Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1887 play) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' is a four- act

In the first act, a group of friends (including Sir Danvers Carew's daughter Agnes, attorney Gabriel Utterson, and Dr. and Mrs. Lanyon) has met up at Sir Danvers' home. Dr. Lanyon brings word that Agnes' fiancé, Dr. Henry Jekyll, will be late to the gathering. He then repeats a second-hand story about a man named Hyde, who injured a child in a collision on the street. The story upsets Utterson because Jekyll recently made a new will that gives his estate to a mysterious friend named Edward Hyde. Jekyll arrives; Utterson confronts him about the will, but Jekyll refuses to consider changing it.

Jekyll tells Agnes that they should end their engagement because of sins he has committed, but will not explain. Agnes refuses to accept this, and tells Jekyll she loves him. He relents, saying that she will help him control himself, and leaves. Sir Danvers joins his daughter, and they talk about their time in

In the first act, a group of friends (including Sir Danvers Carew's daughter Agnes, attorney Gabriel Utterson, and Dr. and Mrs. Lanyon) has met up at Sir Danvers' home. Dr. Lanyon brings word that Agnes' fiancé, Dr. Henry Jekyll, will be late to the gathering. He then repeats a second-hand story about a man named Hyde, who injured a child in a collision on the street. The story upsets Utterson because Jekyll recently made a new will that gives his estate to a mysterious friend named Edward Hyde. Jekyll arrives; Utterson confronts him about the will, but Jekyll refuses to consider changing it.

Jekyll tells Agnes that they should end their engagement because of sins he has committed, but will not explain. Agnes refuses to accept this, and tells Jekyll she loves him. He relents, saying that she will help him control himself, and leaves. Sir Danvers joins his daughter, and they talk about their time in

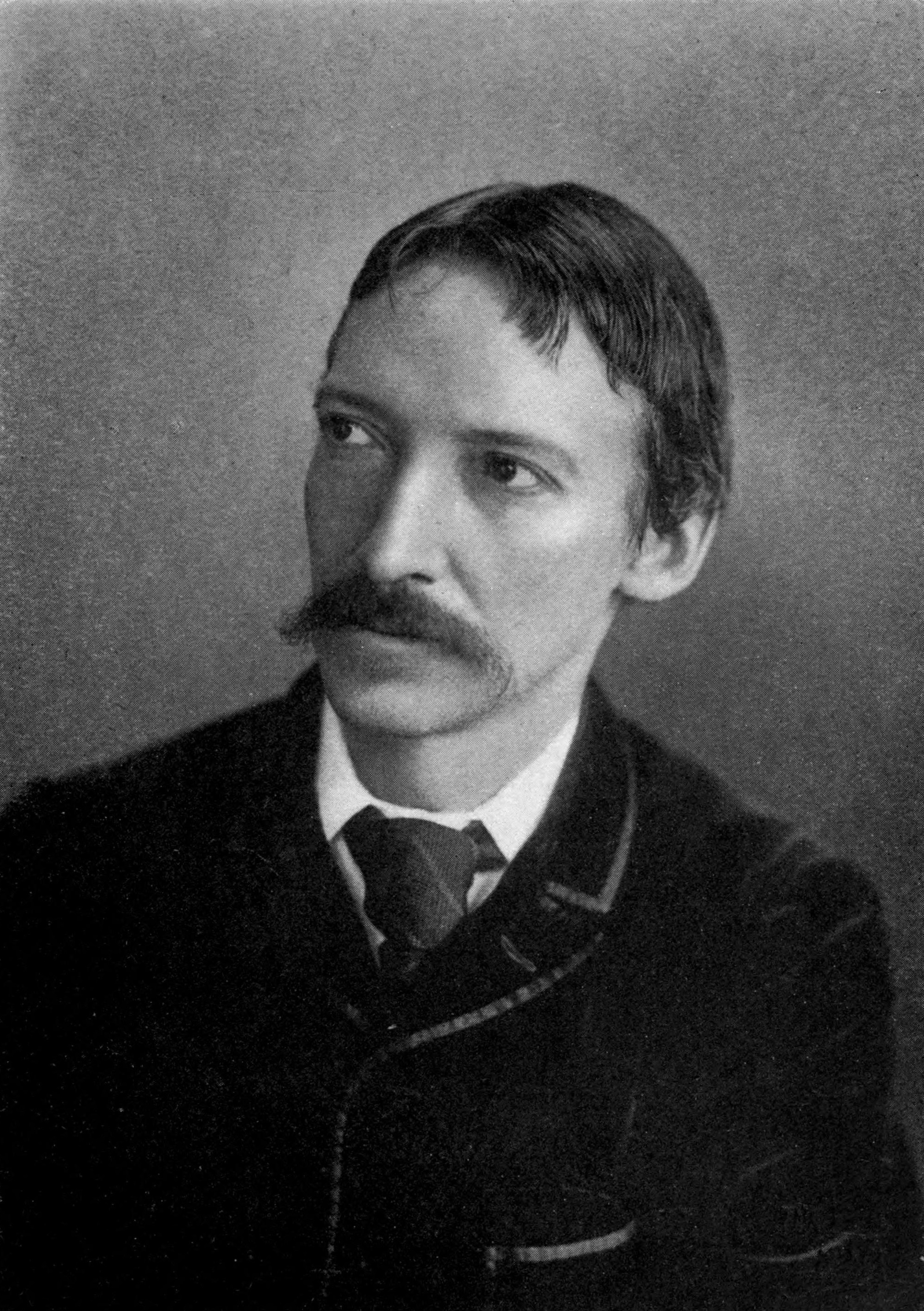

The Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson wrote ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' in 1885 when he was living in

The Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson wrote ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' in 1885 when he was living in

After just two weeks of

After just two weeks of

Mansfield also worked with Irving and Stevenson's publisher, Longmans, to block Bandmann's production and those of other competitors. In the UK, unlike the U.S., the novella had copyright protection. Longmans brought legal actions against the unauthorized versions; its efforts blocked a William Howell Poole production from opening at the Theatre Royal in

Mansfield also worked with Irving and Stevenson's publisher, Longmans, to block Bandmann's production and those of other competitors. In the UK, unlike the U.S., the novella had copyright protection. Longmans brought legal actions against the unauthorized versions; its efforts blocked a William Howell Poole production from opening at the Theatre Royal in

Although Mansfield's transformations between Jekyll and Hyde included

Although Mansfield's transformations between Jekyll and Hyde included

There were several differences between Sullivan's adaptation and Stevenson's novella. Stevenson used multiple narrators and a circular narrative (allowing material presented at the end to explain material presented at the beginning), but Sullivan wrote a

There were several differences between Sullivan's adaptation and Stevenson's novella. Stevenson used multiple narrators and a circular narrative (allowing material presented at the end to explain material presented at the beginning), but Sullivan wrote a

''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' was a milestone in the careers of Sullivan and Mansfield. Sullivan left his banking job to become a full-time writer. He wrote three more plays (none successful), several novels, and a two-volume collection of short stories, many of which have

''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' was a milestone in the careers of Sullivan and Mansfield. Sullivan left his banking job to become a full-time writer. He wrote three more plays (none successful), several novels, and a two-volume collection of short stories, many of which have

play

Play most commonly refers to:

* Play (activity), an activity done for enjoyment

* Play (theatre), a work of drama

Play may refer also to:

Computers and technology

* Google Play, a digital content service

* Play Framework, a Java framework

* Pla ...

written by Thomas Russell Sullivan

Thomas Russell Sullivan (November 21, 1849 – June 28, 1916) was an American writer. He is best known for ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1887 play), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'', an 1887 stage adaptation of ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' by R ...

in collaboration with the actor Richard Mansfield

Richard Mansfield (24 May 1857 – 30 August 1907) was an English actor-manager best known for his performances in Shakespeare plays, Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and the play '' Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde''.

