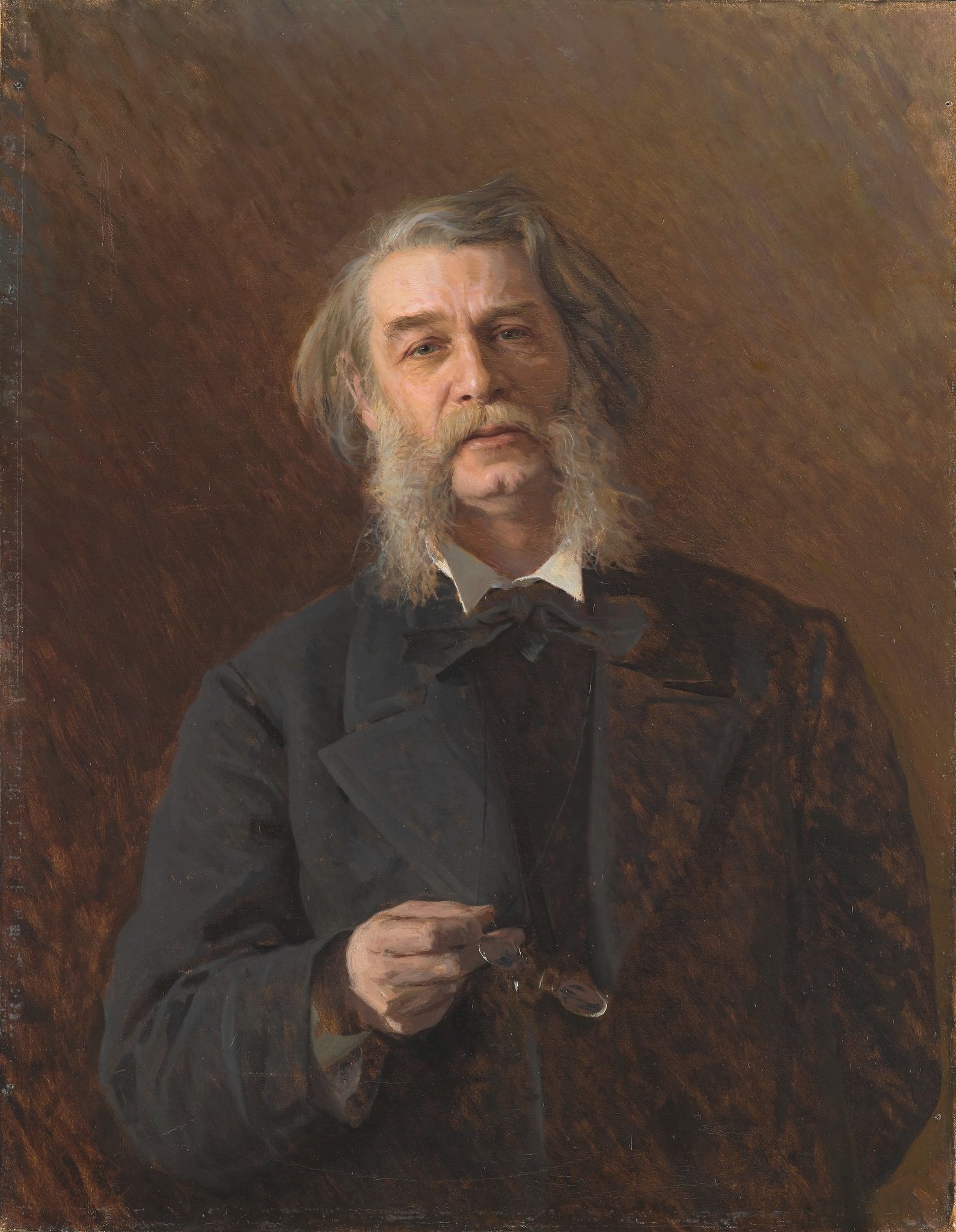

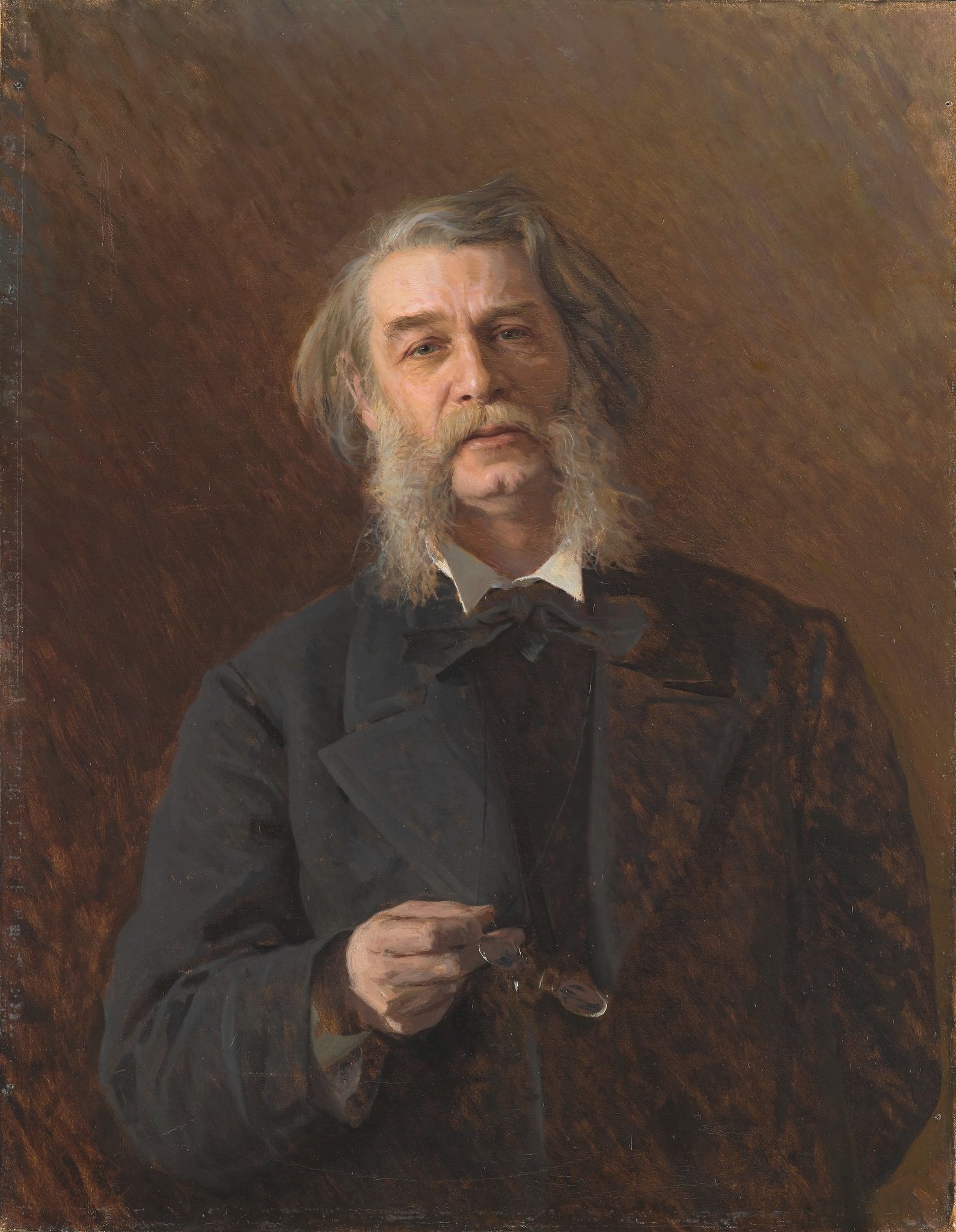

Dmitry Grigorovich on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dmitry Vasilyevich Grigorovich (russian: Дми́трий Васи́льевич Григоро́вич) ( – ) was a Russian writer, best known for his first two novels, '' The Village'' and '' Anton Goremyka'', and lauded as the first author to have realistically portrayed the life of the Russian rural community and openly condemn the system of

