E.E. Cummings on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

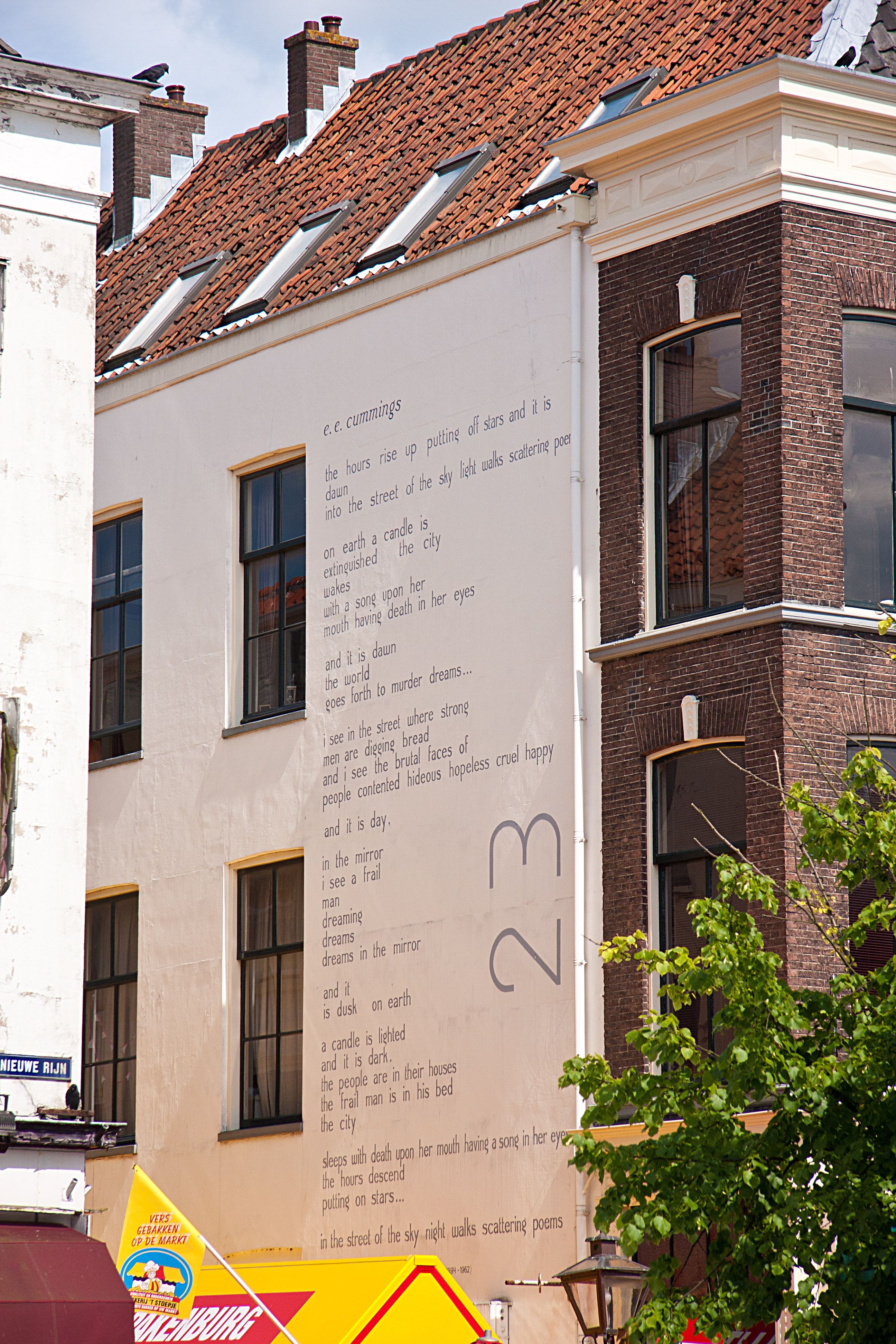

Edward Estlin Cummings, who was also known as E. E. Cummings, e. e. cummings and e e cummings (October 14, 1894 - September 3, 1962), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author and playwright. He wrote approximately 2,900 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays, and several essays. He is often regarded as one of the most important American poets of the 20th century. Cummings is associated with modernist free-form poetry. Much of his work has idiosyncratic syntax and uses lower-case spellings for poetic expression.

In 1952, his alma mater,

In 1952, his alma mater,

Cummings was married briefly twice, first to Elaine Thayer, then to Anne Minnerly Barton. His longest relationship lasted more than three decades with Marion Morehouse.

In 2020, it was revealed that in 1917, before his first marriage, Cummings had shared several passionate love letters with a Parisian prostitute, Marie Louise Lallemand. Despite Cummings' efforts, he was unable to find Lallemand upon his return to Paris after the front.

Cummings' first marriage, to Elaine Orr, his cousin, began as a love affair in 1918 while she was still married to Scofield Thayer, one of Cummings' friends from Harvard. During this time he wrote a good deal of his erotic poetry.''Selected Poems'', Ed. Richard S. Kennedy, Liveright, 1994. After divorcing Thayer, Orr married Cummings on March 19, 1924. The couple had a daughter together out of wedlock. However, the couple separated after two months of marriage and divorced less than nine months later.