Life and career

Mansfield was born ...

. It is an adaptation of ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' is a 1886 Gothic novella by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. It follows Gabriel John Utterson, a London-based legal practitioner who investigates a series of strange occurrences between his old ...

'', an 1886 novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) facts ...

by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

. The story focuses on the respected London doctor Henry Jekyll

Dr. Henry Jekyll, nicknamed in some copies of the story as Harry Jekyll, and his alternative personality, Mr. Edward Hyde, is the central character of Robert Louis Stevenson's 1886 novella ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde''. In the story, ...

and his involvement with Edward Hyde, a loathsome criminal. After Hyde murders the father of Jekyll's fiancée, Jekyll's friends discover that he and Jekyll are the same person; Jekyll has developed a potion that allows him to transform himself into Hyde and back again. When he runs out of the potion, he is trapped as Hyde and commits suicide before he can be arrested.

After reading the novella, Mansfield was intrigued by the opportunity to play a dual role

A dual role (also known as a double role) refers to one actor playing two roles in a single production. Dual roles (or a larger number of roles for an actor) may be deliberately written into a script, or may instead be a choice made during produc ...

. He secured the right to adapt

ADAPT (formerly American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today) is a United States grassroots disability rights organization with chapters in 30 states and Washington, D.C. They use nonviolent direct action in order to bring about disability just ...

the story for the stage in the United States and the United Kingdom, and asked Sullivan to write the adaptation. The play debuted in Boston in May 1887, and a revised version opened on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

in September of that year. Critics acclaimed Mansfield's performance as the dual character. The play was popular in New York and on tour, and Mansfield was invited to bring it to London. It opened there in August 1888, just before the first Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer wa ...

murders. Some press reports compared the murderer to the Jekyll-Hyde character, and Mansfield was suggested as a possible suspect. Despite significant press coverage, the London production was a financial failure. Mansfield's company continued to perform the play on tours of the U.S. until shortly before his death in 1907.

In writing the stage adaptation, Sullivan made several changes to the story; these included creating a fiancée for Jekyll and a stronger moral contrast between Jekyll and Hyde. The changes have been adopted by many subsequent adaptations, including several film versions of the story which were derived

Derive may refer to:

* Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguatio ...

from the play. The films included a 1912 adaptation directed by Lucius Henderson

Lucius Junius Henderson (June 8, 1861 – February 18, 1947) was an American silent film Film director, director and actor of the early silent period involved in more than 70 film productions.

Biography

Born in Aledo, Illinois, Henderson was a c ...

, a 1920 adaptation directed by John S. Robertson, and a 1931 adaptation directed by Rouben Mamoulian

Rouben Zachary Mamoulian ( ; hy, Ռուբէն Մամուլեան; October 8, 1897 – December 4, 1987) was an American film and theatre director.

Early life

Mamoulian was born in Tiflis, Russian Empire, to a family of Armenian descent. H ...

, which earned Fredric March

Fredric March (born Ernest Frederick McIntyre Bickel; August 31, 1897 – April 14, 1975) was an American actor, regarded as one of Hollywood's most celebrated, versatile stars of the 1930s and 1940s.Obituary ''Variety'', April 16, 1975, p ...

an Academy Award for Best Actor

The Academy Award for Best Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It is given to an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in a leading role in a film released that year. The ...

. A 1941 adaptation, directed by Victor Fleming

Victor Lonzo Fleming (February 23, 1889 – January 6, 1949) was an American film director, cinematographer, and producer. His most popular films were ''Gone with the Wind (film), Gone with the Wind'', for which he won an Academy Award for Best ...

, was a remake of the 1931 film.

Plot

In the first act, a group of friends (including Sir Danvers Carew's daughter Agnes, attorney Gabriel Utterson, and Dr. and Mrs. Lanyon) has met up at Sir Danvers' home. Dr. Lanyon brings word that Agnes' fiancé, Dr. Henry Jekyll, will be late to the gathering. He then repeats a second-hand story about a man named Hyde, who injured a child in a collision on the street. The story upsets Utterson because Jekyll recently made a new will that gives his estate to a mysterious friend named Edward Hyde. Jekyll arrives; Utterson confronts him about the will, but Jekyll refuses to consider changing it.

Jekyll tells Agnes that they should end their engagement because of sins he has committed, but will not explain. Agnes refuses to accept this, and tells Jekyll she loves him. He relents, saying that she will help him control himself, and leaves. Sir Danvers joins his daughter, and they talk about their time in

In the first act, a group of friends (including Sir Danvers Carew's daughter Agnes, attorney Gabriel Utterson, and Dr. and Mrs. Lanyon) has met up at Sir Danvers' home. Dr. Lanyon brings word that Agnes' fiancé, Dr. Henry Jekyll, will be late to the gathering. He then repeats a second-hand story about a man named Hyde, who injured a child in a collision on the street. The story upsets Utterson because Jekyll recently made a new will that gives his estate to a mysterious friend named Edward Hyde. Jekyll arrives; Utterson confronts him about the will, but Jekyll refuses to consider changing it.

Jekyll tells Agnes that they should end their engagement because of sins he has committed, but will not explain. Agnes refuses to accept this, and tells Jekyll she loves him. He relents, saying that she will help him control himself, and leaves. Sir Danvers joins his daughter, and they talk about their time in Mangalore

Mangalore (), officially known as Mangaluru, is a major port city of the Indian state of Karnataka. It is located between the Arabian Sea and the Western Ghats about west of Bangalore, the state capital, 20 km north of Karnataka–Ker ...

, India. When Hyde suddenly enters, Sir Danvers tells Agnes to leave the room. The men argue, and Hyde strangles Sir Danvers.

In the second act, Hyde fears that he will be arrested for the murder. He gives his landlady, Rebecca, money to tell visitors that he is not home. Inspector Newcome from Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

offers Rebecca more money to turn Hyde in, which she promises to do. Hyde flees to Jekyll's laboratory, where Utterson is waiting to confront the doctor about his will; he insults Utterson and leaves. Rebecca, who has followed Hyde, arrives and tells Utterson that Hyde murdered Sir Danvers. In the play's original version, the act ends with Jekyll returning to his laboratory. In later versions (revised after its premiere), the second act contains an additional scene in which Jekyll returns home; his friends think he is protecting Hyde. Agnes, who saw Hyde before her father was murdered, wants Jekyll to accompany her to provide the police with a description, and is distraught when he refuses.

