Dorking () is a

market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural ...

in

Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

in

South East England

South East England is one of the nine official regions of England at the first level of ITL for statistical purposes. It consists of the counties of Buckinghamshire, East Sussex, Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, Kent, Oxfordshire, Berkshi ...

, about south of

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. It is in

Mole Valley District and the

council

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

headquarters are to the east of the centre. The

High Street

High Street is a common street name for the primary business street of a city, town, or village, especially in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. It implies that it is the focal point for business, especially shopping. It is also a metonym fo ...

runs roughly east–west, parallel to the

Pipp Brook and along the northern face of an outcrop of

Lower Greensand

The Lower Greensand Group is a geological unit present across large areas of Southern England. It was deposited during the Aptian and Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous. It predominantly consists of sandstone and unconsolidated sand that were ...

. The town is surrounded on three sides by the

Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and is close to

Box Hill and

Leith Hill

Leith Hill in southern England is the highest summit of the Greensand Ridge, approximately southwest of Dorking, Surrey and southwest of central London. It reaches above sea level, and is the second highest point in southeast England, after ...

.

The earliest archaeological evidence of human activity is from the

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic ( Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymo ...

and

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

periods, and there are several

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

bowl barrow

A bowl barrow is a type of burial mound or tumulus. A barrow is a mound of earth used to cover a tomb. The bowl barrow gets its name from its resemblance to an upturned bowl. Related terms include ''cairn circle'', ''cairn ring'', ''howe'', ''ker ...

s in the local area. The town may have been the site of a staging post on

Stane Street during

Roman times, however the name 'Dorking' suggests an

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

origin for the modern settlement. A

market is thought to have been held at least weekly since early

medieval times

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

and was highly regarded for the

poultry

Poultry () are domesticated birds kept by humans for their eggs, their meat or their feathers. These birds are most typically members of the superorder Galloanserae (fowl), especially the order Galliformes (which includes chickens, qu ...

traded there. The

Dorking

Dorking () is a market town in Surrey in South East England, about south of London. It is in Mole Valley, Mole Valley District and the non-metropolitan district, council headquarters are to the east of the centre. The High Street runs roughl ...

breed of

domestic chicken

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domestication, domesticated junglefowl species, with attributes of wild species such as the grey junglefowl, grey and the Ceylon junglefowl that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster ...

is named after the town.

The local economy thrived during

Tudor times, but declined in the 17th century due to poor infrastructure and competition from neighbouring towns. During the

early modern period many inhabitants were

nonconformists, including the author,

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel '' Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

, who lived in Dorking as a child. Six of the ''

Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, ...

''

Pilgrims, including

William Mullins and his daughter

Priscilla

Priscilla is an English female given name adopted from Latin ''Prisca'', derived from ''priscus''. One suggestion is that it is intended to bestow long life on the bearer.

The name first appears in the New Testament of Christianity variously as ...

, lived in the town before setting sail for the New World.

Dorking started to expand during the 18th and 19th centuries as transport links improved and farmland to the south of the centre was released for

housebuilding. The new

turnpike

Turnpike often refers to:

* A type of gate, another word for a turnstile

* In the United States, a toll road

Turnpike may also refer to:

Roads United Kingdom

* A turnpike road, a principal road maintained by a turnpike trust, a body with powe ...

, and later the

railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a p ...

s, facilitated the sale of

lime produced in the town, but also attracted wealthier residents, who had had no previous connection to the area. Residential expansion continued in the first half of the 20th century, as the

Deepdene and

Denbies

Denbies is a large estate to the northwest of Dorking in Surrey, England. A farmhouse and surrounding land originally owned by John Denby was purchased in 1734 by Jonathan Tyers, the proprietor of Vauxhall Gardens in London, and converted into ...

estates began to be broken up. Further development is now constrained by the

Metropolitan Green Belt

The Metropolitan Green Belt is a statutory green belt around London, England. It comprises parts of Greater London, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent and Surrey, parts of two of the three districts of Bedfordshire and a s ...

, which encircles the town.

Toponymy

The origins and meaning of the name Dorking are uncertain.

Early spellings include ''Dorchinges'' (1086), ''Doreking'' (1138–47),

[ ''Dorkinges'' (1180),][ Both principal elements in the name are disputed. The first element may be from a personal name, ''Deorc'', or some variant, of either ]Brittonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

or Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

origin. Alternatively it may derive from the Brittonic words ''Dorce'', a river name meaning "clear, bright stream", or ''duro'', meaning a "fort", "walled town" or "gated place".[

]

Geography

Location and topography

Dorking is in central Surrey, about south of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and east of Guildford

Guildford ()

is a town in west Surrey, around southwest of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The name "Guildf ...

. It is close to the intersection of two valleys – the north-south Mole Gap (where the River Mole

The River Mole is a tributary of the River Thames in southern England. It rises in West Sussex near Gatwick Airport and flows northwest through Surrey for to the Thames at Hampton Court Palace. The river gives its name to the Surrey distri ...

cuts through the North Downs

The North Downs are a ridge of chalk hills in south east England that stretch from Farnham in Surrey to the White Cliffs of Dover in Kent. Much of the North Downs comprises two Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs): the Surrey Hills ...

) and the west–east Vale of Holmesdale

Holmesdale, also known as the Vale of Holmesdale, is a valley in South-East England that falls between the hill ranges of the North Downs and the Greensand Ridge of the Weald, in the counties of Kent and Surrey. It stretches from Folkestone o ...

(a narrow strip of low-lying land between the North Downs and the Greensand Ridge

The Greensand Ridge, also known as the Wealden Greensand is an extensive, prominent, often wooded, mixed greensand/sandstone escarpment in south-east England. Forming part of the Weald, a former dense forest in Sussex, Surrey and Kent, it r ...

).Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

bowl barrow

A bowl barrow is a type of burial mound or tumulus. A barrow is a mound of earth used to cover a tomb. The bowl barrow gets its name from its resemblance to an upturned bowl. Related terms include ''cairn circle'', ''cairn ring'', ''howe'', ''ker ...

.medieval times

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

(and may be Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

in origin).Metropolitan Green Belt

The Metropolitan Green Belt is a statutory green belt around London, England. It comprises parts of Greater London, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent and Surrey, parts of two of the three districts of Bedfordshire and a s ...

(which also covers the Glory Wood) and is bordered on three sides by the Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Several Sites of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle of ...

are close by, including the Mole Gap to Reigate Escarpment, immediately to the north. The National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

owns several properties in the area, including Box Hill,Leith Hill Tower

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

Polesden Lacey

Polesden Lacey is an Edwardian house and estate, located on the North Downs at Great Bookham, near Dorking, Surrey, England. It is owned and run by the National Trust and is one of the Trust's most popular properties.

This Regency house was ex ...

.[.]