Cummings married his second wife Anne Minnerly Barton on May 1, 1929. They separated three years later in 1932. That same year, Minnerly obtained a

Cummings was married briefly twice, first to Elaine Thayer, then to Anne Minnerly Barton. His longest relationship lasted more than three decades with Marion Morehouse.

In 2020, it was revealed that in 1917, before his first marriage, Cummings had shared several passionate love letters with a Parisian prostitute, Marie Louise Lallemand. Despite Cummings' efforts, he was unable to find Lallemand upon his return to Paris after the front.

Cummings' first marriage, to Elaine Orr, his cousin, began as a love affair in 1918 while she was still married to Scofield Thayer, one of Cummings' friends from Harvard. During this time he wrote a good deal of his erotic poetry.''Selected Poems'', Ed. Richard S. Kennedy, Liveright, 1994. After divorcing Thayer, Orr married Cummings on March 19, 1924. The couple had a daughter together out of wedlock. However, the couple separated after two months of marriage and divorced less than nine months later.

Cummings married his second wife Anne Minnerly Barton on May 1, 1929. They separated three years later in 1932. That same year, Minnerly obtained a

Life

Early years

Edward Estlin Cummings was born on October 14, 1894, inCambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, to Edward Cummings and the former Rebecca Haswell Clarke, a well-known Unitarian couple in the city. His father was a professor at Harvard University who later became nationally known as the minister of South Congregational Church (Unitarian) in Boston, Massachusetts. His mother, who loved to spend time with her children, played games with Cummings and his sister, Elizabeth. From an early age, Cummings' parents supported his creative gifts. Cummings wrote poems and drew as a child, and he often played outdoors with the many other children who lived in his neighborhood. He grew up in the company of such family friends as the philosophers William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

and Josiah Royce. Many of Cummings' summers were spent on Silver Lake

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

in Madison, New Hampshire, where his father had built two houses along the eastern shore. The family ultimately purchased the nearby Joy Farm

Joy Farm, also known as the E. E. Cummings House, is a historic farmstead on Joy Farm Road in the Silver Lake part of Madison, New Hampshire. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1971 in recognition for its place as the longtime summ ...

where Cummings had his primary summer residence.

He expressed transcendental

Transcendence, transcendent, or transcendental may refer to:

Mathematics

* Transcendental number, a number that is not the root of any polynomial with rational coefficients

* Algebraic element or transcendental element, an element of a field exten ...

leanings his entire life. As he matured, Cummings moved to an "I, Thou" relationship with God. His journals are replete with references to ''"le bon Dieu"'', as well as prayers for inspiration in his poetry and artwork (such as "Bon Dieu! may i some day do something truly great. amen."). Cummings "also prayed for strength to be his essential self ('may I be I is the only prayer—not may I be great or good or beautiful or wise or strong'), and for relief of spirit in times of depression ('almighty God! I thank thee for my soul; & may I never die spiritually into a mere mind through disease of loneliness')".

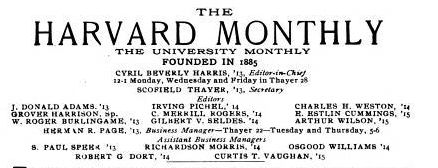

Cummings wanted to be a poet from childhood and wrote poetry daily from age 8 to 22, exploring assorted forms. He graduated from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

degree ''magna cum laude

Latin honors are a system of Latin phrases used in some colleges and universities to indicate the level of distinction with which an academic degree has been earned. The system is primarily used in the United States. It is also used in some So ...

'' and Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal a ...

in 1915 and received a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree from the university in 1916. In his studies at Harvard, he developed an interest in modern poetry, which ignored conventional grammar and syntax, while aiming for a dynamic use of language. Upon graduating, he worked for a book dealer.

War years

In 1917, with the First World War ongoing in Europe, Cummings enlisted in the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Corps. On the boat to France, he metWilliam Slater Brown

William Slater Brown (November 13, 1896 – June 22, 1997) was an American novelist, biographer, and translator of French literature. Most notably, he was a friend of the poet E. E. Cummings and is best known as the character "B." in Cumming ...

and they would become friends. Due to an administrative error, Cummings and Brown did not receive an assignment for five weeks, a period they spent exploring Paris. Cummings fell in love with the city, to which he would return throughout his life.

During their service in the ambulance corps, the two young writers sent letters home that drew the attention of the military censors. They were known to prefer the company of French soldiers over fellow ambulance drivers. The two openly expressed anti-war views; Cummings spoke of his lack of hatred for the Germans. On September 21, 1917, five months after starting his belated assignment, Cummings and William Slater Brown were arrested by the French military on suspicion of espionage and undesirable activities. They were held for three and a half months in a military detention camp at the '' Dépôt de Triage'', in La Ferté-Macé

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figur ...

, Orne, Normandy.

They were imprisoned with other detainees in a large room. Cummings' father failed to obtain his son's release through diplomatic channels, and in December 1917 he wrote a letter to President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

. Cummings was released on December 19, 1917, and Brown was released two months later. Cummings used his prison experience as the basis for his novel, ''The Enormous Room

''The Enormous Room (The Green-Eyed Stores)'' is a 1922 autobiographical novel by the poet and novelist E. E. Cummings about his temporary imprisonment in France during World War I.