In the third act, Jekyll's servant, Poole, gives Dr. Lanyon a powder and liquid with instructions from Jekyll to give them to a person who will request them. While he waits, Lanyon speaks with Newcome, Rebecca, Agnes and Mrs. Lanyon. After the others leave, Hyde arrives for the powder and liquid. After arguing with Lanyon, he mixes them into a potion and drinks it; he immediately transforms into Jekyll.

In the final act, Jekyll has begun to change into Hyde without using the potion. Although he still needs it to change back, he has exhausted his supply. Dr. Lanyon tries to help Jekyll re-create the formula, but they are unable to find an ingredient. Jekyll asks Lanyon to bring Agnes to him, but Jekyll turns into Hyde before Lanyon returns. Utterson and Newcome arrive to arrest Hyde; knowing he can no longer transform back into Jekyll, Hyde commits suicide by taking poison.

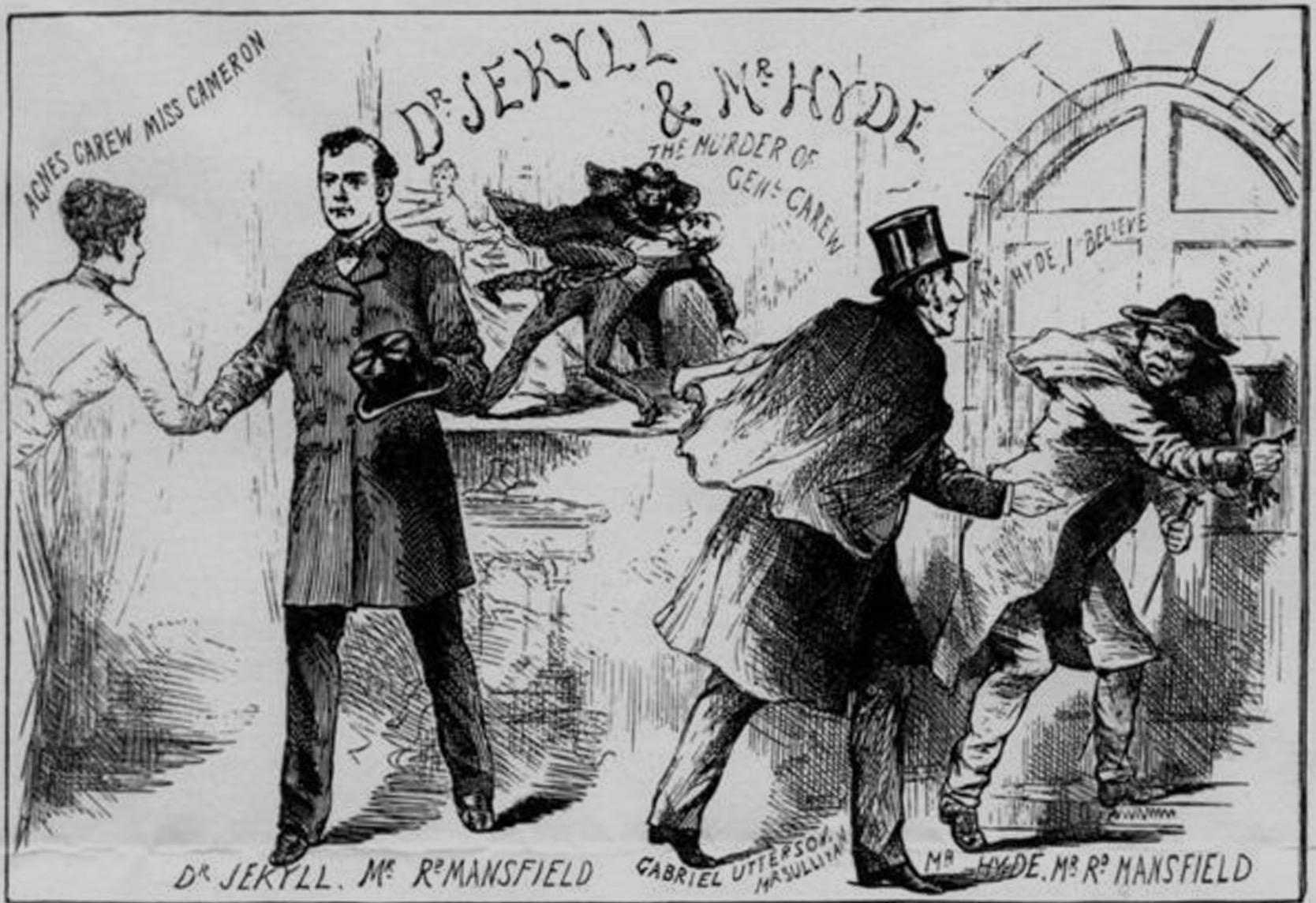

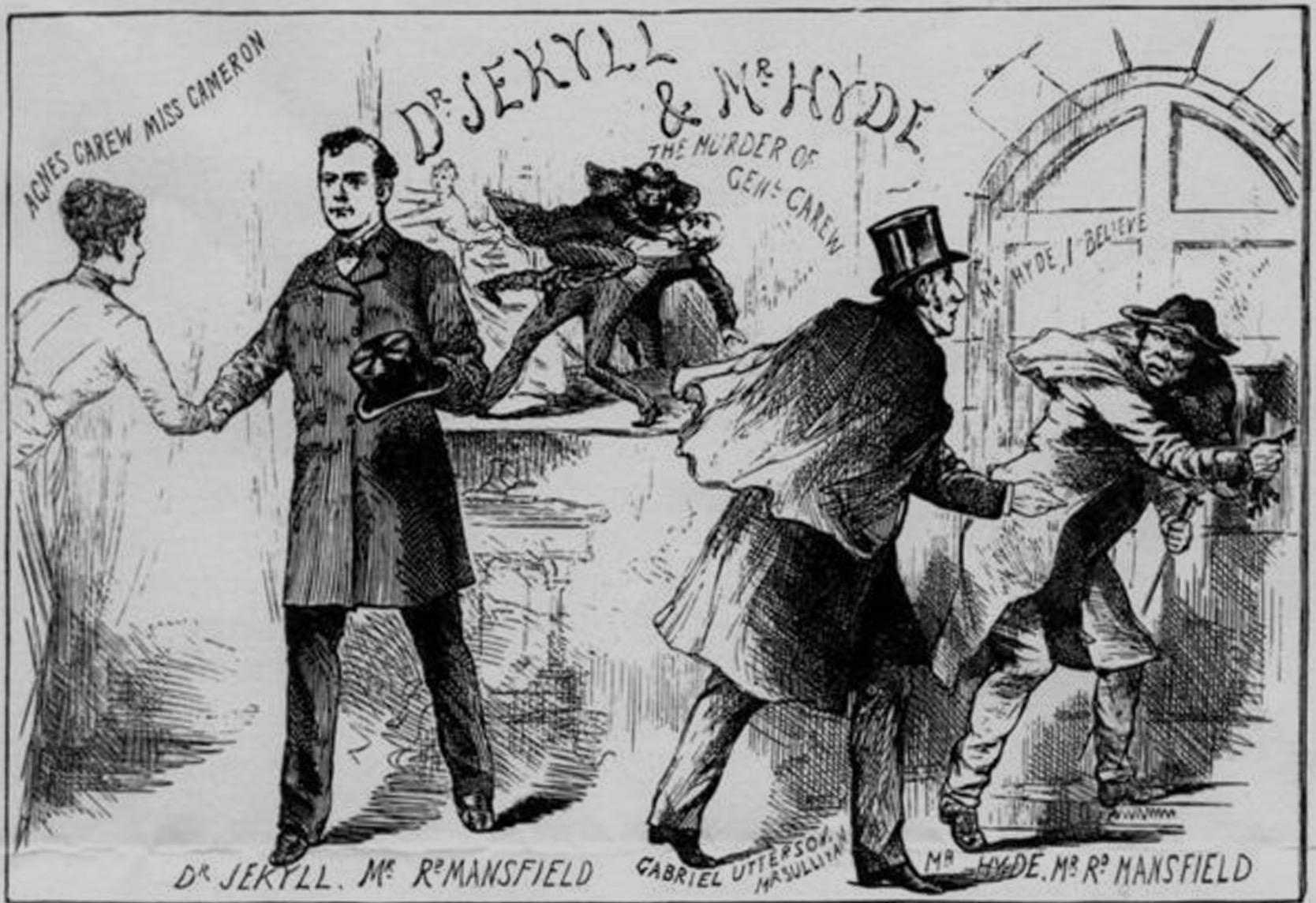

Cast and characters

The play was produced at the Boston Museum, Broadway'sMadison Square Theatre

''The Madison Square Theatre'' was a Broadway theatre in Manhattan, on the south side of 24th Street between Sixth Avenue and Broadway (which intersects Fifth Avenue near that point.) It was built in 1863, operated as a theater from 1865 to 1908, ...

and the Lyceum Theatre in London's West End with the following casts:

History

Background and writing

The Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson wrote ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' in 1885 when he was living in

The Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson wrote ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' in 1885 when he was living in Bournemouth

Bournemouth () is a coastal resort town in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole council area of Dorset, England. At the 2011 census, the town had a population of 183,491, making it the largest town in Dorset. It is situated on the Southern ...

, on England's south coast. In January 1886 the novella was published in the United Kingdom by Longmans, Green & Co. and by Charles Scribner's Sons

Charles Scribner's Sons, or simply Scribner's or Scribner, is an American publisher based in New York City, known for publishing American authors including Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kurt Vonnegut, Marjorie Kinnan Rawli ...

in the United States, where it was frequently pirated

Copyright infringement (at times referred to as piracy) is the use of works protected by copyright without permission for a usage where such permission is required, thereby infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the copyright holder, s ...

because of the lack of copyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, education ...

protection in the U.S. for works originally published in the UK. In early 1887, actor Richard Mansfield read Stevenson's novella and immediately got the idea to adapt it for the stage. Mansfield was looking for material that would help him achieve a reputation as a serious actor in the U.S., where he lived, and in England, where he had spent most of his childhood. He had played dual roles as a father and son in a New York production of the operetta

Operetta is a form of theatre and a genre of light opera. It includes spoken dialogue, songs, and dances. It is lighter than opera in terms of its music, orchestral size, length of the work, and at face value, subject matter. Apart from its s ...

''Rip Van Winkle