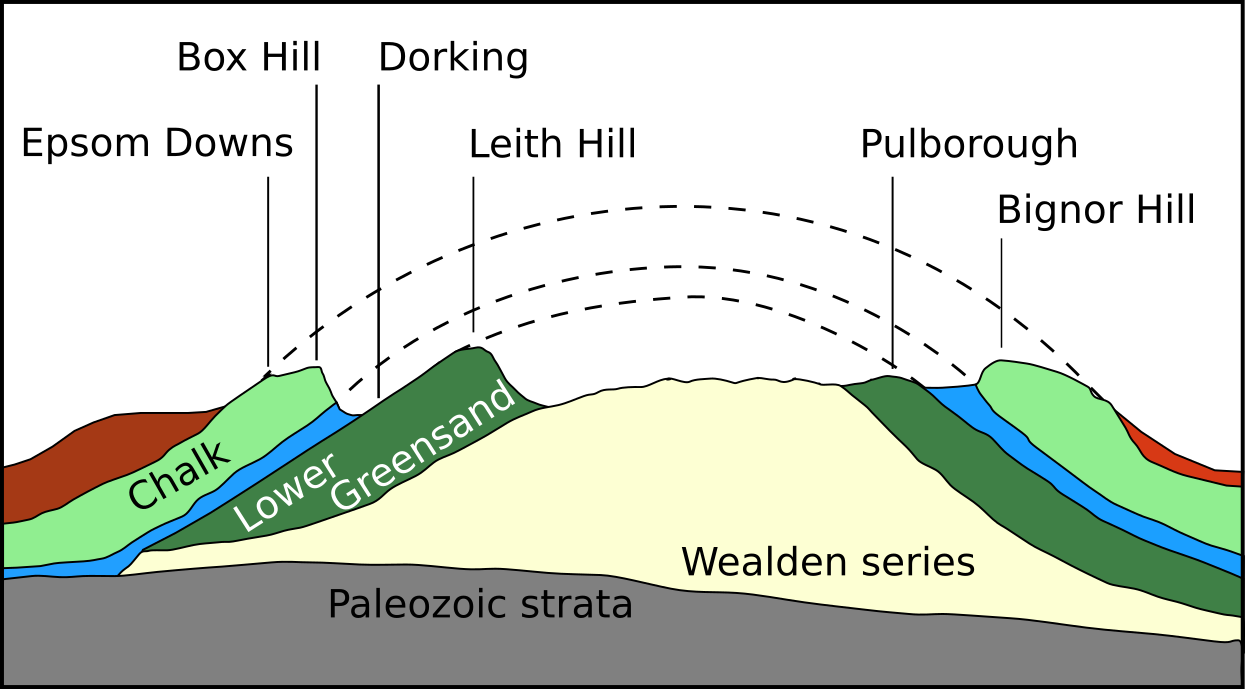

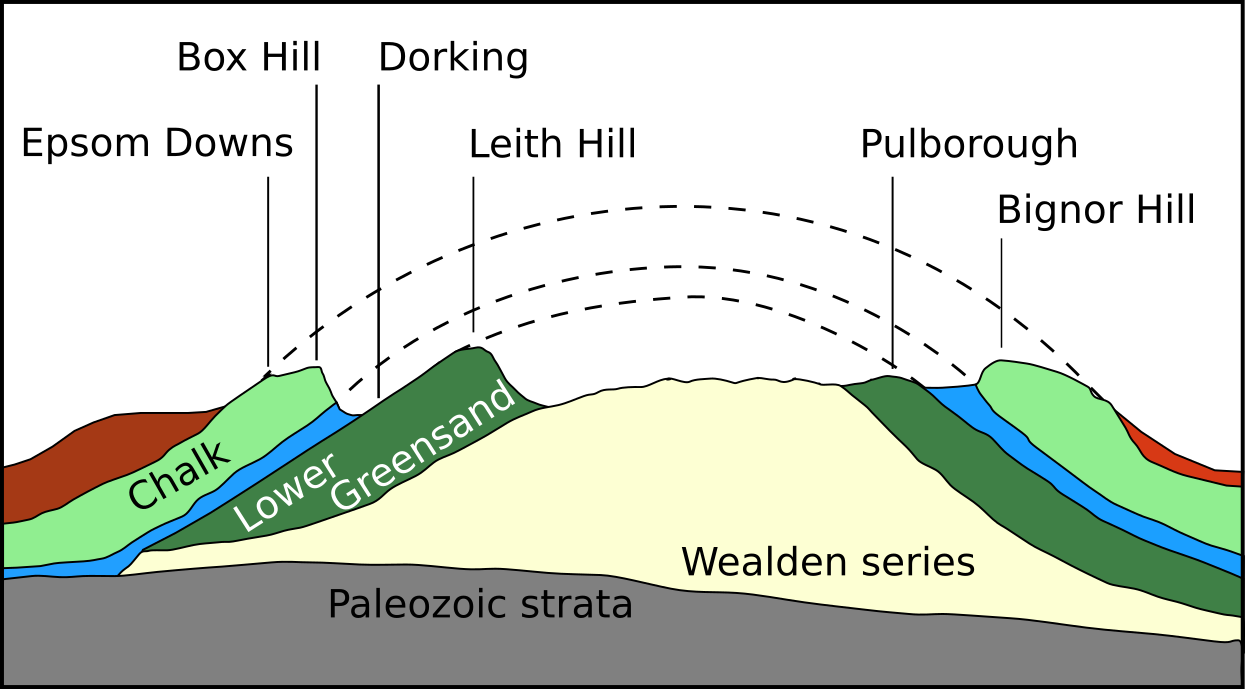

Geology

The rock

The rock strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

on which Dorking sits, belong primarily to the Lower Greensand Group

The Lower Greensand Group is a geological unit present across large areas of Southern England. It was deposited during the Aptian and Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous. It predominantly consists of sandstone and unconsolidated sand that were ...

. This group is multilayered and includes the sandy Hythe Beds, the clayey Sandgate Beds and the quartz-rich Folkestone Beds.early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145& ...

, most likely in a shallow sea with low oxygen levels. Over the subsequent 50 million years, other strata were deposited on top of the Lower Greensand, including Gault clay

The Gault Formation is a geological formation of stiff blue clay deposited in a calm, fairly deep-water marine environment during the Lower Cretaceous Period (Upper and Middle Albian). It is well exposed in the coastal cliffs at Copt Point in ...

, Upper Greensand

Greensand or green sand is a sand or sandstone which has a greenish color. This term is specifically applied to shallow marine sediment that contains noticeable quantities of rounded greenish grains. These grains are called ''glauconies'' and c ...

and the chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. C ...

of the North and South Downs.

Following the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

, the sea covering the south of England began to retreat and the land was pushed higher. The Weald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex and Kent. It has three separate parts: the sandstone "High Weald" in the ...

(the area covering modern-day south Surrey, south Kent, north Sussex and east Hampshire) was lifted by the same geological processes that created the Alps, resulting in an anticline

In structural geology, an anticline is a type of fold that is an arch-like shape and has its oldest beds at its core, whereas a syncline is the inverse of an anticline. A typical anticline is convex up in which the hinge or crest is t ...

which stretched across the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

to the Artois region of northern France. Initially an island, this dome-like structure was drained by the ancestors of the rivers which today cut through the North and South Downs, including the Mole. The dome was eroded away over the course of the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

, exposing the strata beneath and resulting in the escarpment

An escarpment is a steep slope or long cliff that forms as a result of faulting or erosion and separates two relatively level areas having different elevations.

The terms ''scarp'' and ''scarp face'' are often used interchangeably with ''esca ...

s of the Downs and the Greensand Ridge.

