. 546 BCE) is credited with having created one of the first maps of the world, which was circular in form and showed the known lands of the world grouped around the

Hecataeus of Miletus (died BCE) is credited with a work entitled '' Periodos Ges'' ("Travels round the Earth" or "World Survey'), in two books each organized in the manner of a

Hecataeus of Miletus (died BCE) is credited with a work entitled '' Periodos Ges'' ("Travels round the Earth" or "World Survey'), in two books each organized in the manner of a

Pomponius is unique among ancient geographers in that, after dividing the Earth into five zones, of which two only were habitable, he asserts the existence of

Pomponius is unique among ancient geographers in that, after dividing the Earth into five zones, of which two only were habitable, he asserts the existence of

Surviving texts of

Surviving texts of

Around 550

Around 550

The Albi Mappa Mundi is a medieval map of the world, included in a manuscript of the second half of the 8th century, preserved in the old collection of the library Pierre-Amalric in

The Albi Mappa Mundi is a medieval map of the world, included in a manuscript of the second half of the 8th century, preserved in the old collection of the library Pierre-Amalric in

This map appears in a copy of a classical work on geography, the Latin version by

This map appears in a copy of a classical work on geography, the Latin version by

world map

A world map is a map of most or all of the surface of Earth. World maps, because of their scale, must deal with the problem of map projection, projection. Maps rendered in two dimensions by necessity distort the display of the three-dimensiona ...

s date to classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations ...

, the oldest examples of the 6th to 5th centuries BCE still based on the flat Earth

The flat-Earth model is an archaic and scientifically disproven conception of Earth's shape as a plane or disk. Many ancient cultures subscribed to a flat-Earth cosmography, including Greece until the classical period (5th century BC), t ...

paradigm.

World maps assuming a spherical Earth

Spherical Earth or Earth's curvature refers to the approximation of figure of the Earth as a sphere.

The earliest documented mention of the concept dates from around the 5th century BC, when it appears in the writings of Greek philosophers. ...

first appear in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

.

The developments of Greek geography

Greece is a country of the Balkans, in Southeastern Europe, bordered to the north by Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria; to the east by Turkey, and is surrounded to the east by the Aegean Sea, to the south by the Cretan and the Libyan Seas, an ...

during this time, notably by Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexand ...

and Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, wikt:Ποσειδώνιος, Ποσειδώνιος , "of Poseidon") "of Apamea (Syria), Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greeks, Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geog ...

culminated in the Roman era, with Ptolemy's world map (2nd century CE), which would remain authoritative throughout the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

.

Since Ptolemy, knowledge of the approximate size of the Earth allowed cartographers to estimate the extent of their geographical knowledge, and to indicate parts of the planet known to exist but not yet explored as '' terra incognita''.

With the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafari ...

, during the 15th to 18th centuries, world maps became increasingly accurate; exploration of Antarctica, Australia, and the interior of Africa by western mapmakers was left to the 19th and early 20th century.

Antiquity

Bronze Age “Saint-Bélec slab”

The Saint-Bélec slab discovered in 1900 byPaul du Châtellier

Paul du Châtellier (13 November 1833 - March 1911) was a French prehistorian.

In 1900, he discovered the Saint-Bélec slab, which is believed to be one of the world's oldest maps.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Di Chatellier, Paul

19th-century ...

, in Finistère, France, is dated to between 1900 BCE and 1640 BCE. A recent analysis, published in the Bulletin of the French Prehistoric Society, has shown that the slab is a three-dimensional representation of the River Odet valley in Finistère, France. This would make the Saint-Bélec slab the oldest known map of a territory in the world. According to the authors, the map probably wasn’t used for navigation, but rather to show the political power and territorial extent of a local ruler’s domain of the early Bronze age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

.

Babylonian ''Imago Mundi'' (c. 6th c. BCE)

"6th C BC approx". see also: Siebold, Ji

via henry-davis.com - accessed 2008-02-04. First published 1899, formerly also dated to an earlier period, BCE. The map as reconstructed by Eckhard Unger shows Babylon on the Euphrates, surrounded by a circular landmass including

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the As ...

, Urartu

Urartu (; Assyrian: ',Eberhard Schrader, ''The Cuneiform inscriptions and the Old Testament'' (1885), p. 65. Babylonian: ''Urashtu'', he, אֲרָרָט ''Ararat'') is a geographical region and Iron Age kingdom also known as the Kingdom of Va ...

(Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ...