"Rip Van Winkle" is a short story by the American author Washington Irving, first published in 1819. It follows a Dutch-American villager in colonial America named Rip Van Winkle who meets mysterious Dutchmen, imbibes their liquor and falls aslee ...

'', and saw another acting opportunity in playing Jekyll and Hyde. He thought the role was a theatrical novelty that would showcase his talents in a favorable way.

Although U.S. copyright law would have allowed him to produce an unauthorized adaptation, Mansfield secured the American and British stage rights. Performing in Boston, he asked a local friend, Thomas Russell Sullivan, to write a script. Sullivan had previously only written in his spare time while working as a clerk for Lee, Higginson & Co., a Boston investment bank. Although he doubted that the novella would make a good play, he agreed to help Mansfield with the project, and they worked quickly to complete the adaptation before other, unauthorized versions could be staged.

First American productions

After just two weeks of

After just two weeks of rehearsal

A rehearsal is an activity in the performing arts that occurs as preparation for a performance in music, theatre, dance and related arts, such as opera, musical theatre and film production. It is undertaken as a form of practising, to ensure t ...

s, the play opened at the Boston Museum on May 9, 1887, as the first American adaptation of Stevenson's novella. On May 14, it closed for rewrites. The updated version, produced by A. M. Palmer, opened at the Madison Square Theatre on Broadway on September 12 of that year. Sullivan invited Stevenson, who had moved to the U.S. that summer; Stevenson was ill, but his wife and mother attended and congratulated Sullivan on the play. The Madison Square production closed on October 1, when Mansfield took his company on a nationwide tour. The tour began at the Chestnut Street Theatre

The Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was the first theater in the United States built by entrepreneurs solely as a venue for paying audiences.The Chestnut Street Theatre Project

The New Theatre (First Chestnut Street Theatre) ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and visited over a dozen cities, including several returns to Boston and New York. It ended at the Madison Square Theatre, where ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' was performed for a final season matinee on June 29, 1888.

In March 1888, while Mansfield's company was touring, Daniel E. Bandmann staged a competing production with the same name at Niblo's Garden

Niblo's Garden was a theater on Broadway and Crosby Street, near Prince Street, in SoHo, Manhattan, New York City. It was established in 1823 as "Columbia Garden" which in 1828 gained the name of the ''Sans Souci'' and was later the property of ...

. Bandmann's opening night (March 12) coincided with the Great Blizzard of 1888

The Great Blizzard of 1888, also known as the Great Blizzard of '88 or the Great White Hurricane (March 11–14, 1888), was one of the most severe recorded blizzards in American history. The storm paralyzed the East Coast from the Chesapeake Ba ...

, and only five theatergoers braved the storm. One of the attendees was Sullivan, who was checking his competition. Bandmann's production inspired a letter from Stevenson to the New York ''Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

'' saying that only the Mansfield version was authorized and paying him royalties

A royalty payment is a payment made by one party to another that owns a particular asset, for the right to ongoing use of that asset. Royalties are typically agreed upon as a percentage of gross or net revenues derived from the use of an asset o ...

.