Background

Cummings served as an ambulance driver during the wa ...

'' (1922), about which F. Scott Fitzgerald said, "Of all the work by young men who have sprung up since 1920 one book survives—''The Enormous Room'' by e.e. cummings ... Those few who cause books to live have not been able to endure the thought of its mortality."

Cummings returned to the United States on New Year's Day 1918. Later in 1918 he was drafted into the army. He served a training deployment in the 12th Division at Camp Devens, Massachusetts, until November 1918.

Post-war years

Cummings returned to Paris in 1921 and lived there for two years before returning to New York. His collection ''Tulips and Chimneys'' was published in 1923 and his inventive use of grammar and syntax is evident. The book was heavily cut by his editor. ''XLI Poems'' was published in 1925. With these collections, Cummings made his reputation as an avant garde poet. During the rest of the 1920s and 1930s, Cummings returned to Paris a number of times, and traveled throughout Europe, meeting, among others, artistPablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

. In 1931 Cummings traveled to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, recounting his experiences in ''Eimi Eimi may refer to:

* EIMI, a 1933 book by E. E. Cummings about a 1931 trip to the Soviet Union

* ''eimì'', an Ancient Greek verbs meaning "to be"

* Kuwaiti Persian

Kuwaiti Persian, known in Kuwait as ʿīmi (sometimes spelled Eimi)Written in A ...

'', published two years later. During these years Cummings also traveled to Northern Africa and Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

. He worked as an essayist and portrait artist for '' Vanity Fair'' magazine (1924–1927).

In 1926, Cummings' parents were in a car crash; only his mother survived, although she was severely injured. Cummings later described the crash in the following passage from his ''i: six nonlectures'' series given at Harvard (as part of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures) in 1952 and 1953:

His father's death had a profound effect on Cummings, who entered a new period in his artistic life. He began to focus on more important aspects of life in his poetry. He started this new period by paying homage to his father in the poem "my father moved through dooms of love".

In the 1930s Samuel Aiwaz Jacobs was Cummings' publisher; he had started the Golden Eagle Press after working as a typographer and publisher.

Final years

In 1952, his alma mater,

In 1952, his alma mater, Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, awarded Cummings an honorary seat as a guest professor. The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures he gave in 1952 and 1955 were later collected as ''i: six nonlectures''.

Cummings spent the last decade of his life traveling, fulfilling speaking engagements, and spending time at his summer home, Joy Farm

Joy Farm, also known as the E. E. Cummings House, is a historic farmstead on Joy Farm Road in the Silver Lake part of Madison, New Hampshire. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1971 in recognition for its place as the longtime summ ...

, in Silver Lake, New Hampshire

Silver Lake is an Unincorporated area, unincorporated community located at the north end of Silver Lake (Madison, New Hampshire), Silver Lake in the New England town, town of Madison, New Hampshire, in Carroll County, New Hampshire, Carroll County ...

. He died of a stroke on September 3, 1962, at the age of 67 at Memorial Hospital in North Conway, New Hampshire. Cummings was buried at Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston, Massachusetts. At the time of his death, Cummings was recognized as the "second most widely read poet in the United States, after Robert Frost

Robert Lee Frost (March26, 1874January29, 1963) was an American poet. His work was initially published in England before it was published in the United States. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloq ...

".

Cummings' papers are held at the Houghton Library at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

.

Personal life

Marriages

Cummings was married briefly twice, first to Elaine Thayer, then to Anne Minnerly Barton. His longest relationship lasted more than three decades with Marion Morehouse.

In 2020, it was revealed that in 1917, before his first marriage, Cummings had shared several passionate love letters with a Parisian prostitute, Marie Louise Lallemand. Despite Cummings' efforts, he was unable to find Lallemand upon his return to Paris after the front.

Cummings' first marriage, to Elaine Orr, his cousin, began as a love affair in 1918 while she was still married to Scofield Thayer, one of Cummings' friends from Harvard. During this time he wrote a good deal of his erotic poetry.''Selected Poems'', Ed. Richard S. Kennedy, Liveright, 1994. After divorcing Thayer, Orr married Cummings on March 19, 1924. The couple had a daughter together out of wedlock. However, the couple separated after two months of marriage and divorced less than nine months later.

Cummings married his second wife Anne Minnerly Barton on May 1, 1929. They separated three years later in 1932. That same year, Minnerly obtained a

Cummings was married briefly twice, first to Elaine Thayer, then to Anne Minnerly Barton. His longest relationship lasted more than three decades with Marion Morehouse.

In 2020, it was revealed that in 1917, before his first marriage, Cummings had shared several passionate love letters with a Parisian prostitute, Marie Louise Lallemand. Despite Cummings' efforts, he was unable to find Lallemand upon his return to Paris after the front.