Dmitry Grigorovich was born in

Dmitry Grigorovich was born in

While working at the Academy of Arts' chancellery, Grigorovich joined the close circle of actors, writers and scriptwriters. Soon he started writing himself, and made several translations of French

While working at the Academy of Arts' chancellery, Grigorovich joined the close circle of actors, writers and scriptwriters. Soon he started writing himself, and made several translations of French  Grigorovich's second short novel '' Anton Goremyka'' (Luckless Anton, 1847), promptly published this time by ''

Grigorovich's second short novel '' Anton Goremyka'' (Luckless Anton, 1847), promptly published this time by ''

In 1862 Grigorovich travelled to

In 1862 Grigorovich travelled to

Dmitry Grigorovich is generally regarded as the first writer to have shown the real life of the Russian rural community in its full detail, following the tradition of the

Dmitry Grigorovich is generally regarded as the first writer to have shown the real life of the Russian rural community in its full detail, following the tradition of the

from Google Books

*''The Peasant'', (short novel), from ''Russian Sketches'', Smith Elder & Co, 1913

from Archive.org

* ''The Fishermen'', (novel-1853), Stanley Paul and Co, 1916

from Archive.org

serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

.

Biography

Dmitry Grigorovich was born in

Dmitry Grigorovich was born in Simbirsk

Ulyanovsk, known until 1924 as Simbirsk, is a city and the administrative center of Ulyanovsk Oblast, Russia, located on the Volga River east of Moscow. Population:

The city, founded as Simbirsk (), was the birthplace of Vladimir Lenin ( ...

to a family of the landed gentry. His Russian father was a retired hussar

A hussar ( , ; hu, huszár, pl, husarz, sh, husar / ) was a member of a class of light cavalry, originating in Central Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries. The title and distinctive dress of these horsemen were subsequently widely ...

officer, his French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

mother, Cydonia de Varmont, was a daughter of a royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gov ...

who perished on guillotine

A guillotine is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at t ...

in the times of the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First French Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public Capital punishment, executions took pl ...

. Having lost his father early in his life, Dmitry was brought up by his mother and grandmother, the two women who hardly spoke anything but French. Up until the age of eight the boy had serious difficulties with his Russian.Meshcheryakov, V. The Introduction to the Selected Works by D.V.Grigorovich. Moscow. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers, 1976. Pp. 527-530 "I was taking my lessons of Russian from servants, local peasants but mostly from my father's old kammerdiener Nikolai... For hours on end was he waiting for the moment I'd be let out to play and then he'd grab me by the hand and walk me through fields and groves, telling fairytales and all kinds of adventure stories. Cast in coldness of my lonely childhood, I was thawing only when having these walks with Nikolai," Grigorovich remembered later.

In 1832 Grigorovich entered a German gymnasium, then was moved to the French Monighetty boarding school in Moscow. In 1835 he enrolled at the Nikolayevsky Engineering Institute, where he made friends with his fellow student Fyodor Dostoyevsky who's got him interested in literature.''Handbook of Russian Literature'', ed. Victor Terras, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990).''Reminiscences of Grigorovich'', from ''Letters of F.M. Dostoyevsky to His Family and Friends'' (New York: Macmillan). In 1840 Grigorovich quit the institute after the severe punishment he'd received for failing to formally greet the Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich, as the latter was passing by. He joined the Imperial Academy of Arts

The Russian Academy of Arts, informally known as the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, was an art academy in Saint Petersburg, founded in 1757 by the founder of the Imperial Moscow University Ivan Shuvalov under the name ''Academy of the Thr ...

where Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

was his close friend.Lotman, L.M. The Introduction to the Selected Works of D.V.Grigorovich. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers. 1955. Pp. 3-19 One of his first literary acquaintances was Nikolay Nekrasov

Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov ( rus, Никола́й Алексе́евич Некра́сов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɐlʲɪkˈsʲejɪvʲɪtɕ nʲɪˈkrasəf, a=Ru-Nikolay_Alexeyevich_Nekrasov.ogg, – ) was a Russian poet, writer, critic and publi ...

whom he met while studying at the Academy studios.