1888 London production

The English actorHenry Irving

Sir Henry Irving (6 February 1838 – 13 October 1905), christened John Henry Brodribb, sometimes known as J. H. Irving, was an English stage actor in the Victorian era, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility ( ...

saw Mansfield's performance in New York and invited him to bring the play to London, where Irving managed the Lyceum Theatre in the West End. Although the play was scheduled to premiere in September 1888, Mansfield discovered that Bandmann planned to open his competing version in August, and he rushed to recall his company from vacation.

Mansfield also worked with Irving and Stevenson's publisher, Longmans, to block Bandmann's production and those of other competitors. In the UK, unlike the U.S., the novella had copyright protection. Longmans brought legal actions against the unauthorized versions; its efforts blocked a William Howell Poole production from opening at the Theatre Royal in

Mansfield also worked with Irving and Stevenson's publisher, Longmans, to block Bandmann's production and those of other competitors. In the UK, unlike the U.S., the novella had copyright protection. Longmans brought legal actions against the unauthorized versions; its efforts blocked a William Howell Poole production from opening at the Theatre Royal in Croydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an extensi ...

on July 26. That day, Fred Wright's Company B presented one performance of its adaptation at the Park Theatre in Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydf ...

before it was also closed. Bandmann had the Opera Comique

The Opera Comique was a 19th-century theatre constructed in Westminster, London, between Wych Street, Holywell Street and the Strand. It opened in 1870 and was demolished in 1902, to make way for the construction of the Aldwych and Kingsway. ...

theater reserved from August 6, but hoped to open his production earlier. Irving blocked this by reserving the theater for Mansfield's rehearsals, and Mansfield's ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' opened at the Lyceum on August 4. Bandmann went ahead with his August 6 opening, but after two performances the production was shut down because of legal action by Longmans.

Although Irving attended some of Mansfield's rehearsals, he did not remain in London for the opening. Mansfield worked with Irving's stage manager

Stage management is a broad field that is generally defined as the practice of organization and coordination of an event or theatrical production. Stage management may encompass a variety of activities including the overseeing of the rehearsal p ...

, H. J. Lovejoy, and "acting manager" Bram Stoker

Abraham Stoker (8 November 1847 – 20 April 1912) was an Irish author who is celebrated for his 1897 Gothic horror novel '' Dracula''. During his lifetime, he was better known as the personal assistant of actor Sir Henry Irving and busine ...

(who would later write the horror novel ''Dracula

''Dracula'' is a novel by Bram Stoker, published in 1897. As an epistolary novel, the narrative is related through letters, diary entries, and newspaper articles. It has no single protagonist, but opens with solicitor Jonathan Harker taking ...

'') to stage the production. He was dissatisfied with Lovejoy's stagehands and complained to a friend, the drama critic William Winter, that they were "slow" and "argumentative". Since the Lyceum crew had staged many productions and had a good reputation, Winter thought it more likely that they disliked Mansfield. Regardless of the crew's motives, Mansfield became antagonistic towards Irving during his time there.

The Lyceum production of ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' was scheduled to close on September 29, after which Mansfield intended to stage other plays. Initially, he followed this plan, introducing productions of ''Lesbia

Lesbia was the literary pseudonym used by the Roman poet Gaius Valerius Catullus ( 82–52 BC) to refer to his lover. Lesbia is traditionally identified with Clodia, the wife of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer and sister of Publius Clodius Pulc ...

'' and ''A Parisian Romance

''A Parisian Romance'' (french: Un Roman Parisien) is a play written in French by Octave Feuillet and adapted in English by Augustus R. Cazauran. Producer A. M. Palmer staged it at the Union Square Theatre on Broadway, where it debuted on Januar ...

'' at the beginning of October. However, Mansfield soon reintroduced ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' to his schedule and added performances between October 10 and October 20.

Association with Whitechapel murders

On August 7, 1888, three days after the Lyceum opening of ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'',Martha Tabram

Martha Tabram (née White; 10 May 1849 – 7 August 1888) was an English woman killed in a spate of violent murders in and around the Whitechapel district of East London between 1888 and 1891. She may have been the first victim of the still-uni ...

was discovered stabbed to death in London's Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

neighborhood. On August 31 Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann Nichols, known as Polly Nichols (née Walker; 26 August 184531 August 1888), was the first canonical victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have murdered and mutilated at least five women i ...

was found, murdered and mutilated, in the same neighborhood. Press coverage linking these and other Whitechapel murders

The Whitechapel murders were committed in or near the largely impoverished Whitechapel district in the East End of London between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891. At various points some or all of these eleven unsolved murders of women have ...

of women created a furor in London. The public and police suspected that some or all of the murders were committed by one person, who became known as Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer wa ...

. Some press reports compared the unidentified killer with the Jekyll and Hyde characters, suggesting that the Ripper led a respectable life during the day and became a murderer at night. On October 5, the City of London Police

The City of London Police is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement within the City of London, including the Middle and Inner Temples. The force responsible for law enforcement within the remainder of the London region, ou ...

received a letter suggesting that Mansfield should be considered a suspect. The letter writer, who had seen him perform as Jekyll and Hyde, thought that Mansfield could easily disguise himself and commit the murders undetected.

Mansfield attempted to defuse public concern by staging the London opening of the comedy '' Prince Karl'' as a charity performance, despite Stoker's warning that critics would view it as an attempt to obtain favorable publicity for the production. Although some press reports suggested that Mansfield stopped performing ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' in London because of the murders, financial reasons are more likely. Despite widespread publicity due to the murders and Mansfield's disputes with Bandmann, attendance was mediocre, and the production was losing money. On December 1, Mansfield's tenancy at the Lyceum ended. He left London, taking his company on a tour of England. In December they performed ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' and other plays in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

and Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gai ...

, then continued to other cities and performed other plays.

After 1888

When Mansfield left the UK in June 1889, he was deeply in debt because of production losses there. His debts included £2,675 owed to Irving, which Mansfield did not want to pay because he felt that Irving had not supported him adequately at the Lyceum. Irving sued, winning the UK performance rights to ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'', and Mansfield never performed in England again. In the U.S., the play became part of therepertory

A repertory theatre is a theatre in which a resident company presents works from a specified repertoire, usually in alternation or rotation.

United Kingdom

Annie Horniman founded the first modern repertory theatre in Manchester after withdrawing ...

of Mansfield's company and was repeatedly performed during the 1890s and early 1900s. Mansfield continued in the title role, and Beatrice Cameron continued to play Jekyll's fiancée; the actors married in 1892. In later years he staged the play less often, after becoming fearful that something would go wrong during the transformation scenes. Mansfield's company last performed the play at the New Amsterdam Theatre

The New Amsterdam Theatre is a Broadway theater on 214 West 42nd Street, at the southern end of Times Square, in the Theater District of Manhattan in New York City. One of the oldest surviving Broadway venues, the New Amsterdam was built from ...

in New York on March 21, 1907. He fell ill soon afterward, and died on August 30 of that year.

