Early life of Joseph Stalin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The early life of Joseph Stalin covers the period from Stalin's birth, on 18 December 1878 (6 December according to the Old Style), until the

The early life of Joseph Stalin covers the period from Stalin's birth, on 18 December 1878 (6 December according to the Old Style), until the

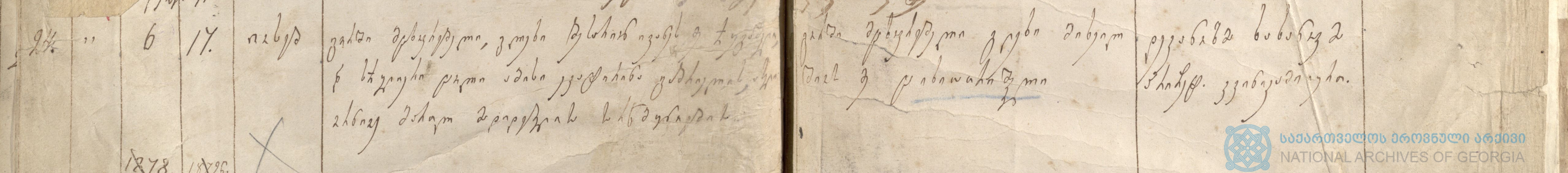

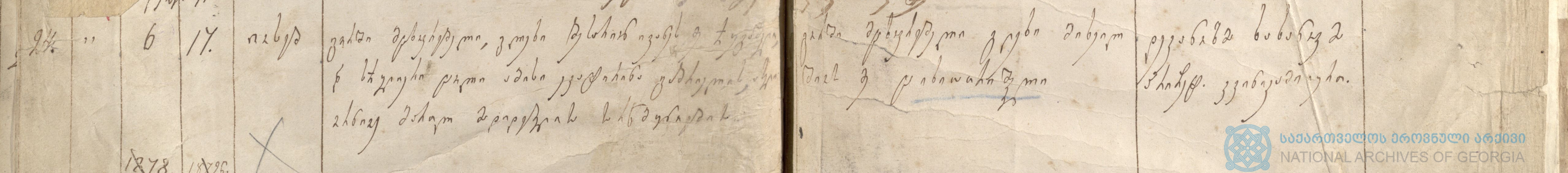

Stalin was born Ioseb Jughashvili on in the town of Gori, in what is today the country of Georgia. He was baptised on and christened Ioseb, and known by the

Stalin was born Ioseb Jughashvili on in the town of Gori, in what is today the country of Georgia. He was baptised on and christened Ioseb, and known by the  When Stalin was twelve, he was seriously injured after having been hit by a phaeton. He was hospitalised in Tiflis for several months, and sustained a lifelong disability to his left arm. His father subsequently kidnapped him and enrolled him as an apprentice cobbler in the factory; this would be Stalin's only experience as a worker. According to Stalin's biographer Robert Service, this was Stalin's "first experience with capitalism", and it was "raw, harsh and dispiriting". Several priests from Gori retrieved the boy, after which Beso cut all contact with his wife and son. In February 1892, Stalin's school teachers took him and the other pupils to witness the public

When Stalin was twelve, he was seriously injured after having been hit by a phaeton. He was hospitalised in Tiflis for several months, and sustained a lifelong disability to his left arm. His father subsequently kidnapped him and enrolled him as an apprentice cobbler in the factory; this would be Stalin's only experience as a worker. According to Stalin's biographer Robert Service, this was Stalin's "first experience with capitalism", and it was "raw, harsh and dispiriting". Several priests from Gori retrieved the boy, after which Beso cut all contact with his wife and son. In February 1892, Stalin's school teachers took him and the other pupils to witness the public

In July 1893, Stalin passed his exams and his teachers recommended him to the Tiflis Seminary. Keke took him to the city, where they rented a room. Stalin applied for a scholarship to enable him to attend the school; they accepted him as a half-boarder, meaning that he was required to pay a reduced fee of 40 roubles a year. This was still a substantial sum for his mother, and he was likely financially assisted once more by family friends. He officially enrolled at the school in August 1894. Here he joined 600 trainee priests, who boarded in dormitories containing between twenty and thirty beds. Stalin was set apart by being three years older than most of the other first year students, although a number of his fellow students had also attended the Gori Church School. At Tiflis, Stalin was again an academically successful pupil, gaining high grades in his subjects. Among the subjects taught at the seminary were Russian literature; secular history; mathematics; Latin; Greek; Church Slavonic singing; Georgian Imeretian singing; and Holy Scripture. As students progressed they were taught more concentrated theological subjects such as ecclesiastical history; liturgy; homiletics; comparative theology; moral theology; practical pastoral work; didactics; and church singing. To earn money, he sang in a choir, with his father sometimes asking him for his earnings. During the holidays he would return to Gori to spend time with his mother.

Tiflis was a multi-ethnic city in which Georgians were a minority. The Seminary was controlled by the

In July 1893, Stalin passed his exams and his teachers recommended him to the Tiflis Seminary. Keke took him to the city, where they rented a room. Stalin applied for a scholarship to enable him to attend the school; they accepted him as a half-boarder, meaning that he was required to pay a reduced fee of 40 roubles a year. This was still a substantial sum for his mother, and he was likely financially assisted once more by family friends. He officially enrolled at the school in August 1894. Here he joined 600 trainee priests, who boarded in dormitories containing between twenty and thirty beds. Stalin was set apart by being three years older than most of the other first year students, although a number of his fellow students had also attended the Gori Church School. At Tiflis, Stalin was again an academically successful pupil, gaining high grades in his subjects. Among the subjects taught at the seminary were Russian literature; secular history; mathematics; Latin; Greek; Church Slavonic singing; Georgian Imeretian singing; and Holy Scripture. As students progressed they were taught more concentrated theological subjects such as ecclesiastical history; liturgy; homiletics; comparative theology; moral theology; practical pastoral work; didactics; and church singing. To earn money, he sang in a choir, with his father sometimes asking him for his earnings. During the holidays he would return to Gori to spend time with his mother.

Tiflis was a multi-ethnic city in which Georgians were a minority. The Seminary was controlled by the  Over his years at the Seminary, Stalin lost interest in many of his studies and his grades began to drop. He grew his hair long in an act of rebellion against the school's rules. Seminary records contain complaints that he declared himself an atheist, chatted in class, was late for meals, and refused to doff his hat to monks. He was repeatedly confined to a cell for his rebellious behaviour. He had joined a forbidden book club, the Cheap Library, which was active at the school. Among the authors whom he read in this period were

Over his years at the Seminary, Stalin lost interest in many of his studies and his grades began to drop. He grew his hair long in an act of rebellion against the school's rules. Seminary records contain complaints that he declared himself an atheist, chatted in class, was late for meals, and refused to doff his hat to monks. He was repeatedly confined to a cell for his rebellious behaviour. He had joined a forbidden book club, the Cheap Library, which was active at the school. Among the authors whom he read in this period were

On 9 July 1903, the Justice Minister recommended that Stalin be sentenced to three years of exile in eastern Siberia. Stalin began his journey east in October, when he boarded a prison steamship at Batumi harbour and travelled via

On 9 July 1903, the Justice Minister recommended that Stalin be sentenced to three years of exile in eastern Siberia. Stalin began his journey east in October, when he boarded a prison steamship at Batumi harbour and travelled via

For some time, Stalin had been living in a central Tiflis apartment owned by the Alliluyev family. He and one of the members of this family,

For some time, Stalin had been living in a central Tiflis apartment owned by the Alliluyev family. He and one of the members of this family,

By July 1909, Stalin was back in Baku. There he began to express the need for the Bolsheviks to help boost their ailing fortunes by re-uniting with the Mensheviks. He was increasingly frustrated with Lenin's factionalist attitudes.

