early life of Woodrow Wilson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1883, Wilson met and fell in love with Ellen Louise Axson, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister from

In 1883, Wilson met and fell in love with Ellen Louise Axson, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister from

In June 1902, Princeton trustees promoted Professor Wilson to president, replacing Patton, whom the trustees perceived to be an inefficient administrator. Wilson aspired, as he told alumni, "to transform thoughtless boys performing tasks into thinking men." He tried to raise admission standards and to replace the "gentleman's C" with serious study. To emphasize the development of expertise, Wilson instituted academic departments and a system of core requirements. Students were to meet in groups of six under the guidance of teaching assistants known as preceptors. To fund these new programs, Wilson undertook an ambitious and successful fundraising campaign, convincing alumni such as

In June 1902, Princeton trustees promoted Professor Wilson to president, replacing Patton, whom the trustees perceived to be an inefficient administrator. Wilson aspired, as he told alumni, "to transform thoughtless boys performing tasks into thinking men." He tried to raise admission standards and to replace the "gentleman's C" with serious study. To emphasize the development of expertise, Wilson instituted academic departments and a system of core requirements. Students were to meet in groups of six under the guidance of teaching assistants known as preceptors. To fund these new programs, Wilson undertook an ambitious and successful fundraising campaign, convincing alumni such as

Wilson became disenchanted with his job due to the resistance to his recommendations, and he began considering a run for office. Prior to the

Wilson became disenchanted with his job due to the resistance to his recommendations, and he began considering a run for office. Prior to the

''Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics.''

Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1885.

''The State: Elements of Historical and Practical Politics.''

Boston: D.C. Heath, 1889.

''Division and Reunion, 1829–1889.''

New York, London, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1893.

Old Master and Other Political Essays.''

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1893.

''Mere Literature and Other Essays.''

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1896.

''George Washington.''

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1897. * ''The History of the American People.'' In five volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1901–02.Vol. 1

Vol. 2

Vol. 3

Vol. 4

Vol. 5

/small>

''Constitutional Government in the United States.''

New York: Columbia University Press, 1908.

''The Free Life: A Baccalaureate Address.''

New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1908.

''The New Freedom: A Call for the Emancipation of the Energies of a Generous People.''

New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1913. —Speeches

''The Road Away from Revolution.''

Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1923. * ''The Public Papers of Woodrow Wilson.'' Ray Stannard Baker and William E. Dodd (eds.) In six volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1925–27. * ''Study of public administration'' (Washington:

Thomas Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

(December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

. The early life of Woodrow Wilson covers the time period from his birth in late 1856 through his entry into electoral politics in 1910. Wilson spent his early years in the American South, mainly in Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navigable portion. Georgi ...

, during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. After earning a Ph.D. in political science from Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

, Wilson taught at various schools before becoming the president of Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

. Wilson later went onto become governor of New Jersey

The governor of New Jersey is the head of government of New Jersey. The office of governor is an elected position with a four-year term. There is a two consecutive term term limit, with no limitation on non-consecutive terms. The official r ...

from 1911 to 1913, a major progressive reformer and then finally, President of the United States from 1913 to 1921.

Early life

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was born to a family of Scots-Irish and Scottish descent, in Staunton, Virginia. He was the third of four children and the first son ofJoseph Ruggles Wilson

Joseph Ruggles Wilson Sr. (February 28, 1822 – January 21, 1903) was a prominent Presbyterian theologian and father of President Woodrow Wilson, ''Nashville Banner'' editor Joseph Ruggles Wilson Jr., and Anne E. Wilson Howe. In 1861, as pastor o ...

(1822–1903) and Jessie Janet Woodrow (1826–1888). Wilson's paternal grandparents had immigrated to the United States from Strabane, County Tyrone

County Tyrone (; ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the thirty-two traditional counties of Ireland. It is no longer used as an administrative division for local government but retai ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

in 1807, settling in Steubenville, Ohio

Steubenville is a city in and the county seat of Jefferson County, Ohio, United States. Located along the Ohio River 33 miles west of Pittsburgh, it had a population of 18,161 at the 2020 census. The city's name is derived from Fort Steuben, a ...

. His grandfather James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

*James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Quebe ...

published a pro-tariff and anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

newspaper, ''The Western Herald and Gazette''. Wilson's maternal grandfather, Reverend Thomas Woodrow, migrated from Paisley, Scotland to Carlisle, England, before moving to Chillicothe, Ohio in the late 1830s. Joseph met Jessie while she was attending a girl's academy in Steubenville, and the two married on June 7, 1849. Soon after the wedding, Joseph was ordained as a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

pastor and assigned to serve in Staunton. Thomas was born in The Manse, a house of the Staunton First Presbyterian Church where Joseph served. Wilson's parents gave him the nickname "Tommy", which he used through his undergraduate college years. Before he was two, the family moved to Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navigable portion. Georgi ...