Career

While working at the Academy of Arts' chancellery, Grigorovich joined the close circle of actors, writers and scriptwriters. Soon he started writing himself, and made several translations of French

While working at the Academy of Arts' chancellery, Grigorovich joined the close circle of actors, writers and scriptwriters. Soon he started writing himself, and made several translations of French vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

s (''The Inheritance'', ''Champaigne and Opium'', both 1843) into Russian. Nekrasov noticed his first published original short stories, "Theatre Carriage" (1844) and "A Doggie" (1845), both bearing strong Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; uk, link=no, Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, translit=Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; (russian: Яновский; uk, Яновський, translit=Yanovskyi) ( – ) was a Russian novelist, ...

influence, and invited him to take part in the almanac '' The Physiology of Saint Petersburg'' he was working upon at the time. Grigorovich's contribution to it, a detailed study of the life of the travelling musicians of the city called ''St. Petersburg Organ Grinders'' (1845), was praised by the influential critic Vissarion Belinsky

Vissarion Grigoryevich Belinsky ( rus, Виссарион Григорьевич БелинскийIn Belinsky's day, his name was written ., Vissarión Grigórʹjevič Belínskij, vʲɪsərʲɪˈon ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲjɪvʲɪdʑ bʲɪˈlʲinskʲ ...

, to whom Nekrasov soon introduced him personally.

In the mid-1840s, Grigorovich, now a journalist, specializing in sketches for ''Literaturnaya Gazeta

''Literaturnaya Gazeta'' (russian: «Литературная Газета», ''Literary Gazette'') is a weekly cultural and political newspaper published in Russia and the Soviet Union. It was published for two periods in the 19th century, and ...

'' and theatre feuilleton

A ''feuilleton'' (; a diminutive of french: feuillet, the leaf of a book) was originally a kind of supplement attached to the political portion of French newspapers, consisting chiefly of non-political news and gossip, literature and art critici ...

s for '' Severnaya Ptchela'', renewed his friendship with Dostoyevsky who in 1846 read to him his first novel ''Poor Folk

''Poor Folk'' (russian: Бедные люди, ''Bednye lyudi''), sometimes translated as ''Poor People'', is the first novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky, written over the span of nine months between 1844 and 1845. Dostoevsky was in financial difficul ...

''. Greatly impressed, Grigorovich took the manuscript to Nekrasov, who promptly published it.

Also in 1846, Andrey Krayevsky

Andrey Alexandrovich Krayevsky (russian: Андре́й Алекса́ндрович Крае́вский; February 17 .S. 5 1810 – August 20 .S. 8 1889) was a Russian publisher and journalist, best known for his work as an editor-in-chief of ...

's ''Otechestvennye Zapiski

''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' ( rus, Отечественные записки, p=ɐˈtʲetɕɪstvʲɪnːɨjɪ zɐˈpʲiskʲɪ, variously translated as "Annals of the Fatherland", "Patriotic Notes", "Notes of the Fatherland", etc.) was a Russian lite ...

'' (Nekrasov, who'd received the manuscript first, somehow gave it a miss and then forgot all about it) published Grigorovich's short novel '' The Village''. Influenced by Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

's ''Oliver Twist

''Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress'', Charles Dickens's second novel, was published as a serial from 1837 to 1839, and as a three-volume book in 1838. Born in a workhouse, the orphan Oliver Twist is bound into apprenticeship with ...

'' but based on a real life story of a peasant woman (from the village which belonged to his mother) who'd been forcefully married and then beaten by her husband to death, the novel became one of the first in Russian literature to strongly condemn the system of serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

and "the first attempt in the history of our literature to get closer to real people's life," according to Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (; rus, links=no, Ива́н Серге́евич Турге́невIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; 9 November 1818 – 3 September 1883 (Old Style dat ...

.