Cummings' first marriage, to Elaine Orr, his cousin, began as a love affair in 1918 while she was still married to Scofield Thayer, one of Cummings' friends from Harvard. During this time he wrote a good deal of his erotic poetry.''Selected Poems'', Ed. Richard S. Kennedy, Liveright, 1994. After divorcing Thayer, Orr married Cummings on March 19, 1924. The couple had a daughter together out of wedlock. However, the couple separated after two months of marriage and divorced less than nine months later.

Cummings married his second wife Anne Minnerly Barton on May 1, 1929. They separated three years later in 1932. That same year, Minnerly obtained a Mexican divorce In the mid-20th century, some Americans traveled to Mexico to obtain a "Mexican divorce". A divorce in Mexico was easier, quicker, and less expensive than a divorce in most U.S. states, which then only allowed at-fault divorces requiring extensive ...

; it was not officially recognized in the United States until August 1934. Anne died in 1970 aged 72.

In 1934, after his separation from his second wife, Cummings met Marion Morehouse, a fashion model and photographer. Although it is not clear whether the two were ever formally married, Morehouse lived with Cummings until his death in 1962. She died on May 18, 1969, while living at 4 Patchin Place

Patchin Place is a gated cul-de-sac located off of 10th Street between Greenwich Avenue and the Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue) in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. Its ten 3-storyNew York City Landmarks Pr ...

, Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

, New York City, where Cummings had resided since September 1924.

Political views

According to his testimony in ''EIMI Eimi may refer to:

* EIMI, a 1933 book by E. E. Cummings about a 1931 trip to the Soviet Union

* ''eimì'', an Ancient Greek verbs meaning "to be"

* Kuwaiti Persian

Kuwaiti Persian, known in Kuwait as ʿīmi (sometimes spelled Eimi)Written in A ...

'', Cummings had little interest in politics until his trip to the Soviet Union in 1931. He subsequently shifted rightward on many political and social issues. Despite his radical and bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

public image, he was a Republican and later an ardent supporter of Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

.

Work

Poetry

Despite Cummings' familiarity withavant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

styles (likely affected by the ''Calligrammes

''Calligrammes: Poems of Peace and War 1913-1916'', is a collection of poems by Guillaume Apollinaire which was first published in 1918 (see 1918 in poetry). ''Calligrammes'' is noted for how the typeface and spatial arrangement of the words o ...

'' of French poet Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire) of the Wąż coat of arms. (; 26 August 1880 – 9 November 1918) was a French poet, playwright, short story writer, novelist, and art critic of Polish descent.

Apollinaire is considered one of the foremost poets of the ...

, according to a contemporary observation), much of his work is quite traditional. Many of his poems are sonnet

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's invention, ...

s, albeit often with a modern twist. He occasionally used the blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

form and acrostics

An acrostic is a poetry, poem or other word composition in which the ''first'' letter (or syllable, or word) of each new line (or paragraph, or other recurring feature in the text) spells out a word, message or the alphabet. The term comes from ...

. Cummings' poetry often deals with themes of love and nature, as well as the relationship of the individual to the masses and to the world. His poems are also often rife with satire.

While his poetic forms and themes share an affinity with the Romantic tradition, Cummings' work universally shows a particular idiosyncrasy of syntax

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure ( constituency) ...

, or way of arranging individual words into larger phrases and sentences. Many of his most striking poems do not involve any typographical or punctuation innovations at all, but purely syntactic ones.

As well as being influenced by notable modernists

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

, including Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

, Cummings in his early work drew upon the imagist

Imagism was a movement in early-20th-century Anglo-American poetry that favored precision of imagery and clear, sharp language. It is considered to be the first organized literary modernism, modernist literary movement in the English language. ...

experiments of Amy Lowell

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school, which promoted a return to classical values. She posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926.

Life

Amy Lowell was born on Febru ...

. Later, his visits to Paris exposed him to Dada and Surrealism

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to l ...

, which he reflected in his work. He began to rely on symbolism and allegory, where he once had used simile and metaphor. In his later work, he rarely used comparisons that required objects that were not previously mentioned in the poem, choosing to use a symbol instead. Due to this, his later poetry is "frequently more lucid, more moving, and more profound than his earlier". Cummings also liked to incorporate imagery of nature and death into much of his poetry.

While some of his poetry is free verse (with no concern for rhyme

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds (usually, the exact same phonemes) in the final stressed syllables and any following syllables of two or more words. Most often, this kind of perfect rhyming is consciously used for a musical or aesthetic ...

or meter), many have a recognizable sonnet structure of 14 lines, with an intricate rhyme scheme. A number of his poems feature a typographically exuberant style, with words, parts of words, or punctuation symbols scattered across the page, often making little sense until read aloud, at which point the meaning and emotion become clear. Cummings, who was also a painter, understood the importance of presentation, and used typography to "paint a picture" with some of his poems.

The seeds of Cummings' unconventional style appear well established even in his earliest work. At age six, he wrote to his father:

Following his autobiographical novel, ''The Enormous Room

''The Enormous Room (The Green-Eyed Stores)'' is a 1922 autobiographical novel by the poet and novelist E. E. Cummings about his temporary imprisonment in France during World War I.

Background

Cummings served as an ambulance driver during the wa ...

'', Cummings' first published work was a collection of poems titled ''Tulips and Chimneys

''Tulips and Chimneys'' is the first collection of poetry by E. E. Cummings, published in 1923.