In October 1909, Stalin was arrested alongside several fellow Bolsheviks, but bribed the police officers into letting them escape. He was arrested again on 23 March 1910, this time with Petrovskaya. He was sentenced into internal exile and sent back to Solvychegodsk, being banned from returning to the southern Caucuses for five years. He had gained permission to marry Petrovskaya in the prison church, but he was deported on the same day—23 September 1910—that he received permission to do so. He would never see her again. In Solvychegodsk, he commenced a relationship with a teacher, Serafima Khoroshenina, and before February 1911 had registered as her cohabiting partner; she however was soon exiled to

By July 1909, Stalin was back in Baku. There he began to express the need for the Bolsheviks to help boost their ailing fortunes by re-uniting with the Mensheviks. He was increasingly frustrated with Lenin's factionalist attitudes.

In October 1909, Stalin was arrested alongside several fellow Bolsheviks, but bribed the police officers into letting them escape. He was arrested again on 23 March 1910, this time with Petrovskaya. He was sentenced into internal exile and sent back to Solvychegodsk, being banned from returning to the southern Caucuses for five years. He had gained permission to marry Petrovskaya in the prison church, but he was deported on the same day—23 September 1910—that he received permission to do so. He would never see her again. In Solvychegodsk, he commenced a relationship with a teacher, Serafima Khoroshenina, and before February 1911 had registered as her cohabiting partner; she however was soon exiled to

In February 1913, Stalin was back in St. Petersburg. At the time, the Okhrana were cracking down on the Bolsheviks by arresting leading members. Stalin himself was arrested at a masquerade ball held by the Bolsheviks as a fundraiser at the Kalashnikov Exchange.

Stalin was subsequently sentenced to four years exile in Turukhansk, a remote part of Siberia from which escape was particularly difficult. In August, he arrived in the village of Monastyrskoe, although after four weeks was relocated to the hamlet of Kostino. Stalin wrote letters to many people whom he knew, begging for them to send him money, in part to finance his escape attempt. The authorities were concerned about any escape attempt and thus moved Stalin, along with Sverdlov, to the hamlet of Kureika, on the edge of the

In February 1913, Stalin was back in St. Petersburg. At the time, the Okhrana were cracking down on the Bolsheviks by arresting leading members. Stalin himself was arrested at a masquerade ball held by the Bolsheviks as a fundraiser at the Kalashnikov Exchange.

Stalin was subsequently sentenced to four years exile in Turukhansk, a remote part of Siberia from which escape was particularly difficult. In August, he arrived in the village of Monastyrskoe, although after four weeks was relocated to the hamlet of Kostino. Stalin wrote letters to many people whom he knew, begging for them to send him money, in part to finance his escape attempt. The authorities were concerned about any escape attempt and thus moved Stalin, along with Sverdlov, to the hamlet of Kureika, on the edge of the

by Sergey Zemlyanoy Nezavisimaya Gazeta 3 July 2002 It also appears suspicious that Stalin played down the number of his escapes from prisons and exiles.Тайные грабежи Сталина крышевал Ленин

The early life of Joseph Stalin covers the period from Stalin's birth, on 18 December 1878 (6 December according to the Old Style), until the

The early life of Joseph Stalin covers the period from Stalin's birth, on 18 December 1878 (6 December according to the Old Style), until the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

on 7 November 1917 (25 October). Born Ioseb Jughashvili in Gori, Georgia

Gori ( ka, გორი ) is a city in eastern Georgia, which serves as the regional capital of Shida Kartli and is located at the confluence of two rivers, the Mtkvari and the Liakhvi. Gori is the fifth most populous city in Georgia. Its name ...

, to a cobbler and a house cleaner, he grew up in the city and attended school there before moving to Tiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million pe ...

(modern-day Tbilisi) to join the Tiflis Seminary. While a student at the seminary he embraced Marxism and became an avid follower of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

, and left the seminary to become a revolutionary. After being marked by Russian secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

for his activities, he became a full-time revolutionary and outlaw. He became one of the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

' chief operatives in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

, organizing paramilitaries

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

, spreading propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

, raising money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are as ...

through bank robberies, and kidnappings and extortion

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit through coercion. In most jurisdictions it is likely to constitute a criminal offence; the bulk of this article deals with such cases. Robbery is the simplest and most common form of extortion, ...

. Stalin was captured and exile

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

d to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

numerous times, but often escaped. He became one of Lenin's closest associates, which helped him rise to the heights of power after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

. In 1913 Stalin was exiled to Siberia for the final time, and remained in exile until the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

of 1917 led to the overthrow of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

.

Childhood and Early Career

Childhood: 1878–1893

Stalin was born Ioseb Jughashvili on in the town of Gori, in what is today the country of Georgia. He was baptised on and christened Ioseb, and known by the

Stalin was born Ioseb Jughashvili on in the town of Gori, in what is today the country of Georgia. He was baptised on and christened Ioseb, and known by the diminutive

A diminutive is a root word that has been modified to convey a slighter degree of its root meaning, either to convey the smallness of the object or quality named, or to convey a sense of intimacy or endearment. A (abbreviated ) is a word-formati ...

"Soso"

His parents were Ekaterine (Keke) and Besarion Jughashvili

Besarion Ivanes dze Jughashvili,. This is the name that appears in the birth register entry for his son, Ioseb. The Russian version of his name was Виссарион Иванович Джугашвили, ''Vissarion Ivanovich Dzhugashvili''. ...

(Beso). He was their third child; the first two, Mikheil and Giorgi, had died in infancy.

Stalin's father, Besarion, was a shoemaker and owned a workshop that at one point employed as many as ten people, but which slid into ruin as Stalin grew up. Beso had specialised in producing traditional Georgian footwear and did not produce the European-style shoes that were becoming increasingly fashionable. This, combined with the deaths of his previous two infant sons, precipitated his decline into alcoholism. The family found themselves living in poverty. The couple had to leave their home and moved into nine different rented rooms over ten years.

Besarion also became violent towards his family. To escape the abusive relationship

Relational aggression or alternative aggressionSimmons, Rachel (2002). ''Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls''. New York, New York: Mariner Books. pp. 8–9. . Retrieved 2016-11-02. is a type of aggression in which harm is cause ...

, Keke took Stalin and moved into the house of a family friend, Father Christopher Charkviani. She worked as a house cleaner and launderer for several local families who were sympathetic to her plight. Keke was a strict but affectionate mother to Stalin. She was a devout Christian, and both she and her son regularly attended church services. In 1884, Stalin contracted smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, which left him with facial pock marks for the rest of his life.

Charkviani's teenaged sons taught Stalin the Russian language. Keke was determined to send her son to school, something that none of the family had previously achieved. In late 1888, when Stalin was ten, he enrolled at the Gori Church School. This was normally reserved for the children of clergy, but Charkviani ensured that Stalin received a place by claiming that the boy was the son of a deacon. This may be the reason why—in 1934—Stalin claimed to have been the son of a priest. There were many local rumours that Beso was not Stalin's real father, which in later life Stalin himself encouraged. Stalin biographer Simon Sebag Montefiore nonetheless thought it likely that Beso was the father, in part due to the strong physical resemblance that they shared. Beso eventually attacked a policeman while drunk which resulted in the authorities ejecting him from Gori. He moved to Tiflis, where he worked at the Adelkhanov shoe factory.

Although Keke was poor, she ensured that her son was well dressed when he went to school, likely through the financial support of family friends. As a child, Stalin exhibited a number of idiosyncrasies; when happy, he would for instance jump around on one leg while clicking his fingers and yelling aloud.

He excelled academically, and also displayed talent in painting and drama classes. He began writing poetry, and was a fan of the work of Georgian nationalist writer Raphael Eristavi. He was also a choirboy, singing both in church and at local weddings.

A childhood friend of Stalin's later recalled that he "was the best but also the naughtiest pupil" in the class. He and his friends formed a gang, and often fought with other local children. He caused mischief; in one incident, he ignited explosive cartridges in a shop, and in another he tied a pan to the tail of a woman's pet cat.

