Donald Henderson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Donald Ainslie Henderson (September 7, 1928 – August 19, 2016) was an American medical doctor, educator, and

Henderson graduated from

Henderson graduated from

epidemiologist

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population.

It is a cornerstone of public health, and shapes policy decisions and evid ...

who directed a 10-year international effort (1967–1977) that eradicated smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

throughout the world and launched international childhood vaccination programs. From 1977 to 1990, he was Dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. Later, he played a leading role in instigating national programs for public health preparedness and response following biological attacks and national disasters. At the time of his death, he was Professor and Dean Emeritus of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Professor of Medicine and Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh, as well as Distinguished Scholar at the UPMC Center for Health Security.

Early life and education

Henderson was born in Lakewood, Ohio on September 7, 1928, of Scots-Canadian immigrant parents. His father, David Henderson, was an engineer; his mother, Eleanor McMillan, was a nurse. His interest in medicine was inspired by a Canadian uncle, William McMillan, who was a general practitioner and senior member of the Canadian House of Commons.Henderson, D.A. ''Smallpox: The Death of a Disease''. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2009. p. 21. Henderson graduated from

Henderson graduated from Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a private liberal arts college and conservatory of music in Oberlin, Ohio. It is the oldest coeducational liberal arts college in the United States and the second oldest continuously operating coeducational institute of highe ...

in 1950 and received his MD from the University of Rochester School of Medicine

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the ...

in 1954. He was a resident physician in medicine at the Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital in Cooperstown, New York

Cooperstown is a village in and county seat of Otsego County, New York, United States. Most of the village lies within the town of Otsego, but some of the eastern part is in the town of Middlefield. Located at the foot of Otsego Lake in the ...

, and, later, a Public Health Service Officer in the Epidemic Intelligence Service of the Communicable Disease Center

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency, under the Department of Health and Human Services, and is headquartered in Atlanta, Georg ...

(now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—CDC). He earned an MPH degree in 1960 from the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health (now the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is the public health graduate school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. As the second independent, degree-granting institution for research in epi ...

).