Description

This collection is the first dedicated exclusively to Cummings's poetry;Pan, the mythical creature that is half-goat and half-man. Literary critic R.P. Blackmur has commented that this use of language is "frequently unintelligible because ummingsdisregards the historical accumulation of meaning in words in favour of merely private and personal associations".

Fellow poet

* '' CIOPW'' (1931), art works

*''i—six nonlectures'' (1953),

* '' CIOPW'' (1931), art works

*''i—six nonlectures'' (1953),

The Cummings Line on Race"

''Spring: The Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society'', vol. 4, pp. 71–75, Fall 1995. * Norman, Charles, ''E. E. Cummings: The Magic-Maker'', Boston, Little Brown, 1972. *

E. E. Cummings, Lifelong Unitarian

Biography of Cummings and his relationship with Unitarianism

E.E. Cummings Personal Library

at

Papers of E. E. Cummings

at the Houghton Library at

E. E. Cummings Collection

at the Harry Ransom Center at the

Poems by E. E. Cummings at PoetryFoundation.org

* ttp://faculty.gvsu.edu/websterm/cummings/ ''SPRING'':The Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society

Modern American Poetry

E. E. Cummings

at

Biography and poems of E. E. Cummings at Poets.org

Finding aid to Edward Estlin Cummings correspondence at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cummings, E. E. 1894 births 1962 deaths 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American poets American Field Service personnel of World War I American male poets American modernist poets American Unitarians Analysands of Fritz Wittels Bollingen Prize recipients Burials at Forest Hills Cemetery (Boston) Formalist poets Harvard Advocate alumni Lost Generation writers Massachusetts Republicans Military personnel from Massachusetts Modernist writers Old Right (United States) People from Carroll County, New Hampshire People from Greenwich Village Poets from Massachusetts Sonneteers Writers from Cambridge, Massachusetts Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American lyrical poet and playwright. Millay was a renowned social figure and noted feminist in New York City during the Roaring Twenties and beyond. She wrote much of he ...

, in her equivocal letter recommending Cummings for the Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the ar ...

he was awarded in 1934, expressed her frustration at his opaque symbolism. " he prints and offers for sale poetry which he is quite content should be, after hours of sweating concentration, inexplicable from any point of view to a person as intelligent as myself, then he does so with a motive which is frivolous from the point of view of art, and should not be helped or encouraged by any serious person or group of persons... there is fine writing and powerful writing (as well as some of the most pompous nonsense I ever let slip to the floor with a wide yawn)... What I propose, then, is this: that you give Mr. Cummings enough rope. He may hang himself; or he may lasso a unicorn."

Many of Cummings' poems are satirical and address social issues but have an equal or even stronger bias toward romanticism: time and again his poems celebrate love, sex, and the season of rebirth.

Cummings also wrote children's books and novels. A notable example of his versatility is an introduction he wrote for a collection of the comic strip ''Krazy Kat

''Krazy Kat'' (also known as ''Krazy & Ignatz'' in some reprints and compilations) is an US, American newspaper comic strip, by cartoonist George Herriman, which ran from 1913 to 1944. It first appeared in the ''New York Journal-American, New Yor ...

''.

Controversy

Cummings is known for controversial subject matter, as he wrote numerous erotic poems. He also sometimes included ethnic slurs in his writing. For instance, in his 1950 collection ''Xaipe: Seventy-One Poems'', Cummings published two poems containing words that caused outrage in some quarters.andone day a nigger caught in his hand a little star no bigger than not to understand i'll never let you go until you've made me white" so she did and now stars shine at night. Cummings, ''Xaipe, Seventy-one Poems''. New York: Oxford UP, 1950.

Cummings biographer Catherine Reef notes of the controversy: William Carlos Williams spoke out in his defense.''E. E. Cummings'' (2006) by Catherine Reef, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. 115a kike is the most dangerous machine as yet invented by even yankee ingenu ity(out of a jew a few dead dollars and some twisted laws) it comes both prigged and canted

Plays

During his lifetime, Cummings published four plays. '' HIM'', a three-act play, was first produced in 1928 by the Provincetown Players in New York City. The production was directed by James Light. The play's main characters are "Him", a playwright, portrayed by William Johnstone, and "Me", his girlfriend, portrayed by Erin O'Brien-Moore. Cummings said of the unorthodox play: ''Anthropos, or the Future of Art'' is a short, one-act play that Cummings contributed to the anthology ''Whither, Whither or After Sex, What? A Symposium to End Symposium''. The play consists of dialogue between Man, the main character, and three "infrahumans", or inferior beings. The word ''anthropos

Anthropos (ἄνθρωπος) is Greek for human.

Anthropos may also refer to:

* Anthropos, in Gnosticism, the first human being, also referred to as ''Adamas'' (from Hebrew meaning ''earth'') or ''Geradamas''

* ′Anthropos′ as a part of an ...

'' is the Greek word for "man", in the sense of "mankind".

''Tom, A Ballet'' is a ballet based on '' Uncle Tom's Cabin''. The ballet is detailed in a "synopsis" as well as descriptions of four "episodes", which were published by Cummings in 1935. It has never been performed.