In Dorking, the dividing line between the Lower Greensand and Gault clay is marked by the course of the Pipp Brook. In the south of the town, the Hythe Beds take the form of iron-rich, soft, fine-grained

Granularity (also called graininess), the condition of existing in granules or grains, refers to the extent to which a material or system is composed of distinguishable pieces. It can either refer to the extent to which a larger entity is sub ...

sandstone, whereas the Sandgate Beds have a more loam

Loam (in geology and soil science) is soil composed mostly of sand ( particle size > ), silt (particle size > ), and a smaller amount of clay (particle size < ). By weight, its mineral composition is about 40–40–20% concentration of sand–si ...

y composition. The quartz-rich Folkestone Beds have a lower iron content, and contain veins of silver sand Silver sand is a fine white sand used in gardening. It consists largely of quartz particles that are not coated with iron oxides. Iron oxides colour sand from yellows to rich brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it ...

and rose-coloured ferruginous

The adjective ferruginous may mean:

* Containing iron, applied to water, oil, and other non-metals

* Having rust on the surface

* With the rust (color)

See also

* Ferrous, containing iron (for metals and alloys) or iron(II) cations

* Ferric, cont ...

sand. Running along the north bank of the Pipp Brook (with a width of around ) is the outcrop of Gault, a blue-black shaly clay, beyond which is a narrow band of Upper Greensand, a hard, grey mica-rich sandstone. In the extreme north west of the town, the marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part ...

y Lower Chalk was quarried for lime production until the early 20th century.

Ammonite fossils are found in the north of the town, including ''Stoliczkia

''Stoliczkia'' is a genus of snakes in the family Xenodermidae. The genus contains two species, both from India.

Etymology

The genus is named after Ferdinand Stoliczka, Moravian-born zoologist who later worked for the Geological Survey of India. ...

'', ''Callihoplites

''Callihoplites'' is a genus of rather evolute ammonites from the Lower Cretaceous, Late Albian

The Albian is both an age of the geologic timescale and a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest or uppermost subdivision of the ...

'', '' Acanthoceras'' and ''Euomphaloceras

''Euomphaloceras'' is an early Upper Cretaceous ammonite

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely relate ...

'' species in the Lower Chalk and ''Puzosia

''Puzosia'' is a genus of desmoceratid ammonites, and the type genus for the Puzosiinae, which lived during the middle part of the Cretaceous, from early Aptian to Maastrichtian (125.5 to 70.6 Ma). The generic name comes from the Serbian word ...

'' species in the Upper Greensand. Foraminifera

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly ...

fossils have been found in the Hythe Beds adjacent to the Horsham road, to the west of Tower Hill.

History and development

Pre-history

The earliest evidence of human activity in Dorking comes from the Mesolithic

The Mesolithic ( Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymo ...

and Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

periods and includes flint tools

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

and flakes found during construction development in South Street.ring ditch

In archaeology, a ring ditch is a trench of circular or penannular plan, cut into bedrock. They are usually identified through aerial photography either as soil marks or cropmarks. When excavated, ring ditches are usually found to be the ploughed� ...

containing two ceramic urns, was discovered in 2013 during the rebuilding of Waitrose

Waitrose & Partners (formally Waitrose Limited) is a brand of British supermarkets, founded in 1904 as Waite, Rose & Taylor, later shortened to Waitrose. It was acquired in 1937 by employee-owned retailer John Lewis Partnership, which still se ...

supermarket. Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was de ...

of hazelnut

The hazelnut is the fruit of the hazel tree and therefore includes any of the nuts deriving from species of the genus '' Corylus'', especially the nuts of the species ''Corylus avellana''. They are also known as cobnuts or filberts according ...

shells found at the base suggests that it was dug between 8625 and 8465 BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

and may have enclosed a bowl barrow

A bowl barrow is a type of burial mound or tumulus. A barrow is a mound of earth used to cover a tomb. The bowl barrow gets its name from its resemblance to an upturned bowl. Related terms include ''cairn circle'', ''cairn ring'', ''howe'', ''ker ...

. Other ditches nearby may indicate the presence of a Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

field system The study of field systems (collections of fields) in landscape history is concerned with the size, shape and orientation of a number of fields. These are often adjacent, but may be separated by a later feature.

Field systems by region Czech Republ ...

, although the date of these later earthworks is less certain. Bowl barrows from the same period have been found at the Glory Wood (to the south of the town centre),[ on Milton Heath (to the west) and on Box Hill (to the northeast).

]

Roman and Saxon

There is thought to have been a settlement at Dorking in Roman times, although its size and extent are unclear. Coins

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order t ...

from the reigns of Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania ...

(117–138 AD), Commodus

Commodus (; 31 August 161 – 31 December 192) was a Roman emperor who ruled from 177 to 192. He served jointly with his father Marcus Aurelius from 176 until the latter's death in 180, and thereafter he reigned alone until his assassination. ...

(180–192) and Claudius Gothicus

Marcus Aurelius Claudius "Gothicus" (10 May 214 – January/April 270), also known as Claudius II, was Roman emperor from 268 to 270. During his reign he fought successfully against the Alemanni and decisively defeated the Goths at the Battle ...

(214–270), as well as tiles and pottery fragments, have been found in the town.[ Stane Street, the ]Roman road

Roman roads ( la, viae Romanae ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Re ...

linking London to Chichester

Chichester () is a cathedral city and civil parish in West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publishing Date:2009. It is the only ...

, was constructed during the first century AD[ The exact course through the town is not known and no definitive archaeological evidence has been discovered for the route in the gap between the crossing of the River Mole at the Burford Bridge and ]North Holmwood

North Holmwood is a residential area on the outskirts of Dorking, in Surrey, England. The village is accessible from the A24, the village's historic heart is the road Spook Hill. The 2011 census for the broader area ''Holmwoods'' shows a populati ...

.[ A posting station is thought to have been located in the area and sites have been proposed in the town centre,]Pixham

__NOTOC__

Pixham is a chapelry ( small village) within the parish of Dorking, Surrey on the near side of the confluence of the River Mole and the Pipp Brook to its town, Dorking, which is centred 1 km (0.6 mi) southwest. The town as ...

[ and at the Burford Bridge, where the road crossed the River Mole.]Norman conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

, archaeological evidence of Saxon activity in the town centre is limited to pottery sherds

This page is a glossary of archaeology, the study of the human past from material remains.

A

B

C

D

E

F

...

.[ Probable Saxon ]cemeteries

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite or graveyard is a place where the remains of dead people are buried or otherwise interred. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek , "sleeping place") implies that the land is specifically designated as a bu ...

have been found close to Yew Tree Road (to the north of the centre) and at Vincent Lane (to the west). In 1817, the so-called "Dorking Hoard" of around 700 silver pennies, dating from the mid-8th to the late-9th centuries, was found near the source of the Pipp Brook on the northern slopes of Leith Hill.Wotton Hundred

The Hundred of Wotton, Wotton Hundred or Dorking Hundred was a hundred in Surrey, England.

The hundred comprised a south-central portion of the county, clockwise the parishes of Abinger, Wotton, Dorking, Capel and Ockley.

The area's owner ...

Leatherhead

Leatherhead is a town in the Mole Valley District of Surrey, England, about south of Central London. The settlement grew up beside a ford on the River Mole, from which its name is thought to derive. During the late Anglo-Saxon period, Leathe ...

