Donegall Street bombing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Donegall Street bombing took place in

At 11.58 a.m. a

At 11.58 a.m. a

Retrieved 8 January 2012 The remains of the two policemen, who had been blown to pieces, were alleged to have been found inside a nearby building. Minutes earlier they had been helping to escort people away from Church Street."Bomb-torn Ulster awaits peace plan". ''The Sydney Morning Herald''. 22 March 1972. p.1. Retrieved 9 January 2012 The explosion sent a ball of flame rolling down the street and a pall of black smoke rose upwards."Bomb kills six persons in Belfast". 'The Spartanburg Herald''. 21 March 1972''. p.1. Retrieved 9 January 2012 The blast wave ripped into the crowds of people who had run into Donegall Street for safety, tossing them in all directions and killing another four men outright: three of them, Ernest Dougan (39), James Macklin (30) and Samuel Trainor (39) were corporation binmen working in the area, and the fourth man was Sydney Bell (65). Trainor was also an off-duty

/ref> The explosion blew out all the windows in the vicinity, sending shards of glass into people's bodies as they were hit by falling masonry and timber; severed limbs were hurled into the road and into the mangled front of an office building. The ground floor of the ''News Letter'' offices and all buildings in the area suffered heavy damage. The ''News Letter'' library in particular sustained considerable damage with many priceless photographs and old documents destroyed."Workers recall horror of blast, 40 years on". ''Belfast News Letter''. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012 Around the blast's epicentre, the street resembled a battlefield. About one hundred schoolgirls lay wounded on the rubble-strewn, bloody pavement covered in glass and debris, and screaming in pain and fright. A total of 148 people were injured in the explosion, 19 of them seriously,Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p.98 including people who had lost eyes and were badly maimed."Six die in Ulster terrorist blast". ''Montreal Gazette''. 20 March 1972. p.47. Retrieved 9 January 2012 Among the injured were many ''News Letter'' staff. One of the wounded was a child whose injuries were so severe a rescue worker at the scene assumed the child had been killed. A young Czech art student Blanka Sochor (22) received severe injuries to her legs; she was photographed by Derek Brind of the ''

Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

on 20 March 1972 when, just before noon, the Provisional IRA

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, fa ...

detonated a car bomb

A car bomb, bus bomb, lorry bomb, or truck bomb, also known as a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED), is an improvised explosive device designed to be detonated in an automobile or other vehicles.

Car bombs can be roughly divided ...

in Lower Donegall Street in the city centre

A city centre is the commercial, cultural and often the historical, political, and geographic heart of a city. The term "city centre" is primarily used in British English, and closely equivalent terms exist in other languages, such as "" in Fren ...

when the street was crowded with shoppers, office workers, and many schoolchildren.

Seven people were killed in the explosion, including two members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

(RUC), who said they had evacuated people to what was considered to have been a safe area following misleading telephone calls, which had originally placed the device in a nearby street. The Provisional IRA Belfast Brigade

The Belfast Brigade of the Provisional IRA was the largest of the organisation's brigades, based in the city of Belfast, Northern Ireland.

The nucleus of the Belfast Brigade emerged in the divisions within Belfast republicans in the closing month ...

admitted responsibility for the bomb, which also injured 148 people, but claimed that the security forces had deliberately misrepresented the warnings in order to maximise the casualties. This was one of the first car bombs the IRA used in their armed campaign.

The bombing

Warning telephone calls

On Monday 20 March 1972, at 11.45 a.m., a local carpet dealer received a telephone call warning that a bomb would explode in Belfast city centre's Church Street which was crowded with shoppers, office workers on lunch breaks, and schoolchildren.British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

troops and the RUC were alerted and immediately began to evacuate the people into nearby Lower Donegall Street. The second call to the ''Irish News'' newspaper seven minutes later also gave Church Street as the location for the device. When a final call came at 11.55 advising the ''News Letter

The ''News Letter'' is one of Northern Ireland's main daily newspapers, published from Monday to Saturday. It is the world's oldest English-language general daily newspaper still in publication, having first been printed in 1737.

The newspape ...

'' newspaper that the bomb was instead placed outside its offices in Lower Donegall Street where the crowds were being sent. Thus, the warning arrived too late for the security forces to clear the street. Staff working inside the ''News Letter'' were told by the caller that they had 15 minutes in which to leave the building, but they never had a chance to evacuate.

The explosion

gelignite

Gelignite (), also known as blasting gelatin or simply "jelly", is an explosive material consisting of collodion-cotton (a type of nitrocellulose or guncotton) dissolved in either nitroglycerine or nitroglycol and mixed with wood pulp and saltpe ...

bomb exploded inside a green Ford Cortina

The Ford Cortina is a medium-sized family car that was built initially by Ford of Britain, and then Ford of Europe in various guises from 1962 to 1982, and was the United Kingdom's best-selling car of the 1970s.