. Wilson grew up in a home where slave labor was utilized.

Wilson's earliest memory was of playing in his yard and standing near the front gate of the Augusta parsonage at the age of three, when he heard a passerby announce in disgust that Abraham Lincoln had been elected and that a war was coming. By 1861, both of Wilson's parents had come to fully identify with the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

and they supported the Confederacy during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. Wilson's father was one of the founders of the Southern Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) after it split from the Northern Presbyterians in 1861. He became minister of the First Presbyterian Church in Augusta, and the family lived there until 1870.

After the end of the Civil War, Wilson began attending a nearby school, where classmates included future Supreme Court Justice Joseph Rucker Lamar

Joseph Rucker Lamar (October 14, 1857 – January 2, 1916) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court appointed by President William Howard Taft. A cousin of former associate justice Lucius Lamar, he served from 1911 until hi ...

and future ambassador to Switzerland Pleasant A. Stovall. Though Wilson's parents placed a high value on education, he struggled with reading and writing until the age of thirteen, possibly because of developmental dyslexia. From 1870 to 1874, Wilson lived in Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia is the List of capitals in the United States, capital of the U.S. state of South Carolina. With a population of 136,632 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is List of municipalities in South Carolina, the second-largest ...

, where his father was a theology professor at the Columbia Theological Seminary

Columbia Theological Seminary is a Presbyterian seminary in Decatur, Georgia. It is one of ten theological institutions affiliated with the Presbyterian Church (USA).

History

Columbia Theological Seminary was founded in 1828 in Lexington, Geor ...

. In 1873, Wilson became a communicant member of the Columbia First Presbyterian Church; he remained a member throughout his life.

Wilson attended Davidson College in North Carolina for the 1873–74 school year, but transferred as a freshman to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

). He studied political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, ...

and history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

, joined the Phi Kappa Psi

Phi Kappa Psi (), commonly known as Phi Psi, is an American collegiate social fraternity that was founded by William Henry Letterman and Charles Page Thomas Moore in Widow Letterman's home on the campus of Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pen ...

fraternity, was active in the Whig literary and debating society, and organized the Liberal Debating Society. He was also elected secretary of the school's football association, president of the school's baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

association, and managing editor of the student newspaper. In the hotly contested presidential election of 1876, Wilson declared his support for the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

and its nominee, Samuel J. Tilden. Influenced by the work of Walter Bagehot

Walter Bagehot ( ; 3 February 1826 – 24 March 1877) was an English journalist, businessman, and essayist, who wrote extensively about government, economics, literature and race. He is known for co-founding the ''National Review'' in 1855 ...

, as well as the declining power of the presidency in the aftermath of the Civil War, Wilson developed a plan to reform American government along the lines of the British parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of th ...

. Political scientist George W. Ruiz writes that Wilson's "admiration for the parliamentary style of government, and the desire to adapt some of its features to the American system, remained an enduring element of Woodrow Wilson's political thought." Wilson's essay on governmental reform was published in the ''International Review'' after winning the approval of editor Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

.Berg (2013), pp. 70–72

After graduating from Princeton in 1879, Wilson attended the University of Virginia School of Law, where he was involved in the Virginia Glee Club

The Virginia Glee Club is a men's chorus based at the University of Virginia. It performs both traditional and contemporary vocal works typically in TTBB arrangements. Founded in 1871, the Glee Club is the university's oldest musical organization ...

and served as president of the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society

The Jefferson Literary and Debating Society (commonly known "Jeff Soc") is the oldest continuously existing collegiate debating society in North America, having been founded on July 14, 1825, in Room Seven, West Lawn. Named after founder of the U ...

. After poor health forced his withdrawal from the University of Virginia, Wilson continued to study law on his own while living with his parents in Wilmington, North Carolina

Wilmington is a port city in and the county seat of New Hanover County in coastal southeastern North Carolina, United States.

With a population of 115,451 at the 2020 census, it is the eighth most populous city in the state. Wilmington is t ...

.

Wilson was admitted to the Georgia bar

The State Bar of Georgia is the governing body of the legal profession in the State of Georgia, operating under the supervision of the Supreme Court of Georgia. Membership is a condition of admission to practice law in Georgia.