When Stalin was twelve, he was seriously injured after having been hit by a phaeton. He was hospitalised in Tiflis for several months, and sustained a lifelong disability to his left arm. His father subsequently kidnapped him and enrolled him as an apprentice cobbler in the factory; this would be Stalin's only experience as a worker. According to Stalin's biographer Robert Service, this was Stalin's "first experience with capitalism", and it was "raw, harsh and dispiriting". Several priests from Gori retrieved the boy, after which Beso cut all contact with his wife and son. In February 1892, Stalin's school teachers took him and the other pupils to witness the public

When Stalin was twelve, he was seriously injured after having been hit by a phaeton. He was hospitalised in Tiflis for several months, and sustained a lifelong disability to his left arm. His father subsequently kidnapped him and enrolled him as an apprentice cobbler in the factory; this would be Stalin's only experience as a worker. According to Stalin's biographer Robert Service, this was Stalin's "first experience with capitalism", and it was "raw, harsh and dispiriting". Several priests from Gori retrieved the boy, after which Beso cut all contact with his wife and son. In February 1892, Stalin's school teachers took him and the other pupils to witness the public hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

of several peasant bandits; Stalin and his friends sympathised with the condemned. The event left a deep and lasting impression on him. Stalin had decided that he wanted to become a local administrator so that he could deal with the problems of poverty that affected the population around Gori. Despite his Christian upbringing, he had become an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

after contemplating the problem of evil

The problem of evil is the question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God.The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,The Problem of Evil, Michael TooleyThe Internet Encyclope ...

and learning about evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

through Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

''.

Tiflis Seminary: 1893–1899

In July 1893, Stalin passed his exams and his teachers recommended him to the Tiflis Seminary. Keke took him to the city, where they rented a room. Stalin applied for a scholarship to enable him to attend the school; they accepted him as a half-boarder, meaning that he was required to pay a reduced fee of 40 roubles a year. This was still a substantial sum for his mother, and he was likely financially assisted once more by family friends. He officially enrolled at the school in August 1894. Here he joined 600 trainee priests, who boarded in dormitories containing between twenty and thirty beds. Stalin was set apart by being three years older than most of the other first year students, although a number of his fellow students had also attended the Gori Church School. At Tiflis, Stalin was again an academically successful pupil, gaining high grades in his subjects. Among the subjects taught at the seminary were Russian literature; secular history; mathematics; Latin; Greek; Church Slavonic singing; Georgian Imeretian singing; and Holy Scripture. As students progressed they were taught more concentrated theological subjects such as ecclesiastical history; liturgy; homiletics; comparative theology; moral theology; practical pastoral work; didactics; and church singing. To earn money, he sang in a choir, with his father sometimes asking him for his earnings. During the holidays he would return to Gori to spend time with his mother.

Tiflis was a multi-ethnic city in which Georgians were a minority. The Seminary was controlled by the

In July 1893, Stalin passed his exams and his teachers recommended him to the Tiflis Seminary. Keke took him to the city, where they rented a room. Stalin applied for a scholarship to enable him to attend the school; they accepted him as a half-boarder, meaning that he was required to pay a reduced fee of 40 roubles a year. This was still a substantial sum for his mother, and he was likely financially assisted once more by family friends. He officially enrolled at the school in August 1894. Here he joined 600 trainee priests, who boarded in dormitories containing between twenty and thirty beds. Stalin was set apart by being three years older than most of the other first year students, although a number of his fellow students had also attended the Gori Church School. At Tiflis, Stalin was again an academically successful pupil, gaining high grades in his subjects. Among the subjects taught at the seminary were Russian literature; secular history; mathematics; Latin; Greek; Church Slavonic singing; Georgian Imeretian singing; and Holy Scripture. As students progressed they were taught more concentrated theological subjects such as ecclesiastical history; liturgy; homiletics; comparative theology; moral theology; practical pastoral work; didactics; and church singing. To earn money, he sang in a choir, with his father sometimes asking him for his earnings. During the holidays he would return to Gori to spend time with his mother.

Tiflis was a multi-ethnic city in which Georgians were a minority. The Seminary was controlled by the Georgian Orthodox Church

The Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia ( ka, საქართველოს სამოციქულო ავტოკეფალური მართლმადიდებელი ეკლესია, tr), commonly ...

, which was part of the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

and subordinate to the ecclesiastical authorities in St. Petersburg. The priests employed to work there were largely reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

, anti-semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, Russian nationalists. They banned the speaking of Georgian by pupils, insisting that Russian be used at all times. Stalin was however proud to be Georgian.

He continued writing poetry, and took several of his poems to the office of the newspaper ''Iveria'' ("Georgia"). There, they were read by Ilia Chavchavadze

Prince Ilia Chavchavadze ( ka, ილია ჭავჭავაძე; 8 November 1837 – 12 September 1907) was a Georgian public figure, journalist, publisher, writer and poet who spearheaded the revival of Georgian nationalism during the ...

, who liked them and ensured that five were published in the newspaper. Each was published under the pseudonym of "Soselo". Thematically, they dealt with topics like nature, land, and patriotism. According to Montefiore, they became "minor Georgian classics", and were included in various anthologies of Georgian poetry over the coming years. Montefiore was of the view that "their romantic imagery was derivative but their beauty lay in the delicacy and purity of rhythm and language". Similarly, Service felt that in the original Georgian language these poems had "a linguistic purity recognised by all".

Over his years at the Seminary, Stalin lost interest in many of his studies and his grades began to drop. He grew his hair long in an act of rebellion against the school's rules. Seminary records contain complaints that he declared himself an atheist, chatted in class, was late for meals, and refused to doff his hat to monks. He was repeatedly confined to a cell for his rebellious behaviour. He had joined a forbidden book club, the Cheap Library, which was active at the school. Among the authors whom he read in this period were

Over his years at the Seminary, Stalin lost interest in many of his studies and his grades began to drop. He grew his hair long in an act of rebellion against the school's rules. Seminary records contain complaints that he declared himself an atheist, chatted in class, was late for meals, and refused to doff his hat to monks. He was repeatedly confined to a cell for his rebellious behaviour. He had joined a forbidden book club, the Cheap Library, which was active at the school. Among the authors whom he read in this period were Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

, Nikolay Nekrasov

Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov ( rus, Никола́й Алексе́евич Некра́сов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɐlʲɪkˈsʲejɪvʲɪtɕ nʲɪˈkrasəf, a=Ru-Nikolay_Alexeyevich_Nekrasov.ogg, – ) was a Russian poet, writer, critic and publi ...

, Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; uk, link=no, Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, translit=Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; (russian: Яновский; uk, Яновський, translit=Yanovskyi) ( – ) was a Russian novelist, ...

, Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; 29 January 1860 Old Style date 17 January. – 15 July 1904 Old Style date 2 July.) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer who is considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career ...

, Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, and philosopher. During the last seventeen years of his life (1788–1805), Schiller developed a productive, if complicated, friends ...

, Guy de Maupassant

Henri René Albert Guy de Maupassant (, ; ; 5 August 1850 – 6 July 1893) was a 19th-century French author, remembered as a master of the short story form, as well as a representative of the Naturalist school, who depicted human lives, destin ...

, Honoré de Balzac, and William Makepeace Thackeray. Particularly influential was Nikolay Chernyshevsky's 1863 pro-revolutionary novel ''What Is To Be Done?

''What Is to Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement'' is a political pamphlet written by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin (credited as N. Lenin) in 1901 and published in 1902. Lenin said that the article represented "a skeleton plan t ...

''. Another influential text was Alexander Kazbegi

Alexander Kazbegi ( ka, ალექსანდრე ყაზბეგი, ) (1848–1893) was a Georgian writer, famous for his 1883 novel ''The Patricide''.

Early life

Kazbegi was born in Stepantsminda the great grandson of Kazibek Chop ...