) and several cities, in turn surrounded by a "bitter river" (Oceanus

In Greek mythology, Oceanus (; grc-gre, , Ancient Greek pronunciation: , also Ὠγενός , Ὤγενος , or Ὠγήν ) was a Titans (mythology), Titan son of Uranus (mythology), Uranus and Gaia, the husband of his sister the Titan Tethy ...

), with eight outlying regions (''nagu'') arranged around it in the shape of triangles, so as to form a star. The accompanying text mentions a distance of seven ''beru'' between the outlying regions.

The descriptions of five of them have survived:

*the third region is where "the winged bird ends not his flight," i.e., cannot reach.

*on the fourth region "the light is brighter than that of sunset or stars": it lay in the northwest, and after sunset in summer was practically in semi-obscurity.

*The fifth region, due north, lay in complete darkness, a land "where one sees nothing," and "the sun is not visible."

*the sixth region, "where a horned bull dwells and attacks the newcomer"

*the seventh region lay in the east and is "where the morning dawns."

Anaximander (c. 610–546 BCE)

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans an ...

at the center. This was all surrounded by the ocean.

Hecataeus of Miletus (c. 550–476 BCE)

periplus

A periplus (), or periplous, is a manuscript document that lists the ports and coastal landmarks, in order and with approximate intervening distances, that the captain of a vessel could expect to find along a shore. In that sense, the periplus wa ...

, a point-to-point coastal survey. One on Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

, is essentially a periplus of the Mediterranean, describing each region in turn, reaching as far north as Scythia

Scythia ( Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

...

. The other book, on Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

, is arranged similarly to the ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

The ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' ( grc, Περίπλους τῆς Ἐρυθρᾶς Θαλάσσης, ', modern Greek '), also known by its Latin name as the , is a Greco-Roman periplus written in Koine Greek that describes navigation and ...

'' of which a version of the 1st century CE survives. Hecataeus described the countries and inhabitants of the known world, the account of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

being particularly comprehensive; the descriptive matter was accompanied by a map, based upon Anaximander's map of the Earth, which he corrected and enlarged. The work only survives in some 374 fragments, by far the majority being quoted in the geographical lexicon the ''Ethnica'', compiled by Stephanus of Byzantium

Stephanus or Stephan of Byzantium ( la, Stephanus Byzantinus; grc-gre, Στέφανος Βυζάντιος, ''Stéphanos Byzántios''; centuryAD), was a Byzantine grammarian and the author of an important geographical dictionary entitled ''Ethni ...

.

Eratosthenes (276–194 BCE)

Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexand ...

(276–194 BCE) drew an improved world map, incorporating information from the campaigns of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

and his successors. Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

became wider, reflecting the new understanding of the actual size of the continent. Eratosthenes was also the first geographer to incorporate parallels and meridians within his cartographic depictions, attesting to his understanding of the spherical nature of the Earth.

Posidonius (c. 135–51 BCE)

Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, wikt:Ποσειδώνιος, Ποσειδώνιος , "of Poseidon") "of Apamea (Syria), Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greeks, Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geog ...

(or Poseidonius) of Apameia (c. 135–51 BCE), was a Greek Stoic philosopher who traveled throughout the Roman world and beyond and was a celebrated polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

throughout the Greco-Roman world, like Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

and Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexand ...

. His work "about the ocean and the adjacent areas" was a general geographical discussion, showing how all the forces had an effect on each other and applied also to human life. He measured the Earth's circumference by reference to the position of the star Canopus

Canopus is the brightest star in the southern constellation of Carina and the second-brightest star in the night sky. It is also designated α Carinae, which is Latinised to Alpha Carinae. With a visual apparent magnitude of ...

. His measure of 240,000 stadia translates to , close to the actual circumference of .

He was informed in his approach by Eratosthenes, who a century earlier used the elevation of the Sun at different latitudes. Both men's figures for the Earth's circumference were uncannily accurate, aided in each case by mutually compensating errors in measurement. However, the version of Posidonius' calculation popularised by Strabo was revised by correcting the distance between Rhodes and Alexandria to 3,750 stadia, resulting in a circumference of 180,000 stadia, or . Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

discussed and favored this revised figure of Posidonius over Eratosthenes in his ''Geographia'', and during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

scholars divided into two camps regarding the circumference of the Earth, one side identifying with Eratosthenes' calculation and the other with Posidonius' 180,000 stadion measure.