The State Bar w ...

and made a brief attempt at establishing a legal practice

Legal practice is sometimes used to distinguish the body of judicial or administrative precedents, rules, policies, customs, and doctrines from legislative enactments such as statutes and constitutions which might be called "laws" in the strict ...

in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

in 1882. Though he found legal history and substantive jurisprudence interesting, he abhorred the day-to-day procedural aspects. After less than a year, he abandoned his legal practice to pursue the study of political science and history.

Personal life

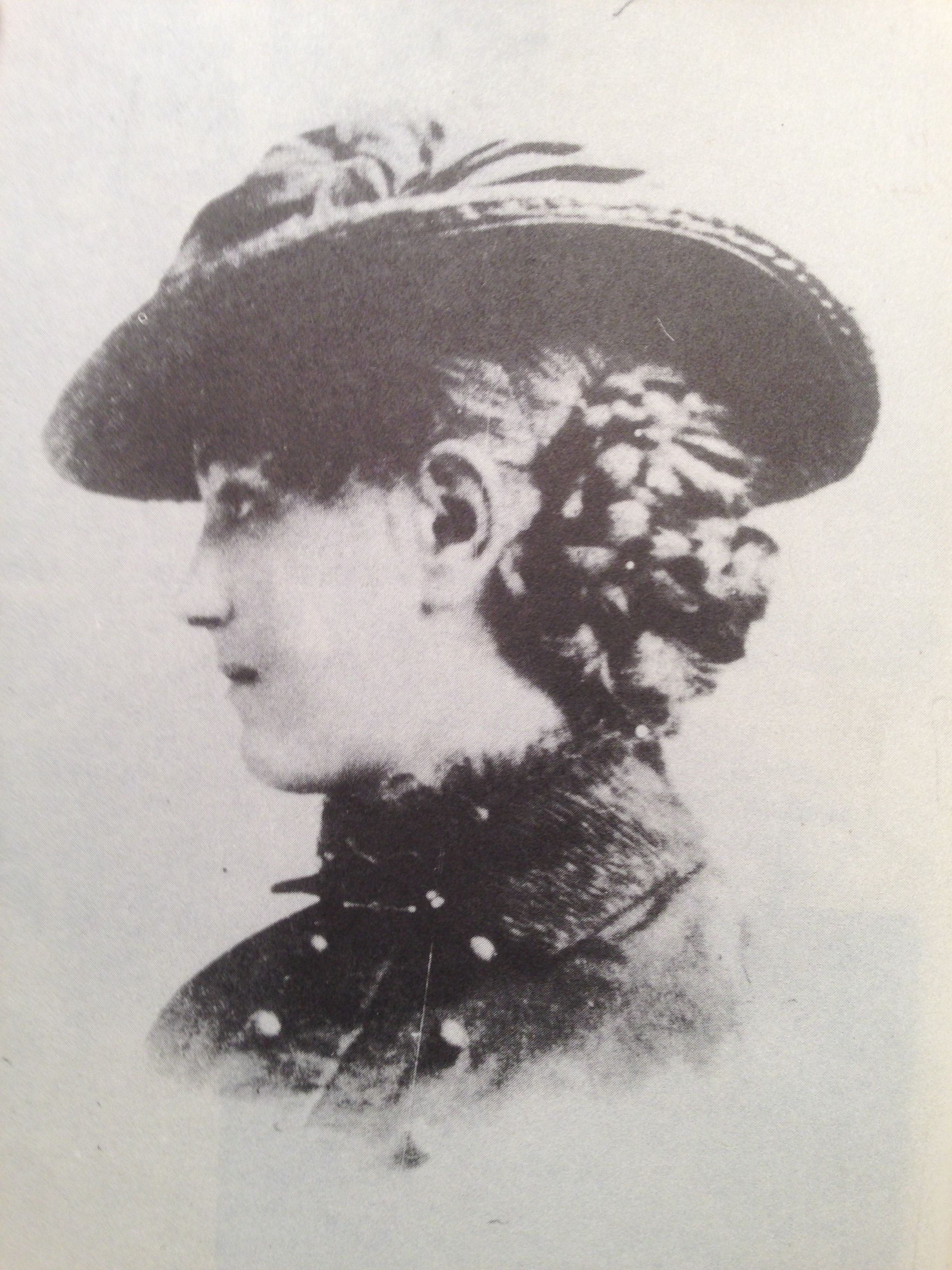

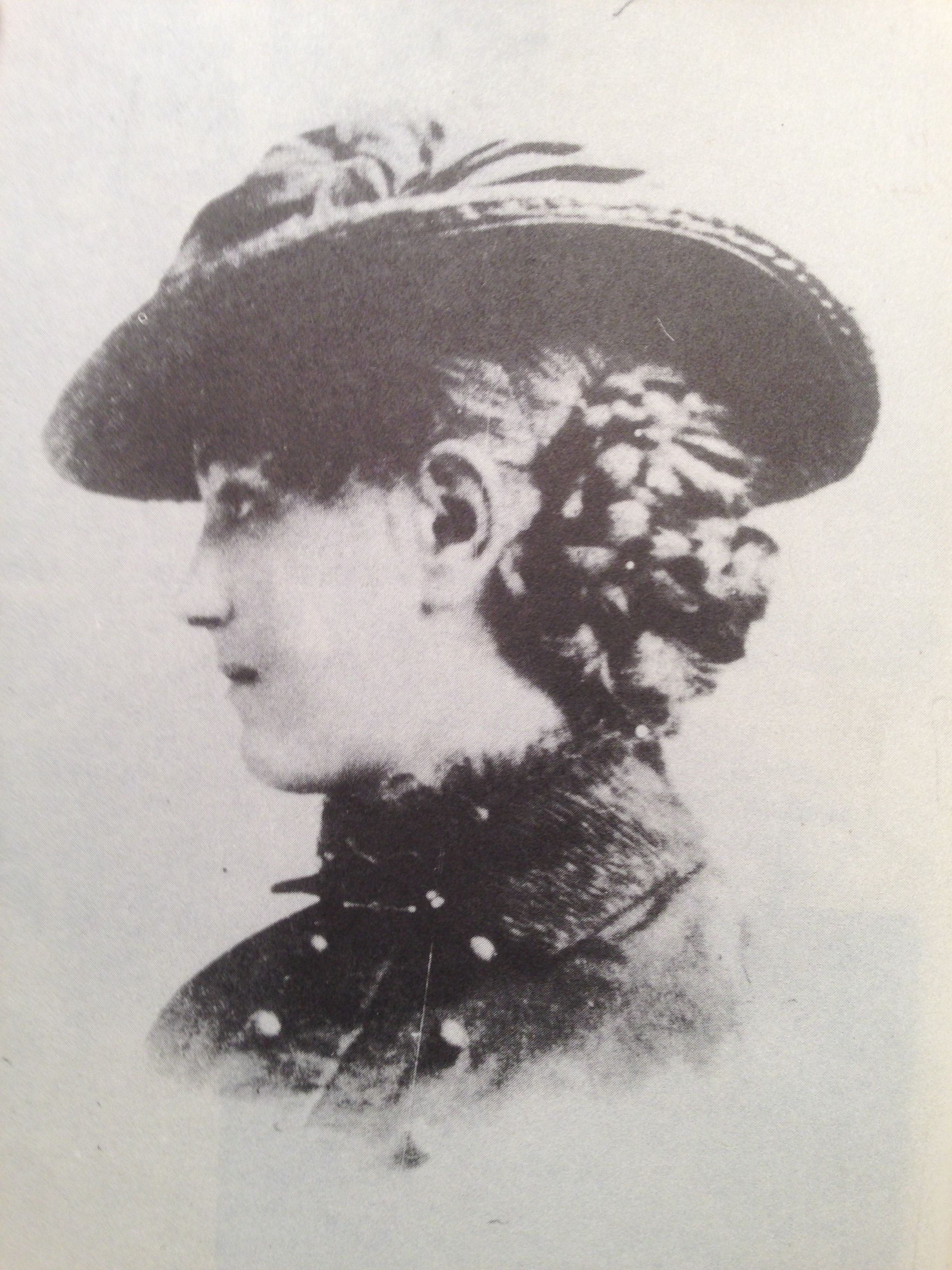

In 1883, Wilson met and fell in love with Ellen Louise Axson, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister from

In 1883, Wilson met and fell in love with Ellen Louise Axson, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister from Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the British colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later t ...

. He proposed marriage in September 1883; she accepted, but they agreed to postpone marriage while Wilson attended graduate school. Wilson's marriage to Ellen was complicated by traumatic developments in her family; in late 1883, Ellen's father Edward, suffering from depression, was admitted to the Georgia State Mental Hospital where, in 1884, he committed suicide. After recovering from the initial shock, Ellen gained admission to the Art Students League of New York. After graduation, she pursued portrait art and received a medal for one of her works from the Paris International Exposition. She happily agreed to sacrifice further independent artistic pursuits in order to keep her marriage commitment, and in 1885 she and Wilson married. She strongly supported his career and learned German so that she could help translate works of political science that were relevant to Wilson's research.