The play was closely associated with Mansfield's performance; a 1916 retrospective on adaptations of Stevenson's works indicated that Sullivan's ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' was no longer performed after Mansfield's death. Although Irving obtained the UK performance rights, he never staged the play. His son, Harry Brodribb Irving

Harry Brodribb Irving (5 August 1870 – 17 October 1919), was a British stage actor and actor-manager; the eldest son of Sir Henry Irving and his wife Florence ( née O'Callaghan), and father of designer Laurence Irving and actress Elizabeth ...

, produced a new adaptation by J. Comyns Carr

Joseph William Comyns Carr (1 March 1849 – 12 December 1916), often referred to as J. Comyns Carr, was an English drama and art critic, gallery director, author, poet, playwright and theatre manager.

Beginning his career as an art critic, Car ...

in 1910. By that time, more than a dozen other stage adaptations had appeared; the most significant was an 1897 adaptation by Luella Forepaugh and George F. Fish, made available in 1904 for stock theater performances as '' Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Or a Mis-Spent Life''.

Dramatic analysis

Jekyll-Hyde transformation

Although Mansfield's transformations between Jekyll and Hyde included

Although Mansfield's transformations between Jekyll and Hyde included lighting

Lighting or illumination is the deliberate use of light to achieve practical or aesthetic effects. Lighting includes the use of both artificial light sources like lamps and light fixtures, as well as natural illumination by capturing daylig ...

changes and makeup

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , ''asteriskos'', "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often voc ...

designed to appear different under colored filters, it was mainly accomplished by the actor's facial contortions and changes in posture and movement. As Hyde, Mansfield was hunched over with a grimacing face and claw-like hands; he spoke with a guttural voice and walked differently than he did as Jekyll. The effect was so dramatic that audiences and journalists speculated about how it was achieved. Theories included claims that Mansfield had an inflatable rubber prosthetic, that he applied chemicals, and that he had a mask hidden in a wig, which he pulled down to complete the change. Mansfield denied such theories, emphasizing that he did not use any "mechanical claptrap" in his performance.

In contrast to the novella, in which the physical transformation of Jekyll into Hyde is revealed near the end, most dramatic adaptations show it early in the play, because the audience is familiar with the story. As one of its first adapters, Sullivan worked in an environment where the transformation would still shock the audience, and he held the reveal until the third act.

Changes from the novella

There were several differences between Sullivan's adaptation and Stevenson's novella. Stevenson used multiple narrators and a circular narrative (allowing material presented at the end to explain material presented at the beginning), but Sullivan wrote a

There were several differences between Sullivan's adaptation and Stevenson's novella. Stevenson used multiple narrators and a circular narrative (allowing material presented at the end to explain material presented at the beginning), but Sullivan wrote a linear narrative

Narrative structure is a literary element generally described as the structural framework that underlies the order and manner in which a narrative is presented to a reader, listener, or viewer. The narrative text structures are the plot and the ...

in chronological order. This linear approach and the onstage action conveyed a stronger impression of realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a move ...

, eliminating uncertainties in Stevenson's narrative. Although making the story more straightforward and less ambiguous was not necessary for a theatrical adaptation, Sullivan's approach was typical of the era's stage melodrama

A modern melodrama is a dramatic work in which the plot, typically sensationalized and for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodramas typically concentrate on dialogue that is often bombastic or exces ...

s and made the material more acceptable to audiences. The stage presentation's realism also allowed Sullivan to drop the novella's scientific aspects. Although Stevenson used science to make the Jekyll-Hyde transformation plausible to readers, Sullivan could rely on the onstage transformations. In the novella, the transformation is only presented via the account of Lanyon, never as direct narration to the reader.

The playwright strengthened the contrast between Jekyll and Hyde compared to Stevenson's original; Sullivan's Hyde was more explicitly evil, and his Jekyll more conventional. In Stevenson's novella Jekyll is socially isolated and neurotic, and his motives for experimenting with the potion are ambiguous. Sullivan's adaptation changed these elements of the character. His Jekyll is socially active and mentally healthy, and his motives for creating the potion are benign; Sullivan's Jekyll tells Lanyon that his discovery will "benefit the world". Later adaptations made further changes, representing Jekyll as noble, religious or involved in charitable work. Mansfield's portrayal of Jekyll is less stereotypically good than later versions, and he thought that making the characterizations too simplistic would hurt the play's dramatic quality.

Sullivan's version added women to the story; there were no significant female characters in Stevenson's original. The presence of women (especially Jekyll's fiancée, Agnes Carew) placed Jekyll in traditional social relationships, which made him seem more normal by contemporaneous standards. Hyde behaved lecherously towards Agnes and cruelly towards his landlady, and his behavior towards women in this and later adaptations led to new interpretations of the character. In Stevenson's novella and Sullivan's play, Hyde is said to have committed unspecified crimes. Interpreters began to identify the crimes as sexual, positing sexual repression as a factor in Hyde's characterization. However, Stevenson denied that this was his understanding of the character in his original story; he said Hyde's immoralities were "cruelty and malice, and selfishness and cowardice", not sexual.

In some interpretations of the novella, the male characters represent patriarchal

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of Dominance hierarchy, dominance and Social privilege, privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical Anthropology, anthropological term for families or clans controll ...

society, with Hyde signifying its moral corruption. Other interpretations suggest that the lack of female companionship for the male characters indicates their latent homosexuality

Latent homosexuality is an erotic attraction toward members of the same sex that is not consciously experienced or expressed in overt action. This may mean a hidden inclination or potential for interest in homosexual relationships, which is eith ...

and that Hyde is engaged in homosexual activity. These interpretations are harder to apply to the play because of Sullivan's addition of female characters and heterosexual relationships.

Mansfield and his American theatre company pronounced ''Jekyll'' with a short ''e'' (/ ɛ/) instead of the long ''e'' (/iː

The close front unrounded vowel, or high front unrounded vowel, is a type of vowel sound that occurs in most spoken languages, represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet by the symbol i. It is similar to the vowel sound in the English wo ...

/) pronunciation Stevenson intended. The short ''e'' pronunciation is now used in most adaptations.

Reception

Reviewing the play's initial production at the Boston Museum, ''The Boston Post

''The Boston Post'' was a daily newspaper in New England for over a hundred years before it folded in 1956. The ''Post'' was founded in November 1831 by two prominent Boston businessmen, Charles G. Greene and William Beals.

Edwin Grozier bough ...

'' "warmly congratulated" Sullivan on his script and said that it overcame the difficulties of turning Stevenson's story into a drama with only a few flaws. Mansfield's performance was praised for drawing a clear distinction between Jekyll and Hyde, although the reviewer found his portrayal of Hyde better crafted than his portrayal of Jekyll. Audience reaction was enthusiastic, with long applause and several curtain calls for Mansfield. According to '' The Cambridge Tribune'', the audience reaction affirmed "that the play and its production were a work of genius".