.[

]

Governance

Dorking appears in Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

of 1086 as the Manor of ''Dorchinges''. It was held by William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

, who had assumed the lordship in 1075 on the death of Edith of Wessex

Edith of Wessex ( 1025 – 18 December 1075) was Queen of England from her marriage to Edward the Confessor in 1045 until Edward died in 1066. Unlike most English queens in the 10th and 11th centuries, she was crowned. The principal source on h ...

, widow of Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

. The settlement included one church, three mills

Mills is the plural form of mill, but may also refer to:

As a name

* Mills (surname), a common family name of English or Gaelic origin

* Mills (given name)

*Mills, a fictional British secret agent in a trilogy by writer Manning O'Brine

Places Uni ...

worth 15s 4d, 16 plough

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

s, woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the '' plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

and herbage for 88 hogs and of meadow

A meadow ( ) is an open habitat, or field, vegetated by grasses, herbs, and other non- woody plants. Trees or shrubs may sparsely populate meadows, as long as these areas maintain an open character. Meadows may be naturally occurring or arti ...

. It rendered £18 per year in 1086. The residents included 38 villagers, 14 smallholders and 4 villein

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

s, which placed it in the top 20% of settlements in England by population.lordship

A lordship is a territory held by a lord. It was a landed estate that served as the lowest administrative and judicial unit in rural areas. It originated as a unit under the feudal system during the Middle Ages. In a lordship, the functions of econ ...

almost continuously until the present day.[ By the early 14th century, the manor had been divided for administrative purposes into four ]tithing

A tithing or tything was a historic English legal, administrative or territorial unit, originally ten hides (and hence, one tenth of a hundred). Tithings later came to be seen as subdivisions of a manor or civil parish. The tithing's leader or ...

s: Eastburgh and Chippingburgh (corresponding respectively to the eastern and western halves of the modern town); Foreignburgh (the area covered by the Holmwoods) and Waldburgh (which would later be renamed Capel).[ On the death of the seventh Earl, John de Warenne, in 1347, the manor passed to his ]brother-in-law

A sibling-in-law is the spouse of one's sibling, or the sibling of one's spouse, or the person who is married to the sibling of one's spouse.Cambridge Dictionaries Online.Family: non-blood relations.

More commonly, a sibling-in-law is referre ...

, Richard Fitzalan, the third Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and is used (along with the Earl of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title. The ...

. In 1580 both Earldoms passed through the female line to Phillip Howard, whose father, Thomas Howard, had forfeited the title of Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

and had been executed for his involvement in the Ridolfi plot to assassinate Elizabeth I. As the status of the de Warennes and their descendants increased, they became less interested in the town. In the 14th and 15th centuries, prominent local families (including the Sondes and the Goodwyns) were able to buy the leases on some of the lordship lands.