Research and career

Eradication of smallpox

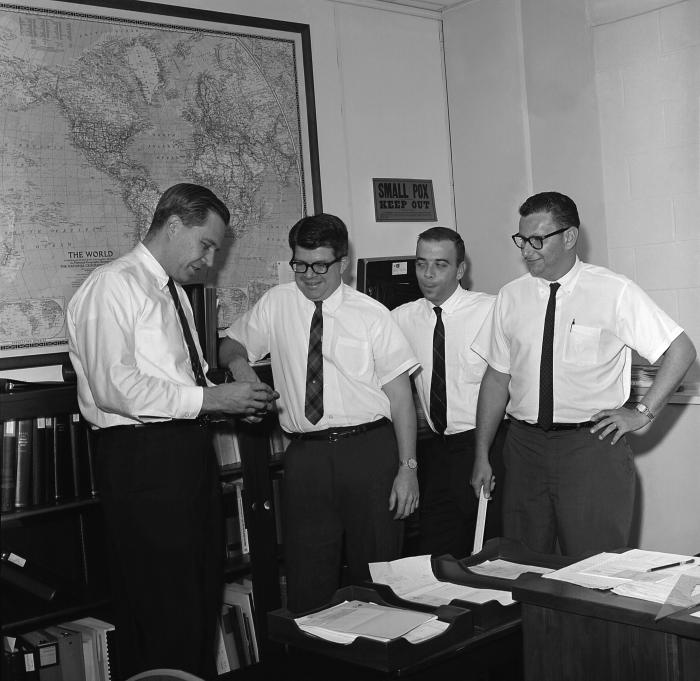

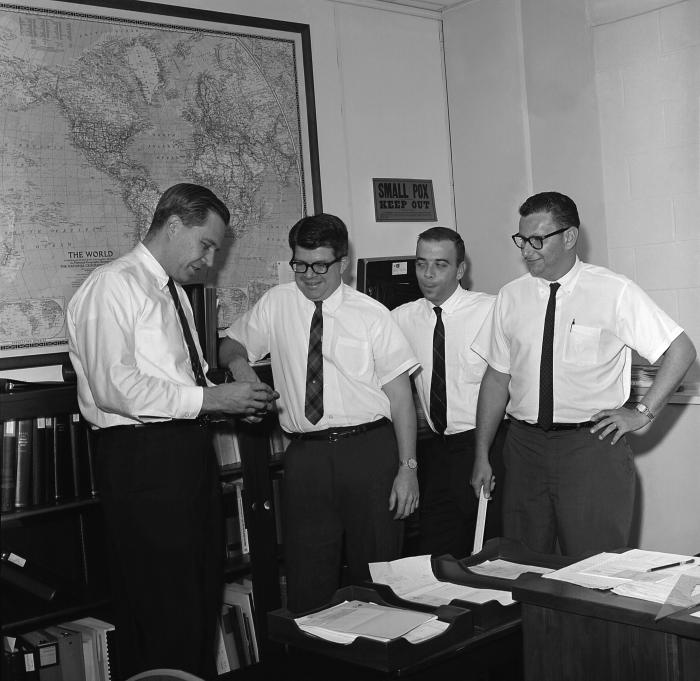

Henderson served as Chief of the CDC virus diseaser surveillance programs from 1960 to 1965, working closely with epidemiologistAlexander Langmuir

Alexander Duncan Langmuir (12 September 1910 – 22 November 1993) was an American epidemiologist. He is renowned for creating the Epidemic Intelligence Service.

Biography

Alexander D. Langmuir was born in Santa Monica, California. He received h ...

. During this period, he and his unit developed a proposal for a United States Agency for International Development

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an independent agency of the U.S. federal government that is primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid and development assistance. With a budget of over $27 b ...

(USAID) program to eliminate smallpox and control measles during a 5-year period in 18 contiguous countries in western and central Africa. This project was funded by USAID, with field operations beginning in 1967.

The USAID initiative provided an important impetus to a World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level o ...

(WHO) program to eradicate smallpox throughout the world within a 10-year period. In 1966, Henderson moved to Geneva to become director of the campaign. At that time, smallpox was occurring widely throughout Brazil and in 30 countries in Africa and South Asia. More than 10 million cases and 2 million deaths were occurring annually. Vaccination brought some control, but the key strategy was "surveillance-containment". This technique entailed rapid reporting of cases from all health units and prompt vaccination of household members and close contacts of confirmed cases. WHO staff and advisors from some 73 countries worked closely with national staff. The last case occurred in Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constitut ...

on October 26, 1977, only 10 years after the program began. Three years later, the World Health Assembly recommended that smallpox vaccination could cease. Smallpox is the first human disease ever to be eradicated. This success gave impetus to WHO's global Expanded Program on Immunization, which targeted other vaccine-preventable diseases, including poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 70% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe sym ...

, measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, tetanus

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a bacterial infection caused by ''Clostridium tetani'', and is characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. Each spasm usually ...

, diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

, and whooping cough

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a highly contagious bacterial disease. Initial symptoms are usually similar to those of the common cold with a runny nose, fever, and mild cough, but these are followed by two or t ...

. Now targeted for eradication are poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 70% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe sym ...

and Guinea Worm

''Dracunculus medinensis'', or Guinea worm, is a nematode that causes dracunculiasis, also known as guinea worm disease. The disease is caused by the female which, at up to in length, is among the longest nematodes infecting humans. In contr ...

disease; after 25 years, this objective is close to being achieved.

Later work

From 1977 through August 1990, Henderson was Dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. After being awarded the 1986 National Medal of Science byRonald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

for his work leading the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level o ...

(WHO) smallpox eradication campaign, Henderson launched a public struggle to reverse the Reagan administration’s decision to default on WHO payments. In 1991, he was appointed associate director for life sciences, Office of Science and Technology Policy, Executive Office of the President (1991–93) and, later, deputy assistant secretary and senior science advisor in the Department of Health and Human Services

The United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is a cabinet-level executive branch department of the U.S. federal government created to protect the health of all Americans and providing essential human services. Its motto is ...

(HHS). In 1998, he became the founding director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense Strategies, now the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security

The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (abbreviated CHS) is an independent, nonprofit organization of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The center works to protect people's health from epidemics and pandemics and ensures ...

.