The Cortina was produced in fi ...

parked in the street outside the offices of the ''News Letter'', shaking the city centre with the force of its blast, and instantly killing the two RUC constables, Ernest McAllister (31) and Bernard O'Neill (36), who had been examining the vehicle.Police Service of Northern Ireland: Freedom of Information Request: The Murder of Constable Ernest McAllister and Others - 20 March 1972Retrieved 8 January 2012 The remains of the two policemen, who had been blown to pieces, were alleged to have been found inside a nearby building. Minutes earlier they had been helping to escort people away from Church Street."Bomb-torn Ulster awaits peace plan". ''The Sydney Morning Herald''. 22 March 1972. p.1. Retrieved 9 January 2012 The explosion sent a ball of flame rolling down the street and a pall of black smoke rose upwards."Bomb kills six persons in Belfast". 'The Spartanburg Herald''. 21 March 1972''. p.1. Retrieved 9 January 2012 The blast wave ripped into the crowds of people who had run into Donegall Street for safety, tossing them in all directions and killing another four men outright: three of them, Ernest Dougan (39), James Macklin (30) and Samuel Trainor (39) were corporation binmen working in the area, and the fourth man was Sydney Bell (65). Trainor was also an off-duty

Ulster Defence Regiment

The Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) was an infantry regiment of the British Army established in 1970, with a comparatively short existence ending in 1992. Raised through public appeal, newspaper and television advertisements,Potter p25 their offi ...

(UDR) soldier and a member of the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

. A seriously wounded pensioner, Henry Miller (79) would die in hospital on 5 April. Most of the dead were mutilated beyond recognition;Eire-Ireland: a journal of Irish studies, Volume 7. Irish American Cultural Institute. p.43 one of the binmen lay in the road with his head shattered."Scores Killed, Wounded in Belfast Newspaper Blast". ''Lebanon Daily News''. 20 March 1972. p.10. Retrieved 11 January 2012 With the exception of Constable O'Neill, who was a Catholic, the other six victims were Protestants.CAIN: Sutton Index of Deaths - 1972/ref> The explosion blew out all the windows in the vicinity, sending shards of glass into people's bodies as they were hit by falling masonry and timber; severed limbs were hurled into the road and into the mangled front of an office building. The ground floor of the ''News Letter'' offices and all buildings in the area suffered heavy damage. The ''News Letter'' library in particular sustained considerable damage with many priceless photographs and old documents destroyed."Workers recall horror of blast, 40 years on". ''Belfast News Letter''. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012 Around the blast's epicentre, the street resembled a battlefield. About one hundred schoolgirls lay wounded on the rubble-strewn, bloody pavement covered in glass and debris, and screaming in pain and fright. A total of 148 people were injured in the explosion, 19 of them seriously,Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p.98 including people who had lost eyes and were badly maimed."Six die in Ulster terrorist blast". ''Montreal Gazette''. 20 March 1972. p.47. Retrieved 9 January 2012 Among the injured were many ''News Letter'' staff. One of the wounded was a child whose injuries were so severe a rescue worker at the scene assumed the child had been killed. A young Czech art student Blanka Sochor (22) received severe injuries to her legs; she was photographed by Derek Brind of the ''

Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

'' as a British Paratrooper held her in his arms.Geraghty, Tony (1998). ''The Irish War: the hidden conflict between the IRA and British Intelligence''. London: HarperCollins Publishers. p.66 Passerby Frank Heagan witnessed the explosion and came upon what was left of two binmen who had been "blown to pieces". He added that "there was blood everywhere and people moaning and screaming. The street was full of girls and women all wandering around". The injured could be heard screaming as the ambulances transported them to hospital; emergency amputations were performed at the scene. One policeman angrily denounced the attack by stating: "This was a deliberate attempt to kill innocent people. The people who planted it must have known that people were being evacuated into its path".

Whilst the security forces and firemen pulled victims from the debris in Donegall Street, two more bombs went off elsewhere in the city centre; however, nobody was hurt in either attack. That same day in Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

, a British soldier, John Taylor, was shot dead by an IRA sniper. In Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, the IRA's Chief of Staff, Seán Mac Stíofáin

Seán Mac Stíofáin (born John Edward Drayton Stephenson; 17 February 1928 – 18 May 2001) was an English-born chief of staff of the Provisional IRA, a position he held between 1969 and 1972.

Childhood

Although he used the Gaelicised ver ...