Strabo (c. 64 BCE – 24 CE)

Strabo is mostly famous for his 17-volume work ''Geographica'', which presented a descriptive history of people and places from different regions of the world known to his era.''Strabonis Geographica'', Book 17, Chapter 7. The ''Geographica'' first appeared in Western Europe in Rome as a Latin translation issued around 1469. Although Strabo referenced the antique Greek astronomers Eratosthenes andHipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equ ...

and acknowledged their astronomical and mathematical efforts towards geography, he claimed that a descriptive approach was more practical. ''Geographica'' provides a valuable source of information on the ancient world, especially when this information is corroborated by other sources. Within the books of ''Geographica'' is a map of Europe. Whole world maps according to Strabo are reconstructions from his written text.

Pomponius Mela (c. 43 CE)

Pomponius is unique among ancient geographers in that, after dividing the Earth into five zones, of which two only were habitable, he asserts the existence of

Pomponius is unique among ancient geographers in that, after dividing the Earth into five zones, of which two only were habitable, he asserts the existence of antichthones

Antichthones, in geography, are those peoples who inhabit the antipodes, regions on opposite sides of the Earth. The word is compounded of the Greek ''ὰντὶ'' ("opposed") and ''χθών'' ("earth").

Classical and Medieval Europe considere ...

, people inhabiting the southern temperate zone inaccessible to the folk of the northern temperate regions due to the unbearable heat of the intervening torrid belt. On the divisions and boundaries of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

, Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, he repeats Eratosthenes; like all classical geographers from Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

(except Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

) he regards the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad s ...

as an inlet of the Northern Ocean, corresponding to the Persian (Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

) and Arabian (Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

) gulfs on the south.

Marinus of Tyre (c. 120 CE)

Marinus of Tyre's world maps were the first in theRoman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

to show China. Around 120 CE, Marinus wrote that the habitable world was bounded on the west by the Fortunate Islands

The Fortunate Isles or Isles of the Blessed ( grc, μακάρων νῆσοι, ''makárōn nêsoi'') were semi-legendary islands in the Atlantic Ocean, variously treated as a simple geographical location and as a winterless earthly paradise inhabit ...

. The text of his geographical treatise however is lost. He also invented the equirectangular projection

The equirectangular projection (also called the equidistant cylindrical projection or la carte parallélogrammatique projection), and which includes the special case of the plate carrée projection (also called the geographic projection, lat/lon ...

, which is still used in map creation today. A few of Marinus' opinions are reported by Ptolemy. Marinus was of the opinion that the '' Okeanos'' was separated into an eastern and a western part by the continents (Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

, Asia and Africa). He thought that the inhabited world stretched in latitude from Thule

Thule ( grc-gre, Θούλη, Thoúlē; la, Thūlē) is the most northerly location mentioned in ancient Greek and Roman literature and cartography. Modern interpretations have included Orkney, Shetland, northern Scotland, the island of Saar ...

(Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the ...

) to Agisymba (Tropic of Capricorn

The Tropic of Capricorn (or the Southern Tropic) is the circle of latitude that contains the subsolar point at the December (or southern) solstice. It is thus the southernmost latitude where the Sun can be seen directly overhead. It also reach ...

) and in longitude from the Isles of the Blessed to Shera (China). Marinus also coined the term Antarctic, referring to the opposite of the Arctic Circle. His chief legacy is that he first assigned to each place a proper latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north po ...

and longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek let ...

; he used a "Meridian of the Isles of the Blessed (Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Mo ...

or Cape Verde Islands

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

)" as the zero meridian.

Ptolemy (c. 150)

Surviving texts of

Surviving texts of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

's ''Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, a ...

'', first composed , note that he continued the use of Marinus's equirectangular projection for its regional maps while finding it inappropriate for maps of the entire known world. Instead, in Book VII of his work, he outlines three separate projections of increasing difficulty and fidelity. Ptolemy followed Marinus in underestimating the circumference of the world; combined with accurate absolute distances, this led him to also overestimate the length of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

in terms of degrees. His prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrary meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. Together, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian in a 360°-system) form a great ...

at the Fortunate Isles

The Fortunate Isles or Isles of the Blessed ( grc, μακάρων νῆσοι, ''makárōn nêsoi'') were semi-legendary islands in the Atlantic Ocean, variously treated as a simple geographical location and as a winterless earthly paradise inhabit ...

was therefore around 10 actual degrees further west of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

than intended, a mistake that was corrected by Al-Khwārizmī

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persians, Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in Mathematics ...

following the translation of Syriac editions of Ptolemy into Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

in the 9th century. The oldest surviving manuscripts of the work date to Maximus Planudes

Maximus Planudes ( grc-gre, Μάξιμος Πλανούδης, ''Máximos Planoúdēs''; ) was a Byzantine Greek monk, scholar, anthologist, translator, mathematician, grammarian and theologian at Constantinople. Through his translations from La ...