Their first child, Margaret, was born in April 1886, and their second child, Jessie, was born in August 1887. Their third and final child, Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was introd ...

, was born in October 1889. Wilson and his family lived in a seven bedroom Tudor Revival

Tudor Revival architecture (also known as mock Tudor in the UK) first manifested itself in domestic architecture in the United Kingdom in the latter half of the 19th century. Based on revival of aspects that were perceived as Tudor architecture ...

house near Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

from 1896 to 1902, when they moved to Prospect House on Princeton's campus. In 1913, Jessie married Francis Bowes Sayre Sr., who later served as High Commissioner to the Philippines

The high commissioner to the Philippines was the personal representative of the president of the United States to the Commonwealth of the Philippines during the period 1935–1946. The office was created by the Tydings–McDuffie Act of 1 ...

. In 1914, Eleanor married William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

, who served as the Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

under Wilson and later represented California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

.Berg (2013), p. 328

When Wilson began vacationing in Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

in 1906, he met a socialite, Mary Hulbert Peck. Their visits together became a regular occurrence on his return. Wilson in his letters home to Ellen openly related these gatherings as well his other social events. According to biographer August Heckscher, Wilson's friendship with Peck became the topic of frank discussion between Wilson and his wife. Wilson historians have not conclusively established there was an affair; but Wilson did on one occasion write a musing in shorthand—on the reverse side of a draft for an editorial: "my precious one, my beloved Mary." Wilson also sent very personal letters to her which would later be used against him by his adversaries.

Ellen died from Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied ...

in August 1914, the second year of Wilson's presidency.

Following the death of his first wife, Wilson met and began a courtship with Edith Bolling Galt; the two married in a quiet ceremony at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

in December 1915.

Academic career

Professor

In late 1883, Wilson enteredJohns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

, a new graduate institution in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

modeled after German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

universities. In order to successfully complete his Ph.D.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

, Wilson studied the German language

German ( ) is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is als ...

extensively. At times Wilson referenced German sources, both as an academic and during the lead up to America's entry into World War I; though he noted doing so took considerable time and effort as he was not fully fluent.Pestritto (2005), 34. Wilson hoped to become a professor, writing that "a professorship was the only feasible place for me, the only place that would afford leisure for reading and for original work, the only strictly literary berth with an income attached." During his time at Johns Hopkins, Wilson took courses by eminent scholars such as Herbert Baxter Adams

Herbert Baxter Adams (April 16, 1850 – July 30, 1901) was an American educator and historian who brought German rigor to the study of history in America; a founding member of the American History Association; and one of the earliest ed ...

, Richard T. Ely

Richard Theodore Ely (April 13, 1854 – October 4, 1943) was an American economist, author, and leader of the Progressive movement who called for more government intervention to reform what they perceived as the injustices of capitalism, especial ...

, and J. Franklin Jameson. Wilson spent much of his time at Johns Hopkins writing ''Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics'', which grew out of a series of essays in which he examined the workings of the federal government. He received a Ph.D. in history of government from Johns Hopkins in 1886.

In early 1885, Houghton Mifflin

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , ''asteriskos'', "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often voc ...

published ''Congressional Government'', which received a strong reception; one critic called it "the best critical writing on the American constitution which has appeared since the '' Federalist Papers''." That same year, Wilson accepted a teaching position at Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College ( ; Welsh: ) is a women's liberal arts college in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Founded as a Quaker institution in 1885, Bryn Mawr is one of the Seven Sister colleges, a group of elite, historically women's colleges in the United ...

, a newly established women's college

Women's colleges in higher education are undergraduate, bachelor's degree-granting institutions, often liberal arts colleges, whose student populations are composed exclusively or almost exclusively of women. Some women's colleges admit male stud ...

on the Philadelphia Main Line

The Philadelphia Main Line, known simply as the Main Line, is an informally delineated historical and social region of suburban Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Lying along the former Pennsylvania Railroad's once prestigious Main Line, it runs ...

. Wilson taught at Bryn Mawr College from 1885 until 1888. He taught ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

and Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

history, American history, political science, and other subjects. He sought to inspire "genuine living interest in the subjects of study" and asked students to "look into ancient times as if they were our own times." In 1888, Wilson left Bryn Mawr for Wesleyan University

Wesleyan University ( ) is a private liberal arts university in Middletown, Connecticut. Founded in 1831 as a men's college under the auspices of the Methodist Episcopal Church and with the support of prominent residents of Middletown, the col ...

in Middletown, Connecticut. At Wesleyan he coached the football team, founded a debate team, and taught graduate courses in political economy and Western history

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

.