's ''The Patricide

''The Patricide'' ( ka, მამის მკვლელი) is a novel by Alexander Kazbegi, first published in 1882. The novel is a love story, but it also addresses many socio-political issues of 19th century Georgia. The novel portrays criti ...

'', with Stalin adopting the nickname "Koba" from that of the book's bandit protagonist. These works of fiction were supplemented with the writings of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and books on Russian and French history.

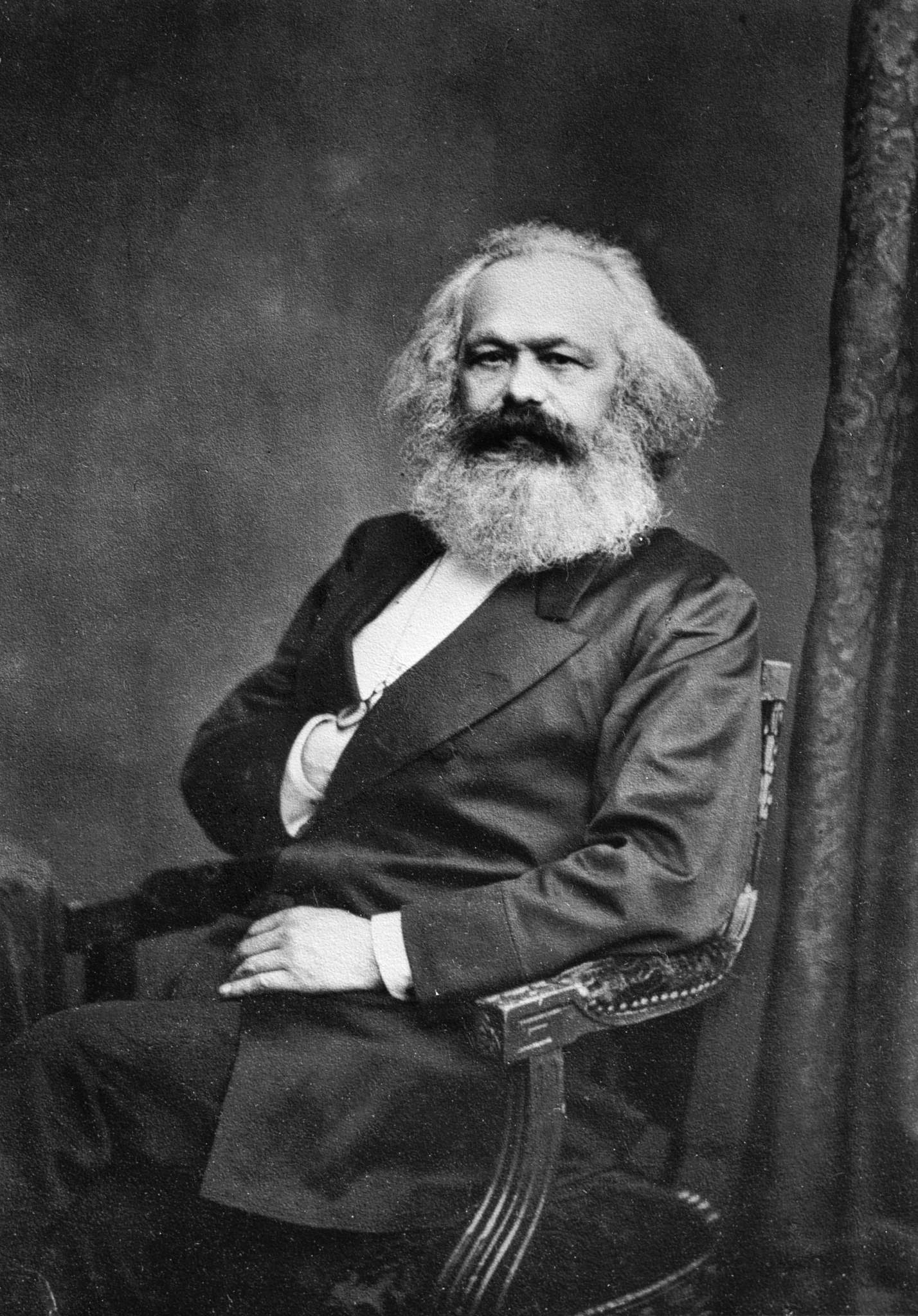

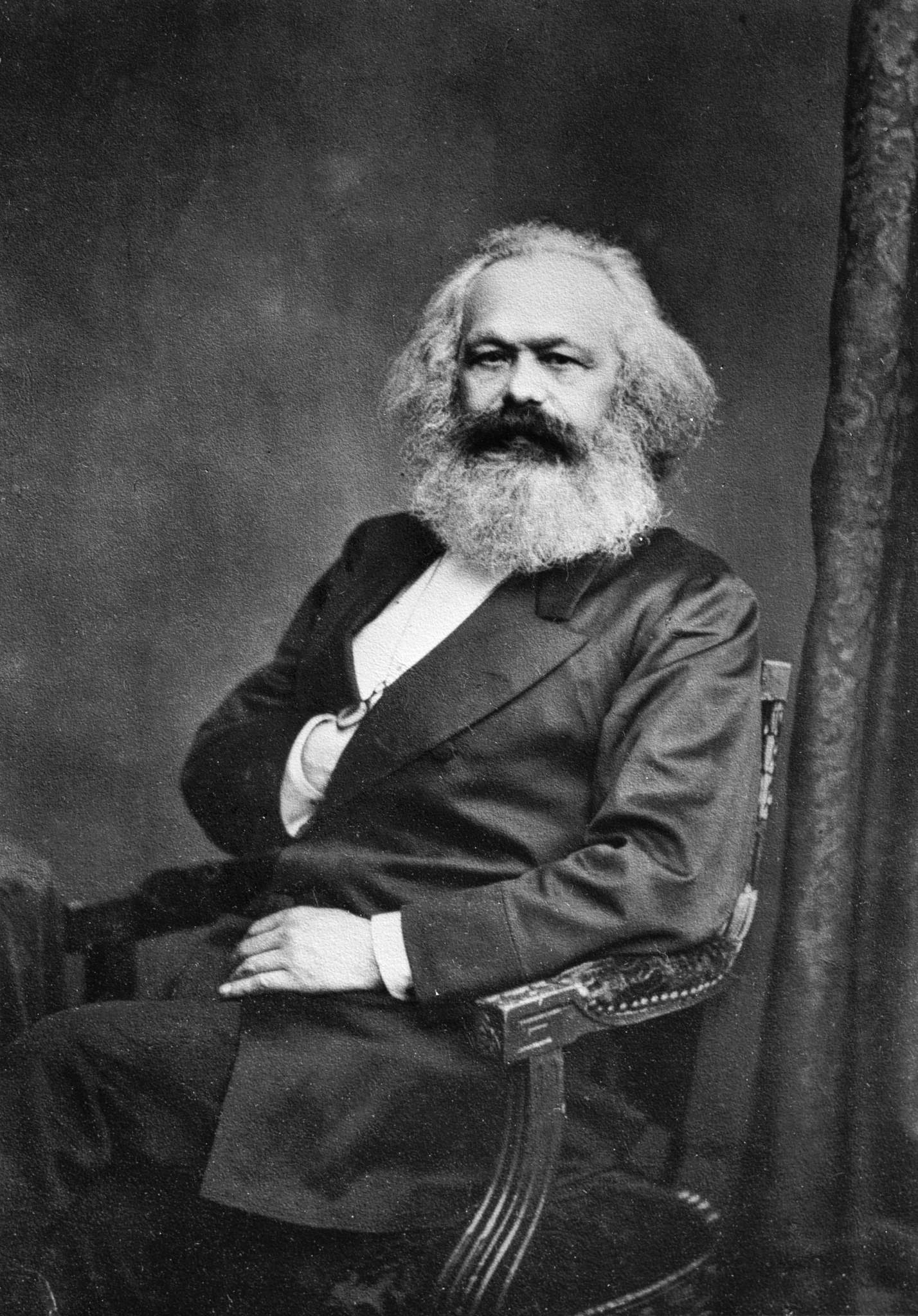

He also read ''Capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

'', the 1867 book by German sociological theorist Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, and tried learning German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

so that he could read the works of Marx and his collaborator Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Marxism Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, the socio-political theory that Marx and Engels had developed. Marxism provided him with a new way of interpreting the world. The ideology was on the rise in Georgia, one of various forms of '' Marxism Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

then developing in opposition to the governing Tsarist authorities. At night, he attended secret meetings of local workers, most of whom were Russian. He was introduced to Silibistro "Silva" Jibladze, the Marxist founder of Mesame Dasi ('Third Group'), a Georgian socialist group. One of his poems was published in the group's newspaper, ''Kvali''.