'' Santa Claus: A Morality'' was probably Cummings' most successful play. It is an allegorical Christmas fantasy presented in one act of five scenes. The play was inspired by his daughter Nancy, with whom he was reunited in 1946. It was first published in the Harvard College magazine, ''Wake''. The play's main characters are Santa Claus, his family (Woman and Child), Death, and Mob. At the outset of the play, Santa Claus's family has disintegrated due to their lust for knowledge (Science). After a series of events, however, Santa Claus's faith in love and his rejection of the materialism and disappointment he associates with Science are reaffirmed, and he is reunited with Woman and Child.

Name and capitalization

Cummings' publishers and others have often echoed the unconventionalorthography

An orthography is a set of conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, hyphenation, capitalization, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation.

Most transnational languages in the modern period have a writing system, and mos ...

in his poetry by writing his name in lower case. Cummings himself used both the lowercase and capitalized versions, though he most often signed his name with capitals.

The use of lower case for his initials was popularized in part by the title of some books, particularly in the 1960s, printing his name in lower case on the cover and spine. In the preface to ''E. E. Cummings: The Growth of a Writer'' by Norman Friedman, critic Harry T. Moore notes Cummings "had his name put legally into lower case, and in his later books the titles and his name were always in lower case". According to Cummings' widow, however, this is incorrect. She wrote to Friedman: "You should not have allowed H. Moore to make such a stupid & childish statement about Cummings & his signature." On February 27, 1951, Cummings wrote to his French translator D. Jon Grossman that he preferred the use of upper case for the particular edition they were working on. One Cummings scholar believes that on the rare occasions that Cummings signed his name in all lower case, he may have intended it as a gesture of humility, not as an indication that it was the preferred orthography for others to use. Additionally, ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', which prescribes favoring non-standard capitalization of names in accordance with the bearer's strongly stated preference, notes "E. E. Cummings can be safely capitalized; it was one of his publishers, not he himself, who lowercased his name."

Adaptations

In 1943, modern dancer and choreographerJean Erdman

Jean Erdman (February 20, 1916 – May 4, 2020) was an American dancer and choreographer of modern dance as well as an avant-garde theater director.

Biography Early years and background

Erdman was born in Honolulu. Erdman's father, John Piney ...

presented "The Transformations of Medusa, Forever and Sunsmell" with a commissioned score by John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

and a spoken text from the title poem by E. E. Cummings, sponsored by the Arts Club of Chicago

Arts Club of Chicago is a private club and public exhibition space located in the Near North Side community area of Chicago in Cook County, Illinois, United States, a block east of the Magnificent Mile, that exhibits international contemporar ...

. Erdman also choreographed "Twenty Poems" (1960), a cycle of E. E. Cummings' poems for eight dancers and one actor, with a commissioned score by Teiji Ito

was a Japanese composer and performer. He is best known for his scores for the avant-garde films by Maya Deren.

Early life

Ito was born in Tokyo, Japan to a theatrical family. His mother, Teiko Ono, was a dancer and his father, Yuji Ito, was a ...

. It was performed in the round at the Circle in the Square Theatre

The Circle in the Square Theatre is a Broadway theater at 235 West 50th Street, in the basement of Paramount Plaza, in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It is one of two Broadway theaters that use a thrust stage that extends ...

in Greenwich Village.

Numerous composers have set Cummings' poems to music:

* In 1961, Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

composed ''cummings ist der dichter'' from poems by E. E. Cummings.

* Aribert Reimann

Aribert Reimann (born 4 March 1936) is a German composer, pianist and accompanist, known especially for his literary operas. His version of Shakespeare's ''King Lear'', the opera ''Lear (opera), Lear'', was written at the suggestion of Dietrich F ...

set Cummings to music in "Impression IV" (1961) for soprano and piano.

* Morton Feldman

Morton Feldman (January 12, 1926 – September 3, 1987) was an American composer. A major figure in 20th-century classical music, Feldman was a pioneer of indeterminate music, a development associated with the experimental New York School ...

(1926–1987) in 1951 composed "4 Songs to e.e. cummings" for soprano, piano and cello, using material from Cummings' "50 poems" of 1940: "!Blac", "Air", "(Sitting In A Tree-)" and "(Moan)".

* The Icelandic singer Björk

Björk Guðmundsdóttir ( , ; born 21 November 1965), known mononymously as Björk, is an Icelandic singer, songwriter, composer, record producer, and actress. Noted for her distinct three-octave vocal range and eccentric persona, she has de ...

used lines from Cummings' poem "I Will Wade Out" for the lyrics of "Sun in My Mouth" on her 2001 album '' Vespertine''. On her next album, '' Medúlla'' (2004), Björk used his poem "It May Not Always Be So" as the lyrics for the song "Sonnets/Unrealities XI".

* The American composer Eric Whitacre

Eric Edward Whitacre (born January2, 1970) is an American composer, conductor, and speaker best known for his choral music. In March2016, he was appointed as Los Angeles Master Chorale's first artist-in-residence at the Walt Disney Concert Hall. ...

wrote a cycle of works for choir titled ''The City and the Sea'', which consists of five poems by Cummings set to music. He also wrote music for “little tree” and “i carry your heart,” among others.