Grigorovich's second short novel '' Anton Goremyka'' (Luckless Anton, 1847), promptly published this time by ''

Grigorovich's second short novel '' Anton Goremyka'' (Luckless Anton, 1847), promptly published this time by ''Sovremennik

''Sovremennik'' ( rus, «Современник», p=səvrʲɪˈmʲenʲːɪk, a=Ru-современник.ogg, "The Contemporary") was a Russian literary, social and political magazine, published in Saint Petersburg in 1836–1866. It came out ...

'', made the author famous. "Not a single Russian novel has yet brought upon me such an impression of horrible, damning doom," Belinsky confided in a letter to critic Vasily Botkin. The realistic treatment of the life of Russian peasants in these two novels was praised by fellow writers Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin

Mikhail Yevgrafovich Saltykov-Shchedrin ( rus, Михаи́л Евгра́фович Салтыко́в-Щедри́н, p=mʲɪxɐˈil jɪvˈɡrafəvʲɪtɕ səltɨˈkof ɕːɪˈdrʲin; – ), born Mikhail Yevgrafovich Saltykov and known during ...

and Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

among others, and had a considerable impact on the writing of that period. "There'd be not a single educated man in those times and in the years to come who'd read ''Luckless Anton'' without tears of passion and hatred, damning horrors of serfdom," wrote Pyotr Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and acti ...

. ''Anton Goremyka'' was included into the list of the "most dangerous publications of the year," alongside articles by Belinsky and Alexander Hertzen

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Ге́рцен, translit=Alexándr Ivánovich Gértsen; ) was a Russian writer and thinker known as the "father of Russian socialism" and one of the main fathers of agra ...

, by the Special Literature and Publishing Committee.

In the late 1840 - early 1850s Grigorovich's fame started to wane. Partly, it got eclipsed by the publication of Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (; rus, links=no, Ива́н Серге́евич Турге́невIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; 9 November 1818 – 3 September 1883 (Old Style dat ...

's ''A Sportsman's Sketches

''A Sportsman's Sketches'' (russian: Записки охотника, Zapiski ohotnika; also known as ''A Sportman's Notebook'', ''The Hunting Sketches'' and ''Sketches from a Hunter's Album'') is an 1852 cycle of short stories by Ivan Turgenev. ...

'', but also, his own works of the so-called 'seven years of reaction', 1848-1855 period were not quite up to the standard set by his first two masterpieces. Highlighting the brighter sides of the life of the Russian rural community of the time, they were closer to liberal doctrines then to the radical views of Nikolai Chernyshevsky

Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky ( – ) was a Russian literary and social critic, journalist, novelist, democrat, and socialist philosopher, often identified as a utopian socialist and leading theoretician of Russian nihilism. He was ...

who was gaining more and more influence in ''Sovremennik''. Several satirical short stories of this period ("Adventures of Nakatov", "Short Term Wealth", "Svistulkin") could hardly be called in any way subversive. The short novel ''Four Seasons'' (1849) has been described as "a kind of simplistic Russian low-life idyll" by the author himself. "Things are as bad as they've never been. What with censorship being now so fierce, whatever I'd choose to publish might get me into trouble," Grigorovich complained in an 1850 letter.

Grigorovich's epic, sprawling novel ''Cart-Tracks'' (Prosyolochnye Dorogi, 1852) with its gallery of social parasites came under criticism for being overblown and derivative, Gogol's ''Dead Souls

''Dead Souls'' (russian: «Мёртвые души», ''Mjórtvyje dúshi'') is a novel by Nikolai Gogol, first published in 1842, and widely regarded as an exemplar of 19th-century Russian literature. The novel chronicles the travels and adve ...

'' considered the obvious point of reference. Better received was his '' The Fishermen'' (Rybaki, 1853) novel, one of the earliest works of Russian literature pointing at the emergence of kulak

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ove ...

(rich, exploitative peasant) in the Russian rural environment. Hertzen in his detailed review praised the way the author managed to get rid of his early influences but deplored what he thought was the lack of one strong, positive character. ''The Fishermen'', according to Hertzen, "brought us first signs that Russian society started to recognize an important social force in its ommonpeople." The emerging proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

, though, drew little sympathy from the author. "The decline of morality in the Russian village is often caused by ices ofthe factory way of life," he opined.