's restoration of the text a little before 1300 at Chora Monastery

'' '' tr, Kariye Mosque''

, image = Chora Church Constantinople 2007 panorama 002.jpg

, caption = Exterior rear view

, map_type = Istanbul Fatih

, map_size = 220px

, map_caption ...

in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

(Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

); surviving manuscripts from this era seem to preserve separate recensions of the text which diverged as early as the 2nd or 4th century. A passage in some of the recensions credits an Agathodaemon

An agathodaemon ( grc, ἀγαθοδαίμων, ) or agathos daemon (, , ) was a spirit ('' daemon'') of ancient Greek religion. They were personal or supernatural companion spirits, comparable to the Roman '' genii'', who ensured good luck, fer ...

with drafting a world map, but no maps seem to have survived to be used by Planude's monks. Instead, he commissioned new world maps calculated from Ptolemy's thousands of coordinates and drafted according to the text's 1st and 2nd projections, along with the equirectangular regional maps. A copy was translated into Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

by Jacobus Angelus at Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

around 1406 and soon supplemented with maps on the 1st projection. Maps using the 2nd projection were not made in Western Europe until Nicolaus Germanus's 1466 edition. Ptolemy's 3rd (and hardest) projection does not seem to have been used at all before new discoveries expanded the known world beyond the point where it provided a useful format.

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

's ''Dream of Scipio

A dream is a succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that usually occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep. Humans spend about two hours dreaming per night, and each dream lasts around 5 to 20 minutes, althou ...

'' described the Earth as a globe of insignificant size in comparison to the remainder of the cosmos. Many medieval manuscripts of Macrobius

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius, usually referred to as Macrobius (fl. AD 400), was a Roman provincial who lived during the early fifth century, during late antiquity, the period of time corresponding to the Later Roman Empire, and when Latin was ...

' ''Commentary on the Dream of Scipio'' include maps of the Earth, including the antipodes, zonal maps showing the Ptolemaic climates derived from the concept of a spherical Earth and a diagram showing the Earth (labeled as ''globus terrae'', the sphere of the Earth) at the center of the hierarchically ordered planetary spheres.

''Tabula Peutingeriana'' (4th century)

The ''Tabula Peutingeriana

' (Latin for "The Peutinger Map"), also referred to as Peutinger's Tabula or Peutinger Table, is an illustrated ' (ancient Roman road map) showing the layout of the '' cursus publicus'', the road network of the Roman Empire.

The map is a 13th-ce ...

'' (''Peutinger table'') is an itinerarium showing the ''cursus publicus

The ''cursus publicus'' (Latin: "the public way"; grc, δημόσιος δρόμος, ''dēmósios drómos'') was the state mandated and supervised courier and transportation service of the Roman Empire, later inherited by the Eastern Roma ...

'', the road network in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

. It is a 13th-century copy of an original map dating from the 4th century, covering Europe, parts of Asia (India) and North Africa. The map is named after Konrad Peutinger

Conrad Peutinger (14 October 1465 – 28 December 1547) was a German humanist, jurist, diplomat, politician, economist and archaeologist (serving as Emperor Maximilian I's chief archaeological adviser). A senior official in the municipal governme ...

, a German 15th–16th century humanist and antiquarian. The map was discovered in a library in Worms Worms may refer to:

*Worm, an invertebrate animal with a tube-like body and no limbs

Places

*Worms, Germany, a city

** Worms (electoral district)

* Worms, Nebraska, U.S.

*Worms im Veltlintal, the German name for Bormio, Italy

Arts and entertai ...

by Conrad Celtes

Conrad Celtes (german: Konrad Celtes; la, Conradus Celtis (Protucius); 1 February 1459 – 4 February 1508) was a German Renaissance humanist scholar and poet of the German Renaissance born in Franconia (nowadays part of Bavaria). He led the ...

, who was unable to publish his find before his death, and bequeathed the map in 1508 to Peutinger. It is conserved at the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Hofburg

The Hofburg is the former principal imperial palace of the Habsburg dynasty. Located in the centre of Vienna, it was built in the 13th century and expanded several times afterwards. It also served as the imperial winter residence, as Schönbru ...

, Vienna.