* Others who have composed settings for his poems include Dominic Argento

Dominick Argento (October 27, 1927 – February 20, 2019) was an American composer known for his lyric operatic and choral music. Among his best known pieces are the operas '' Postcard from Morocco'', '' Miss Havisham's Fire'', ''The Masque of An ...

, William Bergsma, Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first America ...

, Marc Blitzstein

Marcus Samuel Blitzstein (March 2, 1905January 22, 1964), was an American composer, lyricist, and librettist. He won national attention in 1937 when his pro-union musical ''The Cradle Will Rock'', directed by Orson Welles, was shut down by the Wo ...

, John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

, Romeo Cascarino

Romeo Cascarino (September 28, 1922 – January 8, 2002) was an American composer of classical music.

Cascarino was born in Philadelphia on September 28, 1922 and died in Norristown, Pennsylvania on January 8, 2002. He graduated from South Phil ...

, Aaron Copland, Serge de Gastyne

Serge Benoist de Gastyne (July 27, 1930 – July 24, 1992) was an American composer and pianist born in Paris, France. After fighting with the French Resistance forces in World War II, he came to the United States and attended the University of ...

, David Diamond, John Duke, Margaret Garwood

Margaret Garwood (March 22, 1927, Haddonfield, New Jersey – May 3, 2015, Philadelphia) was an American composer who is best known for her operas.

She turned into composition relatively late in her life, at age 35. She stated that through composi ...

, Daron Hagen, Michael Hedges, Timothy Hoekman

Timothy is a masculine name. It comes from the Greek name ( Timόtheos) meaning "honouring God", "in God's honour", or "honoured by God". Timothy (and its variations) is a common name in several countries.

People Given name

* Timothy (given name) ...

, Richard Hundley

Richard Albert Hundley (September 1, 1931 – February 25, 2018) was an American pianist and composer of art songs for voice and piano.

Early life

Hundley was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. When he was seven years old he moved to his paternal grand ...

, Barbara Kolb

Barbara Kolb (born February 10, 1939) is an American composer. Her music uses sound masses and often creates vertical structures through simultaneous rhythmic or melodic units ( motifs or figures). Kolb's musical style can be identified by her use ...

, Leonard Lehrman

Leonard Jordan Lehrman is an American composer who was born in Kansas, on August 20, 1949, and grew up in Roslyn, New York. Since August 3, 1999, he has resided in Valley Stream, New York.

His teachers included Lenore Anhalt, Elie Siegmeister, Ol ...

, Robert Manno

Robert Manno (born 1944, Bryn Mawr, Pa) is the composer of numerous chamber and orchestral works, song cycles and solo piano and choral works. The Atlanta Audio Society has called him "a composer of serious music of considerable depth and spiritual ...

, Salvatore Martirano

Salvatore Giovanni Martirano (January 12, 1927 – November 17, 1995) was an American composer of contemporary classical music. Born in Yonkers, New York, he taught for many years at the University of Illinois. He also worked in electronic music a ...

, William Mayer, John Musto

John Musto (born 1954) is an American composer and pianist. As a composer, he is active in opera, orchestral and chamber music, song, vocal ensemble, and solo piano works. As a pianist, he performs frequently as a soloist, alone and with orchest ...

, Paul Nordoff

Paul Nordoff (June 6, 1909 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – January 18, 1977 in Herdecke, North Rhine-Westphalia, West Germany) was an American composer and music therapist, anthroposophist and initiator of the Nordoff-Robbins method of music th ...

, Tobias Picker, Vincent Persichetti

Vincent Ludwig Persichetti (June 6, 1915 – August 14, 1987) was an American composer, teacher, and pianist. An important musical educator and writer, he was known for his integration of various new ideas in musical composition into his own wo ...

, Ned Rorem, Peter Schickele, Elie Siegmeister

Elie Siegmeister (also published under pseudonym L. E. Swift; January 15, 1909 in New York City – March 10, 1991 in Manhasset, New York) was an American composer, educator and author.

Early life and education

Elie Siegmeister was born January 15 ...

, Ann Loomis Silsbee

Ann Loomis Silsbee (21 July 1930 - 28 August 2003) was an American composer and poet who composed two operas, published three books of poetry, and received several awards, commissions, and fellowships.

Silsbee was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. ...

, Aki Takase, Hugo Weisgall, Dan Welcher, and James Yannatos

James Yannatos (March 13, 1929 – October 19, 2011) was a composer, conductor, violinist and teacher. He was a senior lecturer at Harvard University until his retirement in 2009.

, among many others.

Awards

During his lifetime, Cummings received numerous awards in recognition of his work, including: *Dial Award

The Dial Award was presented annually by the Dial Corporation

Henkel Corporation, doing business as Henkel North American Consumer Goods, and formerly The Dial Corporation, is an American company based in Stamford, Connecticut. It is a manufa ...

(1925)

* Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the ar ...

(1933)

* Shelley Memorial Award for Poetry (1945)

* Harriet Monroe Prize from ''Poetry'' magazine (1950)

* Fellowship of American Academy of Poets

The Academy of American Poets is a national, member-supported organization that promotes poets and the art of poetry. The nonprofit organization was incorporated in the state of New York in 1934. It fosters the readership of poetry through outreac ...

