Doug Anthony on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Douglas Anthony, (31 December 192920 December 2020) was an Australian politician. He served as leader of the

His first speech in this portfolio was made regarding the wheat price in Australia. 1966–67 had yielded a smaller amount than the 1965–66 season, and accordingly the price of wheat had to be raised. Controversially, in May 1968, Anthony initiated a payout of $21 million to offset the

His first speech in this portfolio was made regarding the wheat price in Australia. 1966–67 had yielded a smaller amount than the 1965–66 season, and accordingly the price of wheat had to be raised. Controversially, in May 1968, Anthony initiated a payout of $21 million to offset the

By mid-1969, it was thought that John McEwen, leader of the Country Party since 1958, was going to retire sometime in late 1970. The three members of the party considered to have the greatest chance of succeeding McEwen as leader were Anthony, Shipping Minister Ian Sinclair and Interior Minister

By mid-1969, it was thought that John McEwen, leader of the Country Party since 1958, was going to retire sometime in late 1970. The three members of the party considered to have the greatest chance of succeeding McEwen as leader were Anthony, Shipping Minister Ian Sinclair and Interior Minister

Anthony had a much better working relationship with

Anthony had a much better working relationship with

National Party of Australia

The National Party of Australia, also known as The Nationals or The Nats, is an Australian political party. Traditionally representing graziers, farmers, and regional voters generally, it began as the Australian Country Party in 1920 at a fed ...

from 1971 to 1984 and was the second and longest-serving Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

, holding the position under John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

(1971), William McMahon

Sir William McMahon (23 February 190831 March 1988) was an Australian politician who served as the 20th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1971 to 1972 as leader of the Liberal Party. He was a government minister for over 21 years, ...

(1971–1972) and Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

(1975–1983).

Anthony was born in Murwillumbah, New South Wales

Murwillumbah ( ) is a town in far north-eastern New South Wales, Australia, in the Tweed Shire, on the Tweed River. Sitting on the south eastern foothills of the McPherson Range in the Tweed Volcano valley, Murwillumbah is 848 km north-ea ...

, the son of federal government minister Hubert Lawrence Anthony

Hubert Lawrence "Larry" Anthony (12 March 189712 July 1957) was an Australian politician. He was a member of the Country Party and held ministerial office in the governments of Arthur Fadden and Robert Menzies, serving as Minister for Transpor ...

. He was elected to the House of Representatives at a 1957 by-election, aged 27, following his father's sudden death. He was appointed to the ministry in 1964 and in Coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

governments over the following 20 years held the portfolios of Minister for the Interior

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

(1964–1967), Primary Industry

The primary sector of the economy includes any industry involved in the extraction and production of raw materials, such as farming, logging, fishing, forestry and mining.

The primary sector tends to make up a larger portion of the economy in de ...

(1967–1971), Trade and Industry (1971–1972), Overseas Trade (1975–1977), National Resources (1975–1977), and Trade and Resources (1977–1983). Anthony was elected deputy leader of the Country Party in 1964 and succeeded John McEwen as party leader and deputy prime minister in 1971. He retired from politics at the 1984 election. His son Larry Anthony

Lawrence James Anthony (born 17 December 1961) is an Australian former politician. He was a National Party of Australia member of the Australian House of Representatives representing the Division of Richmond, New South Wales, from the March 1 ...

became the third generation of his family to enter federal parliament.

Early life

Anthony was born in Murwillumbah in northernNew South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, on 31 December 1929, the son of Jessie Anthony () and Hubert Lawrence ("Larry") Anthony, a well-known Country Party politician. Doug Anthony was educated at Murwillumbah Primary School and Murwillumbah High School

, motto_translation = I strive, I undertake, I achieve

, established =

, type = Government-funded co-educational comprehensive secondary day school

, principal = Peter Howes

, enrolment = 440

, enrolment_as_of = 2018

, teaching_staff = ...

, before attending The King's School in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

(1943–1946) and then Gatton College in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

. After graduating he took up dairy farming near Murwillumbah. In 1957 he married Margot Budd, with whom he had three children: Dougald, Jane and Larry

Larry is a masculine given name in English, derived from Lawrence or Laurence. It can be a shortened form of those names.

Larry may refer to the following:

People Arts and entertainment

* Larry D. Alexander, American artist/writer

*Larry Boon ...

.

Political career

Early career (1957–1964)

In 1957 Larry Anthony Sr., who was Postmaster-General in the Liberal–Country Party coalition government led byRobert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

, died suddenly, and Doug Anthony was elected to succeed his father in the ensuing by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election ( Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to ...

for the Division of Richmond, aged 27. He was appointed Minister for the Interior

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

in 1964 by Menzies in a reshuffle, replacing Senator John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

.

Minister for the Interior (1964–1967)

During his tenure in the Interior portfolio, there were several pushes forCanberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

to become independent and self-governing in some capacity. The Menzies government had not yet established a clear policy for Canberra's future, and Anthony stated that the city was not yet ready for self-governance. At Narrogin in August 1966, Anthony relayed to several rural communities that drought would probably soon sweep the region, and that he was prepared to take precautions to prevent as many negative effects as possible. He was unable to comment on protests that took place outside the Canberra Hotel on 2 February 1967.

Anthony was one of the leading forces against the 1967 nexus referendum, which was seeking to increase the senate's power in parliament. Senator Vince Gair

Vincent Clair Gair (25 February 190111 November 1980) was an Australian politician. He served as Premier of Queensland from 1952 until 1957, when his stormy relations with the trade union movement saw him expelled from the Labor Party. He was e ...

revived the debate around the introduction of such a law in early 1967. Anthony and the County Party decided it would be “unwise” to increase the power of the upper house.

Towards the end of his term as Minister for the Interior, Anthony supported a federal redistribution with conditions so restrictive that it favoured country seats and would increase Country Party representation. Splits within the Liberal and Country coalition were causing such issues to be raised and considered by parliament. These tensions were also fuelled by the narrow majority with which the Liberal Party was returned to power in the 1963 election; without Country Party support they could not have guaranteed parliamentary supply. In 1967 he became Minister for Primary Industry.

Minister for Primary Industry (1967–1971)

His first speech in this portfolio was made regarding the wheat price in Australia. 1966–67 had yielded a smaller amount than the 1965–66 season, and accordingly the price of wheat had to be raised. Controversially, in May 1968, Anthony initiated a payout of $21 million to offset the

His first speech in this portfolio was made regarding the wheat price in Australia. 1966–67 had yielded a smaller amount than the 1965–66 season, and accordingly the price of wheat had to be raised. Controversially, in May 1968, Anthony initiated a payout of $21 million to offset the devaluation

In macroeconomics and modern monetary policy, a devaluation is an official lowering of the value of a country's currency within a fixed exchange-rate system, in which a monetary authority formally sets a lower exchange rate of the national curre ...

of the British Pound by Prime Minister Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

; the currencies were not yet independent of each other. Anthony's popularity in the Industry portfolio was damaged when rural production was down $450 million in 1968 and little change had occurred in the return that farmers were getting for production. Anthony worked with Prime Minister John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

to try to create as many economically viable options as possible to deal with the “wheat crisis”. Eventually quotas were introduced to limit production. When China stopped importing Australian wheat in 1971, Anthony advised against communication with the country, saying it could be “politically and commercially dangerous".

Deputy Prime Minister (1971–1972)