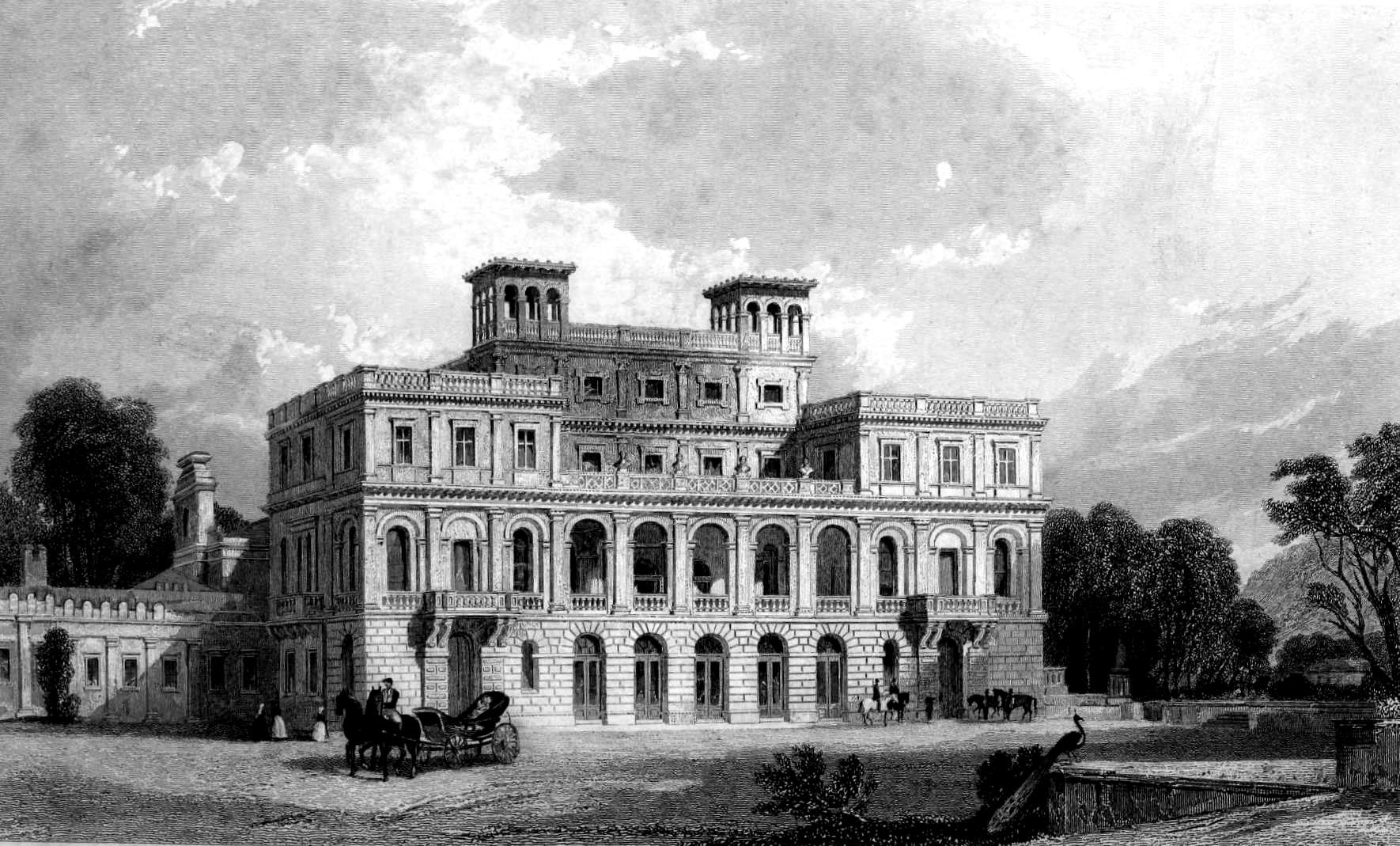

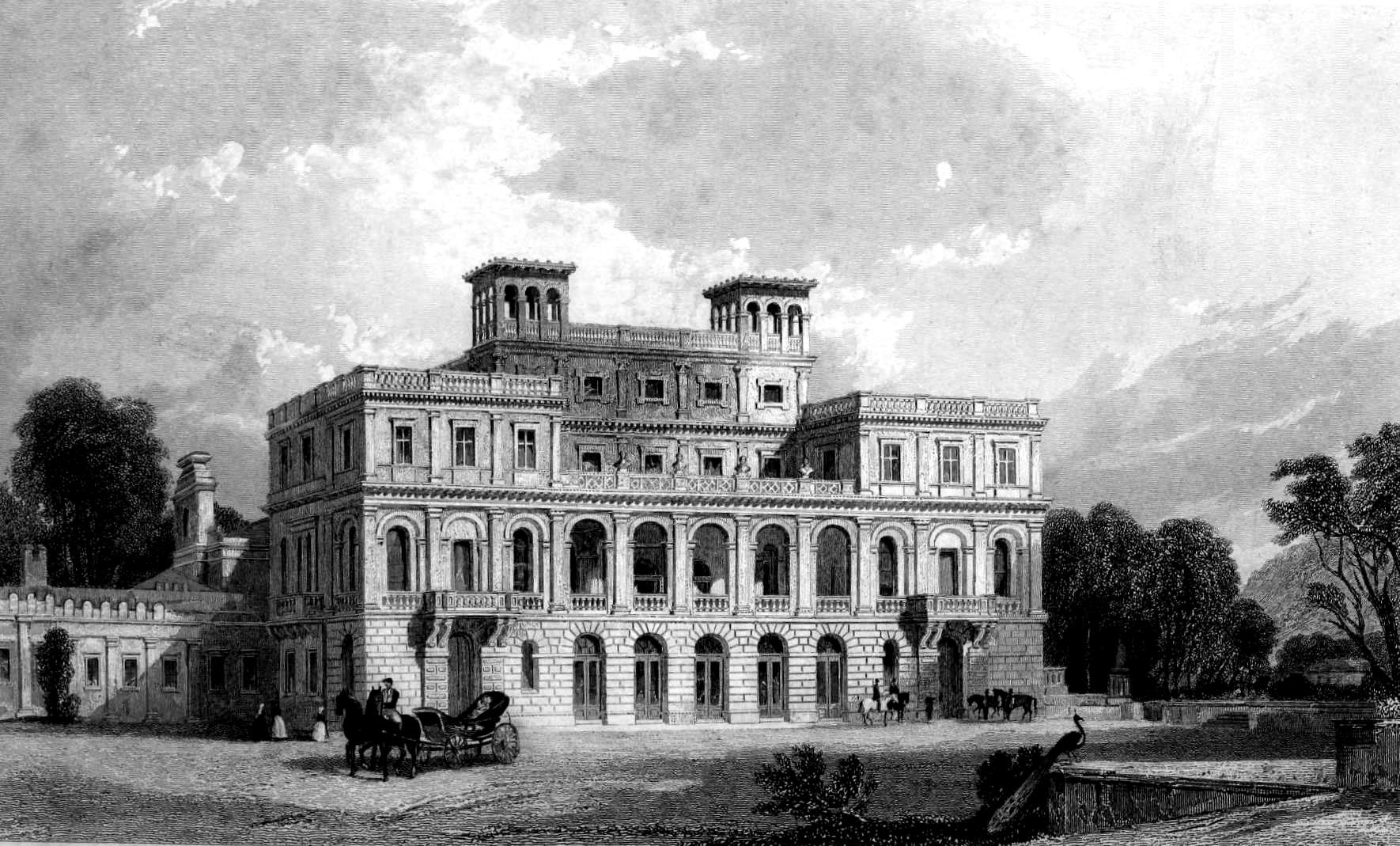

As the status of the de Warennes and their descendants increased, they became less interested in the town. In the 14th and 15th centuries, prominent local families (including the Sondes and the Goodwyns) were able to buy the leases on some of the lordship lands.Henry Thomas Hope

Henry Thomas Hope (30 April 1808 – 4 December 1862) was a British MP and patron of the arts.

Biography

Henry Thomas Hope was born in London on 30 April 1808, the eldest of the three sons of the connoisseur Thomas Hope (1769–1831) and his ...

, who commissioned William Atkinson to remodel the main house as a "sumptuous High Renaissance palazzo".Reigate

Reigate ( ) is a town in Surrey, England, around south of central London. The settlement is recorded in Domesday Book in 1086 as ''Cherchefelle'' and first appears with its modern name in the 1190s. The earliest archaeological evidence for huma ...

, Dorking was never granted a Borough Charter and remained under the control of the Lord of the Manor throughout the Middle Ages.[ Reforms during the Tudor period reduced the importance of ]manorial court

The manorial courts were the lowest courts of law in England during the feudal period. They had a civil jurisdiction limited both in subject matter and geography. They dealt with matters over which the lord of the manor had jurisdiction, primaril ...

s and the day-to-day administration of towns such as Dorking became the responsibility of the vestry

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquiall ...

of the parish church.Poor Law Amendment Act 1834

The ''Poor Law Amendment Act 1834'' (PLAA) known widely as the New Poor Law, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed by the Whig government of Earl Grey. It completely replaced earlier legislation based on the ''Poor Relie ...

transferred responsibility for poor relief to the Poor Law Commission

The Poor Law Commission was a body established to administer poor relief after the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. The commission was made up of three commissioners who became known as "The Bashaws of Somerset House", their secretary a ...

, whose local powers were delegated to the newly formed poor law union in 1836.workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

, south of the town centre, designed by William Shearburn. The entrance block still stands and is now part of Dorking Hospital.

A local board of health

Local boards or local boards of health were local authorities in urban areas of England and Wales from 1848 to 1894. They were formed in response to cholera epidemics and were given powers to control sewers, clean the streets, regulate environmenta ...

(LBH) was established in Dorking in 1881 to administer infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

including roads, street lighting and drainage. The LBH organised the first regular domestic refuse collection

Waste collection is a part of the process of waste management. It is the transfer of solid waste from the point of use and disposal to the point of treatment or landfill. Waste collection also includes the curbside collection of recyclable ...

and, by mid-1888, had created a new sewerage system (including a treatment works at Pixham).Local Government Act 1888

Local may refer to:

Geography and transportation

* Local (train), a train serving local traffic demand

* Local, Missouri, a community in the United States

* Local government, a form of public administration, usually the lowest tier of administrat ...

transferred many administrative responsibilities to the newly formed Surrey County Council

Surrey County Council is the county council administering certain services in the non-metropolitan county of Surrey in England. The council is composed of 81 elected councillors, and in all but one election since 1965 the Conservative Party has ...

and was followed by an 1894 Act that created the Dorking Urban District Council (UDC).[ Initially the offices of the UDC were in South Street,][ but in 1931 the Council moved to Pippbrook House, a ]Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

country house to the north east of the town centre, designed as a private residence by George Gilbert Scott

Sir George Gilbert Scott (13 July 1811 – 27 March 1878), known as Sir Gilbert Scott, was a prolific English Gothic Revival architect, chiefly associated with the design, building and renovation of churches and cathedrals, although he started ...

in 1856.Local Government Act 1972

The Local Government Act 1972 (c. 70) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales on 1 April 1974. It was one of the most significant Acts of Parliament to be passed by the Heath Gov ...

created Mole Valley District Council

Mole Valley is a local government district in Surrey, England. Its council is based in Dorking.

The other town in the district is Leatherhead. The largest villages are Ashtead, Fetcham and Great Bookham, in the northern third of the district. ...

(MVDC), by combining the UDCs of Dorking and Leatherhead with the majority of the Dorking and Horley Rural District. In 1984, the new council moved into purpose-built offices, designed by Michael Innes, at the east end of the town.

Transport and communications

Following the end of Roman rule in Britain

The end of Roman rule in Britain was the transition from Roman Britain to post-Roman Britain. Roman rule ended in different parts of Britain at different times, and under different circumstances.

In 383, the usurper Magnus Maximus withdrew t ...