Another novel dealing with the conflict between Russian serfs and their owners, ''The Settlers'' (Pereselentsy, 1855), was reviewed positively by Nikolai Chernyshevsky

Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky ( – ) was a Russian literary and social critic, journalist, novelist, democrat, and socialist philosopher, often identified as a utopian socialist and leading theoretician of Russian nihilism. He was ...

, who still refused to see (what he termed) 'philanthropy

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

' as providing the means for mending profound social schisms. Critics of all camps, though, praised Grigorovich's pictures of nature, the result of his early fascination with fine arts; numerous lyrical extracts from his books have made their way into school textbooks. Both ''The Fishermen'' and ''The Settlers'' strengthened Grigorovich's reputation and Nekrasov has got him to sign a special contract making sure he (alongside Ivan Turgenev, Alexander Ostrovsky

Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Остро́вский; ) was a Russian playwright, generally considered the greatest representative of the Russian realistic period. The author of 47 original ...

and Leo Tolstoy) would from then on write for ''Sovremennik'' exclusively.

In the mid-1850s, as the rift between Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

radicals and liberals in the Russian literature was becoming more and more pronounced, Grigorovich made a strong neutral stand and attempted to make Nekrasov see that his way of "quarrelling with other journals" has been causing harm to both himself and ''Sovremennik'', as Grigorovich saw it. In keeping with this spirit of peace and compromise was his next small novel ''Ploughman'' (Pakhar, 1856), either a paean to the "strength of the Russian folk spirit," or a comment on a man of the land's utter endurance, depending upon a viewpoint. ''School of Hospitality'' (Shkola gostepriimstva, 1855), written under the influence of Alexander Druzhinin (and, allegedly, not without his direct participation), was in effect a swipe at Chernyshevsky, but the latter refused to be provoked and personal relations between the two men never soured, even if their ideological differences now were irreconcilable. Several years later, as Druzhinin and his fellow proponents of the 'arts for arts' sake' doctrine instigated a dispute along the lines of "free-thinking Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

versus overcritical Gogol," Grigorovich backed the Chernyshevsky-led ''Sovremennik'' group, despite being friends with Druzhinin.

''Notes on Modern Ways'' (Otcherki sovremennykh nravov, 1857), published in ''Sovremennik'', satirized Russian bureaucracy, but by this time signs of the forthcoming crisis have already been obvious. "Never before had I such doubts about myself, there are times when I feel totally downtrodden," he confessed in an 1855 letter to Druzhinin.

In 1858, Grigorovich accepted the Russian Navy Ministry's invitation to make a round-Europe voyage on warship Retvizan and later described it in ''The Ship Retvizan'' (1858-1863). Back in Russia, Grigorovich started his own Popular Readings project but this 10-book series failed to make an impact. Grigorovich was planning to comment on the demolition of serfdom in ''Two Generals'' (Dva Generala, 1864), but this novel, recounting the story of two generations of landowners, remained unfinished. In the mid-1860s he stopped writing altogether to concentrate on studying painting and collecting items of fine arts. "Painting has always interested me more than literature," admitted Grigorovich, whom many specialists considered a scholar in this field.

Later life

In 1862 Grigorovich travelled to

In 1862 Grigorovich travelled to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

to study the English fine arts at the 1862 International Exhibition

The International Exhibition of 1862, or Great London Exposition, was a world's fair. It was held from 1 May to 1 November 1862, beside the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society, South Kensington, London, England, on a site that now houses ...

, as well as several other galleries. In 1863 ''Russky Vestnik

The ''Russian Messenger'' or ''Russian Herald'' (russian: Ру́сский ве́стник ''Russkiy Vestnik'', Pre-reform Russian: Русскій Вѣстникъ ''Russkiy Vestnik'') has been the title of three notable magazines published in ...