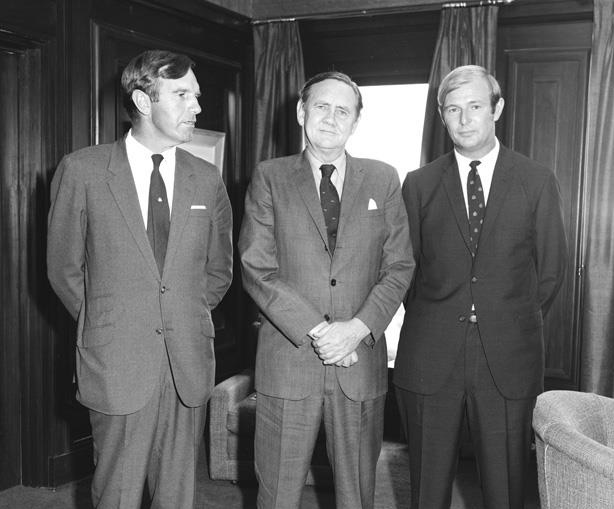

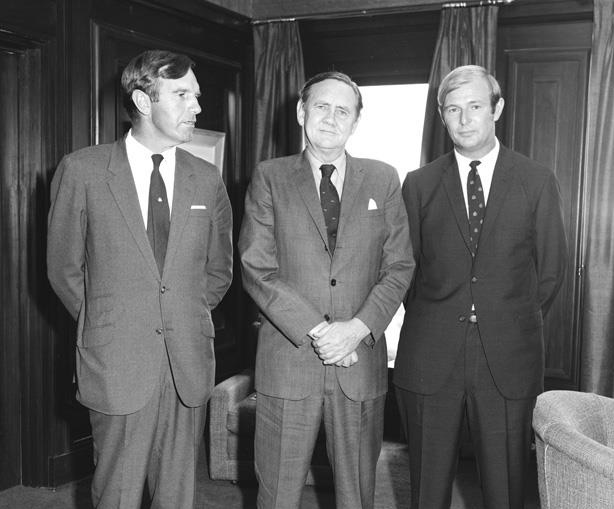

By mid-1969, it was thought that John McEwen, leader of the Country Party since 1958, was going to retire sometime in late 1970. The three members of the party considered to have the greatest chance of succeeding McEwen as leader were Anthony, Shipping Minister Ian Sinclair and Interior Minister

By mid-1969, it was thought that John McEwen, leader of the Country Party since 1958, was going to retire sometime in late 1970. The three members of the party considered to have the greatest chance of succeeding McEwen as leader were Anthony, Shipping Minister Ian Sinclair and Interior Minister Peter Nixon

Peter James Nixon AO (born 22 March 1928) is a former Australian politician and businessman. He served in the House of Representatives from 1961 to 1983, representing the Division of Gippsland as a member of the National Country Party (NCP). H ...

. When McEwen retired in 1971, Anthony was chosen as his successor, taking McEwen's old posts of Minister for Trade and Industry and Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

in the government of John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

, portfolios he retained under William McMahon

Sir William McMahon (23 February 190831 March 1988) was an Australian politician who served as the 20th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1971 to 1972 as leader of the Liberal Party. He was a government minister for over 21 years, ...

. Anthony was made a Privy Councillor

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

on 23 June 1971.

When McMahon became Prime Minister in March 1971, only a month after Anthony had taken the Deputy Prime Minister position, Anthony lost power as McMahon disliked him and the two had a poor working relationship. Anthony opposed the revaluation of the Australian dollar by McMahon in 1971–72. In mid-1972, McMahon stopped talking to Anthony and he was oblivious to many decisions that were occurring outside cabinet. When McMahon announced the 1972 election, he left Anthony in the dark and he was unaware of the date on which it would take place and the campaign techniques the coalition would use. Anthony called the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jack Marshall

Sir John Ross Marshall New Zealand Army Orders 1952/405 (5 March 1912 – 30 August 1988) was a New Zealand politician of the National Party. He entered Parliament in 1946 and was first promoted to Cabinet in 1951. After spending twelve years ...

, to find out the date, as McMahon had only informed three people of the date before approaching the Governor-General. Anthony lost faith in the government and became complacent about the defeat which became obvious in the lead up to the election in December 1972.

Opposition (1972–1975)

After McMahon's defeat in 1972, Anthony was said to favour a policy of absolute opposition to theLabor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

government of Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the h ...

. Despite that, the Country Party voted with the Labor Government on some bills, for example the 1973 expansion of state aid to under-privileged schools. Under Anthony's leadership, the party's name was changed to the National Country Party and it began contesting urban seats in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

and Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

. There was also a weakening in the party's relationship with primary producer organisations. In 1975, Anthony, along with other senior Opposition members, criticised Whitlam for not giving enough aid to Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

.

Deputy Prime Minister (1975–1983)

Anthony had a much better working relationship with

Anthony had a much better working relationship with Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

than he did with Billy Snedden

Sir Billy Mackie Snedden, (31 December 1926 – 27 June 1987) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Liberal Party from 1972 to 1975. He was also a cabinet minister from 1964 to 1972, and Speaker of the House of Repres ...