, there appears to have been no systematic planning of transport infrastructure in the local area for over a millennium

A millennium (plural millennia or millenniums) is a period of one thousand years, sometimes called a kiloannus, kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting ...

. During Saxon times, the section of Stane Street between Dorking and Ockley was bypassed by the longer route via Coldharbour and the upper surface of the Roman road was most likely quarried to provide stone for local building projects.Tadworth

Tadworth is a large suburban village in Surrey, England in the south-east of the Epsom Downs, part of the North Downs. It forms part of the Borough of Reigate and Banstead. At the 2011 census, Tadworth (and Walton-on-the-Hill) had a population o ...

.[

The development of Guildford ( to the west) was stimulated by the construction of the ]Wey Navigation

The River Wey Navigation and Godalming Navigation together provide a continuous navigable route from the River Thames near Weybridge via Guildford to Godalming (commonly called the Wey Navigation). Both waterways are in Surrey and are owned ...

in the 1650s. In contrast, although several schemes were proposed to make the Mole navigable, none were enacted[

The turnpike road through Dorking was authorised by the Horsham and Epsom Turnpike Act of 1755. The new turnpike dramatically improved the accessibility of the town from the capital. A ]mail coach

A mail coach is a stagecoach that is used to deliver mail. In Great Britain, Ireland, and Australia, they were built to a General Post Office-approved design operated by an independent contractor to carry long-distance mail for the Post Office. M ...

operated return journeys between Dorking and London six days per week and several stagecoach

A stagecoach is a four-wheeled public transport coach used to carry paying passengers and light packages on journeys long enough to need a change of horses. It is strongly sprung and generally drawn by four horses although some versions are dra ...

es used the route daily until the mid-19th century.[

] The first railway line to reach Dorking was the Reading, Guildford and Reigate Railway (RG&RR), authorised by Acts of Parliament in 1846, 1847 and 1849.

The first railway line to reach Dorking was the Reading, Guildford and Reigate Railway (RG&RR), authorised by Acts of Parliament in 1846, 1847 and 1849.London, Brighton and South Coast Railway

The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR; known also as the Brighton line, the Brighton Railway or the Brighton) was a railway company in the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1922. Its territory formed a rough triangle, with London at its ...

in 1867.[

was provided with extensive goods facilities, a locomotive yard and a turntable (later the site of the car park).][ It was built with two platforms, but a third was added in 1925, when the railway line was ]electrified

Electrification is the process of powering by electricity and, in many contexts, the introduction of such power by changing over from an earlier power source.

The broad meaning of the term, such as in the history of technology, economic history ...

from .Biwater

Biwater International Limited provides large-scale water and wastewater treatment solutions. It has completed over 25,000 projects in over 90 countries.

Adrian White, CBE, founded Biwater in 1968, and is the Executive Chairman. White is also the ...

.bypass road

A bypass is a road or highway that avoids or "bypasses" a built-up area, town, or village, to let through traffic flow

In mathematics and transportation engineering, traffic flow is the study of interactions between travellers (including p ...

(now the A24) was opened in 1934 following considerable local opposition to the route, which cut through the Deepdene estate.

Commerce and industry

A market at Dorking is first recorded in 1240 and in 1278, the sixth Earl of Surrey, John de Warenne, claimed that it had been held twice weekly since " time out of mind". The early medieval market was probably centred around Pump Corner and between South Street and West Street, but it appears to have moved east to the widest part of the High Street by the early 15th century.[

In the century following the Norman conquest, agricultural activity was focused on the lordship lands, which lay to the north of the Pipp Brook. However, as the Middle Ages progressed, woodland to the south and west of the centre was cleared enabling farms owned by the Goodwyns, Stubbs and Sondes families to expand.][ By the start of the Tudor period, there were at least five watermills in Dorking – two at Pixham (one on the Pipp Brook, owned by the Sondes and one on the Mole, owned by the Brownes), two close to the town centre (both owned by the manor) and one at Milton, on the road to Westcott. There may also have been a windmill on Tower Hill.][

] The town flourished in Tudor times and, in the 1590s, a market house was built between what is now St Martin's Walk and the White Horse Hotel.

The town flourished in Tudor times and, in the 1590s, a market house was built between what is now St Martin's Walk and the White Horse Hotel.[ The ]antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

John Aubrey

John Aubrey (12 March 1626 – 7 June 1697) was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the '' Brief Lives'', his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist ...

, who visited the town between 1673 and 1692, noted that the weekly market (which took place on Thursdays) was "the greatest... for poultry in England" and noted that "Sussex wheat" was also sold.digestive systems

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans an ...

. The Dorking fowl, which has five claws instead of the normal four, is named after the town.Wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from Fermentation in winemaking, fermented grapes. Yeast in winemaking, Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different ...

made from the wild cherries

The Wild Cherries were an Australian rock group, which started in late 1964 playing R&B/jazz and became "the most relentlessly experimental psychedelic band on the Melbourne discotheque / dance scene" according to commentator, Glenn A. Baker ...

that grew in the town was another local speciality. A 'cherry fair' was held in July in the 17th and 18th centuries,Ascension Day

The Solemnity of the Ascension of Jesus Christ, also called Ascension Day, Ascension Thursday, or sometimes Holy Thursday, commemorates the Christian belief of the bodily Ascension of Jesus into heaven. It is one of the ecumenical (i.e., shared b ...

.[

Chalk and sand were quarried in Dorking until the early 20th century. Chalk was dug from a pit on Ranmore Road and heated in ]kilns

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay int ...

to produce quicklime

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term "'' lime''" connotes calcium-containing inorganic m ...

. In the medieval and early modern periods, the lime was used to fertilise

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Proce ...

local farm fields, but from the 18th century onwards (and especially after the construction of the turnpike to Epsom in 1755), it was transported to London for use in the construction industry.seams

Seam may refer to:

Science and technology

* Seam (geology), a stratum of coal or mineral that is economically viable; a bed or a distinct layer of vein of rock in other layers of rock

* Seam (metallurgy), a metalworking process the joins the end ...

of silver sand Silver sand is a fine white sand used in gardening. It consists largely of quartz particles that are not coated with iron oxides. Iron oxides colour sand from yellows to rich brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it ...

, which was used in glass making

Glass production involves two main methods – the float glass process that produces sheet glass, and glassblowing that produces bottles and other containers. It has been done in a variety of ways during the history of glass.

Glass container ...

.cockpit

A cockpit or flight deck is the area, usually near the front of an aircraft or spacecraft, from which a pilot controls the aircraft.

The cockpit of an aircraft contains flight instruments on an instrument panel, and the controls that e ...

beneath the former Wheatsheaf Inn in the High Street, in which fighting cocks were set against each other for sport

Sport pertains to any form of competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to spectators. Sports can, ...

. During the construction of the car park

A parking lot (American English) or car park (British English), also known as a car lot, is a cleared area intended for parking vehicles. The term usually refers to an area dedicated only for parking, with a durable or semi-durable surface ...

to the south of Sainsbury's supermarket, the builders broke through into a large cavern of unknown date, the walls of which were painted with ''trompe-l'œil

''Trompe-l'œil'' ( , ; ) is an artistic term for the highly realistic optical illusion of three-dimensional space and objects on a two-dimensional surface. ''Trompe l'oeil'', which is most often associated with painting, tricks the viewer into ...