, suffered burns to his face and hands after he opened a letter bomb sent to him through the post. Cathal Goulding

Cathal Goulding ( ga, Cathal Ó Goillín; 2 January 1923 – 26 December 1998) was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army and the Official IRA.

Early life and career

One of seven children born on East Arran Street in north Dublin to an ...

, head of the Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA (OIRA; ) was an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and create a "workers' republic" encompassing all of Ireland. It emerged ...

, also received a letter bomb but escaped injury by having dismantled the device before it exploded."Victims may have been lured by phone calls". ''The Glasgow Herald''. 21 March 1972. p.1. Retrieved 12 January 2012

This was amongst the first carbombs that the Provisional IRA used during The Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

in its militant campaign to force a British military withdrawal and reunite the six counties of Northern Ireland with the rest of the island of Ireland.Taylor, Peter (1998). ''Provos: The IRA and Sinn Féin''. p.134 It was part of the IRA's escalation of violence to avenge the Bloody Sunday killings in which 13 unarmed Catholic civilian men were killed by the British Army's Parachute Regiment when the latter opened fire during an anti-internment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

demonstration held in Derry on 30 January 1972.Taylor. ''Loyalists''. p.94

Aftermath

The bombing was carried out by the North Belfast unit of the Provisional IRA's Third BattalionBelfast Brigade

"Belfast Brigade" is an Irish folk song, to the tune of "Battle Hymn of the Republic".

Context

The song is about the Belfast Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and in particular the 1st, or West Belfast battalion, during the Irish War ...

. The OC of the Brigade at that time was the volatile Seamus Twomey

Seamus Twomey ( ga, Séamus Ó Tuama; 5 November 1919 – 12 September 1989) was an Irish republican activist, militant, and twice chief of staff of the Provisional IRA.

Biography

Born in Belfast on Marchioness Street,Volunteer Seamus Twomey, 19 ...

, who had ordered and directed the attack.

On 23 March, the IRA admitted responsibility for the bomb with one Belfast Brigade officer later telling a journalist "I feel very bad when the innocent die".''Life Magazine''. 7 April 1972. p.37 The IRA, however, tempered the admission by claiming that the caller had given Donegall Street as the correct location for the bomb in all the telephone calls and that the security forces had deliberately evacuated the crowds from Church Street to maximise the casualties.Coogan, Tim Pat (2002). ''The IRA''. pp.381-384 The IRA's official statement claiming responsibility for the blast was released through the Irish Republican Publicity Bureau. It read as follows:

Proper and adequate warnings have been given before all our operations. This practice will continue. Several warnings have been changed by the British security forces in order to cause maximum civilian casualties. "This was the principal factor for the tragic loss of life and heavy civilian casualties in Donegall Street on Monday last".''The Troubles: A Chronology of the Northern Ireland Conflict''. magazine. Glenravel Publications. #Issue 11. March 1972. p.47Tim Pat Coogan suggested that the IRA had overestimated the security forces' capacity to deal with multiple bomb scares, adding that in all probability, the caller had been young, nervous, and inexperienced. It was also alleged that the bombers had intended to leave the carbomb in Church Street but were unable to find a parking place and instead left it in Donegall Street.Shannon, Elizabeth. ''I am of Ireland: women of the North speak out''. Massachusetts University Press. p.60 The attack was condemned by church leaders of all denominations in Ireland. The Official IRA issued a statement disassociating itself from the bombing which it "condemned in the strongest possible terms". Two days prior to the bombing, Bill Craig, former

Retrieved 9 February 2012

Minister of Home Affairs

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

and founder and leader of the Unionist Vanguard movement, had held a rally at Belfast's Ormeau Park

Ormeau Park is the oldest municipal park in Belfast, Northern Ireland, having been officially opened to the public in 1871. It is owned and run by Belfast City Council and is one of the largest and busiest parks in the city and contains a variet ...

attended by 100,000 loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

. There he had made the following speech that struck fear in many people from the Catholic community: "We lster Vanguardmust build up a dossier of the men and women who are a menace to this country. Because if and when the politicians fail us, it may be our job to liquidate the enemy".Taylor. ''Loyalists''. pp.95-97 The next day, 30,000 Catholics paraded through Belfast to Ormeau Park where they held their own rally in protest at Craig's threatening speech. Republican Labour Party

The Republican Labour Party (RLP) was a political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1964, with two MPs at Stormont, Harry Diamond and Gerry Fitt. They had previously been the sole Northern Ireland representatives of the Socialist R ...

leader Paddy Kennedy promised that any Protestant backlash against Catholics "would be met by a counter-backlash by the Irish people".

According to Ed Moloney

Edmund "Ed" Moloney (born 1948–9) is an Irish journalist and author best known for his coverage of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and the activities of the Provisional IRA, in particular.