In February 1890, with the help of friends, Wilson was elected by the Princeton University Board of Trustees to the Chair of Jurisprudence and Political Economy, at an annual salary of $3,000 (). He quickly gained a reputation as a compelling speaker; one student described him as "the greatest class-room lecturer I ever have heard." During his time as a professor at Princeton, he also delivered a series of lectures at Johns Hopkins, New York Law School

New York Law School (NYLS) is a private law school in Tribeca, New York City. NYLS has a full-time day program and a part-time evening program. NYLS's faculty includes 54 full-time and 59 adjunct professors. Notable faculty members include E ...

, and Colorado College

Colorado College is a private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Colorado Springs, Colorado. It was founded in 1874 by Thomas Nelson Haskell in his daughter's memory. The college enrolls approxi ...

.Berg (2013), pp. 121–122 In 1896, Francis Landey Patton announced that Princeton would henceforth officially be known as Princeton University instead of the College of New Jersey, and he unveiled an ambitious program of expansion that included the establishment of a graduate school. In the 1896 presidential election, Wilson rejected Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

and supported the conservative "Gold Democrat

The National Democratic Party, also known as Gold Democrats, was a short-lived political party of Bourbon Democrats who opposed the regular party nominee William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 presidential election. The party was then a "liberal" p ...

" nominee, John M. Palmer. Wilson's academic reputation continued to grow throughout the 1890s, and he turned down positions at Johns Hopkins, the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

, and other schools because he wanted to remain at Princeton.

Friendship with Thomas Dixon Jr

It was during his early years as a student at Johns Hopkins that Wilson met and befriended classmate and fellow Southerner,Thomas Dixon Jr

Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. (January 11, 1864 – April 3, 1946) was an American white supremacist, Baptist minister, politician, lawyer, lecturer, novelist, playwright, and filmmaker. Referred to as a "professional racist", Dixon wrote two best- ...

.Dixon Jr., Thomas (1984). Crowe, Karen (ed.). Southern Horizons: The Autobiography of Thomas Dixon. Alexandria, Virginia: IWV Publishing. OCLC 11398740. Dixon says in his memoirs that "we became intimate friends.... I spent many hours with him in ilson's room" Dixon stayed at Johns Hopkins for only one semester before dropping out to pursue career on the stage. Wilson objected to Dixon's decision but the two remained friends. Though Dixon found great popular and financial success as both a writer and evangelical preaching, he is now known primarily as one of the time's most prolific promoters of white supremacy, being described as a "professional racist". In 1888, Dixon was asked to give the commencement address at Wake Forest University

Wake Forest University is a private research university in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Founded in 1834, the university received its name from its original location in Wake Forest, north of Raleigh, North Carolina. The Reynolda Campus, the un ...

. Dixon, replied by politely turning down the offer, recommending Wilson be chosen instead. Dixon, spoke in incredibly high terms of the then generally obscure Wilson. A reporter at Wake Forest who heard Dixon's praises of Wilson put a story on the nation wire, giving Wilson his first national exposure. In 1915, when one of Dixon's books was made into a feature film, ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'', originally called ''The Clansman'', is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play ''The Clan ...

'', Dixon asked Wilson to screen the film at the White House, a request Wilson was happy to oblige for his old friend. The extremely racist nature of the film sparked great controversy as did Wilson's personal ties to Dixon; eventually Wilson reluctantly renounced the message of ''The Birth of a Nation''.

Author

During his academic career, Wilson authored several works of history and political science and became a regular contributor to ''Political Science Quarterly

''Political Science Quarterly'' is an American double blind peer-reviewed academic journal covering government, politics, and policy, published since 1886 by the Academy of Political Science. Its editor-in-chief is Robert Y. Shapiro (Columbia U ...

'', an academic journal. Wilson's first political work, ''Congressional Government'' (1885), critically described the U.S. system of government and advocated adopting reforms to move the U.S. closer to a parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of th ...

. Wilson believed the Constitution had a "radical defect" because it did not establish a branch of government that could "decide at once and with conclusive authority what shall be done." He singled out the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

for particular criticism, writing,

Wilson's second publication was a textbook, entitled ''The State'', that was used widely in college courses throughout the country until the 1920s. In ''The State'', Wilson wrote that governments could legitimately promote the general welfare "by forbidding child labor, by supervising the sanitary conditions of factories, by limiting the employment of women in occupations hurtful to their health, by instituting official tests of the purity or the quality of goods sold, by limiting the hours of labor in certain trades, ndby a hundred and one limitations of the power of unscrupulous or heartless men to out-do the scrupulous and merciful in trade or industry." He also wrote that charity efforts should be removed from the private domain and "made the imperative legal duty of the whole," a position which, according to historian Robert M. Saunders, seemed to indicate that Wilson "was laying the groundwork for the modern welfare state."