Stalin found many socialists active in the Russian Empire to be too moderate, but was attracted by the writings of a Marxist who used the pseudonym of "Tulin"; this was Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

. It is also possible that he had pursued romantic and sexual relationships with women in Tiflis. Years later, there was some suggestion that he might have fathered a girl named Praskovia "Pasha" Mikhailovskaya around this period.

In April 1899, Stalin left the seminary at the end of term and never returned, although the school encouraged him to come back. Through his years of attendance, he had received a classical education but had not qualified as a priest. In later years, he sought to glamourize his leaving, claiming that he had been expelled from the seminary for his revolutionary activities.

Early revolutionary activity: 1899–1902

Stalin next worked as a tutor for middle class children, but earned a meager living. In October 1899, Stalin began work as a meteorologist at the Tiflis Meteorological Observatory, where his school-friend Vano Ketskhoveli was already employed. In this position, he worked during the night for a wage of twenty roubles a month. The position entailed little work, and allowed him to read while on duty. According to Robert Service, this was Stalin's "only period of sustained employment until after the October Revolution". In the early weeks of 1900, Stalin was arrested and held in Metekhi Fortress. The official explanation given was that Beso had not paid his taxes and that Stalin was responsible for ensuring that they were paid, although it may be that this was a "cryptic warning" from the police, who were aware of Stalin's Marxist revolutionary activities. As soon as she learned of the arrest, Keke came to Tiflis, while some of Stalin's wealthier friends helped to pay the taxes and get him out of prison. Stalin had attracted a group of radical young men around him, giving classes in socialist theory in a flat on Sololaki Street. Stalin was involved in organising a secret nocturnal mass meeting for May Day 1900, in which around 500 workers met in the hills outside the city. There, Stalin gave his first major public speech, in which he called for strike action, something that the Mesame Dasi opposed. Following his prompting, the workers at the railway depos and Adelkhanov's show factory went on strike. By this point, the Tsarist secret police—theOkhrana

The Department for Protecting the Public Security and Order (russian: Отделение по охранению общественной безопасности и порядка), usually called Guard Department ( rus, Охранное отд ...

—were aware of Stalin's activities within Tiflis' revolutionary milieu. On the night of 21–22 March 1901, the Okhrana arrested a number of Marxist leaders in the city. Stalin himself escaped arrest; he was traveling toward the observatory aboard a tram when he recognised plain-clothes police around the building. He decided to remain on the tram and get off at a later stop. He did not return to the observatory, and henceforth lived off of donations given by political sympathisers and friends.

Stalin next helped plan a large May Day demonstration for 1901, in which 3000 workers and leftists marched from Soldiers Bazaar to Yerevan Square. Demonstrators clashed with Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

troops, resulting in 14 protesters being seriously wounded and 50 arrested. After this event, Stalin escaped several further attempts to arrest him. To evade detection, he slept in at least six different apartments and used the alias of "David". Soon after, one of Stalin's associates, Stepan Shaumian

Stepan Georgevich Shaumian (; , ''Step’an Ge'vorgi Shahumyan''; 1 October 1878 – 20 September 1918) was a Bolshevik revolutionary and politician active throughout the Caucasus. Arzumanyan, M. Շահումյան, Ստեփան Գևորգի. ...

, organised the assassination of the railway boss director who resisted the strikers.

In November 1901, Stalin attended a meeting of the Tiflis Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

, where he was elected one of the eight Committee members.

The Committee then sent Stalin to the port city of Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ) is the second largest city of Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast of the Black Sea in Georgia's southwest. It is situated in a subtropical zone at the foot of th ...

, where he arrived in November 1901.

He identified an Okhrana infiltrator who was trying to gain access to the Batumi Marxist circles, and they were subsequently killed. According to Montefiore, this was "probably talin'sfirst murder". In Batumi, Stalin moved around different flats, and it is likely that he had a relationship with Natasha Kirtava, whom he stayed with in Barskhana. Stalin's rhetoric proved divisive among the city's Marxists. His Batumi supporters became known as "Sosoists" while he was criticised by those regarded as "legals". Some of the "legals" suspected that Stalin might be an '' agent provocateur'' sent by the Tsarist authorities to infiltrate and discredit the movement.

In Batumi, Stalin gained employment at Rothschild

Rothschild () is a name derived from the German ''zum rothen Schild'' (with the old spelling "th"), meaning "with the red sign", in reference to the houses where these family members lived or had lived. At the time, houses were designated by signs ...

refinery storehouse. On 4 January 1902, the warehouse where he worked was set alight. The company's workers helped to put out the blaze, and insisted that they be paid a bonus for doing so. When the company refused, Stalin called a strike. He encouraged revolutionary fervour among workers through a number of leaflets that he had printed in both Georgian and Armenian. On 17 February, the Rothschild company agreed to the strikers' demands, which included a 30% pay rise. On 23 February, they then dismissed 389 workers whom they regarded as troublemakers. In response to this latter act, Stalin called for another strike.

Many of the strike leaders were arrested by police. Stalin helped to organise a public demonstration outside the prison which was joined by much of the town. The demonstrators stormed the prison in an attempt to free the imprisoned strike leaders, but were fired upon by Cossack troops. 13 protesters were killed and 54 wounded. Stalin escaped with a wounded man. This event, known as the Batumi Massacre, gained national attention. Stalin then helped to organise a further demonstration for 12 March, the day on which the dead were buried. Around 7000 people took part in the march, which was heavily policed. By this point, the Okhrana had become aware of Stalin's significant role in the demonstrations. On 5 April, they arrested him at the house of one of his fellow revolutionaries.

Imprisonment: 1902–1904

Stalin was initially interned in Batumi Prison. He soon established himself as a powerful and respected figure within the prison, and retained contacts with the outside world. On two occasions his mother visited him. The state prosecutor subsequently ruled that there was insufficient evidence for Stalin being behind the Batumi disturbances, but he was instead indicted for his involvement in revolutionary activities in Tiflis. In April 1903, Stalin led a prison protest against the visit of the Exarch of the Georgian Church. As punishment, he was restricted tosolitary confinement

Solitary confinement is a form of imprisonment in which the inmate lives in a single cell with little or no meaningful contact with other people. A prison may enforce stricter measures to control contraband on a solitary prisoner and use additi ...

before being moved to the stricter Kutaisi Prison. There, he gave lectures and encouraged inmates to read revolutionary literature. He organised a protest to ensure that many of those imprisoned for political activities were housed together.

Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk ( rus, Новоросси́йск, p=nəvərɐˈsʲijsk; ady, ЦIэмэз, translit=Chəməz, p=t͡sʼɜmɜz) is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is one of the largest ports on the Black Sea. It is one of the few cities hono ...

and Rostov to Irkutsk

Irkutsk ( ; rus, Иркутск, p=ɪrˈkutsk; Buryat language, Buryat and mn, Эрхүү, ''Erhüü'', ) is the largest city and administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. With a population of 617,473 as of the 2010 Census, Irkutsk is ...