'' published an account of his studies, ''Paintings by English Artists at the 1862 London Exhibitions'', by far the most comprehensive analysis of British painting to have appeared in the Russian press. He especially liked the works of William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt (2 April 1827 – 7 September 1910) was an English painter and one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His paintings were notable for their great attention to detail, vivid colour, and elaborate symbolism ...

.

In 1864 Grigorovich was elected the Secretary of the Russian Society for Encouraging Artists and held this post for twenty years, doing much to improve the art education throughout the country. The Museum of Art History he organized at the Society was credited with being one of the best in Europe of its kind. At the Society's School of Drawing Grigorovich gathered the best teachers from all over Russia, and made sure exhibitions and contests were being held regularly, with winners receiving grants from the Society. Grigorovich was the first to discover and support the soon-to-become famous painters Fyodor Vasilyev

Fyodor Alexandrovich Vasilyev (russian: Фёдор Александрович Васильев, 1850 – 1873) was a Russian Imperial landscape painter who introduced the lyrical landscape style in Russian art.

Biography

Fyodor Vasilyev ...

and Ilya Repin

Ilya Yefimovich Repin (russian: Илья Ефимович Репин, translit=Il'ya Yefimovich Repin, p=ˈrʲepʲɪn); fi, Ilja Jefimovitš Repin ( – 29 September 1930) was a Russian painter, born in what is now Ukraine. He became one of the ...

. His achievements as the head of the Society Grigorovich earned him the status of the Actual State Councilor and a lifetime pension.

In 1883 Grigorovich the writer made an unexpected comeback with the "Gutta-Percha Boy" (Guttaperchevy Maltchik) which was unanimously hailed as the author's 'little masterpiece'. The story of a teenage circus virtuoso's death made its way into the Russian classic children's reading lists and was adapted for the big screen twice, in 1915 and 1957. Also in 1883 Grigorovich translated Prosper Mérimée

Prosper Mérimée (; 28 September 1803 – 23 September 1870) was a French writer in the movement of Romanticism, and one of the pioneers of the novella, a short novel or long short story. He was also a noted archaeologist and historian, and a ...

's "Le Vase Etrusque" into Russian, his version of it regarded in retrospect as unsurpassed. In 1885 his satirical novel ''Acrobats of Charity'' (Akrobaty blagotvoritelnosti) came out and caused much debate. Its title became a popular token phrase (used, notably, by Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

in one of his 1901 works) and the play ''The Suede People'' based on this short story was produced at the Moscow Art Theatre

The Moscow Art Theatre (or MAT; russian: Московский Художественный академический театр (МХАТ), ''Moskovskiy Hudojestvenny Akademicheskiy Teatr'' (МHАТ)) was a theatre company in Moscow. It was f ...

by Konstantin Stanislavsky.

In 1886, Grigorovich famously encouraged young Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; 29 January 1860 Old Style date 17 January. – 15 July 1904 Old Style date 2 July.) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer who is considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career ...

, telling him in a letter that he had a gift and should approach literature with more seriousness. "Your letter... struck me like a flash of lightning. I almost burst into tears, I was overwhelmed, and now I feel it left a deep mark on my soul," Chekhov replied. In his ''Literary Memoirs'' (1892–1993), Grigorovich created a vast panorama of the Russian 1840s–1850s literary scene and (while carefully avoiding political issues) left vivid portraits of the people he knew well, like Ivan Turgenev, Vasily Botkin and Leo Tolstoy.

Dmitry Vasilyevich Grigorovich died in Saint Petersburg on January 3, 1900. He is interred in Volkovo Cemetery

The Volkovo Cemetery (also Volkovskoe) (russian: Во́лковское кла́дбище or Во́лково кла́дбище) is one of the largest and oldest non- Orthodox cemeteries in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Until the early 20th century i ...

.