Middle Ages

Cosmas Indicopleustes' Map (6th century)

Around 550

Around 550 Cosmas Indicopleustes

Cosmas Indicopleustes ( grc-x-koine, Κοσμᾶς Ἰνδικοπλεύστης, lit=Cosmas who sailed to India; also known as Cosmas the Monk) was a Greek merchant and later hermit from Alexandria of Egypt. He was a 6th-century traveller who ma ...

wrote the copiously illustrated ''Christian Topography

The ''Christian Topography'' ( grc, Χριστιανικὴ Τοπογραφία, la, Topographia Christiana) is a 6th-century work, one of the earliest essays in scientific geography written by a Christian author. It originally consisted of fiv ...

'', a work partly based on his personal experiences as a merchant on the Red Sea and Indian Ocean in the early 6th century. Though his cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony refers to the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used i ...

is refuted by modern science, he has given a historic description of India and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

during the 6th century, which is invaluable to historians. Cosmas seems to have personally visited the Kingdom of Axum

Axum, or Aksum (pronounced: ), is a town in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia with a population of 66,900 residents (as of 2015).

It is the site of the historic capital of the Aksumite Empire, a naval and trading power that ruled the whole region ...

in modern Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the Er ...

and Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

, as well as India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

. In 522 CE, he visited the Malabar Coast

The Malabar Coast is the southwestern coast of the Indian subcontinent. Geographically, it comprises the wettest regions of southern India, as the Western Ghats intercept the moisture-laden monsoon rains, especially on their westward-facing ...

(South India). A major feature of his ''Topography'' is Cosmas' worldview that the world

In its most general sense, the term "world" refers to the totality of entities, to the whole of reality or to everything that is. The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the worl ...

is flat, and that the heavens form the shape of a box with a curved lid, a view he took from unconventional interpretations of Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pract ...

. Cosmas aimed to prove that pre-Christian geographers had been wrong in asserting that the earth was spherical and that it was in fact modelled on the Tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle ( he, מִשְׁכַּן, mīškān, residence, dwelling place), also known as the Tent of the Congregation ( he, link=no, אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד, ’ōhel mō‘ēḏ, also Tent of Meeting, etc.), ...

, the house of worship described to Moses by God during the Jewish Exodus from Egypt.

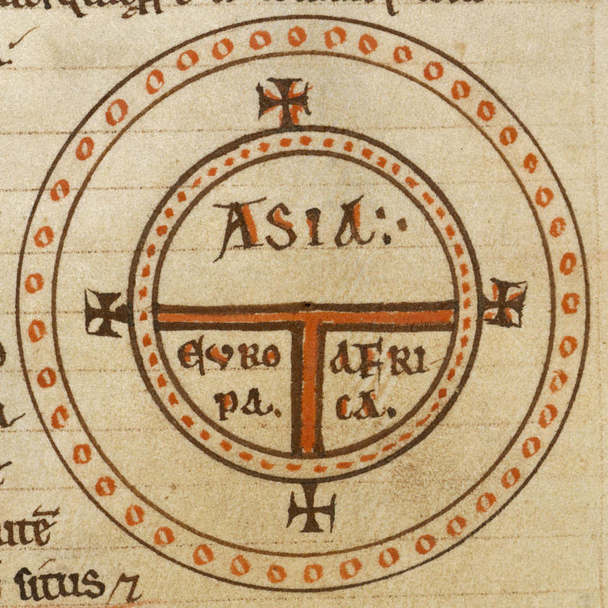

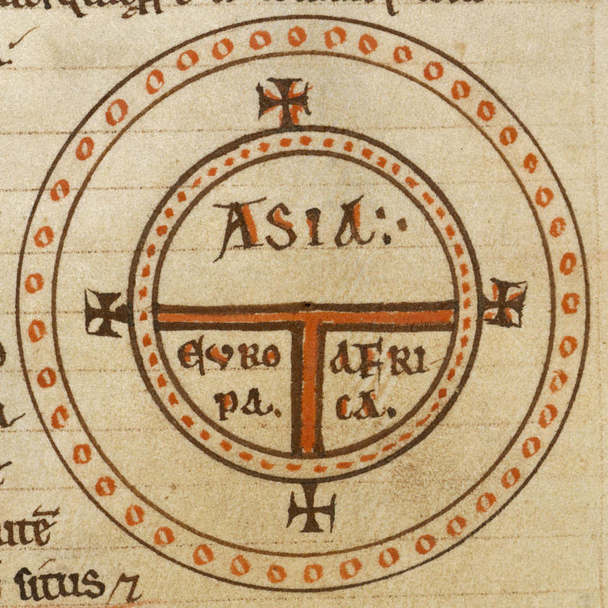

Isidore of Sevilla's ''T and O map'' (c. 636)

The medievalT and O map

A T and O map or O–T or T–O map (''orbis terrarum'', orb or circle of the lands; with the letter T inside an O), also known as an Isidoran map, is a type of early world map that represents the physical world as first described by the 7th-ce ...

s originate with the description of the world in the ''Etymologiae

''Etymologiae'' (Latin for "The Etymologies"), also known as the ''Origines'' ("Origins") and usually abbreviated ''Orig.'', is an etymological encyclopedia compiled by Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636) towards the end of his life. Isidore was ...