. He then travelled, by foot and coach, to Novaya Uda, arriving at the small settlement on 26 November. In the town, Stalin lived in the two-room house of a local peasant, sleeping in the building's larder. There were many other exiled leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

intellectuals in the town but Stalin eschewed them and preferred drinking alcohol with the petty criminals that had been exiled there. While Stalin was in exile, a split had developed in the RSDLP, between the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

who backed Lenin and the Mensheviks who backed Julius Martov

Julius Martov or L. Martov (Ма́ртов; born Yuliy Osipovich Tsederbaum; 24 November 1873 – 4 April 1923) was a politician and revolutionary who became the leader of the Mensheviks in early 20th-century Russia. He was arguably the closes ...

.

Stalin had several attempts to escape Novaya Uda. On the first attempt he made it to Balagansk

Balagansk (russian: Балага́нск) is an urban locality (a work settlement) and the administrative center of Balagansky District, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia.Law #49-OZ It is located on the left bank of the Angara River, downstream from Svirsk ...

, but suffered from frostbite

Frostbite is a skin injury that occurs when exposed to extreme low temperatures, causing the freezing of the skin or other tissues, commonly affecting the fingers, toes, nose, ears, cheeks and chin areas. Most often, frostbite occurs in the han ...

to his face and was forced to return. On the second attempt, he escaped Siberia and returned to Tiflis. It was while he was in the city that the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

broke out. In Tiflis, Stalin again lived in the homes of various friends, and also attended a Marxist circle led by Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. (''né'' Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Bolshevik revolutionary and a prominent Soviet politician.

Born in Moscow to parents who were both involved in revolutionary politics, Kamenev attended Imperial Moscow Uni ...

. A number of local Marxists called for Stalin's expulsion from the RSDLP because of his calls for the establishment of a separate Georgian Marxist movement. They saw this as a betrayal of Marxist internationalism and compared it to the views of the Jewish Bundists. Some referred to him as the "Georgian Bundist". Stalin was defended by the first Georgian Marxist to officially declare himself a Bolshevik, Mikha Tskhakaya, although the latter made the young man publicly renounce his views. He aligned himself with the Bolsheviks, growing to detest many of the Georgian Mensheviks. Menshevism was however the dominant revolutionary force in the Southern Caucuses, leaving the Bolsheviks as a minority. Stalin was able to establish a local Bolshevik stronghold in the mining town of Chiatura.

At workers' meetings around Georgia, Stalin frequently debated against the Mensheviks. He called for an opposition to inter-ethnic violence, an alliance between the proletariat and peasantry, and—in contrast to the Mensheviks—insisted that there could be no compromise with the middle-classes in the struggle to overthrow the Tsar. With Philip Makharadze

Filipp Yeseyevich Makharadze ( ka, ფილიპე მახარაძე, russian: Филипп Махарадзе; 9 March 1868 – 10 December 1941) was a Georgian Bolshevik revolutionary and government official.

Life

Born in the villag ...

, Stalin began editing a Georgian Marxist newspaper, ''Proletariatis Brdzola'' ("Proletarian Struggle"). He spent time in Batumi and Gori, before Tskhakaya sent him to Kutaisi to establish a Committee for the province of Imeretia and Mingrelia in July. On New Year's Eve

In the Gregorian calendar, New Year's Eve, also known as Old Year's Day or Saint Sylvester's Day in many countries, is the evening or the entire day of the last day of the year, on 31 December. The last day of the year is commonly referred to ...

1904, Stalin led a gang of workers who disrupted a party being held by a bourgeois liberal group.

The Revolution of 1905: 1905–1907

In January 1905, a massacre of protesters took place in St Petersburg that came to be known asBloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence agai ...

. Unrest soon spread across the Russian Empire in what came to be known as the Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

. Along with Poland, Georgia was one of the regions particularly affected. In February, Stalin was in Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world a ...

when a spate of ethnic violence broke out between Armenians and Azeris; at least 2,000 were killed. Stalin formed a Bolshevik Battle Squad which he ordered to try and keep the warring ethnic factions apart, also using the unrest to steal printing equipment. He proceeded to Tiflis, where he organised a demonstration of ethnic reconciliation. Amid the growing violence, Stalin formed his own armed Red Battle Squads, with the Mensheviks doing the same. These armed revolutionary groups disarmed local police and troops, and gained further weaponry by raiding government arsenals. They raised funds through a protection racket on large local businesses and mines. Stalin's militia launched attacks on the government's Cossack troops and Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

. After Cossacks opened fire on a student meeting, killing sixty of those assembled, Stalin retaliated in September by launching nine simultaneous attacks on the Cossacks. In October, Stalin's militia agreed to co-operate many of its attacks with the local Menshevik militia.

On 26 November 1905, the Georgian Bolsheviks elected Stalin and two others as their delegates to a Bolshevik conference due to be held in St. Petersburg. Using the alias of "Ivanovitch", Stalin set off by train in early December, and on arrival met with Lenin's wife Nadezhda Krupskaya

Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya ( rus, links=no, Надежда Константиновна Крупская, p=nɐˈdʲeʐdə kənstɐnˈtʲinəvnə ˈkrupskəjə; 27 February 1939) was a Russian revolutionary and the wife of Vladimir Lenin ...

, who informed them that the venue had been moved to Tammerfors

Tampere ( , , ; sv, Tammerfors, ) is a city in the Pirkanmaa region, located in the western part of Finland. Tampere is the most populous inland city in the Nordic countries. It has a population of 244,029; the urban area has a population o ...

in the Grand Duchy of Finland.

It was at the conference that Stalin met Lenin for the first time.

Although Stalin held Lenin in deep respect, he was vocal in his disagreement with Lenin's view that the Bolsheviks should field candidates for the forthcoming election to the State Duma

The State Duma (russian: Госуда́рственная ду́ма, r=Gosudárstvennaja dúma), commonly abbreviated in Russian as Gosduma ( rus, Госду́ма), is the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia, while the upper house ...

.

In Stalin's absence, General Fyodor Griiazanov had crushed the Tiflis rebels. Stalin's Battle Squads had to go into hiding and operate from the underground. When Stalin returned to the city, he co-organised the assassination of Griiazanov with local Mensheviks. Stalin also established a small group which he called the Bolshevik Expropriators Club, although it would more widely be known as the Group or Outfit. Containing about ten members, three of whom were women, the group procured arms, facilitated prison escapes, raided banks, and executed traitors. They utilised protection rackets to further finance their activities. During 1906, they carried out a series of bank robberies and hold-ups of stage coaches transporting money. The money collected was then divided; much of it was sent to Lenin while the rest was used to finance ''Proletariatis Brdzola''. Stalin had continued to edit this newspaper, and also contributed articles to it using the pseudonyms "Koba" and "Besoshvili".

In early April 1906, Stalin left Georgia to attend the RSDLP Fourth Congress in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

. He travelled via St Petersburg and the Finnish port of Hangö. This would be the first time that he had left the Russian Empire. The ship on which Stalin travelled, the ''Oihonna'', was shipwrecked; Stalin and the other passengers had to wait to be rescued. At the Congress, Stalin was one of 16 Georgians, but he was the only one who was a Bolshevik. There, the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks disagreed over the so-called "agrarian question". Both agreed that the land should be expropriated from the gentry, but whereas Lenin believed that it should be nationalised under state ownership, the Mensheviks called for it to be municipalised under the ownership of local districts. Stalin disagreed with both, arguing that peasants should be allowed to take control of the land themselves; in his view, this would strengthen the alliance between the peasantry and the proletariat. At the conference, the RSDLP—then led by its Menshevik majority—agreed that it would not raise funds using armed robbery. Lenin and Stalin disagreed with this decision.

Stalin returned to Tiflis via Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, arriving home in June.