'' pillars. Unfortunately, in order to complete the car park, it was necessary to fill in the cave with concrete.[ Guided tours of the caves in South Street are held on a regular basis and are organised by Dorking Museum.]mechanisation of agriculture

Mechanised agriculture or agricultural mechanization is the use of machinery and equipment, ranging from simple and basic hand tools to more sophisticated, motorized equipment and machinery, to perform agricultural operations. In modern times, po ...

was leading to a local surplus of labour. The wages for unskilled farm workers were decreasing, exacerbated by a fall in produce prices following the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

in 1815. Like many towns in the south of England, Dorking was affected by civil unrest

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, or social unrest is a situation arising from a mass act of civil disobedience (such as a demonstration, riot, strike, or unlawful assembly) in which law enforcement has difficulty ...

among its poorest residents.Life Guards regiment

The 1st Regiment of Life Guards was a cavalry regiment in the British Army, part of the Household Cavalry. It was formed in 1788 by the union of the 1st Troop of Horse Guards and 1st Troop of Horse Grenadier Guards. In 1922, it was amalgamated wi ...

was called in to restore order. In 1831 it was noted that the town (population 4711) had one of the highest rates of poor relief in Surrey.[

In early 1832, the ]vestry

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquiall ...

devised a supported scheme to enable young unemployed, unskilled labourers to leave the town to settle

Settle or SETTLE may refer to:

Places

* Settle, Kentucky, United States

* Settle, North Yorkshire, a town in England

** Settle Rural District, a historical administrative district

Music

* Settle (band), an indie rock band from Pennsylvania

* ''S ...

in Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North Americ ...

. The cost of the voyage from Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

for 61 recipients of poor relief was paid by private donations, however the emigrants also received an allowance for food and clothing from parish funds. Although many were young, single men aged 14–20, a few families also joined the group. Most appear to have settled in the Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

area, but a few are recorded as living in Kingston, Ontario

Kingston is a city in Ontario, Canada. It is located on the north-eastern end of Lake Ontario, at the beginning of the St. Lawrence River and at the mouth of the Cataraqui River (south end of the Rideau Canal). The city is midway between Tor ...

.[

In 1911, the town was described in the ]Victoria County History

The Victoria History of the Counties of England, commonly known as the Victoria County History or the VCH, is an English history project which began in 1899 with the aim of creating an encyclopaedic history of each of the historic counties of E ...

as "almost entirely residential and agricultural, with some lime works on the chalk, though not so extensive as those in neighbouring parishes, a little brick-making, watermills (corn) at Pixham Mill, and timber and saw-mills."[

]

Residential development

Although the turnpike road through Dorking had been constructed in the 1750s,[ the built-up part of the town had changed little by the start of the 19th century.]sanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation syste ...

was still a major problem for the poorer residents and, in 1832, a cholera outbreak

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817. The seventh cholera pandemic is officially a current pandemic and has been ongoing since 1961, according to a World Health Organiza ...

was recorded in Ebenezer Place (north of the High Street), where 46 people were crammed into nine cottages.[

Nevertheless, Dorking was beginning to attract more affluent residents, many of whom had accumulated their wealth as businessmen in London. Charles Barclay (a ]Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

brewery owner) and the bankers Joseph Denison and Thomas Hope (none of whom had any previous connection with the area) purchased the estates at Bury Hill, Denbies and Deepdene respectively. Higher-status individuals living closer to the town centre included William Crawford William Crawford may refer to:

Entertainment

* William Broderick Crawford (1911–1986), American film actor

* Bill Crawford (cartoonist) (1913–1982), American editorial cartoonist

* William L. Crawford (1911–1984), U.S. publisher and editor

...

, the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

MP, and Jane Leslie, the Dowager Countess of Rothes.[ Although the incoming landowners played little part in local commerce, they appear to have been the driving force behind schemes to pave streets and to provide ]gas lighting

Gas lighting is the production of artificial light from combustion of a gaseous fuel, such as hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide, propane, butane, acetylene, ethylene, coal gas (town gas) or natural gas. The light is produced either directly ...

(both paid for by public subscription

Subscription refers to the process of investors signing up and committing to invest in a financial instrument, before the actual closing of the purchase. The term comes from the Latin word ''subscribere''.

Historical Praenumeration

An early form ...

). Rose Hill, the first planned residential estate in Dorking, was developed by William Newland, a wealthy Guildford surgeon, who also had interests in the Wey and Arun Canal. Newland purchased the "Great House" on Butter Hill and the surrounding of land in 1831, which he divided into plots for 24 houses, arranged around a central

Rose Hill, the first planned residential estate in Dorking, was developed by William Newland, a wealthy Guildford surgeon, who also had interests in the Wey and Arun Canal. Newland purchased the "Great House" on Butter Hill and the surrounding of land in 1831, which he divided into plots for 24 houses, arranged around a central paddock

A paddock is a small enclosure for horses. In the United Kingdom, this term also applies to a field for a general automobile racing competition, particularly Formula 1.

Description

In Canada and the United States of America, a paddock is a small ...

, known as "The Oval". The Great House was divided into two separate dwellings (Butter Hill House and Rose Hill House), adjacent to which a mock-Tudor arch was erected over the main carriageway entrance from South Street. Initially sales were slow, but the proposals for the building of the railway line from Redhill stimulated interest in the development in the late 1840s. Although most of the purchasers were private individuals (the majority of whom had been born outside of the local area), the Dorking Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

bought one of the plots in 1845 for the construction of a meeting house

A meeting house (meetinghouse, meeting-house) is a building where religious and sometimes public meetings take place.

Terminology

Nonconformist Protestant denominations distinguish between a

* church, which is a body of people who believe in Ch ...

.[

The arrival of the railway in 1849 catalysed the expansion of the town to the south and west. Between 1850 and 1870, the National Freehold Land Society was responsible for housing developments in Arundel and Howard Roads, as well as around Tower Hill. Poorer quality houses were built along Falkland and Hampstead Roads (many of which were replaced in the 1960s and 1970s). Holloway Farm was sold in 1870 and the first houses in Knoll, Roman and Ridgeway Roads were constructed before 1880. Houses in Cliftonville (named after its promoter, Joseph Clift, a local ]chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

) were also built around the same time.semi-detached

A semi-detached house (often abbreviated to semi) is a single family duplex dwelling house that shares one common wall with the next house. The name distinguishes this style of house from detached houses, with no shared walls, and terraced hous ...

and terraced house

In architecture and city planning, a terrace or terraced house ( UK) or townhouse ( US) is a form of medium-density housing that originated in Europe in the 16th century, whereby a row of attached dwellings share side walls. In the United St ...

s were constructed in the 1890s for artisans in Rothes Road, Ansell Road, Wathen Road, Hart Road and Jubilee Terrace.[

No significant residential expansion took place in Dorking in the first two decades of the 20th century. In the 1920s and 1930s, the breakup of the Deepdene and Pippbrook estates (and the electrification of the railway line from Leatherhead) stimulated housebuilding to the north and east of the town, including Deepdene Vale and Deepdene Park.]Denbies Wine Estate

Denbies Wine Estate, near Dorking, Surrey, has the largest vineyard in England, with under vines, representing more than 10 per cent of the plantings in the whole of the United Kingdom. It has a visitors' centre that attracts around 300,000 visit ...