His third book, entitled ''Division and Reunion'', was published in 1893. It became a standard university textbook for teaching mid- and late-19th century U.S. history. In 1897, Houghton Mifflin published Wilson's biography on George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

; Berg describes it as "Wilson's poorest literary effort." Wilson's fourth major publication, a five-volume work entitled ''History of the American People'', was the culmination of a series of articles written for '' Harper's'', and was published in 1902. In 1908, Wilson published his last major scholarly work, ''Constitutional Government of the United States''.

President of Princeton University

In June 1902, Princeton trustees promoted Professor Wilson to president, replacing Patton, whom the trustees perceived to be an inefficient administrator. Wilson aspired, as he told alumni, "to transform thoughtless boys performing tasks into thinking men." He tried to raise admission standards and to replace the "gentleman's C" with serious study. To emphasize the development of expertise, Wilson instituted academic departments and a system of core requirements. Students were to meet in groups of six under the guidance of teaching assistants known as preceptors. To fund these new programs, Wilson undertook an ambitious and successful fundraising campaign, convincing alumni such as

In June 1902, Princeton trustees promoted Professor Wilson to president, replacing Patton, whom the trustees perceived to be an inefficient administrator. Wilson aspired, as he told alumni, "to transform thoughtless boys performing tasks into thinking men." He tried to raise admission standards and to replace the "gentleman's C" with serious study. To emphasize the development of expertise, Wilson instituted academic departments and a system of core requirements. Students were to meet in groups of six under the guidance of teaching assistants known as preceptors. To fund these new programs, Wilson undertook an ambitious and successful fundraising campaign, convincing alumni such as Moses Taylor Pyne

Moses Taylor Pyne (December 21, 1855 – April 22, 1921), was an American financier and philanthropist, and one of Princeton University's greatest benefactors and its most influential trustee.

Biography

The son of Percy Rivington Pyne (182 ...

and philanthropists such as Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

to donate to the school.

Wilson appointed the first Jew and the first Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

to the Princeton faculty, and is credited with helping to liberate the board from domination by conservative Presbyterians. However, Wilson also worked to keep African Americans out of the school, even as other Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight school ...

schools were accepting small numbers of blacks. Wilson invited only one African-American guest (out of an estimated 150) to attend his installation ceremony, Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

. Though most accounts agree Wilson respected Washington, he would not allow for him to be housed on campus with a member of the faculty (such arrangements had been made for all of the white guests coming from out of town to attend the ceremony) nor did Wilson invite Washington to either of the two dinner parties hosted by him and his wife following the event. Under Wilson, campus facilities remained segregated, and no African-Americans were hired as faculty or admitted as undergraduate students during his tenure. In 1909, Wilson received a letter from a young African-American man interested in applying to attend Princeton, Wilson had his assistant write back promptly that "it is altogether inadvisable for a colored man to enter Princeton."Gestle, 107 Princeton would not receive a single black student until 1947. In 1903, while speaking before a Princeton alumni group in Baltimore, Wilson made a joke at the expense of William Crum, the recently appointed African-American customs officer for the port of Charleston

The Port of Charleston is a seaport located in South Carolina in the Southeastern United States. The port's facilities span three municipalities — Charleston, North Charleston, and Mount Pleasant — with six public terminals owned and operate ...

. Like many white Southerners, Wilson opposed Crum's appointment and in the course of his address referred to him as a "coon."

Wilson's efforts to reform Princeton earned him national notoriety, but they also took a toll on his health. In 1906, Wilson awoke to find himself blind in the left eye, the result of a blood clot and hypertension. Modern medical opinion surmises Wilson had suffered a stroke—he later was diagnosed, as his father had been, with hardening of the arteries. He began to exhibit his father's traits of impatience and intolerance, which would on occasion lead to errors of judgment.

Having reorganized the school's curriculum and established the preceptorial system, Wilson next attempted to curtail the influence of social elites at Princeton by abolishing the upper-class eating club

A dining club (UK) or eating club (US) is a social group, usually requiring membership (which may, or may not be available only to certain people), which meets for dinners and discussion on a regular basis. They may also often have guest speakers. ...

s. He proposed moving the students into colleges, also known as quadrangles, but Wilson's Quad Plan was met with fierce opposition from Princeton's alumni. In October 1907, due to the intensity of alumni opposition, the Board of Trustees instructed Wilson to withdraw the Quad Plan. Late in his tenure, Wilson had a confrontation with Andrew Fleming West, dean of the graduate school, and also West's ally ex-President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

, who was a trustee. Wilson wanted to integrate a proposed graduate school building into the campus core, while West preferred a more distant campus site. In 1909, Princeton's board accepted a gift made to the graduate school campaign subject to the graduate school being located off campus.