Following the September 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center, HHS Secretary Tommy G. Thompson asked Henderson to assume responsibility for the Office of Public Health Preparedness (later the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response). For this purpose, $3 billion was appropriated by Congress.

In 2006, Henderson published an academic paper critical of social distancing

In public health, social distancing, also called physical distancing, (NB. Regula Venske is president of the PEN Centre Germany.) is a set of non-pharmaceutical interventions or measures intended to prevent the spread of a contagious dis ...

as a pandemic

A pandemic () is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. A widespread endemic disease with a stable number of in ...

measure, saying it would "result in significant disruption of the social functioning of communities and result in possibly serious economic problems".

At the time of his death, he served as the Editor Emeritus of the academic journal ''Health Security'' (formerly ''Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science'').

Honors and awards

* 1975 – George McDonald Medal,London School of Tropical Medicine

The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a public research university in Bloomsbury, central London, and a member institution of the University of London that specialises in public health and tropical medicine.

The inst ...

* 1978 – Public Welfare Medal, National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

* 1985 – Albert Schweitzer International Prize for Medicine

* 1986 – National Medal of Science in Biology

* 1988 – The Japan Prize, shared with Isao Arita and Frank Fenner

Frank John Fenner (21 December 1914 – 22 November 2010) was an Australian scientist with a distinguished career in the field of virology

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focus ...

* 1990 – Health for All Medal, World Health Organization

* 1994 – Albert B. Sabin Gold Medal, Sabin Foundation

* 1995 – John Stearns Medal, New York Academy of Medicine

* 1996 – Edward Jenner Medal, Royal Society of Medicine

* 2001 – Clan Henderson Society, Chiefs Order

* 2002 – Presidential Medal of Freedom

* 2013 – Order of Brilliant Star, with Grand Cordon, Republic of China

* 2014 – Prince Mahidol Award

The Prince Mahidol Award ( th, รางวัลสมเด็จเจ้าฟ้ามหิดล) is an annual award for outstanding achievements in medicine and public health worldwide. The award is given by the Prince Mahidol Award Found ...

, Thailand

* 2015 – Charles Merieux Award, National Foundation for Infectious Diseases

Seventeen universities conferred honorary degrees on Henderson.

Selected publications

* Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Jezek Z, Ladnyi. (1988) ''Smallpox and Its Eradication'' (), Geneva, World Health Organization. The definitive archival history of smallpox. * Henderson DA. (2009) ''Smallpox, the Death of a Disease'' () New York: Prometheus Books * Henderson DA (1993) Surveillance systems and intergovernmental cooperation. In: Morse SS, ed. ''Emerging Viruses''. New York: Oxford University Press: 283–289. * Henderson DA, Borio LL (2005) Bioterrorism: an overview. In ''Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases'' (Eds. Mandell MD, Bennett JE, Dolin R) Phil, Churchill Livingstone, 3591–3601. * Henderson DA (2010) The global eradication of smallpox: Historical Perspective and Future Prospects in ''The Global Eradication of Smallpox'' (Ed: Bhattacharya S, Messenger S) Orient Black Swan, London. 7–35 * * * * Henderson DA. (1967) Smallpox eradication and measles-control programs in West and Central Africa: Theoretical and practical approaches and problems. ''Industry and Trop Health'' VI, 112–120, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. * * * * * . * * *Personal life

Henderson married Nana Irene Bragg in 1951. The couple had a daughter and two sons. He died at Gilchrist Hospice,Towson, Maryland

Towson () is an unincorporated community and a census-designated place in Baltimore County, Maryland, United States. The population was 55,197 as of the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Baltimore County and the second-most populous unincor ...

, at the age of 87, after fracturing his hip.Archives Reference: The Donald A. Henderson Collection in the Institute of the History of Medicine Library at Johns Hopkins spans his career in smallpox eradication, including newspaper articles, honors, biographical material, lecture notes, speeches, and correspondence as well as medals and other awards.

References

External link

{{DEFAULTSORT:Henderson, Donald Ainslie 1928 births 2016 deaths American public health doctors Donald Ainslie Henderson Oberlin College alumni People from Lakewood, Ohio National Medal of Science laureates University of Pittsburgh faculty Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health alumni Smallpox eradication Vaccinologists American people of Canadian descent American people of Scottish descent Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Members of the National Academy of Medicine