), however their plans were interrupted by the outbreak of war and were ultimately prevented by the creation of the Metropolitan Green Belt

The Metropolitan Green Belt is a statutory green belt around London, England. It comprises parts of Greater London, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent and Surrey, parts of two of the three districts of Bedfordshire and a s ...

.[

] The first

The first council housing

Public housing in the United Kingdom, also known as council estates, council housing, or social housing, provided the majority of rented accommodation until 2011 when the number of households in private rental housing surpassed the number in so ...

was built in Dorking by the UDC in Nower Road in 1920 and similar developments took place in Marlborough and Beresford Roads later the same decade. In 1936, the council obtained a Slum Clearance Order to demolish 81 properties in Church Street, North Street, Cotmandene and the surrounding areas. In total 217 residents were displaced, many of whom were rehoused by the UDC in the Fraser Gardens estate, designed by the architect George Grey Wornum. The Chart Downs estate to the southeast of the town was built between 1948 and 1952.[

Controversially, in the late 1950s and 1960s, Dorking UDC constructed the ]Goodwyns

Goodwyns is a housing estate in Dorking, a market town in Surrey, England. It is on the return slope of one of two hillsides of the town and adjoins North Holmwood, a green-buffered village. The town centre is about away.

History and architec ...

estate on land compulsorily purchased from Howard Martineau, a major local benefactor to the town. The initial designs were by Clifford Culpin and the project was subsequently developed by William Ryder, who was responsible for the erection of the Wenlock Edge and Linden Lea tower blocks

A tower block, high-rise, apartment tower, residential tower, apartment block, block of flats, or office tower is a tall building, as opposed to a low-rise building and is defined differently in terms of height depending on the jurisdicti ...

.[ Both the design of the buildings and the layout of the estate were praised in the early 1970s by architectural historians ]Ian Nairn

Ian Douglas Nairn (24 August 1930 – 14 August 1983) was a British architectural critic who coined the word "Subtopia" to indicate drab suburbs that look identical through unimaginative town-planning. He published two strongly personalised criti ...

and Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, '' The Buildings of England'' ...

.

Religion

The first mention of a church at Dorking occurs in Domesday Book of 1086.[ In around 1140, Isabel de Warenne, the widow of the second Earl of Surrey, granted the church and a ]tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

of the rents from the manor to Lewes Priory

Lewes Priory is a part-demolished medieval Cluniac priory in Lewes, East Sussex in the United Kingdom. The ruins have been designated a Grade I listed building.

History

The Priory of St Pancras was the first Cluniac house in England and ha ...

in Sussex. In the 1190s, the tithe was converted to a pension of £6, which was paid annually to the Priory until at least 1291. It is unclear where in the town the Domesday church was located. It appears to have been replaced at some point during the 12th century (possibly by Isabel de Warenne) by a large cruciform building with a central tower.

It is unclear where in the town the Domesday church was located. It appears to have been replaced at some point during the 12th century (possibly by Isabel de Warenne) by a large cruciform building with a central tower.[ A rededication from ]St Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

to St Martin may have taken place around the same time.[ In 1334 the church was granted to the Priory of the Holy Cross in Reigate.]clerestory

In architecture, a clerestory ( ; , also clearstory, clearstorey, or overstorey) is a high section of wall that contains windows above eye level. Its purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both.

Historically, ''clerestory'' denoted an upper l ...

and two side aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, pa ...

s were added to the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

.[ It had a square tower, topped with an octagonal ]spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires a ...

, and could seat around 1800 worshippers.crypt

A crypt (from Latin '' crypta'' " vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, sarcophagi, or religious relics.

Originally, crypts were typically found below the main apse of a c ...

. In 1868–1877, the Intermediate Church was rebuilt into the present St Martin's Church, designed in the Decorated Gothic style by the architect Henry Woodyer.Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public speakers of his day. Natural ...

(who had died in 1873)Lady chapel

A Lady chapel or lady chapel is a traditional British term for a chapel dedicated to "Our Lady", Mary, mother of Jesus, particularly those inside a cathedral or other large church. The chapels are also known as a Mary chapel or a Marian chapel, ...

was added.[

In order to accommodate the growing population in the south of the town, a second ]Anglican church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

, St Paul's, was opened in 1857 on land donated by Henry Thomas Hope. Designed by the architect, Benjamin Ferrey

Benjamin Ferrey FSA FRIBA (1 April 1810–22 August 1880) was an English architect who worked mostly in the Gothic Revival.

Family

Benjamin Ferrey was the youngest son of Benjamin Ferrey Snr (1779–1847), a draper who became Mayor of Christc ...

, it was built of Bath stone

Bath Stone is an oolitic limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate. Originally obtained from the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines under Combe Down, Somerset, England. Its honey colouring gives the World Heritage City of ...

in the Decorated Geometric style.Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens ( ; 29 March 1869 – 1 January 1944) was an English architect known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era. He designed many English country houses, war memor ...

and dedicated to St Mary, was opened at Pixham in 1903.protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and by 1676, the parish (which had a total population of around 1500) contained 200 nonconformists.Priscilla

Priscilla is an English female given name adopted from Latin ''Prisca'', derived from ''priscus''. One suggestion is that it is intended to bestow long life on the bearer.

The name first appears in the New Testament of Christianity variously as ...

, joined the ''Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, ...

'' to establish a Separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

colony in the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

.Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, the townsfolk supported the Parliamentarians, but although some of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

's soldiers were billet

A billet is a living-quarters to which a soldier is assigned to sleep. Historically, a billet was a private dwelling that was required to accept the soldier.

Soldiers are generally billeted in barracks or garrisons when not on combat duty, alth ...

ed in Dorking, no fighting took place nearby.Christopher Feake

Christopher Feake (1612–1683) was an English Independent minister and Fifth-monarchy man. He was imprisoned for maligning Oliver Cromwell in his preaching. He is a leading example of someone sharing both Leveller views and the millenarian approa ...

, the Fifth Monarchist and independent minister, lived in the town (allegedly under a false identity) following The Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. He may have incited some of the more radical residents to violence.Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel '' Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

, the author of ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tra ...

'' and a committed Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

throughout his life, was educated in Dorking for five years, . He attended a school in Pixham Lane run by Revd James Fisher a non-conformist who had been ejected as Rector of Fetcham

Fetcham is a suburban village in Surrey, England west of the town of Leatherhead, on the other side of the River Mole and has a mill pond, springs and an associated nature reserve. The housing, as with adjacent Great Bookham, sits on the lower ...

.[ In 1662 Fisher was involved in establishing Dorking Congregational Church, which by the 1690s was meeting in a barn on Butter Hill in South Street. The present United Reformed Church in West Street, designed by the architect William Hopperton, was built for the group by William Shearburn in 1834.

]John Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, theologian, and evangelist who was a leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies he founded became the dominant form of the independent Meth ...

visited Dorking a total of nineteen times between 1764 and 1789.Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

chapel in the town in 1777. A new church with a spire was built in South Street in 1900, however this building was sold and demolished in 1974. Since 1973, Dorking Methodists have held services

Service may refer to:

Activities

* Administrative service, a required part of the workload of university faculty

* Civil service, the body of employees of a government

* Community service, volunteer service for the benefit of a community or a p ...

at St Martin's.Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

country during the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, the families of the Earls of Arundel and Dukes of Norfolk remained Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...