For some time, Stalin had been living in a central Tiflis apartment owned by the Alliluyev family. He and one of the members of this family,

For some time, Stalin had been living in a central Tiflis apartment owned by the Alliluyev family. He and one of the members of this family, Kato Svanidze

Ekaterine "Kato" Svanidze, '; russian: Екатерина Семёновна Сванидзе, ' (2 April 1885 – 22 November 1907) was the first wife of Joseph Stalin and the mother of his eldest son, Yakov Dzhugashvili.

Born in Racha, in we ...

, gradually developed a romantic connection. They married in July 1906; despite his atheism, he agreed to her wish for a church wedding. The ceremony took place in a church at Tskhakaya on the night of 15–16 July. In September, Stalin then attended an RSDLP conference in Tiflis; of the 42 delegates, only 6 were Bolshevik, with Stalin openly expressing his contempt of the Mensheviks. On 20 September, his gang boarded the ''Tsarevich Giorgi'' steamship as it passed Cape Kodori and stole the money aboard. Stalin was possibly among those who carried out this operation.

Svanidze was subsequently arrested for her revolutionary connections, and shortly after her release—on 18 March 1907—she gave birth to Stalin's son, Yakov Yakov (alternative spellings: Jakov or Iakov, cyrl, Яков) is a Russian or Hebrew variant of the given names Jacob and James. People also give the nickname Yasha ( cyrl, Яша) or Yashka ( cyrl, Яшка) used for Yakov.

Notable people

People ...

. Stalin nicknamed his new-born son "Patsana".

By 1907—according to Robert Service—Stalin had established himself as "Georgia's leading Bolshevik".

Stalin travelled to the Fifth RSDLP Congress, held in London in May–June 1907, via St Petersburg, Stockholm, and Copenhagen. While in Denmark, he made a detour to Berlin for a secret meeting with Lenin to discuss the robberies. Stalin arrived in England and Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-west and Clacton-on- ...

and took the train to London. There, he rented a room in Stepney, part of the city's East End

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have uni ...

that housed a substantial Jewish émigré community from the Russian Empire. The congress took place at a church in Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ar ...

. He remained in London for about three weeks, helping to nurse Tskhahaya after the latter fell ill. He returned to Tiflis via Paris.

Tiflis Robbery: 1907–09

After returning to Tiflis, Stalin organized the robbing of a large delivery of money to the Imperial Bank on 26 June 1907. His gang ambushed the armed convoy inYerevan Square

Freedom Square or Liberty Square is located in the center of Tbilisi, Georgia, at the eastern end of Rustaveli Avenue. (In Georgian, it is თავისუფლების მოედანი ''Tavisuplebis moedani'', pronounced ).

Under ...

with gunfire and homemade bombs. Around 40 people were killed, but all of Jughashvili's gang managed to escape alive.

It is possible that Stalin hired a number of Socialist Revolutionaries to help him in the heist. Around 250,000 roubles were stolen. Service described it as "their greatest coup".

After the heist, Stalin took his wife and son away from Tiflis, settling in Baku. There, Mensheviks confronted Stalin about the robbery but he denied any involvement. These Mensheviks then voted to expel him from the RSDLP, but Stalin took no notice of them.

In Baku, he moved his family into a seafront house just outside the city. There, he edited two Bolshevik newspapers, ''Bakinsky Proletary'' and ''Gudok'' ("Whistle"). In August 1907, he travelled to Germany to attend the Seventh Congress of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

, which took place in Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the ...

. He had returned to Baku in September, where the city was undergoing another spate of ethnic violence. In the city, he helped to secure Bolshevik domination of the local RSDLP branch. While devoting himself to revolutionary activity, Stalin had been neglecting his wife and child. Kato fell ill with typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

, and so he took her back to Tiflis to be with her family. There, she died in his arms on 22 November 1907. Fearing that he would commit suicide, Stalin's friends confiscated his revolver. The funeral took place on 25 November at Kulubanskaya Church before her body was buried at St Nina's Church in Kukia. During the funeral, Stalin threw himself onto the coffin in grief; he then had to escape the churchyard when he saw Okhrana members approaching. He then left his son with his late wife's family in Tiflis.

There, Stalin reassembled the Outfit and began publicly calling for more workers' strikes. The Outfit continued to attack Black Hundreds, and raised finances by running protection rackets, counterfeiting currency, and carrying out robberies. One of the robberies carried out in this period was of a ship, the ''Nicholas I'', as it docked in Baku harbour. Not long after, the Outfit carried out a raid on Baku's naval arsenal, during which several guards were killed. They also kidnapped the children of several wealthy figures in order to extract ransom money. He also co-operated with Hummat, the Muslim Bolshevik group, and was involved in assisting the arming of the Persian Revolution against Shah Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar

Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar ( fa, محمدعلی شاه قاجار; 21 June 1872 – 5 April 1925, San Remo, Italy), Shah of Iran from 8 January 1907 to 16 July 1909. He was the sixth shah of the Qajar dynasty.

Biography

Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar ...

. At some point in 1908 he travelled to the Swiss city of Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

to meet with Lenin; he also met the Russian Marxist Georgi Plekhanov

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov (; rus, Гео́ргий Валенти́нович Плеха́нов, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj vəlʲɪnˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ plʲɪˈxanəf, a=Ru-Georgi Plekhanov-JermyRei.ogg; – 30 May 1918) was a Russian revoluti ...

, who exasperated him.

On 25 March 1908, Stalin was arrested in a police raid and interned in Bailov Prison. In prison, he studied Esperanto

Esperanto ( or ) is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it was intended to be a universal second language for international communi ...

, then regarding it as the language of the future. Leading the Bolsheviks imprisoned there, he organised discussion groups and had those suspected of being police spies killed. He planned an escape attempt but it was later cancelled. He was eventually sentenced to two years exile in the village of Solvychegodsk

Solvychegodsk (russian: Сольвычего́дск, lit. "salt on the Vychegda River") is a town in Kotlassky District of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia, located on the right-hand bank of the Vychegda River northeast of Kotlas, the administra ...

, Vologda Province. The journey there took three months, over the course of which he contracted typhus, and spent time in both Moscow's Butyrki Prison

Butyrskaya prison ( rus, Бутырская тюрьма, r= Butýrskaya tyurmá), usually known simply as Butyrka ( rus, Бутырка, p=bʊˈtɨrkə), is a prison in the Tverskoy District of central Moscow, Russia. In Imperial Russia it ...

and Vologda Prison. He finally arrived at the village in February 1909. There he stayed in a communal house with nine fellow exiles but repeatedly got into trouble with the local police chief; the latter locked Stalin up for reading revolutionary literature aloud and fined him for attending the theatre. While in the village, Stalin had an affair with an Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

n noblewoman and teacher, Stefania Petrovskaya. In June Stalin escaped the village and made it to Kotlas

Kotlas (russian: Ко́тлас) is a town in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Northern Dvina and Vychegda Rivers. Population:

Kotlas is the third largest town of Arkhangelsk Oblast in terms of population (after Ar ...

disguised as a woman. From there, he made it to St Petersburg, where he was hidden by supporters.

Launching ''Pravda'': 1909–12

By July 1909, Stalin was back in Baku. There he began to express the need for the Bolsheviks to help boost their ailing fortunes by re-uniting with the Mensheviks. He was increasingly frustrated with Lenin's factionalist attitudes.

In October 1909, Stalin was arrested alongside several fellow Bolsheviks, but bribed the police officers into letting them escape. He was arrested again on 23 March 1910, this time with Petrovskaya. He was sentenced into internal exile and sent back to Solvychegodsk, being banned from returning to the southern Caucuses for five years. He had gained permission to marry Petrovskaya in the prison church, but he was deported on the same day—23 September 1910—that he received permission to do so. He would never see her again. In Solvychegodsk, he commenced a relationship with a teacher, Serafima Khoroshenina, and before February 1911 had registered as her cohabiting partner; she however was soon exiled to

By July 1909, Stalin was back in Baku. There he began to express the need for the Bolsheviks to help boost their ailing fortunes by re-uniting with the Mensheviks. He was increasingly frustrated with Lenin's factionalist attitudes.