He worked for the ''Hibernia'' magazine and ''Magill ...

, the bombing was considered a disaster for the IRA. Coming so soon after the horrific Abercorn Restaurant bombing

The Abercorn Restaurant bombing was a bomb attack that took place in a crowded city centre restaurant and bar in Belfast, Northern Ireland on 4 March 1972. The bomb explosion claimed the lives of two young women and injured over 130 people. Man ...

which had killed two young Catholic women and maimed many others, the Donegall Street bombing caused them to lose considerable support from the Catholic and Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

community who recoiled from the carnage the bombing had wrought.Moloney, Ed (2010). ''Voices From the Grave: two men's war in Ireland''. Faber & Faber Limited. pp.102-103

The IRA followed the Donegall Street attack two days later with a carbomb at a carpark adjacent to Great Victoria Street railway station

Great Victoria Street is a railway station serving the city centre of Belfast, Northern Ireland. It is one of two major stations in the city, along with , and is one of the four stations located in the city centre, the others being Lanyon Place ...

and close to the Europa Hotel. Seventy people were treated in hospital for injuries received mainly by flying glass, but there were no deaths. The blast caused considerable damage to two trains, parked vehicles, the hotel, and other buildings in the area."70 injured in explosion near Belfast hotel". ''The Glasgow Herald''. 23 March 1972. p.1. Retrieved 9 January 2012

Political and security aftermath

On 24 March, to the profound shock and anger of loyalists and Unionists, British Prime MinisterEdward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 191617 July 2005), often known as Ted Heath, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conserv ...

announced the suspension of the 50-year-old Stormont parliament

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

and the imposition of Direct Rule from London.

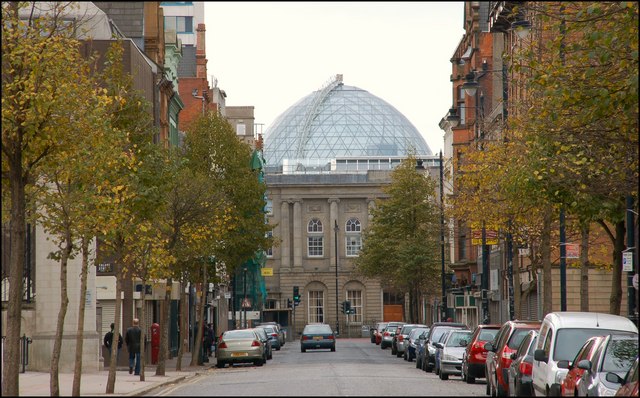

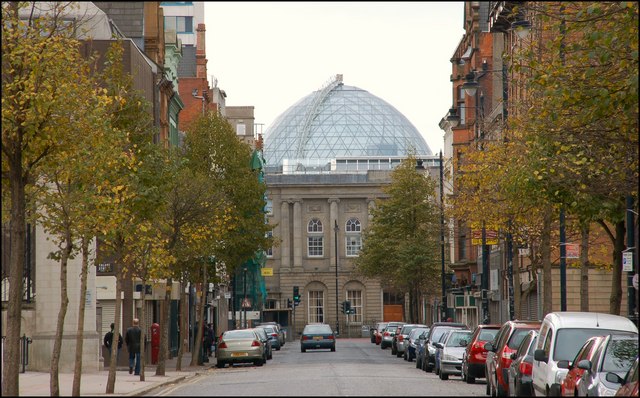

The Donegall Street bombing led to the closure of traffic in the Royal Avenue

Royal Avenue is a street in Belfast, Northern Ireland. In the Cathedral Quarter in the heart of Belfast city centre, as well as being identified with the more recent Smithfield and Union Quarter, it has been the city's principal shopping thor ...

shopping district and the erection of security gates which put a "ring of steel" around Belfast city centre.

Although many members of the Provisional IRA were rounded up by police in the wake of the attack, none of the bombers were ever caught nor was anybody ever charged in connection with the bombing.

In her 1973 book ''To Take Arms: My Life With the IRA Provisionals'', former IRA member Maria McGuire described her sentiments following the Donegall Street bombing,I admit at the time I did not connect with the people who were killed or injured in such explosions. I always judged such deaths in terms of the effect they would have on our support - and I felt that this in turn depended on how many people accepted our explanation."Revealed: Maria Gatland's life with the IRA in her own words". ''This is Croydon Today''. Dave Burke. 5 December 2008

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Donegall Street bombing 1972 in Northern Ireland Explosions in 1972 The Troubles in Belfast Provisional Irish Republican Army actions Car and truck bombings in Northern Ireland Royal Ulster Constabulary March 1972 events in the United Kingdom 1972 crimes in the United Kingdom Building bombings in Northern Ireland