The Broadway production also received positive reviews. When it opened at the Madison Square Theatre, a ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' reviewer complimented Mansfield for his acting and for overcoming the difficulty of presenting the story's allegorical

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...

material onstage. According to a ''New-York Daily Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the dom ...

'' reviewer, Mansfield gave excellent performances as Jekyll and Hyde despite a few technical production flaws. A ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' review praised Sullivan's adaptation, particularly his addition of a love interest for Jekyll, and complimented the performances of Mansfield, Cameron and Harkins.

The Lyceum production received mixed reviews, complimenting Mansfield's performance but criticizing the play as a whole. A ''Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' reviewer appreciated Mansfield's performance as Hyde and in the transformation scenes, but not as Jekyll, and called the overall play "dismal and wearisome in the extreme". According to a ''Daily Telegraph

Daily or The Daily may refer to:

Journalism

* Daily newspaper, newspaper issued on five to seven day of most weeks

* ''The Daily'' (podcast), a podcast by ''The New York Times''

* ''The Daily'' (News Corporation), a defunct US-based iPad new ...

'' review, Stevenson's story was unsuitable for drama and Sullivan had not adapted it well, but the performances of Mansfield and his company were praiseworthy. A review in '' The Saturday Review'' criticized Sullivan's adaptation, saying that it presented only one aspect of the Jekyll character from Stevenson's story. The reviewer complimented Mansfield's acting, especially in the transformation scenes, but said that his performance could not salvage the play. A review in ''The Theatre

The Theatre was an Elizabethan playhouse in Shoreditch (in Curtain Road, part of the modern London Borough of Hackney), just outside the City of London. It was the first permanent theatre ever built in England. It was built in 1576 after the ...

'' said that the play itself was not good, but it was an effective showcase for Mansfield's performance.

Sharon Aronofsky Weltman summarizes the reception for Mansfield's performance as being mostly critical of his presentation of Jekyll, but universally positive about his performance as Hyde and his handling of the transformation between the two personas.

Legacy

''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' was a milestone in the careers of Sullivan and Mansfield. Sullivan left his banking job to become a full-time writer. He wrote three more plays (none successful), several novels, and a two-volume collection of short stories, many of which have

''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde'' was a milestone in the careers of Sullivan and Mansfield. Sullivan left his banking job to become a full-time writer. He wrote three more plays (none successful), several novels, and a two-volume collection of short stories, many of which have Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

elements. Sullivan attempted one more stage collaboration with Mansfield, a drama about the Roman emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

, but they became estranged after its failure. For the actor, playing Jekyll and Hyde helped establish his reputation for dramatic roles; he had been known primarily for comedies. Mansfield continued to struggle financially (in part because of his elaborate, expensive productions) before he achieved financial stability in the mid-1890s with a string of successful tours and new productions.

Influence on later adaptations

As the most successful early adaptation of ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'', Sullivan's play influenced subsequent versions. Later adaptations followed his simplification of the narrative, addition of women characters (especially a romance for Jekyll) and highlighting of the moral contrast between Jekyll and Hyde. Most versions retain the practice of having one actor play Jekyll and Hyde, with the transformation seen by the audience. Several early film versions relied more on Sullivan's play than Stevenson's novella. TheThanhouser Company

The Thanhouser Company (later the Thanhouser Film Corporation) was one of the first motion picture studios, founded in 1909 by Edwin Thanhouser, his wife Gertrude and his brother-in-law Lloyd Lonergan. It operated in New York City until 1920, ...

produced a 1912 film version, directed by Lucius Henderson

Lucius Junius Henderson (June 8, 1861 – February 18, 1947) was an American silent film Film director, director and actor of the early silent period involved in more than 70 film productions.

Biography

Born in Aledo, Illinois, Henderson was a c ...

and starring James Cruze

James Cruze (born James Cruze Bosen; March 27, 1884 – August 3, 1942) was a silent film actor and film director.

Early years

Cruze's middle name came from the battle of Vera Cruz. He was raised in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day ...

. The one-reel film, based on Sullivan's play, may be an exception to the custom of one actor playing Jekyll and Hyde. Although Cruze was credited with a dual role, Harry Benham

Harry Benham (February 26, 1884 – July 17, 1969) was an American silent film actor.

Background

Benham was born in Valparaiso, Indiana. As a child, he and his family moved to Chicago, where he was raised and attended school. Benham had a talen ...

(who played the father of Jekyll's fiancée), said in 1963 that he had played Hyde in some scenes.

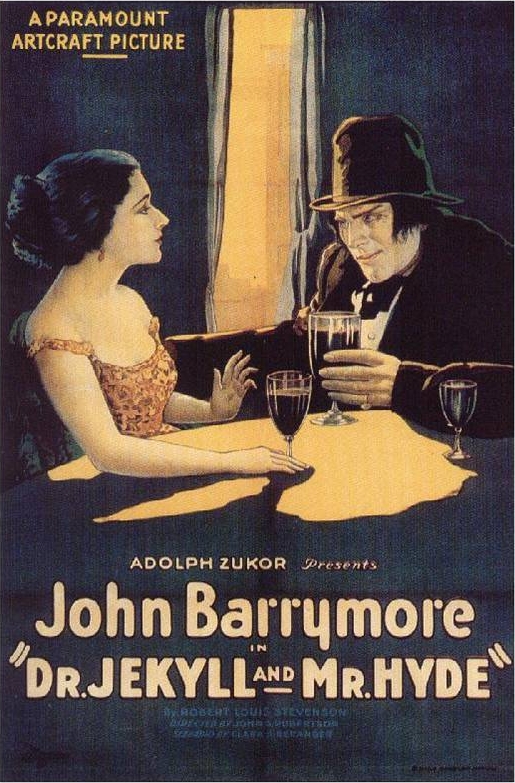

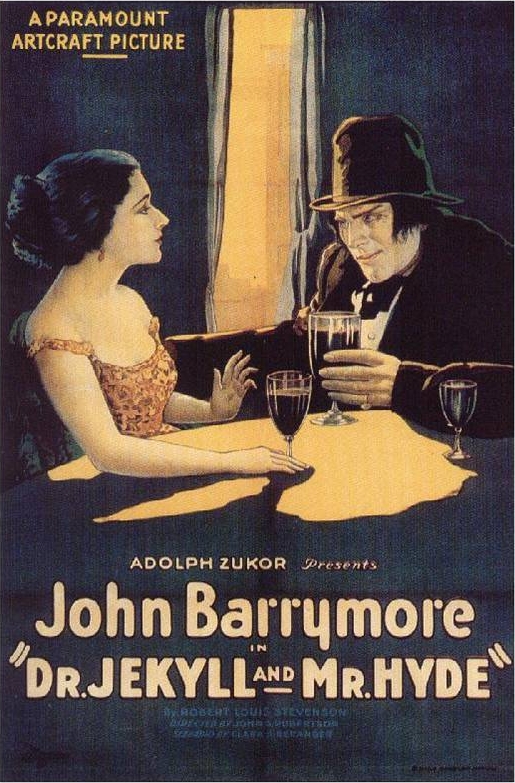

In 1920, Famous Players-Lasky

Famous Players-Lasky Corporation was an American motion picture and distribution company formed on June 28, 1916, from the merger of Adolph Zukor's Famous Players Film Company—originally formed by Zukor as Famous Players in Famous Plays—and t ...

produced a feature-length version directed by John S. Robertson. John Barrymore

John Barrymore (born John Sidney Blyth; February 14 or 15, 1882 – May 29, 1942) was an American actor on stage, screen and radio. A member of the Drew and Barrymore theatrical families, he initially tried to avoid the stage, and briefly att ...

starred as Jekyll and Hyde, with Martha Mansfield

Martha Mansfield (born Martha Ehrlich; July 14, 1899 – November 30, 1923) was an American actress in silent films and vaudeville stage plays.