'' of Isidore of Seville (died 636). This qualitative and conceptual type of medieval cartography

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an ...

represents only the top-half of a spherical Earth. It was presumably tacitly considered a convenient projection of the inhabited portion of the world known in Roman and Medieval times (that is, the northern temperate half of the globe). The ''T'' is the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

, dividing the three continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

s, Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

, Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and the ''O'' is the surrounding Ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

. Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

was generally represented in the center of the map. Asia was typically the size of the other two continents combined. Because the sun rose in the east, Paradise (the Garden of Eden) was generally depicted as being in Asia, and Asia was situated at the top portion of the map.

Albi Mappa Mundi (8th century)

The Albi Mappa Mundi is a medieval map of the world, included in a manuscript of the second half of the 8th century, preserved in the old collection of the library Pierre-Amalric in

The Albi Mappa Mundi is a medieval map of the world, included in a manuscript of the second half of the 8th century, preserved in the old collection of the library Pierre-Amalric in Albi

Albi (; oc, Albi ) is a commune in France, commune in southern France. It is the prefecture of the Tarn (department), Tarn Departments of France, department, on the river Tarn (river), Tarn, 85 km northeast of Toulouse. Its inhabitants ar ...

, France. This manuscript comes from the chapter library of the Sainte-Cécile Albi Cathedral

The Cathedral Basilica of Saint Cecilia (French: ''Basilique Cathédrale Sainte-Cécile d'Albi''), also known as Albi Cathedral, is the seat of the Catholic Archbishop of Albi. First built in the aftermath of the Albigensian Crusade, the grim e ...

. The Albi Mappa Mundi was inscribed in October 2015 in the Memory of the World Programme

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembered, ...

of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. I ...

.

The manuscript bearing the card contains 77 pages. It is named in the eighteenth century "''Miscellanea''" (Latin word meaning "collection"). This collection contains 22 different documents, which had educational functions. The manuscript, a Parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves, and goats. It has been used as a writing medium for over two millennia. Vellum is a finer quality parchment made from the skins o ...

probably made from a goat or sheep skin, is in a very good state of preservation.

The map itself is 27 cm high by 22.5 wide. It represents 23 countries on 3 continents and mentions several cities, islands, rivers and seas. The known world is represented in the form of a horseshoe, opening at the level of the Strait of Gibraltar, and surrounding the Mediterranean, with the Middle East at the top, Europe on the left and North Africa on the right.

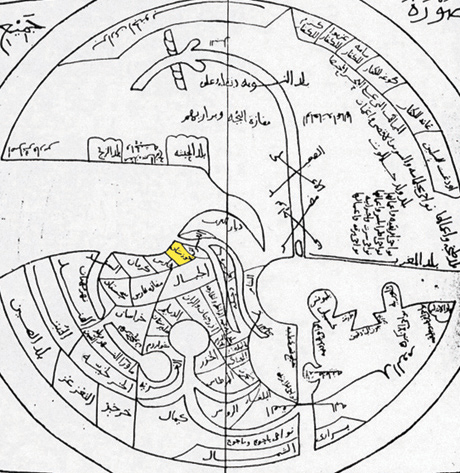

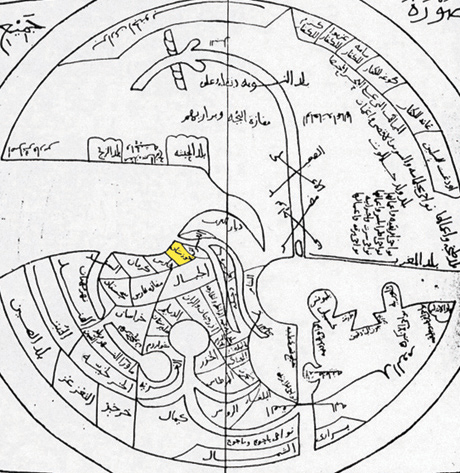

Ibn Hawqal's map (10th century)

Ibn Hawqal

Muḥammad Abū’l-Qāsim Ibn Ḥawqal (), also known as Abū al-Qāsim b. ʻAlī Ibn Ḥawqal al-Naṣībī, born in Nisibis, Upper Mesopotamia; was a 10th-century Arab Muslim writer, geographer, and chronicler who travelled during the y ...

was an Arab scientist of the 10th century who developed a world map, based on his own travel experience and probably the works of Ptolemy. Another such cartographer was Istakhri.