In October 1909, Stalin was arrested alongside several fellow Bolsheviks, but bribed the police officers into letting them escape. He was arrested again on 23 March 1910, this time with Petrovskaya. He was sentenced into internal exile and sent back to Solvychegodsk, being banned from returning to the southern Caucuses for five years. He had gained permission to marry Petrovskaya in the prison church, but he was deported on the same day—23 September 1910—that he received permission to do so. He would never see her again. In Solvychegodsk, he commenced a relationship with a teacher, Serafima Khoroshenina, and before February 1911 had registered as her cohabiting partner; she however was soon exiled to Nikolsk

Nikolsk (russian: Нико́льск) is the name of several inhabited localities in Russia.

Modern localities Urban localities

*Nikolsk, Nikolsky District, Penza Oblast, a town in Nikolsky District of Penza Oblast

*Nikolsk, Vologda Oblast, a t ...

. He then entered into an affair with his landlady, Maria Kuzakova, with whom he fathered a son, Konstantin. He also spent time reading and planting pine trees.

Stalin was given permission to leave Solvychehodsk in June 1911. From there, he was required to stay in Vologda for two months, where he spent much of his time in the local library. There, he also had a relationship with the sixteen-year old Pelageya Onufrieva, who was already in an established relationship with the Bolshevik Peter Chizhikov. He then proceeded to St Petersburg, On 9 September 1911 he was again arrested, and held prisoner by the Okhrana for three weeks. He was then exiled to Vologda for three years. He was permitted to travel there on his own, but on the way hid from the authorities in St Petersburg for a while. He had hoped to attend a Prague Conference that Lenin was organising but did not have the funds. He then returned to Vologda, living in a house owned by a divorcee; it is likely that he had an affair with her.

At the Prague Conference, the first Bolshevik Central Committee was established; Lenin and Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, . Transliterated ''Grigorii Evseevich Zinov'ev'' according to the Library of Congress system. (born Hirsch Apfelbaum, – 25 August 1936), known also under the name Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky (russian: Ов ...

subsequently proposed co-opting the absent Stalin onto the group. Lenin believed that Stalin would be useful in helping to secure support for the Bolsheviks from the Empire's minority ethnicities.

According to Conquest, Lenin recognised Stalin as "a ruthless and dependable enforcer of the Bolsheviks' will".

Stalin was then appointed to the Central Committee, and would remain on it for the rest of his life. On 29 February, Stalin then took the train to St Petersburg via Moscow. There, his assigned task was to convert the Bolshevik weekly newspaper, ''Zvezda'' ("Star") into a daily, ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the co ...

'' ("Truth"). The new newspaper was launched in April 1912. Stalin served as its editor-in-chief, but did so secretly. He was assisted in the newspaper's production by Vyacheslav Scriabin. In the city, he stayed in the flat of Tatiana Slavatinskaya, with whom he had an affair.

The Outfit's last heist and the national question: 1912–13

By May 1912, he was back in Tiflis. He then returned to St Petersburg via Moscow, and stayed with N. G. Poletaev, the Bolsheviks' Duma deputy. During that same month Stalin was arrested again and imprisoned in the Shpalerhy Prison; in July he was sentenced to three years exile in Siberia. On 12 July, he arrived inTomsk

Tomsk ( rus, Томск, p=tomsk, sty, Түң-тора) is a city and the administrative center of Tomsk Oblast in Russia, located on the Tom River. Population:

Founded in 1604, Tomsk is one of the oldest cities in Siberia. The city is a not ...

, from which he took a steamship on the Ob River

}

The Ob ( rus, Обь, p=opʲ: Ob') is a major river in Russia. It is in western Siberia; and together with Irtysh forms the world's List of rivers by length, seventh-longest river system, at . It forms at the confluence of the Biya (river), Biya ...

to Kolpashevo, from which he travelled to Narym, where he was required to remain. There, he shared a room with the fellow Bolshevik Yakov Sverdlov. After only two months, Stalin escaped via canoe and made it to Tomsk by September. There he waited for Sverdlov to follow him, and the two proceeded to St Petersburg, where they were hidden by supporters.

Stalin returned to Tiflis, where the Outfit planned their last big action. They attempted to ambush a mail coach, but were unsuccessful; after fleeing, eighteen of their members were apprehended and arrested. Stalin returned to St Petersburg, where he continued editing and writing articles for ''Pravda'', moving from apartment to apartment. After the Duma elections of October 1912 resulted in six Bolsheviks and six Mensheviks being elected, Stalin began calling for reconciliation between the two Marxist factions in ''Pravda''. Lenin criticised him for this opinion, with Stalin declining to publish forty-seven of the articles which Lenin sent to him. With Valentina Lobova, he travelled to Krakow, a culturally Polish part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, to meet with Lenin. They continued to disagree on the issue of reunification with the Mensheviks. Stalin left and returned to St Petersburg but at Lenin's request he made a second trip to Krakow in December. Stalin and Lenin bonded on this latter visit, with the former eventually bowing to Lenin's views on reunification with the Mensheviks. On this trip, Stalin also made friends with Roman Malinovsky

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

, a Bolshevik who was secretly an informer for the Okhrana.

In January 1913, Stalin travelled to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, where he stayed with the wealthy Bolshevik sympathiser Alexander Troyanovsky. He was in the city at the same time as Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

, although he likely did not meet either of them at the time. There, he devoted himself to examining the 'national question' of how the Bolsheviks should deal with the various national and ethnic minorities living in the Russian Empire. Lenin had wanted to attract these minorities to the Bolshevik cause and to offer them the right of succession from the Russian state; at the same time, he hoped that they would not take up this offer and would want to remain part of a future Bolshevik-governed Russia. Stalin had not been able to read German, but had been assisted in studying German texts by writers like Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels in ...

and Otto Bauer by fellow Bolshevik Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

. He finished the article, which was titled '' Marxism and the National Question''. Lenin was very happy with it, and in a private letter to Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and social ...

he referred to Stalin as the "wonderful Georgian". According to Montefiore, this was "Stalin's most famous work".

The article was published in March 1913 under the pseudonym of "K. Stalin", a name he had been using since 1912. This name derived from the Russian language word for steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

(''stal''), and has been translated as "Man of Steel". It was—according to Service—an "unmistakably Russian name". Montefiore suggested that Stalin stuck with this name for the rest of his life because it had been used on the article which established his reputation within the Bolshevik movement.

Final exile: 1913–1917

In February 1913, Stalin was back in St. Petersburg. At the time, the Okhrana were cracking down on the Bolsheviks by arresting leading members. Stalin himself was arrested at a masquerade ball held by the Bolsheviks as a fundraiser at the Kalashnikov Exchange.

Stalin was subsequently sentenced to four years exile in Turukhansk, a remote part of Siberia from which escape was particularly difficult. In August, he arrived in the village of Monastyrskoe, although after four weeks was relocated to the hamlet of Kostino. Stalin wrote letters to many people whom he knew, begging for them to send him money, in part to finance his escape attempt. The authorities were concerned about any escape attempt and thus moved Stalin, along with Sverdlov, to the hamlet of Kureika, on the edge of the

In February 1913, Stalin was back in St. Petersburg. At the time, the Okhrana were cracking down on the Bolsheviks by arresting leading members. Stalin himself was arrested at a masquerade ball held by the Bolsheviks as a fundraiser at the Kalashnikov Exchange.

Stalin was subsequently sentenced to four years exile in Turukhansk, a remote part of Siberia from which escape was particularly difficult. In August, he arrived in the village of Monastyrskoe, although after four weeks was relocated to the hamlet of Kostino. Stalin wrote letters to many people whom he knew, begging for them to send him money, in part to finance his escape attempt. The authorities were concerned about any escape attempt and thus moved Stalin, along with Sverdlov, to the hamlet of Kureika, on the edge of the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at w ...