Legacy

Dmitry Grigorovich is generally regarded as the first writer to have shown the real life of the Russian rural community in its full detail, following the tradition of the

Dmitry Grigorovich is generally regarded as the first writer to have shown the real life of the Russian rural community in its full detail, following the tradition of the Natural School Natural School (russian: Натуральная школа, Naturalnaya Shkola) is a term applied to the literary movement which arose under the influence of Nikolai Gogol in the 1840s in Russia, and included such diverse authors as Nikolai Nekrasov ...

movement to which he in the 1840s belonged. His first two short novels, '' The Village'' and '' Anton Goremyka'', are seen as precursors for several important works by Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (; rus, links=no, Ива́н Серге́евич Турге́невIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; 9 November 1818 – 3 September 1883 (Old Style dat ...

, Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

and Nikolai Leskov

Nikolai Semyonovich Leskov (russian: Никола́й Семёнович Леско́в; – ) was a Russian novelist, short-story writer, playwright, and journalist, who also wrote under the pseudonym M. Stebnitsky. Praised for his unique w ...

. As harsh critic of serfdom, he's been linked to the line of Radishchev, Griboyedov Griboyedov may refer to:

* Alexander Griboyedov (1795-1829), Russian playwright and diplomat

* Griboyedov Canal

The Griboyedov Canal or Kanal Griboyedova () is a canal in Saint Petersburg, constructed in 1739 along the existing ''Krivusha'' r ...

and Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

.

Numerous writers, critics and political activists, Alexander Hertzen

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Ге́рцен, translit=Alexándr Ivánovich Gértsen; ) was a Russian writer and thinker known as the "father of Russian socialism" and one of the main fathers of agra ...

among them, noted the impact that his second novel ''Anton Goremyka'' have had upon the development of social consciousness in Russia. It greatly influenced the new, politically-minded generation of Russian intelligentsia of the mid-19th century and in many ways helped launch the early socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

movement in the country. Saltykov-Shchedrin called the first two books by Grigorovich "a springtime rain which invigorated Russian literary soil." Both made the Russian educated society aware for the first time of the plight of muzhik

Agriculture in the Russian Empire throughout the 19th-20th centuries Russia represented a major world force, yet it lagged technologically behind other developed countries. Imperial Russia (officially founded in 1721 and abolished in 1917) was am ...

, as a human being, not an abstraction, according to the famous satirist. Leo Tolstoy praised Grigorovich for having portrayed Russian peasants "with love, respect and something close to trepidation," writing of enormous impact his "vast, epic tapestries like ''Anton Goremyka'' have made."L.N.Tolstoy Remembered by Contemporaries. Moscow. Goslitizdat. 1930. Vol.II, Pp 120, 128

According to Semyon Vengerov, Grigorovich's first two novels marked the peak of his whole career. "All of his later books were written with the same sympathy for the common man, but failed to excite," this literary historian

The history of literature is the historical development of writings in prose or poetry that attempt to provide entertainment, enlightenment (concept), enlightenment, or Education, instruction to the reader/listener/observer, as well as the devel ...

argued. Some critics belonging to the Russian left (Vengerov included) made much of the fact that Grigorovich (as well as Turgenev) allegedly 'hated' Chernyshevsky; others considered his works deficient, for being not radical enough. Critics from all camps, though, admired Grigorovich for his fine, simple, yet colourful language and praised him as a master of 'natural landscape'. This gift, developed apparently as a result of his love for fine arts and painting, was quite extraordinary for someone who'd been brought up by two French women and up until the age of eight spoke hardly any Russian at all.

English translations

*''The Cruel City'', (novel-1855/56), Cassell Publishing Company, 1891from Google Books

*''The Peasant'', (short novel), from ''Russian Sketches'', Smith Elder & Co, 1913

from Archive.org

* ''The Fishermen'', (novel-1853), Stanley Paul and Co, 1916

from Archive.org

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Grigorovich, Dmitry Novelists from the Russian Empire Male writers from the Russian Empire 1822 births 1900 deaths Military Engineering-Technical University alumni Artists from the Russian Empire Art critics from the Russian Empire Russian travel writers People from Ulyanovsk 19th-century journalists Russian male journalists 19th-century novelists from the Russian Empire Male novelists 19th-century male writers from the Russian Empire