. At first, Anthony did not support Snedden's or Fraser's decisions to block parliamentary supply from the Labor Party, beginning in October 1975, though he was soon convinced otherwise. The Coalition was confirmed in power at the 1975 election, with the biggest majority government in Australian history. Though from 1975 to 1980 the Liberals won enough seats to form government in their own right, Fraser opted to retain the Coalition with the NCP. Anthony again became Deputy Prime Minister, with the portfolios of Overseas Trade and National Resources (Trade and Resources from 1977). Anthony was noted, while Prime Minister Fraser took annual Christmas holidays, for governing the country as Acting Prime Minister from a caravan in his electorate of Richmond.

In 1976, during his second term as Deputy Prime Minister, Anthony began a strong import and export relationship with Japan, particularly over oil. Anthony supported the mining and export of Australian uranium, and believed it would be an essential part of the future economy. While Acting Prime Minister in July 1976, he was the first user of the Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

–Cairns

Cairns (, ) is a city in Queensland, Australia, on the tropical north east coast of Far North Queensland. The population in June 2019 was 153,952, having grown on average 1.02% annually over the preceding five years. The city is the 5th-most-p ...

telephone line, speaking to Acting Prime Minister Sir Maori Kiki. While Acting Prime Minister in July 1979, he threatened to shut down an industrial strike in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

, stating the issue had to be resolved. The Labor Party was strongly opposed to this action and called his power as Acting Prime Minister into question. After Fraser lost office in 1983, Anthony remained as party leader (since 1974 named the National Party). The last major move as leader of the National Party that Anthony made was to explain the tensions between the Liberal and National parties in Queensland, who officially opposed each other in the October 1983 election.

Retirement and death

Anthony remained in parliament for less than a year before retiring from politics in 1984. By then, although only 55, he was the Father of the House of Representatives. He returned to his farm near Murwillumbah and generally stayed out of politics. In1996

File:1996 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: A bomb explodes at Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta, set off by a radical anti-abortionist; The center fuel tank explodes on TWA Flight 800, causing the plane to crash and killing everyone o ...

, Larry Anthony

Lawrence James Anthony (born 17 December 1961) is an Australian former politician. He was a National Party of Australia member of the Australian House of Representatives representing the Division of Richmond, New South Wales, from the March 1 ...

won his father's old seat.

In 1994, Anthony appeared in a documentary series about the Liberal Party in which he revealed that McMahon had refused to tell him beforehand the date of the 1972 election, despite Anthony being the Country Party leader. During 1999, Anthony spoke in support of Australia becoming a republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

.

Anthony died at an aged care home in Murwillumbah, on 20 December 2020, at the age of 90, 11 days before his 91st birthday. Until his death, he was the earliest-elected Country MP still alive, and along with his deputy and successor as National Party leader, Ian Sinclair, he was one of the last two surviving ministers who served in the Menzies Government and the First Holt Ministry.

Honours

In 1981 Anthony was appointed aCompanion of Honour

The Order of the Companions of Honour is an order of the Commonwealth realms. It was founded on 4 June 1917 by King George V as a reward for outstanding achievements. Founded on the same date as the Order of the British Empire, it is sometimes ...

(CH). In 1990, he was awarded the New Zealand 1990 Commemoration Medal

The New Zealand 1990 Commemoration Medal was a commemorative medal awarded in New Zealand in 1990 to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, and was awarded to approximately 3,000 people.

Background

The New Ze ...

. In 2003 he was made a Companion of the Order of Australia

The Order of Australia is an honour that recognises Australian citizens and other persons for outstanding achievement and service. It was established on 14 February 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, on the advice of the Australian Go ...

(AC) for service to the Australian Parliament, for forging the development of bi-lateral trade agreements, and for continued leadership and dedication to the social, educational, health and development needs of rural and regional communities.

See also

* Anthony family * Doug Anthony All StarsExplanatory notes

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Anthony, Doug 1929 births 1975 Australian constitutional crisis 2020 deaths 20th-century Australian politicians Australian Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Companions of the Order of Australia Deputy Prime Ministers of Australia Fellows of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering Government ministers of Australia Leaders of the National Party of Australia Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Richmond Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia National Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia People from the Northern Rivers