Entry into politics (1910)

Wilson became disenchanted with his job due to the resistance to his recommendations, and he began considering a run for office. Prior to the

Wilson became disenchanted with his job due to the resistance to his recommendations, and he began considering a run for office. Prior to the 1908 Democratic National Convention

The 1908 Democratic National Convention took place from July 7 to July 10, 1908, at Ellie Caulkins Opera House, Denver Auditorium Arena in Denver, Colorado.

The event is widely considered a significant part of Denver's political and social hist ...

, Wilson dropped hints to some influential players in the Democratic Party of his interest in the ticket. While he had no real expectations of being placed on the ticket, he left instructions that he should not be offered the vice presidential nomination. Party regulars considered his ideas politically as well as geographically detached and fanciful, but the seeds had been sown. McGeorge Bundy in 1956 described Wilson's contribution to Princeton: "Wilson was right in his conviction that Princeton must be more than a wonderfully pleasant and decent home for nice young men; it has been more ever since his time".

By January 1910, Wilson had drawn the attention of James Smith Jr. and George Brinton McClellan Harvey, two leaders of New Jersey's Democratic Party, as a potential candidate in the upcoming gubernatorial election

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

. Having lost the last five gubernatorial elections, New Jersey Democratic leaders decided to throw their support behind Wilson, an untested and unconventional candidate. Party leaders believed that Wilson's academic reputation made him the ideal spokesman against trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the "settl ...

and corruption, but they also hoped his inexperience in governing would make him easy to influence. Wilson agreed to accept the nomination if "it came to me unsought, unanimously, and without pledges to anybody about anything."Berg (2013), pp. 192–193

Works

''Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics.''

Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1885.

''The State: Elements of Historical and Practical Politics.''

Boston: D.C. Heath, 1889.

''Division and Reunion, 1829–1889.''

New York, London, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1893.

Old Master and Other Political Essays.''

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1893.

''Mere Literature and Other Essays.''

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1896.

''George Washington.''

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1897. * ''The History of the American People.'' In five volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1901–02.

Vol. 2

Vol. 3

Vol. 4

Vol. 5

/small>

''Constitutional Government in the United States.''

New York: Columbia University Press, 1908.

''The Free Life: A Baccalaureate Address.''

New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1908.

''The New Freedom: A Call for the Emancipation of the Energies of a Generous People.''

New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1913. —Speeches

''The Road Away from Revolution.''

Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1923. * ''The Public Papers of Woodrow Wilson.'' Ray Stannard Baker and William E. Dodd (eds.) In six volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1925–27. * ''Study of public administration'' (Washington:

Public Affairs Press

Public Affairs Press ( – mid-1980s) was a book publisher in Washington, D.C., owned and often edited by Morris Bartel Schnapper (1912–1999).

History

According to notional successor Peter Osnos of the 1997-founded PublicAffairs: For ...

, 1955)

* ''A Crossroads of Freedom: The 1912 Campaign Speeches of Woodrow Wilson.'' John Wells Davidson (ed.) New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1956.

* ''The Papers of Woodrow Wilson.'' Arthur S. Link (ed.) In 69 volumes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967–1994.

See also

*Presidency of Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson's tenure as the 28th president of the United States lasted from 4 March 1913 until 4 March 1921. He was largely incapacitated the last year and a half. He became president after winning the 1912 election. Wilson was a Democr ...

*Joseph Patrick Tumulty

Joseph Patrick Tumulty (pronounced TUM-ulty; May 5, 1879 – April 9, 1954) was an American attorney and politician from New Jersey. He was a leader of the Irish Catholic political community. He is best known for his service from 1911 until 1921 ...

* Woodrow Wilson and race

*Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

*William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

Notes

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** ** * * * * * * * * * * * {{cite book , last=Wilson, first=Woodrow, url= https://archive.org/stream/congressionalgov00wilsiala#page/n5/mode/2up , title= Congressional Government, A Study in American Politics , year= 1885 , publisher= Houghton, Mifflin and Company , via=Internet Archive, oclc=504641398 Woodrow Wilson Wilson, Woodrow Wilson, Woodrow