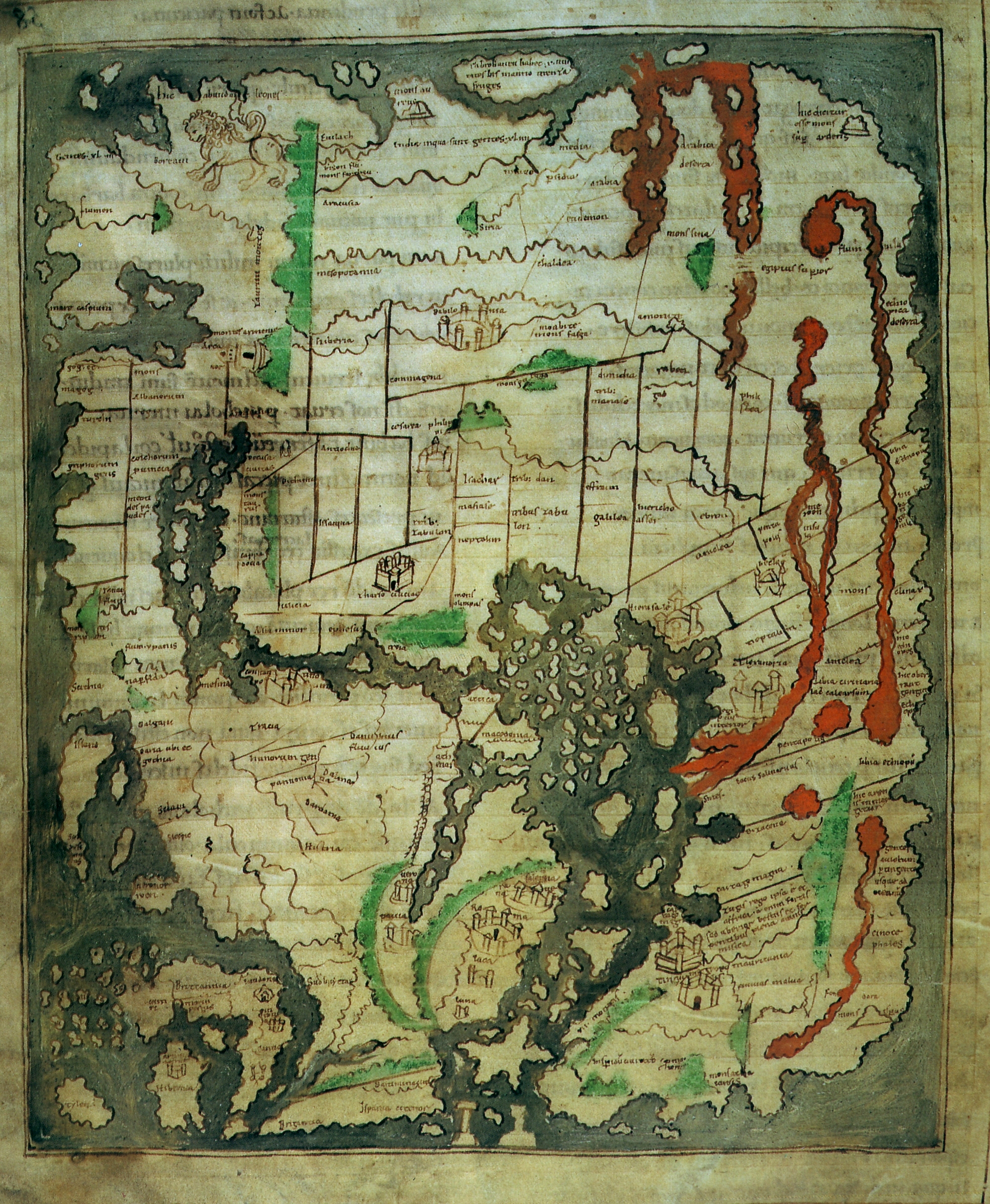

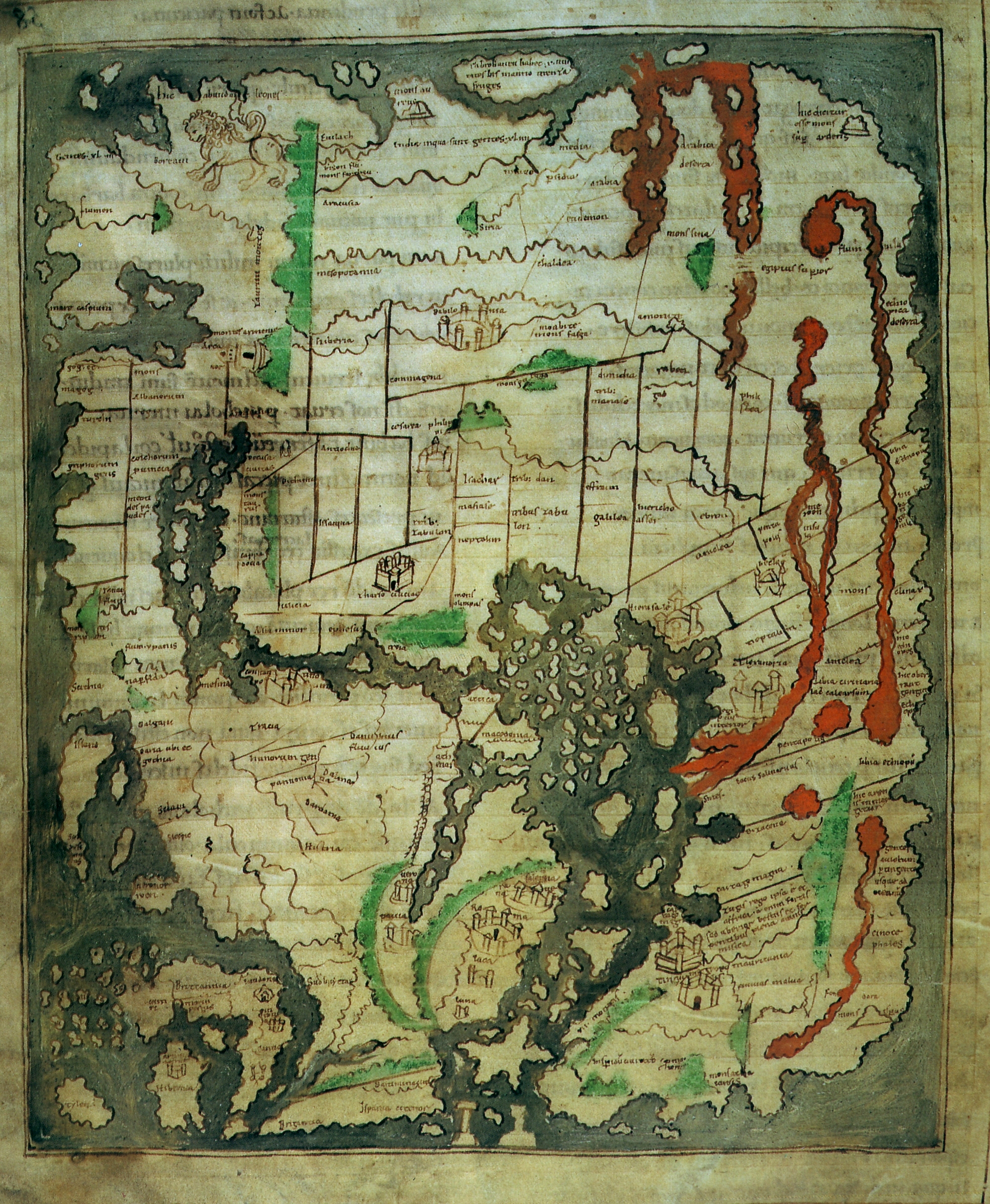

Anglo-Saxon ''Cotton'' World Map (c. 1040)

This map appears in a copy of a classical work on geography, the Latin version by

This map appears in a copy of a classical work on geography, the Latin version by Priscian

Priscianus Caesariensis (), commonly known as Priscian ( or ), was a Latin grammarian and the author of the ''Institutes of Grammar'', which was the standard textbook for the study of Latin during the Middle Ages. It also provided the raw materia ...

of the ''Periegesis'', that was among the manuscripts in the Cotton library

The Cotton or Cottonian library is a collection of manuscripts once owned by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton MP (1571–1631), an antiquarian and bibliophile. It later became the basis of what is now the British Library, which still holds the collecti ...

( MS. Tiberius B.V., fol. 56v), now in the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the Briti ...

. It is no