Early life

She was born in New York City to Maurice and Harriett Gibson Ehrlich. She had a younger sis ...

as his fiancée. Clara Beranger

Clara Beranger (' Strouse; January 14, 1886 – September 10, 1956) was an American screenwriter of the silent film era and a member of the original faculty of the USC School of Cinematic Arts.

Biography

Beranger was born Clara Strouse in Balti ...

's script followed Sullivan's play in having Jekyll engaged to Sir Carew's daughter, but also added a relationship between Hyde and an Italian dancer (played by Nita Naldi

Nita Naldi (born Mary Nonna Dooley; In this reference Naldi's birth name Nonna is mistakenly cited “Donna”. Naldi's birthname in this reference is also incorrectly cited as “Donna”. November 13, 1894 – February 17, 1961) was an Ameri ...

). The addition of a female companion for Hyde became a feature of many later adaptations. Weltman says the design for Hyde's residence in the movie may have been influenced by Mansfield's set decoration choices, based on descriptions given in contemporary reviews of the play.

The first sound film based on Sullivan's play was a 1931 version, produced and directed by Rouben Mamoulian

Rouben Zachary Mamoulian ( ; hy, Ռուբէն Մամուլեան; October 8, 1897 – December 4, 1987) was an American film and theatre director.

Early life

Mamoulian was born in Tiflis, Russian Empire, to a family of Armenian descent. H ...

and distributed by Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation is an American film and television production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the main namesake division of Paramount Global (formerly ViacomCBS). It is the fifth-oldes ...

. The film's writers, Samuel Hoffenstein

Samuel "Sam" Hoffenstein (8 October 1890 - 6 October 1947) was a screenwriter and a musical composer. Born in Russia, he emigrated to the United States and began a career in New York City as a newspaper writer and in the entertainment business. In ...

and Percy Heath

Percy Heath (April 30, 1923 – April 28, 2005) was an American jazz bassist, brother of saxophonist Jimmy Heath and drummer Albert Heath, with whom he formed the Heath Brothers in 1975. Heath played with the Modern Jazz Quartet throughout ...

, followed much of Sullivan's storyline. Their screenplay adds a female companion for Hyde similar to Robertson's 1920 version, but Hyde murders her, a plot point that Weltman believes was influenced by the real-world association of the play with Jack the Ripper. Hoffenstein and Heath were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay

The Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay is the Academy Award for the best screenplay adapted from previously established material. The most frequently adapted media are novels, but other adapted narrative formats include stage plays, musica ...

, and the cinematographer Karl Struss

Karl Struss, A.S.C. (November 30, 1886 – December 15, 1981) was an American photographer and a cinematographer of the 1900s through the 1950s. He was also one of the earliest pioneers of 3-D films. While he mostly worked on films, such as F. ...

was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Cinematography

The Academy Award for Best Cinematography is an Academy Award awarded each year to a cinematographer for work on one particular motion picture.

History

In its first film season, 1927–28, this award (like others such as the acting awards) ...

. Fredric March

Fredric March (born Ernest Frederick McIntyre Bickel; August 31, 1897 – April 14, 1975) was an American actor, regarded as one of Hollywood's most celebrated, versatile stars of the 1930s and 1940s.Obituary ''Variety'', April 16, 1975, p ...

won the Academy Award for Best Actor

The Academy Award for Best Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It is given to an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in a leading role in a film released that year. The ...

for his portrayal of Jekyll and Hyde.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

released a 1941 film which was a remake of Mamoulian's 1931 film. Victor Fleming

Victor Lonzo Fleming (February 23, 1889 – January 6, 1949) was an American film director, cinematographer, and producer. His most popular films were ''Gone with the Wind (film), Gone with the Wind'', for which he won an Academy Award for Best ...

directed, and Spencer Tracy

Spencer Bonaventure Tracy (April 5, 1900 – June 10, 1967) was an American actor. He was known for his natural performing style and versatility. One of the major stars of Hollywood's Golden Age, Tracy was the first actor to win two cons ...

starred. This version was nominated for three Academy Awards: Joseph Ruttenberg

Joseph Ruttenberg, A.S.C. (July 4, 1889 – May 1, 1983) was a Ukrainian-born American photojournalist and cinematographer.

Ruttenberg was accomplished at winning accolades. At MGM, Ruttenberg was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Cinema ...

for Best Cinematography, Black-and-White; Harold F. Kress

Harold Frank Kress (June 26, 1913 – September 18, 1999) was an American film editor with more than fifty feature film credits; he also directed several feature films in the early 1950s. He won the Academy Award for Best Film Editing for '' How ...

for Best Film Editing, and Franz Waxman

Franz Waxman (né Wachsmann; December 24, 1906February 24, 1967) was a German-born composer and conductor of Jewish descent, known primarily for his work in the film music genre. His film scores include ''Bride of Frankenstein'', '' Rebecca'', ...

for Best Score of a Dramatic Picture.

According to the film historian Denis Meikle, Robertson, Mamoulian, and Fleming's films followed a pattern set by Sullivan's play: making Hyde's evil sexual and the Jekyll-Hyde transformation central to the performance. Meikle views this as a deterioration of Stevenson's original narrative initiated by Sullivan. The literary scholar Edwin M. Eigner says of the play and movies based on it that "each daptationdid its bit to coarsen Stevenson's ideas". Weltman says the play's association with Jack the Ripper also affected many adaptions, such as the 1990 Broadway musical ''Jekyll & Hyde

''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' is a 1886 Gothic novella by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. It follows Gabriel John Utterson, a London-based legal practitioner who investigates a series of strange occurrences between his old ...

'' and the 1971 film ''Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde

''Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde'' is a 1971 British horror film directed by Roy Ward Baker based on the 1886 novella ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' by Robert Louis Stevenson. The film was made by British studio Hammer Film Productions ...

''. However, many later adaptations diverged from the model established by Sullivan and the early films; some returned to Stevenson's novella, and others spun new variations from aspects of earlier versions.

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde (1887 play) 1887 plays Plays based on Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde Broadway plays West End plays Plays based on novels American plays adapted into films Science fiction theatre