(1950)

* Guggenheim Fellowship (1951)

* Charles Eliot Norton Professorship at Harvard (1952–1953)

* Special citation from the National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The Nat ...

Committee for his ''Poems, 1923–1954'' (1957)

* Bollingen Prize in Poetry (1958)

* Boston Arts Festival Award (1957)

* Two-year Ford Foundation grant of $15,000 (1959)

Books

* '' CIOPW'' (1931), art works

*''i—six nonlectures'' (1953),

* '' CIOPW'' (1931), art works

*''i—six nonlectures'' (1953), Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. After the retirem ...

Prose books

* ''The Enormous Room

''The Enormous Room (The Green-Eyed Stores)'' is a 1922 autobiographical novel by the poet and novelist E. E. Cummings about his temporary imprisonment in France during World War I.

Background

Cummings served as an ambulance driver during the wa ...

'' (1922)

* ''EIMI Eimi may refer to:

* EIMI, a 1933 book by E. E. Cummings about a 1931 trip to the Soviet Union

* ''eimì'', an Ancient Greek verbs meaning "to be"

* Kuwaiti Persian

Kuwaiti Persian, known in Kuwait as ʿīmi (sometimes spelled Eimi)Written in A ...

'' (1933), Soviet travelogue

* ''Fairy Tales

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic, enchantments, and mythical or fanciful beings. In most cult ...

'' (1965), collection of short stories

Poetry

* ''Tulips and Chimneys

''Tulips and Chimneys'' is the first collection of poetry by E. E. Cummings, published in 1923.

Description

This collection is the first dedicated exclusively to Cummings's poetry;is 5

''is 5'' is a collection of poetry by E. E. Cummings, published in 1926. It contains 88 poems, divided into five sections.

The collection includes a number of satirical and anti-war poems, perhaps influenced by Cummings' time spent as an ambul ...

'' (1926)

* ''ViVa'' (1931)

* '' No Thanks'' (1935)

* ''Collected Poems'' (1938)

* ''50 Poems'' (1940)

* '' 1 × 1'' (1944)

* ''XAIPE: Seventy-One Poems'' (1950)

* ''Poems, 1923–1954'' (1954)

* ''95 Poems'' (1958)

* ''73 Poems'' (1963, posthumous)

* ''Etcetera: The Unpublished Poems'' (1983)

* ''Complete Poems, 1904–1962'', edited by George James Firmage (2008), Liveright

* ''Erotic Poems'', edited by George James Firmage (2010), Norton

Plays

* '' HIM'' (1927) * '' Santa Claus: A Morality'' (1946)References

Citations

General and cited references

* * Friedman, Norman (editor), ''E. E. Cummings: A Collection of Critical Essays''. * Friedman, Norman, ''E. E. Cummings: The Art of His Poetry''. * *Further reading

* * Galgano, Andrea, ''La furiosa ricerca di Edward E. Cummings'', in ''Mosaico'', Roma, Aracne, 2013, pp. 441–444 * Heusser, Martin. ''I Am My Writing: The Poetry of E.E. Cummings''. Tübingen: Stauffenburg, 1997. * Hutchinson, Hazel. ''The War That Used Up Words: American Writers and the First World War''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015. * James, George, ''E. E. Cummings: A Bibliography''. * McBride, Katharine, ''A Concordance to the Complete Poems of E.E.Cummings''. * Mott, Christopher.The Cummings Line on Race"

''Spring: The Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society'', vol. 4, pp. 71–75, Fall 1995. * Norman, Charles, ''E. E. Cummings: The Magic-Maker'', Boston, Little Brown, 1972. *

External links

* * * *E. E. Cummings, Lifelong Unitarian

Biography of Cummings and his relationship with Unitarianism

E.E. Cummings Personal Library

at

LibraryThing

LibraryThing is a social cataloging web application for storing and sharing book catalogs and various types of book metadata. It is used by authors, individuals, libraries, and publishers.

Based in Portland, Maine, LibraryThing was developed by ...

Papers of E. E. Cummings

at the Houghton Library at

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

E. E. Cummings Collection

at the Harry Ransom Center at the

University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

Poems by E. E. Cummings at PoetryFoundation.org

* ttp://faculty.gvsu.edu/websterm/cummings/ ''SPRING'':The Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society

Modern American Poetry

E. E. Cummings

at

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

Authorities – with 202 catalog records

Biography and poems of E. E. Cummings at Poets.org

Finding aid to Edward Estlin Cummings correspondence at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cummings, E. E. 1894 births 1962 deaths 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American poets American Field Service personnel of World War I American male poets American modernist poets American Unitarians Analysands of Fritz Wittels Bollingen Prize recipients Burials at Forest Hills Cemetery (Boston) Formalist poets Harvard Advocate alumni Lost Generation writers Massachusetts Republicans Military personnel from Massachusetts Modernist writers Old Right (United States) People from Carroll County, New Hampshire People from Greenwich Village Poets from Massachusetts Sonneteers Writers from Cambridge, Massachusetts Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters